Development of Dementia in Type 2 Diabetes Patients: Mechanisms of Insulin Resistance and Antidiabetic Drug Development

Abstract

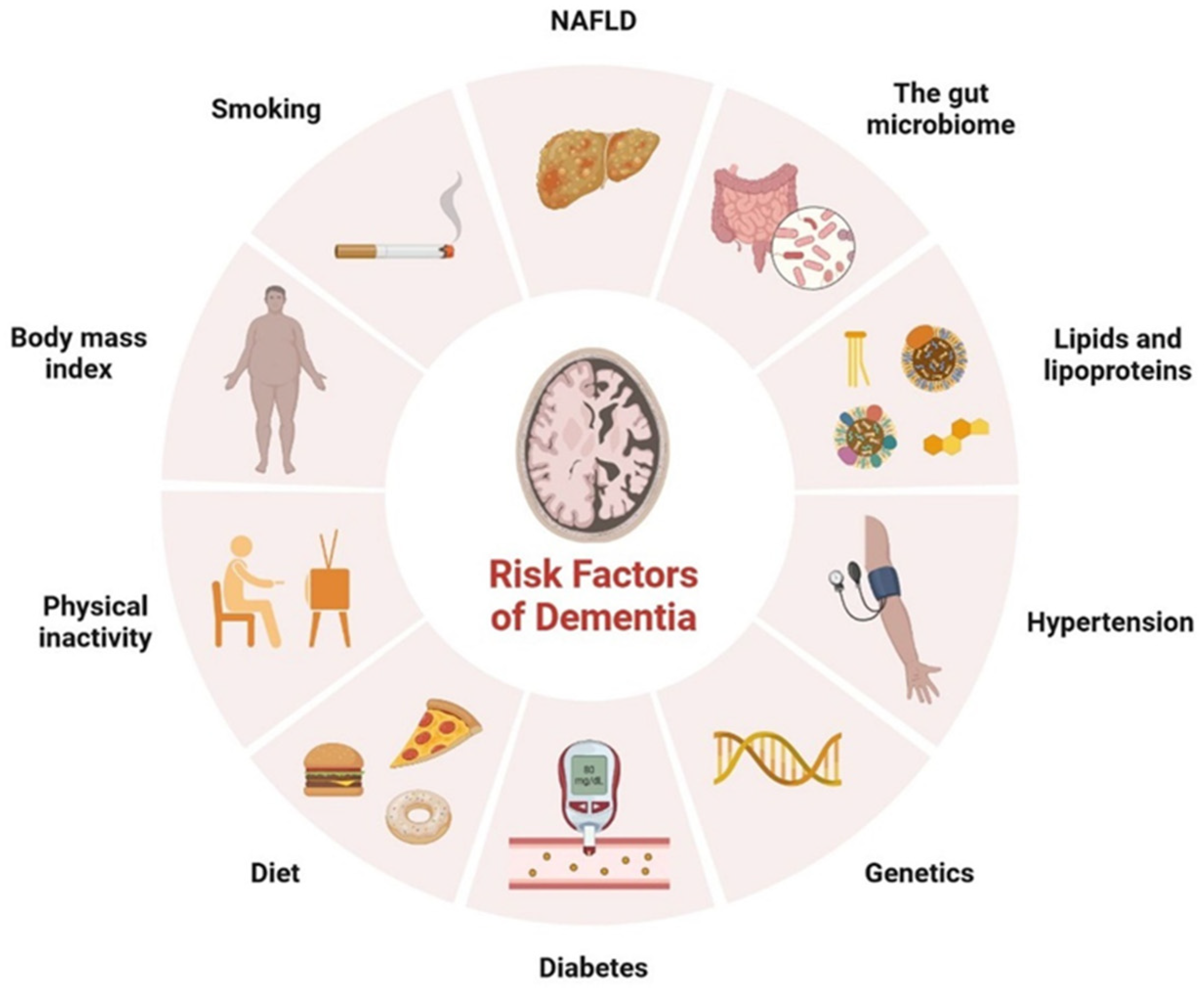

:1. Introduction

2. T2DM and Dementia

2.1. The Glucose Transporter’s Function in Cognition

2.2. Insulin Signaling and Neuro-Complications

2.3. Relationship between Insulin Receptor m-TOR Pathway

2.4. Development of Dementia due to Genetic Modifications

2.5. Progression of Dementia due to Dopamine Dysregulation in Substantia Nigra

2.6. Neuronal Apoptosis in Dementia

2.7. Significance of Ketone Bodies in Diabetes-Related Dementia

2.8. The Function of Mitochondria in Diabetes-Related Cognitive Impairment

2.9. Progressive Dementia Due to Microglial Overactivation

3. Antidiabetic Drug Development

3.1. Glucose–Sodium Co-transporter 2

3.2. Pioglitazone

3.3. Rosiglitazone

3.4. Metformin

3.5. Thiazolidinediones

3.6. GLP-1-Based Therapies

3.7. GLP-1 Analogs

3.8. Liraglutide

3.9. Dulaglutide and Lisisenatide

3.10. New GLP-1 Analogs

3.11. DPP-4 Inhibitors

3.12. Linagliptin A

3.13. Alogliptin

3.14. Vildagliptin

3.15. Sitagliptin

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chatterjee, S.; Khunti, K.; Davies, M.J. Type 2 Diabetes. Lancet 2017, 389, 2239–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, E.L.; Callaghan, B.C.; Pop-Busui, R.; Zochodne, D.W.; Wright, D.E.; Bennett, D.L.; Bril, V.; Russell, J.W.; Viswanathan, V. Diabetic Neuropathy. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2019, 5, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, K.S.; Sarma, R.H. Delineation of the Intimate Details of the Backbone Conformation of Pyridine Nucleotide Coenzymes in Aqueous Solution. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1975, 66, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomic, D.; Shaw, J.E.; Magliano, D.J. The Burden and Risks of Emerging Complications of Diabetes Mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2022, 18, 525–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunn, F.; Goodman, C.; Reece Jones, P.; Russell, B.; Trivedi, D.; Sinclair, A.; Bayer, A.; Rait, G.; Rycroft-Malone, J.; Burton, C. What Works for Whom in the Management of Diabetes in People Living with Dementia: A Realist Review. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomassen, J.Q.; Tolstrup, J.S.; Benn, M.; Frikke-Schmidt, R. Type-2 Diabetes and Risk of Dementia: Observational and Mendelian Randomisation Studies in 1 Million Individuals. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, e118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lyu, F.; Wu, D.; Wei, C.; Wu, A. Vascular Cognitive Impairment and Dementia in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Overview. Life Sci. 2020, 254, 117771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNay, E.C.; Pearson-Leary, J. GluT4: A Central Player in Hippocampal Memory and Brain Insulin Resistance. Exp. Neurol. 2020, 323, 113076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M.; Wang, P. Role of Insulin Receptor Substance-1 Modulating PI3K/Akt Insulin Signaling Pathway in Alzheimer’s Disease. 3 Biotech 2021, 11, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monti, G.; Gomes Moreira, D.; Richner, M.; Mutsaers, H.A.M.; Ferreira, N.; Jan, A. GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in Neurodegeneration: Neurovascular Unit in the Spotlight. Cells 2022, 11, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Qiang, Q.; Li, N.; Feng, P.; Wei, W.; Hölscher, C. Neuroprotective Mechanisms of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1-Based Therapies in Ischemic Stroke: An Update Based on Preclinical Research. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 844697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chau, A.C.M.; Cheung, E.Y.W.; Chan, K.H.; Chow, W.S.; Shea, Y.F.; Chiu, P.K.C.; Mak, H.K.F. Impaired Cerebral Blood Flow in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus—A Comparative Study with Subjective Cognitive Decline, Vascular Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease Subjects. NeuroImage Clin. 2020, 27, 102302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehtewish, H.; Arredouani, A.; El-Agnaf, O. Diagnostic, Prognostic, and Mechanistic Biomarkers of Diabetes Mellitus-Associated Cognitive Decline. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janson, J.; Laedtke, T.; Parisi, J.E.; O’Brien, P.; Petersen, R.C.; Butler, P.C. Increased Risk of Type 2 Diabetes in Alzheimer Disease. Diabetes 2004, 53, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Huang, C.-C.; Chung, C.-M.; Leu, H.-B.; Lin, L.-Y.; Chiu, C.-C.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Chiang, C.-H.; Huang, P.-H.; Chen, T.-J.; Lin, S.-J.; et al. Diabetes Mellitus and the Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biessels, G.J.; Staekenborg, S.; Brunner, E.; Brayne, C.; Scheltens, P. Risk of Dementia in Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review. Lancet Neurol. 2006, 5, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biessels, G.J.; Despa, F. Cognitive Decline and Dementia in Diabetes Mellitus: Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 591–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, E.; Steinmetz, J.D.; Vollset, S.E.; Fukutaki, K.; Chalek, J.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdoli, A.; Abualhasan, A.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.; Akram, T.T.; et al. Estimation of the Global Prevalence of Dementia in 2019 and Forecasted Prevalence in 2050: An Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e105–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ott, A.; Stolk, R.P.; van Harskamp, F.; Pols, H.A.P.; Hofman, A.; Breteler, M.M.B. Diabetes Mellitus and the Risk of Dementia: The Rotterdam Study. Neurology 1999, 53, 1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKnight, C.; Rockwood, K.; Awalt, E.; McDowell, I. Diabetes Mellitus and the Risk of Dementia, Alzheimer’s Disease and Vascular Cognitive Impairment in the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2002, 14, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craft, S.; Peskind, E.; Schwartz, M.W.; Schellenberg, G.D.; Raskind, M.; Porte, D. Cerebrospinal Fluid and Plasma Insulin Levels in Alzheimer’s Disease: Relationship to Severity of Dementia and Apolipoprotein E Genotype. Neurology 1998, 50, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.L.; Qiu, C.X.; Wahlin, A.; Winblad, B.; Fratiglioni, L. Diabetes Mellitus and Risk of Dementia in the Kungsholmen Project: A 6-Year Follow-up Study. Neurology 2004, 63, 1181–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnaider Beeri, M.; Goldbourt, U.; Silverman, J.M.; Noy, S.; Schmeidler, J.; Ravona-Springer, R.; Sverdlick, A.; Davidson, M. Diabetes Mellitus in Midlife and the Risk of Dementia Three Decades Later. Neurology 2004, 63, 1902–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronnemaa, E.; Zethelius, B.; Sundelof, J.; Sundstrom, J.; Degerman-Gunnarsson, M.; Berne, C.; Lannfelt, L.; Kilander, L. Impaired Insulin Secretion Increases the Risk of Alzheimer Disease. Neurology 2008, 71, 1065–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Z.; Tian, H.; Lam, K.S.L.; Lin, S.; Hoo, R.C.L.; Konishi, M.; Itoh, N.; Wang, Y.; Bornstein, S.R.; Xu, A.; et al. Adiponectin Mediates the Metabolic Effects of FGF21 on Glucose Homeostasis and Insulin Sensitivity in Mice. Cell Metab. 2013, 17, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mehta, H.B.; Mehta, V.; Goodwin, J.S. Association of Hypoglycemia with Subsequent Dementia in Older Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2016, 72, 1110–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cheng, G.; Huang, C.; Deng, H.; Wang, H. Diabetes as a Risk Factor for Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Studies: Diabetes and Cognitive Function. Intern. Med. J. 2012, 42, 484–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feinkohl, I.; Aung, P.P.; Keller, M.; Robertson, C.M.; Morling, J.R.; McLachlan, S.; Deary, I.J.; Frier, B.M.; Strachan, M.W.J.; Price, J.F.; et al. Severe Hypoglycemia and Cognitive Decline in Older People with Type 2 Diabetes: The Edinburgh Type 2 Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care 2014, 37, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Smolina, K.; Wotton, C.J.; Goldacre, M.J. Risk of Dementia in Patients Hospitalised with Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes in England, 1998–2011: A Retrospective National Record Linkage Cohort Study. Diabetologia 2015, 58, 942–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Matsuzaki, T.; Sasaki, K.; Tanizaki, Y.; Hata, J.; Fujimi, K.; Matsui, Y.; Sekita, A.; Suzuki, S.O.; Kanba, S.; Kiyohara, Y.; et al. Insulin Resistance Is Associated with the Pathology of Alzheimer Disease: The Hisayama Study. Neurology 2010, 75, 764–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, K.; DeSilva, S.; Abbruscato, T. The Role of Glucose Transporters in Brain Disease: Diabetes and Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 12629–12655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vulturar, R.; Chiș, A.; Pintilie, S.; Farcaș, I.M.; Botezatu, A.; Login, C.C.; Sitar-Taut, A.