Implications of Hypothalamic Neural Stem Cells on Aging and Obesity-Associated Cardiovascular Diseases

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. HtNSCs and Obesity

3. HtNSCs and Inflammation

4. Nrf2, an Important Transcription Factor Affecting NSC Populations in Obesity

5. HtNSCs and Aging

6. Molecular Pathways Associated with NSC Inflammation and Aging

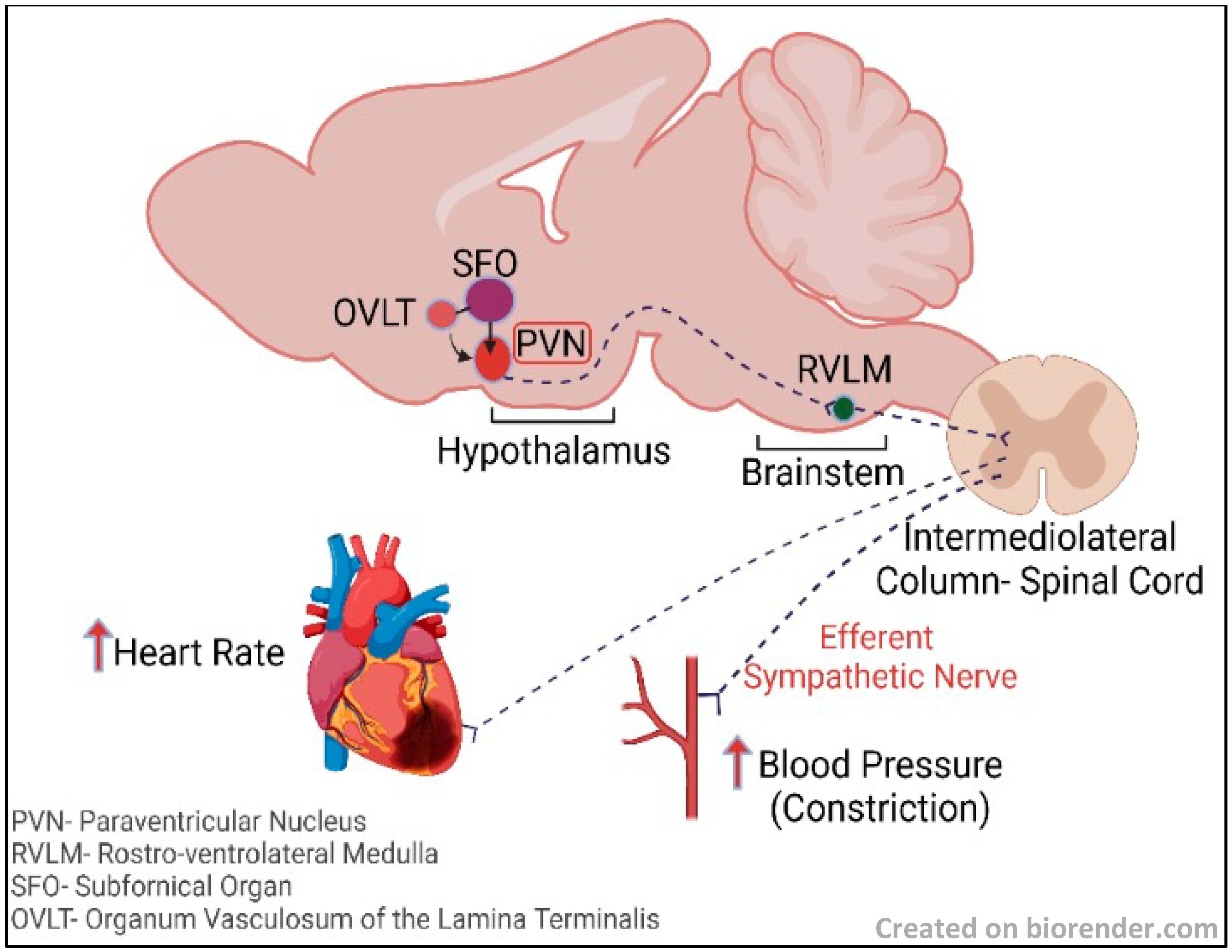

7. The Hypothalamus and the Sympathoexcitatory Effect

8. Time-Restricted Feeding and Its Effect on NSCs

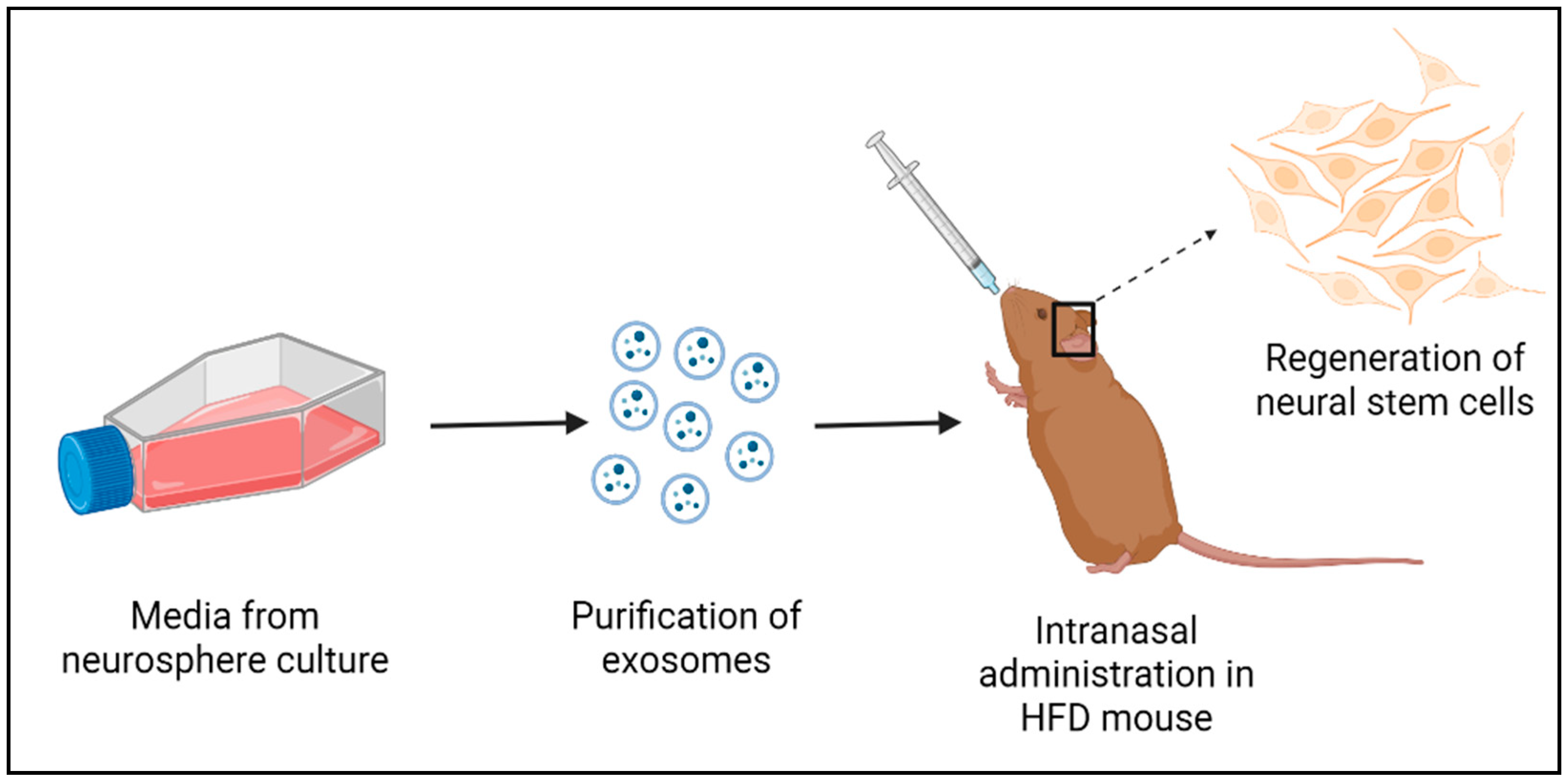

9. Exosomes from the HtNSCs

10. Challenges Associated with NSCs for Regenerative Medicine and Future Perspectives

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bond, A.M.; Ming, G.L.; Song, H. Adult Mammalian Neural Stem Cells and Neurogenesis: Five Decades Later. Cell Stem Cell 2015, 17, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stolp, H.B.; Molnár, Z. Neurogenic niches in the brain: Help and hindrance of the barrier systems. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silva-Vargas, V.; Crouch, E.E.; Doetsch, F. Adult neural stem cells and their niche: A dynamic duo during homeostasis, regeneration, and aging. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2013, 23, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolborea, M.; Dale, N. Hypothalamic tanycytes: Potential roles in the control of feeding and energy balance. Trends Neurosci. 2013, 36, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pellegrino, G.; Trubert, C.; Terrien, J.; Pifferi, F.; Leroy, D.; Loyens, A.; Migaud, M.; Baroncini, M.; Maurage, C.-A.; Fontaine, C.; et al. A comparative study of the neural stem cell niche in the adult hypothalamus of human, mouse, rat and gray mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus). J. Comp. Neurol. 2018, 526, 1419–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xu, Y.; Tamamaki, N.; Noda, T.; Kimura, K.; Itokazu, Y.; Matsumoto, N.; Dezawa, M.; Ide, C. Neurogenesis in the ependymal layer of the adult rat 3rd ventricle. Exp. Neurol. 2005, 192, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.A.; Bedont, J.L.; Pak, T.; Wang, H.; Song, J.; Miranda-Angulo, A.; Takiar, V.; Charubhumi, V.; Balordi, F.; Takebayashi, H.; et al. Tanycytes of the hypothalamic median eminence form a diet-responsive neurogenic niche. Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 700–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, J.; Tang, Y.; Cai, D. IKKβ/NF-κB disrupts adult hypothalamic neural stem cells to mediate a neurodegenerative mechanism of dietary obesity and pre-diabetes. Nat. Cell Biol. 2012, 14, 999–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campisi, J. Cancer, aging and cellular senescence. In Vivo 2000, 14, 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian, P.; Branen, L.; Sivasubramanian, M.K.; Monteiro, R.; Subramanian, M. Aging is associated with glial senescence in the brainstem-implications for age-related sympathetic overactivity. Aging 2021, 13, 13460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nada, M.B.; Slomianka, L.; Vyssotski, A.L.; Lipp, H.P. Early age-related changes in adult hippocampal neurogenesis in C57 mice. Neurobiol. Aging 2010, 31, 151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Chinta, S.J.; Woods, G.; Rane, A.; DeMaria, M.; Campisi, J.; Andersen, J.K. Cellular senescence and the aging brain. Exp. Gerontol. 2015, 68, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuhn, H.G.; Dickinson-Anson, H.; Gage, F.H. Neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the adult rat: Age-related decrease of neuronal progenitor proliferation. J. Neurosci. 1996, 16, 2027–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maslov, A.Y.; Barone, T.A.; Plunkett, R.J.; Pruitt, S.C. Neural stem cell detection, characterization, and age-related changes in the subventricular zone of mice. J. Neurosci. 2004, 24, 1726–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hamilton, L.K.; Dufresne, M.; Joppé, S.E.; Petryszyn, S.; Aumont, A.; Calon, F.; Barnabé-Heider, F.; Furtos, A.; Parent, M.; Chaurand, P.; et al. Aberrant lipid metabolism in the forebrain niche suppresses adult neural stem cell proliferation in an animal model of Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Stem Cell 2015, 17, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ogrodnik, M.; Zhu, Y.I.; Langhi, L.G.; Tchkonia, T.; Krüger, P.; Fielder, E.; Victorelli, S.; Ruswhandi, R.A.; Giorgadze, N.; Pirtskhalava, T.; et al. Obesity-induced cellular senescence drives anxiety and impairs neurogenesis. Cell Metab. 