Using Low-Cost Proximal Sensing Sensors for Detecting the Water Status of Deficit-Irrigated Orange Orchards in Mediterranean Climatic Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Orange Orchards of Interest

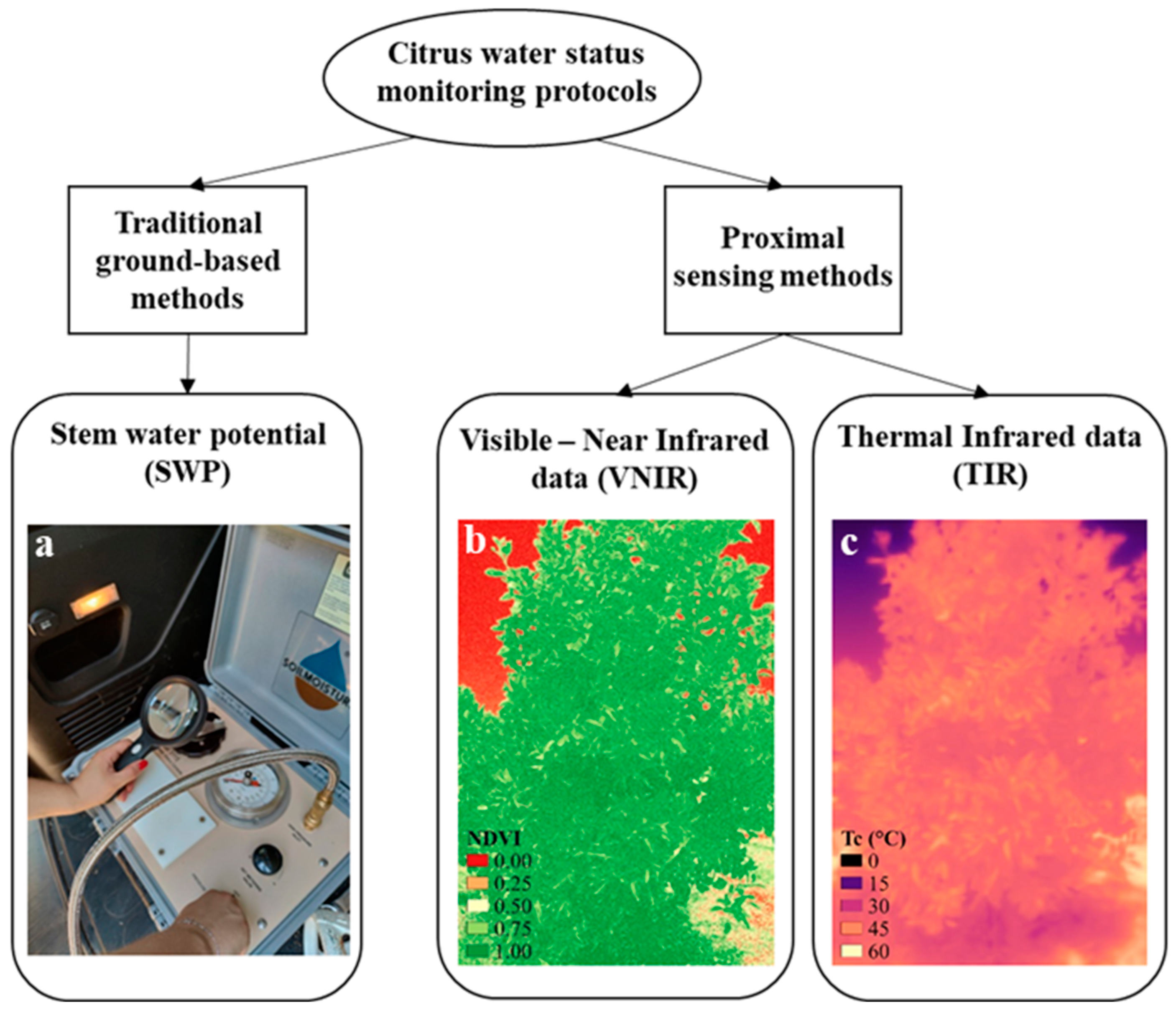

2.2. Methodological Approach

2.2.1. Stem Water Potential Measurements

2.2.2. Multispectral Measurements

2.2.3. Thermal Measurements

2.2.4. Statistical Analysis

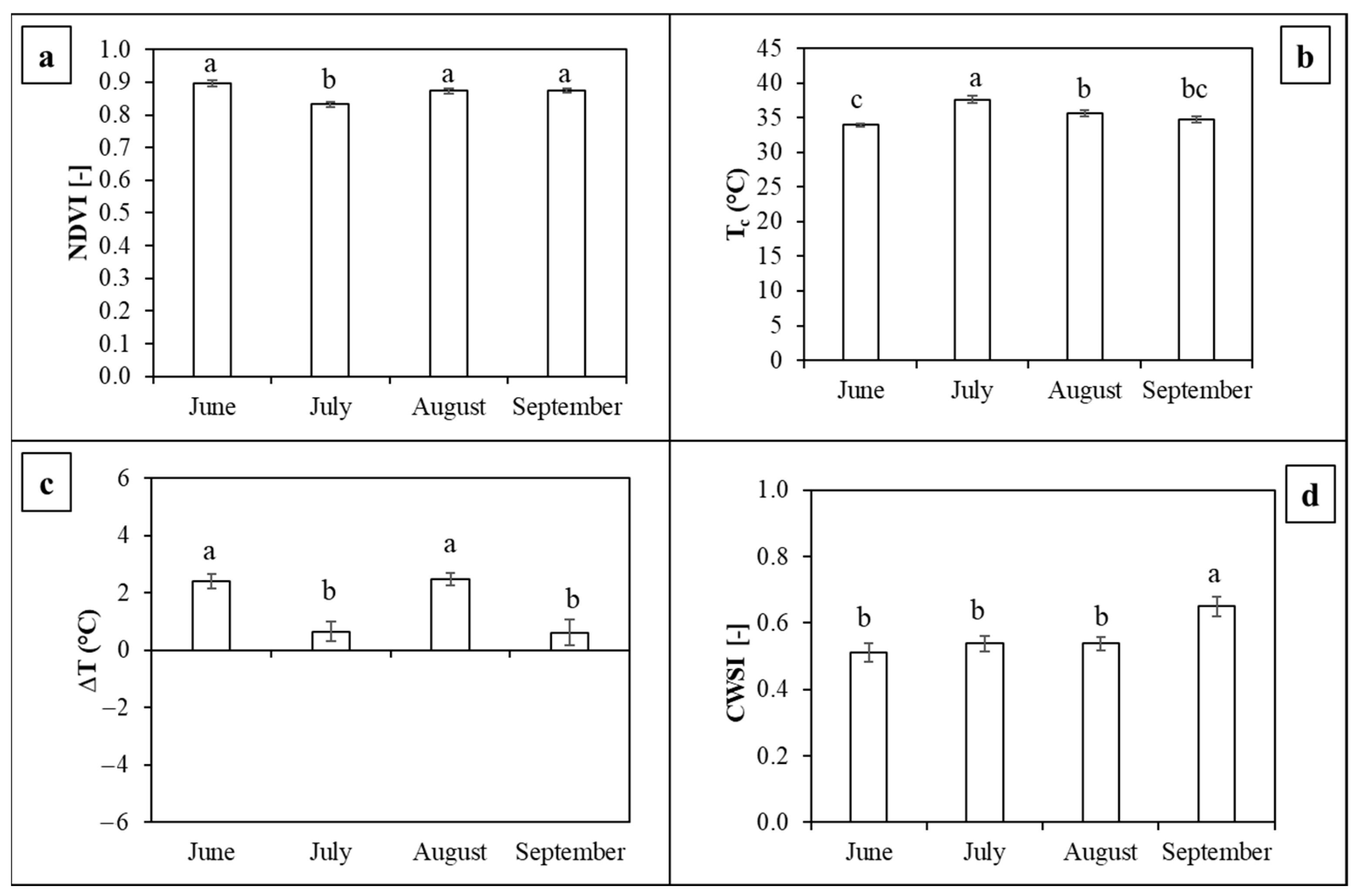

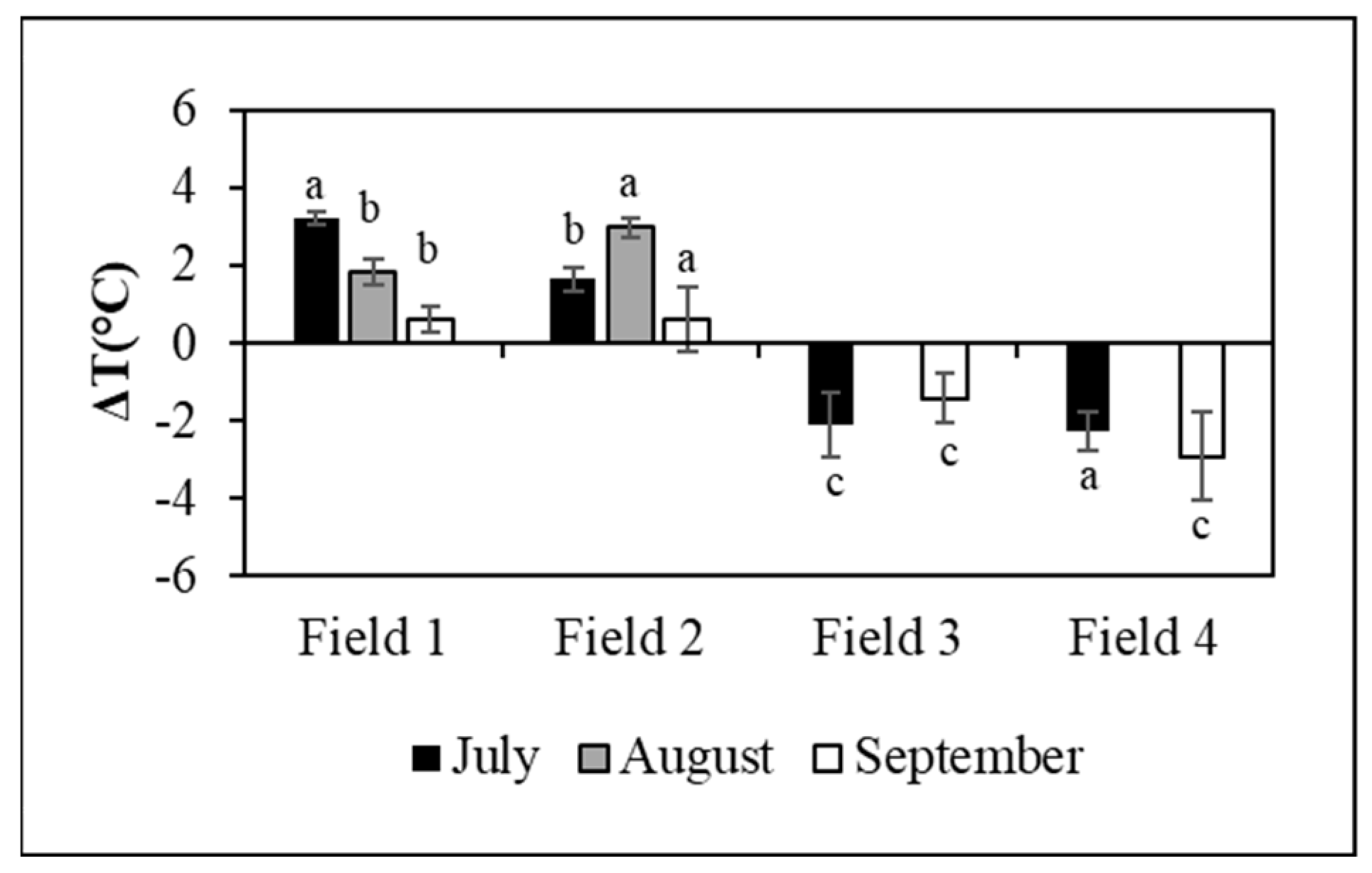

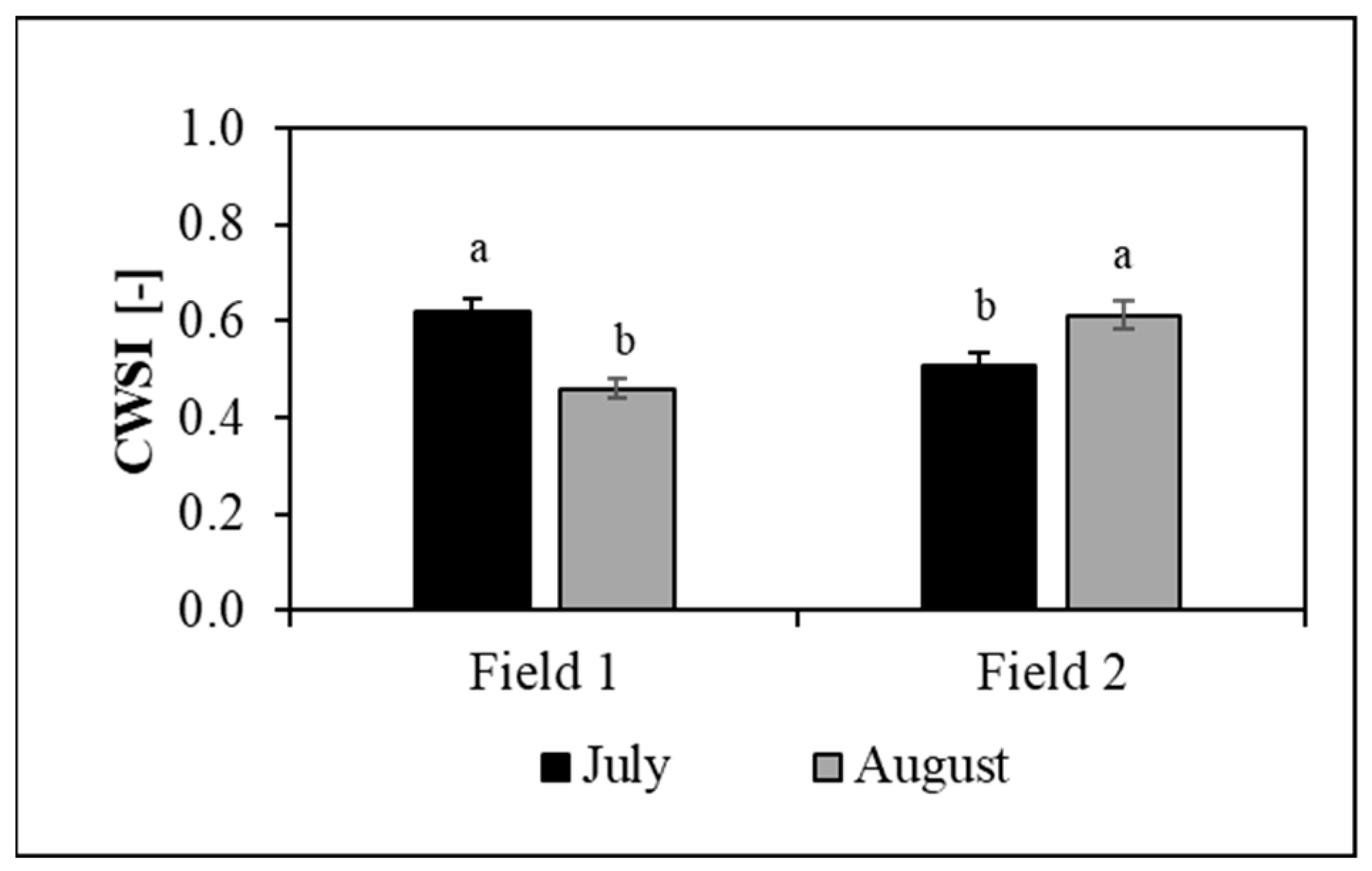

3. Results

3.1. Agrometeorological Data and Irrigation Volumes at the Study Site

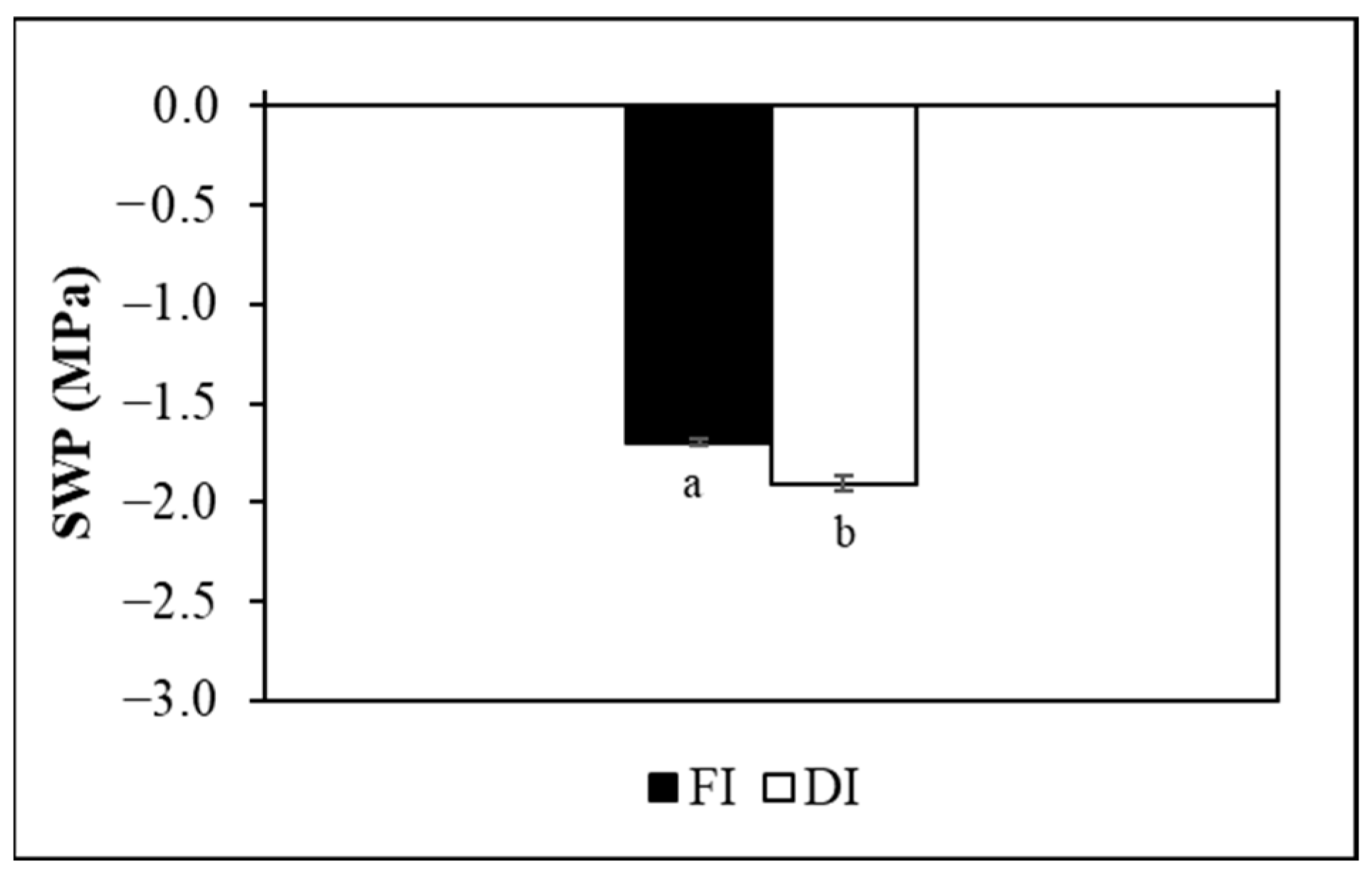

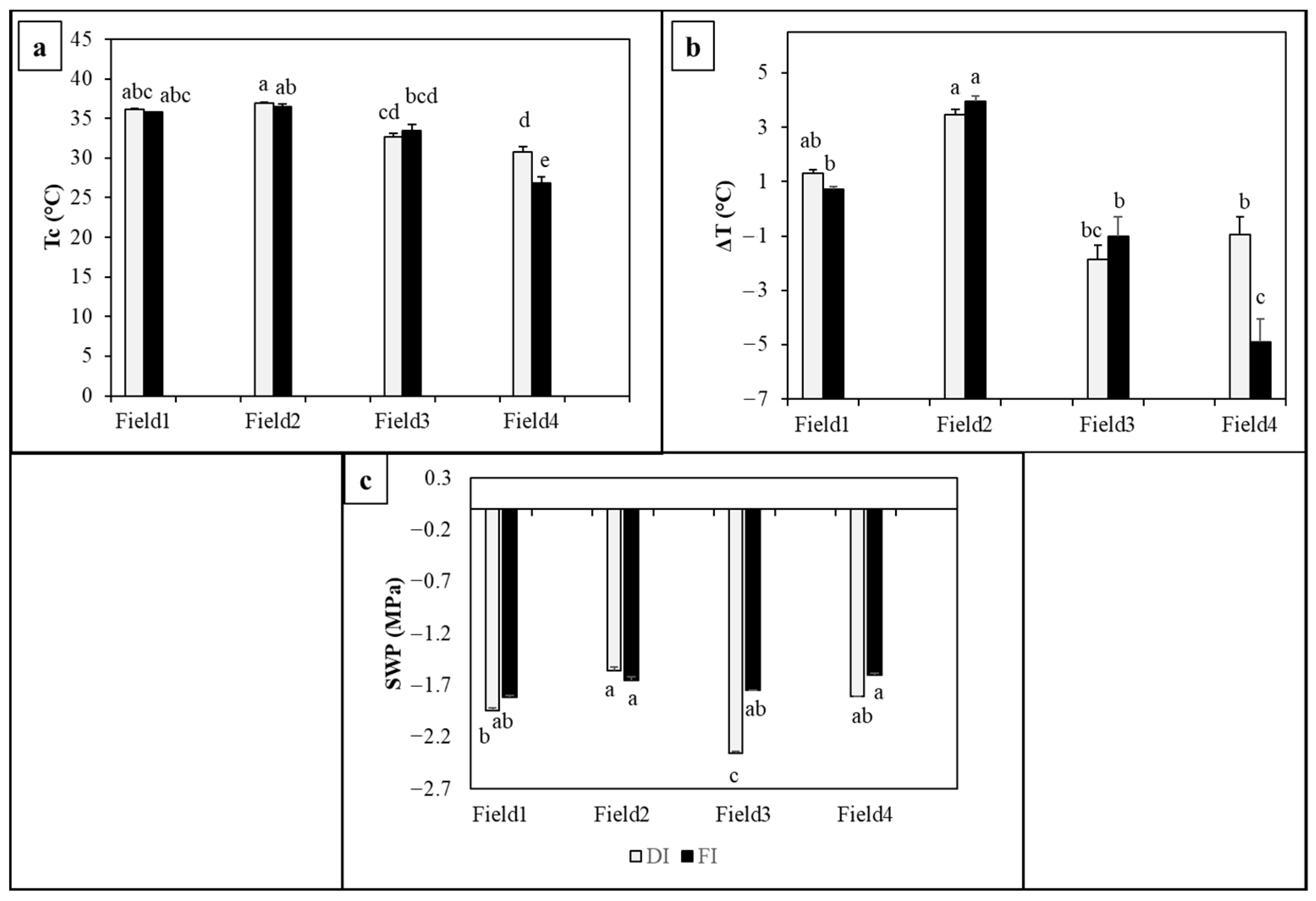

3.2. Effects of Deficit Irrigation Strategies on Citrus Water Status

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morante-Carballo, F.; Montalván-Burbano, N.; Quiñonez-Barzola, X.; Jaya-Montalvo, M.; Carrión-Mero, P. What Do We Know about Water Scarcity in Semi-Arid Zones? A Global Analysis and Research Trends. Water 2022, 14, 2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, J.; Paneque, P. Challenges for the Integration of Water Resource and Drought-Risk Management in Spain. Sustainability 2019, 11, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Serrano, S.M.; Miralles, D.G.; McDowell, N.; Brodribb, T.; Domínguez-Castro, F.; Leung, R.; Koppa, A. The Uncertain Role of Rising Atmospheric CO2 on Global Plant Transpiration. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2022, 230, 104055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnone, E.; Pumo, D.; Viola, F.; Noto, L.V.; La Loggia, G. Rainfall statistics changes in Sicily. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 17, 2449–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, F.; Liuzzo, L.; Noto, L.V.; Conti, F.; La Loggia, G. Spatial Distribution of Temperature Trends in Sicily. Int. J. Climatol. 2014, 34, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consoli, S.; Stagno, F.; Roccuzzo, G.; Cirelli, G.L.; Intrigliolo, F. Sustainable Management of Limited Water Resources in a Young Orange Orchard. Agric. Water Manag. 