Abstract

Litchi is a highly favored fruit with high economic value. Mechanical automation of litchi picking is a key link for improving the quality and efficiency of litchi harvesting. Our research team has been conducting experiments to develop a visual-based litchi picking robot. However, in the early physical prototype experiments, we found that, although picking points were successfully located, litchi picking failed due to random obstructions of the picking points. In this study, the physical prototype of the litchi picking robot previously developed by our research team was upgraded by integrating a visual system for actively removing obstructions. A framework for an artificial intelligence algorithm was proposed for a robot vision system to locate picking points and to identify obstruction situations at picking points. An intelligent control algorithm was developed to control the obstruction removal device to implement obstruction removal operations by combining with the obstruction situation at the picking point. Based on the spatial redundancy of a picking point and the obstruction, the feeding posture of the robot was determined. The experiment showed that the precision of segmenting litchi fruits and branches was 88.1%, the recognition success rate of picking point recognition was 88%, the average error of picking point localization was 2.8511 mm, and an overall success rate of end-effector feeding was 81.3%. These results showed that the developed litchi picking robot could effectively implement obstruction removal.

1. Introduction

Litchi is a tropical string fruit that is native to southern China. The China Agriculture Research System of Litchi and Longan (CARSLL) data reveal that China produces more than half of the global litchi supply, accounting for more than 60% of the global litchi output [1]. Litchi is a high commercial value fruit due to its ornamental and nutritional values. At present, manual picking of litchis is still the main way to harvest litchis. Aiming at the shortage of agricultural labor population in the future, vigorously developing agricultural automation equipment will be an inevitable trend.

The development of automatic picking robots is of great significance to improve fruit production efficiency and to save labor costs [2]. The fundamental step of automatic fruit picking is to perceive the fruit growth environment and recognize the fruit. Based on actively perceiving devices such as lidar instruments [3], RGB cameras [4], binocular cameras [5], RGB-D cameras [6], and haptic sensors [7], picking robots can recognize the fruit and locate the spatial position of the fruit, and thus plan the picking path to implement picking operations [8].

Surface features of a fruit such as size, shape, texture, and color can be used to recognize the fruit [9,10]. Various methods including convex hull theory-based analysis [11], support vector machine (SVM) classification [12], contour-based analysis [13], morphological analysis [14], and the Ostu algorithm [15] have been used to recognize apple, cucumber, oil palm fruit, citrus, and tomato, respectively, and these techniques have achieved ideal recognition results. However, due to random obstruction interference and the influence of varying lighting in the fruit growing environment, accurate recognition of fruit targets cannot be achieved by developing a single feature-based method.

With the rapid development of deep learning technology, various deep learning networks have been applied in the field of fruit recognition. Salim et al. used DensenNet-201 and Xception deep learning models to identify different types of fruits, which were used in various stages of the production and sales chain of fruits [16]. The object of picking and identifying string-type fruits such as litchi and longan was the fruit bearing branch rather than the fruit itself. The YOLO series of algorithms, as excellent deep learning models, have gradually been exerting their advantages in the field of fruit recognition. For litchi recognition in a natural environment, different types of improved YOLO models have been developed. An improved YOLOv3-Microny network has been used to segment litchi fruits [17]; YOLOv5 models combined with attention mechanism have been used to recognize litchi fruits [18,19]; a YOLACT network has been proposed for litchi main branch recognition [20]. Li et al. used MHSA-YOLOv8 for maturity grading detection and counting of tomato fruits [21]. The above methods achieved ideal recognition of fruits in a non-interference environment; however, when an external interference occurred or the target to be picked was obstructed, the robot did not have the ability to actively resist interference, and then the picking operation on the original recognition result failed or damaged the fruits.

Scholars have used mechanical design theory and visual perception theory to design harvesting robots with the ability to actively resist external interference. Zou et al. designed an end-effector with visual fault tolerance that could be applied to avoid dynamic interferences in picking fruit targets [22]. A generalized picking robot system model has been established to reduce the influence of external disturbances on the picking using a reconstruction method of a robotic cyber-physical system (CPS) [23]. Monocular and binocular visual perception methods combined with digital image processing technology have contributed many ideal examples for resisting external interferences when picking fruits. Xiong et al. used visual perception methods to simulate the movement state of litchi fruits when disturbed and simplified it into pendulum motion to implement picking operations [24]. A monocular visual perception algorithm has been proposed to resist the interference caused by night environment on the recognition and localization of litchi targets by a picking robot [25]. Yin et al. proposed a visual estimation algorithm for citrus posture in unstructured environments to cope with the randomization of fruit growth. They developed and integrated a fully automatic citrus picking robot system with an overall success rate of 87.2% [26]. However, under the influence of dynamic factors such as wind, the visual representation of the disturbed state and the visual perception of the motion characteristics of the robot have not been explored, which needs further study.

Based on the above research status analysis, in this study, we developed a robot active perception system to actively remove random obstructions for litchi picking robots using an artificial intelligence algorithm framework. The random obstruction in this study is the situation where external factors obstruct the litchi fruit picking point that will be cut by the robot. The main contributions of this research are as follows:

- By combining the YOLOv8 model with monocular and binocular image processing technology, a method for identifying and locating litchi picking points was studied.

- An intelligence algorithm was proposed for determining the types of obstructions at the picking points.

- A control method for actively removing obstructions based on visual perception was developed. The feeding and picking posture of the robotic arm was studied.

Experiments was conducted to verify the performance of the proposed method for actively removing obstructions for litchi picking robots.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System and Process of Obstruction Removal

