The Emerging Role of MicroRNAs in NAFLD: Highlight of MicroRNA-29a in Modulating Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Beyond

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. MiRs as Markers in Liver Disease

| microRNA | Expression | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| miR-21 | Up | [64] |

| miR-33 | Up | [62] |

| miR-34a | Up | [61,63,64,76] |

| miR-103/107 | Up | [77] |

| miR-122 | Up | [29,59,60,61,63,76] |

| miR-132 | Down | [78] |

| miR-146b | Down | [78,79] |

| miR-148a | Down | [80,81] |

| miR-181a | Up | [82,83,84] |

| miR-181d | Down | [79] |

| miR-192 | Up | [59,60,63] |

| miR-197 | Down | [79] |

| miR-221/222 | Up | [65,85] |

| miR-375 | Up | [59] |

| miR-802 | Up | [66] |

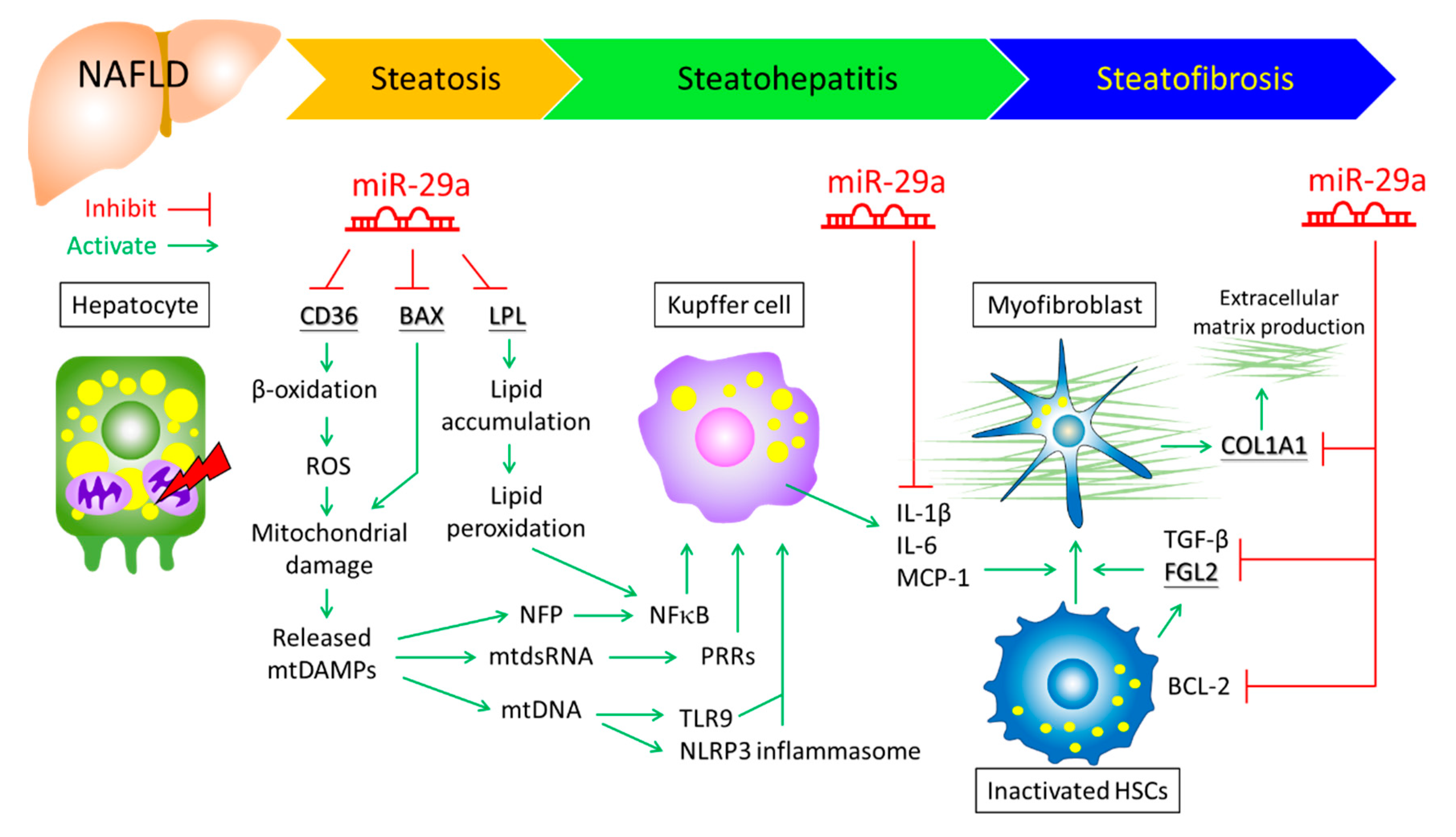

3. MiR-29a Functions as an Epigenetic Modifier to Mitigate Liver Injury

4. Role of miR-29a in Oxidative Stress and Inflammation

5. Role of miR-29a in Mitochondrial Metabolism

6. MiRNAs Involved in Lipid Metabolism of NALFD

7. The Role of miR-29a in Fibrogenesis

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rinella, M.E. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review. JAMA 2015, 313, 2263–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, Y.; Yang, B.; Qiu, W.; Hao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, B.; Li, N.; Cheng, S.; Lin, Z.; Rui, Y.C.; et al. ER-residential Nogo-B accelerates NAFLD-associated HCC mediated by metabolic reprogramming of oxLDL lipophagy. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Hadi, H.; Di Vincenzo, A.; Vettor, R.; Rossato, M. Cardio-Metabolic Disorders in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lombardi, R.; Fargion, S.; Fracanzani, A.L. Brain involvement in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): A systematic review. Dig. Liver Dis. 2019, 51, 1214–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Park, J.S.; Roh, Y.S. Molecular insights into the role of mitochondria in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2019, 42, 935–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leveille, M.; Estall, J.L. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in the Transition from NASH to HCC. Metabolites 2019, 9, 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stavast, C.J.; Erkeland, S.J. The Non-Canonical Aspects of MicroRNAs: Many Roads to Gene Regulation. Cells 2019, 8, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004, 116, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xiao, M.; Li, J.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Wu, F.; Xi, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ding, C.; Luo, H.; Li, Y.; et al. MicroRNAs activate gene transcription epigenetically as an enhancer trigger. RNA Biol. 2017, 14, 1326–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.; Ajay, S.S.; Yook, J.I.; Kim, H.S.; Hong, S.H.; Kim, N.H.; Dhanasekaran, S.M.; Chinnaiyan, A.M.; Athey, B.D. New class of microRNA targets containing simultaneous 5′-UTR and 3′-UTR interaction sites. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 1175–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fabbri, M.; Paone, A.; Calore, F.; Galli, R.; Croce, C.M. A new role for microRNAs, as ligands of Toll-like receptors. RNA Biol. 2013, 10, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fabbri, M.; Paone, A.; Calore, F.; Galli, R.; Gaudio, E.; Santhanam, R.; Lovat, F.; Fadda, P.; Mao, C.; Nuovo, G.J.; et al. MicroRNAs bind to Toll-like receptors to induce prometastatic inflammatory response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, E2110–E2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Das, S.; Bedja, D.; Campbell, N.; Dunkerly, B.; Chenna, V.; Maitra, A.; Steenbergen, C. miR-181c regulates the mitochondrial genome, bioenergetics, and propensity for heart failure in vivo. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e96820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gjorgjieva, M.; Sobolewski, C.; Dolicka, D.; Correia de Sousa, M.; Foti, M. miRNAs and NAFLD: From pathophysiology to therapy. Gut. 2019, 68, 2065–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vienberg, S.; Geiger, J.; Madsen, S.; Dalgaard, L.T. MicroRNAs in metabolism. Acta Physiol. 2017, 219, 346–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.H.; Yang, Y.L.; Wang, F.S. The Role of miR-29a in the Regulation, Function, and Signaling of Liver Fibrosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kriegel, A.J.; Liu, Y.; Fang, Y.; Ding, X.; Liang, M. The miR-29 family: Genomics, cell biology, and relevance to renal and cardiovascular injury. Physiol. Genom. 2012, 44, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, M.; Jakel, L.; Bruinsma, I.B.; Claassen, J.A.; Kuiperij, H.B.; Verbeek, M.M. MicroRNA-29a Is a Candidate Biomarker for Alzheimer’s Disease in Cell-Free Cerebrospinal Fluid. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 2894–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goh, S.Y.; Chao, Y.X.; Dheen, S.T.; Tan, E.K.; Tay, S.S. Role of MicroRNAs in Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Huang, J.; Song, G.; Yin, Z.; Fu, Z.; Ye, Z. MiR-29a and Messenger RNA Expression of Bone Turnover Markers in Canonical Wnt Pathway in Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis. Clin. Lab. 2017, 63, 955–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.Q.; Cai, A.P.; Chen, J.Y.; Huang, C.; Li, J.; Feng, Y.Q. The Relationship of Plasma miR-29a and Oxidized Low Density Lipoprotein with Atherosclerosis. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 40, 1521–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Qiu, C. Underexpression of CACNA1C Caused by Overexpression of microRNA-29a Underlies the Pathogenesis of Atrial Fibrillation. Med. Sci. Monit. 2016, 22, 2175–2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Afum-Adjei Awuah, A.; Ueberberg, B.; Owusu-Dabo, E.; Frempong, M.; Jacobsen, M. Dynamics of T-cell IFN-gamma and miR-29a expression during active pulmonary tuberculosis. Int. Immunol. 2014, 26, 579–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, J.A.; Stroud, R.E.; O’Quinn, E.C.; Black, L.E.; Barth, J.L.; Elefteriades, J.A.; Bavaria, J.E.; Gorman, J.H., 3rd; Gorman, R.C.; Spinale, F.G.; et al. Selective microRNA suppression in human thoracic aneurysms: Relationship of miR-29a to aortic size and proteolytic induction. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2011, 4, 605–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Millar, N.L.; Gilchrist, D.S.; Akbar, M.; Reilly, J.H.; Kerr, S.C.; Campbell, A.L.; Murrell, G.A.C.; Liew, F.Y.; Kurowska-Stolarska, M.; McInnes, I.B. MicroRNA29a regulates IL-33-mediated tissue remodelling in tendon disease. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hsu, Y.C.; Chang, P.J.; Ho, C.; Huang, Y.T.; Shih, Y.H.; Wang, C.J.; Lin, C.L. Protective effects of miR-29a on diabetic glomerular dysfunction by modulation of DKK1/Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 30575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kawashita, Y.; Jinnin, M.; Makino, T.; Kajihara, I.; Makino, K.; Honda, N.; Masuguchi, S.; Fukushima, S.; Inoue, Y.; Ihn, H. Circulating miR-29a levels in patients with scleroderma spectrum disorder. J. Derm. Sci. 2011, 61, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldschmidt, I.; Thum, T.; Baumann, U. Circulating miR-21 and miR-29a as Markers of Disease Severity and Etiology in Cholestatic Pediatric Liver Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2016, 5, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jampoka, K.; Muangpaisarn, P.; Khongnomnan, K.; Treeprasertsuk, S.; Tangkijvanich, P.; Payungporn, S. Serum miR-29a and miR-122 as Potential Biomarkers for Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD). Microrna 2018, 7, 215–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Zheng, J.M.; Cheng, Q.; Yu, K.K.; Ling, Q.X.; Chen, M.Q.; Li, N. Serum microRNA-29 levels correlate with disease progression in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J. Dig. Dis. 2014, 15, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambrecht, J.; Verhulst, S.; Reynaert, H.; van Grunsven, L.A. The miRFIB-Score: A Serological miRNA-Based Scoring Algorithm for the Diagnosis of Significant Liver Fibrosis. Cells 2019, 8, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Roderburg, C.; Urban, G.W.; Bettermann, K.; Vucur, M.; Zimmermann, H.; Schmidt, S.; Janssen, J.; Koppe, C.; Knolle, P.; Castoldi, M.; et al. Micro-RNA profiling reveals a role for miR-29 in human and murine liver fibrosis. Hepatology 2011, 53, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, H.J.; Kim, S.S.; Nam, J.S.; Kim, J.K.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, B.; Wang, H.J.; Kim, B.W.; Lee, J.D.; Kang, D.Y.; et al. Low levels of circulating microRNA-26a/29a as poor prognostic markers in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who underwent curative treatment. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2017, 41, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, D.D.; Yan, W.; Sha, H.H.; Zhao, J.H.; Yang, S.J.; Zhang, H.D.; Hou, J.C.; Xu, H.Z.; et al. MiR-29a: A potential therapeutic target and promising biomarker in tumors. Biosci. Rep. 2018, 38, BSR20171265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhu, H.T.; Dong, Q.Z.; Sheng, Y.Y.; Wei, J.W.; Wang, G.; Zhou, H.J.; Ren, N.; Jia, H.L.; Ye, Q.H.; Qin, L.X. MicroRNA-29a-5p is a novel predictor for early recurrence of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical resection. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e52393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhu, X.C.; Dong, Q.Z.; Zhang, X.F.; Deng, B.; Jia, H.L.; Ye, Q.H.; Qin, L.X.; Wu, X.Z. microRNA-29a suppresses cell proliferation by targeting SPARC in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2012, 30, 1321–1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.L.; Kuo, H.C.; Wang, F.S.; Huang, Y.H. MicroRNA-29a Disrupts DNMT3b to Ameliorate Diet-Induced Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, Y.H.; Kuo, H.C.; Yang, Y.L.; Wang, F.S. MicroRNA-29a is a key regulon that regulates BRD4 and mitigates liver fibrosis in mice by inhibiting hepatic stellate cell activation. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 16, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yang, Y.L.; Wang, F.S.; Li, S.C.; Tiao, M.M.; Huang, Y.H. MicroRNA-29a Alleviates Bile Duct Ligation Exacerbation of Hepatic Fibrosis in Mice through Epigenetic Control of Methyltransferases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, Y.H.; Tiao, M.M.; Huang, L.T.; Chuang, J.H.; Kuo, K.C.; Yang, Y.L.; Wang, F.S. Activation of Mir-29a in Activated Hepatic Stellate Cells Modulates Its Profibrogenic Phenotype through Inhibition of Histone Deacetylases 4. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weidle, U.H.; Schmid, D.; Birzele, F.; Brinkmann, U. MicroRNAs Involved in Metastasis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Target Candidates, Functionality and Efficacy in Animal Models and Prognostic Relevance. Cancer Genom. Proteom. 2020, 17, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, G.; Tian, L.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, K.; Li, S.; Li, T. Antitumor activity of sevoflurane in HCC cell line is mediated by miR-29a-induced suppression of Dnmt3a. J. Cell Biochem. 2019, 120, 18152–18161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Yin, D.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, L.; Li, X.D.; Zhou, Z.J.; Zhou, S.L.; Gao, D.M.; Hu, J.; Jin, C.; et al. MicroRNA-29a induces loss of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine and promotes metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma through a TET-SOCS1-MMP9 signaling axis. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.Y.; Wang, F.S.; Yang, Y.L.; Huang, Y.H. MicroRNA-29a Suppresses CD36 to Ameliorate High Fat Diet-Induced Steatohepatitis and Liver Fibrosis in Mice. Cells 2019, 8, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lin, Y.C.; Wang, F.S.; Yang, Y.L.; Chuang, Y.T.; Huang, Y.H. MicroRNA-29a mitigation of toll-like receptor 2 and 4 signaling and alleviation of obstructive jaundice-induced fibrosis in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 496, 880–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiao, M.M.; Wang, F.S.; Huang, L.T.; Chuang, J.H.; Kuo, H.C.; Yang, Y.L.; Huang, Y.H. MicroRNA-29a protects against acute liver injury in a mouse model of obstructive jaundice via inhibition of the extrinsic apoptosis pathway. Apoptosis 2014, 19, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.H.; Bu, X.; Wang, J.J.; Xie, Y.X. MicroRNA-29-3p Regulates Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression Through NF-kappaB Pathway. Clin. Lab. 2019, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, Y.; Itami, S.; Kuroda, M.; Yoshizato, K.; Kawada, N.; Murakami, Y. MiR-29a Assists in Preventing the Activation of Human Stellate Cells and Promotes Recovery From Liver Fibrosis in Mice. Mol. Ther. 2016, 24, 1848–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xuan, J.; Guo, S.L.; Huang, A.; Xu, H.B.; Shao, M.; Yang, Y.; Wen, W. MiR-29a and miR-652 Attenuate Liver Fibrosis by Inhibiting the Differentiation of CD4+ T Cells. Cell Struct. Funct. 