2019, 29, 1061–1077.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Clarke, D.L.; Johansson, C.B.; Wilbertz, J.; Veress, B.; Nilsson, E.; Karlström, H.; Lendahl, U.; Frisén, J. Generalized potential of adult neural stem cells. Science 2000, 288, 1660–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Das, S.; Basu, A. Inflammation: A new candidate in modulating adult neurogenesis. J. Neurosci. Res. 2008, 86, 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucin, K.M.; Wyss-Coray, T. Immune activation in brain aging and neurodegeneration: Too much or too little? Neuron 2009, 64, 110–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Block, M.L.; Hong, J.-S. Microglia and inflammation-mediated neurodegeneration: Multiple triggers with a common mechanism. Prog. Neurobiol. 2005, 76, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNay, D.; Briançon, N.; Kokoeva, M.V.; Maratos-Flier, E.; Flier, J.S. Remodeling of the arcuate nucleus energy-balance circuit is inhibited in obese mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dietrich, M.O.; Horvath, T.L. Fat incites tanycytes to neurogenesis. Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 651–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, N.; Sévigny, J.; Mishra, S.K.; Robson, S.C.; Barth, S.W.; Gerstberger, R.; Hammer, K.; Zimmermann, H. Expression of the ecto-ATPase NTPDase2 in the germinal zones of the developing and adult rat brain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2003, 17, 1355–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frayling, C.; Britton, R.; Dale, N. ATP-mediated glucosensing by hypothalamic tanycytes. J. Physiol. 2011, 589, 2275–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saaltink, D.-J.; Håvik, B.; Verissimo, C.S.; Lucassen, P.; Vreugdenhil, E. Doublecortin and doublecortin-like are expressed in overlapping and non-overlapping neuronal cell population: Implications for neurogenesis. J. Comp. Neurol. 2012, 520, 2805–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroncini, M.; Allet, C.; Leroy, D.; Beauvillain, J.-C.; Francke, J.-P.; Prevot, V. Morphological evidence for direct interaction between gonadotrophin-releasing hormone neurones and astroglial cells in the human hypothalamus. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2007, 19, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Barrett, P.; Ivanova, E.; Graham, E.S.; Ross, A.W.; Wilson, D.; Plé, H.; Mercer, J.G.; Ebling, F.J.; Schuhler, S.; DuPré, S.M.; et al. Photoperiodic regulation of cellular retinoic acid-binding protein 1, GPR50 and nestin in tanycytes of the third ventricle ependymal layer of the Siberian hamster. J. Endocrinol. 2006, 191, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wei, L.-C.; Shi, M.; Chen, L.-W.; Cao, R.; Zhang, P.; Chan, Y. Nestin-containing cells express glial fibrillary acidic protein in the proliferative regions of central nervous system of postnatal developing and adult mice. Dev. Brain Res. 2002, 139, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolborea, M.; Laran-Chich, M.-P.; Rasri, K.; Hildebrandt, H.; Govitrapong, P.; Simonneaux, V.; Pévet, P.; Steinlechner, S.; Klosen, P. Melatonin controls photoperiodic changes in tanycyte vimentin and neural cell adhesion molecule expression in the Djungarian hamster (Phodopus sungorus). Endocrinology 2011, 152, 3871–3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauvet, N.; Prieto, M.; Alonso, G. Tanycytes present in the adult rat mediobasal hypothalamus support the regeneration of monoaminergic axons. Exp. Neurol. 