Comparative Analysis of Soil Fertility, Productivity, and Sustainability of Organic Farming in Central Europe—Part 2: Cultivation Systems with Different Intensities of Fertilization and Legume N2 Fixation as well as Perspectives for Future Development

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Description of Long-Term Field Trials Involved

3. Farm Surveys of Agricultural Practice

4. Methods of Soil and Plant Examination

- -

- Nmin (kg N ha−1) as NH4- and NO3-nitrogen (N) in 0.0125 molar calcium chloride (CaCl2) solution at 0–90 cm soil depth or depth drilling at 90–200 cm with ram core probes (6 cm diameter) [55];

- -

- Smin as soluble sulfur (S) (kg S ha−1) at 0–90 cm soil depth, according to [56];

- -

- pH value at 0–30 cm depth in 0.01 molar calcium chloride solution (CaCl2) [57];

- -

- -

- CaCl2-available magnesium (Mg) (mg 100 g−1) at 0–30 cm depth [60];

- -

- total organic carbon (Corg in % DM) at 0–30 cm depth with elemental analysis (DIN ISO 10694);

- -

- total N (Nt in % DM) at 0–30 cm depth, according to [56].

5. Biometric Evaluation

6. Results of Increasing Intensities of Fertilization and Leguminous N2 Fixation

6.1. Influence of Average Intensities of Fertilization and Crop Rotation Shares of Legumes as a Basis for Comparison

6.2. Influence of Low Intensities of Fertilization and without Livestock Farming

Crop Rotations with 33% Forage Legumes

- -

- Loamy soils: +0.031% Corg, −0.008% Nt, −1.24 mg P 100 g−1, −3.67 mg K 100 g−1 soil;

- -

- Sandy soils: +0.008% Corg, −0.009% Nt, −2.55 mg P 100 g−1, −2.35 mg K 100 g−1 soil.

6.3. Market Crop Cultivation with Low Legumes Predominantly as Grain Legumes in Crop Rotations

6.3.1. Effects of 33% Legumes

- -

- Decrease in average yield level with partial replacement to 87% and with complete replacement by grain legumes to an average of 74%.

- -

- The N2 fixation of legumes drops only slightly by up to 10%.

- -

- The gross N balances decrease from approx. +48 kg N ha−1 (=100%) with 33% clover-grass cultivation to +45 kg to +22 kg N ha−1 with 33% grain legumes.

- -

- The increased removal of P-rich grain products and the reduction in K-rich clover-grass cultivation leads to a further strengthening of the negative P balances on one side and to an improvement of the negative K balances on the other side.

- -

- The stepwise reduced supply of crop and root residues due to the replacement of clover-grass by grain legumes causes an increasing reduction in the Corg contents of the soil, which can also be confirmed by humus balancing.

- -

- The extent of the soil Corg change until equilibrium is reached would be approximately as follows: variant 1 +0.124% Corg, variant 2 −0.090% Corg, and variant 3 −0.155% Corg.

- -

- Since there are clearly lower Nmin values under the clover-grass cultivation, a slight increase in the mean Nmin contents in the spring occurs due to the cultivation of grain legumes, but the Nmin values of the first and second after-crops are at the same high level or, after clover-grass mulch, at a slightly higher level.

- -

- The values of the crude protein contents or the sedimentation values of wheat also decrease by 10–15%, with the probability of achieving a sufficiently high baking quality being reduced (not included in Table 5).

6.3.2. Effect of 20% Legumes

- -

- Variant 2 with clover-grass cultivation and organic fertilization by 30–40 kg N ha−1 year−1: yields −15%, N2 fixation −27%, N balance −44%, Corg content −2%, slightly positive humus balance.

- -

- Variant 3 with grain legume cultivation and similar high fertilization: yields −26%, N2 fixation ±0%, N balance −56%, Corg content −4%, still slightly positive humus balance.

- -

- Variant 4 with grain legume cultivation without organic fertilization: yields −31%, N2 fixation ±0%, N balance −16 kg ha−1, Corg content −10%, negative humus balance.

- -

- Legume portions and composition: 12 (0–19)% clover-grass, 9 (0–25)% grain legumes, 21 (10–27)% proportions per crop rotation;

- -

- legume N2 fixation: 31 (4–48) kg N ha−1 year−1;

- -

- animal husbandry: 0.08 (0–0.8) LU ha−1;

- -

- organic fertilization: 8 (0–50) kg N ha−1 year−1;

- -

- Gross N balance: +7 (−22 to +33) kg N ha−1 year−1;

- -

- humus balance: −63 (−250 to +187) HEQ ha−1 year−1.

6.4. Effect of High to Very High Intensities with 33% Legume Cultivation in the Crop Rotations

6.4.1. Effects of Intensities around 1.0 LU ha−1

- -

- N supply from organic manures: 65 kg N ha−1 (=245%);

- -

- legume N2 fixation: 70 kg N ha−1 (=139%);

- -

- N removal through crop yields: 121 kg N ha−1 (=136%);

- -

- N balance: 58 kg N ha−1 (=180%);

- -

- P balance: −3.2 kg P ha−1;

- -

- K balance: −38 kg K ha−1.

- -

- Loamy soils: +0.077% Corg, −0.004% Nt, −0.26 mg P 100 g−1, −1.30 mg K 100 g−1 soil;

- -

- sandy soils: +0.040% Corg, −0.004% Nt, −1.13 mg P 100 g−1, +0.29 mg K 100 g−1 soil.

6.4.2. Effects of High Intensities around 2.0 LU ha−1

- -

- Loamy soils: +0.108% Corg, +0.002% Nt, +0.84 mg P 100 g−1, +1.74 mg K 100 g−1 soil;

- -

- sandy soils: +0.058% Corg, ±0.000% Nt, +0.45 mg P 100 g−1, +2.36 mg K 100 g−1 soil.

6.5. Systems with 50% Legume Cultivation and Very High Organic Fertilization

- -

- Although the legume share in the crop rotation increases by approx. 17% between variants 1–3, only an additional legume N2 fixation of approx. 5–20 kg N ha−1 is still achieved.

- -

- The increased legume cultivation can therefore only save a small amount of organic N fertilization between 0–40 kg ha−1, so that between variant 1 and around variants 3–4, an equal level of yields in the crop species and in the soil supply is ensured.

- -

- A legume share of 46% in the crop rotation is still not sufficient in variant 2 with additional leaving of the by-products and mulching of the clover-grass growth on the plots to achieve a level of congruence with variant 1 in many characteristics.

- -

- Between variant 1 and 2, the proportion of deep-rooted clover-grass has been reduced by 5%, the balances are 12 kg N ha−1 higher, with decreasing Nmin values up to 90 cm depth, the N transfer potential between 0.90–2.50 m depth has been increased by 12 kg, and up to 4.00 m soil depth in variant 2 by 9 kg N ha−1.

- -

- With increasing organic fertilization, the legume share in the clover-grass mixture obviously drops from 58% without fertilization (variant 3) to 49% with 2.7 LU ha−1 organic fertilization (variant 6) more clearly than at the level of 33% legume cultivation in the crop rotation.

- -

- The legume N2 fixation increases by 32% overall up to the 1.3 LU ha−1 organic fertilization stage (variant 1 compared to variant 5) and then drops again by about 4% at the very high fertilization of variant 6.

- -

- At the stage of 50% legumes in the crop rotation, the N2 fixation level increases by only 15% due to organic fertilization (variant 3 compared to variant 5).

- -

- The yield increase in all crops with increasing fertilization clearly follows the law of diminishing yield growth and already reaches a maximum at the level of 1.3 LU ha−1 (cf. variant 1 and variant 5: +15% yield increase); only for potatoes is an additional rise of +17% in tuber yield achieved, up to 2.7 LU ha−1 (variant 6, not shown).

- -

- While at a legume level of 33% a yield increase of approx.. 20% can still be achieved up to the 2.7 LU ha−1 stage; with high legume cultivation an increase in yield of only 17% up to the 1.3 LU ha−1 stage occurs due to increasing fertilization, and with further doubling of fertilization already drops again by 4%.

- -

- Although the crop yield has been significantly increased as a result of fertilization, the N balances have risen considerably more in line with the fertilization level; from variant 5 and especially from variant 6, it can no longer be assumed that a well-managed agricultural land use is taking place, even if the Nt reserves in the soil are taken into account, as the balances rise to values of over 150 kg N ha−1.

- -

- Nmin amounts in the spring also increased over-proportionally between variants 1 and 6 by up to 32% reaching 90 kg N ha−1.

- -

- Due to the higher N availability, the contents of crude protein of winter wheat have also increased by relatively 12% to over 12.1% crude protein in the DM of the grains.

- -

- The Corg contents in the soil have increased very strongly in the topsoil as a result of the organic fertilization; a further aspect to consider is the still relatively short period of 12 years that has been taken into account.

- -

- The calculated humus balances have developed largely parallel to the Corg levels as a result of increasing fertilization, but cultivation methods of variants 1 and 3 mark a lower end (supply grade B), and for variant 6, the upper end, of well-managed cultivation (grade D).

- -

- The P and K balances have also changed as a result of increasing fertilization, although at the same fertilization level (variant 1 compared to variant 4) there has been hardly any change in the often clearly negative balances as a result of the increased proportion of legumes (P: −6 to −14 kg ha−1; K: −57 to −76 kg ha−1 year−1), while after high fertilization in variant 6 there have been equally clear positive balances with +10 kg P ha−1 and +52 kg K ha−1.

- -

- Variant 3: +0.094% Corg, ±0.000% Nt, −0.29 mg P 100 g−1, +0.29 mg K 100 g−1 soil.

- -

- Variant 4: +0.109% Corg, +0.001% Nt, −0.05 mg P 100 g−1, +0.74 mg K 100 g−1 soil.

- -

- Variant 5: +0.127% Corg, +0.002% Nt, +0.30 mg P 100 g−1, +1.53 mg K 100 g−1 soil.

- -

- Variant 6: +0.157% Corg, +0.005% Nt, +1.00 mg P 100 g−1, +3.11 mg K 100 g−1 soil.

- -

- N supply of organic fertilizer: 112 kg N ha−1 (=267%);

- -

- legume share in the crop rotation: 48% (=146%);

- -

- legume N2 fixation: 96 kg N ha−1 (=185%);

- -

- humus balance: ~564 kg HEQ ha−1 (approx. 397%, supply grade E);

- -

- N balance: 80 kg N ha−1 (=296%);

- -

- P balance: +7 kg P ha−1;

- -

- K balance: +35 kg K ha−1.