2.1.1. System Composition

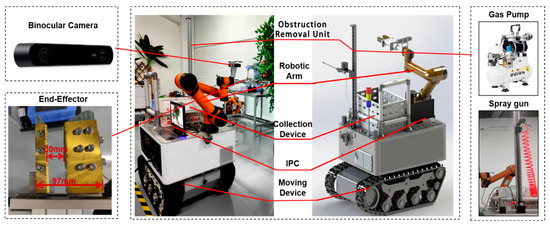

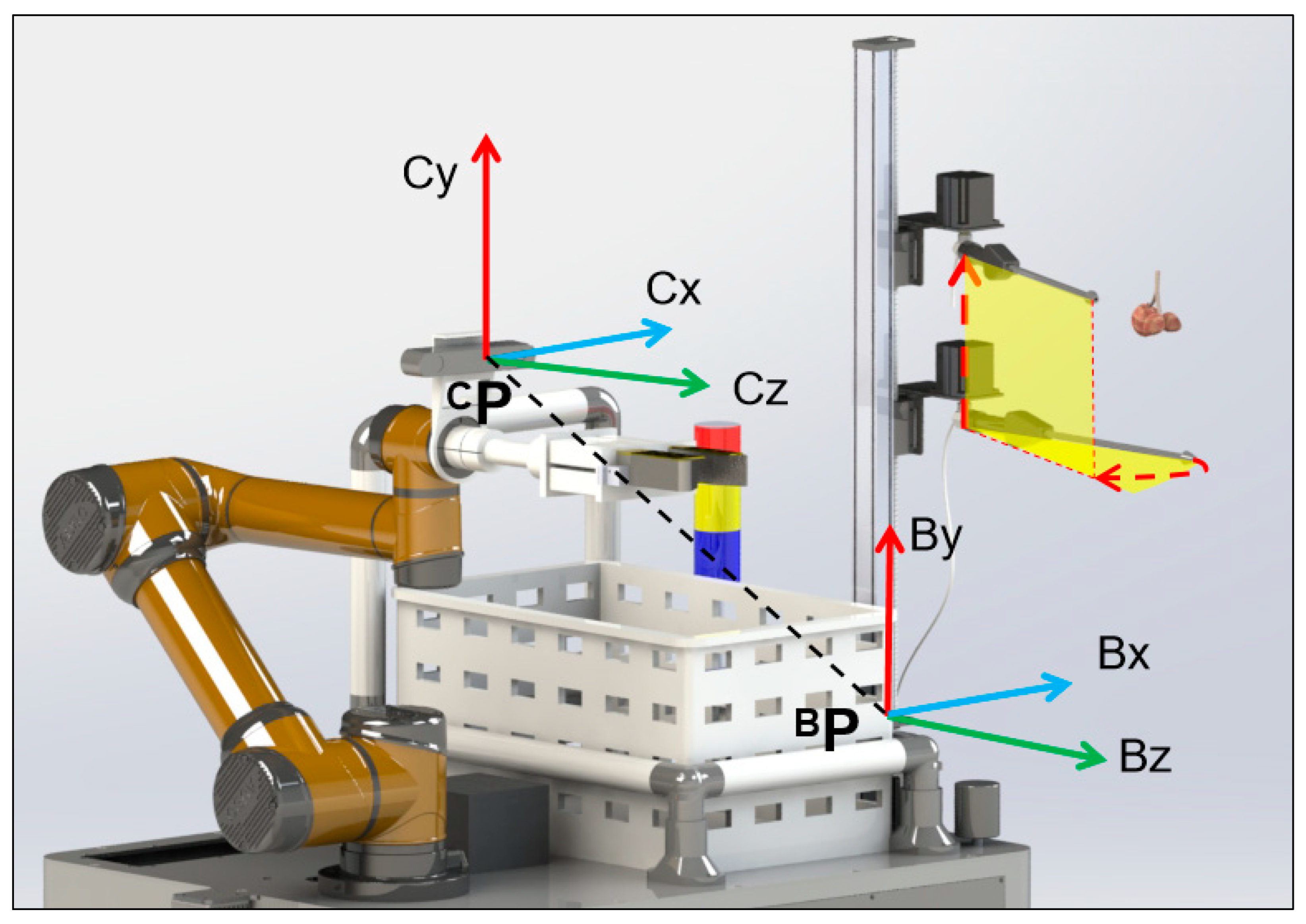

The proposed litchi picking robotic system for actively removing obstructions includes hardware and software components. As shown in Figure 1, the hardware components consist of a robotic arm, an end-effector, a binocular vision camera, an industrial personal computer (IPC), a moving device, a collection device, and an obstruction removal unit. The moving device can move according to a predetermined motion trace. When a litchi target appears in the robot’s field of view, the robot interrupts the motion of the moving device on the predetermined motion trace. Then, the moving device moves in the direction of the target located by the visual system. When it reaches the working range (1367.5 mm) of the robotic, the moving device stops, and the robot performs subsequent operations. The robotic arm is an industrial robotic arm with six degrees of freedom, with a load-bearing capacity of 5 kg. The binocular camera is an RGB-D camera with a baseline length of 120 mm and a focal length of 2.12 mm, which can output images with a resolution of 2208 × 1242 and has a minimum pixel unit of 2 μm × 2 μm. The IPC has configurations of an Intel i5-13600KF processor, with 32G RAM, and a NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4080 GPU (graphics processing unit). The obstruction removal unit consists of a gas pump and a spray gun. The end-effector is a reciprocating scissor type gripper controlled by a cylinder, consisting of a pruning part and a clamping part. By controlling the movement of the pneumatic slider through a pneumatic valve, the end-effector can be opened and closed. When opened, the external width of the end-effector is 97 mm and the internal space width is 10 mm.

Figure 1.

System hardware diagram.

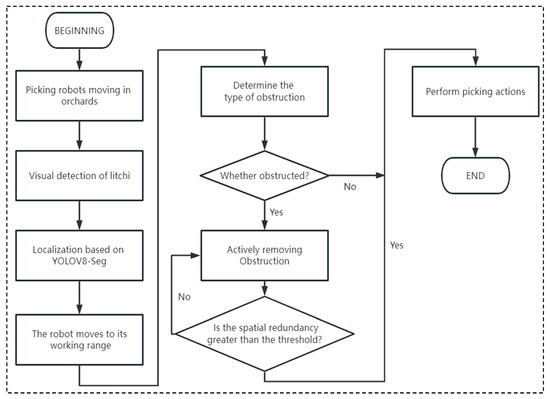

2.1.2. Intelligence Algorithm Process

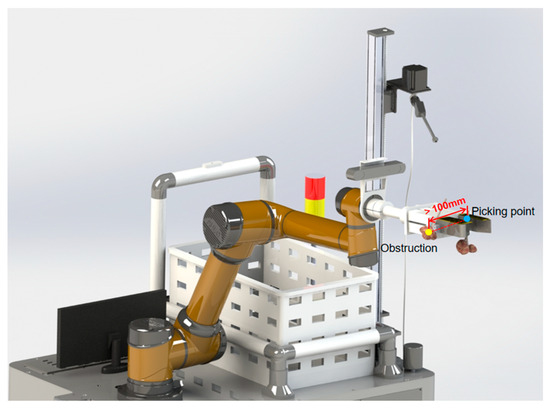

The system software algorithms were developed on the Ubuntu 20.04 system equipped with the ROS Noetic system, and C++ language was applied in programming. The overall process of the proposed algorithms is shown in Figure 2. The mobile device carries the hardware system of the picking robot moving towards a litchi tree. When the litchi fruit is detected by the robot vision system using the YOLOv8-Seg model, binocular stereo vision technology is used to match and locate litchi targets. When the distance between the robot and the located litchi falls within the working range of the robot, determination of the obstruction type at the picking point is implemented. If the picking point is obstructed by the fruit, actively removing the obstruction is implemented by the obstruction removal unit of the robot. If the spatial redundancy between a picking point and an obstructed fruit is greater than the threshold, the end-effector is fed into the spatial redundancy, and then waits for cutting at the picking point. If the spatial redundancy between a picking point and an obstructed fruit is smaller than the threshold, actively removing the obstruction continues to be implemented until the spatial redundancy is greater than the threshold. The threshold was set to 100 mm in this study. If a picking point is not obstructed by the fruit, the end-effector is fed to the picking point for the picking operation.

Figure 2.

Overall process of the software algorithm.

2.2. Localization Method of Picking Points

2.2.1. Localization Process

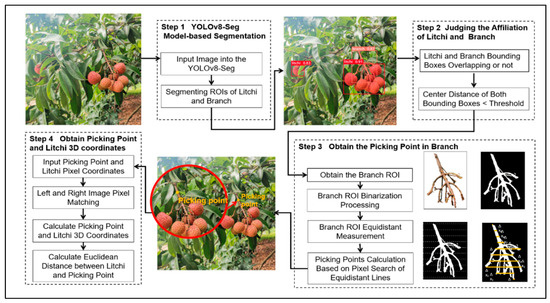

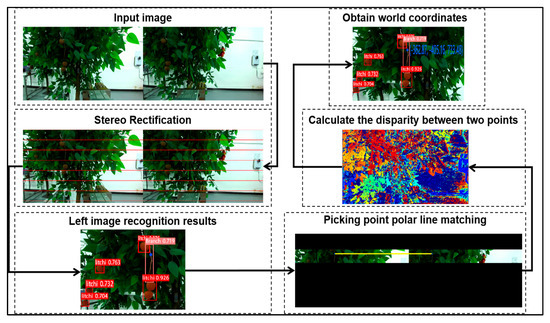

The localization algorithm process is shown in Figure 3. The overall localization algorithm can be divided into four parts. The first part applies the YOLOv8-Seg model in segment litchi images to extract the region of interests (ROIs) of litchi fruits and branches, respectively. The second part involves affiliation determination between the ROIs of the litchi fruits and branches, in which the primary criterion is whether the bounding boxes of the litchi fruits and branches overlap. For cases where the identification boxes of the litchi fruits and branches do not overlap, the affiliation between a litchi fruit and a branch is determined by whether the box center is less than the threshold. The third part is to obtain the picking points on the branch, where the ROIs of the branch are firstly binarized, and then an innovative algorithm based on a pixel search of equidistant lines has been proposed for determining the picking points. In the fourth part, the three-dimensional coordinates of the picking points and litchi fruits are calculated by combining with binocular stereo vision technology, and the Euclidean distances between litchi fruits and picking points are calculated to determine picking point obstructions. The specific details of the above steps will be elaborated in the following sections.

