Expanding the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Reveal Urban Residents’ Pro-Environment Travel Behaviour

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Expansion and Application of the Theory of Planned Behaviour

1.2. Adopting Qualitative Research for PT Service Quality Measurement

1.3. Choice of Data Analysis Method

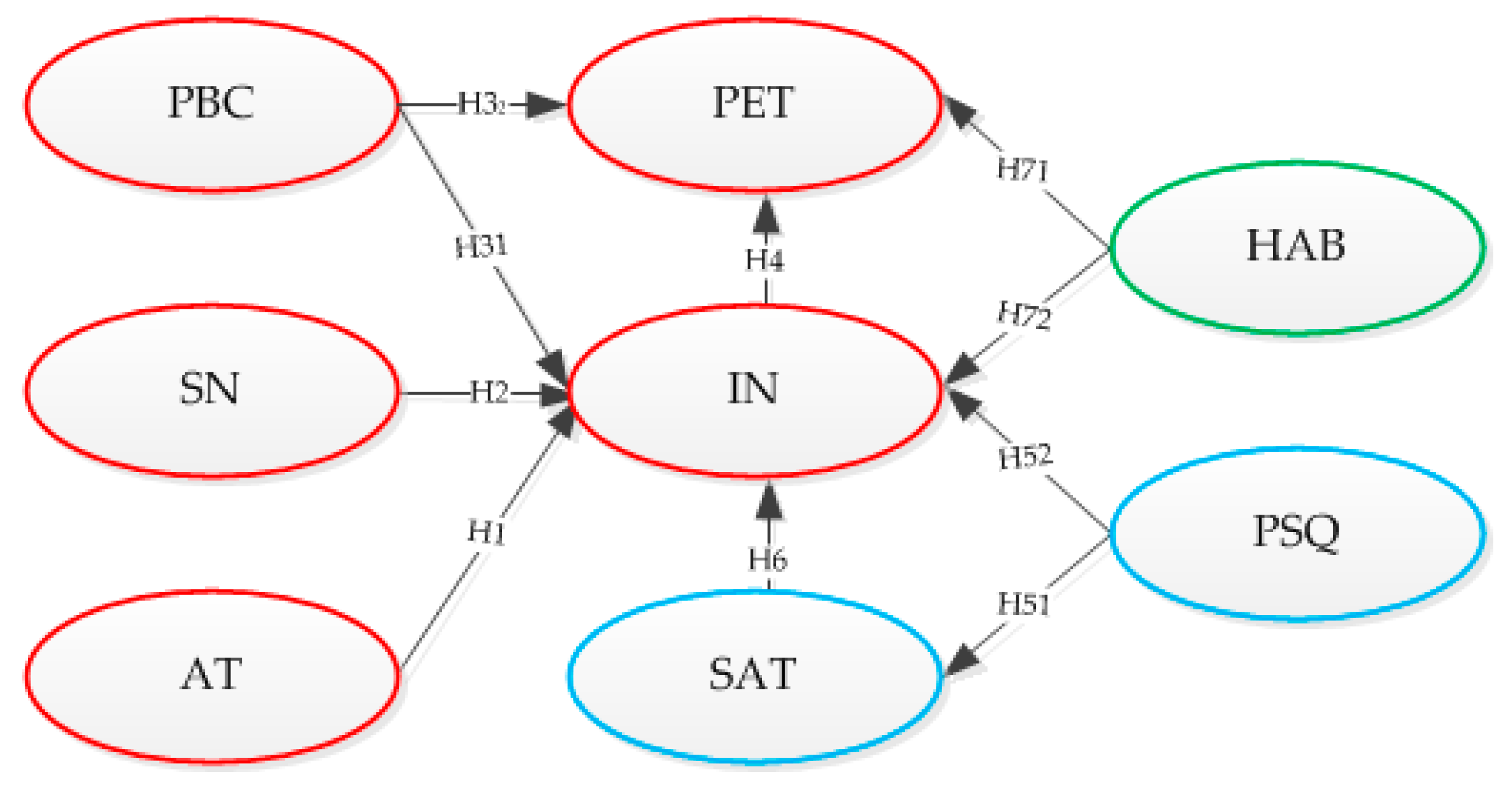

2. Conceptual Model and Hypotheses