7. Summary Effects of Fertilization Intensity Using Nitrogen as an Example

7.1. Long-Term Influence of Fertilization on N2 Fixation and Legume Proportions in Clover-Grass

| Intensity Level: | 0.0 LU ha−1 | 0.5 LU ha−1 | 1.0 LU ha−1 | 2.0 LU ha−1 |

| 100 (64.9) | 104 | 97 | 88 |

| 100 (123) | 98 | 95 | 94 |

| 100 (84.4) | 88 | 85 | 81. |

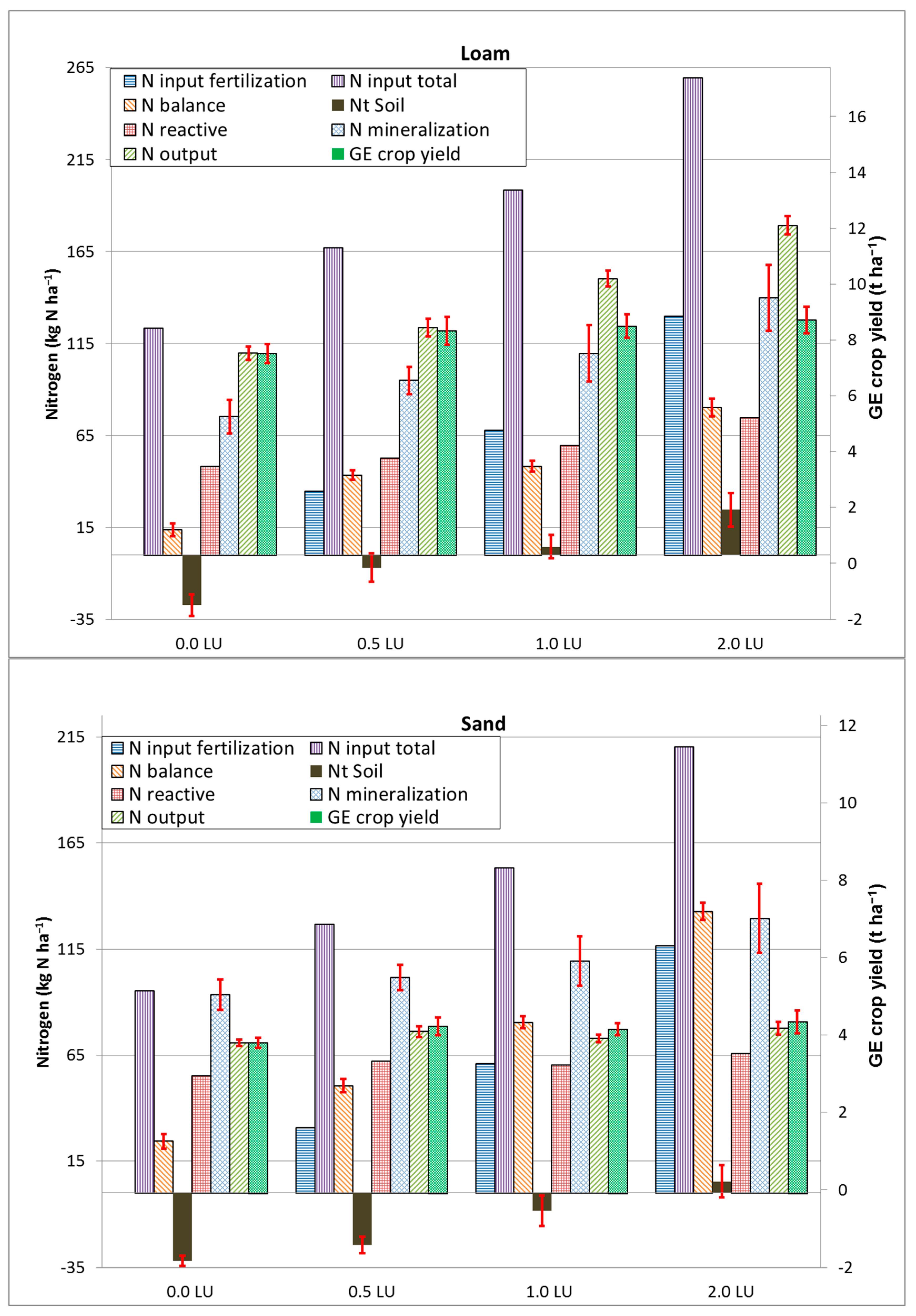

7.2. Relationships between Components of N Balancing and GE-Yields on Sites with Light and Heavy Soils

- -

- Balance criteria (input, output, balance);

- -

- the sum of reactive N (=Nmin quantities after harvest up to 0.90 m + 0.90–2.00 m in the depth profile + calculated N leaching quantity);

- -

- the calculated N mineralization;

- -

- a relative comparison between the amount of N removed with the harvests and the GE-yield.

8. Validity of Relations between Nutrient Balances and Development of Soil Fertility Characteristics

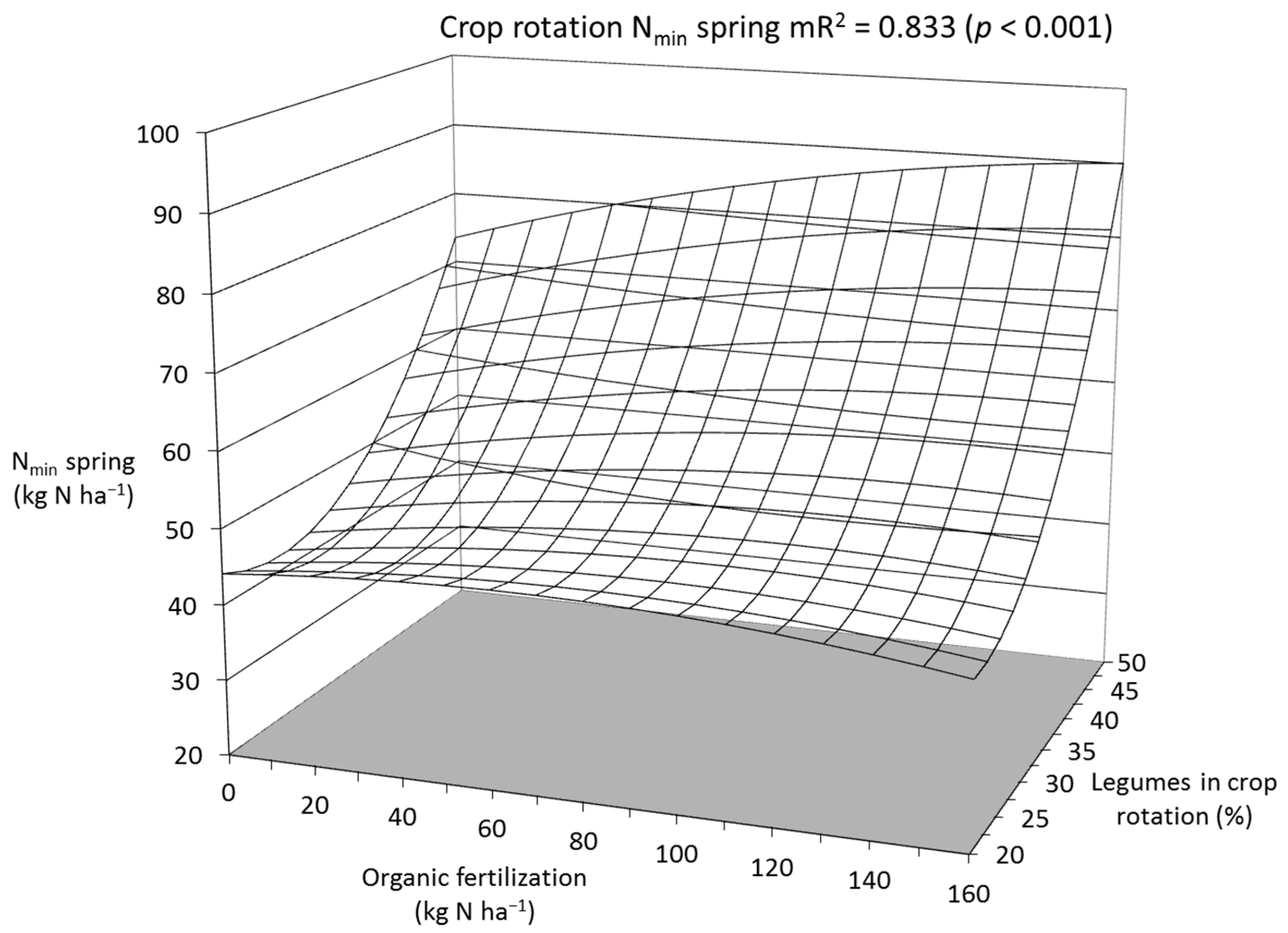

9. Quantitative Relation between Intensity of Organic Fertilization and Legume Cultivation, Using the Example of Heavy Soils (Loam)

- -

- y = −985.91 + 4.48035x1 − 0.00924x12 + 56.69970x2 − 0.65578x22 − 0.01492x1x2.

- -

- y = −582.85 + 8.69935x1 − 0.00356x12 + 19.36387x2 + 0.00102x22 − 0.14583x1x2.

- -

- y = 43.84 + 1.09191x1 − 0.000893x12 − 4.78565x2 + 0.07597x22 − 0.01659x1x2.

- -

- y = −101.35 − 0.03893x1 − 0.00153x12 + 8.22668x2 − 0.08806x22 + 0.00720x1x2.

- -

- y = 80.68 − 0.02214x1 − 0.000454x12 − 2.94914x2 − 0.05613x22 + 0.00396x1x2.

- -

- y = 3.34 + 0.39234x1 − 0.00153x12 + 2.78015x2 − 0.02438x22 − 0.00192x1x2.

- -

- y = −132.88 + 0.29868x1 + 0.00165x12 + 7.81346x2 − 0.09995x22 + 0.00768x1x2.

- -

- y1 = −26.67 + 0.29259x1 + 0.000411x12 + 0.45648x2 − 0.00393x22 − 0.00414x1x2;

- -

- y2 = −251.61 + 0.51302x1 + 0.00369x12 + 9.30328x2 − 0.11358x22 − 0.00607x1x2.

- -

- Ordinary gross balancing including N deposition and determination of N balances and (apparent) N efficiencies (N efficiency trials; N efficiency farms).

- -

- Ordinary gross balancing with additional accounting of negative soil Nt balances in nutrient inputs and positive balances in outputs and determination of total balances and total efficiency (total N efficiency trials).

- -

- y = 209.81 + 0.57091x1 − 0.000913x12 − 8.42298x2 + 0.11956x22 − 0.01323x1x2.

10. Discussion and Conclusions

- -

- Cultivation of mixed crops;

- -

- cultivation of second crops;

- -

- better use of breeding progress;

- -

- cultivation and crop rotation optimization depending on the intensity level of the farm;

- -

- reduction in application losses during the storage and application of fertilizers;

- -

- use of fertilizers with low contents of readily available and reactive nutrient components;

- -

- prevention of yield losses caused by the minimum law for nutrients, pH value, organic matter, water supply, etc.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Regulation (EU) 2018/848 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 on organic production and labelling of organic products and repealing Council Regulation (EC) No 834/2007. Off. J. Europ. Union 2018, L150, 1–92.