Figure 3.

Algorithm flow of locating picking points.

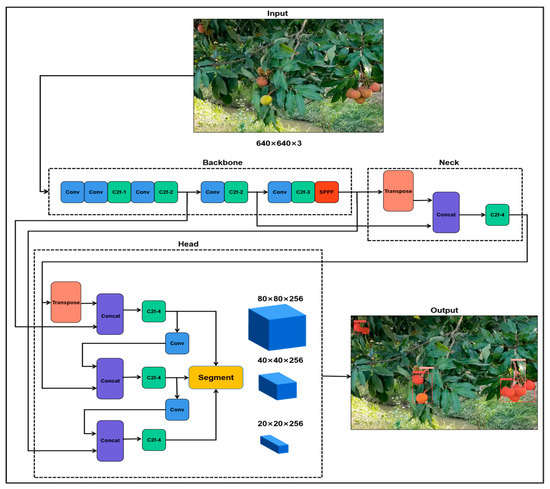

2.2.2. ROIs for Segmentation of Litchi Frutis and Branches

In this study, the YOLOv8-Seg model was directly used for segmentation of litchi fruits and branches without modifying its structure. The segmentation flow of litchi fruits and branches based on the YOLOv8-Seg model is shown in Figure 4. After preprocessing and resizing an original litchi image, it was input into the backbone network of the YOLO8-Seg model. In the backbone network, a series of convolutional kernels were used to extract the features of litchi fruits and branches. After feature extraction, a preliminary feature map was generated. Then, the preliminary feature map was input into the neck network of the YOLO8-Seg model to further extract the target features of litchi fruits and branches, where a feature pyramid was generated and output. Finally, the feature pyramid was input into the head network of the YOLO8-Seg model to generate segmentation areas for litchi fruits and branches. Three different sizes of anchor frames were output. The non-maximum suppression (NMS) function was used to determine whether the anchor frames were retained. The retained anchor frames were located in the contour areas of litchi fruits and branches as their respective ROIs. Thus, the YOLOv8-Seg model-based ROIs for segmentation of litchi fruits and branches were completed.

Figure 4.

Segmentation flow of litchi fruits and branches based on the YOLOv8-Seg model.

After the YOLOv8-Seg model-based segmentation, the affiliation relationships of ROIs between litchi fruits and branches were determined. If the ROIs of the litchi fruits and the branches overlapped, it was considered that the recognized branch belonged to the recognized fruit. If their ROIs did not overlap, the center distance between the litchi fruit bounding box and the branch bounding box was used to determine their affiliation relationship. If the center distance was less than the threshold of 500 pixels, it was considered that the recognized branch belonged to the recognized fruit. If the center distance was greater than the threshold, it was considered that the recognized branch and the recognized fruit did not belong to the same litchi cluster.

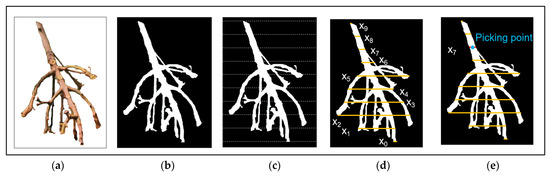

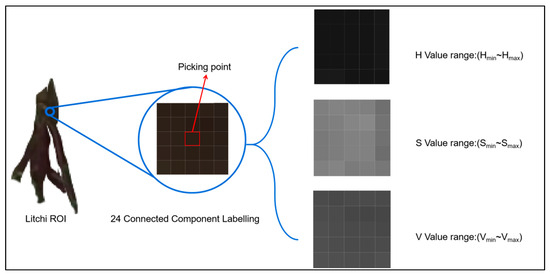

2.2.3. Picking Point Recognition

A proposed picking point recognition flow and its schematic process is shown in Figure 5. For a branch that has completed determination of the fruit affiliation relationship, the ROI of the branch was separately extracted, as shown in Figure 5a. Then, the extracted ROI image of the branch was binarized into a single-valued connected domain, as shown in Figure 5b. Qi et al. segmented the branch image based on the length ratio of the branch to extract the picking point [19]. However, when the litchi branch was long, this segmentation method could cause the picking point to be selected too low, causing the litchi fruit to fall during picking. As shown in Figure 5c, the proposed algorithm divided the binarized image into ten equal parts in the height direction using equidistant lines, and the pixel difference Xi that was also the pixel width on each equidistant line was calculated as shown in Figure 5d. The difference of two adjacent Xi was represented by ∆Xi (∆Xi = Xi − Xi+1), and the difference was compared in sequence. When three consecutive differences ∆Xi, ∆Xi+1, and ∆Xi+2 were all negative and the standard deviation was less than 10 pixels, the picking point would be determined on the equidistant line of Xi+1. Thus, the middle point of Xi+1 was determined as the picking point. For example, the middle point of X7, as shown in Figure 5e, could be determined as the picking point. If there was no equidistant line that met the above condition, the middle point of the highest equidistant line X9 in the branch image was determined as the picking point.

Figure 5.

Recognition flow of the litchi picking point: (a) ROI of a branch; (b) binarized image of the ROI; (c) image with equidistant lines; (d) pixel difference on equidistant lines; (e) picking point recognition.

2.2.4. Picking Point Localization

After the picking point was recognized, the world coordinates of the picking point were obtained by binocular stereo matching. The specific localization process is shown in Figure 6. The input left and right images of the litchi fruit were stereoscopically rectified by substituting left and right camera distortion parameters Dleft and Dright into Equation (1) to eliminate distortion [27] as follows:

where Dleft and Dright are (−0.0432, 0.0126, −0.0003, −0.0005, −0.0058) and (−0.0435, 0.0124, −0.0003, −0.0005, −0.0058), respectively; x and y are the pixel coordinates before the stereo rectification; D is equal to (k1, k2, p1, p2, k3); and r2 = x2 + y2. Using the Bouguet algorithm with rotation and translation matrices, stereo rectification on the left and right images was implemented so that the optical axes of the left and right cameras were parallel, and the height of pixels on the left and right images remained consistent [28]. After recognition of litchi fruits and branches, as shown in the left image recognition results, the left and right images were converted into the HSV color space from the RGB color space. The H color channel in the HSV color space was not affected by lighting and was selected for stereo matching. Using the method in reference [24], the pixel points in the right image were searched for maximum correlation to the left image’s picking point under polar constraints, which was the process of picking point polar line matching.

Figure 6.

Localization flow of litchi picking points.

After picking point matching based on the polar line, the disparity between the left and right images was calculated, and the disparity map was obtained. Then, the reprojection matrix Q was calculated by using rotation and translation matrices and internal reference matrices of left and right cameras. The world coordinates of the picking point could be obtained using the relationship between world coordinates and pixel coordinates, as shown in Equation (2):

where Q is the reprojection matrix, and it was in this study; W is the scale factor; x and y are the pixel coordinates after stereo rectification.

