Chemical Recycling of Bio-Based Epoxy Matrices Based on Precursors Derived from Waste Flour: Recycled Polymers Characterization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Epoxy Resin Systems Formulation

2.3. Chemical Recycling Process

2.4. Recycled Polymers: Characterization Techniques

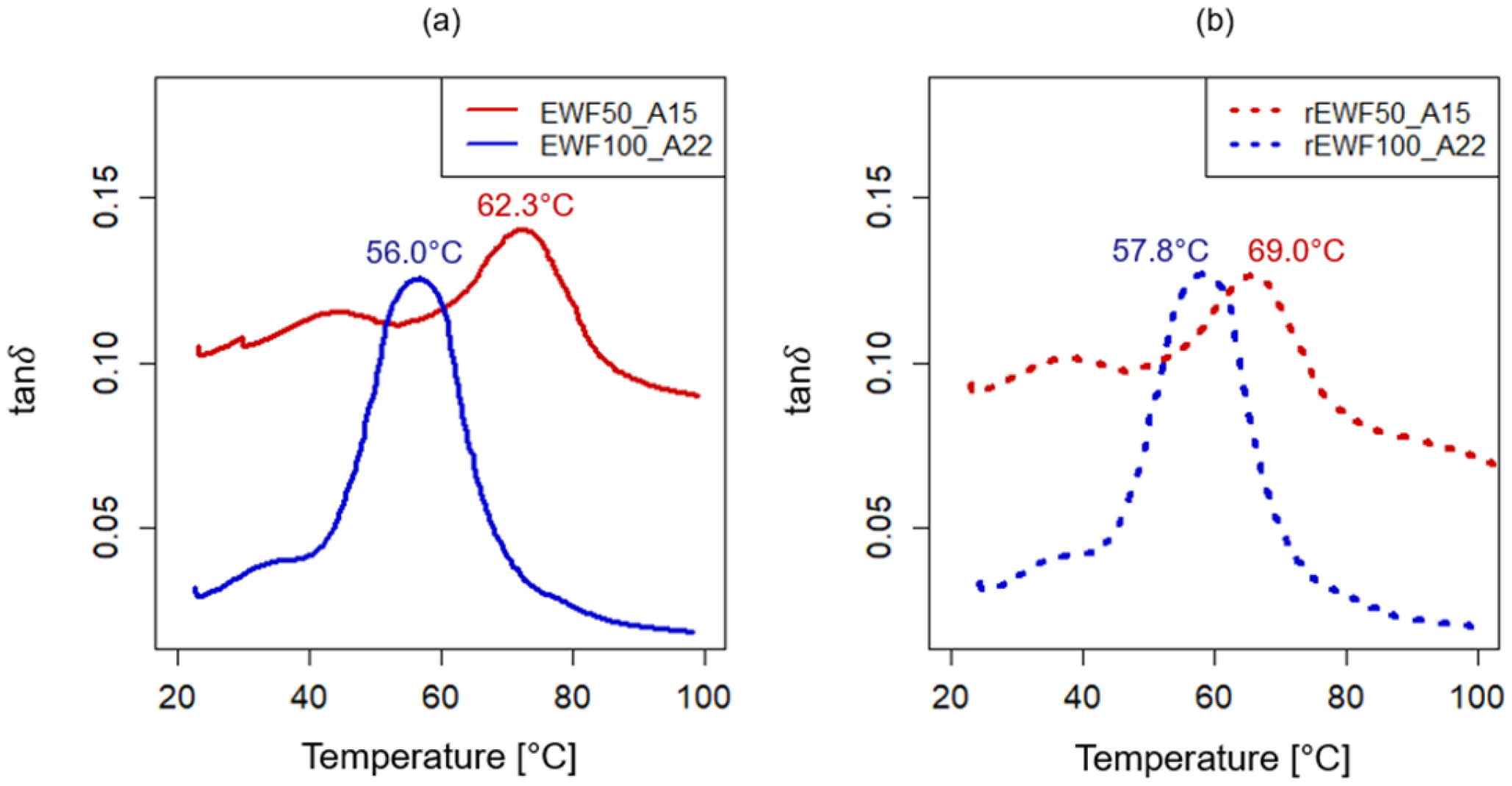

2.4.1. Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