2014, 132, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consoli, S.; Stagno, F.; Vanella, D.; Boaga, J.; Cassiani, G.; Roccuzzo, G. Partial Root-Zone Drying Irrigation in Orange Orchards: Effects on Water Use and Crop Production Characteristics. Eur. J. Agron. 2017, 82, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriminna, R.; Angellotti, G.; Luque, R.; Pagliaro, M. The Citrus Economy in Sicily in the Early Bioeconomy Era: A Case Study for Bioeconomy practitioners. Biofuels Bioprod. Bioref. 2024, 18, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fares, A.; Bayabil, H.K.; Zekri, M.; Mattos, D., Jr.; Awal, R. Potential Climate Change Impacts on Citrus Water Requirement Major Producing Areas in the World. J. Water Clim. Chang. 2017, 8, 576–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sthowski, P.; Jagosz, B.; Rolbiecki, S.; Rolbiecki, R. Predictive Capacity of Rainfall Data to Estimate the Water Needs of Fruit Plants in Water Deficit Areas. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berríos, P.; Temnani, A.; Zapata-García, S.; Sánchez-Navarro, V.; Zornoza, R.; Pérez-Pastor, A. Effect of Deficit Irrigation and Mulching on the Agronomic and Physiological Response of Mandarin Trees as Strategies to Cope with Water Scarcity in a Semi-Arid Climate. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 324, 112572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanella, D.; Ferlito, F.; Torrisi, B.; Giuffrida, A.; Pappalardo, S.; Saitta, D.; Longo-Minnolo, G.; Consoli, S. Long-Term Monitoring of Deficit Irrigation Regimes on Citrus Orchards in Sicily. J. Agric. Eng. 2021, 52, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitta, D.; Consoli, S.; Ferlito, F.; Torrisi, B.; Allegra, M.; Longo-Minnolo, G.; Vanella, D. Adaptation of Citrus Orchards to Deficit Irrigation Strategies. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 247, 106734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capra, A.; Consoli, S.; Russo, A.; Scicolone, B. Integrated Agro-Economic Approach to Deficit Irrigation on Lettuce Crops in Sicily (Italy). J. Irrig. Drain. Eng. 2008, 134, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasque, M.; Martí, P.; Granero, B.; González-Altozano, P. Effects of Long-Term Summer Deficit Irrigation on ‘Navelina’ Citrus Trees. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 169, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Dugo, V.; Ruz, C.; Testi, L.; Orgaz, F.; Fereres, E. The Impact of Deficit Irrigation on Transpiration and Yield of Mandarin and Late Oranges. Irrig. Sci. 2018, 36, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.H.; Schurr, U.; Davies, W.J. Control of Stomatal Behavior by Abscisic-Acid Which Apparently Originates in the Roots. J. Exp. Bot. 1987, 38, 1174–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, W.J.; Hartung, W. The Nexus between Root Signals and Stomatal Control: New Insights from Partial Rootzone Drying. Plant Cell Environ. 2004, 27, 69–87. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, S.; Zhang, J. Controlled Alternate Partial Root-Zone Irrigation: Its Physiological Consequences and Impact on Water Use Efficiency. J. Exp. Bot. 2004, 55, 2437–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepaskhah, A.; Ahmadi, S.H. A Review on Partial Root-Zone Drying Irrigation. Int. J. Plant Prod. 2010, 4, 1735–6814. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Pérez, J.G.; Navarro, J.M.; Robles, J.M.; Dodd, I.C. Prolonged Drying Cycles Stimulate ABA accumulation in Citrus Macrophylla Seedlings Exposed to Partial Rootzone Drying. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 210, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rallo, G.; Paço, T.A.; Paredes, P.; Puig-Sirera, A.; Massai, R.; Provenzano, G.; Pereira, L.S. Updated Single and Dual Crop Coefficients for Tree and Vine Fruit Crops. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 250, 106645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.E.; Padilla-Díaz, C.M.; Martínez, G.; Fernández, A.; Pérez-Ruiz, M. Advanced Irrigation Scheduling Techniques: Using Sensors and Remote Sensing for Improving Water Use in Agriculture. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 240, 106270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholander, P.F.; Hammel, H.T.; Bradstreet, E.D.; Hemmingsen, E.A. Sap Pressure in Vascular Plants. Science 1965, 148, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.G.; Baker, W.L.; Peterson, C.J.; Peet, R.K. Factors Influencing Succession: Lessons from Large, Infrequent Natural Disturbances. Ecosystems 1998, 1, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Y.; Alchanatis, V.; Saranga, Y.; Rosenberg, O.; Sela, E.; Bosak, A.J.P.A. Mapping Water Status Based on Aerial Thermal Imagery: Comparison of Methodologies for Upscaling from a Single Leaf to Commercial Fields. Precis. Agric. 2017, 18, 801–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Zhang, H.; DeJonge, K.C.; Comas, L.H.; Gleason, S. Comparison of Three Crop Water Stress Index Models with Sap Flow Measurements in Maize. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 203, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruso, G.; Palai, G.; Gucci, R.; Priori, S. Remote and Proximal Sensing Techniques for Site-Specific Irrigation Management in the Olive Orchard. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darra, N.; Psomiadis, E.; Kasimati, A.; Anastasiou, A.; Anastasiou, E.; Fountas, S. Remote and Proximal Sensing-Derived Spectral Indices and Biophysical Variables for Spatial Variation Determination in Vineyards. Agronomy 2021, 11, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Gal, A.; Agam, N.; Alchanatis, V.; Cohen, Y.; Yermiyahu, U.; Zipori, I.; Presnov, E.; Sprintsin, M.; Dag, A. Evaluating Water Stress in Irrigated Olives: Correlation of Soil Water Status, Tree Water Status, and Thermal Imagery. Irrig. Sci. 2009, 27, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egea, G.; Padilla-Díaz, C.M.; Martínez, J.; Fernández, J.E.; Pérez-Ruiz, M. Use of Aerial Thermal Imaging to Assess Water Status Variability in Hedgerow Olive Orchards. Agric. Water Manag. 2016, 187, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Tejero, I.F.; Ortega-Arévalo, C.J.; Iglesias-Contreras, M.; Moreno, J.M.; Souza, L.; Tavira, S.C.; Durán-Zuazo, V.H. Assessing the Crop-Water Status in Almond (Prunus dulcis Mill.) Trees via Thermal Imaging Camera Connected to Smartphone. Sensors 2018, 18, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanco, V.; Willsea, N.; Campbell, T.; Howe, O.; Kalcsits, L. Combining Thermal Imaging and Soil Water Content Sensors to Assess Tree Water Status in Pear Trees. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1197437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, C.; Jiménez-Bello, M.A.; Castel, J.R.; Intrigliolo, D.S. Usefulness of Thermography for Plant Water Stress Detection in Citrus and Persimmon Trees. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2013, 168, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangus, D.L.; Sharda, A.; Zhang, N. Development and Evaluation of Thermal Infrared Imaging System for High Spatial and Temporal Resolution Crop Water Stress Monitoring of Corn within a Greenhouse. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2016, 121, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, M.; Alchanatis, V.; Cohen, Y.; Meron, M.; Tsipris, J.; Naor, A.; Ostrovsky, V.; Sprintsin, M.; Cohen, S. Use of Thermal and Visible Imagery for Estimating Crop Water Status of Irrigated Grapevine. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 827–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idso, S.B.; Jackson, R.D.; Reginato, R.J. Normalizing the Stress-Degree-Day Parameter for Environmental Variability. Agric. Meteorol. 1981, 24, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Dugo, V.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Fereres, E. Applicability and Limitations of Using the Crop Water Stress Index as an Indicator of Water Deficits in Citrus Orchards. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2014, 198, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi, S.; Zand-Parsa, S.; Niyogi, D. Assessing Crop Water Stress Index of Citrus Using In-Situ Measurements, Landsat, and Sentinel-2 Data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2021, 42, 1893–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, J.W.; Haas, R.H.; Schell, J.A.; Deering, D.W. Monitoring Vegetation Systems in the Great Plains with ERTS. NASA Spec. Publ. 1974, 351, 309. [Google Scholar]