- Organic Farming Statistics. Eurostat Statistics Explained. 2021. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Organic_farming_statistics#Organic_production (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Haas, G.; Deittert, C.; Köpke, U. Farm-gate nutrient balance assessment of organic dairy farms at different intensity levels in Germany. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2007, 22, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelm, M.; Hüwing, H.; Kemper, N. COMPASS Vergleichende Analyse der Pflanzlichen Produktion auf Ökologischen und Konventionellen Praxisbetrieben in Schleswig-Holstein; Endbericht; Christian-Albrechts-Universität: Kiel, Germany, 2007; Available online: https://www.grassland-organicfarming.uni-kiel.de/de/pdf/COMPASS%20Endbericht.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Kelm, M.; Loges, R.; Taube, F. N-Auswaschung unter ökologisch und konventionell bewirtschafteten Praxisflächen in Norddeutschland–Ergebnisse aus dem Projekt COMPASS. Beitr. Wiss. Tag. Ökol. Landbau Hohenh. 2007, 9, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hülsbergen, K.-J.; Rahmann, G. Klimawirkungen und Nachhaltigkeit Ökologischer und Konventioneller Betriebssysteme–Untersuchungen in Einem Netzwerk von Pilotbetrieben; Abschlussbericht Förderkennzeichen 06OE160 (TUM) und 06OE353 (TI); Thünen Report 8; Johann Heinrich v. Thünen-Institut: Braunschweig, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Möller, K. Nährstoffstatus und Nährstoffbilanzen im Ökologischen Gemüsebau. In KTBL-Fachgespräch Organische Handelsdünger im Ökologischen Landbau, Stand des Wissens und Forschungsbedarf; Bioland Treffpunkt: Fulda, Germany, 2014; Available online: https://www.ktbl.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Allgemeines/Download/Handelsduenger/Naehrstoffstatus-Naehrstoffbilanzen.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Cooper, J.; Reed, E.Y.; Hörtenhuber, S.; Lindenthal, T.; Loes, A.-K.; Mäder, P.; Magid, J.; Oberson, A.; Kolbe, H.; Möller, K. Phosphorus availability on many organically managed farms in Europe. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2018, 110, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmelikova, L.; Schmid, H.; Anke, S.; Hülsbergen, K.-J. Nitrogen-use efficiency of organic and conventional arable and dairy farming systems in Germany. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2021, 119, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbe, H.; Meyer, D.; Schmidtke, K. Schlaggenaue Analyse von 32 Betrieben des ökologischen Landbaus im Freistaat Sachsen: Fruchtfolgegestaltung. Ber. Landwirtsch. 2021, 99 (Suppl. S1), 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, H.; Meyer, D. Schlaggenaue Analyse von 32 Betrieben des ökologischen Landbaus im Freistaat Sachsen: Nährstoff- und Humusmanagement. Ber. Landwirtsch 2021, 99 (Suppl. S2), 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Böhm, H.; Buchecker, K.; Dresow, J.; Dreyer, W.; Landzettel, C.; Mahnke-Plesker, S.; Westhues, F. Optimierung der ökologischen Kartoffelproduktion; Landbauforschung Sonderheft 348. Johann Heinrich von Thünen-Institut (vTI), Institut für Ökologischen Landbau: Westerau, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Seufert, V.; Ramankutty, N.; Foley, J.A. Comparing the yield of organic and conventional agriculture. Nature 2012, 485, 229–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recknagel, J.; Nußbauer, H. Ertragsentwicklung langjährig viehlos bewirtschafteter Öko-Ackerflächen am Oberrhein. Beitr. Wiss.-Tagung Ökol. Landbau Freising-Weihenstephan 2017, 14, 330–331. Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/31552/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Zikeli, S.; Deil, L.; Möller, K. Nährstoffmanagement in ökologisch bewirtschafteten Gewächshäusern in Südwest-Deutschland: Bedingt der Anbauverband die Düngestrategie? Beitr. Wiss.-Tagung Ökol. Landbau Eberswalde 2015, 13, 280–283. Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/27137/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Urbatzka, P.; Cais, K.; Rehm, A.; Rippel, R. Status-Quo-Analyse von Dauerversuchen: Bestimmung des Forschungsbedarfes für den ökologischen Landbau; Bayer. Landesanstalt für Landwirtschaft, Institut Agrarökologie, Ökologischen Landbau Bodenschutz: Freising, Germany, 2011; Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/19317/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Mayer, J.; Mäder, P. Langzeitversuche–Eine Analyse der Ertragsentwicklung. In Ökologischer Landbau–Grundlagen, Wissensstand und Herausforderungen; Freyer, B., Ed.; UTB: Stuttgart, Germany, 2016; pp. 421–445. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, H. Wie ist es um die Bodenfruchtbarkeit im Ökolandbau bestellt: Nährstoffversorgung und Humusstatus. In Bodenfruchtbarkeit–Grundlage erfolgreicher Landwirtschaft, Proceedings of the Tagung d. Verbandes d. Landwirtschaftskammern (VLK) Bundesarbeitskreises Düngung (BAD) in Würzburg; Bundesarbeitskreis Düngung: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2015; pp. 89–123. Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/29539/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Kolbe, H. Comparative Analysis of Soil Fertility, Productivity, and Sustainability of Organic Farming in Central Europe−Part 1: Effect of Medium Manifestations on Conversion, Fertilizer Types and Cropping Systems. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, G.; Deittert, C. Stoffflussanalyse und Produktionseffizienz der Milchviehhaltung Unterschiedlich Intensiver ökologisch Wirtschaftender Betriebe; Forschungsbericht FKZ 020E462; Institut für Organischen Landbau: Bonn, Germany, 2004; Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/5163/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Damhofer, I.; Lindenthal, T.; Zollitsch, W.; Bartel-Kratochvil, R. Konventionalisierung: Notwendigkeit einer Bewertung mittels Indikatorsystem, basierend auf den IFOAM-Prinzipien. Beitr. Wiss. Tag. Ökol. Landbau Zürich 2009, 10, 514–517. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, H. Untersuchungen zur Steigerung der Produktionsintensität im ökologischen Landbau am Beispiel des Lehr- und Versuchsbetriebes Gladbacherhof; Giessener Schriften Ökologischen Landbau 3; Dr. Köster Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Niggli, U. Ökolandbau: Alle Zeichen stehen auf Intensivierung. Mit mehr Forschung ist reichlich Potenzial zu heben. Lebendige Erde 2013, 5, 1. Available online: http://www.lebendigeerde.de/index.php?id=hintergrund_135 (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Kühling, I.; Hess, J.; Trautz, D. Nachhaltige Intensivierung und Ökolandbau–passt das zusammen? Ökol. Landbau 2015, 3, 18–20. [Google Scholar]

- Sommer, H.; Krutzinna, C.; Keil, J.; Heß, J. Intensivierung einer Fruchtfolge unter ökologischen Bewirtschaftungsbedingungen–Bewertung der Auswirkungen auf die Nachhaltigkeit. Beitr. Wiss.-Tagung Ökol. Landbau Eberswalde 2015, 13, 1–4. Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/27159/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Freyer, B. Ernährungssicherung. In Ökologischer Landbau–Grundlagen, Wissensstand und Herausforderungen; Freyer, B., Ed.; UTB-Verlagsgruppe, Haupt Verlag: Bern, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 183–191. [Google Scholar]

- Freyer, B.; Klimek, M.; Fiala, V. Ethik im Ökologischen Landbau–Grundlagen und Diskurs. In Ökologischer Landbau–Grundlagen, Wissensstand und Herausforderungen; Freyer, B., Ed.; UTB-Verlagsgruppe, Haupt Verlag: Bern, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 44–79. [Google Scholar]

- Köpke, U. Ressourcenschutz und ökologische Leistungen. In Ökologischer Landbau–Grundlagen, Wissensstand und Herausforderungen; Freyer, B., Ed.; UTB-Verlagsgruppe, Haupt Verlag: Bern, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 590–612. [Google Scholar]

- Blumenstein, B. Sustainable Intensification of Organic and Low-Input Agriculture through Integrated Bioenergy Production; Kassel University Press: Kassel, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, A.; Schader, C.; El-Hage Scialabba, N.; Brüggemann, J.; Isensee, A.; Erb, K.-H.; Smith, P.; Klocke, P.; Leiber, F.; Stolze, M.; et al. Strategies for feeding the world more sustainably with organic agriculture. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1–13. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-017-01410-w.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- Haller, L.; Moakes, S.; Niggli, U.; Riedel, J.; Stolze, M.; Thompson, M. Entwicklungsperspektiven der ökologischen Landwirtschaft in Deutschland; Texte 32; Umweltbundesamt: Dessau-Roßlau, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rempelos, L.; Baranski, M.; Wang, J.; Adams, T.N.; Adebusuyi, K.; Beckman, J.J.; Brockbank, C.J.; Douglas, B.S.; Feng, T.; Greenway, J.D.; et al. Integrated soil and crop management in organic agriculture: A logical framework to ensure food quality and human health? Agronomy 2021, 11, 2494. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11122494 (accessed on 19 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- Hof-Kautz, C. Wie Entwickeln Sich Langjährige Viehlose Fruchtfolgen Unter den Bedingungen des Ökologischen Landbaus? Landwirtschaftskammer (LWK) Nordrhein-Westfalen: Köln-Auweiler, Germany, 2019; written communication. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, W. Grundbodenbearbeitung, Fruchtfolgegestaltung und Düngung im ökologischen viehlosen Ackerbau der Magdeburger Börde. In Jahrestagung Ökologischer Landbau 5; Landesanstalt Landwirtsch., Forsten Gartenb.: Bernburg-Strenzfeld, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, W. Ertragstrends in modellhaften Fruchtfolgen im mitteldeutschen Trockengebiet–Ergebnisse aus dem Versuch Leistungsfähigkeit verschiedener Landbausysteme am Standort Bernburg. In Internat. Arbeitsgemein. Bodenfruchtbarkeit; written communication; LTFE-Meeting: Gießen, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Koch, W. Versuch Anbausysteme-Vergleich Bernburg. In DLG-Anbausysteme-Vergleich; written communication; Agritechnica: Hannover, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, R.; Salzeder, G.; Schmidt, M.; Wiesinger, K.; Urbatzka, P. Einfluss verschiedener Fruchtfolgen viehhaltender und viehloser Systeme auf Ertrag und Produktivität: Ergebnisse eines Dauerfeldversuches. Beitr. Wiss. Tag. Ökol. Landbau Bonn 2013, 12, 54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Castell, A.; Eckl, T.; Schmidt, M.; Beck, R.; Heiles, E.; Salzeder, G.; Urbatzka, P. Fruchtfolgen im Ökologischen Landbau–Pflanzenbaulicher Systemvergleich in Viehhausen und Puch. Zwischenbericht 2005–2013; Schriftenr. Bayer. Landesanstalt Landwirtsch. 9; Freising-Weihenstephan, Germany. 2016. Available online: https://www.lfl.bayern.de/mam/cms07/publikationen/daten/schriftenreihe/fruchtfolgen-oekologischer-landbau_pflanzenbaulicher-systemvergleich_lfl-schriftenreihe.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Schulz, F. Vergleich Ökologischer Betriebssysteme mit und ohne Viehhaltung bei Unterschiedlicher Intensität der Grundbodenbearbeitung. Effekte auf Flächenproduktivität, Nachhaltigkeit und Umweltverträglichkeit. Ph.D. Thesis, University, Gießen, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, H. Berichte aus dem Ökolandbau 2022–Möglichkeiten und Grenzen der Intensivierung. Zusammenführung der Ergebnisse von komplexen Dauersystemversuchen zur Untersuchung ökologischer Anbau- und Düngungsverfahren in zwei Anbausystemen (Marktfrucht und Futterbau) auf Ertrag, Produktqualität, Bodenfruchtbarkeit und Umweltwirkungen auf einem Sand- und Lößboden in Sachsen; Dr. H. Kolbe: Schkeuditz, Germany, 2022; pp. 1–444. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:bsz:14-qucosa2-784857 (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Meyer, D.; Kolbe, H.; Schuster, M. Berichte aus dem Ökolandbau 2021–Das Ökofeld Roda. Ergebnisse zur langjährigen Bewirtschaftung von Feldversuchsflächen der Versuchsstation Roda in Sachsen; Dr. H. Kolbe: Schkeuditz, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–139. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:bsz:14-qucosa2-766432 (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Farack, K.; Müller, P.; Schliephake, W.; Kolbe, H. Berichte aus dem Ökolandbau 2021–Dauerversuch zur organischen und mineralischen Grunddüngung. Einfluss steigender organischer sowie mineralischer P- und K-Düngung auf Merkmale der Bodenfruchtbarkeit, Ertrag und Qualität der Fruchtarten in einem ökologischen Dauerversuch auf Lehmboden; Dr. H. Kolbe: Schkeuditz, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–112. Available online: https://slub.qucosa.de/api/qucosa%3A76876/attachment/ATT-0/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Meyer, D.; Schmidtke, K.; Wunderlich, B.; Lauter, J.; Wendrock, Y.; Grandner, N.; Kolbe, H. Berichte aus dem Ökolandbau 2021–Nährstoffmanagement und Fruchtfolgegestaltung in sächsischen Ökobetrieben. Analyse des Nährstoff- und Humusmanagements sowie der Fruchtfolgegestaltung in 32 Betrieben des ökologischen Landbaus im Freistaat Sachsen; Dr. H. Kolbe: Schkeuditz, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–104. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:bsz:14-qucosa2-769182 (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Reimer, M.; Hartmann, T.E.; Oelofse, M.; Magid, J.; Bünemann, E.K.; Möller, K. Reliance on biological nitrogen fixation depletes soil phosphorus and potassium reserves. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2020, 118, 273–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisen, E. Hoftor-Bilanz von Phosphor- und Kalium in Öko-Milchviehbetrieben. Beitr. Wiss. Tag. Ökol. Landbau Freis. Weihensteph. 2017, 14, 376–377. Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/31553/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Kolbe, H. Nährstoff- und Humusversorgung im Ökolandbau. Über die unterschiedlichen Entwicklungstendenzen bei der Bodenfruchtbarkeit. In Der kritische Agrarbericht 2016; AgrarBündnis, Konstanz; ABL Bauernblatt Verlag: Hamm, Germany, 2016; pp. 168–173. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, C.; Oltmanns, M.; Spiegel, A.-K. Humusmanagement und Humusbilanz hessischer Öko-Betriebe; Broschüre; Landesbetrieb Landwirtschaft Hessen (LLH): Kassel, Germany, 2013; Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/22605/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Hülsbergen, K.-J.; Schmid, H. Treibhausgasemissionen ökologischer und konventioneller Betriebssysteme. Emissionen landwirtschaftlich genutzter Böden. KTBL Schrift 2010, 483, 229–483. [Google Scholar]

