Circulating Tumor DNA Testing for Minimal Residual Disease and Its Application in Colorectal Cancer

Abstract

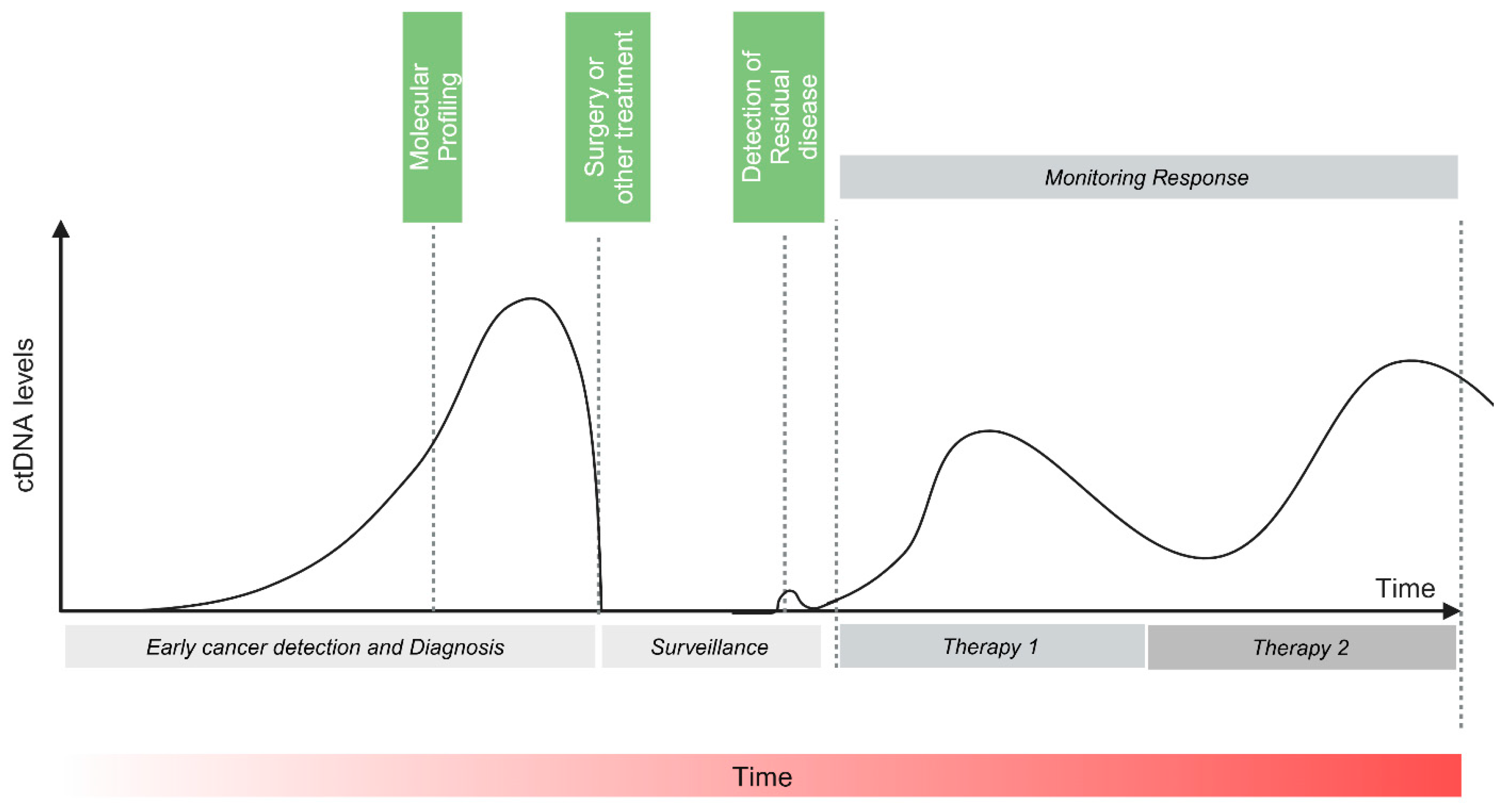

1. Introduction

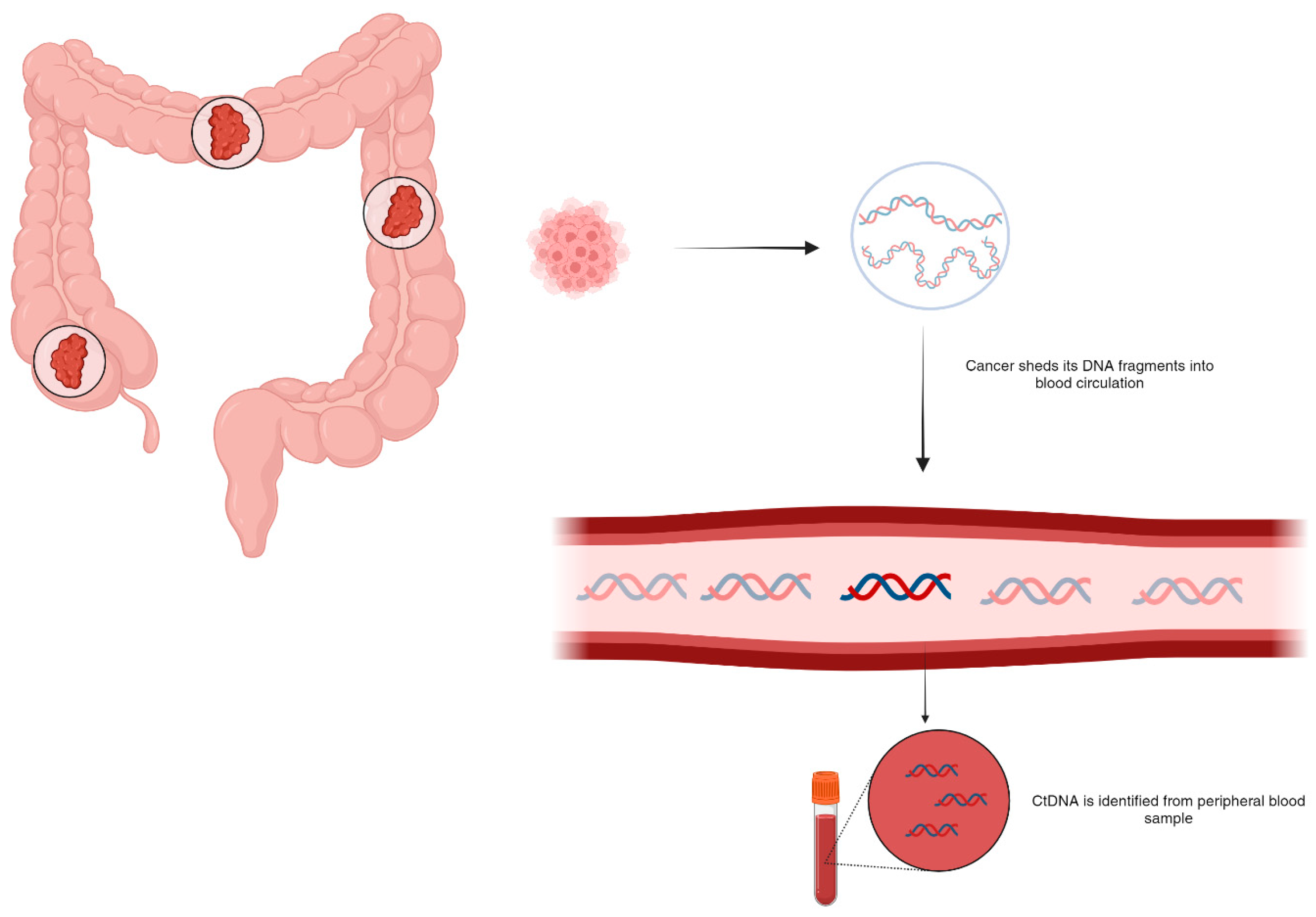

2. Circulating DNA

3. ctDNA Assays

4. ctDNA-Based Detection of MRD and Prognostication in Colorectal Cancer

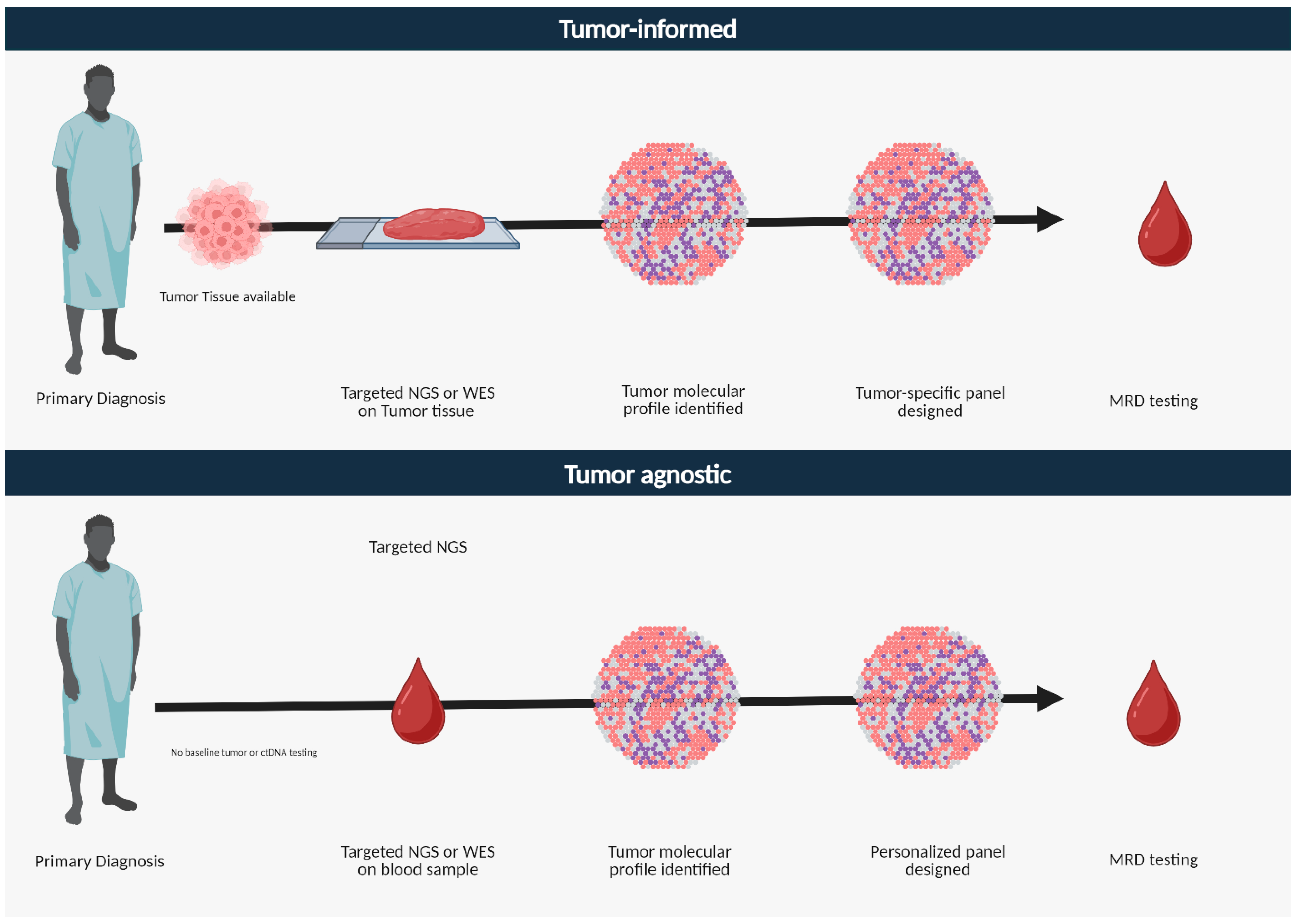

4.1. Studies Using Tumor-Informed Approach

4.2. Studies Using Tumor-Agnostic Approach

| Author | Number of Subjects and Disease Stage | ctDNA Assay | CtDNA Testing and Surveillance | Median Follow-Up (Months) | Major Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tie et al. [16] | 230 with stage II colorectal cancer | Safe-SeqS | 4–10 weeks postoperative followed by every 3 months for up to 2 years | 27 | Postoperative ctDNA presence was associated with a 79% recurrence rate at 27 months, compared to 10% for ctDNA-negative patients, and ctDNA detection preceded radiological recurrence by over 5 months—enabling earlier intervention. |

| Tie et al., 2019 [15] | 96 patients with stage III colon cancer | Safe-SeqS | Serial plasma monitoring 4–10 weeks postoperative and within 6 weeks of ACT completion | 28.9 | Postsurgical cohort, ctDNA positivity was linked to an HR of 3.8 (95% CI: 2.4–21.0, p < 0.001), and in the post-ACT group, an HR of 6.8 (95% CI: 11.0–157.0, p < 0.001). Three-year RFS for ctDNA-positive vs. ctDNA-negative patients was 30% vs. 77% post-ACT, and 47% vs. 76% post surgery. ctDNA positivity after surgery had a higher HR for recurrence (3.8) than elevated CEA levels (HR 3.4). |