- El-Hendawy, S.E.; Al-Suhaibani, N.; Alotaibi, M.; Hassan, W.; Elsayed, S.; Tahir, M.U.; Ahmed Ibrahim Mohamed, A.I.; Schmidhalter, U. Estimating growth and photosynthetic properties of wheat grown in simulated saline field conditions using hyperspectral reflectance sensing and multivariate analysis. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes de Oliveira, A.; Mameli, M.G.; Lo Cascio, M.; Sirca, C.; Satta, D. An index for user-friendly proximal detection of water requirements to optimized irrigation management in vineyards. Agronomy 2021, 11, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pou, A.; Diago, M.P.; Medrano, H.; Baluja, J.; Tardaguila, J. Validation of thermal indices for water status identification in grapevine. Agric. Water Manag. 2014, 134, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbatantuono, F.; Lopriore, G.; Tallou, A.; Brillante, L.; Ali, S.A.; Camposeo, S.; Vivaldi, G.A. Recent progress on grapevine water status assessment through remote and proximal sensing: A review. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 338, 113658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagos, P.; Van Liedekerke, M.; Borrelli, P.; Köninger, J.; Ballabio, C.; Orgiazzi, A.; Lugato, E.; Liakos, L.; Hervas, J.; Jones, A.; et al. European Soil Data Centre 2.0: Soil data and knowledge in support of the EU policies. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2022, 73, e13315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.G.; Pereira, L.S.; Raes, D.; Smith, M. Crop Evapotranspiration—Guidelines for Computing Crop Water Requirements. FAO Irrig. Drain. Pap. 1998, 56, 147–151. [Google Scholar]