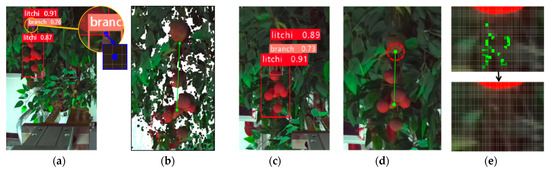

2.3. Obstruction Identification at Picking Points

After calculating the spatial coordinates of the picking point, the robot that carried the binocular camera was ready to move towards the picking point. At this time, the scene in the monocular field of view, as shown in Figure 7a, and the color values of each HSV channel in the 24-pixel field centered on the picking point were recorded as the feature in the 24-pixel field of the picking point. A schematic diagram of this principle is shown in Figure 8. The 24-pixel field was an area of 24 pixels without the center pixel point in a square with a side length of 5 pixels centered on the target point.

Figure 7.

Flow for identifying obstructions at picking points: (a) Remote recognition; (b) distant vector; (c) close range recognition; (d) picking point search; (e) obstruction identification.

Figure 8.

Feature diagram of the 24-pixel field centered on the picking point.

The distance vector between the picking point and the geometric center of the fruit recognition box was recorded as DEuc, as shown in the point cloud image in Figure 7b. Then, the robot that carried the binocular camera moved towards the picking point and stopped moving when the distance between the robot and the picking point fell within the robot’s working range. The litchi fruits and branches were recognized again by the vision system of the robot, as shown in Figure 7c. The geometric center of the litchi fruit recognition box was used as the starting point, and the endpoint was determined using vector DEuc as the direction and length, as shown in Figure 7d. Since the average radius size of litchi fruits in this study was 120 pixels, a circle with a radius of 120 pixels was made centering on the endpoint, as shown in the red dashed circle in Figure 7d. Some green pixels with HSV color features in the picking point 24-pixel field were found within the circle, as shown in the upper row of Figure 7e. However, although these pixels had the color feature of the picking point, they did not have the 24-pixel field connectivity feature of the picking points. Thus, these pixel points were discarded, and the original picking point position was considered to be obstructed by some fruits, as shown in the lower row of Figure 7e.

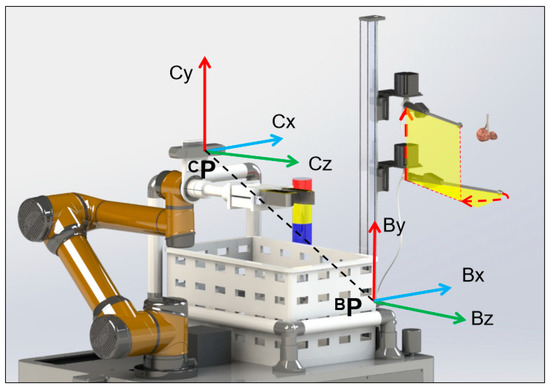

2.4. Obstruction Removal and End-Effector Feeding

2.4.1. Obstruction Removal Method

Coordinate system conversion of the obstruction removal unit is shown in Figure 9. The coordinate system origin of the obstruction removal unit was selected as the output axis of the control motor at the bottom of the unit. The coordinate system BP of the unit was established to be coaxial with the three coordinate axes of the camera coordinate system CP. Therefore, there was a translation relationship between the coordinate system of the binocular camera and the coordinate system of the obstruction removal unit, which could be measured and recorded as BOCP that was equal to . The coordinates of the picking point in the coordinate system of the obstruction removal unit could be solved using Equation (3):

Figure 9.

Coordinate system conversion of the obstruction removal unit.

Figure 9.

Coordinate system conversion of the obstruction removal unit.

2.4.2. Attitude Calculation of End-Effector Feeding

When the robot was performing an obstruction removal operation, the obstructed litchi fruit and the obstructed picking point would separate in space and had their respective motion trace. Frames of the obstructed litchi fruit and the obstructed picking point were captured by the binocular camera at 0.25 s intervals. The distance between the picking point and the geometric frame center of the obstruction was measured by the binocular camera. When the distance was greater than 100 mm, which was the width value of the end-effector, the end-effector would enter the space between the picking point and the obstruction and determine its own picking posture with the picking point at the endpoint, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Diagram of the end-effector entering the space between the picking point and the obstruction.

The Denavit–Hartenberg (D-H) parameters of the robot are shown in Table 1. The transformation matrices ~ of each axis were constructed based on the D-H parameters, where is shown in Equation (5) [29] as:

Table 1.

D-H parameters.

The forward solution equation of the robotic arm was established as shown in Equation (6) [29]:

where are the coordinates of the picking point and is an abbreviation for the result of multiplied by . To simplify calculations, the motion of the end-effector always maintained the camera plane perpendicular to the ground. Using an iterative method to solve numerical solutions for each joint, there were a total of eight sets of numerical solutions for the 6-axis robotic arm. The solutions that made the robotic arm immobile from the eight numerical solutions were discarded, and the optimal solution with the smallest amount of motion for the remaining solutions was calculated.

2.5. Experiments

To validate the effectiveness of the proposed model and algorithm in this study, four sets of experiments were conducted sequentially.

In the first set of experiments, the segmentation performance of the YOLOv8-Seg model was evaluated. The data used for model training were acquired from the litchi orchard situated in Zengcheng District, Guangzhou City, China, using a ZED 2 binocular camera. The labeled data were acquired using the method of manually annotating images through the application of the Labelme 5.2.0 software. The composition information of the dataset is shown in Table 2. The performance during the training process and the segment results of the trained model were recorded and analyzed. Based on the results of the test set segmentation, the picking points were recognized, and the recognition results were recorded as two types, i.e., success or failure.

Table 2.

Dataset composition table.

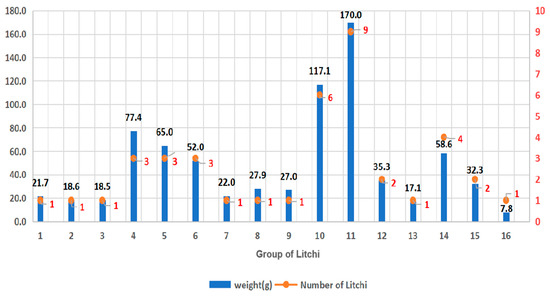

In the second set of experiments, 16 clusters of litchi fruits were selected; the weight and count of litchi fruits within each cluster are shown in Figure 11. The litchi clusters were randomly paired and allocated into 16 groups. The distance value between the camera and the recognized picking point was measured by using the binocular vision unit of the proposed system, which was recorded as the measured value. The real distance value between the camera and the recognized picking point was obtained by using a laser range finder (supplied by Step Test Technology Co., Ltd. in Shenzhen, China), with a measurement error of ±1.5 mm within the range of 60,000 mm. The error between the measured value and the real value was analyzed.

Figure 11.

The weight of litchi clusters and the number of fruits per cluster.

In the third set of experiments, the success rate of obstruction identification at picking points was tested using the method proposed in Section 2.3. The obstruction situations were defined as follows:

- (a)

- In the first situation, the picking point was identified; however, the Euclidean distance between the picking point and the obstructed litchi cluster was smaller than the width of the end-effector, i.e., 97 mm.

- (b)

- In the second situation, the picking point was not identified, and the pixels at the picking point were identified as belonging to the obstructed litchi cluster.The unobstructed situations were defined as follows:

- (i)

- In first situation, the picking point was not identified, and the pixels at the picking point were classified as objects other than a picking point and litchi fruits.

- (ii)

- In the second situation, the picking point was identified, and the distance between the picking point and the obstructed litchi cluster surpassed the end-effector’s width.

