Possibility of Cell Block Specimens from Overnight-Stored Bile for Next-Generation Sequencing of Cholangiocarcinoma

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

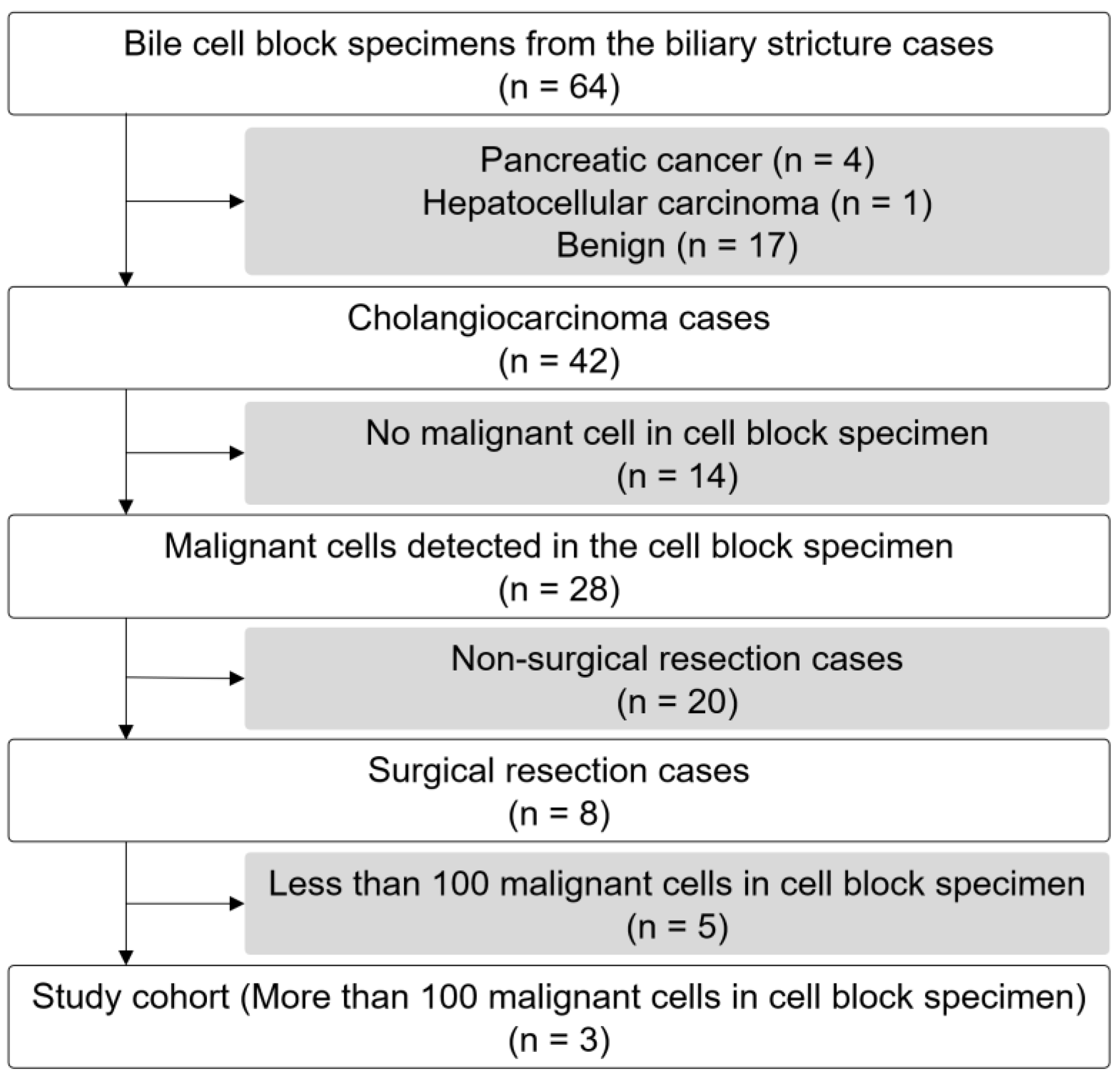

2.1. Study Design, Patient Population, and Specimen Collection

2.2. Next-Generation Sequencing

2.3. Druggable or Cancer-Related Genetic Alterations

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics and Endoscopic Findings

3.2. Quantity and Quality of DNA and RNA Extracted Bile CB and Surgically Resected Specimens

3.3. Total Number of Reads in NGS and NGS Quality

3.4. Short Variant, CNV, Splice Variants, and Fusion

3.5. Genetic Alterations

3.6. Druggable or Cancer-Related Genetic Alterations, MSI, and TMB

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Banales, J.M.; Marin, J.J.G.; Lamarca, A.; Rodrigues, P.M.; Khan, S.A.; Roberts, L.R.; Cardinale, V.; Carpino, G.; Andersen, J.B.; Braconi, C.; et al. Cholangiocarcinoma 2020: The next horizon in mechanisms and management. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 17, 557–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antwi, S.O.; Mousa, O.Y.; Patel, T. Racial, Ethnic, and Age Disparities in Incidence and Survival of Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma in the United States; 1995–2014. Ann. Hepatol. 2018, 17, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, R.J.; Jain, A.K.; Brandwein, S.L.; Wang, H.; Chuttani, R.; Pleskow, D.K. The combination of stricture dilation, endoscopic needle aspiration, and biliary brushings significantly improves diagnostic yield from malignant bile duct strictures. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2001, 54, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bellis, M.; Fogel, E.L.; Sherman, S.; Watkins, J.L.; Chappo, J.; Younger, C.; Cramer, H.; Lehman, G.A. Influence of stricture dilation and repeat brushing on the cancer detection rate of brush cytology in the evaluation of malignant biliary obstruction. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2003, 58, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurzawinski, T.R.; Deery, A.; Dooley, J.S.; Dick, R.; Hobbs, K.E.; Davidson, B.R. A prospective study of biliary cytology in 100 patients with bile duct strictures. Hepatology 1993, 18, 1399–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okuno, M.; Mukai, T.; Iwata, K.; Watanabe, N.; Tanaka, T.; Iwasa, T.; Shimojo, K.; Ohashi, Y.; Takagi, A.; Ito, Y.; et al. Evaluation of the Cell Block Method Using Overnight-Stored Bile for Malignant Biliary Stricture