- Flo, V.; Martínez-Vilalta, J.; Mencuccini, M.; Granda, V.; Anderegg, W.R.; Poyatos, R. Climate and functional traits jointly mediate tree water-use strategies. New Phytol. 2021, 231, 617–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakson, R.D.; Idso, S.B.; Reginato, R.J.; Pinter, P.J. Canopy Temperature as a Crop Water Stress Indicator. Water Resour. Res. 1981, 17, 1133–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Cuesta, J.M.; Ortuno, M.F.; Gonzalez-Dugo, V.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Parra, M.; Rubio-Asensio, J.S.; Intrigliolo, D.S. Assessment of peach trees water status and leaf gas exchange using on-the-ground versus airborne-based thermal imagery. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 267, 107628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappalardo, S.; Consoli, S.; Longo-Minnolo, G.; Vanella, D.; Longo, D.; Guarrera, S.; Ramírez-Cuesta, J.M. Performance Evaluation of a Low-Cost Thermal Camera for Citrus Water Status Estimation. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 288, 108489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitić, G.; Tagarakis, A.; Cselyuszka, N.; Panić, M.; Birgermajer, S.; Sakulski, D.; Matović, J. A New Low-Cost Portable Multispectral Optical Device for Precise Plant Status Assessment. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 162, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajak, P.; Ganguly, A.; Adhikary, S.; Bhattacharya, S. Internet of Things and smart sensors in agriculture: Scopes and challenges. J. Agric. Food Res. 2023, 14, 100776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Z.; Wang, J.; Liang, G.; Gao, P.; Li, J. Estimating Stomatal Conductance of Citrus under Water Stress Based on Multispectral Imagery and Machine Learning Methods. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1054587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhards, M.; Schlerf, M.; Mallick, K.; Udelhoven, T. Challenges and future perspectives of multi-/Hyperspectral thermal infrared remote sensing for crop water-stress detection: A review. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H.G. Irrigation scheduling: Advantages and pitfalls of plant-based methods. J. Exp. Bot. 2004, 55, 2427–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Tejero, I.F.; Hernández, A.; Padilla-Díaz, C.M.; Diaz-Espejo, A.; Fernandez, J.E. Assessing plant water status in a hedgerow olive orchard from thermography at plant level. Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 188, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, P.R.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.; Lam, S.; Whitty, M.A.; Skewes, M.A. The accuracy and Utility of a Low-Cost Thermal Camera and Smartphone-Based System to Assess Grapevine Water Status. Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 179, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Cuesta, J.M.; Consoli, S.; Longo, D.; Longo-Minnolo, G.; Intrigliolo, D.S.; Vanella, D. Influence of Short-Term Temperature Dynamics on Tree Orchards Energy Balance Fluxes. Precis. Agric. 2022, 23, 1394–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katimbo, A.; Rudnick, D.R.; DeJonge, K.C.; Lo, T.H.; Qiao, X.; Franz, T.E.; Duan, J. Crop Water Stress Index Computation Approaches and Their Sensitivity to Soil Water Dynamics. Agric. Water Manag. 2022, 266, 107575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irmak, S.; Haman, D.Z.; Bastug, R. Determination of Crop Water Stress Index for Irrigation Timing and Yield Estimation of Corn. Agron. J. 2000, 92, 1221–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camino, C.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; González-Dugo, V. Effects of Heterogeneity within Tree Crowns on Airborne-Quantified SIF and the CWSI as Indicators of Water Stress in the Context of Precision Agriculture. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conesa, M.R.; Conejero, W.; Vera, J.; Mira-García, A.B.; Ruiz-Sánchez, M.C. Impact of a DANA Event on the Thermal Response of Nectarine Trees. Plants 2023, 12, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Dugo, V.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J.; Fereres, E. Assessing the Impact of Measurement Errors in the Calculation of CWSI for Characterizing the Water Status of Several Crop Species. Irrig. Sci. 2022, 42, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo-Minnolo, G.; Vanella, D.; Consoli, S.; Intrigliolo, D.S.; Ramírez-Cuesta, J.M. Integrating Forecast Meteorological Data into the ArcDualKc Model for Estimating Spatially Distributed Evapotranspiration Rates of a Citrus Orchard. Agric. Water Manag. 2020, 231, 105967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velazquez-Chavez, L.J.; Daccache, A.; Mohamed, A.Z.; Centritto, M. Plant-based and remote sensing for water status monitoring of orchard crops: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 303, 109051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corak, N.K.; Otkin, J.A.; Ford, T.W.; Lowman, L.E.L. Unraveling Phenological and Stomatal Responses to Flash Drought and Implications for Water and Carbon Budgets. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2024, 28, 1827–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellvert, J.; Marsal, J.; Girona, J.; Gonzalez-Dugo, V.; Fereres, E.; Ustin, S.L.; Zarco-Tejada, P.J. Airborne thermal imagery to detect the seasonal evolution of crop water status in peach, nectarine and Saturn peach orchards. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglisi, I.; Nicolosi, E.; Vanella, D.; Lo Piero, A.R.; Stagno, F.; Saitta, D.; Roccuzzo, G.; Consoli, S.; Baglieri, A. Physiological and biochemical responses of orange trees to different deficit irrigation regimes. Plants 2019, 8, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seleiman, M.F.; Al-Suhaibani, N.; Ali, N.; Akmal, M.; Alotaibi, M.; Refay, Y.; Battaglia, M.L. Drought Stress Impacts on Plants and Different Approaches to Alleviate Its Adverse Effects. Plants 2021, 10, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortuño, M.F.; García-Orellana, Y.; Conejero, W.; Ruiz-Sánchez, M.C.; Alarcón, J.J.; Torrecillas, A. Stem and Leaf Water Potentials, Gas Exchange, Sap Flow, and Trunk Diameter Fluctuations for Detecting Water Stress in Lemon Trees. Trees 2006, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ID | Location | Latitude and Longitude (WGS84) | Elevation (m, a.s.l.) | Area (ha) | Cultivar and Rootstock | Spacing (m) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tree | Inter-Row | ||||||

| Field 1 | Lentini (SR) | 37°20′12.65″ N, 14°53′33.04″ E | 47 | 1.0 | Tarocco Sciara on Carrizo citrange | 4 | 6 |

| Field 2 | 37°20′23″ N, 14°53′34” E | 46 | 0.3 | Tarocco Meli on Carrizo and M5761, and Tarocco TDV on Carrizo and FAO 30591 | 4 | 6 | |

| Field 3 | Motta S. Anastasia (CT) | 37°28′47″ N, 14°57′9′’ E | 88 | 4.5 | Tarocco Ippolito and Tarocco Scirè on Carrizo | 5 | 2.5 |

| Field 4 | Misterbianco (CT) | 37°27′48″ N, 15°00′29″ E | 52 | 2.5 | Tarocco Meli on Carrizo | 3 | 5 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Optical resolution | 4000 × 3000 pixel |

| Wavelength | RGN (Red + Green + NIR): 550 nm/660 nm/850 nm |

| Lens optics | f2.8 aperture |

| Field of view | 87° (19 mm) |

| ISO setting | 50, 100, 200, 400, 800, 1600, Auto |

| Acquisition software | Mapir Camera Control (PC Windows) |

| Price (currently) | ~400 $ |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Optical resolution | 640 × 480 |

| Object temperature range | −20 °C to 400 °C |

| Spectral range | 8–14 μm |

| Accuracy | ±3 °C |

| Field of view (FOV) | 55° × 43° |

| Emissivity setting | 0.60–0.95 |

| Acquisition software | FLIR One (App for smartphone) |

| Price (currently) | ~450 $ |

| Fields | Irrigation Heights (mm) | Water Saving (%) * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Field 1 | FI | 445 | 30 |

| DI | 312 | ||

| Field 2 | FI | 270 | 12 |

| DI | 238 | ||

| Field 3 | FI | 155 | 15 |

| DI | 132 | ||

| Field 4 | FI | 267 | 57 |

| DI | 115 | ||

| Variable | Factor | F | p-Value | DF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDVI | ‘WR’ | 0.26 | 0.61 | 191 |

| Tc | 1.30 | 0.26 | 190 | |

| Tc − Tair (ΔT) | 0.67 | 0.42 | 187 | |

| CWSI | 0.83 | 0.36 | 144 | |

| SWP | 1.30 | 0.25 | 203 | |

| NDVI | ‘Month’ | 11.55 | 0.00 * | 191 |

| Tc | 12.79 | 0.00 * | 190 | |

| Tc − Tair (ΔT) | 8.89 | 0.00 * | 187 | |

| CWSI | 5.32 | 0.00 * | 144 | |

| SWP | 1.71 | 0.16 | 187 | |

| NDVI | ‘Field’ | 38.16 | 0.00* | 191 |

| Tc | 10.87 | 0.00 * | 190 | |

| Tc − Tair (ΔT) | 39.50 | 0.00 * | 187 | |

| CWSI | 0.59 | 0.62 | 156 | |

| SWP | 83.32 | 0.00 * | 187 |

| Month | Variable | Factor | F | p-Value | DF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| June | NDVI | ‘Field’ | 127.26 | 0.00 * | 42 |