| Tie et al., 2019 [47] | 159 patients with locally advanced rectal cancer | Safe-SeqS | Pretreatment, post treatment CRT, and 4–10 weeks after surgery | 24 | After CRT, ctDNA positivity was associated with an HR of 6.6 (p < 0.001), and post surgery, an HR of 13.0 (p < 0.001). Three-year RFS was 33% in ctDNA-positive patients post surgery compared to 87% in ctDNA-negative patients. |

| Tie et al., 2021 [48] | 54 patients with CRC with liver metastasis | SafeSeqS | Samples were collected preoperatively, postoperatively, serially during pre and postoperative chemotherapy, and during follow-up | 51 | Patients with detectable postoperative ctDNA had significantly lower RFS (HR 6.3; 95% CI: 2.58–15.2; p < 0.001) and OS (HR 4.2; 95% CI: 1.5–11.8; p < 0.001). Detection of ctDNA at the end of treatment correlated with a 5-year RFS of 0%, compared to 75.6% in those without ctDNA (HR 14.9; 95% CI: 4.94–44.7; p < 0.001). |

| DYNAMIC STUDY Tie et al., 2022 [56] | 455 patients with stage II CC | SafeSeqS | 4 and 7 weeks post surgery | 37 | Adjuvant chemotherapy was administered less frequently in the ctDNA-guided group (15%) than in standard management (28%). Two-year RFS was 86.4% in ctDNA-positive patients who received adjuvant therapy, compared to 92.5% in ctDNA-negative patients without it. ctDNA-guided management showed noninferiority to standard management (93.5% vs. 92.4%; absolute difference: 1.1 percentage points; 95% CI: −4.1 to 6.2). |

| Reinert et al., 2019 [45] | 130 patients with stage I to III CRC | Signatera | Preop, postop day 30, and every 3 months for up to 3 years | 12.5 | 30-day postoperative ctDNA-positive patients had a 7-fold higher relapse risk than ctDNA-negative patients (HR 7.2; 95% CI: 2.7–19.0; p < 0.001). After completing ACT, ctDNA positivity was linked to a 17-fold higher relapse risk (HR 17.5; 95% CI: 5.4–56.5; p < 0.001), and during post-therapy surveillance, ctDNA-positive patients were 40 times more likely to experience recurrence (HR 43.5; 95% CI: 9.8–193.5; p < 0.001). Serial ctDNA monitoring detected recurrence up to 16.5 months earlier than imaging (mean: 8.7 months; range: 0.8–16.5 months). |

| Loupakis et al., 2021 [57] | 112 patients with CRC undergoing liver resection | Signatera | Postoperative, at the time of radiologic relapse or last follow-up | 10.7 | Postsurgical MRD positivity was detected in 54.4% of patients (61/112), with 96.7% of these (59/61) progressing by data cutoff (HR 5.8; 95% CI: 3.5–9.7; p < 0.001). MRD positivity was also linked to poorer overall survival (HR 16.0; 95% CI: 3.9–68.0; p < 0.001), and ctDNA-MRD status emerged as the strongest prognostic factor for DFS (HR 5.78; 95% CI: 3.34–10.0; p < 0.001). |

| Henriksen et al., 2022 [49] | 168 patients with stage III CRC | Signatera | 2–4 weeks postop and every 3 months thereafter | 35 | Postoperative ctDNA detection strongly predicted recurrence (HR 7.0; 95% CI: 3.7–13.5), with an even higher risk immediately post ACT (HR 50.76; 95% CI: 15.4–167). Serial ctDNA monitoring post treatment was similarly predictive (HR 50.80; 95% CI: 14.9–172; p < 0.001). Additionally, ctDNA growth rate correlated with survival outcomes (HR 2.7; 95% CI: 1.1–6.7; p = 0.039) and indicated recurrence at a median of 9.8 months ahead of radiologic imaging. |