2017, 42, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Song, S.; Sun, K.; Dong, J.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, F.; Liu, H.; Sha, Z.; Mao, J.; Ding, G.; Guo, W.; et al. microRNA-29a regulates liver tumor-initiating cells expansion via Bcl-2 pathway. Exp. Cell Res. 2019, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.H.; Yang, Y.L.; Huang, F.C.; Tiao, M.M.; Lin, Y.C.; Tsai, M.H.; Wang, F.S. MicroRNA-29a mitigation of endoplasmic reticulum and autophagy aberrance counteracts in obstructive jaundice-induced fibrosis in mice. Exp. Biol Med. (Maywood) 2018, 243, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Xiong, Y.; Fang, J.H.; Yun, J.P.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, W.H.; Zhuang, S.M. Effects of microRNA-29 on apoptosis, tumorigenicity, and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2010, 51, 836–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.C.; Wang, F.S.; Yang, Y.L.; Tiao, M.M.; Chuang, J.H.; Huang, Y.H. Microarray Study of Pathway Analysis Expression Profile Associated with MicroRNA-29a with Regard to Murine Cholestatic Liver Injuries. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhu, L.R.; Feng, J.L.; Liu, X.J.; Wang, J.M. LncRNA HULC promots HCC growth by downregulating miR-29. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi 2019, 41, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, S.; Liu, Z.; Xiu, M. MiR-29a suppresses cell proliferation by targeting SIRT1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Biomark. 2018, 22, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, G.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Shan, C.; Ye, L.; Zhang, X. Upregulated microRNA-29a by hepatitis B virus X protein enhances hepatoma cell migration by targeting PTEN in cell culture model. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e19518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, R.C.; Feinbaum, R.L.; Ambros, V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell 1993, 75, 843–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krutzfeldt, J.; Rajewsky, N.; Braich, R.; Rajeev, K.G.; Tuschl, T.; Manoharan, M.; Stoffel, M. Silencing of microRNAs in vivo with ‘antagomirs’. Nature 2005, 438, 685–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirola, C.J.; Fernandez Gianotti, T.; Castano, G.O.; Mallardi, P.; San Martino, J.; Mora Gonzalez Lopez Ledesma, M.; Flichman, D.; Mirshahi, F.; Sanyal, A.J.; Sookoian, S. Circulating microRNA signature in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: From serum non-coding RNAs to liver histology and disease pathogenesis. Gut 2015, 64, 800–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Becker, P.P.; Rau, M.; Schmitt, J.; Malsch, C.; Hammer, C.; Bantel, H.; Mullhaupt, B.; Geier, A. Performance of Serum microRNAs -122, -192 and -21 as Biomarkers in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0142661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cermelli, S.; Ruggieri, A.; Marrero, J.A.; Ioannou, G.N.; Beretta, L. Circulating microRNAs in patients with chronic hepatitis C and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Auguet, T.; Aragones, G.; Berlanga, A.; Guiu-Jurado, E.; Marti, A.; Martinez, S.; Sabench, F.; Hernandez, M.; Aguilar, C.; Sirvent, J.J.; et al. miR33a/miR33b* and miR122 as Possible Contributors to Hepatic Lipid Metabolism in Obese Women with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, X.L.; Pan, Q.; Zhang, R.N.; Shen, F.; Yan, S.Y.; Sun, C.; Xu, Z.J.; Chen, Y.W.; Fan, J.G. Disease-specific miR-34a as diagnostic marker of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in a Chinese population. World J. Gastroenterol 2016, 22, 9844–9852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, H.; Suzuki, K.; Ichino, N.; Ando, Y.; Sawada, A.; Osakabe, K.; Sugimoto, K.; Ohashi, K.; Teradaira, R.; Inoue, T.; et al. Associations between circulating microRNAs (miR-21, miR-34a, miR-122 and miR-451) and non-alcoholic fatty liver. Clin. Chim. Acta 2013, 424, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, T.; Enomoto, M.; Fujii, H.; Sekiya, Y.; Yoshizato, K.; Ikeda, K.; Kawada, N. MicroRNA-221/222 upregulation indicates the activation of stellate cells and the progression of liver fibrosis. Gut 2012, 61, 1600–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, M.; Lv, G.; Wang, G. High Blood miR-802 Is Associated With Poor Prognosis in HCC Patients by Regulating DNA Damage Response 1 (REDD1)-Mediated Function of T Cells. Oncol. Res. 2019, 27, 1025–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Qin, L.; Hu, R. Development and validation of serum exosomal microRNAs as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Cell Biochem. 2019, 120, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.S.; Cho, H.J.; Nam, J.S.; Kim, H.J.; Kang, D.R.; Won, J.H.; Kim, J.; Kim, J.K.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, B.H.; et al. Plasma MicroRNA-21, 26a, and 29a-3p as Predictive Markers for Treatment Response Following Transarterial Chemoembolization in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2018, 33, e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, Z.; Shen, S. Combined low miRNA-29s is an independent risk factor in predicting prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy: A Chinese population-based study. Medicine (Baltim.) 2017, 96, e8795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.T.; Hasan, A.M.; Liu, R.B.; Zhang, Z.C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.Y.; Wang, F.; Shao, J.Y. Serum microRNA profiles as prognostic biomarkers for HBV-positive hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 45637–45648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eguchi, A.; Lazaro, R.G.; Wang, J.; Kim, J.; Povero, D.; Willliams, B.; Ho, S.B.; Starkel, P.; Schnabl, B.; Ohno-Machado, L.; et al. Extracellular vesicles released by hepatocytes from gastric infusion model of alcoholic liver disease contain a MicroRNA barcode that can be detected in blood. Hepatology 2017, 65, 475–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lopez-Riera, M.; Conde, I.; Tolosa, L.; Zaragoza, A.; Castell, J.V.; Gomez-Lechon, M.J.; Jover, R. New microRNA Biomarkers for Drug-Induced Steatosis and Their Potential to Predict the Contribution of Drugs to Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Front. Pharm. 