Biodegradation of Different Types of Plastics by Tenebrio molitor Insect

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Insect Rearing

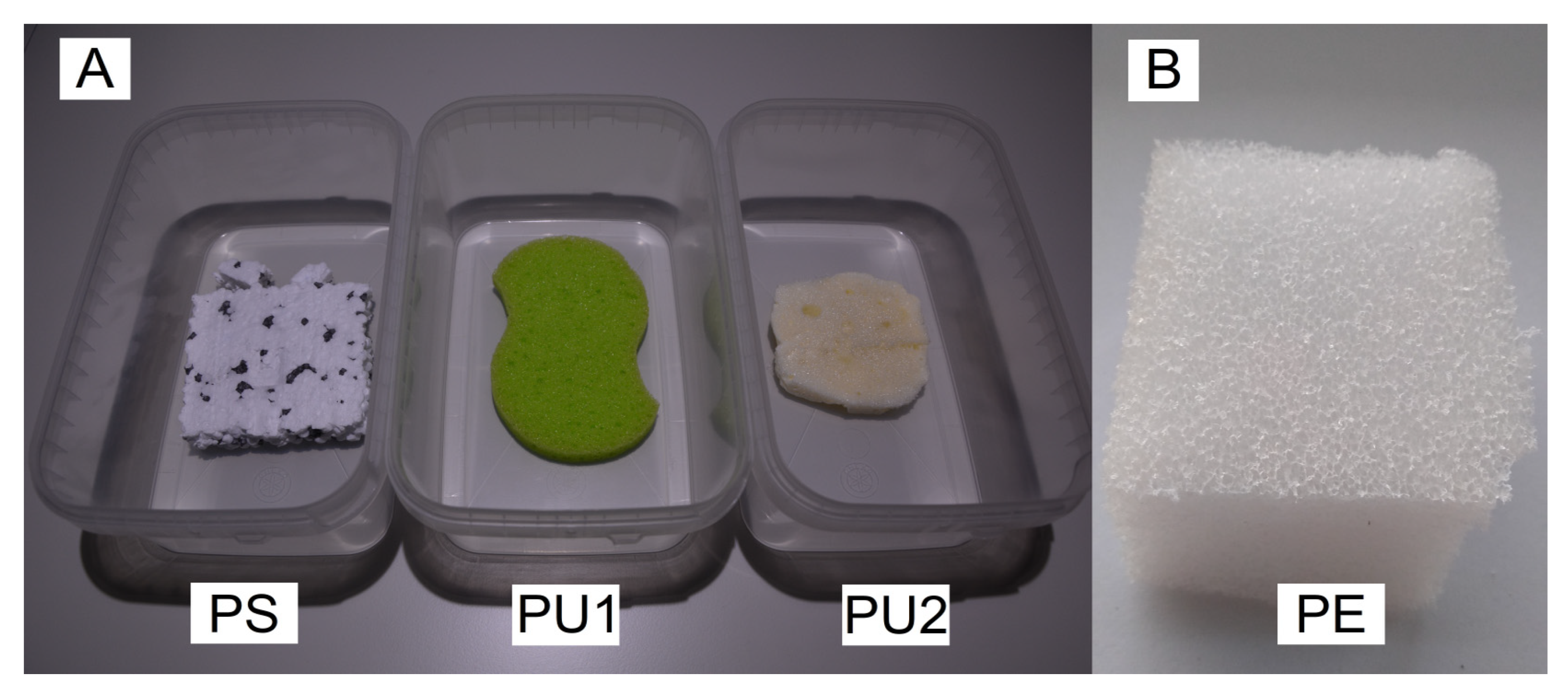

2.2. Plastic Waste

- Polystyrene (PS) in the form of Styrofoam, which is used for insulating building elevations;

- Polyurethane foam (PU1)—in the form of kitchen sponges;

- Polyurethane thermal insulation foam (PU2)—consisting of polyphenylpolyisocyanate polymethylene, according to information from the producer (SOUDAL Sp. z.o.o, Poland);

- Polyethylene foam (PE)—which is used as filling material in packages, e.g., to protect electrical equipment during transport.