1998, 151, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidibe, A.; Mullier, A.; Chen, P.; Baroncini, M.; Boutin, J.A.; Delagrange, P.; Prevot, V.; Jockers, R. Expression of the orphan GPR50 protein in rodent and human dorsomedial hypothalamus, tanycytes and median eminence. J. Pineal Res. 2010, 48, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarez-Buylla, A.; Cebrian-Silla, A.; Sorrells, S.F.; Nascimento, M.A.; Paredes, M.F.; Garcia-Verdugo, J.M.; Yang, Z.; Huang, E.J. Comment on “Impact of neurodegenerative diseases on human adult hippocampal neurogenesis”. Science 2022, 376, eabn8861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terreros-Roncal, J.; Moreno-Jiménez, E.P.; Flor-García, M.; Rodríguez-Moreno, C.B.; Trinchero, M.F.; Cafini, F.; Rábano, A.; Llorens-Martín, M.; Rose, M.C.; Styr, B.; et al. Impact of neurodegenerative diseases on human adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Science 2021, 374, 1106–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorrells, S.F.; Paredes, M.F.; Velmeshev, D.; Herranz-Pérez, V.; Sandoval, K.; Mayer, S.; Chang, E.F.; Insausti, R.; Kriegstein, A.R.; Rubenstein, J.L.; et al. Immature excitatory neurons develop during adolescence in the human amygdala. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dietrich, M.O.; Horvath, T.L. Synaptic plasticity of feeding circuits: Hormones and hysteresis. Cell 2011, 146, 863–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dietrich, M.O.; Horvath, T.L. Hypothalamic control of energy balance: Insights into the role of synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2013, 36, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flier, J.S. Regulating energy balance: The substrate strikes back. Science 2006, 312, 861–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niswender, K.D.; Baskin, D.; Schwartz, M. Insulin and its evolving partnership with leptin in the hypothalamic control of energy homeostasis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 15, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coll, A.P.; Farooqi, I.S.; O’Rahilly, S. The hormonal control of food intake. Cell 2007, 129, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Münzberg, H.; Myers, M.G. Molecular and anatomical determinants of central leptin resistance. Nat. Neurosci. 2005, 8, 566–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, L.E.; Unger, E.K.; Cheung, C.C.; Xu, A.W. Modulation of AgRP-neuronal function by SOCS3 as an initiating event in diet-induced hypothalamic leptin resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E697–E706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thaler, J.P.; Yi, C.-X.; Schur, E.A.; Guyenet, S.J.; Hwang, B.H.; Dietrich, M.O.; Zhao, X.; Sarruf, D.A.; Izgur, V.; Maravilla, K.R.; et al. Obesity is associated with hypothalamic injury in rodents and humans. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Padilla, S.L.; Carmody, J.S.; Zeltser, L.M. Pomc-expressing progenitors give rise to antagonistic neuronal populations in hypothalamic feeding circuits. Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 403–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kokoeva, M.V.; Yin, H.; Flier, J.S. Evidence for constitutive neural cell proliferation in the adult murine hypothalamus. J. Comp. Neurol. 2007, 505, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, A.A.; Xu, A.W. De novo neurogenesis in adult hypothalamus as a compensatory mechanism to regulate energy balance. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fonseca, R.S.; Mahesula, S.; Apple, D.M.; Raghunathan, R.; Dugan, A.; Cardona, A.; O’Connor, J.; Kokovay, E. Neurogenic niche microglia undergo positional remodeling and progressive activation contributing to age-associated reductions in neurogenesis. Stem Cells Dev. 2016, 25, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokaia, Z.; Martino, G.; Schwartz, M.; Lindvall, O. Cross-talk between neural stem cells and immune cells: The key to better brain repair? Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 1078–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breton, J.; Mao-Draayer, Y. Impact of cytokines on neural stem/progenitor cell fate. J. Neurol. Neurophysiol. 2011, S4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kandasamy, M.; Lehner, B.; Kraus, S.; Sander, P.R.; Marschallinger, J.; Rivera, F.J.; Trümbach, D.; Ueberham, U.; Reitsamer, H.A.; Strauss, O.; et al. TGF-beta signalling in the adult neurogenic niche promotes stem cell quiescence as well as generation of new neurons. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2014, 18, 1444–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wachs, F.-P.; Winner, B.; Couillard-Despres, S.; Schiller, T.; Aigner, R.; Winkler, J.; Bogdahn, U.; Aigner, L. Transforming growth factor-β1 is a negative modulator of adult neurogenesis. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2006, 65, 358–370. [Google Scholar]