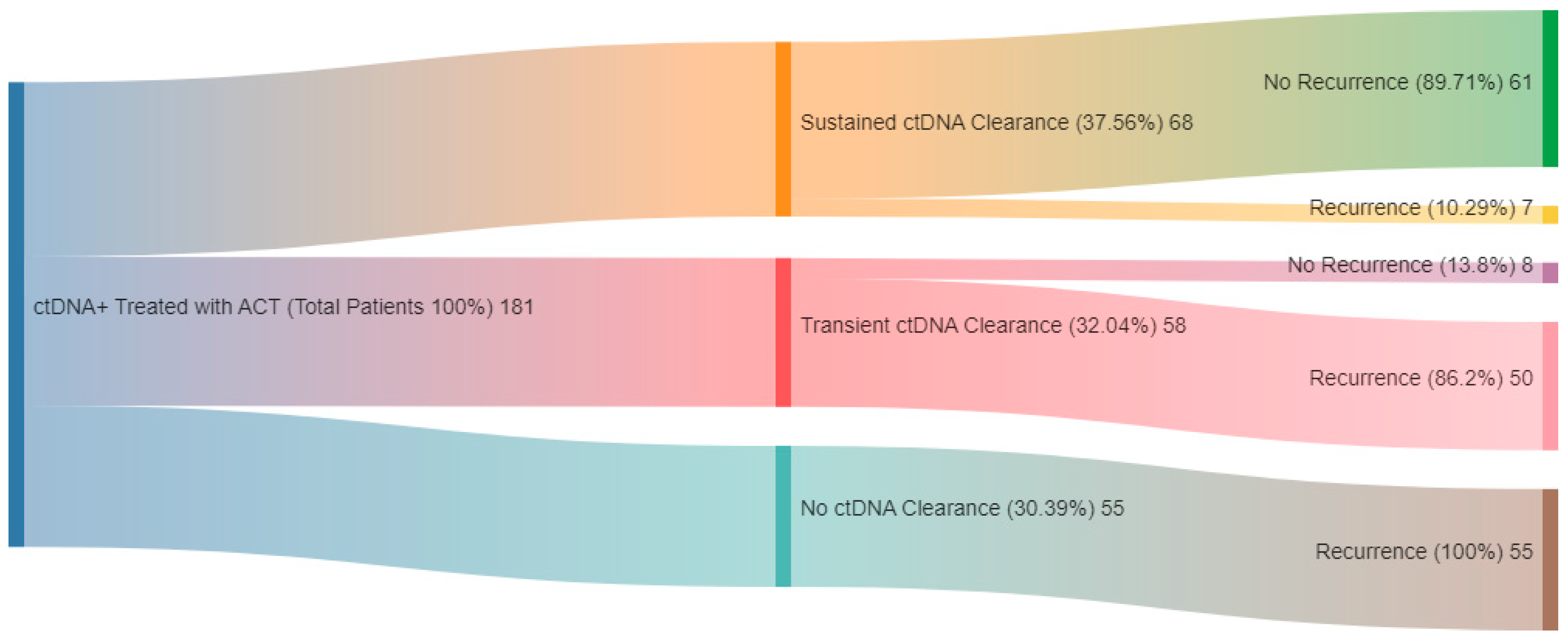

| GALAXY Kotani et al., 2024 [58] | 2240 stages II–IV CRC patients | Signatera | Before surgery, 1-month postoperatively and every 3 months thereafter for 2 years | 23 | ctDNA positivity during the MRD window was associated with significantly poorer DFS (HR 11.99; p < 0.0001) and OS (HR 9.68; p < 0.0001). Among patients who recurred, ctDNA positivity correlated with reduced OS (HR 2.71; p < 0.0001). MRD-positive patients had consistently shorter DFS across biomarker subsets. Sustained ctDNA clearance after ACT indicated better outcomes compared to transient clearance (24-month DFS: 89.0% vs. 3.3%; 24-month OS: 100.0% vs. 82.3%). True spontaneous clearance without recurrence was observed in only 1.9% (2/105) |

| Tarazona et al., 2019 [50] | 150 patients with stages I to III CC | Tumor-informed ddPCR | Preoperative, 6–8 weeks postoperative, and every 4 months up to 5 years | 24.7 | Postoperative ctDNA was linked to poorer DFS (HR 6.96; p = 0.0001), and remained the only significant predictor after multivariable adjustment (HR 11.64; 95% CI: 3.67–36.88; p < 0.001). ctDNA positivity post chemotherapy also indicated reduced DFS (HR 10.02; 95% CI: 9.202–307.3; p < 0.0001). ctDNA detection during surveillance predicted recurrence with a median lead time of 11.5 months over radiologic imaging. |

| McDuff et al., 2021 [51] | 29 patients with locally advanced rectal carcinoma | ddPCR | Baseline, preoperative, and postoperative | 20 | Detectable postoperative ctDNA was linked to poorer RFS (HR 11.56; p = 0.007). Among patients with undetectable ctDNA, 13.3% (2/15) experienced recurrence, yielding a negative predictive value of 87%. All patients with detectable ctDNA post surgery recurred, resulting in a positive predictive value of 100%. |

| Parikh et al., 2021 [39] | 103 patients with stages I–IV CRC | Tumor-uninformed assay (REVEAL) | Postoperative, post ACT, and longitudinally in some patients | 21.0 | All 15 patients with detectable ctDNA recurred (PPV 100%; HR 11.28; p < 0.0001). By incorporating serial and surveillance samples (within 4 months of recurrence), sensitivity increased to 69% and 91%. Additionally, integrating epigenomic signatures boosted sensitivity by 25–36% compared to genomic alterations alone. |

| Overman et al., 2017 [59] | 54 patients with stage IV CRC with OM | Guardant Health Reveal | Immediately postoperative | 33 | Postoperative ctDNA detection was strongly associated with reduced RFS (p = 0.002; HR 3.1; 95% CI: 1.7–9.1), with a 2-year RFS of 0% compared to 47% in ctDNA-negative patients. ctDNA detected recurrence at a median of 5.1 months before radiographic evidence. |

| Lonardi et al. [60] | 69 patients with stage IV CRC | Tissue informed personalized assay (FoundationOne | Preoperative, postoperative, post ACT | NR | MRD positivity was linked to lower DFS (HR 4.97; 95% CI: 2.67–9.24; p < 0.0001) and OS (HR 27.05; 95% CI: 3.60–203.46; p < 0.0001). ctDNA positivity at follow-up significantly reduced DFS (HR 8.78; 95% CI: 3.59–21.49; p < 0.0001) and OS (HR 20.06; 95% CI: 2.51–160.25; p < 0.0001), with a sensitivity of 69% and specificity of 100%. |

| Taieb et al. [61] | 1345 patients with III CRC | ddPCR | Postoperative, prechemotherapy, 3 months, 6 months | 79.2 | 3-year DFS rate was 66.39% for ctDNA-positive patients versus 76.71% for ctDNA-negative patients (p = 0.015). ctDNA was an independent prognostic marker for both DFS (adjusted HR 1.55; 95% CI: 1.13–2.12; p = 0.006) and OS (HR 1.65; 95% CI: 1.12–2.43; p = 0.011), and remained prognostic in patients treated for 3 months or those with T4 and/or N2 tumors. |

| Chee [62] | 52 patients with oligometastatic CRC | Guardant Reveal | Preoperatively, 3 weeks postoperative, and mutiple structured | 12.5 | Of the post-ctDNA positive patients, 23 out of 25 recurred (PPV 92%), while 4 out of 20 ctDNA-negative patients recurred (NPV 80%). Median time to radiographic recurrence was 36 weeks for ctDNA-positive patients, compared to not reached for ctDNA-negative patients (HR 7.7; 95% CI: 2.6–22.5; p < 0.001). |

| Shaobo [63] | Stage I–IV CRC 1138 patients | ColonES assay | Preoperatively, postoperatively 1 month, then 3 months | 36 | Univariate and multivariate analyses identified preoperative ctDNA methylation levels as an independent risk factor for both RFS (HR 2.136; 95% CI: 1.238–3.684; p = 0.006) and OS (HR 2.457; 95% CI: 1.398–4.317; p = 0.002). |

| Shaobo [64] | Stage I to III CRC 299 patients | Postoperatively 1 month, then 3 months | 36 | 1-month postoperatively, ctDNA-positive patients were 17.5 times more likely to relapse than ctDNA-negative patients (HR 17.5; 95% CI: 8.9–34.4; p < 0.001). Following ACT, ctDNA positivity was linked to significantly shorter recurrence-free survival (HR 13.8; 95% CI: 5.9–32.1; p < 0.001). Longitudinally, ctDNA-positive patients had poorer RFS than ctDNA-negative ones (HR 20.6; 95% CI: 9.5–44.9; p < 0.001), with ctDNA detecting CRC recurrence at a median of 3.3 months before radiologic confirmation. |