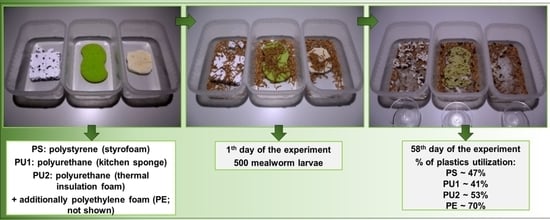

2.3. Experimental Procedure

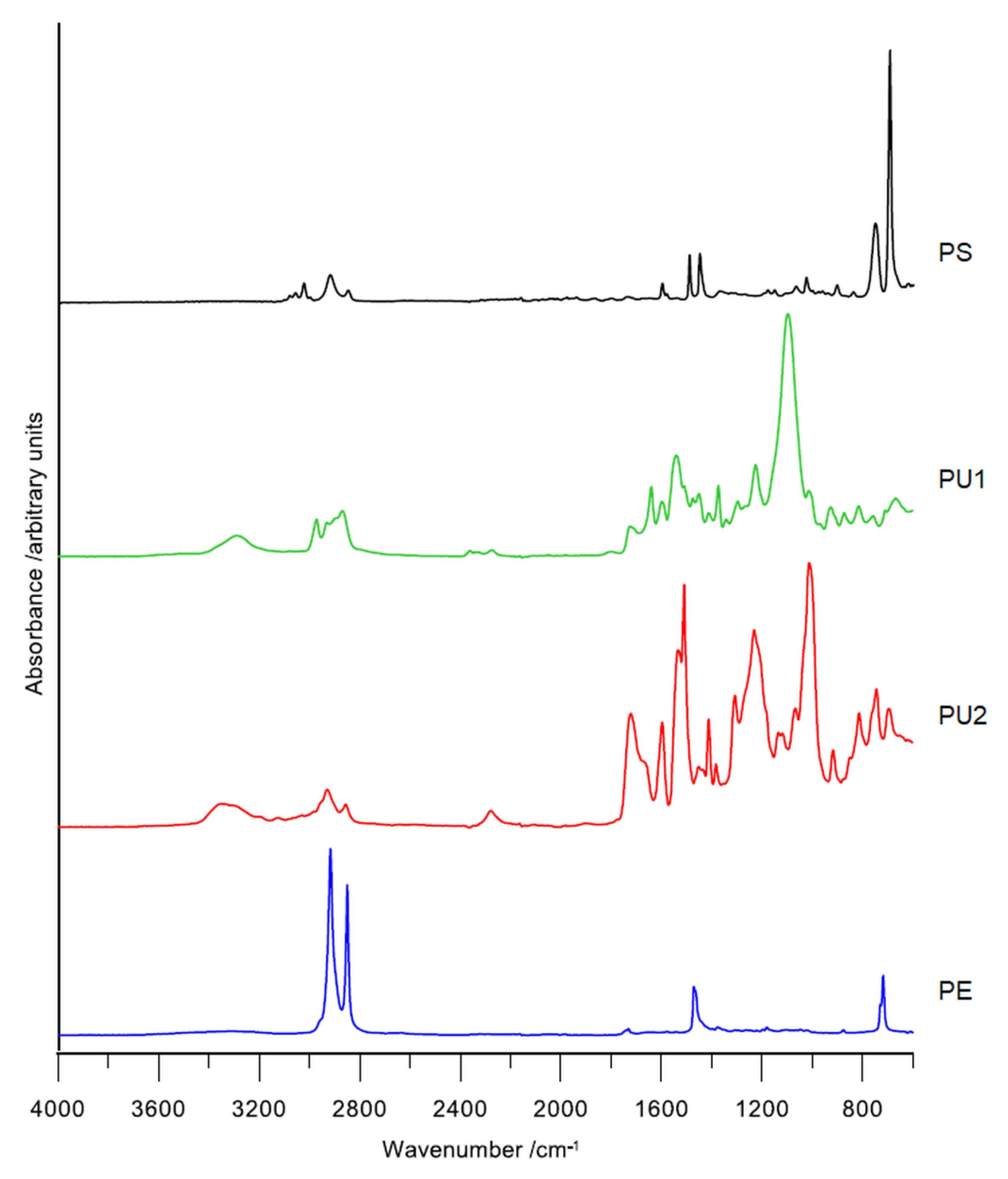

2.4. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) of Plastics

2.5. Energy Dispersive X-ray Fluorescence (EDXRF)

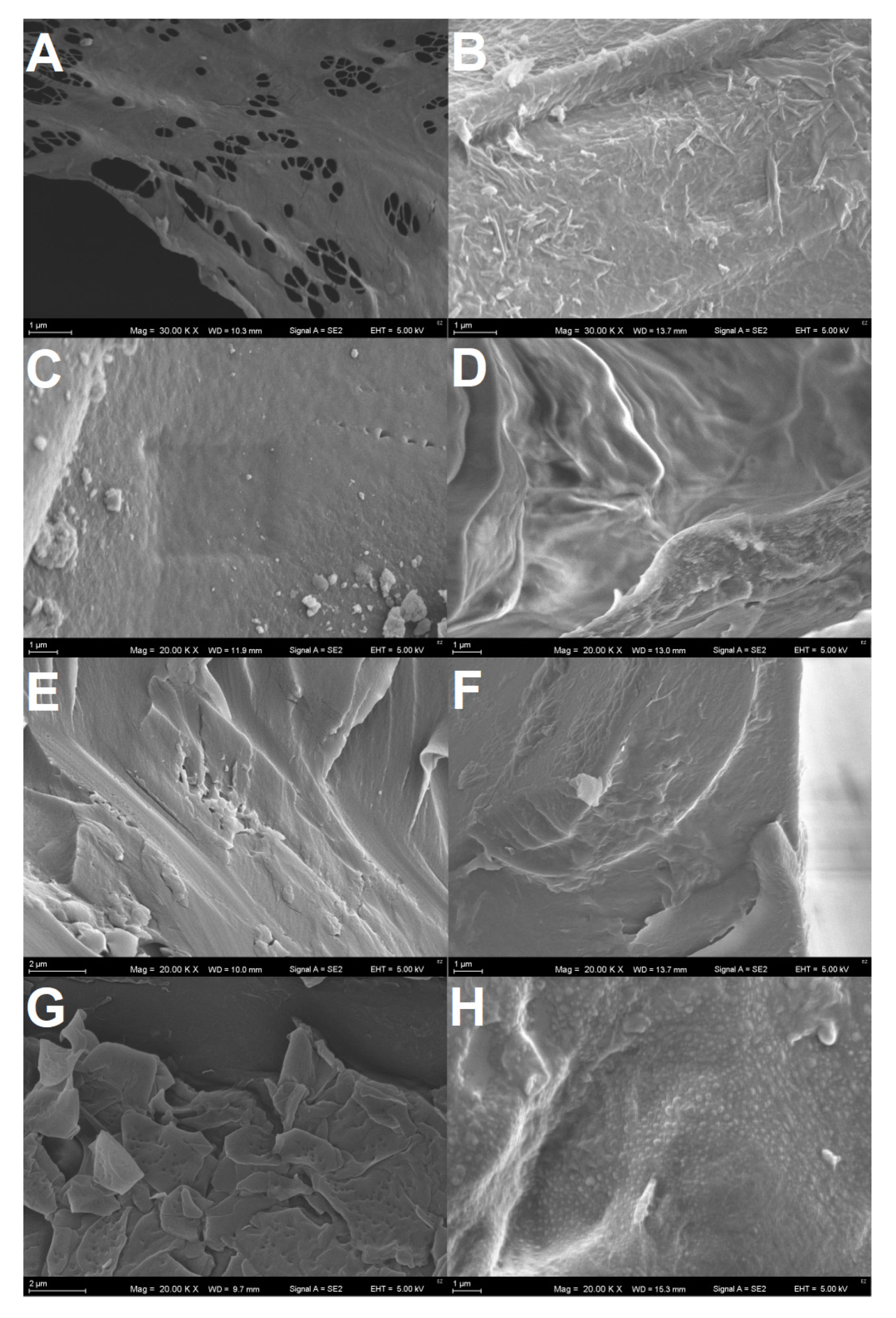

2.6. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

2.7. Photography and Time-Lapse Movie of Utilization

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Rate of PS, PU1, PU2, and PE Consumption by Mealworms

3.2. Morphological Parameters of Mealworm Larvae

3.3. Elements Content in the Plastics

3.4. Scanning Electron Microphotography of the Plastics Surfaces

3.5. Time-Lapse Movie of Utilization

4. Discussion

4.1. Rate of PS, PU1, PU2, and PE Consumption by Mealworms

4.2. Morphological Parameters of Mealworm Larvae

4.3. Elements in the Plastics

4.4. Polymers Surface Alterations Visualized by SEM

4.5. Time-Lapse Movie of Biodegradation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Plastics-the Facts 2020. An analysis of European Plastics Production, Demand and Waste Data. Plastics Europe, Association of Plastics Manufacturers. 2020. Available online: https://www.plasticseurope.org/download_file/force/4261/181 (accessed on 16 December 2020).

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Lavender Law, K. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science (80-) 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosior, E.; Mitchell, J. Current Industry Position on Plastic Production and Recycling; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; ISBN 9780128178805. [Google Scholar]