2.1. TPB

2.2. Satisfaction Theory

2.3. Habit

3. Methodology

3.1. Qualitative Research

3.2. Coding Analysis

3.3. Consistency Checking of Coding Results

3.4. Questionnaire

3.5. Tests of the Quantitative Table

3.5.1. Sample Description

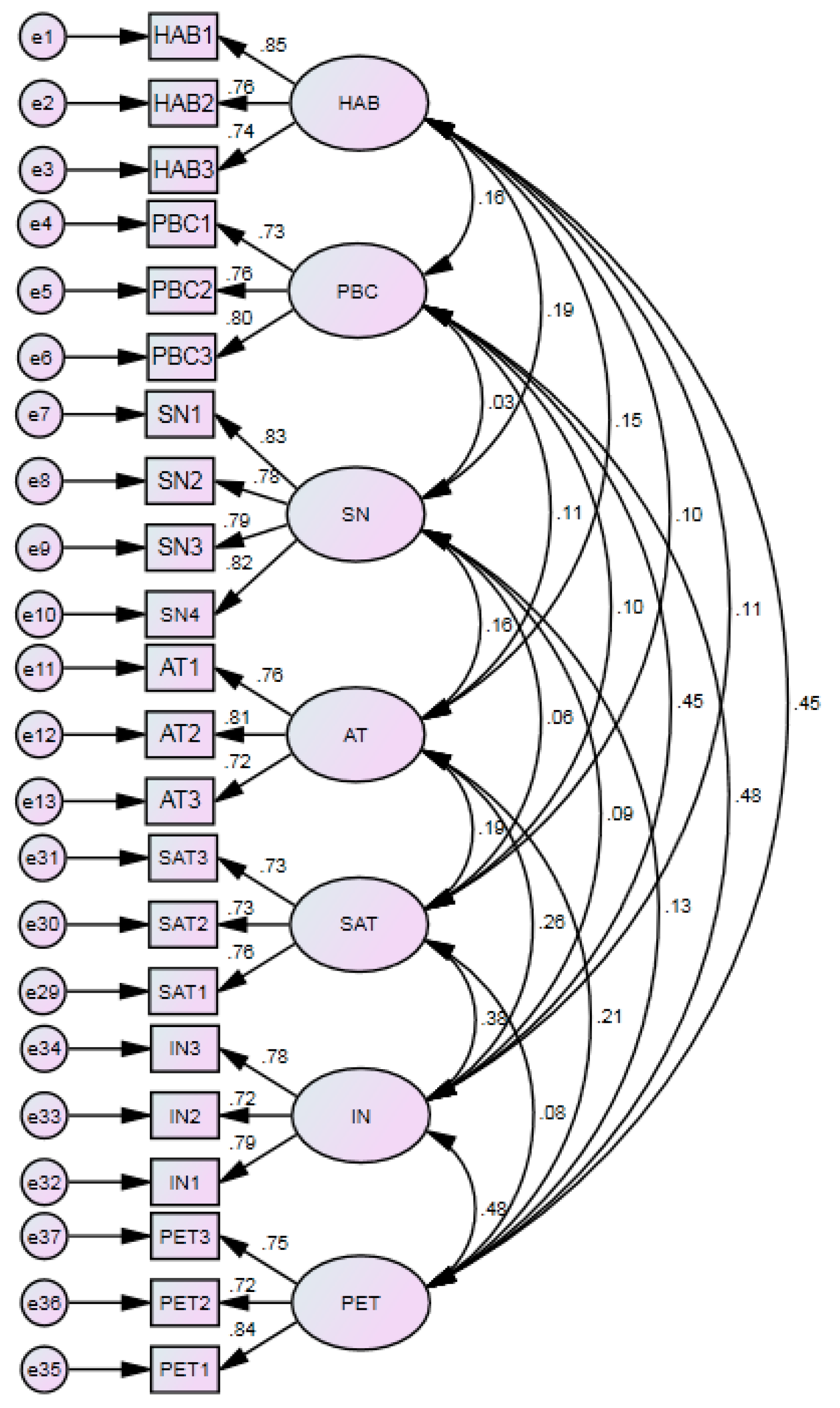

3.5.2. Tests of Reliability and Validity

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Fitting Test of Structural Equation Model