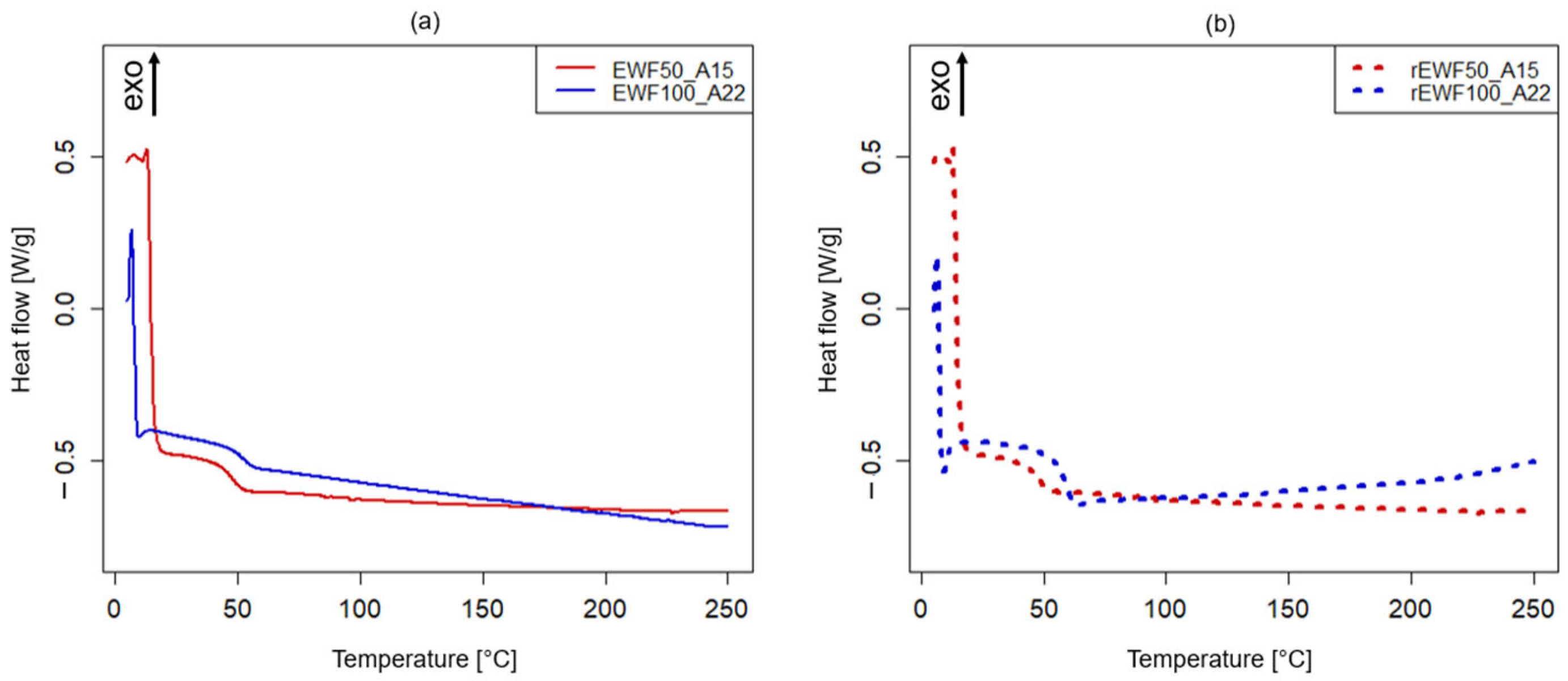

2.4.2. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

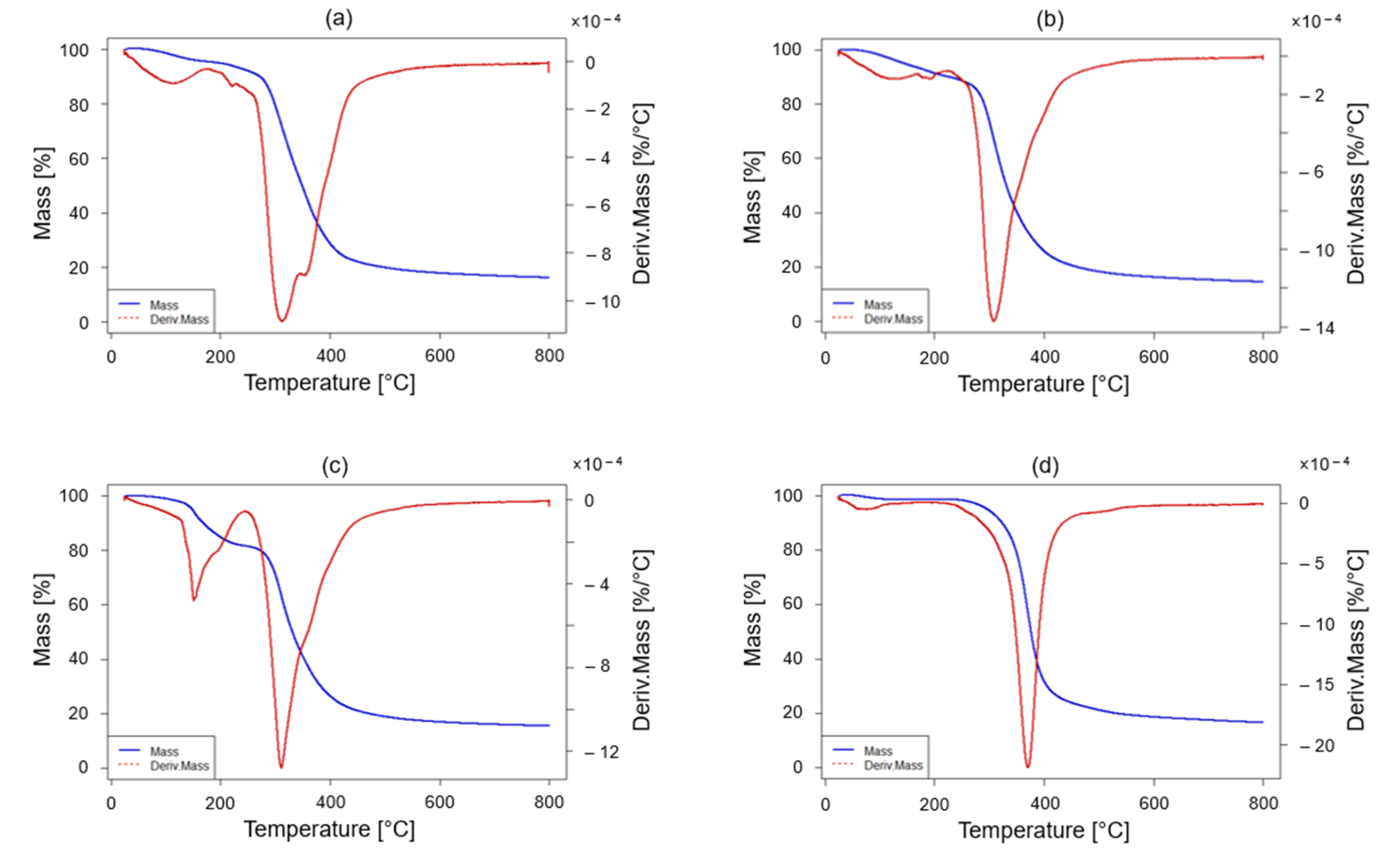

2.4.3. Termogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

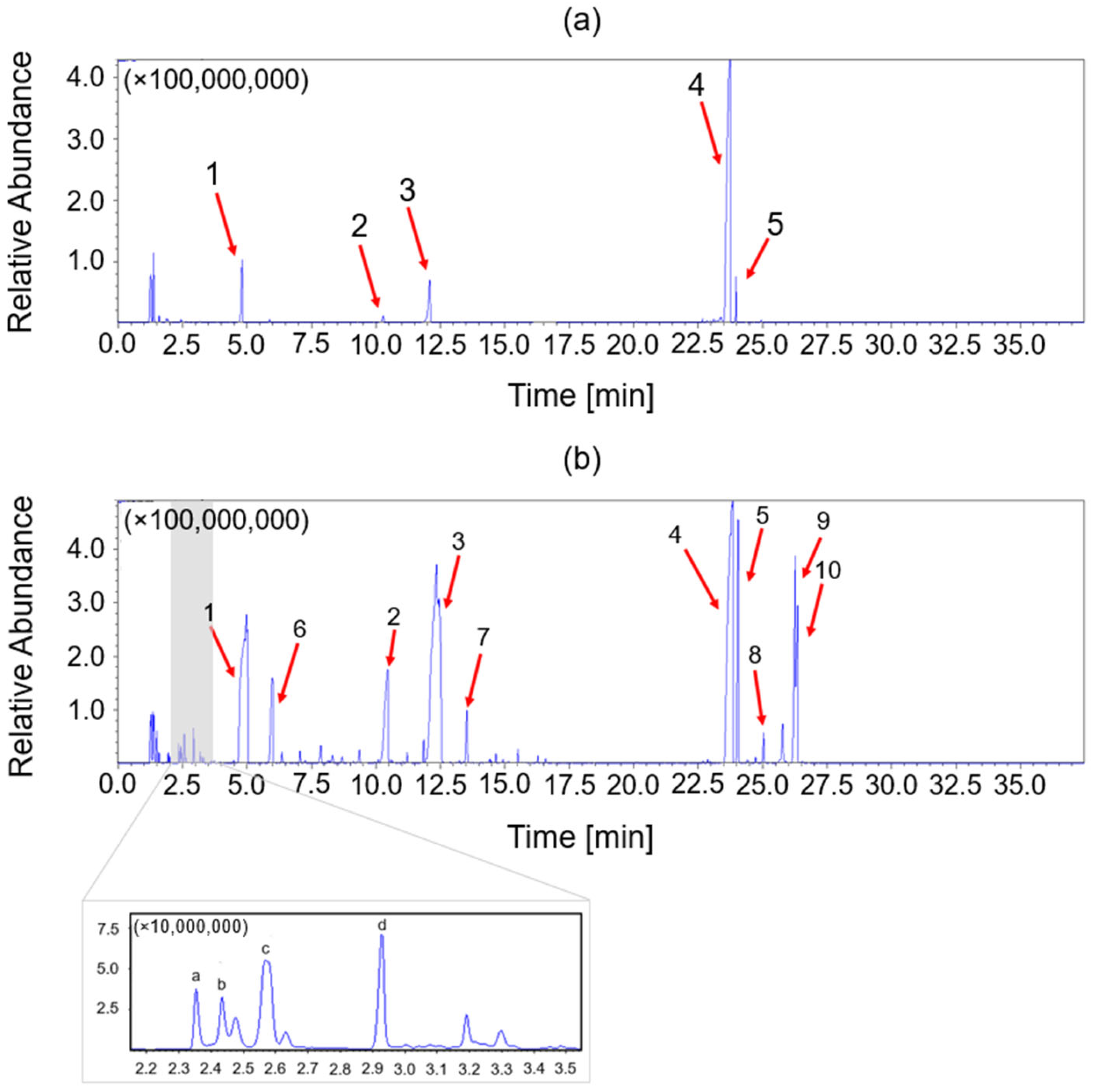

2.4.4. Pyrolysis–Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (Py-GC/MS)

2.4.5. Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectroscopy (MALDI-TOF-MS)