Diagnosis. Cancers 2022, 14, 2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, D.Y.; Ruth He, A.; Qin, S.; Chen, L.T.; Okusaka, T.; Vogel, A.; Kim, J.W.; Suksombooncharoen, T.; Lee, M.A.; Kitano, M.; et al. Durvalumab plus Gemcitabine and Cisplatin in Advanced Biliary Tract Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. Evid. 2022, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamarca, A.; Palmer, D.H.; Wasan, H.S.; Ross, P.J.; Ma, Y.T.; Arora, A.; Falk, S.; Gillmore, R.; Wadsley, J.; Patel, K.; et al. Second-line FOLFOX chemotherapy versus active symptom control for advanced biliary tract cancer (ABC-06): A phase 3, open-label, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021, 22, 690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doebele, R.C.; Drilon, A.; Paz-Ares, L.; Siena, S.; Shaw, A.T.; Farago, A.F.; Blakely, C.M.; Seto, T.; Cho, B.C.; Tosi, D.; et al. Entrectinib in patients with advanced or metastatic NTRK fusion-positive solid tumours: Integrated analysis of three phase 1-2 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abou-Alfa, G.K.; Sahai, V.; Hollebecque, A.; Vaccaro, G.; Melisi, D.; Al-Rajabi, R.; Paulson, A.S.; Borad, M.J.; Gallinson, D.; Murphy, A.G.; et al. Pemigatinib for previously treated, locally advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma: A multicentre, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, L.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; Hollebecque, A.; Valle, J.W.; Morizane, C.; Karasic, T.B.; Abrams, T.A.; Furuse, J.; Kelley, R.K.; Cassier, P.A.; et al. Futibatinib for FGFR2-Rearranged Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marabelle, A.; Fakih, M.; Lopez, J.; Shah, M.; Shapira-Frommer, R.; Nakagawa, K.; Chung, H.C.; Kindler, H.L.; Lopez-Martin, J.A.; Miller, W.H., Jr.; et al. Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: Prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1353–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diaz, L.A., Jr.; Shiu, K.K.; Kim, T.W.; Jensen, B.V.; Jensen, L.H.; Punt, C.; Smith, D.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Benavides, M.; Gibbs, P.; et al. Pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy for microsatellite instability-high or mismatch repair-deficient metastatic colorectal cancer (KEYNOTE-177): Final analysis of a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2022, 23, 659–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCCN Guidelines, version 2; Biliary Tract Cancers; NCCN Guidelines: Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA, 2023.