- Achilias, D.S.; Roupakias, C.; Megalokonomos, P.; Lappas, A.A.; Antonakou, E.V. Chemical recycling of plastic wastes made from polyethylene (LDPE and HDPE) and polypropylene (PP). J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 149, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anuar Sharuddin, S.D.; Abnisa, F.; Wan Daud, W.M.A.; Aroua, M.K. A review on pyrolysis of plastic wastes. Energy Convers. Manag. 2016, 115, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiemchaisri, C.; Charnnok, B.; Visvanathan, C. Recovery of plastic wastes from dumpsite as refuse-derived fuel and its utilization in small gasification system. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 1522–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokiwa, Y.; Calabia, B.P. Degradation of microbial polyesters. Biotechnol. Lett. 2004, 26, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, H.; Gupta, R.; Tiwari, A. Communities of microbial enzymes associated with biodegradation of plastics. J. Polym. Environ. 2013, 21, 575–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T.; Shahid, M.; Azeem, F.; Rasul, I.; Shah, A.A.; Noman, M.; Hameed, A.; Manzoor, N.; Manzoor, I.; Muhammad, S. Biodegradation of plastics: Current scenario and future prospects for environmental safety. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 7287–7298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadad, D.; Geresh, S.; Sivan, A. Biodegradation of polyethylene by the thermophilic bacterium Brevibacillus borstelensis. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2005, 98, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomita, K.; Kuroki, Y.; Nagai, K. Isolation of thermophiles degrading poly(L-lactic acid). J. Biosci. Bioeng. 1999, 87, 752–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obradors, N.; Aguilar, J. Efficient biodegradation of high-molecular-weight polyethylene glycols by pure cultures of Pseudomonas stutzeri. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1991, 57, 2383–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Walter, T.; Augusta, J.; Müller, R.J.; Widdecke, H.; Klein, J. Enzymatic degradation of a model polyester by lipase from Rhizopus delemar. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 1995, 17, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishide, H.; Toyota, K.; Kimura, M. Effects of soil temperature and anaerobiosis on degradation of biodegradable plastics in soil and their degrading microorganisms. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 1999, 45, 963–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billen, P.; Khalifa, L.; Van Gerven, F.; Tavernier, S.; Spatari, S. Technological application potential of polyethylene and polystyrene biodegradation by macro-organisms such as mealworms and wax moth larvae. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 735, 139521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bożek, M.; Hanus-Lorenz, B.; Rybak, J. The studies on waste biodegradation by Tenebrio molitor. E3S Web Conf. 2017, 17, 00011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Przemieniecki, S.W.; Kosewska, A.; Ciesielski, S.; Kosewska, O. Changes in the gut microbiome and enzymatic profile of Tenebrio molitor larvae biodegrading cellulose, polyethylene and polystyrene waste. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 256, 113265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbanek, A.K.; Rybak, J.; Wróbel, M.; Leluk, K.; Mirończuk, A.M. A comprehensive assessment of microbiome diversity in Tenebrio molitor fed with polystyrene waste. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 262, 114281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Tao, H.; Wong, M.H. Feeding and metabolism effects of three common microplastics on Tenebrio molitor L. Environ. Geochem. Health 2019, 41, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, J.; Wu, W.M.; Zhao, J.; Song, Y.; Gao, L.; Yang, R.; Jiang, L. Biodegradation and mineralization of polystyrene by plastic-eating mealworms: Chemical and physical characterization and isotopic tests. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 12080–12086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Xia, M. Biodegradation and mineralization of polystyrene by plastic-eating superworms Zophobas atratus. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 708, 135233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelkheir, M.G.; Visconte, L.Y.; Oliveira, G.E.; Toledo Filho, R.D.; Souza, F.G. The biodegradative effect of Tenebrio molitor Linnaeus larvae on vulcanized SBR and tire crumb. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 649, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulhay, H.S. Biodegradation of plastic wastes by confused flour beetle Tribolium confusum Jacquelin du Val larvae. Asian J. Agric. Biol. 2020, 8, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, Y.; Ekaterina, P.; Yang, S.S.; Lu, B.; Liu, B.; Ren, N.; Corvini, P.F.X.; Xing, D. Biodegradation of polyethylene and polystyrene by greater wax moth larvae (Galleria mellonella L.) and the effect of co-diet supplementation on the core gut microbiome. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 2821–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gao, D.; Li, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Li, L.; Lin, H.; Bi, Q.; Zhao, Y. Biodegradation of polyethylene microplastic particles by the fungus Aspergillus flavus from the guts of wax moth Galleria mellonella. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesti, S.S.; Thimmappa, C.S. First report on biodegradation of low density polyethylene by rice moth larvae, Corcyra cephalonica (stainton). Holist. Approach Environ. 2019, 9, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ewuim, S. Entomoremediation—A novel in-Situ bioremediation approach. Anim. Res. Int. 2013, 10, 1681–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulak, P.; Polakowski, C.; Nowak, K.; Waśko, A.; Wiącek, D.; Bieganowski, A. Hermetia illucens as a new and promising species for use in entomoremediation. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 633, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Qiu, R.; Hu, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Wu, W.M.; He, D. Biodegradation and disintegration of expanded polystyrene by land snails Achatina fulica. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 746, 141289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariod, A.A.; Mirghani, M.E.S.; Hussein, I. Tenebrio molitor Mealworm. Unconv. Oilseeds Oil Sources 2017, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finke, M.D. Complete nutrient content of four species of commercially available feeder insects fed enhanced diets during growth. Zoo Biol. 2015, 34, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jajic, I.; Popovic, A.; Urosevic, M.; Krstovic, S.; Petrovic, M.; Guljas, D.; Samardzic, M. Fatty and amino acid profile of mealworm larvae (Tenebrio molitor L.). Biotechnol. Anim. Husb. 2020, 36, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, Z. The Nutritional Potential of Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia Illucens) Larvae for Layer Hens. Ph.D. Thesis, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2018; pp. 1–103. [Google Scholar]