- Katsimpardi, L.; Litterman, N.K.; Schein, P.A.; Miller, C.M.; Loffredo, F.S.; Wojtkiewicz, G.R.; Chen, J.W.; Lee, R.T.; Wagers, A.J.; Rubin, L.L. Vascular and neurogenic rejuvenation of the aging mouse brain by young systemic factors. Science 2014, 344, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bouchard, J.; Villeda, S.A. Aging and brain rejuvenation as systemic events. J. Neurochem. 2015, 132, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, H.; Karin, M.; Bai, H.; Cai, D. Hypothalamic IKKβ/NF-κB and ER stress link overnutrition to energy imbalance and obesity. Cell 2008, 135, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kievit, P.; Howard, J.K.; Badman, M.K.; Balthasar, N.; Coppari, R.; Mori, H.; Lee, C.E.; Elmquist, J.K.; Yoshimura, A.; Flier, J.S. Enhanced leptin sensitivity and improved glucose homeostasis in mice lacking suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 in POMC-expressing cells. Cell Metab. 2006, 4, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mori, H.; Hanada, R.; Hanada, T.; Aki, D.; Mashima, R.; Nishinakamura, H.; Torisu, T.; Chien, K.R.; Yasukawa, H.; Yoshimura, A. Socs3 deficiency in the brain elevates leptin sensitivity and confers resistance to diet-induced obesity. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 739–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, A.S.; Unger, E.K.; Olofsson, L.E.; Piper, M.L., Jr.; Myers, M.G.; Xu, A.W. Functional role of suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 upregulation in hypothalamic leptin resistance and long-term energy homeostasis. Diabetes 2010, 59, 894–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zabolotny, J.M.; Kim, Y.-B.; Welsh, L.A.; Kershaw, E.E.; Neel, B.G.; Kahn, B.B. Protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B expression is induced by inflammation in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 14230–14241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banno, R.; Zimmer, D.; De Jonghe, B.C.; Atienza, M.; Rak, K.; Yang, W.; Bence, K.K. PTP1B and SHP2 in POMC neurons reciprocally regulate energy balance in mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 720–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bence, K.; Delibegovic, M.; Xue, B.; Gorgun, C.Z.; Hotamisligil, G.S.; Neel, B.G.; Kahn, B.B. Neuronal PTP1B regulates body weight, adiposity and leptin action. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picardi, P.K.; Calegari, V.C.; Prada, P.D.O.; Moraes, J.C.; Araújo, E.; Marcondes, M.C.C.G.; Ueno, M.; Carvalheira, J.B.C.; Velloso, L.A.; Saad, M.J.A. Reduction of hypothalamic protein tyrosine phosphatase improves insulin and leptin resistance in diet-induced obese rats. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 3870–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, G.; Cheung, S.; Galeano, J.; Ji, A.X.; Qin, Q.; Bi, X. Allopregnanolone treatment delays cholesterol accumulation and reduces autophagic/lysosomal dysfunction and inflammation in Npc1−/− mouse brain. Brain Res. 2009, 1270, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dugan, L.L.; Ali, S.S.; Shekhtman, G.; Roberts, A.J.; Lucero, J.; Quick, K.L.; Behrens, M.M. IL-6 mediated degeneration of forebrain GABAergic interneurons and cognitive impairment in aged mice through activation of neuronal NADPH oxidase. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niture, S.K.; Jaiswal, A.K. Nrf2 protein up-regulates antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 and prevents cellular apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 9873–9886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Paek, J.; Lo, J.Y.; Narasimhan, S.D.; Nguyen, T.N.; Glover-Cutter, K.; Robida-Stubbs, S.; Suzuki, T.; Yamamoto, M.; Blackwell, T.K.; Curran, S.P. Mitochondrial SKN-1/Nrf mediates a conserved starvation response. Cell Metab. 2012, 16, 526–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Murakami, S.; Motohashi, H. Roles of Nrf2 in cell proliferation and differentiation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 88, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sykiotis, G.P.; Bohmann, D. Keap1/Nrf2 signaling regulates oxidative stress tolerance and lifespan in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 2008, 14, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Balasubramanian, P.; Asirvatham-Jeyaraj, N.; Monteiro, R.; Sivasubramanian, M.K.; Hall, D.; Subramanian, M. Obesity-induced sympathoexcitation is associated with Nrf2 dysfunction in the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Am. J. Physiol.-Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2020, 318, R435–R444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Belle, J.E.; Orozco, N.M.; Paucar, A.A.; Saxe, J.P.; Mottahedeh, J.; Pyle, A.D.; Wu, H.; Kornblum, H.I. Proliferative neural stem cells have high endogenous ROS levels that regulate self-renewal and neurogenesis in a PI3K/Akt-dependant manner. Cell Stem Cell 2011, 8, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dodson, M.; Anandhan, A.; Zhang, D.D.; Madhavan, L. An NRF2 perspective on stem cells and ageing. Front. Aging 2021, 2, 690686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Meng, S.; Li, Y.; Ghebre, Y.T.; Cooke, J.P. Optimal ROS signaling is critical for nuclear reprogramming. Cell Rep. 2016, 15, 919–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ray, S.; Corenblum, M.J.; Anandhan, A.; Reed, A.; Ortiz, F.O.; Zhang, D.D.; Barnes, C.A.; Madhavan, L. A role for Nrf2 expression in defining the aging of hippocampal neural stem cells. Cell Transplant. 2018, 27, 589–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- López-Otín, C.; Blasco, M.A.; Partridge, L.; Serrano, M.; Kroemer, G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 2013, 153, 1194–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nunan, E.; Wright, C.L.; Semola, O.A.; Subramanian, M.; Balasubramanian, P.; Lovern, P.C.; Fancher, I.S.; Butcher, J.T. Obesity as a premature aging phenotype—Implications for sarcopenic obesity. GeroScience 2022, 44, 1393–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dacks, P.A.; Moreno, C.L.; Kim, E.S.; Marcellino, B.K.; Mobbs, C.V. Role of the hypothalamus in mediating protective effects of dietary restriction during aging. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2013, 34, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sadagurski, M.; Landeryou, T.; Cady, G.; Bartke, A.; Bernal-Mizrachi, E.; Miller, R.A. Transient early food restriction leads to hypothalamic changes in the long-lived crowded litter female mice. Physiol. Rep. 2015, 3, e12379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, A.; Brace, C.S.; Rensing, N.; Cliften, P.; Wozniak, D.F.; Herzog, E.D.; Yamada, K.A.; Imai, S.-I. Sirt1 extends life span and delays aging in mice through the regulation of Nk2 homeobox 1 in the DMH and LH. Cell Metab. 2013, 18, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, G.; Li, J.; Purkayastha, S.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yin, Y.; Li, B.; Liu, G.; Cai, D. Hypothalamic programming of systemic ageing involving IKK-β, NF-κB and GnRH. Nature 2013, 497, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cai, D. Neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in overnutrition-induced diseases. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 24, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Posey, K.A.; Clegg, D.J.; Printz, R.L.; Byun, J.; Morton, G.J.; Vivekanandan-Giri, A.; Pennathur, S.; Baskin, D.G.; Heinecke, J.W.; Woods, S.C.; et al. Hypothalamic proinflammatory lipid accumulation, inflammation, and insulin resistance in rats fed a high-fat diet. Am. J. Physiol. -Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 296, E1003–E1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolp, H.B.; Turnquist, C.; Dziegielewska, K.M.; Saunders, N.; Anthony, D.; Molnar, Z. Reduced ventricular proliferation in the foetal cortex following maternal inflammation in the mouse. Brain 2011, 134, 3236–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Y.; Kim, M.S.; Jia, B.; Yan, J.; Zuniga-Hertz, J.P.; Han, C.; Cai, D. Hypothalamic stem cells control ageing speed partly through exosomal miRNAs. Nature 2017, 548, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molofsky, A.V.; Pardal, R.; Iwashita, T.; Park, I.-K.; Clarke, M.F.; Morrison, S.J. Bmi-1 dependence distinguishes neural stem cell self-renewal from progenitor proliferation. Nature 2003, 425, 962–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stoll, E.A.; Cheung, W.; Mikheev, A.M.; Sweet, I.R.; Bielas, J.H.; Zhang, J.; Rostomily, R.C.; Horner, P.J. Aging neural progenitor cells have decreased mitochondrial content and lower oxidative metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 38592–38601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Finkel, T.; Deng, C.X.; Mostoslavsky, R. Recent progress in the biology and physiology of sirtuins. Nature 2009, 460, 587–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hagenbuchner, J.; Ausserlechner, M.J. Mitochondria and FOXO3: Breath or die. Front. Physiol. 2013, 4, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sakata, H.; Narasimhan, P.; Niizuma, K.; Maier, C.M.; Wakai, T.; Chan, P.H. Interleukin 6-preconditioned neural stem cells reduce ischaemic injury in stroke mice. Brain 2012, 135, 3298–3310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paik, J.-H.; Ding, Z.; Narurkar, R.; Ramkissoon, S.; Muller, F.; Kamoun, W.S.; Chae, S.-S.; Zheng, H.; Ying, H.; Mahoney, J.; et al. FoxOs cooperatively regulate diverse pathways governing neural stem cell homeostasis. Cell Stem Cell 2009, 5, 540–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gemma, C.; Vila, J.; Bachstetter, A.; Bickford, P.C. Oxidative stress and the aging brain: From theory to prevention. Brain Aging 2007, 353–374. [Google Scholar]