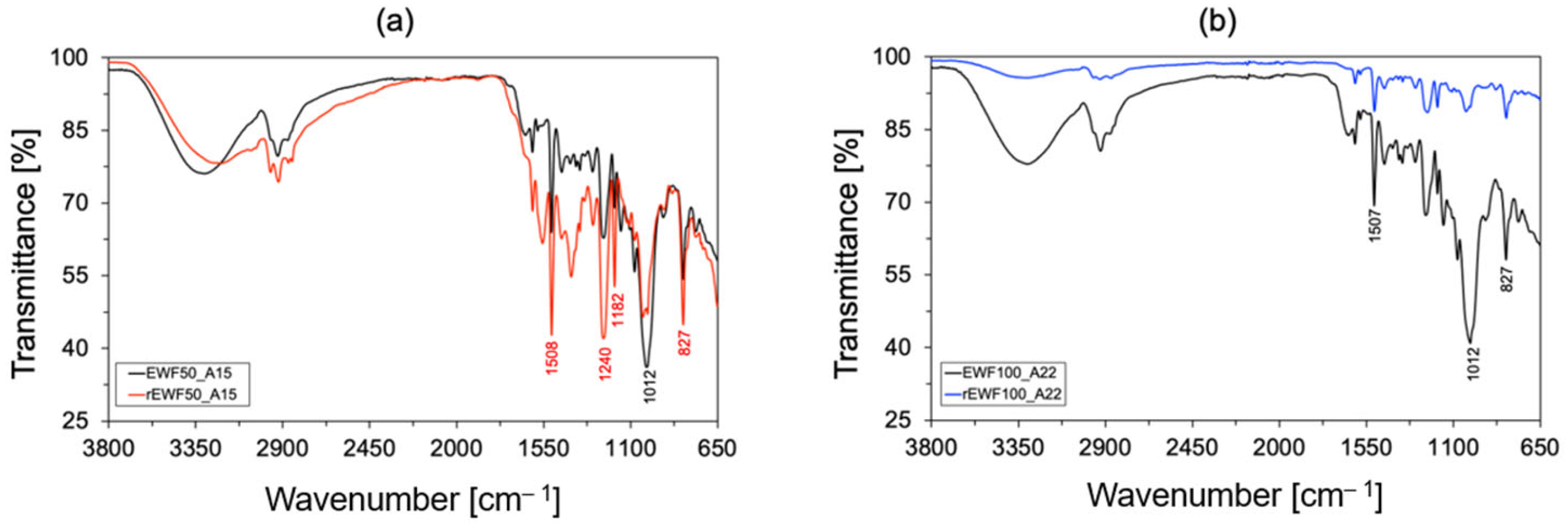

2.4.6. FT-IR Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

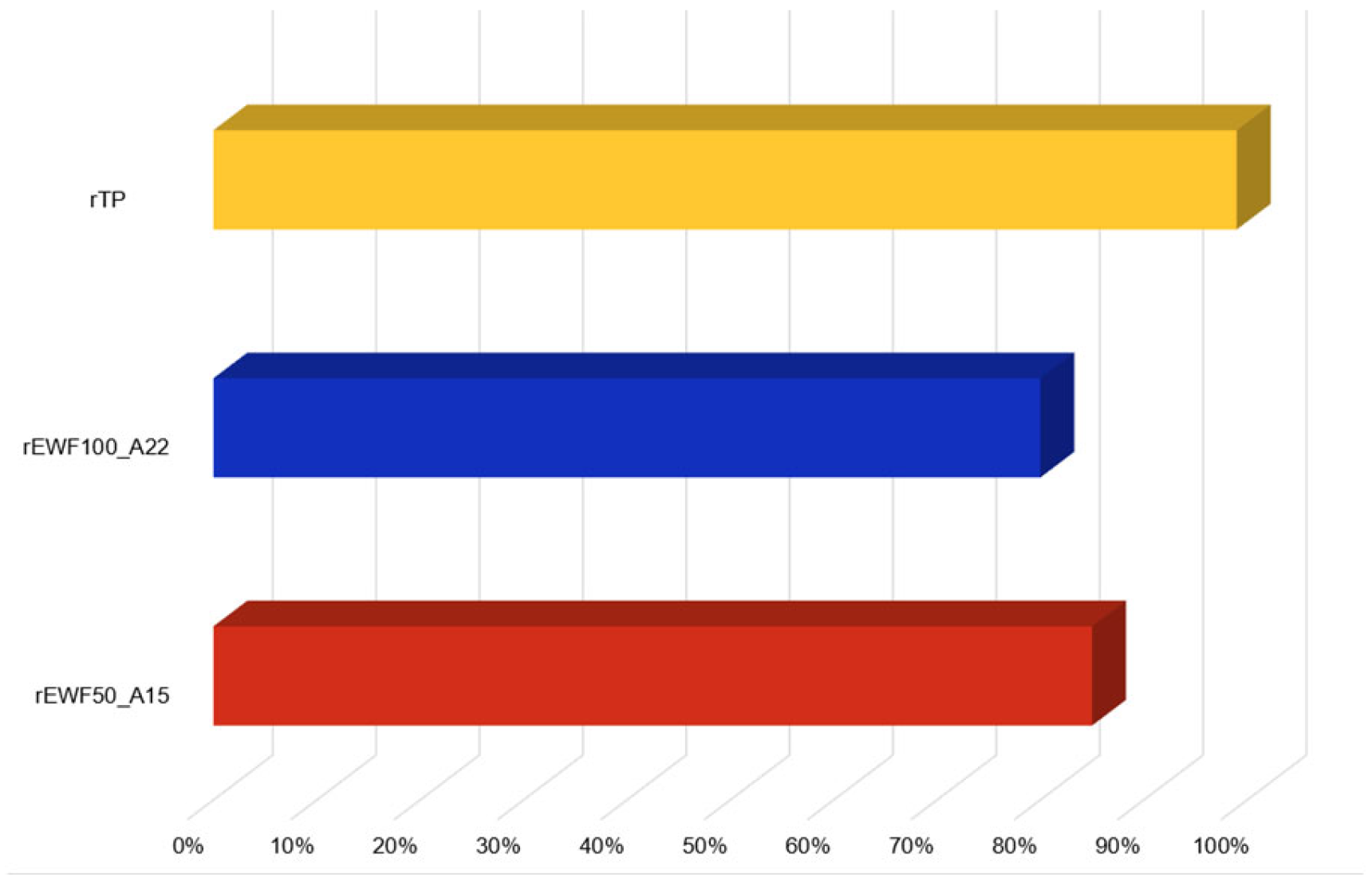

3.1. Chemical Recycling Process Results and Process Yield

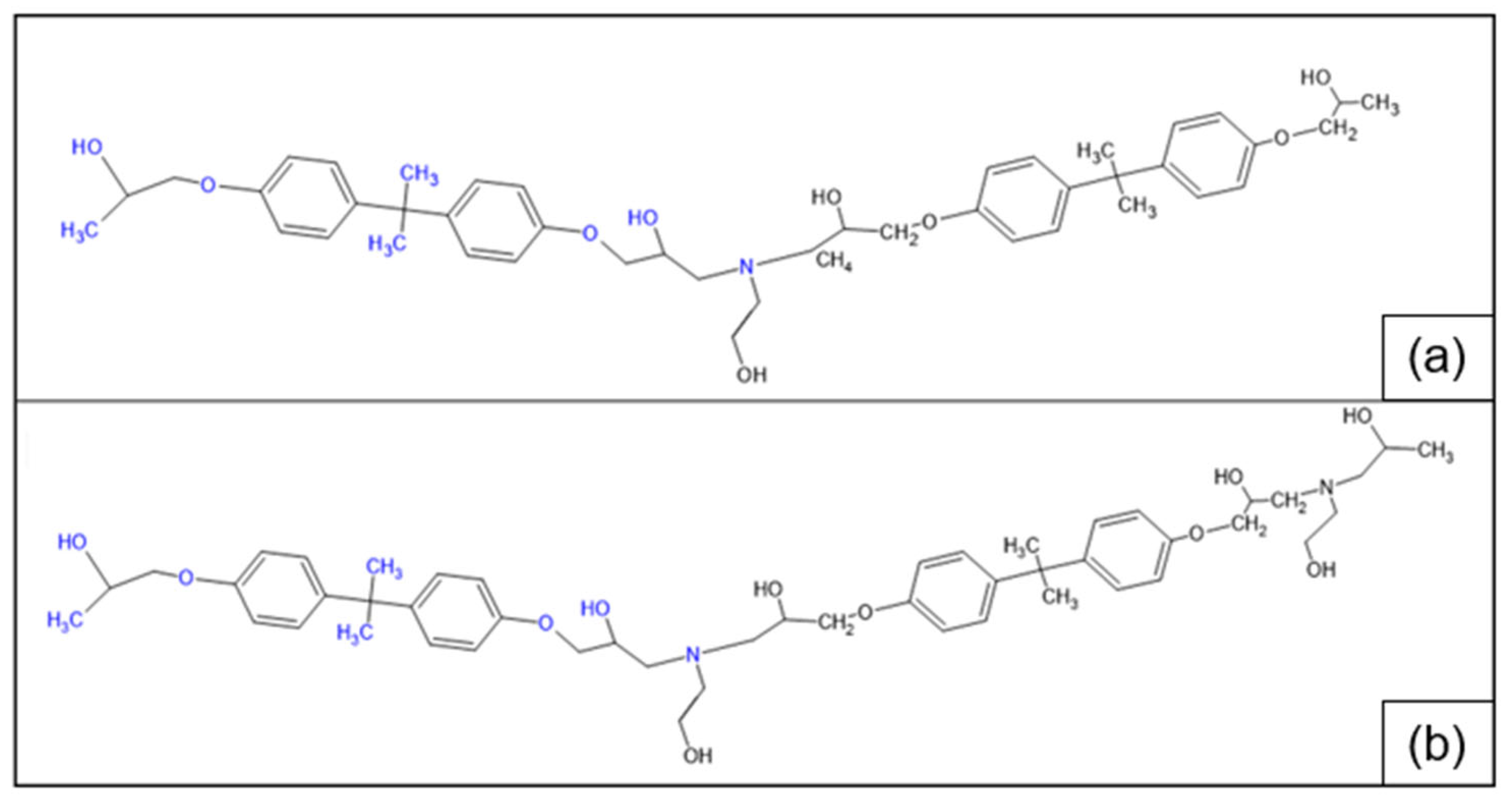