4.2. Analysis of the Factors of Pro-Environment Travel Behaviour

4.2.1. Path Analysis

4.2.2. Analysis of the Effects of TPB Variables

4.2.3. Analysis of the Effects of Perceived PT Service Quality and Satisfaction

4.2.4. Analysis of the Effects of Habit Variables

4.3. Analysis of the Effects of Social Economy Attributes on Latent Variables

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| First-class Categories | Second-class Categories | Third-class Categories | Number of interviews (N = 24) | Frequency | Coding Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSQ | Vehicle environment (VE) | Density of passengers | 20 | 33 | Crowded while standing, extremely difficult to move; vehicle is packed with passengers |

| Hygiene and safety environment | 17 | 29 | It’s too hot in the car; too messy to bear | ||

| Integrity of facilities | 9 | 17 | Seats; arrival broadcasts; safety hammers; monitors | ||

| Transportation network (TN) | Convenience of transfer | 7 | 9 | Inconvenient transfers; several transfers are required | |

| Platform coverage | 10 | 21 | More than a 10-minute walk to the station | ||

| Through route | 11 | 20 | A through transit route is unavailable; the No. 202 bus takes a long detour | ||

| Efficiency of bus transit | 13 | 21 | Buses run too slowly; commuting by bus causes passengers to be late for work | ||

| Operation and management (OM) | Frequency | 14 | 21 | Frequency is too low; passengers have to wait for too long | |

| Punctuality | 10 | 20 | Arriving at stops on time and without delays on live schedules | ||

| Service time | 6 | 7 | Service stops by 6 or 7 pm; the length of the service period is too short | ||

| Drivers’ professional skills | 19 | 32 | Drivers frequently brake sharply; obey rules on stopping at certain places; easily lose their temper | ||

| Fares | 12 | 19 | Fares are cheap; transit fares are reasonable | ||

| Information and technology (IT) | Top-up methods | 4 | 7 | Top-up for IC cards is available on the Internet | |

| Modes of payment | 6 | 14 | Payment by smartphone; multiple-day travel pass is available | ||

| Wi-Fi coverage | 10 | 19 | Wi-Fi is available on transit; Wi-Fi is the most crucial issue | ||

| Real-time traffic information | 5 | 11 | Digital boards show estimated arrival times with route numbers |

| Latent Variables and Observation Variables | Definitions and Observed Items |

|---|---|

| SN: These comprise a descriptive norm or prohibition. The specific meaning is an individual’s perception of social pressure and the extent to which he/she has been influenced by others when deciding whether or not to engage in a particular pro-environment travel behaviour. | |

| SN1 | My family or close friends support me in pro-environment travel. |

| SN2 | Government policies have an important effect on my decision. |

| SN3 | My family or close friends use pro-environment modes of travel. |

| SN4 | The social vibe encourages me to use PT. |

| PBC: Including self-efficacy and self-control, this refers to the extent to which individuals perceive pro-environment travel behaviours to be easy or difficult, and how much these are limited by their resources and opportunities (e.g., travel information, time and money). This variable reflects an individual’s ability to control objective situations. | |

| PBC1: | Individuals choose pro-environment travel, and this entirely depends on their perception. |

| PBC2: | Pro-environment travel is readily accessible to me. |

| PBC3: | I have the confidence to use only pro-environment modes of travel in the next few weeks. |

| AT: This refers to individuals’ positive or negative evaluation of pro-environment travel behaviour, reflecting the extent to which they like or dislike it (i.e., whether they feel happy or sad, or evaluate it as beneficial or harmful, useless or useful). | |