2017, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jia, N.; Lin, X.; Ma, S.; Ge, S.; Mu, S.; Yang, C.; Shi, S.; Gao, L.; Xu, J.; Bo, T.; et al. Amelioration of hepatic steatosis is associated with modulation of gut microbiota and suppression of hepatic miR-34a in Gynostemma pentaphylla (Thunb.) Makino treated mice. Nutr. Metab. (Lond.) 2018, 15, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, J.; Xiao, Y.; Wu, X.; Jiang, L.; Yang, S.; Ding, Z.; Fang, Z.; Hua, H.; Kirby, M.S.; Shou, J. A circulating microRNA signature as noninvasive diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Bmc. Genom. 2018, 19, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, M.X.; Gao, M.; Li, C.Z.; Yu, C.Z.; Yan, H.; Peng, C.; Li, Y.; Li, C.G.; Ma, Z.L.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Dicer1/miR-29/HMGCR axis contributes to hepatic free cholesterol accumulation in mouse non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Acta. Pharm. Sin. 2017, 38, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oses, M.; Margareto Sanchez, J.; Portillo, M.P.; Aguilera, C.M.; Labayen, I. Circulating miRNAs as Biomarkers of Obesity and Obesity-Associated Comorbidities in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Joven, J.; Espinel, E.; Rull, A.; Aragones, G.; Rodriguez-Gallego, E.; Camps, J.; Micol, V.; Herranz-Lopez, M.; Menendez, J.A.; Borras, I.; et al. Plant-derived polyphenols regulate expression of miRNA paralogs miR-103/107 and miR-122 and prevent diet-induced fatty liver disease in hyperlipidemic mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1820, 894–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, R.; Otgonsuren, M.; Younoszai, Z.; Allawi, H.; Raybuck, B.; Younossi, Z. Circulating miRNA in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and coronary artery disease. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016, 3, e000096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celikbilek, M.; Baskol, M.; Taheri, S.; Deniz, K.; Dogan, S.; Zararsiz, G.; Gursoy, S.; Guven, K.; Ozbakir, O. Circulating microRNAs in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J. Hepatol 2014, 6, 613–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babu, K.R.; Muckenthaler, M.U. miR-148a regulates expression of the transferrin receptor 1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, X.R.; He, Y.; Huang, C.; Li, J. MicroRNA-148a is silenced by hypermethylation and interacts with DNA methyltransferase 1 in hepatocellular carcinogenesis. Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 44, 1915–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, R.; Duan, X.; Liu, X.; Cao, H.; Wang, Y.; Fan, J.; Wang, B. Upregulation of miR-181a impairs lipid metabolism by targeting PPARalpha expression in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 508, 1252–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, X.; Yang, Y.; Xu, C.; Peng, Z.; Zhang, M.; Lei, L.; Gao, W.; Dong, Y.; Shi, Z.; Sun, X.; et al. Upregulation of miR-181a impairs hepatic glucose and lipid homeostasis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 91362–91378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryndyak, V.P.; Latendresse, J.R.; Montgomery, B.; Ross, S.A.; Beland, F.A.; Rusyn, I.; Pogribny, I.P. Plasma microRNAs are sensitive indicators of inter-strain differences in the severity of liver injury induced in mice by a choline- and folate-deficient diet. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 2012, 262, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Dongiovanni, P.; Meroni, M.; Longo, M.; Fargion, S.; Fracanzani, A.L. miRNA Signature in NAFLD: A Turning Point for a Non-Invasive Diagnosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2018, 19, 3966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Portela, A.; Esteller, M. Epigenetic modifications and human disease. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanherkar, R.R.; Bhatia-Dey, N.; Csoka, A.B. Epigenetics across the human lifespan. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014, 2, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lind, M.I.; Spagopoulou, F. Evolutionary consequences of epigenetic inheritance. Hered. (Edinb) 2018, 121, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, X.; Li, W.X.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.F.; Li, H.D.; Huang, H.M.; Bu, F.T.; Pan, X.Y.; Yang, Y.; Huang, C.; et al. Suppression of SUN2 by DNA methylation is associated with HSCs activation and hepatic fibrosis. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheen-Chen, S.M.; Lin, C.R.; Chen, K.H.; Yang, C.H.; Lee, C.T.; Huang, H.W.; Huang, C.Y. Epigenetic histone methylation regulates transforming growth factor beta-1 expression following bile duct ligation in rats. J. Gastroenterol 2014, 49, 1285–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugorria, M.J.; Wilson, C.L.; Zeybel, M.; Walsh, M.; Amin, S.; Robinson, S.; White, S.A.; Burt, A.D.; Oakley, F.; Tsukamoto, H.; et al. Histone methyltransferase ASH1 orchestrates fibrogenic gene transcription during myofibroblast transdifferentiation. Hepatology 2012, 56, 1129–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannaerts, I.; Eysackers, N.; Onyema, O.O.; Van Beneden, K.; Valente, S.; Mai, A.; Odenthal, M.; van Grunsven, L.A. Class II HDAC inhibition hampers hepatic stellate cell activation by induction of microRNA-29. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Van Beneden, K.; Mannaerts, I.; Pauwels, M.; Van den Branden, C.; van Grunsven, L.A. HDAC inhibitors in experimental liver and kidney fibrosis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair 2013, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bahat, A.; Gross, A. Mitochondrial plasticity in cell fate regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 13852–13863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yin, X.; Zheng, F.; Pan, Q.; Zhang, S.; Yu, D.; Xu, Z.; Li, H. Glucose fluctuation increased hepatocyte apoptosis under lipotoxicity and the involvement of mitochondrial permeability transition opening. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2015, 55, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mantena, S.K.; Vaughn, D.P.; Andringa, K.K.; Eccleston, H.B.; King, A.L.; Abrams, G.A.; Doeller, J.E.; Kraus, D.W.; Darley-Usmar, V.M.; Bailey, S.M. High fat diet induces dysregulation of hepatic oxygen gradients and mitochondrial function in vivo. Biochem. J. 2009, 417, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fan, W.X.; Wen, X.L.; Xiao, H.; Yang, Q.P.; Liang, Z. MicroRNA-29a enhances autophagy in podocytes as a protective mechanism against high glucose-induced apoptosis by targeting heme oxygenase-1. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharm. Sci. 2018, 22, 8909–8917. [Google Scholar]