- Quirin, M.; Emmerling, C.; Schröder, D. Phosphorgehalte und -bilanzen konventionell, integriert und biologisch bewirtschafteter Acker- und Grünlandflächen und Maßnahmen zum Phosphorabbau hoch versorgter Flächen. Pflanzenbauwiss 2006, 10, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- Gutser, R.; Reents, H.J.; Rühling, I.; Schmid, H.; Weinfurtner, K.H. Flächen- und betriebsbezogene Indikatoren auf der Grundlage des Langzeitmonitorings. In Forschungsverbund Agrarökosysteme München Jahresbericht: 2002; Forschungsverbund Agrarökosysteme München: München, Germany, 2002; pp. 147–159. Available online: https://mediatum.ub.tum.de/doc/1304992/document.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Friedel, J.; Kasper, M.; Schmid, H.; Hülsbergen, K.-J.; Freyer, B. Need for phosphorus input in Austrian organic farming? Proc. ISOFAR Sci. Conf. Istanb. Turk. 2014, 4, 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, P.M.; Stockdale, E.A.; Sylvester-Bradley, R.; Philipps, L.; Smith, K.A.; Lord, E.I.; Watson, C.A.; Fortune, S. N, P and K budgets for crop rotations on nine organic farms in the UK. Soil Use Manag. 2003, 19, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetter, R.; Miersch, M.; Weissbart, J.; Freyer, B.; Rennenkampff, K. Stickstoffversorgung und -Dynamik in Fruchtfolgen Vieharmer Betriebe des Ökologischen Landbaus; Abschlussbericht; ITADA-Sekretatiat: Colmar, France, 2000; Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/2439/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Asdal, A.; Bakken, A.K. Nutrient balances and yields during conversion to organic farming in two crop rotation systems. In Designing and Testing Crop Rotations for Organic Farming: Proceedings from an International Workshop; Olesen, J.E., Eltun, R., Gooding, M.J., Jensen, E.S., Köpke, U., Eds.; Danish Research Centre for Organic Farming (DARCOF): Tjele, Denmark, 1999; pp. 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Wehrmann, J.; Scharpf, H.C. Der Mineralstickstoffgehalt des Bodens als Maßstab für den Stickstoffdüngebedarf (Nmin-Methode). Plant Soil 1979, 52, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, G. Die Untersuchung der Böden. In VDLUFA-Methodenbuch 1; VDLUFA-Verlag: Darmstadt, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Kerschberger, M.; Deller, B.; Hege, U.; Heyn, J.; Kape, H.-E.; Krause, O.; Pollehn, J.; Rex, M.J.; Severin, K. Bestimmung des Kalkbedarfs von Acker- und Grünlandböden; Standpunkt; VDLUFA: Darmstadt, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Egner, H.; Riehm, H. Die Doppellactatmethode, zit; Methodenbuch, I., von Thun, R., Hermann, R., Knickmann, E., Eds.; Neumann-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Schüller, H. Die CAL-Methode, eine neue Methode zur Bestimmung des pflanzenverfügbaren Phosphates in Böden. Z. Pflanzenern. Bodenkde. 1969, 123, 48–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachtschabel, P. Die Magnesiumversorgung nordwestdeutscher Böden und seine Beziehungen zum Auftreten von Mangelsymptomen an Kartoffeln. Z. Pflanzenern. Bodenkde. 1956, 74, 202–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasper, M.; Freyer, B.; Amon, B.; Hülsbergen, K.-J.; Schmid, H.; Friedel, J.K. Modellberechnungen für treibhausgasrelevante Emissionen und Senken in landwirtschaftlichen Betrieben Ost-Österreichs. Beitr. Wiss. Tag. Ökol. Landbau Gießen 2011, 11, 177–180. [Google Scholar]

- DOK Versuch. Schweiz; Landwirtschaftl. Forsch., Sonderausgabe 1995; Eidgenöss. Forschungsanstalt Agrikulturchemie Umwelthygiene (FAC): Liebefeld, Switzerland, 1995.

- Mäder, P.; Fliessbach, A.; Dubois, D.; Gunst, L.; Fried, P.; Niggli, U. Soil fertility and biodiversity in organic farming. Science 2002, 296, 1694–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehl, F.; Oberson, A.; Tagmann, H.U.; Besson, J.M.; Dubois, D.; Mäder, P.; Roth, H.-R.; Frossard, E. Phosphorus budget and phosphorus availability in soils under organic and conventional farming. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2002, 62, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, J.; Dittmann, B. Nährstoffbilanzen im ökologischen Landbau unter Berücksichtigung unterschiedlicher Bewirtschaftungssysteme. In VDLUFA-Schriftenreihe; Kongressband: Bonn, Germany, 2004; Volume 59, pp. 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer, J.; Dittmann, B. Nährstoffbilanzen im Ökologischen Landbau Unter Berücksichtigung Unterschiedlicher Bewirtschaftungssysteme; LVL Brandenburg: Güterfelde, Germany. Available online: https://gruendungsnetz.brandenburg.de/sixcms/media.php/4055/N%C3%A4hrstoffbilanzen%20im%20%C3%B6kologischen%20Landbau.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Köpke, U.; Dahn, C.; Täufer, F.; Zaller, J. Soil fertility properties in a long-term field experiment with organic and biodynamic farmyard manure amendment. In Long Term Field Experiments in Organic Farming; Raupp, J., Pekrun, C., Oltmanns, M., Köpke, U., Eds.; ISOFAR Scientific Series 1; Verlag Dr. Köster: Berlin, Germany, 2006; pp. 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, H.; Thamm, U. Standortspezifische Auswirkungen Einer Langjährigen Ökologischen Bewirtschaftung auf Acker- und Pflanzenbauliche Sowie Umweltrelevante Parameter; Forschungsbericht 22/04; Landesforschungsanstalt für Landwirtschaft Fischerei: Gülzow, Germany, 2005; Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/9346/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Kolbe, H. Zusammenführende Untersuchungen zur Genauigkeit und Anwendung von Methoden der Humusbilanzierung im konventionellen und ökologischen Landbau. In Bilanzierungsmethoden und Versorgungsniveau für Humus; Schriftenr; Landesamt für Umwelt, Landwirtschaft und Geologie (LfULG): Dresden, Germany, 2012; Volume H19, pp. 4–85. Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/20826/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Alvermann, G. Muss ich dem Boden etwas zurückgeben. Bioland 1990, 5, 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, H. Viehlose Fruchtfolge im Ökologischen Landbau. Auswirkungen Systemeigener und Systemfremder Stickstoffquellen auf Prozesse im Boden und die Entwicklung der Feldfrüchte. Ph.D. Thesis, Univ. Gesamthochschule, Kassel, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, H. Viehloser Öko-Ackerbau; Verlag Dr. Köster: Berlin, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Emmerling, C.; Schröder, D. Ist viehlose Wirtschaft im ökologischen Landbau nachhaltig? In Kongressband 2000; VDLUFA-Schriftenr; Kongressband: Darmstadt, Germany, 2000; Volume 55, pp. 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidtke, K.; Rauber, R. Stickstoffeffizienz von Leguminosen im Ackerbau. In Stickstoffeffizienz Landwirtschaftlicher Kulturpflanzen; Möllers, C., Ed.; Initiativen Umweltschutz 21; E. Schmidt Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2000; pp. 48–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, H. Anwendungsbeispiele zur standortangepassten Humusbilanzierung im ökologischen Landbau. In Standortangepasste Humusbilanzierung im Ökologischen Landbau. Informationen für Praxis, Beratung und Schulung; Landesamt für Umwelt, Landwirtschaft und Geologie (LfULG): Dresden, Germany, 2013; Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/23098/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Kolbe, H. Vergleich von Methoden zur Berechnung der biologischen N2-Fixierung von Leguminosen zum Einsatz in der landwirtschaftlichen Praxis. Pflanzenbauwiss 2009, 13, 23–36. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, S.; Debruck, J. Einfluss der Reihenweite auf Ertrag und Qualität von Winterweizen. Beitr. Wiss.-Tag. Ökol. Landbau Freis. Weihensteph. 2001, 6, 233–236. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, H.J. Optimierungsstrategien für den Getreideanbau im Ökologischen Landbau: System “weite Reihe” und Direktsaat in Ausdauernden Weißklee (Bi-cropping). Ph.D. Thesis, Universität, Kiel, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, K.; Leithold, G. Ausweitung des Anbaukonzeptes Weite Reihe bei Winterweizen auf Roggen, Hafer, Raps und Körnererbsen. Eine pflanzenbauliche und betriebswirtschaftliche Untersuchung unter Berücksichtigung der Vorfruchtwirkungen; Forschungsprojekt 03OE100; JLU Universität Gießen: Gießen, Germany, 2007; Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/14858/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Stumm, C.; Köpke, U. Optimierung des Futterleguminosenanbaus im viehlosen Acker- und Gemüsebau. Beitr. Wiss. Tag. Ökol. Landbau Eberswalde 2015, 13, 1–4. Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/27196/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Casper, S.; Heß, J.; Bruns, C. Transferdüngung mit Kleegras: Auswirkungen verschiedener Düngesubstrate und -stufen auf den Kornertrag von Winterweizen. Beitr. Wiss. Tag. Ökol. Landbau Kassel 2019, 15, 1–4. Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/36240/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Gengenbach, H.; Haase, T. Strategien zur Erzeugung von Qualitätsgetreide in viehlosen/-armen Marktfruchtbetrieben. Beitr. Wiss. Tag. Ökol. Landbau Kassel 2019, 15, 1–5. Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/36259/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Askegaard, M.; Eriksen, J.; Olesen, J.E. Exchangeable potassium and potassium balances in organic crop rotations on a coarse sand. Soil Use Manag. 2006, 19, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbe, H. Einfluss des Klimawandels auf Humus- und Stickstoffvorräte im Boden sowie Kompensationsmöglichkeiten durch Umstellung auf den Ökologischen Landbau am Beispiel von Sachsen, Schriftenr, Landesamt für Umwelt, Landwirtschaft und Geologie (LfULG): Dresden, Germany, 2011, H6, 4–15. Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/19353/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Schulte, G.; Schröder, D. P-und K-Extraktionsverfahren zur Kennzeichnung des Versorgungsgrades unterschiedlich lange ökologisch bewirtschafteter Böden in Rheinland-Pfalz. In Kongressband 1996; VDLUFA-Schriftenr; Kongressband: Darmstadt, Germany, 1996; Volume 44, pp. 437–440. [Google Scholar]