Sixteen pairs of litchi clusters were tested, and the identification results were recorded and analyzed by comparing to the actual results.

In the fourth set of experiments, the obstruction removal performance of the proposed system was evaluated. Sixteen experiments were undertaken throughout the air-blowing process and images were captured by the camera at a 0.25 s interval. The positions of both the picking point and the obstruction were documented, and their motion traces were fitted based on these positions. The maximum distance between the picking point and the obstruction during their movement was computed. The feeding execution of the end-effector was determined through a comparison of the maximum distance with the end-effector’s width threshold, and these results were recorded and subjected to analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

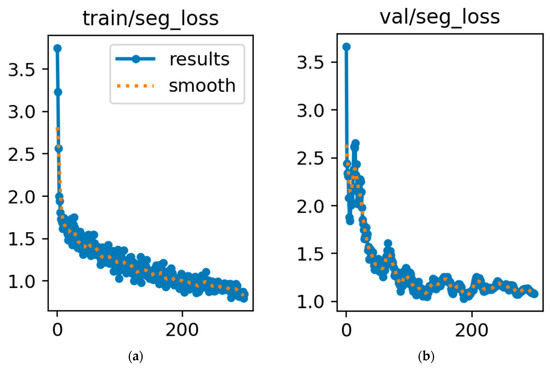

3.1. Identification Results and Analysis of Picking Points

Figure 12 shows two sets of loss convergence curves of the YOLOv8-Seg model representing the loss function changing of the training set and the loss function changing of the verification set, represented by the train_loss curve and the val_loss curve, respectively. For the train_loss curve, as shown in Figure 12a, the smoothed result has a fast descent speed and a stable descent trend, and after 200 iterations, the curve steadily converges to a value close to zero. This indicates a high matching degree between the training set and the model structure, which enables the model to efficiently obtain the features of the training set. However, although the val_loss curve, as shown in Figure 12b, has a fast descent speed and a small convergence value, the smoothing result shows significant trembling, which implies that the YOLOv8-Seg model can successfully complete segmentation of litchi fruits and branches, but the unmodified model structures are susceptible to the influence of randomly identifying target features in unstructured environments. A similar result can be found in reference [30].

Figure 12.

The loss curve of the YOLOv8-Seg model: (a) train/seg_loss; (b) val/seg_loss.

The performance parameters of the YOLOv8-Seg model are shown in Table 3. It can be seen that the network size of the model was 6.45 MB, precision was 88.1%, recall was 86.0%, the F1score was 87.04, and mAP was 78.1. The high accuracy and mAP indicated that the model could accurately recognize different types of targets. A high recall rate indicated that the model could segment all targets in the image without missing them. A high F1score indicated that the model achieved a good balance between accurate recognition and retrieval. Therefore, the Yolov8-Seg model had advantages in size and detection performance, which made the model suitable for deployment in the small processing unit of the litchi picking robot.

Table 3.

Model performance parameters.

The segmentation results of indoor and outdoor litchi images using the YOLOv8-Seg model are shown in Figure 13. It can be observed that the model could accurately segment litchi fruits and branches in different environments.

Figure 13.

Segmentation results of litchi images: (a) Indoor litchi image; (b) outdoor litchi image.

According to the segmentation results, the picking points were identified. Two cases of failed recognition are shown in Figure 14. After comparing the successful results of other image recognition, the reason for the failure to identify branches of litchi may be due to overexposure of the background and dim light. The reason for the failure to locate the picking point was that the algorithm did not take into consideration the elevation angle between the litchi fruit and branch, as well as the distance between a single fruit and the fruit string in the litchi string.

Figure 14.

Two cases of failed recognition: (a) Unable to identify litchi branch; (b) picking point localization error.

For the 100 images in the test set, the recognition results are recorded in Table 4. For 70 outdoor litchi images, the success rate of picking point recognition was 91.42%, and the average recognition time was 81.23 ms. For 30 indoor litchi images, the success rate of picking point recognition was 83.33%, and the average recognition time was 78.21 ms. The success rate of picking point recognition in the overall image was 88%, and the average recognition time was 80.32 ms. The proposed picking point recognition method had advantages both in success rate and in processing time, so it could quickly and accurately identify the target picking points, which could be applied in the real-time operation of a litchi picking robot.

Table 4.

Picking point recognition results.

3.2. Localization Results and Analysis of Picking Points

There are 16 groups of real distances and measured distances shown in Table 5. The results indicated that the maximum error between the real distances and the measured distances was 7.7600 mm, the minimum error was 0.0708 mm, and the average error was 2.8511 mm. All errors were within the fault-tolerant picking range of the robotic arm. Thus, the measured method could meet the operation requirements of the litchi picking robot (Table 5).

Table 5.

Distance values measured by two methods.