- Moeini, A.; Haber, P.K.; Sia, D. Cell of origin in biliary tract cancers and clinical implications. JHEP Rep. 2021, 3, 100226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, A.; Incorvaia, L.; Capoluongo, E.; Tagliaferri, P.; Gori, S.; Cortesi, L.; Genuardi, M.; Turchetti, D.; De Giorgi, U.; Di Maio, M.; et al. Implementation of preventive and predictive BRCA testing in patients with breast, ovarian, pancreatic, and prostate cancer: A position paper of Italian Scientific Societies. ESMO Open 2022, 7, 100459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, H.; Arai, Y.; Totoki, Y.; Shirota, T.; Elzawahry, A.; Kato, M.; Hama, N.; Hosoda, F.; Urushidate, T.; Ohashi, S.; et al. Genomic spectra of biliary tract cancer. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arechederra, M.; Rullán, M.; Amat, I.; Oyon, D.; Zabalza, L.; Elizalde, M.; Latasa, M.U.; Mercado, M.R.; Ruiz-Clavijo, D.; Saldaña, C.; et al. Next-generation sequencing of bile cell-free DNA for the early detection of patients with malignant biliary strictures. Gut 2022, 71, 1141–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marabelle, A.; Le, D.T.; Ascierto, P.A.; Di Giacomo, A.M.; De Jesus-Acosta, A.; Delord, J.P.; Geva, R.; Gottfried, M.; Penel, N.; Hansen, A.R.; et al. Efficacy of Pembrolizumab in Patients with Noncolorectal High Microsatellite Instability/Mismatch Repair-Deficient Cancer: Results from the Phase II KEYNOTE-158 Study. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Case No. | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | F | F | M |

| Age, years | 70 | 76 | 76 |

| T-Bil, mg/dL | 17.2 | 12.8 | 0.8 |

| CA 19-9, U/mL | 95.7 | 620.3 | 10 |

| Location of stricture | Distal | Distal | Distal |

| Malignant biliary obstruction length, mm | 43 | 23 | 14 |

| Volume of collected bile, mL | 100 | 180 | 200 |

| Malignant cell number of Cell block specimen, n | 2785 | 1024 | 200 |

| Pathological diagnosis | Distal cholangiocarcinoma | Distal cholangiocarcinoma | Distal cholangiocarcinoma |

| UICC Stage | IB | IB | IIA |

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CB1 | SRS1 | CB2 | SRS2 | CB3 | SRS3 | ||||

| Extracted DNA | |||||||||

| DNA consentration, ng/µL | 66.6 | 182.7 | 10.3 | 110.6 | 4.1 | 163.0 | |||

| DNA amount, ng | 2665.3 | 7309.0 | 413.3 | 4424.0 | 162.7 | 6521.3 | |||

| A260/A280 | 1.883 | 1.903 | 1.887 | 2.087 | 1.730 | 1.997 | |||

| A260/A230 | 1.990 | 0.843 | 1.153 | 0.595 | 0.280 | 2.080 | |||

| Total number of reads in NGS, n | 94,673,584 | 90,863,546 | 95,077,806 | 102,191,580 | 81,323,720 | 93,161,788 | |||