| AT1: | I love taking PT. |

| AT2: | Using pro-environment modes of travel has benefits. |

| AT3: | I am delighted with my journey on PT. |

| IN: Defined as the subjective probability of an individual’s behaviour, this reflects his/her willingness to use a pro-environment mode of travel and the possibility of using it continuously and recommending it to others. | |

| IN1: | I am willing to use PT the next time I travel. |

| IN2: | I am willing to recommend PT to others. |

| IN3: | I intend to take PT rather than drive in the future. |

| SAT: Satisfaction is described as an emotional assessment of the extent to which positive emotions are experienced when using PT (i.e., the level of satisfaction), which depends on the extent to which the expected service is realised. | |

| SAT1: | I am satisfied with taking PT. |

| SAT2: | The use of pro-environment modes of travel is a brilliant choice. |

| SAT3: | I am barely satisfied with the PT service offered. |

| HAB: Habit is defined as behaviour without careful thought, which refers to not only the experience and frequency of using PT but also the extent to which difficulty is experienced in abandoning the use of pro-environment modes of travel. | |

| HAB1: | Taking PT has become part of my life. |

| HAB2: | It is hard to give up taking PT. |

| HAB3: | I often spontaneously take PT. |

| PET: This variable is defined as taking place in a specific environment at a specific time with a specific purpose. In this paper, it refers to taking pro-environment modes of transport instead of driving. | |

| PET1: | In general, I take PT. |

| PET2: | I have often taken PT within the last month. |

| PET3: | I have taken pro-environment modes of transport more frequently than driving within the last month. |

| VE: This defines passengers’ perception of the comfort, safety and availability of the facilities in transit (e.g., density of passengers, health and safety, handrails or rings, voice broadcasts and completeness of safety hammer). | |

| VE1: | The PT vehicle is spacious, not crowded with passengers and everyone obeys the rules. |

| VE2: | The PT vehicle is tidy and comfortable. |

| VE3: | A complete safety set is always available. |

| TN: This defines passengers’ perception of the convenience and speed of the layout of the transport network. More specifically, it includes the convenience of transfers, station coverage, through transit and the operating efficiency of vehicles. | |

| TN1: | Few transfers are needed, and transfers are convenient. |

| TN2: | Taking PT is convenient due to the high rate of coverage of stations. |

| TN3: | The designs of routes are reasonable, and detours are rare. |

| TN4: | Vehicles are efficient and fast. |

| OM: This is defined as passengers’ perception of reliability and economy. More specifically, it refers to frequency, punctuality, service time, professional skills of drivers, fares, etc. | |

| OM1: | Headway and waiting times are short. |

| OM2: | Vehicles always arrive at stops punctually. |

| OM3: | The schedule is reasonable and meets passengers’ demands. |

| OM4: | Drivers are patient, skilful and professional (e.g., drive smoothly). |

| OM5: | Fares are cheap and discounts are offered (i.e., they impose little burden). |

| IT: This refers to PT passengers’ perception of information technology service. Online recharge of IC cards, payment methods, Wi-Fi network coverage and real-time traffic information can be provided. | |

| IT1: | Online top-up of IC cards is available to passengers. |

| IT2: | Payments are user-friendly and online payments are available. |

| IT3: | Wi-Fi is accessible in nearly every vehicle. |

| IT4: | Real-time digital information boards are provided on platforms, and these are reliable. |

| Features | Participants | Features | Participants | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Proportion (%) | Population | Proportion (%) | ||||