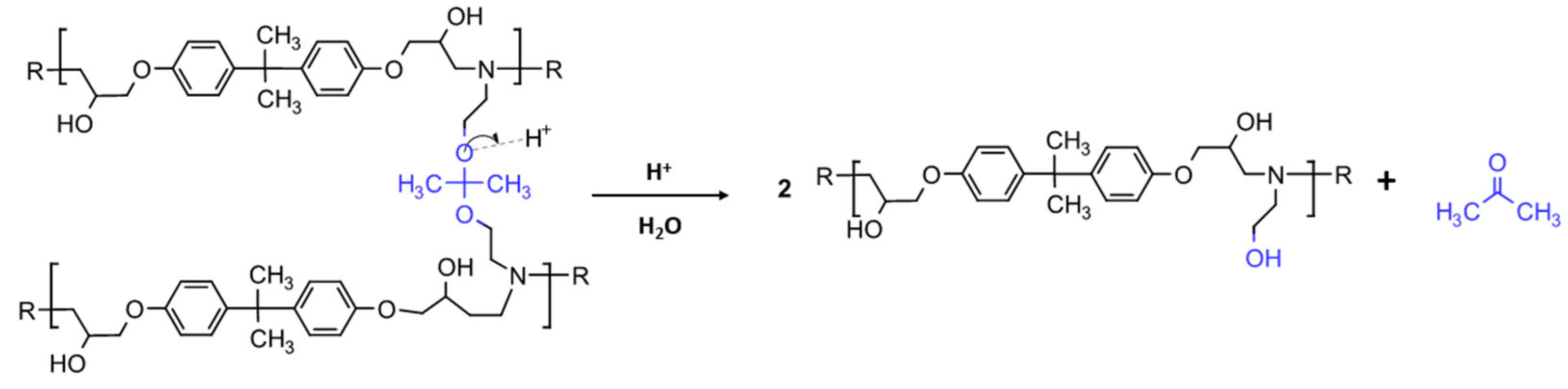

3.2. Chemical and Thermo-Mechanical Properties of the Recycled Product

4. Conclusions

- EWF50_A15, containing 50%wt of PolarBear with 50%wt of EWF, and RecyclamineTM R*101 equal to 15 phr;