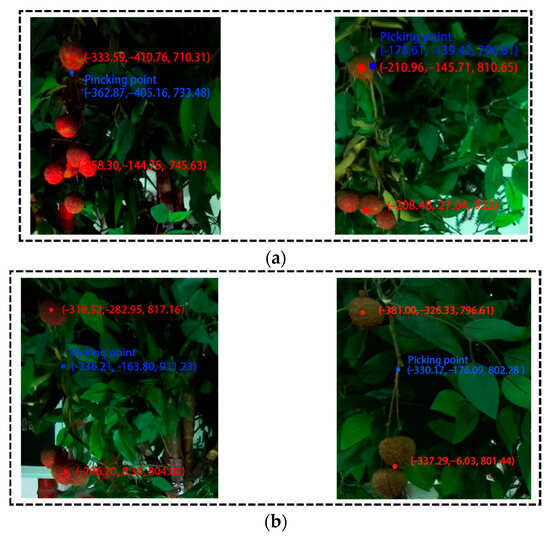

3.3. Identification Results and Analysis of Obstruction Types

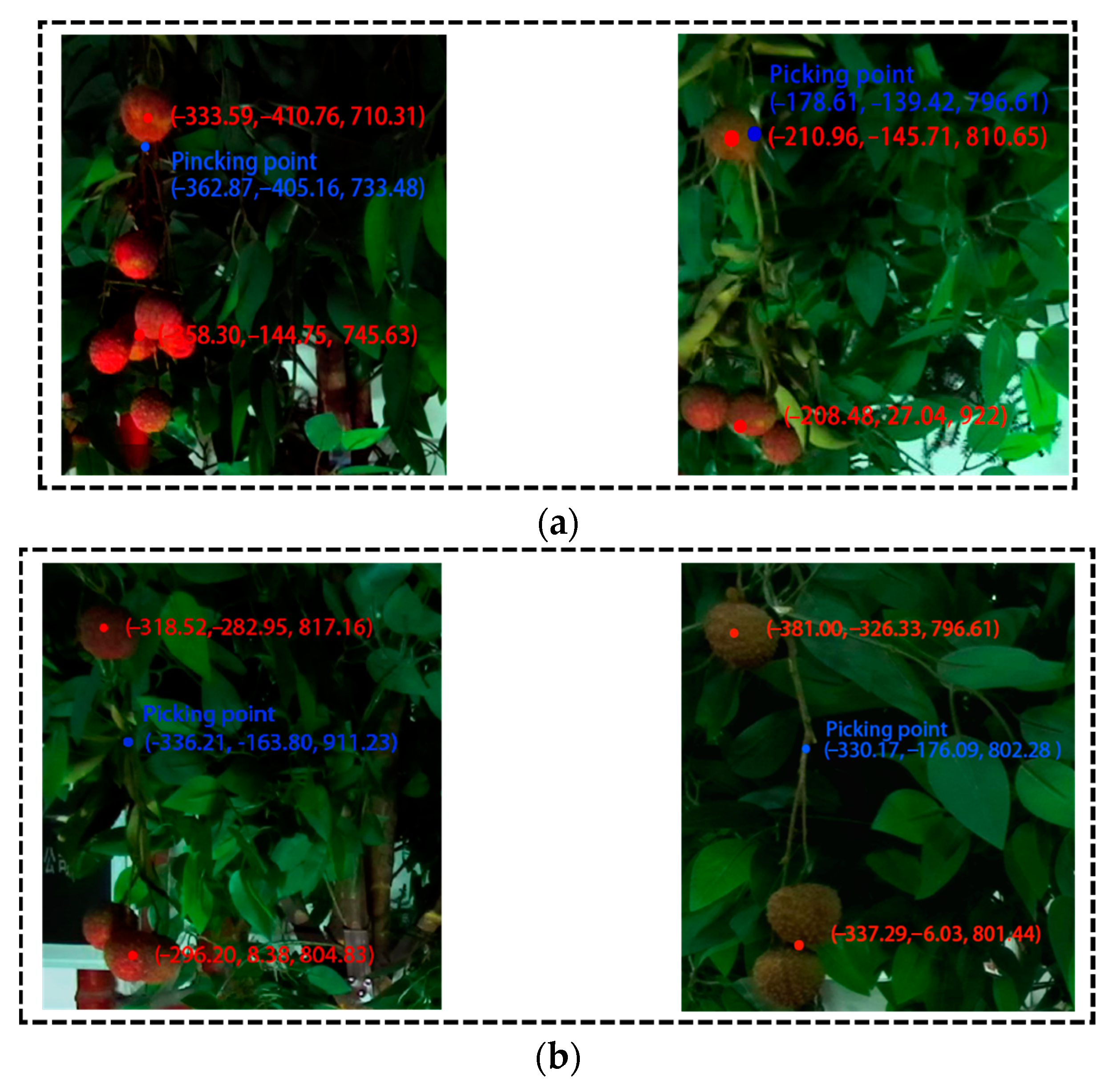

The identification results of two situations are shown in Figure 15. In Figure 15a, the picking point was identified, and the Euclidean distance between the picking point and the litchi fruit next to it was smaller than the threshold. An obstruction situation was correctly identified. In Figure 15b, the picking point was identified, and the distance between the picking point and the litchi cluster was greater than the threshold. An unobstructed situation was correctly identified. This shows that the proposed algorithm of obstruction type identification is effective.

Figure 15.

Identification results of the two situations: (a) Obstruction situation; (b) unobstructed situation.

The specific results of the obstruction identification experiment are shown in Table 6. The proposed method achieved a 100% accuracy rate in identifying actual obstruction situations, which could verify the accuracy of the proposed method.

Table 6.

Identification results of obstruction types.

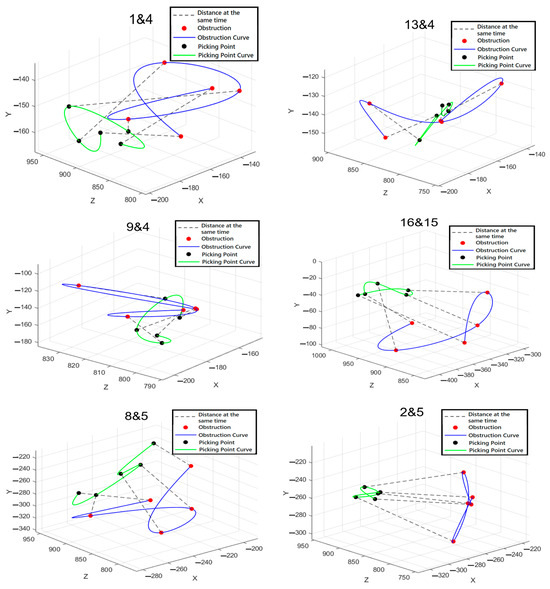

3.4. Results and Performance Analysis of Obstruction Removal

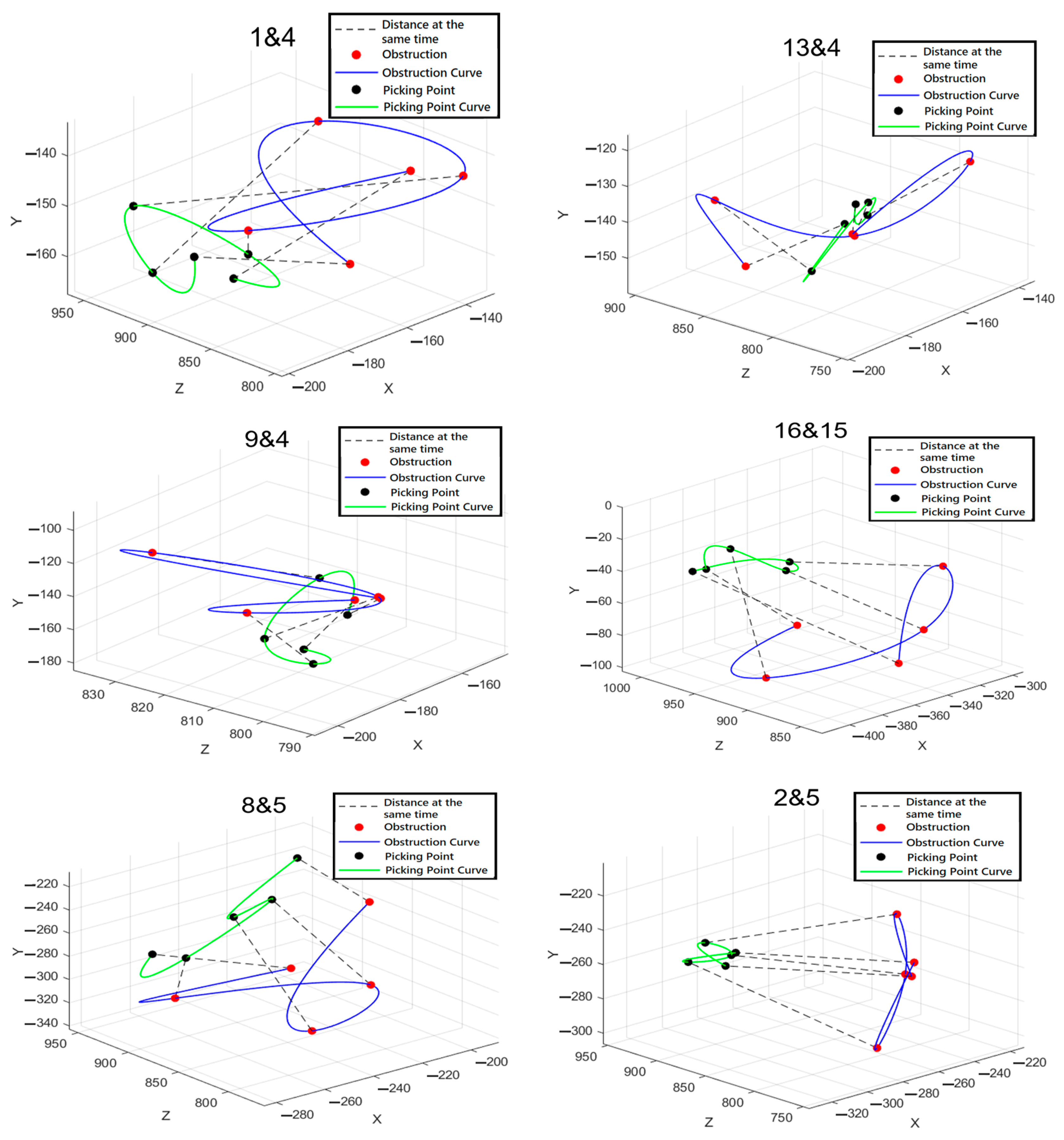

3.4.1. Results and Analysis of the Motion Traces

Six groups of representative motion traces of picking points and obstructed litchi fruits are shown in Figure 16. All motion traces exhibited irregular movements during the obstruction removal. Since the center of the obstructed litchi fruits was close to the spray gun, the movement amplitudes of the obstructed litchi fruits were greater than those of the picking points. It can be seen from the figures that the two motion traces are clearly separated and there is a significant spatial redundancy between the two motion traces, which provides a foundation for the end-effector to enter the space redundancy for picking. This proves that the proposed method is effective for obstruction removal.