- Rivero Pino, F.; Pérez Gálvez, R.; Espejo Carpio, F.J.; Guadix, E.M. Evaluation of: Tenebrio molitor protein as a source of peptides for modulating physiological processes. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 4376–4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houben, D.; Daoulas, G.; Faucon, M.P.; Dulaurent, A.M. Potential use of mealworm frass as a fertilizer: Impact on crop growth and soil properties. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bulak, P.; Proc, K.; Pawłowska, M.; Kasprzycka, A.; Berus, W.; Bieganowski, A. Biogas generation from insects breeding post production wastes. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, G.T.; Yuk, H.G.; Lee, S.J.; Chung, Y.H.; Jang, H.S.; Yoo, J.S.; Cho, K.H.; Kong, H.; Shin, D. Mealworm larvae (Tenebrio molitor L.) exuviae as a novel prebiotic material for BALB/c mouse gut microbiota. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2020, 29, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabbou, S.; Ferrocino, I.; Gasco, L.; Schiavone, A.; Trocino, A.; Xiccato, G.; Barroeta, A.C.; Maione, S.; Soglia, D.; Biasato, I.; et al. Antimicrobial effects of black soldier fly and yellow mealworm fats and their impact on gut microbiota of growing rabbits. Animals 2020, 10, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saenz-Mendoza, A.I.; Zamudio-Flores, P.B.; García-Anaya, M.C.; Velasco, C.R.; Acosta-Muñiz, C.H.; de Jesús Ornelas-Paz, J.; Hernández-González, M.; Vargas-Torres, A.; Aguilar-González, M.Á.; Salgado-Delgado, R. Characterization of insect chitosan films from Tenebrio molitor and Brachystola magna and its comparison with commercial chitosan of different molecular weights. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 160, 953–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, L.; Mei, Q.; Dong, B.; Dai, X.; Ding, G.; Zeng, E.Y. Microplastics in sewage sludge from the wastewater treatment plants in China. Water Res. 2018, 142, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.S.; Brandon, A.M.; Andrew Flanagan, J.C.; Yang, J.; Ning, D.; Cai, S.Y.; Fan, H.Q.; Wang, Z.Y.; Ren, J.; Benbow, E.; et al. Biodegradation of polystyrene wastes in yellow mealworms (larvae of Tenebrio molitor Linnaeus): Factors affecting biodegradation rates and the ability of polystyrene-fed larvae to complete their life cycle. Chemosphere 2018, 191, 979–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.Y.; Su, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhou, X.; Benbow, M.E.; Criddle, C.S.; Wu, W.M.; Zhang, Y. Biodegradation of polystyrene by Dark (Tenebrio obscurus) and Yellow (Tenebrio molitor) Mealworms (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 5256–5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandon, A.M.; Gao, S.H.; Tian, R.; Ning, D.; Yang, S.S.; Zhou, J.; Wu, W.M.; Criddle, C.S. Biodegradation of polyethylene and plastic mixtures in mealworms (larvae of Tenebrio molitor) and effects on the gut microbiome. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 6526–6533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Yin, J.; Hao, W.; Jiao, M. Polyurethane foam induces epigenetic modification of mitochondrial DNA during different metamorphic stages of Tenebrio molitor. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 183, 109461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Nadir, S.; Mortimer, P.E.; Xu, J.; Gui, H.; Khan, A.; Iqbal, S.; Ye, L.; Shi, L. Biodegradation of polyester polyurethane by Aspergillus tubingensis. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 229, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Gao, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhuang, G.; Peng, X.; Wu, W.M.; Zhuang, X. Biodegradation of expanded polystyrene and low-density polyethylene foams in larvae of Tenebrio molitor Linnaeus (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae): Broad versus limited extent depolymerization and microbe-dependence versus independence. Chemosphere 2021, 262, 127818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.S.; Wu, W.M.; Brandon, A.M.; Fan, H.Q.; Receveur, J.P.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.Y.; Fan, R.; McClellan, R.L.; Gao, S.H.; et al. Ubiquity of polystyrene digestion and biodegradation within yellow mealworms, larvae of Tenebrio molitor Linnaeus (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). Chemosphere 2018, 212, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ranta-Korpi, M.; Vainikka, P.; Konttinen, J.; Saarimaa, A.; Rodriguez, M. Ash Forming Elements in Plastics and Rubbers; VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland: Espoo, Finland, 2014; ISBN 978-951-38-8158-0. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, A. Heavy metals, metalloids and other hazardous elements in marine plastic litter. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 111, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sing, H.; Jain, A. Ignition, combustion, toxicity, and fire retardancy of polyurethane foams: A comprehensive review. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2008, 111, 1115–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, H.G.; Samuel, E. Fluorenyl complexes of zirconium and hafnium as catalysts for olefin polymerization. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1998, 27, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.M.; Kim, H.R.; Jeon, E.; Yu, H.C.; Lee, S.; Li, J.; Kim, D.-H. Evaluation of the biodegradation efficiency of four various types of plastics by Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolated from the gut extract of superworms. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masykuri, M.; Widyasari, F. Surface morphology and biodegradation tests of polyurethane/clay rigid foam composites. J. Chem. Technol. Metall. 2021, 56, 744–753. [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa, T.; Kurauchi, T. Larval cannibalism and pupal defense against cannibalism in two species of tenebrionid beetles. Zool. Sci. 2009, 26, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter\Plastic Type | PS | PU1 | PU2 | PE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | ||||