-V.; Orasan, O.H.; Stan, A.; Lazea, C.; et al. One Molecule for Mental Nourishment and More: Glucose Transporter Type 1—Biology and Deficiency Syndrome. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, G.D. Structure, Function and Regulation of Mammalian Glucose Transporters of the SLC2 Family. Pflugers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2020, 472, 1155–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koepsell, H. Glucose Transporters in Brain in Health and Disease. Pflugers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2020, 472, 1299–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frazier, H.N.; Ghoweri, A.O.; Anderson, K.L.; Lin, R.-L.; Popa, G.J.; Mendenhall, M.D.; Reagan, L.P.; Craven, R.J.; Thibault, O. Elevating Insulin Signaling Using a Constitutively Active Insulin Receptor Increases Glucose Metabolism and Expression of GLUT3 in Hippocampal Neurons. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurcovicova, J. Glucose Transport in Brain—Effect of Inflammation. Endocr. Regul. 2014, 48, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, S.M.; Barnes, K.; de Marco, M.; Shaw, P.J.; Ferraiuolo, L.; Blackburn, D.J.; Venneri, A.; Mortiboys, H. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Biomarker of the Future? Biomedicines 2021, 9, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oddo, S. The Role of MTOR Signaling in Alzheimer Disease. Front. Biosci. 2012, S4, 941–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shaughness, M.; Acs, D.; Brabazon, F.; Hockenbury, N.; Byrnes, K.R. Role of Insulin in Neurotrauma and Neurodegeneration: A Review. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 547175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, B.; Gong, C.-X. Deregulation of Brain Insulin Signaling in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurosci. Bull. 2014, 30, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobday, A.L.; Parmar, M.S. The Link Between Diabetes Mellitus and Tau Hyperphosphorylation: Implications for Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cureus 2021, 13, e18362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heras-Sandoval, D.; Avila-Muñoz, E.; Arias, C. The Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase/MTor Pathway as a Therapeutic Target for Brain Aging and Neurodegeneration. Pharmaceuticals 2011, 4, 1070–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, L.; Xie, A. The Role of Insulin/IGF-1/PI3K/Akt/GSK3β Signaling in Parkinson’s Disease Dementia. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hu, Z.; Jiao, R.; Wang, P.; Zhu, Y.; Zhao, J.; de Jager, P.; Bennett, D.A.; Jin, L.; Xiong, M. Shared Causal Paths Underlying Alzheimer’s Dementia and Type 2 Diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Canchi, S.; Raao, B.; Masliah, D.; Rosenthal, S.B.; Sasik, R.; Fisch, K.M.; de Jager, P.L.; Bennett, D.A.; Rissman, R.A. Integrating Gene and Protein Expression Reveals Perturbed Functional Networks in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell Rep. 2019, 28, 1103–1116.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Campoy, O.; Lladó, A.; Bosch, B.; Ferrer, M.; Pérez-Millan, A.; Vergara, M.; Molina-Porcel, L.; Fort-Aznar, L.; Gonzalo, R.; Moreno-Izco, F.; et al. Differential Gene Expression in Sporadic and Genetic Forms of Alzheimer’s Disease and Frontotemporal Dementia in Brain Tissue and Lymphoblastoid Cell Lines. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 59, 6411–6428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lopez, O.L.; Sweet, R.A.; Becker, J.T.; DeKosky, S.T.; Barmada, M.M.; Demirci, F.Y.; Kamboh, M.I. Genetic Determinants of Disease Progression in Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2014, 43, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, C.-C.; Kanekiyo, T.; Xu, H.; Bu, G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer Disease: Risk, Mechanisms and Therapy. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2013, 9, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dove, A.; Shang, Y.; Xu, W.; Grande, G.; Laukka, E.J.; Fratiglioni, L.; Marseglia, A. The Impact of Diabetes on Cognitive Impairment and Its Progression to Dementia. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2021, 17, 1769–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottero, V.; Potashkin, J.A. Meta-Analysis of Gene Expression Changes in the Blood of Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease Dementia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newcombe, E.A.; Camats-Perna, J.; Silva, M.L.; Valmas, N.; Huat, T.J.; Medeiros, R. Inflammation: The Link between Comorbidities, Genetics, and Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Neuroinflammation 2018, 15, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hiltunen, M.; Khandelwal, V.K.M.; Yaluri, N.; Tiilikainen, T.; Tusa, M.; Koivisto, H.; Krzisch, M.; Vepsäläinen, S.; Mäkinen, P.; Kemppainen, S.; et al. Contribution of Genetic and Dietary Insulin Resistance to Alzheimer Phenotype in APP/PS1 Transgenic Mice. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2012, 16, 1206–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, A.I.; Moreira, P.I.; Oliveira, C.R. Insulin in Central Nervous System: More than Just a Peripheral Hormone. J. Aging Res. 2012, 2012, 384017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Iannotti, F.A.; Vitale, R.M. The Endocannabinoid System and PPARs: Focus on Their Signaling Crosstalk, Action and Transcriptional Regulation. Cells 2021, 10, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.-R.; Huang, J.-B.; Yang, S.-L.; Hong, F.-F. Role of Cholinergic Signaling in Alzheimer’s Disease. Molecules 2022, 27, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Mello, N.P.; Orellana, A.M.; Mazucanti, C.H.; de Morais Lima, G.; Scavone, C.; Kawamoto, E.M. Insulin and Autophagy in Neurodegeneration. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Al-Samerria, S.; Radovick, S. The Role of Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1) in the Control of Neuroendocrine Regulation of Growth. Cells 2021, 10, 2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Kusky, J.; Ye, P. Neurodevelopmental Effects of Insulin-like Growth Factor Signaling. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2012, 33, 230–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jensen, N.J.; Wodschow, H.Z.; Nilsson, M.; Rungby, J. Effects of Ketone Bodies on Brain Metabolism and Function in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.Y.; Kim, O.Y.; Song, J. Role of Ketone Bodies in Diabetes-Induced Dementia: Sirtuins, Insulin Resistance, Synaptic Plasticity, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, and Neurotransmitter. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 774–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juárez Olguín, H.; Calderón Guzmán, D.; Hernández García, E.; Barragán Mejía, G. The Role of Dopamine and Its Dysfunction as a Consequence of Oxidative Stress. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 9730467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, Y.-K.; Kim, O.Y.; Song, J. Alleviation of Depression by Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 Through the Regulation of Neuroinflammation, Neurotransmitters, Neurogenesis, and Synaptic Function. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath, T.; Baskerville, R.; Rogero, M.; Castell, L. Emerging Evidence for the Widespread Role of Glutamatergic Dysfunction in Neuropsychiatric Diseases. Nutrients 2022, 14, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilliraj, L.N.; Schiuma, G.; Lara, D.; Strazzabosco, G.; Clement, J.; Giovannini, P.; Trapella, C.; Narducci, M.; Rizzo, R. The Evolution of Ketosis: Potential Impact on Clinical Conditions. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galizzi, G.; Di Carlo, M. Insulin and Its Key Role for Mitochondrial Function/Dysfunction and Quality Control: A Shared Link between Dysmetabolism and Neurodegeneration. Biology 2022, 11, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Felice, F.G.; Ferreira, S.T. Inflammation, Defective Insulin Signaling, and Mitochondrial Dysfunction as Common Molecular Denominators Connecting Type 2 Diabetes to Alzheimer Disease. Diabetes 2014, 63, 2262–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shan, Z.; Fa, W.H.; Tian, C.R.; Yuan, C.S.; Jie, N. Mitophagy and Mitochondrial Dynamics in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Treatment. Aging 2022, 14, 2902–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potenza, M.A.; Sgarra, L.; Desantis, V.; Nacci, C.; Montagnani, M. Diabetes and Alzheimer’s Disease: Might Mitochondrial Dysfunction Help Deciphering the Common Path? Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.-S.; Ning, J.-Q.; Chen, Z.-Y.; Li, W.-J.; Zhou, R.-L.; Yan, R.-Y.; Chen, M.-J.; Ding, L.-L. The Role of Mitochondrial Quality Control in Cognitive Dysfunction in Diabetes. Neurochem. Res. 2022, 47, 2158–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Chowdhury, K.; Kumar, S.; Irfan, M.; Reddy, G.S.; Akter, F.; Jahan, D.; Haque, M. Diabetes Mellitus: A Path to Amnesia, Personality, and Behavior Change. Biology 2022, 11, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, A.; Burns, S.; Reddy, A.P.; Culberson, J.; Reddy, P.H. The Role of Obesity and Diabetes in Dementia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhury, A.; Duvoor, C.; Reddy Dendi, V.S.; Kraleti, S.; Chada, A.; Ravilla, R.; Marco, A.; Shekhawat, N.S.; Montales, M.T.; Kuriakose, K.; et al. Clinical Review of Antidiabetic Drugs: Implications for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Management. Front. Endocrinol. 2017, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- LeRoith, D.; Biessels, G.J.; Braithwaite, S.S.; Casanueva, F.F.; Draznin, B.; Halter, J.B.; Hirsch, I.B.; McDonnell, M.E.; Molitch, M.E.; Murad, M.H.; et al. Treatment of Diabetes in Older Adults: An Endocrine Society* Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 104, 1520–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sa-nguanmoo, P.; Tanajak, P.; Kerdphoo, S.; Jaiwongkam, T.; Pratchayasakul, W.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C. SGLT2-Inhibitor and DPP-4 Inhibitor Improve Brain Function via Attenuating Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Insulin Resistance, Inflammation, and Apoptosis in HFD-Induced Obese Rats. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2017, 333, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searcy, J.L.; Phelps, J.T.; Pancani, T.; Kadish, I.; Popovic, J.; Anderson, K.L.; Beckett, T.L.; Murphy, M.P.; Chen, K.-C.; Blalock, E.M.; et al. Long-Term Pioglitazone Treatment Improves Learning and Attenuates Pathological Markers in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2012, 30, 943–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dybjer, E.; Engström, G.; Helmer, C.; Nägga, K.; Rorsman, P.; Nilsson, P.M. Incretin hormones, insulin, glucagon and advanced glycation end products in relation to cognitive function in older people with and without diabetes, a population-based study. Diabet. Med. 2020, 37, 1157–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risner, M.E.; Saunders, A.M.; Altman, J.F.B.; Ormandy, G.C.; Craft, S.; Foley, I.M.; Zvartau-Hind, M.E.; Hosford, D.A.; Roses, A.D.; for the Rosiglitazone in Alzheimer’s Disease Study Group. Efficacy of Rosiglitazone in a Genetically Defined Population with Mild-to-Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease. Pharm. J. 2006, 6, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Strum, J.C.; Shehee, R.; Virley, D.; Richardson, J.; Mattie, M.; Selley, P.; Ghosh, S.; Nock, C.; Saunders, A.; Roses, A. Rosiglitazone Induces Mitochondrial Biogenesis in Mouse Brain. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2007, 11, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, M.; Alderton, C.; Zvartau-Hind, M.; Egginton, S.; Saunders, A.M.; Irizarry, M.; Craft, S.; Landreth, G.; Linnamägi, Ü.; Sawchak, S. Rosiglitazone Monotherapy in Mild-to-Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease: Results from a Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Phase III Study. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2010, 30, 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hsu, C.-C.; Wahlqvist, M.L.; Lee, M.-S.; Tsai, H.