| Mean x0.4 coverage | 96.6 | 92.7 | 96.5 | 94.9 | 96.3 | 95.3 | |||

| Extracted RNA | |||||||||

| RNA consentration, ng/µL | 49.1 | 415.1 | 18.3 | 297.8 | 6.7 | 231.2 | |||

| RNA amount, ng | 982.0 | 8301.3 | 366.7 | 5956.7 | 160.8 | 5548.0 | |||

| A260/A280 | 1.807 | 1.837 | 1.810 | 2.043 | 1.620 | 2.023 | |||

| A260/A230 | 1.380 | 1.580 | 1.666 | 2.113 | 0.953 | 2.167 | |||

| Total reads of reads NGS, n | 22,101,328 | 9,345,634 | 24,342,318 | 24,806,180 | 19,600,362 | 25,684,972 | |||

| Mean coverage | 2508.0 | 411.2 | 4616.1 | 4743.1 | 2780.0 | 4963.1 | |||

| DNA analysis | p-value | p-value | p-value | ||||||

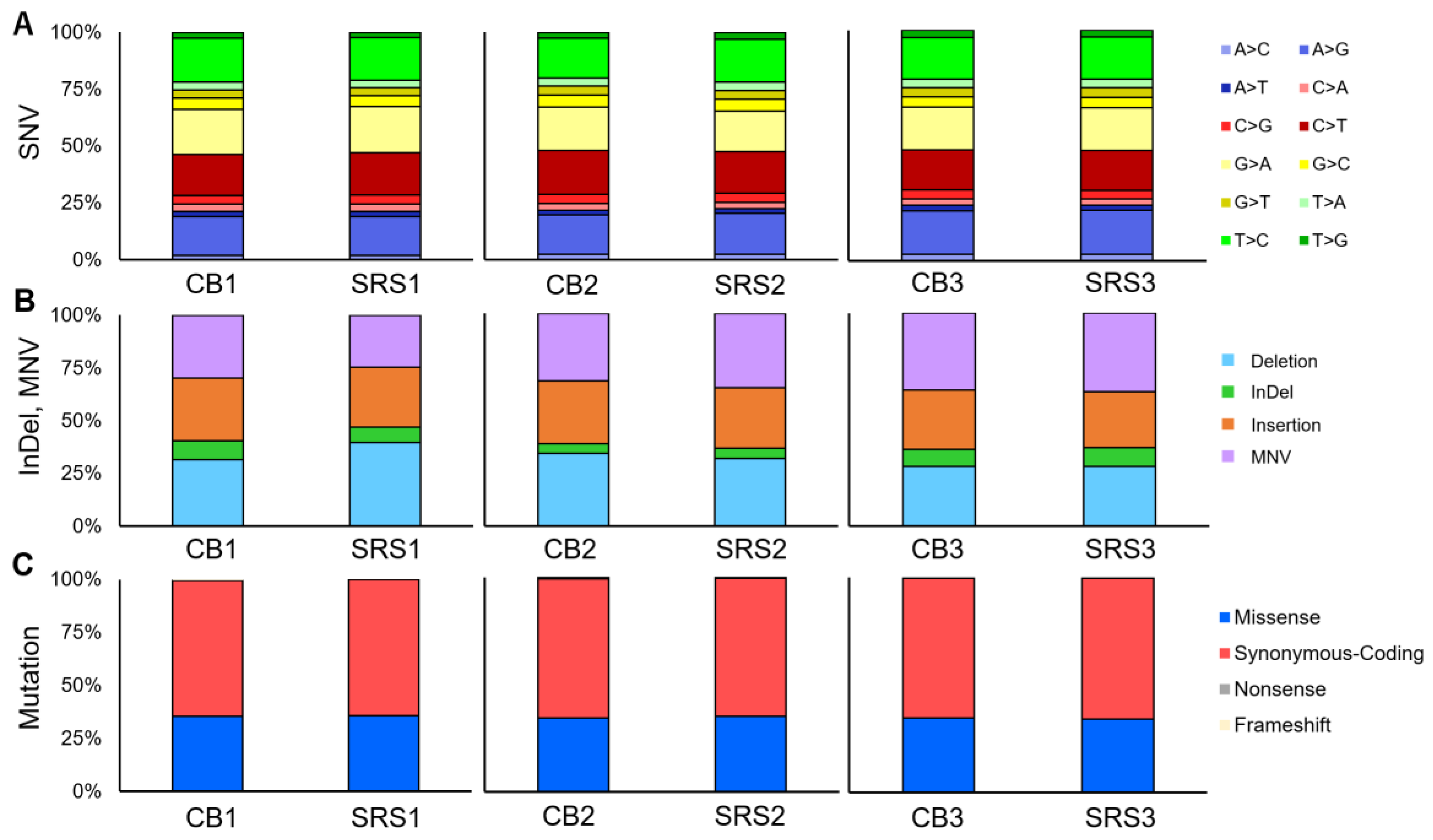

| SNV, n (%) | 1111 (100%) | 1126 (100%) | 1485 (100%) | 1097 (100%) | 1041 (100%) | 1041 (100%) | |||

| A>C | 21 (1.9%) | 21 (1.9%) | 1.0 | 36 (2.4%) | 26 (2.4%) | 1.0 | 28 (2.7%) | 29 (2.8%) | 1.0 |

| A>G | 189 (17.0%) | 191 (17.0%) | 1.0 | 255 (17.2%) | 197 (18.0%) | 0.60 | 198 (19.0%) | 199 (19.1%) | 0.91 |

| A>T | 25 (2.2%) | 26 (2.3%) | 1.0 | 32 (2.2%) | 22 (2.0%) | 0.89 | 24 (2.3%) | 23 (2.2%) | 1.0 |

| C>A | 35 (3.2%) | 36 (3.2%) | 1.0 | 42 (2.8%) | 30 (2.7%) | 0.90 | 30 (2.9%) | 28 (2.7%) | 0.89 |

| C>G | 44 (4.0%) | 46 (4.0%) | 0.91 | 62 (4.2%) | 45 (4.1%) | 1.0 | 39 (3.7%) | 39 (3.7%) | 1.0 |

