Post-Polymerization Modification of Ring Opening Metathesis Polymerization (ROMP)-Derived Materials Using Wittig Reactions

Abstract

:1. Introduction

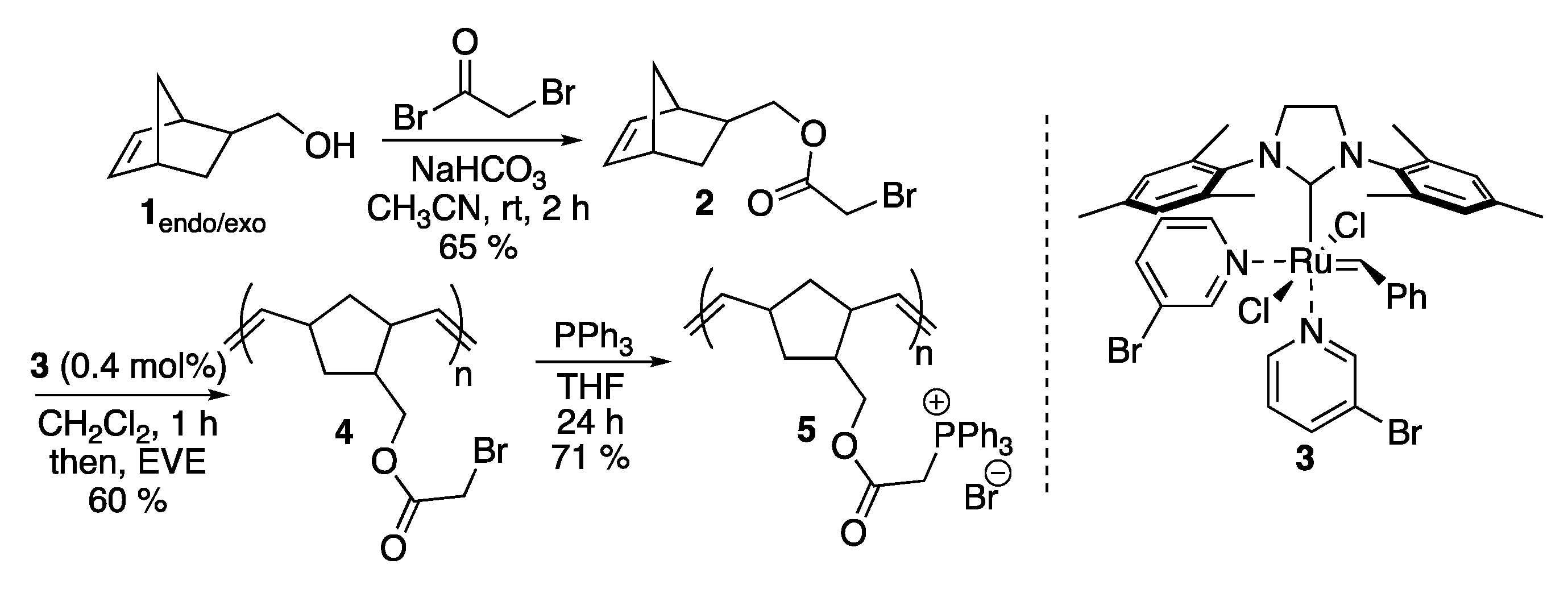

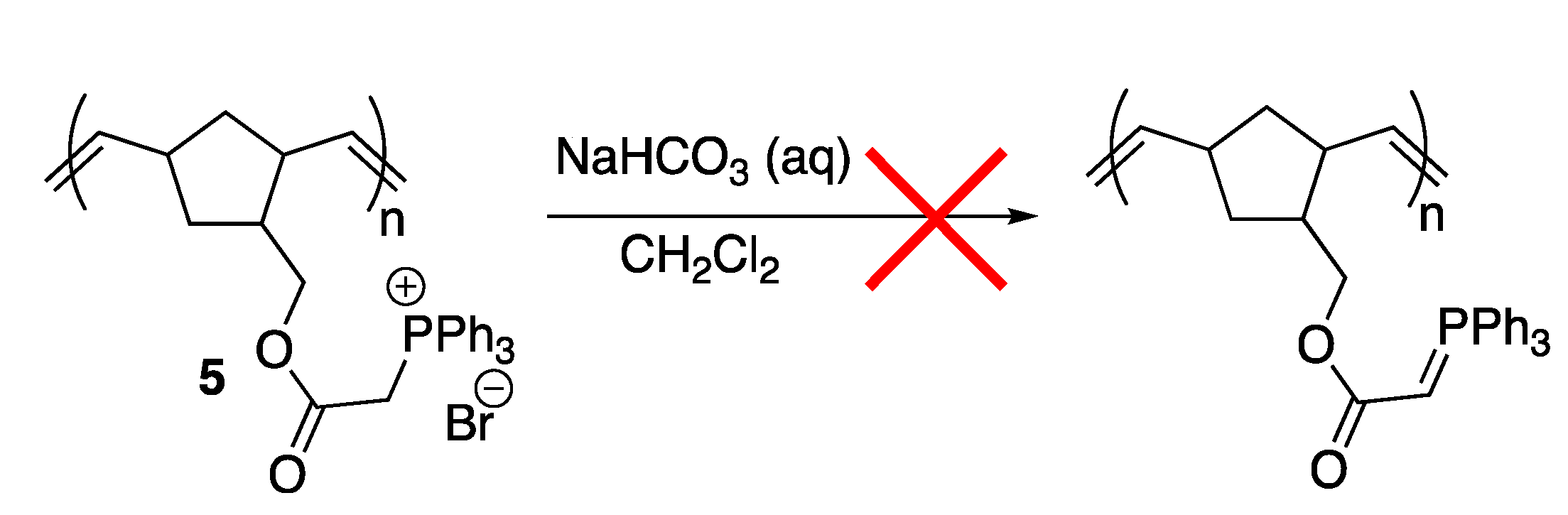

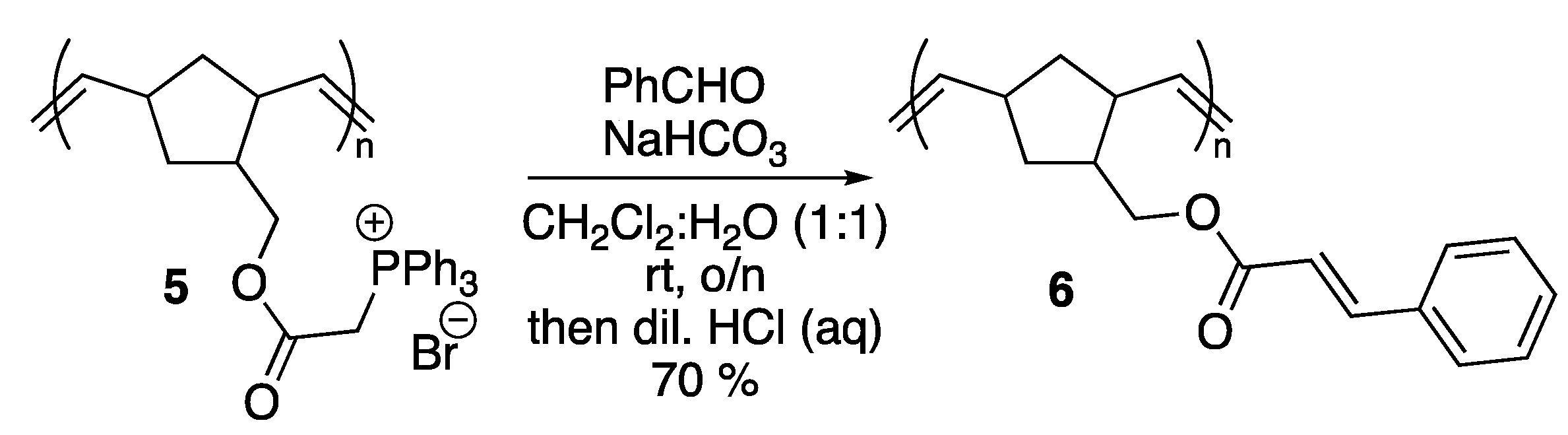

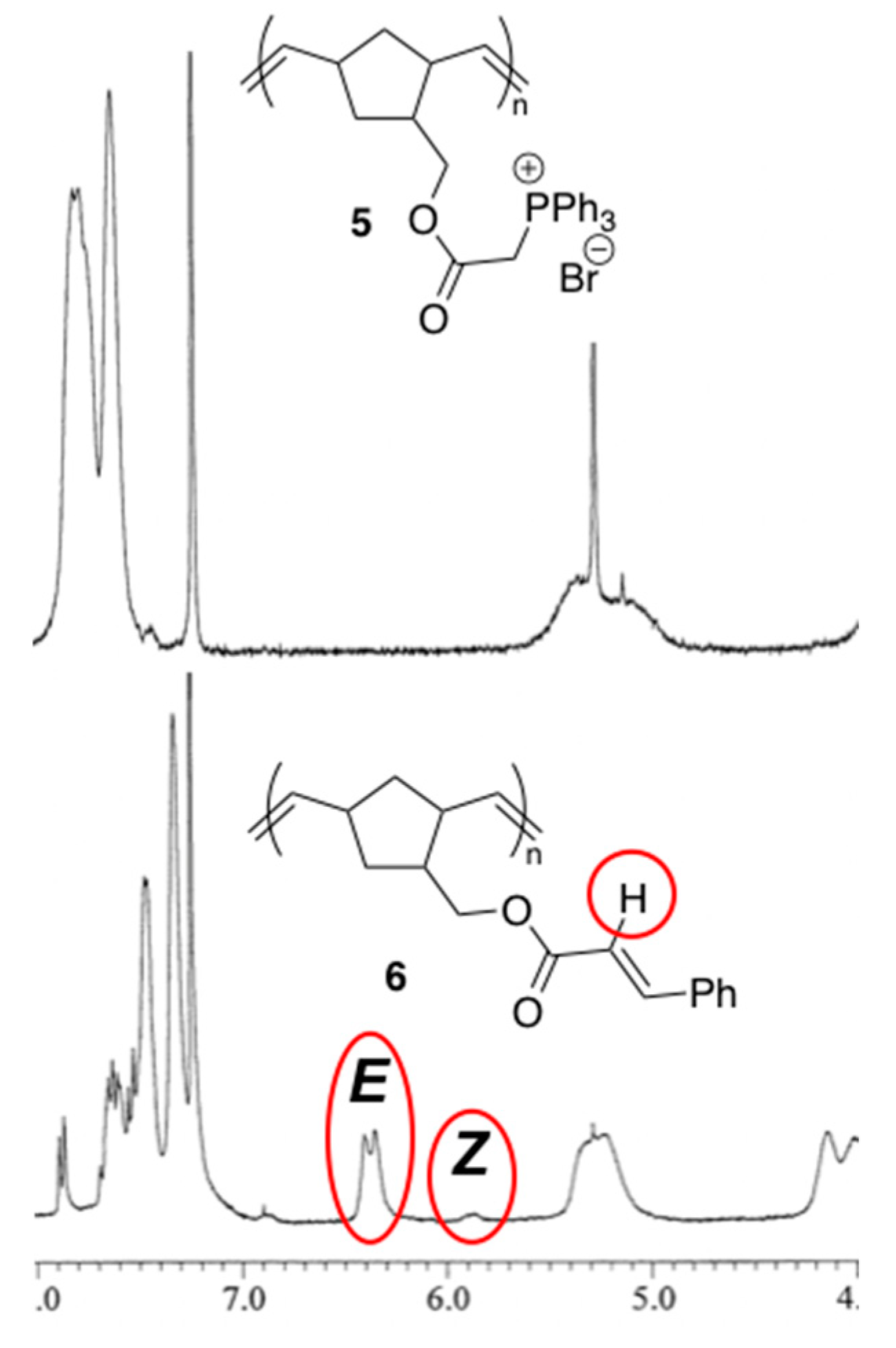

2. Results and Discussion

3. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gauthier, M.A.; Gibson, M.I.; Klok, H.-A. Synthesis of functional polymers by post-polymerization modification. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Günay, K.A.; Theato, P.; Klok, H.-A. Standing on the shoulders of Hermann Staudinger: Post-polymerization modification from past to present. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2013, 51, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Bielawski, C.W. Post-polymerization modification of poly(vinyl ether)s: A Ru-catalyzed oxidative synthesis of poly(vinyl ester)s and poly(propenyl ester)s. Polym. Chem. 2016, 7, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coady, D.J.; Bielawski, C.W. N-Heterocyclic carbenes: Versatile reagents for postpolymerization modification. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 8895–8897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Bielawski, C.W. Synthesis of degradable poly[(ethylene glycol)-co-(glycolic acid)] via the post-polymerization oxyfunctionalization of poly(ethylene glycol). Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2016, 37, 1587–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, T.J.; Comerford, J.W.; Pellis, A.; Robert, T. Post-polymerization modification of bio-based polymers: Maximizing the high functionality of polymers derived from biomass. Polym. Int. 2018, 67, 775–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, J.B.; Na, C.G.; Johnson, R.R.; Daniel, W.F.M.; Alexanian, E.J.; Leibfarth, F.A. Chemo- and regioselective functionalization of isotactic polypropylene: A mechanistic and structure–property study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 12815–12823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, S.E.; Wilhelmy, B.E.; Leibfarth, F.A. Organocatalytic C–H fluoroalkylation of commodity polymers. Polym. Chem. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, H.C.; Finn, M.G.; Sharpless, K.B. Click chemistry: Diverse chemical function from a few good reactions. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2001, 40, 2004–2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastas, P.T.; Constable, D.; Jimenez-Gonzalez, C. Green Metrics; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Grubbs, R.B.; Grubbs, R.H. 50th anniversary perspective: Living polymerization—Emphasizing the molecule in macromolecules. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 6979–6997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matyjaszewski, K. Discovery of the RAFT process and its impact on radical polymerization. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 495–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beers, K.L. The first dive into the mechanism and kinetics of ATRP. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 1115–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yuan, L.; He, L.; Wang, Y.; Lang, X.; Yang, F.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, H. Two- and three-component post-polymerization modifications based on Meldrum’s acid. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 3175–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterling, C.P.; Coste, G.; Sanchez, J.E.; Fanucci, G.E.; Sumerlin, B.S. Post-polymerization modification of polymethacrylates enabled by keto–enol tautomerization. Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 2955–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauenburg, D.; Divandari, M.; Neumann, K.; Speigel, C.A.; Hackett, T.; Dzang, Y.-C.; Spencer, N.D.; Bode, J.W. Synthesis of polymers containing potassium acyltrifluoroborates (KATs) and post-polymerization ligation and conjugation. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2020. accepted. [Google Scholar]