| Gender | Male | 370 | 42.53 | Number of private vehicles | 0 | 360 | 41.38 |

| Female | 500 | 57.47 | 1 | 434 | 49.89 | ||

| Age | Under 18 | 12 | 1.38 | 2 | 57 | 6.55 | |

| 18–30 | 324 | 37.24 | >2 | 19 | 2.18 | ||

| 31–50 | 418 | 48.05 | Job | Student | 191 | 21.95 | |

| 51–60 | 112 | 12.87 | White collar/institution staff | 362 | 41.61 | ||

| Over 60 | 4 | 0.46 | Government official | 57 | 6.55 | ||

| Monthly income (RMB) | Under 2000 | 232 | 26.67 | Dealer | 61 | 7.01 | |

| 2000–4000 | 241 | 27.7 | Worker/steward | 56 | 6.44 | ||

| 4001–7000 | 232 | 26.67 | Retired | 21 | 2.41 | ||

| 7001–10,000 | 89 | 10.23 | Other | 122 | 14.02 | ||

| Over 10,000 | 76 | 8.74 | Driving years | No driver license | 293 | 33.68 | |

| Educational background | Below secondary school | 79 | 9.08 | Within a year | 125 | 14.37 | |

| Senior high school and secondary technical school | 129 | 14.83 | 1–5 years | 190 | 21.84 | ||

| Junior college and undergraduate | 492 | 56.55 | 5–10 years | 151 | 17.36 | ||

| Graduate and doctor | 170 | 19.54 | >10 years | 111 | 12.76 | ||

| Factor1 | Factor2 | Factor3 | Factor4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VE1 | 0.287 | 0.203 | 0.783 | 0.169 |

| VE2 | 0.220 | 0.238 | 0.759 | 0.205 |

| VE3 | 0.202 | 0.152 | 0.782 | 0.198 |

| TN1 | 0.208 | 0.148 | 0.271 | 0.722 |

| TN2 | 0.152 | 0.194 | 0.144 | 0.795 |

| TN3 | 0.216 | 0.143 | 0.138 | 0.805 |

| OM1 | 0.748 | 0.209 | 0.257 | 0.140 |

| OM2 | 0.735 | 0.164 | 0.202 | 0.135 |

| OM3 | 0.757 | 0.140 | 0.239 | 0.145 |

| OM4 | 0.770 | 0.174 | 0.095 | 0.211 |

| OM5 | 0.752 | 0.216 | 0.118 | 0.149 |

| IT1 | 0.227 | 0.766 | 0.167 | 0.167 |

| IT2 | 0.192 | 0.774 | 0.115 | 0.150 |

| IT3 | 0.165 | 0.799 | 0.138 | 0.137 |

| IT4 | 0.172 | 0.756 | 0.204 | 0.105 |

| Initial eigenvalue | 6.475 | 1.500 | 1.315 | 1.053 |

| Interpretation variance (%) | 21.742 | 18.424 | 14.672 | 14.118 |

References

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.T.; Chen, C.F. Behavioral intentions of public transit passengers—The roles of service quality, perceived value, satisfaction and involvement. Transp. Policy 2011, 18, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.P.; Xu, Y.J.; Chen, W.Y. Understanding attitudes towards pro-environmental travel: An empirical study from Tangshan city in China. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2014, 10, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.; Juan, Z. Understanding public transit use behavior: Integration of the theory of planned behavior and the customer satisfaction theory. Transportation 2017, 44, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, L.; Friman, M.; Garling, T.; Hartig, T. Quality attributes of public transport that attract car users: A research review. Transp. Policy 2013, 25, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, A.T. Strategic analysis of public transport coverage. Socio Econ. Plan. Sci. 2001, 35, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, I.J.; Cooper, S.R.; Conchie, S.M. An extended theory of planned behaviour model of the psychological factors affecting commuters’ transport mode use. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 40, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.O.; Walker, I.; Musselwhite, C. Grounded theory analysis of commuters discussing a workplace carbon-reduction target: Autonomy, satisfaction, and willingness to change behaviour in drivers, pedestrians, bicyclists, motorcyclists, and bus users. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2014, 26, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xingjun, R.; Shanyong, W.; Qian, C.; Shuai, Y. Exploring the interaction effects of norms and attitudes on green travel intention: An empirical study in eastern China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 1317–1327. [Google Scholar]