- Lionaki, E.; Markaki, M.; Palikaras, K.; Tavernarakis, N. Mitochondria, autophagy and age-associated neurodegenerative diseases: New insights into a complex interplay. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Bioenerg. 2015, 1847, 1412–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moore, D.L.; Pilz, G.A.; Araúzo-Bravo, M.J.; Barral, Y.; Jessberger, S. A mechanism for the segregation of age in mammalian neural stem cells. Science 2015, 349, 1334–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumdar, J.; O’Brien, W.T.; Johnson, R.; LaManna, J.; Chavez, J.C.; Klein, P.S.; Simon, M.C. O2 regulates stem cells through Wnt/β-catenin signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 2010, 12, 1007–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabie, T.; Kunze, R.; Marti, H.H. Impaired hypoxic response in senescent mouse brain. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2011, 29, 655–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aberg, M.A.; Åberg, N.D.; Hedbäcker, H.; Oscarsson, J.; Eriksson, P.S. Peripheral infusion of IGF-I selectively induces neurogenesis in the adult rat hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 2896–2903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sonntag, W.E.; Ramsey, M.; Carter, C.S. Growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and their influence on cognitive aging. Ageing Res. Rev. 2005, 4, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaker, Z.; Aïd, S.; Berry, H.; Holzenberger, M. Suppression of IGF-I signals in neural stem cells enhances neurogenesis and olfactory function during aging. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cota, D.; Proulx, K.; Blake Smith, K.A.; Kozma, S.C.; Thomas, G.; Woods, S.C.; Seeley, R.J. Hypothalamic mTOR signaling regulates food intake. Science 2006, 312, 927–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- de Morentin, P.M.; Martinez-Sanchez, N.; Roa, J.; Ferno, J.; Nogueiras, R.; Tena-Sempere, M.; Dieguez, C.; Lopez, M. Hypothalamic mTOR: The rookie energy sensor. Curr. Mol. Med. 2014, 14, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.-B.; Tien, A.-C.; Boddupalli, G.; Xu, A.W.; Jan, Y.N.; Jan, L.Y. Rapamycin ameliorates age-dependent obesity associated with increased mTOR signaling in hypothalamic POMC neurons. Neuron 2012, 75, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mori, H.; Inoki, K.; Münzberg, H.; Opland, D.; Faouzi, M.; Villanueva, E.C.; Ikenoue, T.; Kwiatkowski, D.; MacDougald, O.A.; Myers, M.G.; et al. Critical role for hypothalamic mTOR activity in energy balance. Cell Metab. 2009, 9, 362–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, H.; Stevens, C.F.; Gage, F.H. Astroglia induce neurogenesis from adult neural stem cells. Nature 2002, 417, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, M.; Inoue, K.; Iwamura, H.; Terashima, K.; Soya, H.; Asashima, M.; Kuwabara, T. Reduction in paracrine Wnt3 factors during aging causes impaired adult neurogenesis. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 3570–3582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miranda, C.J.; Braun, L.; Jiang, Y.; Hester, M.E.; Zhang, L.; Riolo, M.; Wang, H.; Rao, M.; Altura, R.A.; Kaspar, B.K. Aging brain microenvironment decreases hippocampal neurogenesis through Wnt-mediated survivin signaling. Aging Cell 2012, 11, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Seib, D.R.; Corsini, N.S.; Ellwanger, K.; Plaas, C.; Mateos, A.; Pitzer, C.; Niehrs, C.; Celikel, T.; Martin-Villalba, A. Loss of Dickkopf-1 restores neurogenesis in old age and counteracts cognitive decline. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 12, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gattazzo, F.; Urciuolo, A.; Bonaldo, P. Extracellular matrix: A dynamic microenvironment for stem cell niche. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Gen. Subj. 2014, 1840, 2506–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keung, A.J.; de Juan-Pardo, E.M.; Schaffer, D.V.; Kumar, S. Rho GTPases mediate the mechanosensitive lineage commitment of neural stem cells. Stem Cells 2011, 29, 1886–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zang, L.; Zhang, F.; Chen, J.; Shen, H.; Shu, L.; Liang, F.; Feng, C.; Chen, D.; Tao, H.; et al. Fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) protein regulates adult neurogenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2017, 26, 2398–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haussmann, I.U.; Bodi, Z.; Sanchez-Moran, E.; Mongan, N.P.; Archer, N.; Fray, R.G.; Soller, M. m6A potentiates Sxl alternative pre-mRNA splicing for robust Drosophila sex determination. Nature 2016, 540, 301–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nainar, S.; Marshall, P.R.; Tyler, C.R.; Spitale, R.C.; Bredy, T.W. Evolving insights into RNA modifications and their functional diversity in the brain. Nat. Neurosci. 2016, 19, 1292–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yue, Y.; Liu, J.; He, C. RNA N6-methyladenosine methylation in post-transcriptional gene expression regulation. Genes Dev. 2015, 29, 1343–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bouret, S.G.; Simerly, R.B. Minireview: Leptin and development of hypothalamic feeding circuits. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 2621–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lang, B.T.; Yan, Y.; Dempsey, R.J.; Vemuganti, R. Impaired neurogenesis in adult type-2 diabetic rats. Brain Res. 2009, 1258, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Beauquis, J.; Saravia, F.; Coulaud, J.; Roig, P.; Dardenne, M.; Homo-Delarche, F.; De Nicola, A. Prominently decreased hippocampal neurogenesis in a spontaneous model of type 1 diabetes, the nonobese diabetic mouse. Exp. Neurol. 2008, 210, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, H.; Cai, F.; Belsham, D.D. Leptin signaling in neurotensin neurons involves STAT, MAP kinases ERK1/2, and p38 through c-Fos and ATF1. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 2654–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Desai, M.; Li, T.; Ross, M.G. Fetal hypothalamic neuroprogenitor cell culture: Preferential differentiation paths induced by leptin and insulin. Endocrinology 2011, 152, 3192–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunbar, J.C.; Lu, H. Leptin-induced increase in sympathetic nervous and cardiovascular tone is mediated by proopiomelanocortin (POMC) products. Brain Res. Bull. 1999, 50, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haynes, W.G.; Morgan, N.A.; Djalali, A.; Sivitz, W.I.; Mark, A.L. Interactions between the melanocortin system and leptin in control of sympathetic nerve traffic. Hypertension 1999, 33, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cone, R.D. Anatomy and regulation of the central melanocortin system. Nat. Neurosci. 2005, 8, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, C.; Sarvetnick, N. The incidence of type-1 diabetes in NOD mice is modulated by restricted flora not germ-free conditions. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e17049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Myers, M.G.; Münzberg, H.; Leinninger, G.M.; Leshan, R.L. The geometry of leptin action in the brain: More complicated than a simple ARC. Cell Metab. 