| C>T | 201 (18.1%) | 208 (18.5%) | 0.83 | 286 (19.3%) | 201 (18.3%) | 0.58 | 182 (17.5%) | 180 (17.3%) | 0.95 |

| G>A | 219 (19.7%) | 229 (20.3%) | 0.75 | 284 (19.1%) | 197(18.0%) | 0.47 | 193 (18.5%) | 193 (18.5%) | 1.0 |

| G>C | 55 (5.0%) | 54 (4.8%) | 0.92 | 78 (5.2%) | 58 (5.3%) | 0.93 | 46 (4.4%) | 46 (4.4%) | 1.0 |

| G>T | 41 (3.7%) | 40 (3.6%) | 0.91 | 61 (4.1%) | 41 (3.7%) | 0.68 | 43 (4.1%) | 45 (4.3%) | 0.91 |

| T>A | 38 (3.4%) | 36 (3.2%) | 0.81 | 50 (3.4%) | 41 (3.7%) | 0.67 | 37 (3.6%) | 38 (3.7%) | 1.0 |

| T>C | 215 (19.3%) | 212 (18.8%) | 0.79 | 262 (17.6%) | 207 (18.9%) | 0.44 | 189 (18.2%) | 191 (18.4%) | 0.95 |

| T>G | 28 (2.5%) | 27 (2.4%) | 0.89 | 37 (2.5%) | 32 (2.9%) | 0.54 | 32 (3.1%) | 30 (2.9%) | 0.90 |

| InDel, MNV, n (%) | 72 (100%) | 93 (100%) | p-value | 91 (100%) | 64 (100%) | p-value | 88 (100%) | 66 (100%) | p-value |

| Deletion | 21 (29.2%) | 32 (34.4%) | 0.51 | 30 (33.0%) | 20 (31.2%) | 0.86 | 19 (21.6%) | 17 (25.7%) | 0.57 |

| Insertion | 20 (27.8%) | 23 (24.7%) | 0.72 | 26 (28.5%) | 18 (28.1%) | 1.0 | 34 (38.6%) | 18 (27.3%) | 0.17 |

| InDel | 6 (8.3%) | 18 (19.4%) | 0.07 | 7 (7.7%) | 4 (6.3%) | 1.0 | 8 (9.1%) | 6 (9.1%) | 1.0 |