- Bamberg, S.; Hunecke, M.; Blobaum, A. Social context, personal norms and the use of public transportation: Two field studies. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, A.S.; Jayaraman, K.; Soh, K.-L.; Wong, W.P. Convenience, flexible service, and commute impedance as the predictors of drivers’ intention to switch and behavioral readiness to use public transport. Transp. Res. Part. F Psychol. Behav. 2019, 62, 505–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. Contributions of psychology to limiting climate change. Am. Psychol. 2011, 66, 127–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanzini, P.; Khan, S.A. Shedding light on the psychological and behavioral determinants of travel mode choice: A meta-analysis. Transp. Res. Part F Psychol. Behav. 2017, 48, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Chao, W.H. Habitual or reasoned? Using the theory of planned behavior, technology acceptance model, and habit to examine switching intentions toward public transit. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2011, 14, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, P.; Wang, J.; Chen, L.; Zha, Q. Incorporating the extended theory of planned behavior in a school travel mode choice model: A case study of Shaoxing, China. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2017, 41, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenting, D.; Guangrong, J. A Review of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Adv. Psychol. Sci. 2008, 2, 315–320. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, S.H.; van Breukelen, G.J.P.; Peters, G.-J.Y.; Kok, G. Proenvironmental travel behavior among office workers: A qualitative study of individual and organizational determinants. Transp. Res. Part A 2013, 56, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, Y.; Gifford, R. Extending the theory of planned behavior: Predicting the use of public transportation 1. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 32, 2154–2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, L.; Forward, S.E. Is the intention to travel in a pro-environmental manner and the intention to use the car determined by different factors? Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2011, 16, 372–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G. A moral extension of the theory of planned behavior: Norms and anticipated feelings of regret in conservationism. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2006, 41, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forward, S.E. The theory of planned behaviour: The role of descriptive norms and past behaviour in the prediction of drivers’ intentions to violate. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, S.; Kitamura, R. What does a one-month free bus ticket do to habitual drivers? An experimental analysis of habit and attitude change. Transportation 2003, 30, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prioni, P.; Hensher, D.A. Measuring service quality in scheduled bus services. J. Public Transp. 2000, 3, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beirão, G.; Sarsfield Cabral, J.A. Understanding attitudes towards public transport and private car: A qualitative study. Transp. Policy 2007, 14, 0–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensher, D.A.; Stopher, P.; Bullock, P. Service quality––Developing a service quality index in the provision of commercial bus contracts. Transp. Res. Part A 2003, 37, 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwanen, T.; Banister, D.; Anable, J. Scientific research about climate change mitigation in transport: A critical review. Transp. Res. Part A 2011, 45, 993–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mars, L.; Arroyo, R.; Ruiz, T. Qualitative research in travel behavior studies. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 18, 434–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L.; Strutzel, E. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Nurs. Res. 1968, 17, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Akiva, M.; De Palma, A.; Kanaroglou, P. Dynamic model of peak period traffic congestion with elastic arrival rates. Transp. Sci. 1986, 20, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, T.; Li, X.; Sun, Z. Effects of cost adjustment on travel mode choice: Analysis and comparison of different logit models. Transp. Res. Procedia 2017, 25, 2653–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salon, D. Neighborhoods, cars, and commuting in New York City: A discrete choice approach. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2009, 43, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yun, M.P.; Liu, G.Y.; Liu, F. Influence of change of public transportation service quality on travel mode choice behavior. China J. Highw. Transp. 2017, 30, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, K.M.N.; Kattan, L.; Islam, M.T. Model of personal attitudes towards transit service quality. J. Adv. Transp. 2011, 45, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yáñez, M.F.; Raveau, S.; de Ortúzar, J.D. Inclusion of latent variables in mixed logit models: Modelling and forecasting. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2010, 44, 744–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espino, R.; Román, C.; De Ortúzar, J.D. Analysing demand for suburban trips: A mixed RP/SP model with latent variables and interaction effects. Transportation 2006, 33, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulssen, M.; Temme, D.; Vij, A.; Walker, J. Values, attitudes and travel behavior: A hierarchical latent variable mixed logit model of travel mode choice. Transportation 2014, 41, 873–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, B.; Abraham, C. Psychological correlates of car use: A meta-analysis. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2008, 11, 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, A. The Potential Impact of New Urban Public Transport Systems on Travel Behaviour. Ph.D. Thesis, University of London, London, UK, 2001; pp. 277–287. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, S.H.; Breukelen, G.J.P.V.; Peters, G.J.Y.; Kok, G. Commuting travel mode choice among office workers: Comparing an extended theory of planned behavior model between regions and organizational sectors. Travel Behav. Soc. 2016, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Du, H.; Southworth, F.; Ma, S. The influence of social-psychological factors on the intention to choose low-carbon travel modes in Tianjin, China. Transp. Res. Part A 2017, 105, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeuw, A.D.; Valois, P.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Using the theory of planned behavior to identify key beliefs underlying pro-environmental behavior in high-school students: Implications for educational interventions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vos, J. Satisfaction-induced travel behaviour. Transp. Res. Part F Psychol. Behav. 2019, 63, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.K. The structural interrelationships of group service quality, customer satisfaction and behavioral intention for bus passengers. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2016, 10, 150106050212006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Oña, R.; Machado, J.L.; de Oña, J. Perceived service quality, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intentions: Structural equation model for the Metro of Seville, Spain. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2015, 1, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronin, J.J.; Brady, M.K.; Hult, G.T.M. Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. J. Retail. 2000, 76, 193–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TRB (Transportation Research Board). A Handbook for Measuring Customer Satisfaction and Service Quality; Transit Cooperative Research Program, Report 47; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Schwanen, T.; Banister, D.; Anable, J. Rethinking habit and their role in behaviour change: The case of low-carbon mobility. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 24, 522–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Choice of travel mode in the theory of planned behavior: The Roles of past behavior, habit, and reasoned action. Basic Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 25, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, B. Modelling motivation and habit in stable travel mode contexts. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verplanken, B.; Aarts, H.; Knippenberg, A.V.V.; Moonen, A. Habit versus planned behavior: A field experiment. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 37, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Ceder, A. Users’willingness to ride an integrated public-transport service: A literature review. Transp. Policy 2016, 48, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hine, J.; Scott, J. Seamless, accessible travel: users’ views of the public transport journey and interchange. Transp. Policy 2000, 7, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, M.L. Depth Interviews and Focus Groups. Formative Research in Social Marketing; Springer Publications: Singapore, 2017; pp. 67–87. [Google Scholar]