Figure 16.

Six groups of representative motion traces of picking points and obstructed litchi fruits.

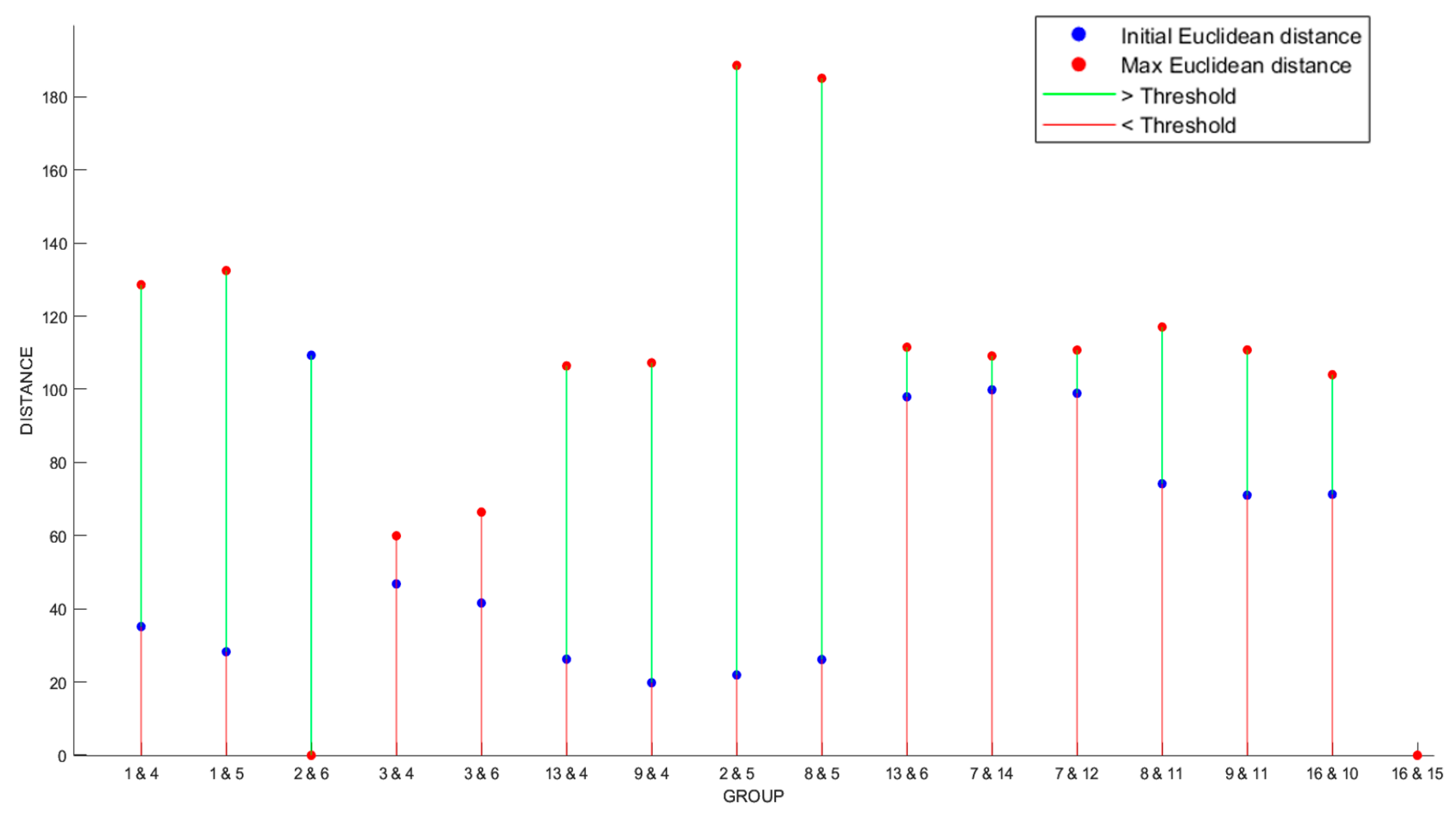

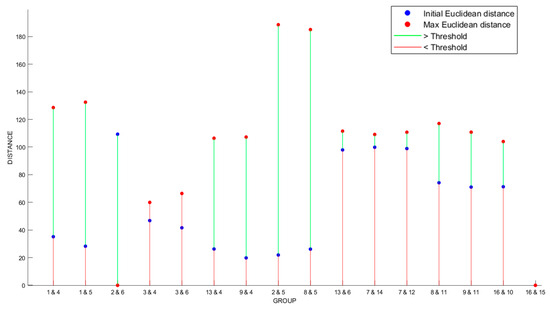

3.4.2. Results and Analysis of End-Effector Feeding

There are 16 litchi clusters shown in Figure 11, which were randomly divided into 16 pairs, forming the horizontal coordinates of Figure 17 in the form of Num 1 and Num 2. Num 1 and Num 2 represent the obstructed litchi cluster and the litchi cluster to be picked, respectively. The vertical coordinates of Figure 17 represent the initial Euclidean distance between the obstructed litchi cluster and the picking point of each paired group, as well as the maximum Euclidean distance between the two after obstruction removal. It can be observed that the distances between the initial Euclidean distance and the maximum Euclidean distance in 13 pairs are greater than the threshold, and those in the other 3 pairs are smaller than the threshold. An overall success rate of 81.3% could be obtained, which showed the feasibility of successful entry of the end-effector into the space redundancy between an obstructed litchi cluster and the picking point. It also implied that the method of obstruction removal based on visual recognition and localization was effective and feasible, and for this success, it is fundamental that the end-effector can feed into the space redundancy between an obstructed litchi cluster and the picking point.

Figure 17.

Initial Euclidean distance and maximum Euclidean distance after obstruction removal.

4. Conclusions

This study proposed a litchi picking robot system that was capable of actively removing obstructions. The system applied the YOLOv8-Seg model to segment litchi fruits and branches. An intelligent image algorithm was developed for recognizing litchi picking points. Binocular vision technology was used for localizing the recognized litchi picking points. An intelligent algorithm framework was developed for identifying the obstruction types at the picking points. Obstruction removal at a picking point was actively implemented based on the recognition results of the robot vision system and the obstruction removal unit. The end-effector of the robot system was controlled to successfully enter the space redundancy between the obstructed litchi cluster and the picking point. Some conclusions include the following:

- The comprehensive performance results of using the YOLOv8-Seg model to segment litchi fruits and branches were that precision was 88.1%, recall was 86.0%, the F1score was 87.04, and mAP was 78.1.

- The recognition success rate of picking point recognition was 88%, and the average recognition time was 80.32 ms.

- The maximum error, the minimum error, and the average error of picking point localization using binocular vision technology were 7.7600 mm, 0.0708 mm, and 2.8511 mm, respectively.

- A 100% accuracy rate in identifying obstruction situations was achieved by using the proposed method.

- An overall success rate of 81.3% was obtained for end-effector entry into the space redundancy between obstructed litchi clusters and picking points based on actively removing obstructions.