5. Role of ctDNA in Evaluating the Efficacy of Adjuvant Therapy in CRC

6. Role of ctDNA in Surveillance

7. ctDNA: Current Applicability

| Study Identifier | Study Phase | Population | Number | Ct DNA Assay | Study Description | Primary Endpoint |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAREME: NCT05699746 [76] | Phase III | Resected stage I or II CRC | 38 | MInerVa MRD assay | Arm A: ctdNA-positive treatment arm receives CAPEOX for 6 months. Arm B: ctDNA positive, receives no chemotherapy but on active surveillance. | 18-month recurrence-free survival |

| CORRECT-MRDII: NCT05210283 [77] | Prospective observational | Resected stage II or III CRC | 750 | Bespoke | Serial ctDNA monitoring after surgery and ACT if received. | Association of post-definitive therapy and pre-recurrence follow-up ctDNA positivity with recurrence-free survival by stage and cancer type |

| MARIA trial: NCT05219734 [78] | Prospective observational | Stage II–IV with curative intent | Un- known | Invitae personal- ized cancer monitor- ing test | 24-month recurrence risk | |

| NRG-G1008; CIRCULATE-NOR-TH AMERICA NCT0517416 [79] | II/III | Stage II and III CC | 1912 | Signatera | Cohort A: Arm 1—ctDNA negative treated with CAPOX or FOLFOX for 3–6months. Arm 2—ctDNA negative on surveillance with serial ctDNA and no treatment. Cohort B: Arm 3—ctDNA positive treated with CAPOX or FOLFOX for 6 months. Arm 4—ctDNA positive treated with FOLFIRINOX for 6 months. | Time to ctDNA-positive status and disease-free survival |