- Huberman, A.M.; Miles, M.B. Qualitative Data Analysis: An. Expanded Sourcebook; Sage Publications Inc.: London, UK; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; pp. 105–138. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Constructing a Theory of Planned Behavior Questionnaire. Available online: http://people.umass.edu/aizen/pdf/tpb.measurement.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2013).

- Yu, K.T.; Lee, N.H.; Wu, G.S. An empirical research of Kinmen tourists’ behavioral tendencies model—A case of cross-validation in causal modeling. J. Tour. Stud. 2005, 11, 355–384. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, C.Y. Applying the theory of planned behavior to explore the independent travelers’ behavior. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 4, 221–234. [Google Scholar]

- Garling, T.; Axhausen, K.W. Introduction: Habitual travel choice. Transportation 2003, 30, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golob, T.F. Structural equation modeling for travel behavior research. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2003, 37, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Armitage, C.J.; Conner, M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 471–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresnahan, M.; Young, L.S.; Smith, S.W.; Shearman, S.; Nebashi, R.; Park, C.Y.; Yoo, J. A theory of planned behavior study of college students’ intention to register as organ donors in Japan, Korea, and the United States. Health Commun. 2007, 21, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Features | Population | Proportion (%) | Features | Population | Proportion (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 15 | 55 | Age | Under 25 | 9 | 33 |