- Leithold, G.; Hülsbergen, K.-J.; Michel, D.; Schönmeier, H. Humusbilanz–Methoden und Anwendung als Agrar-Umweltindikator. In Initiativen Umweltschutz 5; Zeller Verlag: Osnabrück, Germany, 1997; pp. 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, H. Leistungsfähigkeit von Merkmalen der Bodenfruchtbarkeit für das Nährstoffmanagement des ökologischen Landbaus. In Vortragsveranstaltung mit Feldtag “Forschung zum Ökologischen Landbau in Sachsen”; Sächsische Landesanstalt für Landwirtschaft: Roda, Germany, 2006; Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/8975/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Schulz, F.; Brock, C.; Knebl, L.; Leithold, G. Gemischtbetrieb mit Viehhaltung vs. viehloser Ökolandbau. 3. Rotation im Dauerfeldversuch Gladbacherhof. Beitr. Wiss. Tag. Ökol. Landbau Freis. Weihensteph. 2017, 14, 286–289. Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/31955/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Friedel, J.K. HUMUS–Datengrundlage für Treibhausrelevante Emissionen und Senken in Landwirtschaftlichen Betrieben und Regionen Österreichs; Endbericht; Department für Nachhaltige Agrarsysteme, Institut für Ökologischen Landbau, Universität für Bodenkultur: Wien, Austria, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Auerswald, K.; Kainz, M.; Scheinost, A.C.; Sinowski, W. The Scheyern experimental farm: Research methods, farming system and definition of site properties and characteristics. In Ecosystem Approaches to Landscape Management in Central Europe; Tenhunen, J.D., Lenz, R., Hantschel, R., Eds.; Springer Science & Business Media: Berilin, Germany, 2001; Volume 147, pp. 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Raupp, J. Forschungsthemen und Ergebnisse eines Langzeitdüngungsversuchs in zwei Jahrzehnten, ein Beitrag zur Bewertung von pflanzenbaulichen Langzeitversuchen. Ber. Landwirtsch. 2001, 79, 71–93. [Google Scholar]

- Reents, H.J.; Kimmelmann, S.; Kainz, M.; Hülsbergen, K.-J. Biogas-Fruchtfolgeversuch Viehhausen –Versuchsanlage sowie Ertrag- und Qualitätseffekte bei Winterweizen. Beitr. Wiss. Tag. Ökol. Landbau Gießen 2011, 11, 76–80. [Google Scholar]

- Schrama, M.; de Haan, J.J.; Kroonen, M.; Verstegen, H.; Van der Putten, W.H. Crop yield gap and stability in organic and conventional farming systems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 256, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raussen, T.; Richter, F.; Kern, M.; Müller, H.-J.; Gottschall, R.; Bruns, C. Nährstoffrückführung durch Biogut-und Grüngutkomposte in den Ökologischen Landbau Hessens (Öko-Kompost); Endbericht; Hessisches Ministerium für Umwelt, Klimaschutz, Landwirtschaft und Verbraucherschutz (HMUKLV): Wiesbaden, Germany, 2019.

- Harzer, N. Humus-und Nährstoffhaushalt Ökologischer Betriebe und Systemversuche im Land Sachsen-Anhalt. Diploma Thesis, Universität, Halle-Wittenberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann, K. Ökologisch nachhaltiges Betriebsmanagement mit dem Modell REPRO. In Naturland Ackerbautagung Würzburg; Naturland: Gräfelfing, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mitscherlich, E.A. Das Gesetz vom Minimum und das Gesetz des abnehmenden Bodenertrages. Landwirtsch. Jahrb. 1909, 38, 537–552. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, H. Einfluss mineralischer P- und K-Düngung auf die Ertragsreaktion der Fruchtarten in Abhängigkeit von der Nährstoffversorgung des Bodens unter den Anbaubedingungen des ökologischen Landbaus in Deutschland. J. Kulturpflanz. 2019, 71, 161–181. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Werff, P.A.; Baars, A.; Oomen, G.J.M. Nutrient balances and measurement of nitrogen losses on mixed ecological farms on sandy soils in the Netherlands. In Nitrogen Leaching in Ecological Agriculture; Kristensen, L., Stopes, C., Kølster, P., Granstedt, A., Eds.; Proceedings Internat. Workshop; University: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1995; pp. 41–50. [Google Scholar]

- Küstermann, B.; Christen, O.; Hülsbergen, K.-J. Modelling nitrogen cycles of farming systems as basis of site- and farm-specific nitrogen management. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2010, 135, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, F.; Brock, C.; Leithold, G. Viehhaltung im Ökologischen Landbau–ja oder nein? Effekte auf Bodenfruchtbarkeit, N-Bilanzen und Erträge. Beitr. Wiss. Tag. Ökol. Landbau Bonn 2013, 12, 20–23. Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/21379/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Van Delden, A. Yield, and growth components of potato and wheat under organic nitrogen management. Agron. J. 2001, 93, 1370–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, P.M.; Sylvester-Bradley, R.; Philipps, L.; Hatch, D.J.; Cuttle, S.P.; Rayns, F.W.; Gosling, P. Is the productivity of organic farms restricted by the supply of available nitrogen? Soil Use Manag. 2002, 18, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunst, L.; Richner, W.; Mäder, P.; Mayer, J. DOK-Versuch: Nährstoffversorgung in Winterweizen–Wo wird es eng? Agrarforsch. Schweiz 2013, 4, 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Möller, K.; Friedel, J.K. Pflanzenernährung und Düngung. In Ökologischer Landbau–Grundlagen, Wissensstand und Herausforderungen; Freyer, B., Ed.; UTB-Verlagsgruppe, Haupt Verlag: Bern, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 467–485. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, H. Berichte aus dem Ökolandbau 2021–Nährstoffumsatz, Ertrag und Qualität von Kartoffeln. Einfluss mineralischer und organischer Düngemittel auf den Nährstoffumsatz im Boden sowie Ertrag und Qualität von Kartoffeln im Ökologischen Landbau; Dr. H. Kolbe: Schkeuditz, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–144. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:bsz:14-qucosa2-767203 (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Schuphan, W. Mensch und Nahrungspflanze. Der Biologische Wert der Nahrungspflanze in Abhängigkeit von Pestizideinsatz, Bodenqualität und Düngung; Dr. W. Junk Publishers: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, H. Acker- und pflanzenbaulicher, Ökologischer und Ökonomischer Vergleich Verschiedener Landwirtschaftlicher Bewirtschaftungssysteme Unterschiedlicher Intensität und Schlußfolgerungen für Weitere Notwendige Untersuchungen Unter Besonderer Berücksichtigung der Landwirtschaftlichen Bedingungen in den Neuen Bundesländern; Literaturstudie; Institut für Bodenkultur und Pflanzenbau, Sächsische Landesanstalt für Landwirtschaft: Leipzig, Germany, 1993; unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, H. Landnutzung und Wasserschutz. Der Einfluss von Stickstoff-Bilanzierung, Nmin-Untersuchung und Nitrat-Auswaschung Sowie Rückschlüsse für die Bewirtschaftung von Wasserschutzgebieten in Deutschland. Land Use and Water Protection. Effects on Nitrogen Budget, Nmin-values, Nitrate Content and Leaching in Germany; WLV Wissenschaftliches Lektorat & Verlag: Leipzig, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann, H.; Hübner, W. Ökologischer Landbau auf leichten Böden–Ertragsparameter und Bodenfruchtbarkeitskennziffern aus dem Demonstrationsversuch Ackerbausysteme in Blumberg bei Berlin. Beitr. Wiss. Tag. Ökol. Landbau Freis. Weihensteph. 2001, 6, 171–174. [Google Scholar]

- Loges, R.; Taube, F. Nitratauswaschung, Ertrag und N-Bilanz zweier Fruchtfolgen mit unterschiedlichem Leguminosenanteil im mehrjährigen Vergleich. Beitr. Wiss. Tag. Ökol. Landbau Gießen 2011, 11, 89–92. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, C.A.; Bengtsson, H.; Ebbesvik, M.; Loes, A.-K.; Myrbeck, A.; Salomon, E.; Schroder, J.; Stockdale, E.A. A review of farm-scale nutrient budges for organic farms as a tool for management of soil fertility. Soil Use Mangag. 2002, 18, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reimer, M.; Möller, K.; Hartmann, T.E. Meta-analysis of nutrient budgets in organic farms across Europe. Org. Agric. 2020, 10, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abele, U. Einfluss mineralischer und organischer Düngung sowie der biologisch-dynamischen Präparate auf Qualitätsmerkmale pflanzlicher Produkte und auf Bodeneigenschaften. Schriftenr. Bundesminister Ernährung, Landwirtsch. Forsten; Reihe A. Angew. Wiss. 1987, 345. [Google Scholar]