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2024. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, X.; Pengfei, X. Global colorectal cancer burden in 2020 and projections to 2040. Transl. Oncol. 2021, 14, 101174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, T.; Argiles, G.; Oki, E.; Martinelli, E.; Taniguchi, H.; Arnold, D.; Mishima, S.; Li, Y.; Smruti, B.K.; Ahn, J.B.; et al. Pan-Asian adapted ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the diagnosis treatment and follow-up of patients with localised colon cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, 1496–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Network, N.C.C. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Colon Cancer (Version 5.2024). 2024. Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Guraya, S.Y. Pattern, Stage, and Time of Recurrent Colorectal Cancer After Curative Surgery. Clin. Color. Cancer 2019, 18, e223–e228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobrero, A.; Grothey, A.; Iveson, T.; Labianca, R.; Yoshino, T.; Taieb, J.; Maughan, T.; Buyse, M.; Andre, T.; Meyerhardt, J.; et al. The hard road to data interpretation: 3 or 6 months of adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage III colon cancer? Ann. Oncol. 2018, 29, 1099–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobrero, A.F.; Puccini, A.; Shi, Q.; Grothey, A.; Andre, T.; Shields, A.F.; Souglakos, I.; Yoshino, T.; Iveson, T.; Ceppi, M.; et al. A new prognostic and predictive tool for shared decision making in stage III colon cancer. Eur. J. Cancer 2020, 138, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mattos-Arruda, L.; Mayor, R.; Ng, C.K.Y.; Weigelt, B.; Martinez-Ricarte, F.; Torrejon, D.; Oliveira, M.; Arias, A.; Raventos, C.; Tang, J.; et al. Cerebrospinal fluid-derived circulating tumour DNA better represents the genomic alterations of brain tumours than plasma. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, S.J.; Tsui, D.W.; Murtaza, M.; Biggs, H.; Rueda, O.M.; Chin, S.F.; Dunning, M.J.; Gale, D.; Forshew, T.; Mahler-Araujo, B.; et al. Analysis of circulating tumor DNA to monitor metastatic breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1199–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murtaza, M.; Dawson, S.J.; Pogrebniak, K.; Rueda, O.M.; Provenzano, E.; Grant, J.; Chin, S.F.; Tsui, D.W.Y.; Marass, F.; Gale, D.; et al. Multifocal clonal evolution characterized using circulating tumour DNA in a case of metastatic breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal-Hanjani, M.; Wilson, G.A.; Horswell, S.; Mitter, R.; Sakarya, O.; Constantin, T.; Salari, R.; Kirkizlar, E.; Sigurjonsson, S.; Pelham, R.; et al. Detection of ubiquitous and heterogeneous mutations in cell-free DNA from patients with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2016, 27, 862–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mattos-Arruda, L.; Weigelt, B.; Cortes, J.; Won, H.H.; Ng, C.K.Y.; Nuciforo, P.; Bidard, F.C.; Aura, C.; Saura, C.; Peg, V.; et al. Capturing intra-tumor genetic heterogeneity by de novo mutation profiling of circulating cell-free tumor DNA: A proof-of-principle. Ann. Oncol. 2014, 25, 1729–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.M.; Bratman, S.V.; To, J.; Wynne, J.F.; Eclov, N.C.; Modlin, L.A.; Liu, C.L.; Neal, J.W.; Wakelee, H.A.; Merritt, R.E.; et al. An ultrasensitive method for quantitating circulating tumor DNA with broad patient coverage. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faulkner, L.G.; Howells, L.M.; Pepper, C.; Shaw, J.A.; Thomas, A.L. The utility of ctDNA in detecting minimal residual disease following curative surgery in colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Cancer 2023, 128, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tie, J.; Cohen, J.D.; Wang, Y.; Christie, M.; Simons, K.; Lee, M.; Wong, R.; Kosmider, S.; Ananda, S.; McKendrick, J.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Analyses as Markers of Recurrence Risk and Benefit of Adjuvant Therapy for Stage III Colon Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 1710–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, J.; Wang, Y.; Tomasetti, C.; Li, L.; Springer, S.; Kinde, I.; Silliman, N.; Tacey, M.; Wong, H.L.; Christie, M.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA analysis detects minimal residual disease and predicts recurrence in patients with stage II colon cancer. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 346ra392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larribere, L.; Martens, U.M. Advantages and Challenges of Using ctDNA NGS to Assess the Presence of Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) in Solid Tumors. Cancers 2021, 13, 5698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valukas, C.; Chawla, A. Measuring response to neoadjuvant therapy using biomarkers in pancreatic cancer: A narrative review. Chin. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 11, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasi, P.M.; Budde, G.; Krainock, M.; Aushev, V.N.; Koyen Malashevich, A.; Malhotra, M.; Olshan, P.; Billings, P.R.; Aleshin, A. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) serial analysis during progression on PD-1 blockade and later CTLA-4 rescue in patients with mismatch repair deficient metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10, e003312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parseghian, C.M.; Loree, J.M.; Morris, V.K.; Liu, X.; Clifton, K.K.; Napolitano, S.; Henry, J.T.; Pereira, A.A.; Vilar, E.; Johnson, B.; et al. Anti-EGFR-resistant clones decay exponentially after progression: Implications for anti-EGFR re-challenge. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbini, M.; Marisi, G.; Azzali, I.; Bartolini, G.; Chiadini, E.; Capelli, L.; Tedaldi, G.; Angeli, D.; Canale, M.; Molinari, C.; et al. Dynamic Monitoring of Circulating Tumor DNA in Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2023, 7, e2200694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.C.M.; Massie, C.; Garcia-Corbacho, J.; Mouliere, F.; Brenton, J.D.; Caldas, C.; Pacey, S.; Baird, R.; Rosenfeld, N. Liquid biopsies come of age: Towards implementation of circulating tumour DNA. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahr, S.; Hentze, H.; Englisch, S.; Hardt, D.; Fackelmayer, F.O.; Hesch, R.D.; Knippers, R. DNA fragments in the blood plasma of cancer patients: Quantitations and evidence for their origin from apoptotic and necrotic cells. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 1659–1665. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moss, J.; Magenheim, J.; Neiman, D.; Zemmour, H.; Loyfer, N.; Korach, A.; Samet, Y.; Maoz, M.; Druid, H.; Arner, P.; et al. Comprehensive human cell-type methylation atlas reveals origins of circulating cell-free DNA in health and disease. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 5068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, L.A., Jr.; Bardelli, A. Liquid biopsies: Genotyping circulating tumor DNA. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adalsteinsson, V.A.; Ha, G.; Freeman, S.S.; Choudhury, A.D.; Stover, D.G.; Parsons, H.A.; Gydush, G.; Reed, S.C.; Rotem, D.; Rhoades, J.; et al. Scalable whole-exome sequencing of cell-free DNA reveals high concordance with metastatic tumors. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diehl, F.; Schmidt, K.; Choti, M.A.; Romans, K.; Goodman, S.; Li, M.; Thornton, K.; Agrawal, N.; Sokoll, L.; Szabo, S.A.; et al. Circulating mutant DNA to assess tumor dynamics. Nat. Med. 2008, 14, 985–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merker, J.D.; Oxnard, G.R.; Compton, C.; Diehn, M.; Hurley, P.; Lazar, A.J.; Lindeman, N.; Lockwood, C.M.; Rai, A.J.; Schilsky, R.L.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Analysis in Patients with Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology and College of American Pathologists Joint Review. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 1631–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouliere, F.; Rosenfeld, N. Circulating tumor-derived DNA is shorter than somatic DNA in plasma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 3178–3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, P.; Lo, Y.M.D. The Long and Short of Circulating Cell-Free DNA and the Ins and Outs of Molecular Diagnostics. Trends Genet. 2016, 32, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Park, K.U. Clinical Circulating Tumor DNA Testing for Precision Oncology. Cancer Res. Treat. 2023, 55, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, F.; Su, L.; Qian, C. Circulating tumor DNA: A promising biomarker in the liquid biopsy of cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 48832–48841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caroli, J.; Sorrentino, G.; Forcato, M.; Del Sal, G.; Bicciato, S. GDA, a web-based tool for Genomics and Drugs integrated analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, W148–W156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherer, F. Capturing Tumor Heterogeneity and Clonal Evolution by Circulating Tumor DNA Profiling. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2020, 215, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nong, J.; Gong, Y.; Guan, Y.; Yi, X.; Yi, Y.; Chang, L.; Yang, L.; Lv, J.; Guo, Z.; Jia, H.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA analysis depicts subclonal architecture and genomic evolution of small cell lung cancer. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitzer, E.; Haque, I.S.; Roberts, C.E.S.; Speicher, M.R. Current and future perspectives of liquid biopsies in genomics-driven oncology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019, 20, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moding, E.J.; Nabet, B.Y.; Alizadeh, A.A.; Diehn, M. Detecting Liquid Remnants of Solid Tumors: Circulating Tumor DNA Minimal Residual Disease. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 2968–2986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettegowda, C.; Sausen, M.; Leary, R.J.; Kinde, I.; Wang, Y.; Agrawal, N.; Bartlett, B.R.; Wang, H.; Luber, B.; Alani, R.M.; et al. Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 224ra224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parikh, A.R.; Van Seventer, E.E.; Siravegna, G.; Hartwig, A.V.; Jaimovich, A.; He, Y.; Kanter, K.; Fish, M.G.; Fosbenner, K.D.; Miao, B.; et al. Minimal Residual Disease Detection using a Plasma-only Circulating Tumor DNA Assay in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 5586–5594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinde, S.; Saxena, S.; Dixit, V.; Tiwari, A.K.; Vishvakarma, N.K.; Shukla, D. Epigenetic Modifiers and Their Potential Application in Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy. Crit. Rev. Oncog. 2020, 25, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heitzer, E. Circulating Tumor DNA for Modern Cancer Management. Clin. Chem. 2020, 66, 143–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbosh, C.; Swanton, C.; Birkbak, N.J. Clonal haematopoiesis: A source of biological noise in cell-free DNA analyses. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 358–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jan, M.; Ebert, B.L.; Jaiswal, S. Clonal hematopoiesis. Semin. Hematol. 