- EWF100_A22, obtained by directly mixing only the EWF with a content of RecyclamineTM R*101 equal to 22 phr.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rani, M.; Choudhary, P.; Krishnan, V.; Zafar, S. A Review on Recycling and Reuse Methods for Carbon Fiber/Glass Fiber Composites Waste from Wind Turbine Blades. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 215, 108768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompidou, S.; Prinçaud, M.; Perry, N.; Leray, D. Recycling of Carbon Fiber. Identification of Bases for a Synergy between Recyclers and Designers. In Proceedings of the ASME 2012 11th Biennial Conference on Engineering Systems Design and Analysis, ESDA 2012, Nantes, France, 2–4 July 2012; Volume 3, pp. 551–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Q.; An, L.; Hu, Z.; Kuang, X. Fast and Sustainable Recycling of Epoxy and Composites Using Mixed Solvents. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2022, 199, 109895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, F.L.; Li, X.; Park, S.J. Synthesis and Application of Epoxy Resins: A Review. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015, 29, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, I.; Kausar, A.; Muhammad, B. Epoxy Resin Composite Reinforced with Carbon Fiber and Inorganic Filler: Overview on Preparation and Properties. Polym. Plast. Technol. Eng. 2016, 55, 1653–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitta, L.; Cutuli, E.; Celano, G.; Tosto, C.; Sanalitro, D.; Guarino, F.; Cicala, G.; Bucolo, M. Projection Micro-Stereolithography to Manufacture a Biocompatible Micro-Optofluidic Device for Cell Concentration Monitoring. Polymers 2023, 15, 4461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitta, L.; Cutuli, E.; Celano, G.; Tosto, G.C.; Guarino, F.; Cicala, G.; Bucolo, M. Monolithic 3D Printed Micro-Optofluidic Device for Two-Phase Flow Monitoring and Bioapplications. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference And Exposition On Electric And Power Engineering (EPEi), Iasi, Romania, 17–19 October 2024; pp. 642–647. [Google Scholar]