- Köppen, D. Langjährige Entwicklung des Gehaltes an pflanzenverfügbaren Nährstoffen in unterschiedlichen Bodennutzungssystemen. Beitr. Wiss. Tag. Ökol. Landbau Bonn 1997, 4, 122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, H.; Beckmann, U. Einfluss extrem unterschiedlich hoher mineralischer und organischer Düngung und Beregnung auf Ertragsleistung der Kulturarten, Bodenfruchtbarkeit und Umweltverträglichkeit eines Sandbodens. In Umweltwirkungen von Extensivierungsmaßnahmen; Schriftenr, Sächsische Landesanstalt für Landwirtschaft (LfL): Dresden, Germany, 2003; Volume 8, H6, pp. 1–41. Available online: https://publikationen.sachsen.de/bdb/artikel/14035/documents/16492 (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Sauerbeck, D. Funktion, Güte und Belastbarkeit des Bodens aus Agrikulturchemischer Sicht; Verlag W. Kohlhammer: Stuttgart, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, D.; Kolbe, H. Improvement of nitrogen-fertilizer recommendation by consideration of long-term site and cultivation effected mineralization. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2492. Available online: https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy11122492 (accessed on 19 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- Zikeli, S.; Gottschlich, H.; Fürnkranz, M.; Szin, S. Gemüsebau. In Ökologischer Landbau–Grundlagen, Wissensstand und Herausforderungen; Freyer, B., Ed.; UTB-Verlagsgruppe, Haupt Verlag: Bern, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 367–391. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, H.; Köhler, B. Erstellung und Beschreibung des PC-Programms BEFU, Teil Ökologischer Landbau. Verfahren der Grunddüngung, legumen N-Bindung, Nährstoff-und Humusbilanzierung. In BEFU–Teil Ökologischer Landbau; Schriftenr, Landesamt für Umwelt, Landwirtschaft und Geologie (LfULG): Dresden, Germany, 2008; Volume H36, pp. 1–256. Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/15101/ (accessed on 19 July 2002).

- Kolbe, H. Site-adjusted organic matter-balance method for use in arable farming systems. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2010, 173, 678–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolbe, H.; Meinck, S.; Rikabi, F.; Schließer, I. Einfluss von Boden, Klima und Bewirtschaftung auf Corg, Nt und N-Effizienz im Ackerbau. Mathematisch-statistische Auswertungen von Ergebnissen aus Dauerversuchen in Mitteleuropa; Dr. H. Kolbe: Schkeuditz, Germany, 2022; in preparation. [Google Scholar]

- Surböck, A.; Heinzinger, M.; Schmid, H.; Friedel, J.K.; Freyer, B. Auswirkungen unterschiedlicher Leguminosenanteile in der Fruchtfolge auf Humus- und Stickstoffhaushalt. Beitr. Wiss. Tag. Ökol. Landbau Bonn 2013, 12, 164–165. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, J.; Jarosch, K.A.; Hammelehle, A.; Dubois, D.; Gunst, L.; Bosshard, C.; Frossard, E.; Mäder, P.; Oberson, A. Stickstoffbilanzen in biologischen und konventionellen Anbausystemen–Das Effizienz-Nachhaltigkeits-Dilemma. Beitr. Wiss. Tag. Ökol. Landbau Freis. Weihensteph. 2017, 14, 828–831. Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/31925/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Solberg, S.O. Influence of crops and cultivation magagement on the nitrogen leaching potential on ecological farms in south east Norway. In Nitrogen Leaching in Ecological Agriculture; Kristensen, L., Stopes, C., Kølster, P., Granstedt, A., Eds.; Proceedings Internat. Workshop; University of Copenhagen: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1995; pp. 115–121. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, H. Auswirkungen Einer Langjährigen Ökologischen Bewirtschaftung auf Acker-und Pflanzenbauliche Sowie Umweltrelevante Parameter am Standort Gülzow; Abschlussbericht Forschungs-Nr. 4/02; Landesforschungsanstalt für Landwirtschaft und Fischerei Mecklenburg-Vorpommern; Institut für Acker- und Pflanzenbau: Gülzow, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, H. Fruchtfolgegestaltung im ökologischen und extensiven Landbau: Bewertung von Vor-fruchtwirkungen. Pflanzenbauwiss 2006, 10, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, H. Fruchtfolgegrundsätze im Ökologischen Landbau; Faltblatt; Sächsisches Landesamt für Umwelt, Landwirtschaft und Geologie: Dresden, Germany, 2008; Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/15100/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Jarosch, K.A.; Gunst, L.; Dubois, D.; Mäder, P.; Mayer, J. Phosphor- und Kalium-Bilanzen über 35 Jahre DOK-Versuch & geschätzte K-Nachlieferungsraten auf einem Lössboden. Beitr. Wiss. Tag. Ökol. Landbau Freis. Weihensteph. 2017, 14, 318–321. Available online: https://orgprints.org/id/eprint/31861/ (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Thorup-Kristensen, K.; Dresboll, D.B.; Kristensen, H.L. Crop yield, root growth, and nutrient dynamics in a conventional and three organic cropping systems with different levels of external inputs and N re-cycling through fertility building crops. Eur. J. Agron. 2012, 37, 66–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, H.M.; Böhm, H.; Freyer, B. Fruchtfolgen. In Ökologischer Landbau–Grundlagen, Wissensstand und Herausforderungen; Freyer, B., Ed.; UTB-Verlagsgruppe, Haupt Verlag: Bern, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 336–366. [Google Scholar]

- Steffens, D.; Leppin, T.; Luschin-Ebengreuth, N.; Yang, Z.M.; Schubert, S. Organic soil phosphorus considerably contributes to plant nutrition but is neglected by routine soil-testing methods. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2010, 173, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichler-Löbermann, B.; Winklhofer, P.; Zicker, T.; Freitag, F. Phosphorus pools in the soil profile–results of different fertilizer practices over 20 years. In Internat. Arbeitsgemein. Bodenfruchtbarkeit; LTFE-Meeting: Gießen, Germany, 2019; written communication. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, D.; Grandner, N.; Kolbe, H. Strategien zur Optimierung betrieblicher Kohlenstoff- und Stickstoffkreisläufe von landwirtschaftlichen Anbausystemen in Sachsen. In Optimierung von Kohlenstoff- und Stickstoffkreisläufen; Schriftenr, Landesamt für Umwelt, Landwirtschaft und Geologie (LfULG): Dresden, Germany, 2019; Volume H15, pp. 1–138. Available online: https://publikationen.sachsen.de/bdb/artikel/34764/documents/54109 (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Watson, C.A.; Atkinson, D.; Gosling, P.; Jackson, L.R.; Rayns, F.W. Managing soil fertility in organic farming systems. Soil Use Manag. 2002, 18, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelmann, K.; Hülsbergen, K.-J. Stickstoffkreislauf und Stickstoffeffizienz. Nat. Nachr. 2012, 1, 15–17. [Google Scholar]

- Häußermann, U.; Bach, M.; Klement, L.; Breuer, L. Stickstoff-Flächenbilanz für Deutschland mit Regionalgliederung Bundesländer und Kreise–Jahre 1995 bis 2017. Methodik, Ergebnisse und Minderungsmaßnahmen. In Texte 131; Umweltbundesamt: Dessau-Roßlau, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Möller, K.; Habermeyer, J.; Zinkernagel, V.; Reents, H.-J. Impact and interaction of nitrogen and Phytophtora infestans as yield-limiting and yield-reducing factors in organic potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) crops. Potato Res. 2007, 49, 281–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, V. Pflanzenverfügbares Kalium in norddeutschen Sandböden als Grundlage Umweltschonender Kalium-Düngung von Ackerkulturen. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Auerswald, K.; Kainz, M.; Angermüller, S.; Steindl, H. Influence of exchangeable potassium on soil erodibility. Soil Use Manag. 1996, 12, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulff, F.; Schulz, V.; Jungk, A.; Claassen, N. Potassium fertilization on sandy soils in relation to soil test, crop yield and K-leaching. Z. Pflanzenernähr. Bodenk. 1998, 161, 591–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieder, R. Nährstoffanreicherung in Ackerkrumen vor dem Hintergrund des Boden-, Klima- und Gewässerschutzes. Z. Kulturtechn. Landentw. 2000, 41, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Unterschiede Zwischen der EU-Verordnung Ökologischer Landbau und den Richtlinien der Anbauverbände Bioland, Naturland und Demeter; Umweltinstitut München: München, Germany, 2014; Available online: https://www.umweltinstitut.org/fileadmin/Mediapool/Downloads/07_FAQ/Lebensmittel/vergleich_richtlinien.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- The Royal Society. Reaping the Benefits: Science and the Sustainable Intensification of Global Agriculture. 2009. Available online: https://royalsociety.org/~/media/royal_society_content/policy/publications/2009/4294967719.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2022).

- Meemken, E.-M.; Qaim, M. Organic agriculture, food security, and the environment. Ann. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2018, 10, 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Legume Content up to 20% | Legume Content Approx. 33% | Legume Content around 50% | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | ||||||||

| Trial site | Köln-Auweiler | Bernburg | Viehhausen | Villmar | Methau | Spröda | Roda | Roda |

| Altitude (m above sea level) | 48 | 80 | 480 | 160–170 | 265 | 120 | 224 | 224 |

| Trial type | Exact experiment | Exact experiment | Exact experiment | Exact experiment | Exact experiment | Exact experiment | Large plot experiment | Exact experiment |

| Climate | ||||||||

| Mean precipitation (mm per year) | 750 | 469 | 797 | 649 | 693 | 547 | 711 | 711 |

| Mean annual temperature (°C) | 9.5 | 9.1 | 7.5 | 9.5 | 8.4 | 8.8 | 8.6 | 8.6 |

| Soils | ||||||||

| Soil type | Sandy loam | Silty loam | Sandy loam | Strong clayey silt | Loam | Poor loamy sand | Loam | Loam |

| Soil quality index | 65–70 | 85–96 | 61 | 66 | 70/63 | 30/33 | 68 | 68 |

| Clay content (%) | - | 22 | 25 | 24–32 | 15–18 | 5–7 | 12–15 | 13 |

| Cultivation and fertilization system | ||||||||

| Cultivation system | Market crop system with field vegetables | Conventional and organic systems with and without livestock | 6 crop rotation systems in comparison | Forage production, market crop and soil cultivation systems, partial clover-grass mulching, straw fertilization | Forage production (by-products removed), market crop systems (by-products remain, clover-grass mulching) | Forage production (by-products removed), market crop systems (by-products remain, clover-grass mulching) | Typical livestock-less and livestock-rich cropping systems | Legume-rich cropping and fertilization systems |

| Fertilization system (fertilizer types, amount) (1) | Organic commercial fertilizers 0.0, 0.3 LU ha−1 | Stable manure 0.0, 1.0 and 1.5 LU ha−1 | Slurry, stable manure 0.0, 0.8 LU ha−1 | Stable manure 0.0, 0.8 LU ha−1 | Stable manure, slurry, green manure 0.0, 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 LU ha−1 N-mineral fertilization | Stable manure, slurry, green manure 0.0, 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 LU ha−1 N-mineral fertilization | Stable manure, slurry 0.0 and 1.0 LU ha−1 | Stable manure, slurry 0.0, 0.7, 1.3 and 2.7 LU ha−1 |