| Mass of plastic [g] | 2.610 ± 0.001 | 2.611 ± 0.001 | 2.607 ± 0.001 | 2.608 ± 0.001 |

| Final | ||||

| Mass of plastic [g] | 1.225 ± 0.004 b,c,* | 1.390 ± 0.072 c,* | 1.070 ± 0.133 a,b,* | 0.790 ± 0.166 a,* |

| Utilization [w/w %] | 46.929 ± 0.124 a,b | 46.771 ± 2.734 a | 58.972 ± 5.146 c | 69.707 ± 6.341 c |

| Plastic remnants in frass [w/w %] | 31.697 ± 0.647 a | 45.353 ± 1.548 d | 41.724 ± 0.543 c | 38.977 ± 1.435 b |

| Parameter\Substrate | PS | PU1 | PU2 | PE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | ||||

| Mass of 1 larvae [g] | 0.098 ± 0.001 | 0.099 ± 0.001 | 0.099 ± 0.001 | 0.085 ± 0.002 |

| Length of 1 larvae [cm] | 2.413 ± 0.013 | 2.397 ± 0.060 | 2.367 ± 0.003 | 2.386 ± 0.047 |

| Final | ||||

| Mass of 1 larvae [g] | 0.080 ± 0.002 b,* | 0.071 ± 0.003 a,b,* | 0.073 ± 0.006 a,b,* | 0.064 ± 0.001 a,* |

| Length of 1 larvae [cm] | 2.262 ± 0.005 a,* | 2.173 ± 0.010 a,* | 2.264 ± 0.093 a | 2.229 ± 0.005 a,* |

| Mass of 1 adult [g] | 0.120 ± 0.001 b | 0.114 ± 0.008 b | 0.089 ± 0.001 a | 0.087 ± 0.007 a |

| Length of 1 adult [cm] | 1.617 ± 0.017 b | 1.450 ± 0.050 a | 1.459 ± 0.092 a | 1.322 ± 0.006a |

| % | PS | PU1 | PU2 | PE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | - | 0.437 ± 0.038 | - | 0.180 ± 0.029 |