These conclusions confirmed that the developed litchi picking robot had effective performance for actively removing obstructions. In future research, the posture of the cutting picking point of a litchi cluster will be the focus based on a lichi picking robot with actively removing obstruction capabilities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.W., C.L. and Q.H.; methodology, C.W. and F.W.; investigation, C.L. and Q.H.; resources, F.W. and X.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, C.L.; writing—review and editing, C.W. and C.L.; project administration, X.Z.; funding acquisition, C.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 52005069) and the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (grant number 2022A1515140162).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

We declare that we do not have any commercial or associative interest that represent any conflicts of interest in connection with the work submitted.

References

- Li, H.; Huang, D.; Ma, Q.; Qi, W.; Li, H. Factors Influencing the Technology Adoption Behaviours of Litchi Farmers in China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Z.; Huang, K.; Jia, G.; Lei, H.; Cai, Y.; Zhong, Z. An effective litchi detection method based on edge devices in a complex scene. Biosyst. Eng. 2022, 222, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda, D.; Fernandez, R.; Navas, E.; Armada, M.; Gonzalez-De-Santos, P. Robotic Aubergine Harvesting Using Dual-Arm Manipulation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 121889–121904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguiar, A.S.; Magalhaes, S.A.; dos Santos, F.N.; Castro, L.; Pinho, T.; Valente, J.; Martins, R.; Boaventura-Cunha, J. Grape Bunch Detection at Different Growth Stages Using Deep Learning Quantized Models. Agronomy 2021, 11, 1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W.; Wen, H.; Ning, Z.; Ye, J.; Dong, Z.; Luo, L. Fruit Detection and Pose Estimation for Grape Cluster-Harvesting Robot Using Binocular Imagery Based on Deep Neural Networks. Front. Robot. AI 2021, 8, 626989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, L.; Xiong, J.; Fang, X.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Lin, X.; Chen, S. A litchi fruit recognition method in a natural environment using RGB-D images. Biosyst. Eng. 2021, 204, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilay, K.; Mandal, S.; Agarwal, Y.; Gupta, R.; Patel, M.; Kumar, S.; Shah, P.; Dey, S.; Annanya. A Proposal of FPGA-Based Low Cost and Power Efficient Autonomous Fruit Harvester. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Control, Automation and Robotics (ICCAR), Singapore, 20–23 April 2020; pp. 324–329. [Google Scholar]

- Magalhaes, S.A.; Moreira, A.P.; dos Santos, F.N.; Dias, J. Active Perception Fruit Harvesting Robots—A Systematic Review. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2022, 105, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.D.; Xu, H.; Xu, L.M.; Zou, L.; Rong, H.L.; Yang, B.; Niu, L.L.; Ma, Z.H. Recognition of fruits and vegetables with similar-color background in natural environment: A survey. J. Field Robot 2022, 39, 888–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.C.; Chen, M.Y.; Wang, C.L.; Luo, L.F.; Li, J.H.; Lian, G.P.; Zou, X.J. Recognition and Localization Methods for Vision-Based Fruit Picking Robots: A Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.L.; Zhou, W.C.; Wang, D.D.; He, D.J.; Zhang, H.H.; Song, H.B. Extracting the symmetry axes of partially occluded single apples in natural scene using convex hull theory and shape context algorithm. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2017, 76, 14075–14089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, S.H.; Li, Y.H.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, B.H.; Zhou, J.; Wang, K. Automatic cucumber recognition algorithm for harvesting robots in the natural environment using deep learning and multi-feature fusion. Comput. Electron. Agriculture 2020, 170, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Septiarini, A.; Hamdani, H.; Hatta, H.R.; Anwar, K. Automatic image segmentation of oil palm fruits by applying the contour-based approach. Sci. Hortic. 2020, 261, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.J.; Luo, S.M.; Hou, C.J.; Tang, Y.; He, Y.; Xue, X.Y. Detection of orchard citrus fruits using a monocular machine vision-based method for automatic fruit picking applications. Comput. Electron. Agriculture 2018, 152, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, J.J.; Hou, C.J.; Tang, Y.; He, Y.; Guo, Q.W.; Zhong, Z.Y.; Luo, S.M. Computer vision-based localisation of picking points for automatic litchi harvesting applications towards natural scenarios. Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 187, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, F.; Saeed, F.; Basurra, S.; Qasem, S.N.; Al-Hadhrami, T. DenseNet-201 and Xception Pre-Trained Deep Learning Models for Fruit Recognition. Electronics 2023, 12, 3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Lin, J.Q.; Li, B.Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, J. Partition harvesting of a column-comb litchi harvester based on 3D clustering. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 197, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.X.; Peng, J.J.; Wang, J.X.; Chen, B.H.; Jing, T.W.; Sun, D.Z.; Gao, P.; Wang, W.X.; Lu, J.Q.; Yetan, R.; et al. Litchi Detection in a Complex Natural Environment Using the YOLOv5-Litchi Model. Agronomy 2022, 12, 3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.K.; Dong, J.S.; Lan, Y.B.; Zhu, H. Method for Identifying Litchi Picking Position Based on YOLOv5 and PSPNet. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Xiong, J.T.; Zheng, Z.H.; Liu, B.L.; Liao, S.S.; Huo, Z.W.; Yang, Z.G. A method for litchi picking points calculation in natural environment based on main fruit bearing branch detection. Comput. Electron. Agriculture 2021, 189, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zheng, J.S.; Li, P.Y.; Long, H.W.; Li, M.; Gao, L.H. Tomato Maturity Detection and Counting Model Based on MHSA-YOLOv8. Sensors 2023, 23, 6701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Ye, M.; Luo, C.; Xiong, J.; Luo, L.; Wang, H.; Chen, Y. Fault-Tolerant Design of a Limited Universal Fruit-Picking End-Effector Based on Vision-Positioning Error. Appl. Eng. Agric. 2016, 32, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Wang, Z.H.; Guo, S.H. State Estimation and Attack Reconstruction of Picking Robot for a Cyber-Physical System. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.T.; He, Z.L.; Lin, R.; Liu, Z.; Bu, R.B.; Yang, Z.G.; Peng, H.X.; Zou, X.J. Visual positioning technology of picking robots for dynamic litchi clusters with disturbance. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 151, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.T.; Liu, Z.; Lin, R.; Bu, R.B.; He, Z.L.; Yang, Z.G.; Liang, C.X. Green Grape Detection and Picking-Point Calculation in a Night-Time Natural Environment Using a Charge-Coupled Device (CCD) Vision Sensor with Artificial Illumination. Sensors 2018, 18, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.S.; Sun, Q.X.; Ren, X.; Guo, J.L.; Yang, Y.L.; Wei, Y.J.; Huang, B.; Chai, X.J.; Zhong, M. Development, integration, and field evaluation of an autonomous citrus-harvesting robot. J. Field Robot. 2023, 40, 1363–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.Y.; Ren, X.Y.; Du, Y.F.; Yuan, F.; He, X.Y.; Yang, F.J. Binocular camera calibration based on timing correction. Appl. Optics. 2022, 61, 1475–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxime, F.; Alexandre, E.; Julien, M.; Martial, S.; Guy, L.B. OV2SLAM: A Fully Online and Versatile Visual SLAM for Real-Time Applications. IEEE Robot Autom. Let. 2021, 6, 1399–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.Y.; Zou, T.; Jiang, X.T. A Neural Network Based Approach to Inverse Kinematics Problem for General Six-Axis Robots. Sensors 2022, 22, 8909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Qi, K.; Na, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.H.; Liu, C.H. Improved YOLOv8-Seg Network for Instance Segmentation of Healthy and Diseased Tomato Plants in the Growth Stage. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).