-N. Incidence of Dementia Is Increased in Type 2 Diabetes and Reduced by the Use of Sulfonylureas and Metformin. J. Alzheimer’s Dis 2011, 24, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanjan, M.J.; Mohammed, M.; Prashantha Kumar, B.R.; Chandrasekar, M.J.N. Thiazolidinediones as Antidiabetic Agents: A Critical Review. Bioorganic Chem. 2018, 77, 548–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, D.; Yang, S.; Zhao, X.; Wang, G. The Role of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists (GLP-1 RA) in Diabetes-Related Neurodegenerative Diseases. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2022, 16, 665–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, M.; Xie, Y.; Ke, S.; Liu, L.; Pan, X.; Chen, Z. Exenatide Alleviates Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Cognitive Impairment in the 5×FAD Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Behav. Brain Res. 2019, 370, 111932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, A.I.; Candeias, E.; Alves, I.N.; Mena, D.; Silva, D.F.; Machado, N.J.; Campos, E.J.; Santos, M.S.; Oliveira, C.R.; Moreira, P.I. Liraglutide Protects Against Brain Amyloid-Β1–42 Accumulation in Female Mice with Early Alzheimer’s Disease-Like Pathology by Partially Rescuing Oxidative/Nitrosative Stress and Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Porter, W.D.; Flatt, P.R.; Hölscher, C.; Gault, V.A. Liraglutide Improves Hippocampal Synaptic Plasticity Associated with Increased Expression of Mash1 in Ob/Ob Mice. Int. J. Obes. 2013, 37, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cai, H.-Y.; Yang, J.-T.; Wang, Z.-J.; Zhang, J.; Yang, W.; Wu, M.-N.; Qi, J.-S. Lixisenatide Reduces Amyloid Plaques, Neurofibrillary Tangles and Neuroinflammation in an APP/PS1/Tau Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 495, 1034–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölscher, C. Brain Insulin Resistance: Role in Neurodegenerative Disease and Potential for Targeting. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2020, 29, 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Liu, W.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Qi, H.; Liu, S.; Yan, N.; Xing, Y.; Hölscher, C.; Wang, Z. The Novel GLP-1/GIP Analogue DA5-CH Reduces Tau Phosphorylation and Normalizes Theta Rhythm in the Icv. STZ Rat Model of AD. Brain Behav. 2020, 10, e01505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Makrilakis, K. The Role of DPP-4 Inhibitors in the Treatment Algorithm of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: When to Select, What to Expect. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kosaraju, J.; Holsinger, R.M.D.; Guo, L.; Tam, K.Y. Linagliptin, a Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitor, Mitigates Cognitive Deficits and Pathology in the 3xTg-AD Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 6074–6084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Chong, T.; Rodriguez, R.; Pugazhenthi, S. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1-Mediated Modulation of Inflammatory Pathways in the Diabetic Brain: Relevance to Alzheimer’s Disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2016, 13, 1346–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, M.R.; Barbieri, M.; Boccardi, V.; Angellotti, E.; Marfella, R.; Paolisso, G. Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4 Inhibitors Have Protective Effect on Cognitive Impairment in Aged Diabetic Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2014, 69, 1122–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pipatpiboon, N.; Pintana, H.; Pratchayasakul, W.; Chattipakorn, N.; Chattipakorn, S.C. DPP4-Inhibitor Improves Neuronal Insulin Receptor Function, Brain Mitochondrial Function and Cognitive Function in Rats with Insulin Resistance Induced by High-Fat Diet Consumption. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2013, 37, 839–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Teng, S.-W.; Wang, Y.; Qin, F.; Li, Y.; Ai, L.-L.; Yu, H. Sitagliptin Protects the Cognition Function of the Alzheimer’s Disease Mice through Activating Glucagon-like Peptide-1 and BDNF-TrkB Signalings. Neurosci. Lett. 2019, 696, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| S.N. | Disease | Type of Study | Disease Model | Concerned Area of the Brain | Factor Involvement | Outcome of the Study | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Type-2DM | Clinical study Prospective population-based cohort study | T2DM patients | Cerebrum | Risk of dementia (hazard ratio-HR, 1.3 to 2.8), ↑ (Increased) risk of Alzheimer’s disease (HR 1.2 to 3.1). | Increased risk of dementia | [19] |