| Crop rotation | ||||||||

| Clover-grass, grain legumes (share per crop rotation) (%) | Clover-grass, grain legumes 20 | Clover-grass, grain legumes 25 | Clover-grass, grain legumes 33–40 | Clover-grass, grain legumes 33 | Clover-grass 34 | Clover-grass 33 | Clover-grass, grain legumes 33–50 | Clover-grass, grain legumes 50 |

| Cereals (share per crop rotation) (%) | Wheat, winter rye 20–40 | Winter wheat, spring barley, winter rye 63 | Winter wheat, spring barley 33–66 | Winter wheat, winter rye, oats 50 | Winter wheat, spring wheat 33 | Winter wheat, triticale 34 | Winter wheat, spring barley, winter barley, winter rye 33–50 | Winter wheat, winter barley 33 |

| Root crops, corn, field vegetables (share per crop rotation) (%) | Potatoes 20 + field vegetables | Potatoes 12 | Potatoes 0–33 | Potatoes 17 | Potatoes, corn 33 | Potatoes, corn 33 | Potatoes 17 | Potatoes 17 |

| Literature sources | [33] | [34,35,36] | [37,38] | [39] | [40] | [40] | [41] | [42] |

| Trial Variant | Organic Fertilization | GE-Yield | N Balance | P Balance | K Balance | Humus Balance (2) | Nmin Spring | PCAL | KCAL | N Translocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [kg N ha−1] | [t GE ha−1] | [kg N ha−1] | [kg P ha−1] | [kg K ha−1] | [kg HEQ ha−1/Class] | [kg N ha−1 0–90 cm Soil Depth] | [mg P 100 g−1/Class] | [mg K 100 g−1/Class] | [kg N ha−1, 90–200 cm Depth] | |

| Loamy soils | ||||||||||

| Forage production, by-products removed | 37 | 8.2 ± 0.49 | +0 ± 2.5 | −17 ± 3.4 | −120 ± 19.0 | +158 C ± 25.5 | ca. 45 ± 6.1 | 3.9 C ± 0.12 | 7.4 C ± 0.13 | 8.1 ± 0.40 |

| Market crop systems, by-products remain, clover-grass mulching | 33 | 7.8 ± 0.58 | +87 ± 4.5 | −7 ± 2.3 | −14 ± 17.8 | +433 D ± 8.5 | 38 ± 2.2 | 4.3 C ± 0.26 | 11.6 D ± 0.21 | 7.0 ± 0.62 |

| Sandy soils | ||||||||||

| Forage production, by-products removed | 32 | 4.4 ± 0.23 | +14 ± 3.1 | −10 ± 1.1 | −89 ± 16.1 | +82 C ± 12.7 | 40 ± 2.4 | 5.2 D ± 0.28 | 10.4 D ± 0.78 | 18.1 ± 5.3 |

| Market crop systems, by-products remain, clover-grass mulching | 30 | 4.3 ± 0.18 | +83 ± 3.4 | −2 ± 1.5 | −1 ± 9.1 | +214 C ± 25.5 | 45 ± 2.8 | 7.0 D ± 0.12 | 10.7 D ± 1.12 | ca. 19.0 ± 3.2 |

| Mean values (ms) | 33 | 6.2 ± 0.37 | 46 ± 3.4 | −9 ± 2.1 | −56 ± 15.5 | +222 C ± 18.0 | 42 ± 3.4 | 5.1 ± 0.19 | 10.0 ± 0.56 | 13.1 ± 2.4 |

| Trial Variant | Organic Fertilization | GE-Yield | N Balance | P Balance | K Balance | Humus Balance (2) | Nmin Spring | PCAL | KCAL | N Translocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [kg N ha−1] | [t GE ha−1] | [kg N ha−1] | [kg P ha−1] | [kg K ha−1] | [kg HEQ ha−1/Class] | [kg N ha−1] | [mg P 100 g−1/Class] | [mg K 100 g−1/Class] | [kg N ha−1, 90–200 cm Depth] | |

| Loamy soils | ||||||||||

| Forage production, by-products removed | 0 −37 | 7.2 −1.0 (88%) | −24 −24 | −23 −6 (−135%) | −141 −21 (−118%) | +119 C −39 (75%) | 41 −4 (91%) | 3.9 C ±0 (100%) | 7.2 C −0.2 (97%) | 7.0 −1.1 (86%) |

| Market crop systems, by-products remain, clover-grass mulching | 0 −33 | 7.3 −0.5 (94%) | +51 −36 (59%) | −14 −7 (−200%) | −52 −38 (−371%) | +328 D −105 (76%) | 35 −3 (92%) | 4.2 C −0.1 (98%) | 11.1 D −0.5 (96%) | 4.9 −2.1 (70%) |

| Sandy soils | ||||||||||

| Forage production, by-products removed | 0 −32 | 4.0 −0.3 (93%) | −13 −27 | −14 −4 (−140%) | −111 −22 (−125%) | +38 C −44 (46%) | ca. 40 ±0 (100%) | 4.9 D −0.3 (94%) | 8.7 C −1.7 (84%) | 15.0 −3.1 (83%) |

| Market crop systems, by-products remain, clover-grass mulching | 0 −30 | 3.8 −0.5 (88%) | +58 −25 (70%) | −6 −4 (−300%) | −20 −19 (−2000%) | +139 C −75 (65%) | ca. 40 −5 (89%) | 4.8 D −2.2 (69%) | 9.5 C −1.2 (89%) | 16.2 −2.8 (85%) |

| Mean values (ms) | 0 −33 | 5.6 ± 0.3 | +18 ± 4.6 | −14 ± 3.8 | −81 ± 21.0 | +156 ± 54.2 | 39 ± 4.6 | 4.5 ± 0.44 | 9.1 ± 0.88 | 10.8 ± 1.6 |

| Attribute | Loamy Soils | Sandy Soils | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forage Crop | Market Crop | ms | Forage Crop | Market Crop | ms | |

| DM inputs (t ha−1) clover-grass mulch straw organic fertilizer | ||||||

| 0.0 | 5.56 | - | 0.0 | 2.13 | - | |

| 0.0 | 2.08 | - | 0.0 | 1.00 | - | |

| 0.0 | 0.0 | - | 0.0 | 0.0 | - | |

| GE-yield (t ha−1) | 0.0015 | 0.1093 | ±1.69 | −0.0679 | 0.0021 | ±1.97 |

| Corg (% DM) | 0.003375 | 0.009313 | ±0.111 | 0.001071 | 0.003929 | ±0.102 |

| Nt (% DM) | −0.001125 | −0.000312 | ±0.0186 | −0.000786 | −0.000500 | ±0.0212 |

| N mineralization (kg ha−1) | 0.423 | 7.460 | ±61.5 | −3.628 | 1.305 | ±54.6 |

| Nmin spring (kg ha−1) | −1.083 | −0.295 | ±24.7 | 1.393 | 1.255 | ±31.1 |

| Nmin fall (kg ha−1) | 0.583 | 1.487 | ±15.2 | 4.047 | 2.620 | ±57.9 |

| PDL (mg 100 g−1) | −0.095000 | −0.037143 | ±0.52 | −0.183438 | −0.127188 | ±0.82 |

| KDL (mg 100 g−1) | −0.312143 | 0.080714 | ±2.07 | −0.816667 | −0.188438 | ±1.31 |

| MgCaCl2 (mg 100 g−1) | −0.24107 | −0.003125 | ±0.54 | −0.395833 | −0.044844 | ±0.80 |

| Trial Variant | Organic Fertilization | Crop Yield (Main Product) | Legume N2 Fixation | N Balance | P Balance | K Balance | Corg Difference | Humus Balance (HE) (2) | Nmin Spring (0–90 cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [kg N ha−1] | [t DM ha−1] | [kg N ha−1] | [kg N ha−1] | [kg P ha−1] | [kg K ha−1] | [kg Corg ha−1 year−1] | [HEQ ha−1/Class] | [kg N ha−1] | |

| 1 Comparison 1 33% clover-grass | 38 (=100%) | 4.9 (=100%) | 89 (=100%) | +48 (=100%) | −10 (=100%) | −50 (=100%) | +218 (=100%) | +541 E (=100%) | 41 (=100%) |

| 2 16.7% clover-grass, 16.7% grain legumes | 0 | 4.3 −0.6 (78–95%) | 88 −1 (99%) | +45 −3 (=94%) | −12 −2 | −33 +17 | −158 −376 | +315 D −226 | 50 +9 (122%) |

| 3 33% grain legumes | 0 | 3.6 −1.3 (65–83%) | 79 −10 (89%) | +22 −26 | −13 −3 | −29 +21 | −274 −492 | −155 B −696 | 47 +6 (115%) |

| ms | - | ±0.16 | - | - | - | - | ±74 | - | ±3.1 |

| Trial Variant | Organic Fertilization | Crop Yield (Main Products) | Legume N2 Fixation | N Balance | Corg Content Trial End | Humus Balance Supply Level (HE) (2) | Humus Balance (HE) (2) | Nmin Spring (0–90 cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [kg N ha−1] | [t DM ha−1] | [kg N ha−1] | [kg N ha−1] | [% DM] | [%] | [HEQ ha−1/Class] | [kg N ha−1] | |

| 1 Comparison 1 20% clover-grass, by-products removed | 84 | 61 (=100%) | ca. 30 (=100%) | +18 (=100%) | ca. 1.77 (=100%) | 137 | +180 C (=100%) | - |

| 2 Comparison 2 20% clover-grass, by-products ½ removed | 38 | 5.2 −0.9 (85%) | 22 −8 (73%) | +10 −8 (56%) | 1.74 −0.03 (98%) | 121 | +20 C −160 | 39 (100%) |

| 3 20% grain legumes, by-products remain | 29 | 4.5 −1.6 (69–79%) | 30 ±0 (100%) | +8 −10 (44%) | 1.69 −0.14 (96%) | 96 | +78 C −93 | 50 +11 (128%) |

| 4 20% grain legumes, by-products remain | 0 | 4.2 −1.9 (62–75%) | 30 ±0 (100%) | −16 −34 | 1.59 −0.15 (90%) | 44 | −176 B −356 | 47 +8 (121%) |

| ms | - | ±0.18 | - | ±3.03 | ±0.08 | - | ±12.0 | ±3.5 |

| Trial Variant | Organic Fertilization | GE-Yield | N Balance | P Balance | K Balance | Humus Balance (2) | Nmin Spring | PCAL | KCAL | N Translocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [kg N ha−1] | [t GE ha−1] | [kg N ha−1] | [kg P ha−1] | [kg K ha−1] | [kg HEQ ha−1/Class] | [kg N ha−1] | [mg P 100 g−1/Class] | [mg K 100 g−1/Class] | [kg N ha−1, 90–200 cm Depth] | |

| Loamy soils | ||||||||||

| Forage production, by-products removed | 71 | 8.4 | +25 | −8 | −87 | +295 C | 46 | 4.1 C | 7.4 C | 9.8 |

| +34 | +0.2 | +25 | +9 | +33 | +137 | +1 | +0.2 | ±0.0 | +1.8 | |

| (192%) | (102%) | (47%) | (73%) | (187%) | (102%) | (105%) | (100%) | (121%) | ||