- Cutuli, E.; Sanalitro, D.; Stella, G.; Saitta, L.; Bucolo, M. A 3D-Printed Micro-Optofluidic Chamber for Fluid Characterization and Microparticle Velocity Detection. Micromachines 2023, 14, 2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitta, L.; Cutuli, E.; Celano, G.; Tosto, C.; Stella, G.; Cicala, G.; Bucolo, M. A Regression Approach to Model Refractive Index Measurements of Novel 3D Printable Photocurable Resins for Micro-Optofluidic Applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grand View Research. Epoxy Resin Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Application (Adhesives, Electrical & Electronics, Paints & Coatings, Wind Turbines, Composites, Construction), By Region, And Segment Forecasts, 2022–2030; Report ID: 978-1-68038-171-9; Research and Markets: Dublin, Ireland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Lin, G.; Vaidya, U.; Wang, H. Past, Present and Future Prospective of Global Carbon Fibre Composite Developments and Applications. Compos. Part B Eng. 2023, 250, 110463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subadra, S.P.; Griskevicius, P. Sustainability of Polymer Composites and Its Critical Role in Revolutionising Wind Power for Green Future. Sustain. Technol. Green Econ. 2021, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallivokas, S.V.; Sgouros, A.P.; Theodorou, D.N. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of EPON-862/DETDA Epoxy Networks: Structure, Topology, Elastic Constants, and Local Dynamics. Soft Matter 2019, 15, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavrilov, A.A.; Komarov, P.V.; Khalatur, P.G. Thermal Properties and Topology of Epoxy Networks: A Multiscale Simulation Methodology. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Li, M.; Lu, Z.-Y.; Zhang, Z.-G.; Sun, C.-C.; Cui, T. Multiscale Simulation Study on the Curing Reaction and the Network Structure in a Typical Epoxy System. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 8650–8660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanaoka, T.; Arao, Y.; Kayaki, Y.; Kuwata, S.; Kubouchi, M. Analysis of Nitric Acid Decomposition of Epoxy Resin Network Structures for Chemical Recycling. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2021, 186, 109537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, W.; Susa, A.; Blaauw, R.; Molenveld, K.; Knoop, R.J.I. A Review on the Potential and Limitations of Recyclable Thermosets for Structural Applications. Polym. Rev. 2020, 60, 359–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharde, S.; Kandasubramanian, B. Mechanothermal and Chemical Recycling Methodologies for the Fibre Reinforced Plastic (FRP). Environ. Technol. Innov. 2019, 14, 100311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, G.G.M.; de Paiva, J.M.F.; do Carmo, J.B.; Botaro, V.R. Recycling of Carbon Fibers Inserted in Composite of DGEBA Epoxy Matrix by Thermal Degradation. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2014, 109, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolai, G.; Bôas, A.P.; Méndez, M.O.; Taranto, O.P. Thermochemical Recycling of Epoxy Resin Composites Reinforced with Carbon Fiber. J. Compos. Mater. 2023, 57, 3201–3212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauklis, A.E.; Karl, C.W.; Gagani, A.I.; Jørgensen, J.K. Composite Material Recycling Technology—State-of-the-Art and Sustainable Development for the 2020s. J. Compos. Sci. 2021, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatziparaskeva, G.; Papamichael, I.; Voukkali, I.; Loizia, P.; Sourkouni, G.; Argirusis, C.; Zorpas, A.A. End-of-Life of Composite Materials in the Framework of the Circular Economy. Microplastics 2022, 1, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveux, G.; Dandy, L.O.; Leeke, G.A. Current Status of Recycling of Fibre Reinforced Polymers: Review of Technologies, Reuse and Resulting Properties. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2015, 72, 61–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Job, S. Recycling Composites Commercially. Reinf. Plast. 2014, 58, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, M.; Choudhary, P.; Krishnan, V.; Zafar, S. Development of Sustainable Microwave-Based Approach to Recover Glass Fibers for Wind Turbine Blades Composite Waste. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 179, 106107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.Y.; Arif, Z.U.; Hossain, M.; Umer, R. Recycling of Wind Turbine Blades through Modern Recycling Technologies: A Road to Zero Waste. Renew. Energy Focus. 2023, 44, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybicka, J.; Tiwari, A.; Leeke, G.A. Technology Readiness Level Assessment of Composites Recycling Technologies. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 1001–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakdel, E.; Kashi, S.; Varley, R.; Wang, X. Recent Progress in Recycling Carbon Fibre Reinforced Composites and Dry Carbon Fibre Wastes. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 166, 105340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irisawa, T.; Aratake, R.; Hanai, M.; Sugimoto, Y.; Tanabe, Y. Elucidation of Damage Factors to Recycled Carbon Fibers Recovered from CFRPs by Pyrolysis for Finding Optimal Recovery Conditions. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 218, 108939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Krishnan, S. Recycling of Carbon Fiber with Epoxy Composites by Chemical Recycling for Future Perspective: A Review. Chem. Pap. 2020, 74, 3785–3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Kim, D.H.; Park, J.J.; You, N.H.; Goh, M. Fast Chemical Recycling of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Plastic at Ambient Pressure Using an Aqueous Solvent Accelerated by a Surfactant. Waste Manag. 2020, 118, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dattilo, S.; Cicala, G.; Riccobene, P.M.; Puglisi, C.; Saitta, L. Full Recycling and Re-Use of Bio-Based Epoxy Thermosets: Chemical and Thermomechanical Characterization of the Recycled Matrices. Polymers 2022, 14, 4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saitta, L.; Prasad, V.; Tosto, C.; Murphy, N.; Ivankovic, A.; Cicala, G.; Scarselli, G. Characterization of Biobased Epoxy Resins to Manufacture Eco-composites Showing Recycling Properties. Polym. Compos. 2022, 43, 9179–9192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, X.; Ge, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Li, J.; Deng, T.; Qin, Z.; Hou, X. Chemical Recycling of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Epoxy Resin Composites via Selective Cleavage of the Carbon-Nitrogen Bond. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 3332–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, P.L.; Zhu, Y.K.; Ding, J.P.; Xue, L.X.; Wang, Y.Z. A Promising Strategy for Chemical Recycling of Carbon Fiber/Thermoset Composites: Self-Accelerating Decomposition in a Mild Oxidative System. Green Chem. 2012, 14, 3260–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitta, L.; Rizzo, G.; Tosto, C.; Cicala, G.; Blanco, I.; Pergolizzi, E.; Ciobanu, R.; Recca, G. Chemical Recycling of Fully Recyclable Bio-Epoxy Matrices and Reuse Strategies: A Cradle-to-Cradle Approach. Polymers 2023, 15, 2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Nutt, S. Chemical Treatment for Recycling of Amine/Epoxy Composites at Atmospheric Pressure. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2018, 153, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Hu, Y.; Yang, X.; Long, R.; Jin, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, W. Production and Closed-Loop Recycling of Biomass-Based Malleable Materials. Sci. China Mater. 2020, 63, 2071–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yan, S.; Zhao, J.; Liu, S.; Zhang, M.; Zheng, X.; Jia, L. Multiply Fully Recyclable Carbon Fibre Reinforced Heat-Resistant Covalent Thermosetting Advanced Composites. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, K.S.K.; Gao, W.J.; Chen, C.H.; Juang, T.Y.; Abu-Omar, M.M.; Lin, C.H. Degradation of Thermal-Mechanically Stable Epoxy Thermosets, Recycling of Carbon Fiber, and Reapplication of the Degraded Products. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 5304–5314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, W.; Braungart, M. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things, 1st ed.; Point, N., Ed.; North Point Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- den Braver-Sewradj, S.P.; van Spronsen, R.; Hessel, E.V.S. Substitution of Bisphenol A: A Review of the Carcinogenicity, Reproductive Toxicity, and Endocrine Disruption Potential of Alternative Substances. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2020, 50, 128–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fouyet, S.; Olivier, E.; Leproux, P.; Dutot, M.; Rat, P. Bisphenol A, Bisphenol F, and Bisphenol S: The Bad and the Ugly. Where Is the Good? Life 2021, 11, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapin, R.E.; Adams, J.; Boekelheide, K.; Gray, L.E.; Hayward, S.W.; Lees, P.S.J.; McIntyre, B.S.; Portier, K.M.; Schnorr, T.M.; Selevan, S.G.; et al. NTP-CERHR Expert Panel Report on the Reproductive and Developmental Toxicity of Bisphenol A. Birth Defects Res. B Dev. Reprod. Toxicol. 2008, 83, 157–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.G.; Chow, W.S.; Tan, S.G.; Chow, W.S. Biobased Epoxidized Vegetable Oils and Its Greener Epoxy Blends: A Review. Polym. Plast. Technol. Eng. 2017, 49, 1581–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jiang, Y.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, J. Bio-Based Epoxy Resin from Itaconic Acid and Its Thermosets Cured with Anhydride and Comonomers. Green Chem. 2013, 15, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llevot, A.; Grau, E.; Carlotti, S.; Grelier, S.; Cramail, H. From Lignin-Derived Aromatic Compounds to Novel Biobased Polymers. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2015, 37, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouf, C.; Nouailhas, H.; Fache, M.; Caillol, S.; Boutevin, B.; Fulcrand, H. Multi-Functionalization of Gallic Acid. Synthesis of a Novel Bio-Based Epoxy Resin. Eur. Polym. J. 2013, 49, 1185–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, W.; Xu, J.; Shang, S.; Song, Z. Synthesis and Characterization of Bio-Based Epoxy Thermosets Using Rosin-Based Epoxy Monomer. Iran. Polym. J. 2021, 30, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Yang, X.; Liu, H.; Shang, S.; Cai, Z.; Wu, K. Bio-Based Thermosetting Epoxy Foams from Epoxidized Soybean Oil and Rosin with Enhanced Properties. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 139, 111540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.K.; Khandelwal, V.; Manik, G. Development of Completely Bio-based Epoxy Networks Derived from Epoxidized Linseed and Castor Oil Cured with Citric Acid. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2018, 29, 2080–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Li, S.; Li, M.; Xia, J.; Zhou, Y. Epoxy Monomers Derived from Tung Oil Fatty Acids and Its Regulable Thermosets Cured in Two Synergistic Ways. Biomacromolecules 2014, 15, 837–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esposito Corcione, C.; Ferrari, F.; Striani, R.; Visconti, P.; Greco, A. Recycling of Organic Fraction of Municipal Solid Waste as an Innovative Precursor for the Production of Bio-Based Epoxy Monomers. Waste Manag. 2020, 109, 212–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, F.; Corcione, C.E.; Striani, R.; Saitta, L.; Cicala, G.; Greco, A. Fully Recyclable Bio-Based Epoxy Formulations Using Epoxidized Precursors Fromwaste Flour: Thermal and Mechanical Characterization. Polymers 2021, 13, 2768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitta, L.; Montalbano, G.; Corvaglia, I.; Brovarone, C.V.; Cicala, G. Printability of a Recycled Thermoplastic Obtained from a Chemical Recycling Process of a Fully-Recyclable Epoxy Matrix: An Upscaling Re-Use Strategy. Macromol. Symp. 2023, 411, 2200188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitta, L.; Pergolizzi, E.; Tosto, C.; Sergi, C.; Cicala, G. Fully-Recyclable Epoxy Fibres Reinforced Composites (FRCs) for Maritime Field: Chemical Recycling and Re-Use Routes. In Technology and Science for the Ships of the Future; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- La Rosa, A.D.; Greco, S.; Tosto, C.; Cicala, G. LCA and LCC of a Chemical Recycling Process of Waste CF-Thermoset Composites for the Production of Novel CF-Thermoplastic Composites. Open Loop and Closed Loop Scenarios. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 304, 127158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito Corcione, C.; Greco, A.; Visconti, P.; Striani, R.; Ferrari, F. Process for the Production of Bio-Resins and Bio-Resins thus Obtained. Patent IT 102019000016151, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mahlin, D.; Wood, J.; Hawkins, N.; Mahey, J.; Royall, P.G. A Novel Powder Sample Holder for the Determination of Glass Transition Temperatures by DMA. Int. J. Pharm. 2009, 371, 120–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbott, P. Principles and Applications of Thermal Analysis; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; ISBN 9781405131711. [Google Scholar]