| 2. | T2DM | Clinical study Longitudinal cohort study | 16,667 patients, Mean age: 65 years Morbidity: T2DM, without prior diagnoses of dementia | Cerebrum | VCI (Vascular cognitive impairment) Incident VCI (RR-Relative risk): 1.62; 95% CI-Confidence interval: 1.12–2.33) | Increase extracellular plaques deposition | [20] |

| 3 | Abnormal insulin Level in AD | Clinical study | Patients with, abnormal insulin Level in Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) and healthy adults | Blood plasma, Cerebrospinal fluid | ↓ (Decrease) CSF (cerebrospinal fluid) insulin concentration led to more advanced dementia. ↑ Plasma insulin levels signified more advanced dementia. | Increased risk for the development of AD | [21] |

| 4. | Type-2DM | Longitudinal study | 2322 adult male participants, Mean age: 50 years old | Hippocampus, cerebellum | ↑risk of dementia, and VD with severe systolic hypertension or heart disease. | Increased risk of AD dementia | [22] |

| 5 | Type-2DM | Epidemiological study | Cohort study 1892 Jewish male civil servant, Mean age: 82 years | Cerebrum | ↑dementia risk factor;(HR = 2.83, 95% CI = 1.40 to 5.71). | Increase the pathogenesis of dementia | [23] |

| 6 | Type-2DM | Population-based Longitudinal cohort study | 2322 adult male participants, Mean age: 50 years old | Hippocampus is the affected part. | Increased risk of AD dementia (HR = 1.31; 95% CI, 1.10–1.56), VD (HR = 1.45; 95% CI, 1.05–2.00). | Increase the risk of cognitive impairment. | [24] |

| 7 | Type-2DM | Clinical study Retrospective longitudinal cohort study | Adult diabetic patients with prior hypoglycaemia had a significantly higher rate of dementia. | Cerebral cortex | One episode (HR = 1.26; 95% CI = 1.03–1.54) | Increased risk of hypoglycaemia | [25] |

| 8 | Type-2DM | Clinical study Retrospective longitudinal cohort study | Age >65 years, diagnosed with T2DM, with no prior diagnosis of dementia | Cerebral cortex | One episode (HR = 1.26; 95% CI = 1.03–1.54) was associated with an increased risk. | Hypoglycaemia is associated with a higher risk of dementia. | [26] |

| 9 | Type-2DM | longitudinal studies | 6184 subjects with diabetes and 38,530 subjects without diabetes | Cerebral cortex and hippocampus | Increased risk of any dementia (RR: 1.51, 95% CI: 1.31–1.74) and increase risk of MCI (RR: 1.21, 95% CI: 1.02–1.45). | Diabetes is a risk factor for incident dementia (including AD, VD, and any dementia). | [27] |

| 10 | Type-2DM | Prospective study | 1066 men and women with T2DM Age: 60–75 years | Cerebral and hippocampus | Severe hypoglycaemia is associated with impaired initial cognitive ability and cognitive decline. | Diabetes is a risk factor for incident dementia | [28] |

| 11 | Type-2DM | Retrospective national record linkage cohort study | 343,062 people with T1DM; 1,855,141 people with T2DM | Cerebral and hippocampus | Risk for developing dementia in T1DM people (RR = 1.65; 95% CI 1.61, 1.68). | Risk of developing dementia in the hippocampus. | [29] |

| 12 | Type-2DM | Long-term prospective cohort study | 135 autopsies of residents of Hisayama town (74 men and 61 women) | Cerebral and hippocampus | The risk of neurotic plaque formation | Increased risk of AD pathology. | [30] |

| Type of Class | Antidiabetic Agent | Types of Patients | Mechanism of Action | Major Role | Risk | Contraindications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potent inhibitor of the sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) | Canagliflozin | Patients with T 2 DM without renal failure | Polyuria and glycosuria are caused by glucose reabsorption in the glomerulus tubule of the kidney and reversible inhibition of SGLT-2 in the proximal tubule of the kidney. | Inhibition of SGLT-2 in the kidney | Glucosuria Ketoacidosis and excessive urination Weight loss | Chronic kidney disease |

| Dapagliflozin | Used in patients to improve glycaemic control with T2DM | |||||

| Empagliflozin | Used to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death in patients with T2DM | |||||