- Vringer, E.; Tait, S.W.G. Mitochondria and Inflammation: Cell Death Heats Up. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Liang, S.; Sanchez-Lopez, E.; He, F.; Shalapour, S.; Lin, X.J.; Wong, J.; Ding, S.; Seki, E.; Schnabl, B.; et al. New mitochondrial DNA synthesis enables NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature 2018, 560, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhir, A.; Dhir, S.; Borowski, L.S.; Jimenez, L.; Teitell, M.; Rotig, A.; Crow, Y.J.; Rice, G.I.; Duffy, D.; Tamby, C.; et al. Mitochondrial double-stranded RNA triggers antiviral signalling in humans. Nature 2018, 560, 238–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, P.E.; Oliveira, A.G.; Pereira, R.V.; David, B.A.; Gomides, L.F.; Saraiva, A.M.; Pires, D.A.; Novaes, J.T.; Patricio, D.O.; Cisalpino, D.; et al. Hepatic DNA deposition drives drug-induced liver injury and inflammation in mice. Hepatology 2015, 61, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Martinez, I.; Santoro, N.; Chen, Y.; Hoque, R.; Ouyang, X.; Caprio, S.; Shlomchik, M.J.; Coffman, R.L.; Candia, A.; Mehal, W.Z. Hepatocyte mitochondrial DNA drives nonalcoholic steatohepatitis by activation of TLR9. J. Clin. Investig. 2016, 126, 859–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Murgia, M.; Giorgi, C.; Pinton, P.; Rizzuto, R. Controlling metabolism and cell death: At the heart of mitochondrial calcium signalling. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2009, 46, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Murphy, M.P. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem. J. 2009, 417, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chaung, W.W.; Wu, R.; Ji, Y.; Dong, W.; Wang, P. Mitochondrial transcription factor A is a proinflammatory mediator in hemorrhagic shock. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2012, 30, 199–203. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.H.; Shim, Y.R.; Seo, W.; Kim, M.H.; Choi, W.M.; Kim, H.H.; Kim, Y.E.; Yang, K.; Ryu, T.; Jeong, J.M.; et al. Mitochondrial double-stranded RNA in exosome promotes interleukin-17 production through toll-like receptor 3 in alcoholic liver injury. Hepatology 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, X.; Qu, J.H.; Liu, B.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, T.; Fan, P.C.; Wang, X.M.; Xiao, G.Y.; Su, Y.; et al. Caloric Restriction Induces MicroRNAs to Improve Mitochondrial Proteostasis. iScience 2019, 17, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ding, J.; Li, M.; Wan, X.; Jin, X.; Chen, S.; Yu, C.; Li, Y. Effect of miR-34a in regulating steatosis by targeting PPARalpha expression in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Sci Rep. 2015, 5, 13729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loyer, X.; Paradis, V.; Henique, C.; Vion, A.C.; Colnot, N.; Guerin, C.L.; Devue, C.; On, S.; Scetbun, J.; Romain, M.; et al. Liver microRNA-21 is overexpressed in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and contributes to the disease in experimental models by inhibiting PPARalpha expression. Gut. 2016, 65, 1882–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rector, R.S.; Thyfault, J.P.; Uptergrove, G.M.; Morris, E.M.; Naples, S.P.; Borengasser, S.J.; Mikus, C.R.; Laye, M.J.; Laughlin, M.H.; Booth, F.W.; et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction precedes insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis and contributes to the natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in an obese rodent model. J. Hepatol. 2010, 52, 727–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grattagliano, I.; de Bari, O.; Bernardo, T.C.; Oliveira, P.J.; Wang, D.Q.; Portincasa, P. Role of mitochondria in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease--from origin to propagation. Clin. Biochem. 2012, 45, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunny, N.E.; Bril, F.; Cusi, K. Mitochondrial Adaptation in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Novel Mechanisms and Treatment Strategies. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2017, 28, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Degli Esposti, D.; Hamelin, J.; Bosselut, N.; Saffroy, R.; Sebagh, M.; Pommier, A.; Martel, C.; Lemoine, A. Mitochondrial roles and cytoprotection in chronic liver injury. Biochem. Res. Int. 2012, 2012, 387626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, S.; Zhao, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, P.; Zhou, W.; Yang, P.; Varghese, Z.; Moorhead, J.F.; et al. Cluster of Differentiation 36 Deficiency Aggravates Macrophage Infiltration and Hepatic Inflammation by Upregulating Monocyte Chemotactic Protein-1 Expression of Hepatocytes Through Histone Deacetylase 2-Dependent Pathway. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2017, 27, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Febbraio, M.; Wada, T.; Zhai, Y.; Kuruba, R.; He, J.; Lee, J.H.; Khadem, S.; Ren, S.; Li, S.; et al. Hepatic fatty acid transporter Cd36 is a common target of LXR, PXR, and PPARgamma in promoting steatosis. Gastroenterology 2008, 134, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, Z.; Ren, H.; Peng, M.L. Role of CD36 in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi 2017, 25, 953–956. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Koch, M.; di Giuseppe, R.; Evans, K.; Borggrefe, J.; Nothlings, U.; Handberg, A.; Jensen, M.K.; Lieb, W. Associations of plasma CD36 and body fat distribution. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, Jc.2019-00368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, P.; Zhao, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zeng, S.; Wei, L.; Varghese, Z.; Moorhead, J.F.; Chen, Y.; et al. CD36 plays a negative role in the regulation of lipophagy in hepatocytes through an AMPK-dependent pathway. J. Lipid Res. 2019, 60, 844–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wilson, C.G.; Tran, J.L.; Erion, D.M.; Vera, N.B.; Febbraio, M.; Weiss, E.J. Hepatocyte-Specific Disruption of CD36 Attenuates Fatty Liver and Improves Insulin Sensitivity in HFD-Fed Mice. Endocrinology 2016, 157, 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Begriche, K.; Massart, J.; Robin, M.A.; Bonnet, F.; Fromenty, B. Mitochondrial adaptations and dysfunctions in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2013, 58, 1497–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, J.K.; Rao, M.S. Lipid metabolism and liver inflammation. II. Fatty liver disease and fatty acid oxidation. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006, 290, G852–G858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, M.; Huang, W.; Chen, W.; Zhao, Y.; Schulte, M.L.; Volberding, P.J.; Gerbec, Z.; Zimmermann, M.T.; Zeighami, A.; et al. Mitochondrial Metabolic Reprogramming by CD36 Signaling Drives Macrophage Inflammatory Responses. Circ. Res. 2019, 125, 1087–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ipsen, D.H.; Lykkesfeldt, J.; Tveden-Nyborg, P. Molecular mechanisms of hepatic lipid accumulation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 3313–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McGettigan, B.; McMahan, R.; Orlicky, D.; Burchill, M.; Danhorn, T.; Francis, P.; Cheng, L.L.; Golden-Mason, L.; Jakubzick, C.V.; Rosen, H.R. Dietary Lipids Differentially Shape Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Progression and the Transcriptome of Kupffer Cells and Infiltrating Macrophages. Hepatology 2019, 70, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, C.M.; Ho, S.L.; Jeng, Y.M.; Lai, Y.S.; Chen, Y.H.; Lu, S.C.; Chen, H.L.; Chang, P.Y.; Hu, R.H.; Lee, P.H. Accumulation of free cholesterol and oxidized low-density lipoprotein is associated with portal inflammation and fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Inflamm. (Lond) 2019, 16, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Houben, T.; Oligschlaeger, Y.; Bitorina, A.V.; Hendrikx, T.; Walenbergh, S.M.A.; Lenders, M.H.; Gijbels, M.J.J.; Verheyen, F.; Lutjohann, D.; Hofker, M.H.; et al. Blood-derived macrophages prone to accumulate lysosomal lipids trigger oxLDL-dependent murine hepatic inflammation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kawanishi, N.; Mizokami, T.; Yada, K.; Suzuki, K. Exercise training suppresses scavenger receptor CD36 expression in kupffer cells of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis model mice. Physiol. Rep. 2018, 6, e13902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, R.W.; Lian, W.S.; Chen, Y.S.; Kuo, C.W.; Ke, H.C.; Hsieh, C.K.; Wang, S.Y.; Ko, J.Y.; Wang, F.S. MicroRNA-29a Counteracts Glucocorticoid Induction of Bone Loss through Repressing TNFSF13b, Modulation of Osteoclastogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Merrill, R.A.; Strack, S. A-Kinase Anchoring Protein 1: Emerging Roles in Regulating Mitochondrial Form and Function in Health and Disease. Cells 2020, 9, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mansouri, A.; Gattolliat, C.H.; Asselah, T. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Signaling in Chronic Liver Diseases. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 629–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bargaje, R.; Gupta, S.; Sarkeshik, A.; Park, R.; Xu, T.; Sarkar, M.; Halimani, M.; Roy, S.S.; Yates, J.; Pillai, B. Identification of novel targets for miR-29a using miRNA proteomics. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, J.; Tong, Q.; Wang, G.; Dong, H.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Q.; Wu, H. Reduction of miR-29a-3p induced cardiac ischemia reperfusion injury in mice via targeting Bax. Exp. Med. 2019, 18, 1729–1737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betaneli, V.; Petrov, E.P.; Schwille, P. The role of lipids in VDAC oligomerization. Biophys. J. 2012, 102, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ouyang, Y.B.; Xu, L.; Lu, Y.; Sun, X.; Yue, S.; Xiong, X.X.; Giffard, R.G. Astrocyte-enriched miR-29a targets PUMA and reduces neuronal vulnerability to forebrain ischemia. Glia 2013, 61, 1784–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jan, M.I.; Khan, R.A.; Malik, A.; Ali, T.; Bilal, M.; Bo, L.; Sajid, A.; Urehman, N.; Waseem, N.; Nawab, J.; et al. Data of expression status of miR- 29a and its putative target mitochondrial apoptosis regulatory gene DRP1 upon miR-15a and miR-214 inhibition. Data Brief. 2018, 16, 1000–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simao, A.L.; Afonso, M.B.; Rodrigues, P.M.; Gama-Carvalho, M.; Machado, M.V.; Cortez-Pinto, H.; Rodrigues, C.M.P.; Castro, R.E. Skeletal muscle miR-34a/SIRT1:AMPK axis is activated in experimental and human non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Mol. Med. (Berl) 2019, 97, 1113–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Feng, L.; Zheng, Y.L.; Lu, J.; Fan, S.H.; Shan, Q.; Zheng, G.H.; Wang, Y.J.; Wu, D.M.; Li, M.Q.; et al. 2, 2′, 4, 4′-tetrabromodiphenyl ether (BDE-47) induces mitochondrial dysfunction and related liver injury via eliciting miR-34a-5p-mediated mitophagy impairment. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 258, 113693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebeaupin, C.; Vallee, D.; Hazari, Y.; Hetz, C.; Chevet, E.; Bailly-Maitre, B. Endoplasmic reticulum stress signalling and the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 927–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, U.C.; Ramana, K.V. Regulation of NF-kappaB-induced inflammatory signaling by lipid peroxidation-derived aldehydes. Oxid Med. Cell Longev. 2013, 2013, 690545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, G.Y.; Rui, C.; Chen, J.Q.; Sho, E.; Zhan, S.S.; Yuan, X.W.; Ding, Y.T. MicroRNA-122 Inhibits Lipid Droplet Formation and Hepatic Triglyceride Accumulation via Yin Yang 1. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 44, 1651–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csak, T.; Bala, S.; Lippai, D.; Satishchandran, A.; Catalano, D.; Kodys, K.; Szabo, G. microRNA-122 regulates hypoxia-inducible factor-1 and vimentin in hepatocytes and correlates with fibrosis in diet-induced steatohepatitis. Liver Int. 2015, 35, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, Z.Y.; Xi, Y.; Zhu, W.N.; Zeng, C.