Nutrient Management in Aquaponics: Comparison of Three Approaches for Cultivating Lettuce, Mint and Mushroom Herb

Abstract

1. Introduction

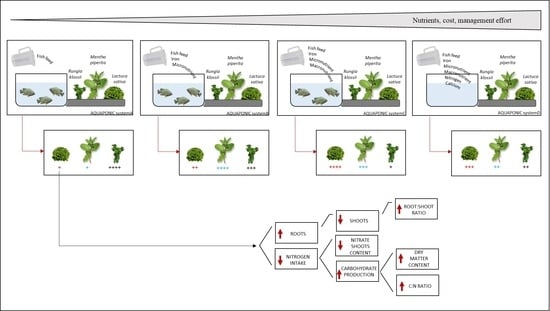

2. Results

2.1. Water Quality

2.2. Growth of Fish and Plants

2.3. Chlorophyll (CHL), Epidermal UV-Absorbance (FLV) and Nitrogen Balance Index (NBI)

2.4. Nitrate Levels in Plant Tissue

2.5. Dry Matter and CHN

2.6. Water Loss during Storage

3. Discussion

4. Material and Methods

4.1. System Design

4.2. Experimental Design

4.3. Sampling Plants and Fish

4.4. Assessing Plant Quality

4.5. Nitrate Levels in Leaf Tissue

4.6. Organic Matter and CHN-Elemental Analysis

4.7. Water Loss during Storage

4.8. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Diver, S.; Rinehart, L. Aquaponics—Integration of Hydroponics with Aquaculture; ATTRA—National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service: Fayetteville, AR, USA, 2010; 28p. [Google Scholar]

- Rakocy, J.E.; Losordo, T.M.; Masser, M.P. Recirculating Aquaculture Tank Production Systems. Integrating Fish and Plant Culture; SRAC Publication: Stoneville, MS, USA, 1992; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkie, M.P. Mechanisms of ammonia excretion across fish gills. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 1997, 1, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, S.J.; Moccia, R.D.; Durant, G.M. The chemical composition of settleable solid fish waste (manure) from commercial Rainbow Trout farms in Ontario, Canada. N. Am. J. Aquacult. 1999, 61, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, G.K.; Steinberg, D.K. Abundance, composition, and sinking rates of fish fecal pellets in the Santa Barbara Channel. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resh, H.M. Hydroponic Food Production: A Definitive Guidebook for the Advanced Home Gardener and the Commercial Hydroponic Grower; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Heeb, A.; Lundegårdh, B.; Ericsson, T.; Savage, G.P. Effects of nitrate-, ammonium-, and organic-nitrogen-based fertilizers on growth and yield of tomatoes. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2005, 168, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premuzic, Z.; Bargiela, M.; Garcia, A.; Rendina, A.; Iorio, A. Calcium, iron, potassium, phosphorus, and vitamin C content of organic and hydroponic tomatoes. HortScience 1998, 33, 255–257. [Google Scholar]

- Shinohara, M.; Aoyama, C.; Fujiwara, K.; Watanabe, A.; Ohmori, H.; Uehara, Y.; Takano, M. Microbial mineralization of organic nitrogen into nitrate to allow the use of organic fertilizer in hydroponics. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2011, 57, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkin, K.; Nichols, M.A. Organic hydroponics. Acta Hort. 2004, 648, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seawright, D.E.; Stickney, R.R.; Walker, R.B. Nutrient dynamics in integrated aquaculture–hydroponics systems. Aquaculture 1998, 160, 215–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakocy, J.E.; Masser, M.P.; Losordo, T.M. Recirculating Aquaculture Tank Production Systems: Aquaponics–Integrating Fish and Plant Culture; SRAC Publication: Stoneville, MS, USA, 2006; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Roosta, H.R. Comparison of the vegetative growth, eco-physiological characteristics and mineral nutrient content of basil plants in different irrigation ratios of hydroponic: Aquaponic solutions. J. Plant Nutr. 2014, 37, 1782–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmautz, Z.; Graber, A.; Mathis, A.; Griessler Bulc, T.; Junge, R. Tomato production in aquaponic system: Mass balance and nutrient recycling. In Aquaculture Europe 15; EAS (European Aquaculture Society): Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Available online: https://www.was.org/easonline/AbstractDetail.aspx?i=4340 (accessed on 15 October 2017).