- Bielawski, C.W.; Grubbs, R.H. Living ring-opening metathesis polymerization. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2007, 32, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubbs, R.H.; Wenzel, A.G.; O’Leary, D.J.; Khosravi, E. (Eds.) Handbook of Metathesis, 2nd ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nistanaki, S.K.; Nelson, H.M. Dewar heterocycles as versatile monomers for ring-opening metathesis polymerization. ACS Macro Lett. 2020, 9, 731–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishman, J.M.; Zwick, D.B.; Kruger, A.G.; Kiessling, L.L. Chemoselective, postpolymerization modification of bioactive, degradable polymers. Biomacromolecules 2019, 20, 1018–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strong, L.E.; Kiessling, L.L. A General synthetic route to defined, biologically active multivalent arrays. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 6193–6196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredlund, A.; Kothapalli, V.A.; Hobbs, C.E. Phase-selectively soluble polynorbornene as a catalyst support. Polym. Chem. 2017, 8, 516–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, M.; Hanik, N.; Kilbinger, A.F.M. ROMP copolymers for orthogonal click functionalizations. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 6807–6818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Hensbergen, J.A.; Burford, R.P.; Lowe, A.B. ROMP (co)polymers with pendent alkyne side groups: Post-polymerization modification employing thiol–yne and CuAAC coupling chemistries. Polym. Chem. 2014, 5, 5339–5349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.O.; Kim, J.; Choi, T.-L. Controlled ring-opening metathesis polymerization of a monomer containing terminal alkyne and its versatile postpolymerization functionalization via click reaction. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 4525–4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romulus, J.; Henssler, J.T.; Weck, M. Postpolymerization modification of block copolymers. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 5437–5449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T.A.; Page, R.C.; Konkolewicz, D. Polymer conjugation of proteins as a synthetic post-translational modification to impact their stability and activity. Polym. Chem. 2019, 10, 434–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobbs, C.E.; Vasireddy, M. Combining ATRP and ROMP with thio-bromo, copper-catalyzed, and strain-promoted click reactions for brush copolymer synthesis starting from a single initiator/monomer/click partner. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2019, 220, 1800497–1800502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subnaik, S.I.; Hobbs, C.E. Flow-facilitated ring opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP) and post-polymerization modification reactions. Polym. Chem. 2019, 10, 4524–4528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashlin, M.; Hobbs, C.E. Post-polymerization thiol substitutions facilitated by mechanochemistry. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2019, 220, 1900350–1900354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashok Kothapalli, V.; Shetty, M.; De Los Santos, C.; Hobbs, C.E. Thio-bromo “click”, post-polymerization strategy for functionalizing ring opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP)-derived materials. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2016, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubb, J.; Carosio, F.; Vasireddy, M.; Moncho, S.; Brothers, E.N.; Hobbs, C.E. Ring opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP) and thio-bromo “click” chemistry approach toward the preparation of flame-retardant polymers. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2018, 56, 645–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Gutierrez, D.C.; Hoang, N.H.; Kim, D.; Wang, R.; Hobbs, C.; Zhu, L. Efficient codelivery of paclitaxel and curcumin by novel bottlebrush copolymer-based micelles. Mol. Pharm. 2017, 14, 2378–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Deike, S.; Binder, W.H. One-pot synthesis of thermoresponsive amyloidogenic peptide–polymer conjugates via thio–bromo “click” reaction of RAFT polymers. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2018, 39, 1700507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Döhler, D.; Kaiser, J.; Binder, W.H. Supramolecular H-bonded three-arm star polymers by efficient combination of RAFT polymerization and thio-bromo “click” reaction. Polymer 2017, 122, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biewend, M.; Neumann, S.; Michael, P.; Binder, W.H. Synthesis of polymer-linked copper(i) bis(N-heterocyclic carbene) complexes of linear and chain extended architecture. Polym. Chem. 2019, 10, 1078–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, B.M.; Lligadas, G.; Hahn, C.; Percec, V. Synthesis of dendrimers through divergent iterative thio-bromo “click” chemistry. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2009, 47, 3931–3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, B.M.; Lligadas, G.; Hahn, C.; Percec, V. Synthesis of dendritic macromolecules through divergent iterative thio-bromo “click” chemistry and SET-LRP. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2009, 47, 3940–3948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, T.R.; Brendel, J.C.; Perrier, S. Poly(bromoethyl acrylate): A reactive precursor for the synthesis of functional RAFT materials. Macromolecules 2016, 49, 6203–6212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Z.-L.; Sun, L.; Ma, J.; Zeng, Z.; Jiang, H. Synthesis and post-polymerization modification of polynorbornene bearing dibromomaleimide side groups. Polymer 2016, 84, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, W.H.; Kluger, C. Combining ring-opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP) with sharpless-type “click” reactions: An easy method for the preparation of side chain functionalized poly(oxynorbornenes). Macromolecules 2004, 37, 9321–9330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.K.; Weck, M. Modular covalent multifunctionalization of copolymers. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendel, J.C.; Schmidt, M.M.; Hagen, G.; Moos, R.; Thelakkat, M. Controlled synthesis of water-soluble conjugated polyelectrolytes leading to excellent hole transport mobility. Chem. Mater. 2014, 26, 1992–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, K.; Azuma, H.; Watanabe, T.; Ishizone, T.; Hirao, A. Anionic polymerization of 2-haloethyl methacrylates. Polymer 2003, 44, 4157–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Loma, R.; Albéniz, A.C. Poly(ω-bromoalkylnorbornenes-co-norbornene) by ROMP-hydrogenation: A robust support amenable to post-polymerization functionalization. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 70244–70254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Noga, D.E.; Yoon, K.; Wojtowicz, A.M.; Lin, A.S.P.; García, A.J.; Collard, D.M.; Weck, M. Highly porous crosslinkable PLA-PNB block copolymer scaffolds. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2008, 18, 3638–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hreha, R.D.; Haldi, A.; Domercq, B.; Barlow, S.; Kippelen, B.; Marder, S.R. Synthesis of acrylate and norbornene polymers with pendant 2,7-bis(diarylamino)fluorene hole-transport groups. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 7169–7176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, A.B.; Liu, M.; van Hensbergen, J.A.; Burford, R.P. Combining ring-opening metathesis polymerization and thiol-ene coupling chemistries: Facile access to novel functional linear and nonlinear macromolecules. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2014, 35, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, L.; Cheng, P.; Fang, J.; Xu, T.; Chen, D. Reusable gold nanorod/liquid crystalline elastomer (GNR/LCE) composite films with UV-triggered dynamic crosslinks capable of micropatterning and NIR actuation. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 14245–14254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, D.H.A.; Pinto, D.C.G.A.; Silva, A.M.S. Applications of the wittig reaction on the synthesis of natural and natural-analogue heterocyclic compounds. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 2018, 2443–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Abdellatif, M.M.; Nomura, K. Olefin metathesis polymerization: Some recent developments in the precise polymerizations for synthesis of advanced materials (by ROMP, ADMET). Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 619–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, Z.; Toy, P.H. Catalytic Wittig and aza-Wittig reactions. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2016, 12, 2577–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taylor, M.T.; Nelson, J.E.; Suero, M.G.; Gaunt, M.J. A protein functionalization platform based on selective reactions at methionine residues. Nature 2018, 562, 563–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, J.A.; Morgan, J.P.; Trnka, T.M.; Grubbs, R.H. A practical and highly active ruthenium-based catalyst that effects the cross metathesis of acrylonitrile. Angew. Chemie Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 4035–4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uijttewaal, A.P.; Jonkers, F.L.; Van der Gen, A. Reactions of esters with phosphorus ylides. 2. Mechanistic aspects. J. Org. Chem. 1978, 43, 3306–3311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Entry | RCHO | Prd. | E:Z2 | Yield (%) 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