| ‘WR’ | 0.45 | 0.50 | |||

| ‘Field’ × ‘WR’ | 0.14 | 0.94 | |||

| Tc | ‘Field’ | 24.68 | 0.00 * | 39 | |

| ‘WR’ | 4.21 | 0.05 | |||

| ‘Field’ × ‘WR’ | 2.33 | 0.11 | |||

| Tc − Tair | ‘Field’ | 0.49 | 0.62 | 42 | |

| ‘WR’ | 3.05 | 0.09 | |||

| ‘Field’ × ‘WR’ | 1.23 | 0.30 | |||

| CWSI | ‘Field’ | 1.11 | 0.30 | 34 | |

| ‘WR’ | 3.07 | 0.09 | |||

| ‘Field’ × ‘WR’ | 1.35 | 0.25 | |||

| SWP | ‘Field’ | 87.63 | 0.00 * | 51 | |

| ‘WR’ | 0.00 | 0.95 | |||

| ‘Field’ × ‘WR’ | 0.81 | 0.50 | |||

| July | NDVI | ‘Field’ | 51.52 | 0.00 * | 51 |

| ‘WR’ | 0.08 | 0.77 | |||

| ‘Field × ‘WR’ | 0.35 | 0.79 | |||

| Tc | ‘Field’ | 95.82 | 0.00* | 50 | |

| ‘WR’ | 1.36 | 0.25 | |||

| ‘Field’ × ‘WR’ | 1.71 | 0.18 | |||

| Tc − Tair | ‘Field’ | 34.81 | 0.00 * | 51 | |

| ‘WR’ | 1.56 | 0.22 | |||

| ‘Field’ × ‘WR’ | 1.35 | 0.27 | |||

| CWSI | ‘Field’ | 11.32 | 0.00 * | 35 | |

| ‘WR’ | 1.00 | 0.32 | |||

| ‘Field’ × ‘WR’ | 0.01 | 0.93 | |||

| SWP | ‘Field’ | 55.98 | 0.00 * | 51 | |

| ‘WR’ | 0.22 | 0.64 | |||

| ‘Field’ × ‘WR’ | 1.35 | 0.27 | |||

| August | NDVI | ‘Field’ | 136.51 | 0.00 * | 46 |

| ‘WR’ | 0.06 | 0.81 | |||

| ‘Field’ × ‘WR’ | 0.16 | 0.69 | |||

| Tc | ‘Field’ | 20.38 | 0.00 * | 47 | |

| ‘WR’ | 2.86 | 0.10 | |||

| ‘Field’ × ‘WR’ | 0.65 | 0.43 | |||

| Tc − Tair | ‘Field’ | 9.45 | 0.00 * | 40 | |

| ‘WR’ | 1.08 | 0.30 | |||

| ‘Field’ × ‘WR’ | 9.95 | 0.05 | |||

| CWSI | ‘Field’ | 18.77 | 0.00 * | 44 | |

| ‘WR’ | 1.94 | 0.17 | |||

| ‘Field’ × ‘WR’ | 0.12 | 0.73 | |||

| SWP | ‘Field’ | 89.75 | 0.00 * | 47 | |

| ‘WR’ | 0.26 | 0.61 | |||

| ‘Field’ × ‘WR’ | 2.07 | 0.16 | |||

| September | NDVI | ‘Field’ | 10.11 | 0.00 * | 49 |

| ‘WR’ | 0.04 | 0.84 | |||

| ‘Field’ × ‘WR’ | 1.66 | 0.19 | |||

| Tc | ‘Field’ | 46.08 | 0.00 * | 51 | |

| ‘WR’ | 3.31 | 0.08 | |||

| ‘Field’ × ‘WR’ | 2.98 | 0.04 * | |||

| Tc − Tair | ‘Field’ | 38.68 | 0.00 * | 43 | |

| ‘WR’ | 2.42 | 0.13 | |||

| ‘Field’ × ‘WR’ | 4.26 | 0.01 * | |||

| CWSI | ‘Field’ | 1.26 | 0.27 | 28 | |

| ‘WR’ | 0.29 | 0.59 | |||

| ‘Field’ × ‘WR’ | 0.51 | 0.48 | |||

| SWP | ‘Field’ | 15.35 | 0.00 * | 51 | |

| ‘WR’ | 16.47 | 0.00 * | |||

| ‘Field’ × ‘WR’ | 7.78 | 0.00 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Toscano, S.; Consoli, S.; Longo-Minnolo, G.; Guarrera, S.; Continella, A.; Modica, G.; Gentile, A.; Las Casas, G.; Barbagallo, S.; Vanella, D. Using Low-Cost Proximal Sensing Sensors for Detecting the Water Status of Deficit-Irrigated Orange Orchards in Mediterranean Climatic Conditions. Agronomy 2025, 15, 550. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15030550

Toscano S, Consoli S, Longo-Minnolo G, Guarrera S, Continella A, Modica G, Gentile A, Las Casas G, Barbagallo S, Vanella D. Using Low-Cost Proximal Sensing Sensors for Detecting the Water Status of Deficit-Irrigated Orange Orchards in Mediterranean Climatic Conditions. Agronomy. 2025; 15(3):550. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15030550

Chicago/Turabian StyleToscano, Sabrina, Simona Consoli, Giuseppe Longo-Minnolo, Serena Guarrera, Alberto Continella, Giulia Modica, Alessandra Gentile, Giuseppina Las Casas, Salvatore Barbagallo, and Daniela Vanella. 2025. "Using Low-Cost Proximal Sensing Sensors for Detecting the Water Status of Deficit-Irrigated Orange Orchards in Mediterranean Climatic Conditions" Agronomy 15, no. 3: 550. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15030550

APA StyleToscano, S., Consoli, S., Longo-Minnolo, G., Guarrera, S., Continella, A., Modica, G., Gentile, A., Las Casas, G., Barbagallo, S., & Vanella, D. (2025). Using Low-Cost Proximal Sensing Sensors for Detecting the Water Status of Deficit-Irrigated Orange Orchards in Mediterranean Climatic Conditions. Agronomy, 15(3), 550. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy15030550