- Ako, H.; Baker, A. Small-scale lettuce production with hydroponics or aquaponics. Sustain. Agric. 2009, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Goddek, S.; Delaide, B.; Mankasingh, U.; Ragnarsdottir, K.; Jijakli, H.; Thorarinsdottir, R. Challenges of sustainable and commercial aquaponics. Sustainability 2015, 7, 4199–4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakocy, J.E.; Bailey, D.S.; Shultz, K.A.; Cole, W.M. Evaluation of a commercial-scale aquaponic unit for the production of tilapia and lettuce. In Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Tilapia in Aquaculture, Orlando, FL, USA, 1 January 1997; pp. 603–612. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.G.; Gastaldi, C.; Siddiqi, M.Y.; Glass, A.D.M. Growth of a lettuce crop at low ambient nutrient concentrations: A strategy designed to limit the potential for eutrophication. J. Plant Nutr. 1997, 20, 1403–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BC Ministry of Agriculture. Environmental Guidelines for Greenhouse Growers in British Columbia; BC Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food, Resource Management Branch: Abbotsford, BC, Canada, 1994.

- Bittsanszky, A.; Uzinger, N.; Gyulai, G.; Mathis, A.; Junge, R.; Kotzen, B.; Komives, T. Nutrient supply of plants in aquaponic systems. Ecocycles 2016, 2, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, M.A.; Savidov, N.A. Aquaponics: A nutrient and water efficient production system. In Proceedings of the II International Symposium on Soilless Culture and Hydroponics, Puebla, Mexico, 15–19 May 2011; pp. 129–132. [Google Scholar]

- Cakmak, I.; Hengeler, C.; Marschner, H. Partitioning of shoot and root dry-matter and carbohydrates in bean plants suffering from phosphorus-, potassium- and magnesium-deficiency. J. Exp. Bot. 1994, 278, 1245–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, C.; Hammond, J.P.; White, P.J.; Verbruggen, N. How do plants respond to nutrient shortage by biomass allocation? Trends Plant Sci. 2006, 12, 610–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez, M.C.; Rubio, G. Root morphological traits related to phosphorus-uptake efficiency of soybean, sunflower, and maize. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2015, 5, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buwalda, F.; Warmenhoven, M. Growth-limiting phosphate nutrition suppresses nitrate accumulation in greenhouse lettuce. J. Exp. Bot. 1999, 335, 813–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Habermeyer, M.; Roth, A.; Guth, S.; Diel, P.; Engel, K.H.; Epe, B.; Fürst, P.; Heinz, V.; Humpf, H.U.; Joost, H.G.; et al. Nitrate and nitrite in the diet: How to assess their benefit and risk for human health. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015, 59, 106–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashworth, A.; Mitchell, K.; Blackwell, J.R.; Vanhatalo, A.; Jones, A.M. High-nitrate vegetable diet increases plasma nitrate and nitrite concentrations and reduces blood pressure in healthy women. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 14, 2669–2678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commission Regulation (EU) No 1258/2011 of 2 December 2011 Amending Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 as Regards Maximum Levels for Nitrates in Foodstuffs. Available online: https://www.fsai.ie/uploadedFiles/Reg1258_2011.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2017).