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Guo, Z.C.; Hao, D.L.; Liu, G.; Feng, L.; Chen, H.Z.; et al. Positive regulation of hepatic miR-122 expression by HNF4alpha. J. Hepatol. 2011, 55, 602–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiang, J.; Tao, Y.F.; Bao, J.W.; Chen, J.; Li, H.X.; He, J.; Xu, P. High Fat Diet-Induced miR-122 Regulates Lipid Metabolism and Fat Deposition in Genetically Improved Farmed Tilapia (GIFT, Oreochromis niloticus) Liver. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rodrigues, P.M.; Rodrigues, C.M.P.; Castro, R.E. Modulation of liver steatosis by miR-21/PPARalpha. Cell Death Discov. 2018, 4, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calo, N.; Ramadori, P.; Sobolewski, C.; Romero, Y.; Maeder, C.; Fournier, M.; Rantakari, P.; Zhang, F.P.; Poutanen, M.; Dufour, J.F.; et al. Stress-activated miR-21/miR-21* in hepatocytes promotes lipid and glucose metabolic disorders associated with high-fat diet consumption. Gut 2016, 65, 1871–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ni, K.; Wang, D.; Xu, H.; Mei, F.; Wu, C.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, B. miR-21 promotes non-small cell lung cancer cells growth by regulating fatty acid metabolism. Cancer Cell Int. 2019, 19, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Davalos, A.; Goedeke, L.; Smibert, P.; Ramirez, C.M.; Warrier, N.P.; Andreo, U.; Cirera-Salinas, D.; Rayner, K.; Suresh, U.; Pastor-Pareja, J.C.; et al. miR-33a/b contribute to the regulation of fatty acid metabolism and insulin signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 9232–9237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rayner, K.J.; Suarez, Y.; Davalos, A.; Parathath, S.; Fitzgerald, M.L.; Tamehiro, N.; Fisher, E.A.; Moore, K.J.; Fernandez-Hernando, C. MiR-33 contributes to the regulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Science 2010, 328, 1570–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horie, T.; Nishino, T.; Baba, O.; Kuwabara, Y.; Nakao, T.; Nishiga, M.; Usami, S.; Izuhara, M.; Sowa, N.; Yahagi, N.; et al. MicroRNA-33 regulates sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 expression in mice. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Price, N.L.; Rotllan, N.; Canfran-Duque, A.; Zhang, X.; Pati, P.; Arias, N.; Moen, J.; Mayr, M.; Ford, D.A.; Baldan, A.; et al. Genetic Dissection of the Impact of miR-33a and miR-33b during the Progression of Atherosclerosis. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 1317–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karunakaran, D.; Richards, L.; Geoffrion, M.; Barrette, D.; Gotfrit, R.J.; Harper, M.E.; Rayner, K.J. Therapeutic Inhibition of miR-33 Promotes Fatty Acid Oxidation but Does Not Ameliorate Metabolic Dysfunction in Diet-Induced Obesity. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2015, 35, 2536–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mattis, A.N.; Song, G.; Hitchner, K.; Kim, R.Y.; Lee, A.Y.; Sharma, A.D.; Malato, Y.; McManus, M.T.; Esau, C.C.; Koller, E.; et al. A screen in mice uncovers repression of lipoprotein lipase by microRNA-29a as a mechanism for lipid distribution away from the liver. Hepatology 2015, 61, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- da Silva Meirelles, L.; Marson, R.F.; Solari, M.I.G.; Nardi, N.B. Are Liver Pericytes Just Precursors of Myofibroblasts in Hepatic Diseases? Insights from the Crosstalk between Perivascular and Inflammatory Cells in Liver Injury and Repair. Cells 2020, 9, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tsuchida, T.; Friedman, S.L. Mechanisms of hepatic stellate cell activation. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017, 14, 397–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomita, K.; Teratani, T.; Suzuki, T.; Shimizu, M.; Sato, H.; Narimatsu, K.; Okada, Y.; Kurihara, C.; Irie, R.; Yokoyama, H.; et al. Free cholesterol accumulation in hepatic stellate cells: Mechanism of liver fibrosis aggravation in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Hepatology 2014, 59, 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshida, K.; Murata, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Matsuzaki, K. TGF-beta/Smad signaling during hepatic fibro-carcinogenesis (review). Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 45, 1363–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ding, N.; Hah, N.; Yu, R.T.; Sherman, M.H.; Benner, C.; Leblanc, M.; He, M.; Liddle, C.; Downes, M.; Evans, R.M. BRD4 is a novel therapeutic target for liver fibrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 15713–15718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Knabel, M.K.; Ramachandran, K.; Karhadkar, S.; Hwang, H.W.; Creamer, T.J.; Chivukula, R.R.; Sheikh, F.; Clark, K.R.; Torbenson, M.; Montgomery, R.A.; et al. Systemic Delivery of scAAV8-Encoded MiR-29a Ameliorates Hepatic Fibrosis in Carbon Tetrachloride-Treated Mice. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, S.; Wu, Y.; Wang, J.; Yu, W.; Liu, Y. 1-deficient mice are resistant to thioacetamide-induced hepatic fibrosis: PU.1 finely regulates Sirt1 expression via transcriptional promotion of miR-34a and miR-29c in hepatic stellate cells. Biosci. Rep. 2017, 37, BSR20170926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feili, X.; Wu, S.; Ye, W.; Tu, J.; Lou, L. MicroRNA-34a-5p inhibits liver fibrosis by regulating TGF-beta1/Smad3 pathway in hepatic stellate cells. Cell Biol. Int. 2018, 42, 1370–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, X.; Cheng, F.; Ji, L.; Zhu, X.; Cao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, X.; Zhou, Q.; Guan, W.; Zhou, Y. Leptin reduces microRNA-122 level in hepatic stellate cells in vitro and in vivo. Mol. Immunol. 2017, 92, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Affected Pathway | Disease Model | miR-29a Targets | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epigenetics | NASH, liver fibrosis, HCC | DNMT3b, HDAC4, DNMT3a, TET1 | [37,38,39,40,41,42,43] |