- Di Mauro, C.; Malburet, S.; Graillot, A.; Mija, A. Recyclable, Repairable, and Reshapable (3R) Thermoset Materials with Shape Memory Properties from Bio-Based Epoxidized Vegetable Oils. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 8094–8104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia-Fernández, C.A.; Gómez-Barreiro, S.; López-Beceiro, J.; Tarrío Saavedra, J.; Naya, S.; Artiaga, R. Comparative Study of the Dynamic Glass Transition Temperature by DMA and TMDSC. Polym. Test. 2010, 29, 1002–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustata, F.; Tudorachi, N.; Bicu, I. The Kinetic Study and Thermal Characterization of Epoxy Resins Crosslinked with Amino Carboxylic Acids. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2015, 112, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample ID | PolarBear [%wt] | Epoxidized Waste Flour [%wt] | RecyclamineTM R*101 [phr] |

|---|---|---|---|

| EWF50_A15 | 50 | 50 | 15 |

| EWF100_A22 | 0 | 100 | 22 |

| Peak | Structure | Name |

|---|---|---|

| a |  | Oxazolidine, 3-methyl- |

| b |  | 1H-Pyrrole |

| c |  | 2-Methylperhydro-1,3-oxazine |

| d |  | 1H-Pyrazole |

| 1 |  | Phenol |

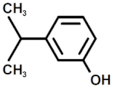

| 2 |  | Phenol, 3-(1-Methylethyl) |

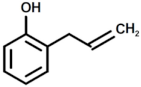

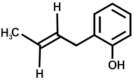

| 3 |  | Phenol, 2-(2-Propenyl) |

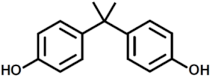

| 4 |  | Bisphenol A |

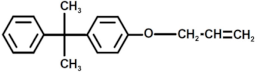

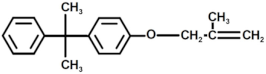

| 5 |  | Bisphenol A derivate 1 |

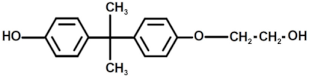

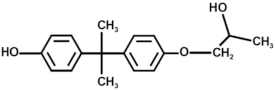

| 6 |  | 2-methyl phenol |

| 7 |  | 2-(But-2′-Enyl)Phenol |

| 8 |  | Bisphenol A derivate 2 |

| 9 |  | Bisphenol A derivate 3 |

| 10 |  | Bisphenol A derivate 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saitta, L.; Dattilo, S.; Rizzo, G.; Tosto, C.; Blanco, I.; Ferrari, F.; Carallo, G.A.; Cafaro, F.; Greco, A.; Cicala, G. Chemical Recycling of Bio-Based Epoxy Matrices Based on Precursors Derived from Waste Flour: Recycled Polymers Characterization. Polymers 2025, 17, 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17030335

Saitta L, Dattilo S, Rizzo G, Tosto C, Blanco I, Ferrari F, Carallo GA, Cafaro F, Greco A, Cicala G. Chemical Recycling of Bio-Based Epoxy Matrices Based on Precursors Derived from Waste Flour: Recycled Polymers Characterization. Polymers. 2025; 17(3):335. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17030335

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaitta, Lorena, Sandro Dattilo, Giuliana Rizzo, Claudio Tosto, Ignazio Blanco, Francesca Ferrari, Gloria Anna Carallo, Fabrizio Cafaro, Antonio Greco, and Gianluca Cicala. 2025. "Chemical Recycling of Bio-Based Epoxy Matrices Based on Precursors Derived from Waste Flour: Recycled Polymers Characterization" Polymers 17, no. 3: 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17030335

APA StyleSaitta, L., Dattilo, S., Rizzo, G., Tosto, C., Blanco, I., Ferrari, F., Carallo, G. A., Cafaro, F., Greco, A., & Cicala, G. (2025). Chemical Recycling of Bio-Based Epoxy Matrices Based on Precursors Derived from Waste Flour: Recycled Polymers Characterization. Polymers, 17(3), 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym17030335