| Ba | - | - | - | 0.029 ± 0.001 |

| Br | 0.412 ± 0.019 | - | 0.001 ± 0.001 | - |

| Ca | 0.020 ± 0.009 | 10.110 ± 0.301 | - | 1.381 ± 0.020 |

| Cl | 0.017 ± 0.001 | 0.224 ± 0.022 | 7.574 ± 0.141 | 0.017 ± 0.004 |

| Co | 0.002 ± 0.001 | - | - | - |

| Cr | 0.003 ± 0.001 | 0.008 ± 0.001 | 0.001 ± 0.000 | 0.004 ± 0.001 |

| Cu | 0.006 ± 0.000 | 0.013 ± 0.001 | 0.001 ± 0.000 | 0.006 ± 0.001 |

| Fe | 0.008 ± 0.002 | 0.021 ± 0.001 | 0.001 ± 0.000 | 0.006 ± 0.001 |

| Hf | 0.010 ± 0.001 | - | - | 0.012 ± 0.000 |

| K | 0.009 ± 0.005 | - | 0.004 ± 0.002 | 0.005 ± 0.001 |

| Mn | 0.003 ± 0.001 | 0.007 ± 0.001 | - | 0.002 ± 0.000 |

| Ni | - | 0.001 ± 0.001 | - | - |

| P | - | - | 1.379 ± 0.035 | - |

| S | 0.023 ± 0.002 | 0.008 ± 0.005 | - | 0.012 ± 0.003 |

| Si | 0.049 ± 0.005 | 0.358 ± 0.027 | 0.072 ± 0.004 | 0.029 ± 0.004 |

| Sn | - | 0.070 ± 0.000 | - | - |

| Ti | - | - | - | 0.004 ± 0.000 |

| Zn | 0.003 ± 0.001 | 0.003 ± 0.000 | - | 0.007 ± 0.000 |

| Plastic | Consumption Rate [µg·day−1·larvae−1] | Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene (PS) | T. molitor from Guangzhou: 268.3 T. molitor from Tai’an: 160.5 T. molitor from Shenzhen: 239.9 | [19] |

| 119.9 | [20] | |

| T. molitor, PS alone: 243.0 T. molitor, PS + wheat bran: 332.3 T. obscurus, PS alone: 324.4 T. obscurus, PS + corn flour: 392.4 | [40] | |

| PS alone: 118.0–222.0 PS + soy protein: 491.0 PS + wheat bran: 441.0 | [46] | |

| PS alone: 148.4 PS + wheat bran: 255.2 | [47] | |

| 77.4 a 174.7 b | This research a | |

| Polyurethane (PU) | PU1: 73.9 a 168.7 b PU2: 87.5 a 158.9 b | This research a |

| Polyethylene (PE) | T. molitor from Guangzhou: 172.2 T. molitor from Tai’an: 102.7 T. molitor from Shenzhen: 138.6 | [19] |

| PE alone: 226.6 PE + wheat bran: 286.5 | [47] | |

| 86.7 a 122.4 b | This research a |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bulak, P.; Proc, K.; Pytlak, A.; Puszka, A.; Gawdzik, B.; Bieganowski, A. Biodegradation of Different Types of Plastics by Tenebrio molitor Insect. Polymers 2021, 13, 3508. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13203508

Bulak P, Proc K, Pytlak A, Puszka A, Gawdzik B, Bieganowski A. Biodegradation of Different Types of Plastics by Tenebrio molitor Insect. Polymers. 2021; 13(20):3508. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13203508

Chicago/Turabian StyleBulak, Piotr, Kinga Proc, Anna Pytlak, Andrzej Puszka, Barbara Gawdzik, and Andrzej Bieganowski. 2021. "Biodegradation of Different Types of Plastics by Tenebrio molitor Insect" Polymers 13, no. 20: 3508. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13203508

APA StyleBulak, P., Proc, K., Pytlak, A., Puszka, A., Gawdzik, B., & Bieganowski, A. (2021). Biodegradation of Different Types of Plastics by Tenebrio molitor Insect. Polymers, 13(20), 3508. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13203508