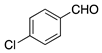

| 1 |  | 6 | 18:1 | 70 |

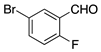

| 2 |  | 7 | 17:1 | 95 |

| 3 |  | 8 | 7:1 | 65 |

| 4 |  | 9 | 12:1 | 83 |

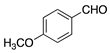

| 5 |  | 10 | 14:1 | 90 |

| 6 |  | 11 | 7:1 | 89 |

| 7 |  | 12 | 5:1 | 65 |

| 8 |  | -- | -- | gel |

| 9 |  | -- | -- | gel |

| 10 |  | -- | -- | gel |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duty, R.; Hobbs, C.E. Post-Polymerization Modification of Ring Opening Metathesis Polymerization (ROMP)-Derived Materials Using Wittig Reactions. Polymers 2020, 12, 1247. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12061247

Duty R, Hobbs CE. Post-Polymerization Modification of Ring Opening Metathesis Polymerization (ROMP)-Derived Materials Using Wittig Reactions. Polymers. 2020; 12(6):1247. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12061247

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuty, Ryan, and Christopher E. Hobbs. 2020. "Post-Polymerization Modification of Ring Opening Metathesis Polymerization (ROMP)-Derived Materials Using Wittig Reactions" Polymers 12, no. 6: 1247. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12061247

APA StyleDuty, R., & Hobbs, C. E. (2020). Post-Polymerization Modification of Ring Opening Metathesis Polymerization (ROMP)-Derived Materials Using Wittig Reactions. Polymers, 12(6), 1247. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12061247