| MNV | 25 (34.7%) | 20 (21.5%) | 0.08 | 28 (30.8%) | 22 (34.4%) | 0.73 | 27 (30.7%) | 25 (37.9%) | 0.39 |

| Mutation, n (%) | 235 (100%) | 235 (100%) | p-value | 262 (100%) | 225 (100%) | p-value | 231 (100%) | 229 (100%) | p-value |

| Missense | 83 (35.3%) | 84 (35.7%) | 1.0 | 90 (34.3%) | 79 (35.1%) | 0.92 | 80 (34.6%) | 78 (34.1%) | 0.92 |

| Synonymous-Coding | 151 (64.3%) | 151 (64.3%) | 1.0 | 170 (64.9%) | 145 (64.4%) | 0.92 | 150 (64.9%) | 150 (65.5%) | 0.92 |

| Nonsense | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | N.A. | 2 (0.8%) | 1 (0.5%) | 1.0 | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0.50 |

| Frameshift | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) | 1.0 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | N.A. | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0%) | 0.50 |

| CNV, n | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Percent unstable MSI sites | 1.67 | 0.90 | 1.61 | 2.40 | 12.5 | 2.44 | |||

| Total TMB | 2.35 | 9.48 | 8.60 | 2.35 | 0 | 1.56 | |||

| RNA analysis | |||||||||

| Number of splice variant, n | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Number of fusion, n | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CB1 | SRS1 | CB2 | SRS2 | CB3 | SRS3 | ||||