- Santamaria, P.; Elia, A.; Gonnella, M.; Parente, A.; Serio, F. Ways of reducing rocket salad nitrate content. Acta Hortic. 2001, 548, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, A.S.; Iqbal, M. Nitrate accumulation in plants, factors affecting the process, and human health implications. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2007, 27, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagnari, F.; Galieni, A.; Pisante, M. Shading and nitrogen management affect quality, safety and yield of greenhouse-grown leaf lettuce. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 192, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeschke, W.D.; Kirkby, E.A.; Peuke, A.D.; Pate, J.S.; Hartung, W. Effects of P deficiency on assimilation and transport of nitrate and phosphate in intact plants of castor bean (Ricinus communis L.). J. Exp. Bot. 1997, 48, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, C.C.; Marcelis, L.F.M.; Van Den Boogaard, R.; Kaiser, W.M.; Lambers, H. Interaction of nitrogen and phosphorus nutrition in determining growth. Plant Soil 2003, 248, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhaohui, W.; Shengxiu, L. Effects of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilization on plant growth and nitrate accumulation in vegetables. J. Plant Nutr. 2004, 3, 539–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, G.C.; Ehaliotis, C.D.; Kavvadias, V.A. Effect of organic and inorganic fertilizers applied during successive crop seasons on growth and nitrate accumulation in lettuce. Sci. Hortic. 2007, 111, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom-Zandstra, M. Nitrate accumulation in vegetables and its relationship to quality. Ann. Appl. Biol. 1989, 115, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pinheiro Henriques, A.R.; Marcelis, L.F.M. Regulation of growth at steady-state nitrogen nutrition in lettuce (Lactuca sativa, L.): Interactive effects of nitrogen and irradiance. Ann. Bot. 2000, 86, 1073–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Lim, L.I.; Qin, L. Growth irradiance effects on productivity, photosynthesis, nitrate accumulation and assimilation of aeroponically grown Brassica alboglabra. J. Plant Nutr. 2015, 7, 1022–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, B.D.; Pant, P.; Erban, A.; Huhman, D.; Kopka, J.; Scheible, W.R. Identification of primary and secondary metabolites with phosphorus status-dependent abundance in Arabidopsis, and of the transcription factor PHR1 as a major regulator of metabolic changes during phosphorus limitation. Plant Cell Environ. 2015, 38, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priestley, C.A. Bases for the expression of the results of chemical analyses of plant tissue. Ann. Bot. 1973, 37, 943–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, J.N.; Johansen, A.S.; Poulsen, N. Influence of growth conditions on the value of crisphead lettuce 1. Marketable and nutritional quality as affected by nitrogen supply, cultivar and plant age. Plant Food Hum. Nutr. 1994, 46, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, U.; Wiebe, H.-J. Relation between photosynthesis and nitrate content of lettuce cultivars. Sci. Hortic. 1992, 49, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aherne, S.A.; O’Brien, N.M. Dietary flavonols: Chemistry, food content, and metabolism. Nutrition 2002, 18, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, K. Flavonols and flavones in food plants: A review. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 1976, 11, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkel-Shirley, B. Biosynthesis of flavonoids and effects of stress. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2002, 5, 218–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaliora, A.C.; Batzaki, C.; Christea, M.G.; Kalogeropoulos, N. Nutritional evaluation and functional properties of traditional composite salad dishes. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 62, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, R.A.; Paiva, N.L. Stress-induced phenylpropanoid metabolism. Plant Cell 1995, 7, 1085–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alarcón-Flores, M.I.; Romero-González, R.; Vidal, J.L.M.; Frenich, A.G. Multiclass determination of phenolic compounds in different varieties of tomato and lettuce by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 1120–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, M.-M.; Carey, E.E.; Rajashekar, C.B. Environmental stresses induce health-promoting phytochemicals in lettuce. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2009, 47, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, G. Seed coating: A tool for stand establishment; a stimulus to seed quality. HortTechnology 1991, 1, 98–102. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, D. HydroBuddy: An Open Source Nutrient Calculator for Hydroponics and General Agriculture. v1.5. 2013. Available online: http://scienceinhydroponics.com (accessed on 23 May 2015).

- Cerovic, Z.G.; Ghozlen, N.B.; Milhade, C.; Obert, M.; Debuisson, S.; Moigne, M.L. Nondestructive diagnostic test for nitrogen nutrition of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) based on dualex leaf-clip measurements in the field. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 3669–3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantwell, M.; Reid, M.S. Postharvest physiology and handling of fresh culinary herbs. J. Herbs Spices Med. Plants 1993, 1, 93–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | n | A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NH4-N (mg L−1) | 3 | 0.15 | 0.15–1.05 | 0.11–0.15 | 0.03–0.06 |

| NO2-N (mg L−1) | 3 | 0.03 | 0.03–0.04 | 0.01–0.02 | 0.25–0.04 |

| pH | 10 | 5.1–6.9 | 5.0–7.3 | 5.0–6.5 | 5.9–7.4 |

| O2 (mgL−1) | 10 | 7.5–8.3 | 7.1–8.6 | 6.6–8.4 | 5.9–7.6 |

| EC (µS cm−1) | 10 | 760–1042 | 550–1099 | 1483–1858 | 1234–1622 |

| T in fish tank (°C) | 10 | 25.8–29.8 | 24.8–28.4 | 25.5–28.8 | - |

| Average T in root zone (°C) | >1000 | 23.5 | 23.9 | 23.2 | 22.9 |

| NO3-N (mg L−1) | 84 | 62 | 82 | 63 | |

| PO4-P (mg L−1) | 3.5 | 1.9 | 28 | 28 | |

| K (mg L−1) | 48 | 35 | 146 | 123 | |

| Fe (mg L−1) | 0.1 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 2.3 | |

| Ca (mg L−1) | 90 | 74 | 74 | 117 | |

| Mg (mg L−1) | 15 | 11 | 32 | 35 |

| Date/Duration | Parameters | Tank A | Tank B | Tank C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 May 2015 | Number of fish | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Total weight (kg) | 12.40 | 10.82 | 11.31 | |