| Sulfonylureas | First generation Chlorpropamide | promote insulin release with T2DM | Prevent calcium influx, insulin secretion, transmembrane depolarization, and ATP-sensitive potassium channels in pancreatic cells. | Increase insulin secretion from pancreatic β cells | hypoglycemia Disulfiram-like reaction agranulocytosis, hemolysis | Cardiovascular comorbidity Obesity Severe renal or liver failure |

| First generation Tolbutamide | promote insulin release with T2DM | |||||

| Second generation Glyburide | Used in elderly patients with diabetes | |||||

| Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP-4) inhibitors | Saxagliptin | Patients with Renal Impairment with T2DM | Indirectly increase the effect of endogenous renin-angiotensin by inhibiting the DPP-4 enzyme, which disintegrates GLP-1, insulin secretion, glucagon secretion, and delayed stomach emptying. | Inhibit GLP-1 degradation | Pancreatitis Nasopharyngitis, Headache, dizziness Arthralgia Edema | Liver failure Renal failure |

| Sitagliptin | Used to reduce blood sugar levels in adults with T2DM | |||||

| Linagliptin | Used to reduce blood sugar levels in adults with T2DM | |||||

| Meglitinides | Nateglinide | Increase the secretion of insulin released by the pancreas with T2DM | ATP-sensitive potassium channels are blocked, cell membranes are depolarized, calcium influx occurs, and insulin secretion is increased. | Increase insulin secretion from pancreatic β cells | hypoglycemia Weight gain | Severe liver failure |

| Repaglinide | It is used when Insulin is not synthesized by the body in a patient with T2DM | |||||

| Thiazolidined iones | Pioglitazone | Used to reduce the risk of cardiovascular death in patients with T2DM | Enhancing adipokine transcription, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) activation can decrease IR. increased insulin secretion. | Reduce IR | Edema Cardiac failure Weight gain Osteoporosis | Congestive heart failure Liver failure |

| Rosiglitazone | Increase the secretion of insulin released by the pancreas with T2DM | |||||

| Amylin analogs | Pramlintide | used to reduce blood sugar levels in adults with T2DM | The secretion of insulin is stimulated by decreased glucagon release, a slower pace of stomach emptying, and an elevated level of satisfaction. | Decrease glucagon release | hypoglycemia Nausea | Gastroparesis |

| Metformin | Biguanides | preventing the production of glucose in the liver and improving insulin sensitivity in T2DM patients | Metformin increases AMPK activity, lowers cAMP, reduces the production of gluconeogenic enzymes, improves insulin sensitivity (via effects on fat metabolism), | Enhances the effect of insulin | Lactic acidosis Weight loss Gastrointestinal Diarrhoea, | Before the administration of iodinated contrast medium and major surgery, metformin must be stopped. |

| Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists (incretin mimetic drugs | Exenatide | used to reduce blood sugar levels in adults with T2DM | Increased food intake stimulates the digestive tract’s endocrine cells to generate GLP-1, which the enzyme DPP-4 breaks down to boost insulin secretion. | Stimulate the GLP-1 receptor | pancreatitis cancer Nausea | Gastrointestinal motility disorders |

| Liraglutide | used to reduce T2DM by improving insulin sensitivity | |||||

| Albiglutide | used to reduce blood sugar levels in adults with T2DM |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Singh, D.D.; Shati, A.A.; Alfaifi, M.Y.; Elbehairi, S.E.I.; Han, I.; Choi, E.-H.; Yadav, D.K. Development of Dementia in Type 2 Diabetes Patients: Mechanisms of Insulin Resistance and Antidiabetic Drug Development. Cells 2022, 11, 3767. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11233767

Singh DD, Shati AA, Alfaifi MY, Elbehairi SEI, Han I, Choi E-H, Yadav DK. Development of Dementia in Type 2 Diabetes Patients: Mechanisms of Insulin Resistance and Antidiabetic Drug Development. Cells. 2022; 11(23):3767. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11233767

Chicago/Turabian StyleSingh, Desh Deepak, Ali A. Shati, Mohammad Y. Alfaifi, Serag Eldin I. Elbehairi, Ihn Han, Eun-Ha Choi, and Dharmendra K. Yadav. 2022. "Development of Dementia in Type 2 Diabetes Patients: Mechanisms of Insulin Resistance and Antidiabetic Drug Development" Cells 11, no. 23: 3767. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11233767

APA StyleSingh, D. D., Shati, A. A., Alfaifi, M. Y., Elbehairi, S. E. I., Han, I., Choi, E. -H., & Yadav, D. K. (2022). Development of Dementia in Type 2 Diabetes Patients: Mechanisms of Insulin Resistance and Antidiabetic Drug Development. Cells, 11(23), 3767. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11233767