2017, 54, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolton, K.L.; Ptashkin, R.N.; Gao, T.; Braunstein, L.; Devlin, S.M.; Kelly, D.; Patel, M.; Berthon, A.; Syed, A.; Yabe, M.; et al. Cancer therapy shapes the fitness landscape of clonal hematopoiesis. Nat. Genet. 2020, 52, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinert, T.; Henriksen, T.V.; Christensen, E.; Sharma, S.; Salari, R.; Sethi, H.; Knudsen, M.; Nordentoft, I.; Wu, H.T.; Tin, A.S.; et al. Analysis of Plasma Cell-Free DNA by Ultradeep Sequencing in Patients with Stages I to III Colorectal Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2019, 5, 1124–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, J.; Cohen, J.D.; Lo, S.N.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Christie, M.; Lee, M.; Wong, R.; Kosmider, S.; Skinner, I.; et al. Prognostic significance of postsurgery circulating tumor DNA in nonmetastatic colorectal cancer: Individual patient pooled analysis of three cohort studies. Int. J. Cancer 2021, 148, 1014–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tie, J.; Cohen, J.D.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Christie, M.; Simons, K.; Elsaleh, H.; Kosmider, S.; Wong, R.; Yip, D.; et al. Serial circulating tumour DNA analysis during multimodality treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer: A prospective biomarker study. Gut 2019, 68, 663–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, J.; Wang, Y.; Cohen, J.; Li, L.; Hong, W.; Christie, M.; Wong, H.L.; Kosmider, S.; Wong, R.; Thomson, B.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA dynamics and recurrence risk in patients undergoing curative intent resection of colorectal cancer liver metastases: A prospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henriksen, T.V.; Tarazona, N.; Frydendahl, A.; Reinert, T.; Gimeno-Valiente, F.; Carbonell-Asins, J.A.; Sharma, S.; Renner, D.; Hafez, D.; Roda, D.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA in Stage III Colorectal Cancer, beyond Minimal Residual Disease Detection, toward Assessment of Adjuvant Therapy Efficacy and Clinical Behavior of Recurrences. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarazona, N.; Gimeno-Valiente, F.; Gambardella, V.; Zuniga, S.; Rentero-Garrido, P.; Huerta, M.; Rosello, S.; Martinez-Ciarpaglini, C.; Carbonell-Asins, J.A.; Carrasco, F.; et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing of circulating-tumor DNA for tracking minimal residual disease in localized colon cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1804–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDuff, S.G.R.; Hardiman, K.M.; Ulintz, P.J.; Parikh, A.R.; Zheng, H.; Kim, D.W.; Lennerz, J.K.; Hazar-Rethinam, M.; Van Seventer, E.E.; Fetter, I.J.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Predicts Pathologic and Clinical Outcomes Following Neoadjuvant Chemoradiation and Surgery for Patients with Locally Advanced Rectal Cancer. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2021, 5, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, Y.; Watanabe, J.; Akazawa, N.; Hirata, K.; Kataoka, K.; Yokota, M.; Kato, K.; Kotaka, M.; Kagawa, Y.; Yeh, K.H.; et al. ctDNA-based molecular residual disease and survival in resectable colorectal cancer. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 3272–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yukami, H.; Nakamura, Y.; Mishima, S.; Ando, K.; Bando, H.; Watanabe, J.; Hirata, K.; Akazawa, N.; Ikeda, M.; Yokota, M.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) dynamics in patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) with molecular residual disease: Updated analysis from GALAXY study in the CIRCULATE-JAPAN. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42 (Suppl. S3), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinari, C.; Marisi, G.; Laliotis, G.; Spickard, E.; Rapposelli, I.G.; Petracci, E.; George, G.V.; Dutta, P.; Sharma, S.; Malhotra, M.; et al. Assessment of circulating tumor DNA in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer treated with neoadjuvant therapy. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 29536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, Y.; Tsukada, Y.; Matsuhashi, N.; Murano, T.; Shiozawa, M.; Takahashi, Y.; Oki, E.; Goto, M.; Kagawa, Y.; Kanazawa, A.; et al. Colorectal Cancer Recurrence Prediction Using a Tissue-Free Epigenomic Minimal Residual Disease Assay. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 4377–4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, J.; Cohen, J.D.; Lahouel, K.; Lo, S.N.; Wang, Y.; Kosmider, S.; Wong, R.; Shapiro, J.; Lee, M.; Harris, S.; et al. Circulating Tumor DNA Analysis Guiding Adjuvant Therapy in Stage II Colon Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022, 386, 2261–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loupakis, F.; Sharma, S.; Derouazi, M.; Murgioni, S.; Biason, P.; Rizzato, M.D.; Rasola, C.; Renner, D.; Shchegrova, S.; Koyen Malashevich, A.; et al. Detection of Molecular Residual Disease Using Personalized Circulating Tumor DNA Assay in Patients with Colorectal Cancer Undergoing Resection of Metastases. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2021, 5, 1166–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotani, D.; Oki, E.; Nakamura, Y.; Yukami, H.; Mishima, S.; Bando, H.; Shirasu, H.; Yamazaki, K.; Watanabe, J.; Kotaka, M.; et al. Molecular residual disease and efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with colorectal cancer. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Overman, M.J.; Vauthey, J.-N.; Aloia, T.A.; Conrad, C.; Chun, Y.S.; Pereira, A.A.L.; Jiang, Z.; Crosby, S.; Wei, S.; Raghav, K.P.S.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) utilizing a high-sensitivity panel to detect minimal residual disease post liver hepatectomy and predict disease recurrence. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 35 (Suppl. S15), 3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonardi, S.; Nimeiri, H.S.; Xu, C.; Zollinger, D.R.; Madison, R.W.; Fine, A.; Gjoerup, O.V.; Rasola, C.; Angerilli, V.; Sharma, S.; et al. Comprehensive Genomic Profiling (CGP)-Informed Personalized Molecular Residual Disease (MRD) Detection: An Exploratory Analysis from the PREDATOR Study of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer (mCRC) Patients Undergoing Surgical Resection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taieb, J.; Taly, V.; Henriques, J.; Bourreau, C.; Mineur, L.; Bennouna, J.; Desramé, J.; Louvet, C.; Lepère, C.; Mabro, M.; et al. Prognostic Value and Relation with Adjuvant Treatment Duration of ctDNA in Stage III Colon Cancer: A Post Hoc Analysis of the PRODIGE-GERCOR IDEA-France Trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 27, 5638–5646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chee, B.; Ibrahim, F.; Esquivel, M.; Seventer, E.E.V.; Jarnagin, J.X.; Zhang, L.; Ju, J.H.; Price, K.S.; Raymond, V.M.; Corvera, C.U.; et al. Circulating tumor derived cell-free DNA (ctDNA) to predict recurrence of metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) following curative intent surgery or radiation. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39 (Suppl. S15), 3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, S.; Dai, W.; Wang, H.; Lan, X.; Ma, C.; Su, Z.; Xiang, W.; Han, L.; Luo, W.; Zhang, L.; et al. Early detection and prognosis prediction for colorectal cancer by circulating tumour DNA methylation haplotypes: A multicentre cohort study. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 55, 101717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mo, S.; Ye, L.; Wang, D.; Han, L.; Zhou, S.; Wang, H.; Dai, W.; Wang, Y.; Luo, W.; Wang, R.; et al. Early Detection of Molecular Residual Disease and Risk Stratification for Stage I to III Colorectal Cancer via Circulating Tumor DNA Methylation. JAMA Oncol. 2023, 9, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tie, J.; Wang, Y.; Lo, S.N.; Lahouel, K.; Cohen, J.D.; Wong, R.; Shapiro, J.D.; Harris, S.J.; Khattak, A.; Burge, M.E.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA analysis guiding adjuvant therapy in stage II colon cancer: Overall survival and updated 5-year results from the randomized DYNAMIC trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42 (Suppl. S16), 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockelman, C.; Engelmann, B.E.; Kaprio, T.; Hansen, T.F.; Glimelius, B. Risk of recurrence in patients with colon cancer stage II and III: A systematic review and meta-analysis of recent literature. Acta Oncol. 2015, 54, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, T.; de Gramont, A.; Vernerey, D.; Chibaudel, B.; Bonnetain, F.; Tijeras-Raballand, A.; Scriva, A.; Hickish, T.; Tabernero, J.; Van Laethem, J.L.; et al. Adjuvant Fluorouracil, Leucovorin, and Oxaliplatin in Stage II to III Colon Cancer: Updated 10-Year Survival and Outcomes According to BRAF Mutation and Mismatch Repair Status of the MOSAIC Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 33, 4176–4187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, V.K.; Yothers, G.; Kopetz, S.; Puhalla, S.L.; Lucas, P.C.; Iqbal, A.; Boland, P.M.; Deming, D.A.; Scott, A.J.; Lim, H.J.; et al. Phase II results of circulating tumor DNA as a predictive biomarker in adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with stage II colon cancer: NRG-GI005 (COBRA) phase II/III study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42 (Suppl. S3), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, M.; Loree, J.M.; Kasi, P.M.; Parikh, A.R. Using Circulating Tumor DNA in Colorectal Cancer: Current and Evolving Practices. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 2846–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasi, P.M.; Aushev, V.N.; Ensor, J.; Langer, N.; Wang, C.G.; Cannon, T.L.; Berim, L.D.; Feinstein, T.; Grothey, A.; McCollom, J.W.; et al. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) for informing adjuvant chemotherapy (ACT) in stage II/III colorectal cancer (CRC): Interim analysis of BESPOKE CRC study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42 (Suppl. S3), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, B.D.; Shinkins, B.; Pathiraja, I.; Roberts, N.W.; James, T.J.; Mallett, S.; Perera, R.; Primrose, J.N.; Mant, D. Blood CEA levels for detecting recurrent colorectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD011134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, M.; Gibbs, P. Caution is required before recommending routine carcinoembryonic antigen and imaging follow-up for patients with early-stage colon cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, e279–e280; author reply e281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCT03803553: Identification and Treatment of Micrometastatic Disease in Stage III Colon Cancer. 20 March 2024. Available online: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT03803553 (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- NCT04457297: Initial Attack on Latent Metastasis Using TAS-102 for ct DNA Identified Colorectal Cancer Patients After Curative Resection (ALTAIR). 18 November 2022. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04457297 (accessed on 26 October 2024).