2009, 9, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ulrich-Lai, Y.M.; Jones, K.R.; Ziegler, D.R.; Cullinan, W.E.; Herman, J. Forebrain origins of glutamatergic innervation to the rat paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus: Differential inputs to the anterior versus posterior subregions. J. Comp. Neurol. 2011, 519, 1301–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mercer, A.J.; Hentges, S.T.; Meshul, C.K.; Low, M.J. Unraveling the central proopiomelanocortin neural circuits. Front. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kawabe, T.; Kawabe, K.; Sapru, H.N. Cardiovascular responses to chemical stimulation of the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus in the rat: Role of the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e45180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawabe, T.; Kawabe, K.; Sapru, H.N. Effect of barodenervation on cardiovascular responses elicited from the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus of the rat. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e53111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cassaglia, P.A.; Shi, Z.; Li, B.; Reis, W.L.; Clute-Reinig, N.M.; Stern, J.E.; Brooks, V.L. Neuropeptide Y acts in the paraventricular nucleus to suppress sympathetic nerve activity and its baroreflex regulation. J. Physiol. 2014, 592, 1655–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobst, E.E.; Enriori, P.J.; Cowley, M.A. The electrophysiology of feeding circuits. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2004, 15, 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varela, L.; Horvath, T.L. Leptin and insulin pathways in POMC and AgRP neurons that modulate energy balance and glucose homeostasis. EMBO Rep. 2012, 13, 1079–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, J.E.; da Silva, A.A.; do Carmo, J.M.; Dubinion, J.; Hamza, S.; Munusamy, S.; Smith, G.; Stec, D.E. Obesity-induced hypertension: Role of sympathetic nervous system, leptin, and melanocortins. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 17271–17276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kohsaka, A.; Laposky, A.D.; Ramsey, K.M.; Estrada, C.; Joshu, C.; Kobayashi, Y.; Turek, F.W.; Bass, J. High-fat diet disrupts behavioral and molecular circadian rhythms in mice. Cell Metab. 2007, 6, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- La Fleur, S.E.; Van Rozen, A.J.; Luijendijk, M.C.M.; Groeneweg, F.; Adan, R.A.H. A free-choice high-fat high-sugar diet induces changes in arcuate neuropeptide expression that support hyperphagia. Int. J. Obes. 2010, 34, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, S.; Storlien, L.H.; Huang, X.F. Leptin receptor, NPY, POMC mRNA expression in the diet-induced obese mouse brain. Brain Res. 2000, 875, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouret, S.G.; Gorski, J.N.; Patterson, C.M.; Chen, S.; Levin, B.E.; Simerly, R.B. Hypothalamic neural projections are permanently disrupted in diet-induced obese rats. Cell Metab. 2008, 7, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shi, Z.; Li, B.; Brooks, V.L. Role of the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus in the sympathoexcitatory effects of leptin. Hypertension 2015, 66, 1034–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Plakkot, B.; Subramanian, M. Evaluation of Hypothalamic Neural Stem Cell Niche–Implications on Obesity-Induced Sympathoexcitation. FASEB J. 2022, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, M.P.; Arumugam, T.V. Hallmarks of brain aging: Adaptive and pathological modification by metabolic states. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 1176–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mana, M.D.; Kuo, E.Y.S.; Yilmaz, Ö.H. Dietary regulation of adult stem cells. Curr. Stem Cell Rep. 2017, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Arumugam, T.; Phillips, T.M.; Cheng, A.; Morrell, C.H.; Mattson, M.P.; Wan, R. Age and energy intake interact to modify cell stress pathways and stroke outcome. Ann. Neurol. 2010, 67, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Halagappa, V.K.M.; Guo, Z.; Pearson, M.; Matsuoka, Y.; Cutler, R.G.; LaFerla, F.M.; Mattson, M.P. Intermittent fasting and caloric restriction ameliorate age-related behavioral deficits in the triple-transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2007, 26, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzanero, S.; Erion, J.R.; Santro, T.; Steyn, F.J.; Chen, C.; Arumugam, T.V.; Stranahan, A.M. Intermittent fasting attenuates increases in neurogenesis after ischemia and reperfusion and improves recovery. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2014, 34, 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bruce-Keller, A.J.; Umberger, G.; McFall, R.; Mattson, M.P. Food restriction reduces brain damage and improves behavioral outcome following excitotoxic and metabolic insults. Ann. Neurol. Off. J. Am. Neurol. Assoc. Child Neurol. Soc. 1999, 45, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kang, S.-W.; Mallilankaraman, K.; Baik, S.-H.; Lim, J.C.; Balaganapathy, P.; She, D.T.; Lok, K.-Z.; Fann, D.Y.; Thambiayah, U.; et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals intermittent fasting-induced genetic changes in ischemic stroke. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 1497–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, S.; Rajeev, V.; Fann, D.Y.; Jo, D.; Arumugam, T.V. Intermittent fasting increases adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Brain Behav. 2020, 10, e01444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hitoshi, S.; Alexson, T.; Tropepe, V.; Donoviel, D.; Elia, A.J.; Nye, J.S.; Conlon, R.A.; Mak, T.W.; Bernstein, A.; van der Kooy, D. Notch pathway molecules are essential for the maintenance, but not the generation, of mammalian neural stem cells. Genes Dev. 2002, 16, 846–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brai, E.; Marathe, S.; Astori, S.; Ben Fredj, N.; Perry, E.; Lamy, C.; Scotti, A.; Alberi, L. Notch1 regulates hippocampal plasticity through interaction with the reelin pathway, glutamatergic transmission and CREB signaling. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- He, W.; Tian, X.; Yuan, B.; Chu, B.; Gao, F.; Wang, H. Rosuvastatin improves neurite extension in cortical neurons through the Notch 1/BDNF pathway. Neurol. Res. 2019, 41, 658–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schölzke, M.N.; Schwaninger, M. Transcriptional regulation of neurogenesis: Potential mechanisms in cerebral ischemia. J. Mol. Med. 2007, 85, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colman, R.J.; Beasley, T.M.; Kemnitz, J.W.; Johnson, S.C.; Weindruch, R.; Anderson, R.M. Caloric restriction reduces age-related and all-cause mortality in rhesus monkeys. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fontana, L.; Partridge, L.; Longo, V.D. Extending healthy life span—From yeast to humans. Science 2010, 328, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Longo, V.D.; Fontana, L. Calorie restriction and cancer prevention: Metabolic and molecular mechanisms. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2010, 31, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mercken, E.M.; Carboneau, B.A.; Krzysik-Walker, S.M.; de Cabo, R. Of mice and men: The benefits of caloric restriction, exercise, and mimetics. Ageing Res. Rev. 2012, 11, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berryman, D.; Christiansen, J.S.; Johannsson, G.; Thorner, M.O.; Kopchick, J.J. Role of the GH/IGF-1 axis in lifespan and healthspan: Lessons from animal models. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2008, 18, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Longo, V.D.; Mattson, M.P. Fasting: Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications. Cell Metab. 2014, 19, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.; Duan, W.; Long, J.M.; Ingram, D.K.; Mattson, M.P. Dietary restriction increases the number of newly generated neural cells, and induces BDNF expression, in the dentate gyrus of rats. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2000, 15, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Seroogy, K.B.; Mattson, M.P. Dietary restriction enhances neurotrophin expression and neurogenesis in the hippocampus of adult mice. J. Neurochem. 2002, 80, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brandhorst, S.; Choi, I.Y.; Wei, M.; Cheng, C.W.; Sedrakyan, S.; Navarrete, G.; Dubeau, L.; Yap, L.P.; Park, R.; Vinciguerra, M.; et al. A periodic diet that mimics fasting promotes multi-system regeneration, enhanced cognitive performance, and healthspan. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheng, C.W.; Adams, G.B.; Perin, L.; Wei, M.; Zhou, X.; Lam, B.S.; Da Sacco, S.; Mirisola, M.; Quinn, D.I.; Dorff, T.B.; et al. Prolonged fasting reduces IGF-1/PKA to promote hematopoietic-stem-cell-based regeneration and reverse immunosuppression. Cell Stem Cell 2014, 14, 810–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ng, S.Y.; Johnson, R.; Stanton, L.W. Human long non-coding RNAs promote pluripotency and neuronal differentiation by association with chromatin modifiers and transcription factors. EMBO J. 2012, 31, 522–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; He, L.; Du, Y.; Zhu, P.; Huang, G.; Luo, J.; Yan, X.; Ye, B.; Li, C.; Xia, P.; et al. The long noncoding RNA lncTCF7 promotes self-renewal of human liver cancer stem cells through activation of Wnt signaling. Cell Stem Cell 2015, 16, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loewer, S.; Cabili, M.N.; Guttman, M.; Loh, Y.H.; Thomas, K.; Park, I.H.; Garber, M.; Curran, M.; Onder, T.; Agarwal, S.; et al. Large intergenic non-coding RNA-RoR modulates reprogramming of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 1113–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiao, Y.Z.; Yang, M.; Xiao, Y.; Guo, Q.; Huang, Y.; Li, C.J.; Cai, D.; Luo, X.H. Reducing hypothalamic stem cell senescence protects against aging-associated physiological decline. Cell Metab. 2020, 31, 534–548.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, H.-G.; Lindquist, J.A.; Keilhoff, G.; Dobrowolny, H.; Brandt, S.; Steiner, J.; Bogerts, B.; Mertens, P.R. Differential distribution of Y-box-binding protein 1 and cold shock domain protein A in developing and adult human brain. Brain Struct. Funct. 2015, 220, 2235–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- En-Nia, A.; Yilmaz, E.; Klinge, U.; Lovett, D.H.; Stefanidis, I.; Mertens, P.R. Transcription factor YB-1 mediates DNA polymerase α gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 7702–7711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Izumi, H.; Imamura, T.; Nagatani, G.; Ise, T.; Murakami, T.; Uramoto, H.; Torigoe, T.; Ishiguchi, H.; Yoshida, Y.; Nomoto, M.; et al. Y box-binding protein-1 binds preferentially to single-stranded nucleic acids and exhibits 3′→ 5′ exonuclease activity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29, 1200–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kotake, Y.; Ozawa, Y.; Harada, M.; Kitagawa, K.; Niida, H.; Morita, Y.; Tanaka, K.; Suda, T.; Kitagawa, M. YB 1 binds to and represses the p16 tumor suppressor gene. Genes Cells 2013, 18, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anandhan, A.; Tamilselvam, K.; Radhiga, T.; Rao, S.; Essa, M.M.; Manivasagam, T. Theaflavin, a black tea polyphenol, protects nigral dopaminergic neurons against chronic MPTP/probenecid induced Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res. 2012, 1433, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishino, J.; Kim, I.; Chada, K.; Morrison, S.J. Hmga2 promotes neural stem cell self-renewal in young but not old mice by reducing p16Ink4a and p19Arf Expression. Cell 2008, 135, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lowe, S.W.; Sherr, C.J. Tumor suppression by Ink4a–Arf: Progress and puzzles. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2003, 13, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molofsky, A.V.; Slutsky, S.G.; Joseph, N.M.; He, S.; Pardal, R.; Krishnamurthy, J.; Sharpless, N.E.; Morrison, S.J. Increasing p16INK4a expression decreases forebrain progenitors and neurogenesis during ageing. Nature 2006, 443, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhao, C.; Sun, G.; Li, S.; Lang, M.-F.; Yang, S.; Li, W.; Shi, Y. MicroRNA let-7b regulates neural stem cell proliferation and differentiation by targeting nuclear receptor TLX signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 1876–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nishino, J.; Kim, S.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Morrison, S.J. A network of heterochronic genes including Imp1 regulates temporal changes in stem cell properties. Elife 2013, 2, e00924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafranski, K.; Abraham, K.J.; Mekhail, K. Non-coding RNA in neural function, disease, and aging. Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spinelli, M.; Natale, F.; Rinaudo, M.; Leone, L.; Mezzogori, D.; Fusco, S.; Grassi, C. Neural Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Revert HFD-Dependent Memory Impairment via CREB-BDNF Signalling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reekmans, K.; Praet, J.; Daans, J.; Reumers, V.; Pauwels, P.; Van Der Linden, A.; Berneman, Z.N.; Ponsaerts, P. Current challenges for the advancement of neural stem cell biology and transplantation research. Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2012, 8, 262–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellin, M.; Marchetto, M.C.; Gage, F.H.; Mummery, C.L. Induced pluripotent stem cells: The new patient? Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Plakkot, B.; Di Agostino, A.; Subramanian, M. Implications of Hypothalamic Neural Stem Cells on Aging and Obesity-Associated Cardiovascular Diseases. Cells 2023, 12, 769. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12050769

Plakkot B, Di Agostino A, Subramanian M. Implications of Hypothalamic Neural Stem Cells on Aging and Obesity-Associated Cardiovascular Diseases. Cells. 2023; 12(5):769. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12050769

Chicago/Turabian StylePlakkot, Bhuvana, Ashley Di Agostino, and Madhan Subramanian. 2023. "Implications of Hypothalamic Neural Stem Cells on Aging and Obesity-Associated Cardiovascular Diseases" Cells 12, no. 5: 769. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12050769