| Oxidative stress/Inflammatory | NASH, liver fibrosis, HCC | CD36, DNMT3b, HDAC4, ARRB1, PTEN | [37,40,44,45,46,47,48,49] |

| Apoptosis | liver fibrosis, HCC | COL1A1, FGL2, MAP4K4, PDGFC, BCL-2, DNMT3a, MCL-1 | [42,46,48,50,51,52] |

| Autophagy | NASH, liver fibrosis, HCC | DNMT3b, SPARC | [36,37,51] |

| Epithelial-mesenchymal transition | NASH, liver fibrosis | COL1A1, FGL2, MAP4K4, PDGFC | [37,39,40,44,45,46,48,51,53] |

| Cell cycle | HCC | SIRT1; SPARC; HULC, TET1, TET2, TET3 | [36,41,43,54,55] |

| Cell migration | HCC | CLDN1, TET1, TET2, TET3, PTEN | [41,43,56] |

| Source | Expression | Clinical Relevance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma | Down | Biomarker implicated in miRFIB scoring algorithm for diagnosis of liver fibrosis | [31] |

| Serum | Down | Reduced miR-29a along with elevated miR-122 serve as a diagnostic panel for NAFLD | [29] |

| Serum | Down | negatively correlated with necroinflammation and liver fibrosis | [30] |

| Serum | Down | Biomarker of advanced liver cirrhosis | [32] |

| Serum | Up | Biomarker of HCC | [67] |

| Plasma | Down | Prognostic marker of poor outcome of HCC | [33] |

| Serum | Up | Predictor for poor survival of HCC | [70] |

| HCC tissue | Up | Predictor for recurrence of HCC | [35] |

| HCC tissue | Down | Prognostic marker of poor outcome of HCC | [55] |

| HCC tissue | Down | Predictor for low survival rate of HCC | [36] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, H.-Y.; Yang, Y.-L.; Wang, P.-W.; Wang, F.-S.; Huang, Y.-H. The Emerging Role of MicroRNAs in NAFLD: Highlight of MicroRNA-29a in Modulating Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Beyond. Cells 2020, 9, 1041. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9041041

Lin H-Y, Yang Y-L, Wang P-W, Wang F-S, Huang Y-H. The Emerging Role of MicroRNAs in NAFLD: Highlight of MicroRNA-29a in Modulating Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Beyond. Cells. 2020; 9(4):1041. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9041041

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Hung-Yu, Ya-Ling Yang, Pei-Wen Wang, Feng-Sheng Wang, and Ying-Hsien Huang. 2020. "The Emerging Role of MicroRNAs in NAFLD: Highlight of MicroRNA-29a in Modulating Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Beyond" Cells 9, no. 4: 1041. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9041041

APA StyleLin, H.-Y., Yang, Y.-L., Wang, P.-W., Wang, F.-S., & Huang, Y.-H. (2020). The Emerging Role of MicroRNAs in NAFLD: Highlight of MicroRNA-29a in Modulating Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Beyond. Cells, 9(4), 1041. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9041041