- Henriksen, T.V.; Reinert, T.; Rasmussen, M.H.; Demuth, C.; Love, U.S.; Madsen, A.H.; Gotschalck, K.A.; Iversen, L.H.; Andersen, C.L. Comparing single-target and multitarget approaches for postoperative circulating tumour DNA detection in stage II-III colorectal cancer patients. Mol. Oncol. 2022, 16, 3654–3665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, K.-F.; Xiao, Q.; Xiang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Song, J.; Xu, Y.; Huang, X.-F.; Chen, M.; Du, J.; Jin, K.; et al. A randomized controlled trial of CAPEOX vs observation in patients with early-stage colorectal cancer with positive MRD after curative surgery (CAREME). J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42 (Suppl. S3), TPS225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCT05210283: CORRECT Study of Minimal Residual Disease Detection in Colorectal Cancer (MRD). 02 February 2023. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05210283 (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Esplin, E.D.; Swan, K.; Ifhar, L.; Heald, B.; Nielsen, S.M.; Alvarez, D.E.P.; O’Callaghan, W.D.; Daber, R.; Ross, D.; Vieira, C.; et al. MRD assay to evaluate recurrence and response via a tumor informed assessment: MARIA-Colorectal Cancer Observational trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42 (Suppl. S3), TPS242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieu, C.H.; Yu, G.; Kopetz, S.; Puhalla, S.L.; Lucas, P.C.; Sahin, I.H.; Deming, D.A.; Philip, P.A.; Hong, T.S.; Rojas-Khalil, Y.; et al. NRG-GI008: Colon adjuvant chemotherapy based on evaluation of residual disease (CIRCULATE-NORTH AMERICA). J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 42 (Suppl. S3), TPS243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Tumor Informed | Tumor Agnostic | |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Focuses on mutations associated with a given patient’s tumor | Sequences cfDNA without any information about the patient’s tumor genomics |