| Short variant | |||||||||

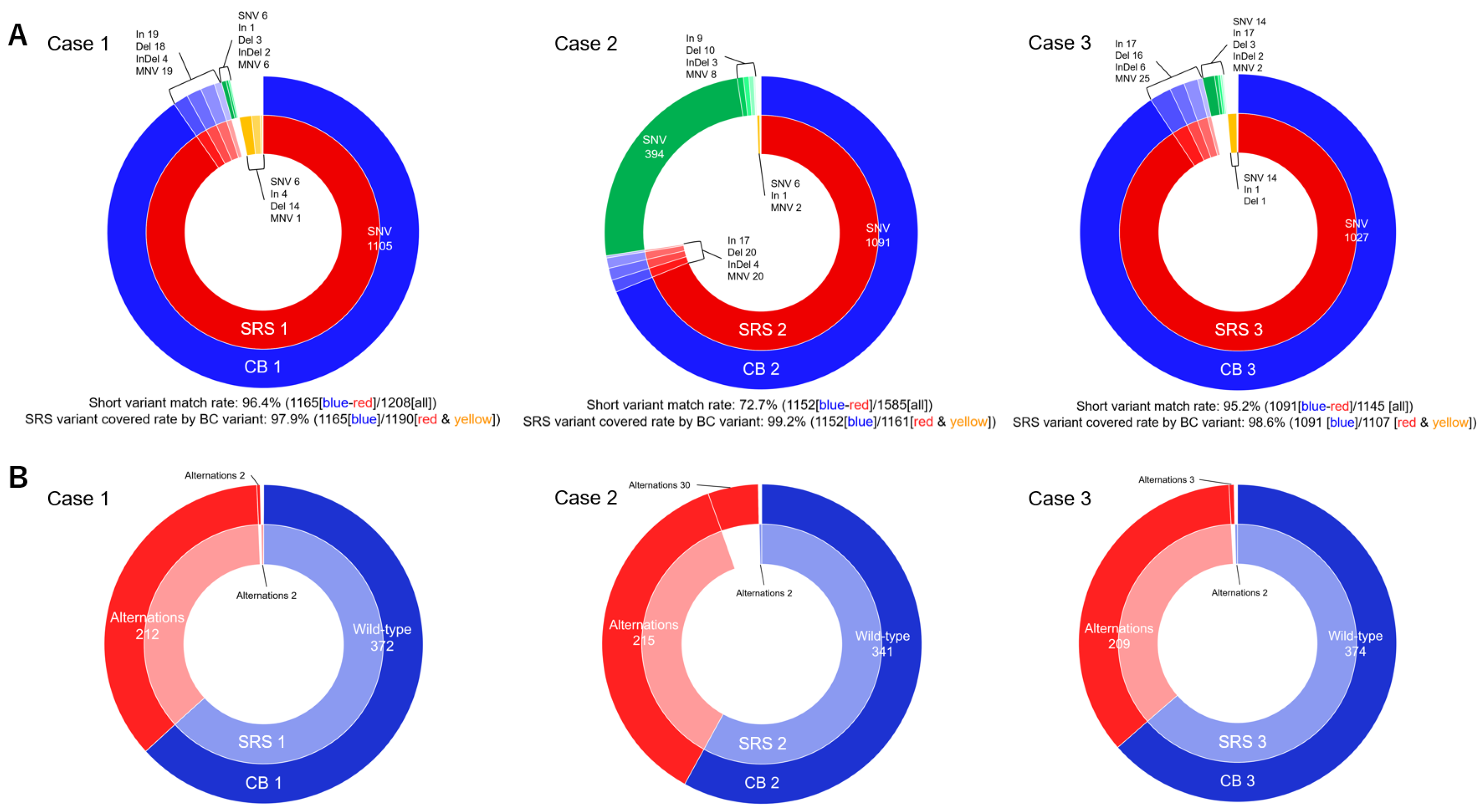

| Total number of short variant, n | 1183 | 1219 | 1576 | 1161 | 1129 | 1107 | |||

| Number of unmatched short variant, n | 18 | 25 | 424 | 9 | 38 | 16 | |||

| Short variant matched rate, % | 96.4% | 72.7% | 95.2% | ||||||

| SRS variant covered rate by CB variant, % | 97.9% | 99.2% | 98.6% | ||||||

| Total evaluated genetic alternation in TSO 500 (n = 588) | p-value | p-value | p-value | ||||||