| Average weight per fish (kg) | 0.248 | 0.216 | 0.226 | |

| 30 June 2015 | Number | 49 | 50 | 50 |

| Total weight (kg) | 24.11 | 21.03 | 24.20 | |

| Average weight per fish (kg) | 0.492 | 0.421 | 0.484 | |

| 57 days | Average weight gain per fish (kg) | 0.244 | 0.205 | 0.258 |

| Total fish biomass produced (kg) | 11.96 | 10.25 | 12.90 | |

| Specific growth rate (%/day) | 1.20 | 1.17 | 1.33 | |

| Feed conversion ratio (FCR) | 1.25 | 1.49 | 1.16 |

| Production Parameters | Lactuca sativa | Mentha piperita | Rungia klossii | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | A | B | C | D | A | B | C | D | |

| Total No. of plants | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 |

| No. of unsellable plants | 1 | / | / | / | 6 | / | / | / | / | / | / | / |

| No. of plants harvested | 35 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 66 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 | 72 |

| Total biomass (fresh) kg | 9.2 | 10.6 | 13.5 | 12.4 | 7.7 | 11.6 | 10.5 | 9.9 | 1.31 | 1.25 | 0.76 | 0.98 |

| Shoots (fresh) kg | 8.0 | 9.8 | 12.3 | 11.3 | 5.7 | 9.5 | 9.0 | 8.7 | 0.67 | 0.66 | 0.43 | 0.53 |

| Roots (fresh) kg | 1.2 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 0.64 | 0.58 | 0.33 | 0.44 |

| Average shoot weight g | 222.0 | 272.4 | 340.5 | 313.6 | 78.7 | 132.4 | 124.3 | 120.3 | 9.32 | 9.20 | 5.97 | 7.39 |

| Production (shoot) kg m−2 | 4.00 | 4.90 | 6.13 | 5.65 | 3.07 | 4.77 | 4.48 | 4.33 | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.21 | 0.27 |

| relative production % | 65 | 80 | 100 | 92 | 59 | 100 | 94 | 91 | 100 | 100 | 64 | 79 |

| Elements | Source | Product Name & Supplier | Unit | A | B | C | D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (all) | Fish feed | Tilapia Vegi 4.5 mm Hokovit, CH | kg | 9.20 | 9.74 | 9.50 | 0 |

| Zn, B, Mn, Mo, Cu | Micronutrient solution | Multi Micro Mix Ökohum, Langrickenbach, Switzerland | g | 0 | 242 | 242 | 32.9 |

| Fe | Iron DTPA solution | SARL Plantin, France | g | 0 | 558 | 478 | 66.8 |

| P, K | Monopotassium phosphate, KH2PO4 | Krista™-MKP Yara GmbH & Co. KG, Dülmen, Germany | g | 0 | 0 | 1401 | 209 |

| Mg, S | Magnesium sulfate Heptahydrate (MgSO4·7H2O) | Bittersalz, rein technisch K + S KALI GmbH, Kassel, Germany | g | 0 | 0 | 1818 | 228 |

| K, S | Potassium sulfate, K2SO4 | SOP 100% soluble Yara GmbH & Co. KG, D | g | 0 | 0 | 2551 | 353 |

| NO3, Ca | Calcium nitrate, CaNO3 | YaraLiva™ CALCINIT™ Yara GmbH & Co. KG, D | g | 0 | 0 | 0 | 317 |

| KOH | KOH | KOH ≥85 %, Carl Roth GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany | g | 250 | 200 | 950 | 0 |

| Nitric acid | HNO3 (16%) | Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) (FLUKA) | mL | 0 | 0 | 0 | 350 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nozzi, V.; Graber, A.; Schmautz, Z.; Mathis, A.; Junge, R. Nutrient Management in Aquaponics: Comparison of Three Approaches for Cultivating Lettuce, Mint and Mushroom Herb. Agronomy 2018, 8, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy8030027

Nozzi V, Graber A, Schmautz Z, Mathis A, Junge R. Nutrient Management in Aquaponics: Comparison of Three Approaches for Cultivating Lettuce, Mint and Mushroom Herb. Agronomy. 2018; 8(3):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy8030027

Chicago/Turabian StyleNozzi, Valentina, Andreas Graber, Zala Schmautz, Alex Mathis, and Ranka Junge. 2018. "Nutrient Management in Aquaponics: Comparison of Three Approaches for Cultivating Lettuce, Mint and Mushroom Herb" Agronomy 8, no. 3: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy8030027

APA StyleNozzi, V., Graber, A., Schmautz, Z., Mathis, A., & Junge, R. (2018). Nutrient Management in Aquaponics: Comparison of Three Approaches for Cultivating Lettuce, Mint and Mushroom Herb. Agronomy, 8(3), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy8030027