| Market crop systems, by-products remain, clover-grass mulching | 65 | 8.0 | +114 | +1 | +27 | +505 E | 47 | 4.5 C | 13.0 D | 8.4 |

| +32 | +0.2 | +27 | +8 | +41 | +72 | +9 | +0.2 | +1.4 | +1.4 | |

| (197%) | (103%) | (131%) | (117%) | (124%) | (105%) | (112%) | (120%) | |||

| Sandy soils | ||||||||||

| Forage production, by-products removed | 63 | 4.3 | +48 | −5 | −51 | +202 C | 50 | 5.4 D | 12.4 D | 19.7 |

| +31 | ±0.0 | +34 | +5 | +38 | +120 | +10 | +0.2 | +2.0 | +1.6 | |

| (197%) | (100%) | (343%) | (50%) | (57%) | (246%) | (125%) | (104%) | (119%) | (109%) | |

| Market crop systems, by-products remain, clover-grass mulching | 59 | 4.3 | +111 | +2 | +23 | +277 C | 51 | 7.8 D | 11.3 D | 19.8 |

| +29 | ±0.0 | +28 | +4 | +24 | +63 | +6 | +0.8 | +0.6 | +0.8 | |

| (197%) | (100%) | (134%) | (129%) | (113%) | (111%) | (106%) | (104%) | |||

| Mean values (ms) | 65 | 6.3 ± 0.27 | +75 ± 2.8 | −3 ± 3.4 | −22 ± 26.5 | +320 ± 47.9 | 49 ± 6.4 | 5.5 ± 0.49 | 11.0 ± 0.65 | 14.4 ± 5.1 |

| Attribute | Loamy Soils | Sandy Soils | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forage Crop | Market Crop | ms | Forage Crop | Market Crop | ms | |

| DM inputs (t ha−1) clover-grass mulch straw organic fertilizer | ||||||

| 0.0 | 5.83 | - | 0.0 | 2.26 | - | |

| 0.0 | 2.17 | - | 0.0 | 1.01 | - | |

| 1.37 | 1.76 | - | 1.95 | 1.59 | - | |

| GE-yield (t ha−1) | 0.0957 | 0.1456 | ±1.99 | −0.0440 | 0.0711 | ±2.00 |

| Corg (% DM) | 0.008375 | 0.014313 | ±0.114 | 0.005714 | 0.007857 | ±0.080 |

| Nt (% DM) | −0.000125 | 0.000375 | ±0.0195 | −0.000250 | −0.000071 | ±0.0190 |

| N mineralization (kg ha−1) | 1.800 | 11.939 | ±63.3 | −3.021 | 2.902 | ±53.2 |

| Nmin spring (kg ha−1) | 0.272 | 0.895 | ±27.8 | 1.645 | 1.297 | ±22.2 |

| Nmin fall (kg ha−1) | 2.008 | 2.472 | ±17.7 | 1.381 | 2.237 | ±47.5 |

| PDL (mg 100 g−1) | −0.060781 | −0.023259 | ±0.70 | −0.029063 | 0.023958 | ±1.01 |

| KDL (mg 100 g−1) | −0.287768 | 0.230804 | ±2.04 | −0.163958 | −0.170156 | ±1.42 |

| MgCaCl2 (mg 100 g−1) | −0.008482 | 0.043750 | ±0.70 | −0.007500 | −0.002083 | ±0.67 |

| Trial Variant | Organic Fertilization | GE-Yield | N Balance | P Balance | K Balance | Humus Balance (2) | Nmin Spring | PCAL | KCAL | N Translocation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [kg N ha−1] | [t GE ha−1] | [kg N ha−1] | [kg P ha−1] | [kg K ha−1] | [kg HEQ ha−1/Class] | [kg N ha−1] | [mg P 100 g−1/Class] | [mg K 100 g−1/Class] | [kg N ha−1, 90–200 cm Depth] | |

| Loamy soils | ||||||||||

| Forage production, by-products removed | 134 | 8.6 | +84 | +9 | −18 | +411 D | 47 | 4.8 D | 8.8 C | 9.0 |

| +97 | +0.4 | +84 | +26 | +102 | +253 | +2 | +0.9 | +1.4 | +1.0 | |

| (362%) | (105%) | (260%) | (104%) | (123%) | (119%) | (111%) | ||||

| Market crop systems, by-products remain, clover-grass mulching | 126 | 8.2 | +167 | +15 | +107 | +631 E | 57 | 5.4 D | 15.2 D | 13.1 |

| +93 | +0.4 | +80 | +22 | +121 | +198 | +19 | +1.1 | +3.6 | +6.1 | |

| (382%) | (105%) | (192%) | (154%) | (150%) | (126%) | (131%) | (187%) | |||

| Sandy soils | ||||||||||

| Forage production, by-products removed | 122 | 4.4 | +101 | +5 | −4 | +288 C | 54 | 5.5 D | 14.1 D | 18.7 |

| +90 | +0.1 | +87 | +15 | +85 | +206 | +14 | +0.3 | +3.7 | +0.6 | |

| (381%) | (102%) | (721%) | (351%) | (135%) | (106%) | (136%) | (103%) | |||

| Market crop systems, by-products remain, clover-grass mulching | 111 | 4.5 | +162 | +9 | +63 | +365 D | 52 | 8.5 D | 12.5 D | 19.1 |

| +81 | +0.2 | +79 | +11 | +64 | +151 | +7 | +1.5 | +1.8 | +0.1 | |

| (370%) | (105%) | (195%) | (171%) | (116%) | (121%) | (117%) | (101%) | |||

| Mean values(ms) | 123 | 6.4 ± 0.35 | +129 ± 7.1 | +10 ± 3.9 | +37 ± 32.8 | +424 ± 59.6 | 53 ± 7.6 | 6.1 ± 0.50 | 12.7 ± 1.52 | 15.0 ± 4.9 |

| Attribute | Loamy Soils | Sandy Soils | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forage Crop | Market Crop | ms | Forage Crop | Market Crop | ms | |

| DM inputs (t ha−1) clover-grass mulch straw organic fertilizer | ||||||

| 0.0 | 5.89 | - | 0.0 | 2.41 | - | |

| 0.0 | 2.16 | - | 0.0 | 1.02 | - | |

| 2.60 | 3.39 | - | 3.77 | 2.99 | - | |

| GE-yield (t ha−1) | 0.1131 | 0.1752 | ±1.97 | −0.0264 | 0.0755 | ±2.15 |

| Corg (% DM) | 0.011656 | 0.017906 | ±0.119 | 0.008179 | 0.010357 | ±0.072 |

| Nt (% DM) | 0.000344 | 0.000938 | ±0.0195 | −0.000107 | 0.000321 | ±0.0181 |

| N mineralization (kg ha−1) | 3.251 | 15.903 | ±59.8 | −2.295 | 5.065 | ±52.7 |

| Nmin spring (kg ha−1) | 0.381 | 1.107 | ±29.8 | 0.161 | 1.095 | ±27.5 |

| Nmin fall (kg ha−1) | 2.662 | 3.247 | ±24.1 | 2.120 | 2.875 | ±55.3 |

| PDL (mg 100 g−1) | 0.007232 | 0.055357 | ±0.93 | 0.014583 | 0.097604 | ±1.35 |

| KDL (mg 100 g−1) | −0.176920 | 0.392857 | ±1.91 | 0.041667 | 0.251563 | ±2.75 |

| MgCaCl2 (mg 100 g−1) | 0.038170 | 0.075446 | ±0.63 | 0.010729 | 0.018750 | ±0.64 |

| Trial Variant (2) | Organic Fertilization | Crop Yield (Main Product) | Legume N2 Fixation | N Balance | Corg Difference | Humus Balance | Nt Difference | Nmin Spring (0–90 cm) | Crude Protein Wheat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [kg N ha−1] | [t DM ha−1] | [kg N ha−1] | [kg N ha−1] | [kg ha−1 year−1] | [kg HEQ ha−1/Class] | [kg N ha−1 year−1] | [kg N ha−1] | [% DM] | |

| 1 = Comparison 1 33% Clover-grass, by-products removed | 45 | 5.3 (=100%) | 71 (=100%) | +23 (=100%) | ±0 (=100%) | −41 B (=100%) | −39 (=100%) | 68 (=100%) | 10.8 (=100%) |

| 2 28% clover-grass + 18% grain legumes, by-products remain, clover-grass mulches | 0 | 5.2 −0.1 (98%) | 75 +4 (106%) | +35 +12 | +540 | +138 C +179 | −18 +21 | 64 −4 (94%) | 10.0 −0.8 (93%) |

| 3 33% clover-grass + 17% grain legumes, by-products removed | 0 0.0 LU ha−1 | 5.2 −0.1 (98%) | 82 +11 (116%) | −2 +25 | +349 | −27 B +14 | −3 +36 | 75 +7 (110%) | 11.2 +0.4 (104%) |

| 4 = Comparison 2 33% clover-grass + 17% grain legumes, by-products removed | 40 0.7 LU ha−1 | 5.9 +0.6 (111%) | 90 +19 (127%) | +34 +11 | +445 | +107 C +148 | +7 +46 | 80 +12 (118%) | 11.6 +0.8 (107%) |

| 5 33% clover-grass + 17% grain legumes, by-products removed | 80 1.3 LU ha−1 | 6.1 +0.8 (115%) | 93 +22 (131%) | +79 +56 | +413 | +217 C +258 | +3 +42 | 83 +15 (122%) | 12.0 +1.2 (111%) |

| 6 33% clover-grass + 17% grain legumes, by-products removed | 160 2.7 LU ha−1 | 5.9 +0.6 (111%) | 90 +19 (127%) | +154 +131 | +571 | +458 D +499 | +16 +55 | 90 +22 (132%) | 12.1 +1.3 (112%) |

| ms | - | ±0.29 | ±4.9 | ±11.5 | - | ±55.0 | - | ±5.9 | ±0.21 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kolbe, H. Comparative Analysis of Soil Fertility, Productivity, and Sustainability of Organic Farming in Central Europe—Part 2: Cultivation Systems with Different Intensities of Fertilization and Legume N2 Fixation as well as Perspectives for Future Development. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2060. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12092060

Kolbe H. Comparative Analysis of Soil Fertility, Productivity, and Sustainability of Organic Farming in Central Europe—Part 2: Cultivation Systems with Different Intensities of Fertilization and Legume N2 Fixation as well as Perspectives for Future Development. Agronomy. 2022; 12(9):2060. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12092060

Chicago/Turabian StyleKolbe, Hartmut. 2022. "Comparative Analysis of Soil Fertility, Productivity, and Sustainability of Organic Farming in Central Europe—Part 2: Cultivation Systems with Different Intensities of Fertilization and Legume N2 Fixation as well as Perspectives for Future Development" Agronomy 12, no. 9: 2060. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12092060

APA StyleKolbe, H. (2022). Comparative Analysis of Soil Fertility, Productivity, and Sustainability of Organic Farming in Central Europe—Part 2: Cultivation Systems with Different Intensities of Fertilization and Legume N2 Fixation as well as Perspectives for Future Development. Agronomy, 12(9), 2060. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12092060