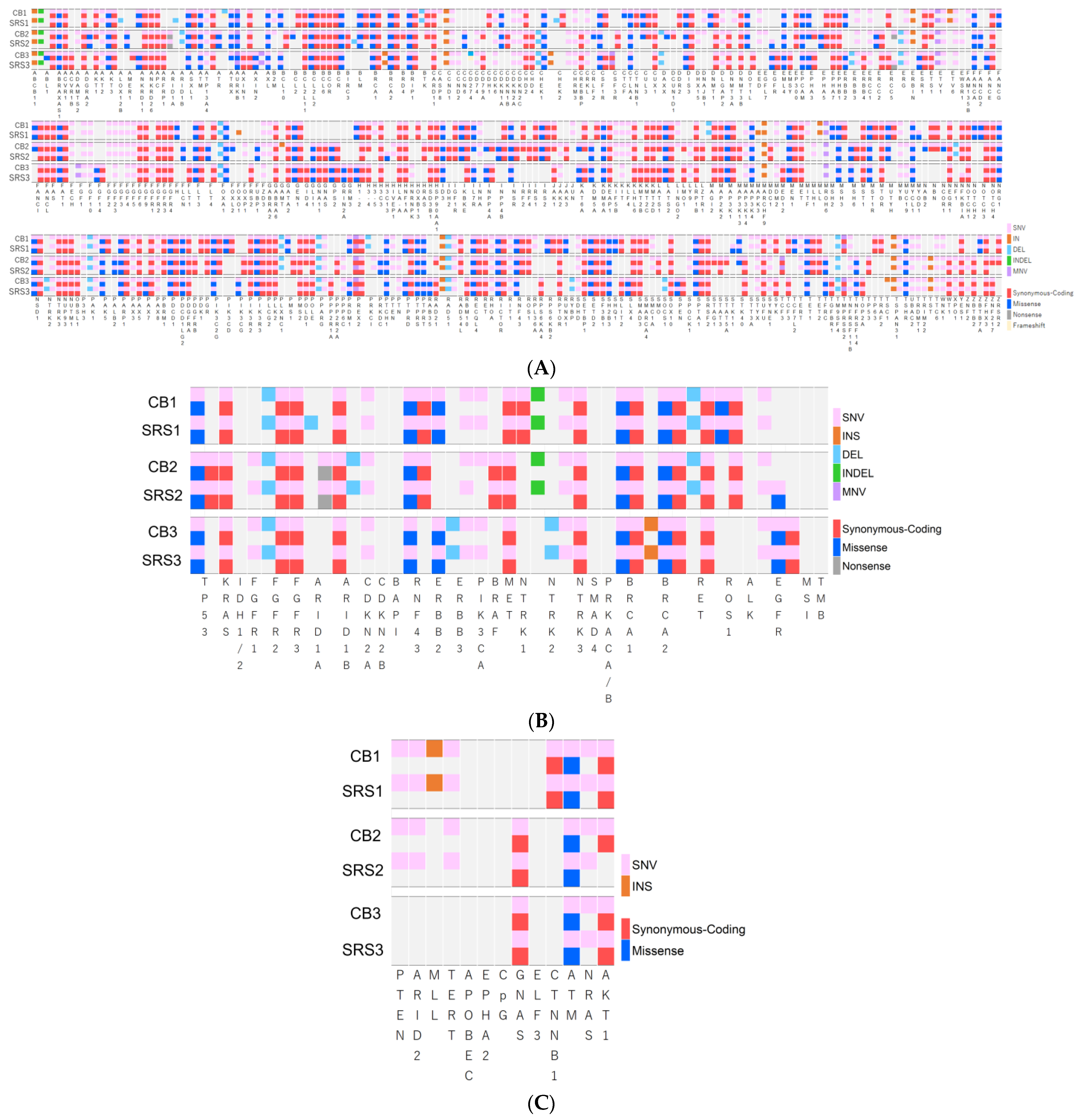

| Number of genetic alteration, n (%) | 214 (36.4%) | 214 (36.4%) | 1.0 | 245 (41.7%) | 217 (36.9%) | 0.11 | 212 (36.1%) | 211 (35.9%) | 1.0 |

| Number of unmatched genetic alteration, n | 2 | 2 | 2 | 30 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Gene matched rate, % | 97.6% | 89.5% | 98.1% | ||||||

| SRS gene covered rate by CB gene, % | 99.7% | 99.6% | 99.7% | ||||||

| Druggable or cancer-related genetic alternation (n = 43) | p-value | p-value | p-value | ||||||

| Number of genetic alteration, n (%) | 27 (62.8%) | 28 (65.1%) | 1.0 | 27 (62.8%) | 26 (60.5%) | 0.83 | 22 (51.2%) | 22 (51.2%) | 1.0 |

| Number of unmatched genetic alteration, n | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Gene matched rate, % | 97.7% | 97.7% | 100% | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Okuno, M.; Kanayama, T.; Iwata, K.; Tanaka, T.; Tomita, H.; Iwasa, Y.; Shirakami, Y.; Watanabe, N.; Mukai, T.; Tomita, E.; et al. Possibility of Cell Block Specimens from Overnight-Stored Bile for Next-Generation Sequencing of Cholangiocarcinoma. Cells 2024, 13, 925. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13110925

Okuno M, Kanayama T, Iwata K, Tanaka T, Tomita H, Iwasa Y, Shirakami Y, Watanabe N, Mukai T, Tomita E, et al. Possibility of Cell Block Specimens from Overnight-Stored Bile for Next-Generation Sequencing of Cholangiocarcinoma. Cells. 2024; 13(11):925. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13110925

Chicago/Turabian StyleOkuno, Mitsuru, Tomohiro Kanayama, Keisuke Iwata, Takuji Tanaka, Hiroyuki Tomita, Yuhei Iwasa, Yohei Shirakami, Naoki Watanabe, Tsuyoshi Mukai, Eiichi Tomita, and et al. 2024. "Possibility of Cell Block Specimens from Overnight-Stored Bile for Next-Generation Sequencing of Cholangiocarcinoma" Cells 13, no. 11: 925. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13110925

APA StyleOkuno, M., Kanayama, T., Iwata, K., Tanaka, T., Tomita, H., Iwasa, Y., Shirakami, Y., Watanabe, N., Mukai, T., Tomita, E., & Shimizu, M. (2024). Possibility of Cell Block Specimens from Overnight-Stored Bile for Next-Generation Sequencing of Cholangiocarcinoma. Cells, 13(11), 925. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells13110925