| Genetic Coverage | Limited customized panel of genes based on patient’s tumor | Broad panel of commonly altered genes |

| Assay used | Cancer-specific targeted panels | Broad NGS panels, whole exome/genome sequencing |

| Tissue sequencing | Required | Not required |

| Screening germline, CHIP alterations | Yes | No (it actually filters for CHIP and germline genes) |

| Turnaround time | Longer period due to tissue sequencing; 3–4 weeks | Shorter, takes 1–2 weeks |

| Pros | Higher sensitivity for expected variants | Detects novel and unexpected variants |

| Cons | Potential to miss atypical mutations; higher cost implications | Variable sensitivity and specificity |

| Applications | Detect MRD Assess treatment response Serial testing for recurrence monitoring | Detect MRD Determine heterogeneity Identify actionable alterations and drivers of resistance Serial testing for disease monitoring |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abidoye, O.; Ahn, D.H.; Borad, M.J.; Wu, C.; Bekaii-Saab, T.; Chakrabarti, S.; Sonbol, M.B. Circulating Tumor DNA Testing for Minimal Residual Disease and Its Application in Colorectal Cancer. Cells 2025, 14, 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14030161

Abidoye O, Ahn DH, Borad MJ, Wu C, Bekaii-Saab T, Chakrabarti S, Sonbol MB. Circulating Tumor DNA Testing for Minimal Residual Disease and Its Application in Colorectal Cancer. Cells. 2025; 14(3):161. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14030161

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbidoye, Oluseyi, Daniel H. Ahn, Mitesh J. Borad, Christina Wu, Tanios Bekaii-Saab, Sakti Chakrabarti, and Mohamad Bassam Sonbol. 2025. "Circulating Tumor DNA Testing for Minimal Residual Disease and Its Application in Colorectal Cancer" Cells 14, no. 3: 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14030161

APA StyleAbidoye, O., Ahn, D. H., Borad, M. J., Wu, C., Bekaii-Saab, T., Chakrabarti, S., & Sonbol, M. B. (2025). Circulating Tumor DNA Testing for Minimal Residual Disease and Its Application in Colorectal Cancer. Cells, 14(3), 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells14030161