| Female | 12 | 45 | 26–35 | 14 | 52 | ||

| Educational background | Junior colleges | 3 | 11 | Over 36 | 4 | 15 | |

| Job | Student | 8 | 30 | ||||

| Undergraduate | 18 | 67 | Government official | 7 | 26 | ||

| Graduate | 6 | 22 | Dealer | 3 | 11 | ||

| Interview type | Face-to-face | 19 | 70 | Staff | 6 | 22 | |

| Internet | 8 | 30 | Researcher | 3 | 11 | ||

| Factors | AT | SN | PBC | IN | SAT | HAB | PET | VE | TN | OM | IT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of observed variables | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| Cronbach α of observed variables | 0.81 | 0.87 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.79 | 0.86 | 0.84 |

| Cronbach α of all observed variables | 0.87 | ||||||||||

| Path | C.R. | p | Standardised Loading | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OM ← PSQ | 0.808 | 0.6092 | 0.8616 | ||

| TN ← PSQ | 9.895 | *** | 0.746 | ||

| VE ← PSQ | 11.042 | *** | 0.809 | ||

| IT ← PSQ | 10.554 | *** | 0.757 | ||

| IT3 ← IT | 0.782 | 0.5726 | 0.8427 | ||

| IT2 ← IT | 15.595 | *** | 0.76 | ||

| IT1 ← IT | 15.45 | *** | 0.753 | ||

| IT4 ← IT | 14.976 | *** | 0.731 | ||

| OM1 ← OM | 0.792 | 0.5391 | 0.8537 | ||

| OM2 ← OM | 15.732 | *** | 0.743 | ||

| OM3 ← OM | 15.541 | *** | 0.735 | ||

| OM4 ← OM | 14.702 | *** | 0.7 | ||

| OM5 ← OM | 14.635 | *** | 0.697 | ||

| VE1 ← VE | 0.808 | 0.6189 | 0.8296 | ||

| VE2 ← VE | 16.522 | *** | 0.798 | ||

| VE3 ← VE | 15.651 | *** | 0.753 | ||

| TN1 ← TN | 0.723 | 0.5752 | 0.8023 | ||

| TN2 ← TN | 13.929 | *** | 0.784 | ||

| TN3 ← TN | 13.75 | *** | 0.767 |

| Hypothesis | S.E. | C.R. | p | Normalisation Parameter | Test Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAT ← PSQ | 0.062 | 8.29 | <0.05 | 0.383 | Confirmed |

| IN ← HAB | 0.047 | 6.817 | <0.05 | 0.303 | Confirmed |

| IN ← PBC | 0.04 | 10.059 | <0.05 | 0.417 | Confirmed |

| IN ← SN | 0.032 | 0.422 | 0.673 | 0.015 | Unconfirmed |

| IN ← AT | 0.039 | 12.801 | <0.05 | 0.527 | Confirmed |

| IN ← PSQ | 0.055 | 7.922 | <0.05 | 0.368 | Confirmed |

| IN ← SAT | 0.043 | 6.891 | <0.05 | 0.307 | Confirmed |

| PET ← HAB | 0.044 | 7.385 | <0.05 | 0.354 | Confirmed |

| PET ← PBC | 0.049 | 6.797 | <0.05 | 0.289 | Confirmed |

| PET ← IN | 0.052 | 14.703 | <0.05 | 0.535 | Confirmed |

| Latent Variable | Target Behaviour | Direct Effects | Indirect Effects | Total Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBC | pro-environmental travel behaviour | 0.289 | 0.223 | 0.512 |

| AT | 0.00 | 0.281 | 0.281 | |

| SAT | 0.00 | 0.164 | 0.164 | |

| PSQ | 0.00 | 0.197 | 0.197 | |

| HAB | 0.354 | 0.162 | 0.516 | |

| IN | 0.535 | 0.00 | 0.535 |

| Latent Variable | Gender | Age | Educational Background | Job | Number of Private Cars | Driving Years | Income |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VE | −24.829 | 22.019*** | 2.031 | 9.929*** | 0.042*** | 0.443 | 0.629*** |

| TN | −18.086*** | 11.725*** | 0.475 | 4.331*** | 0.565 | 0.918*** | 1.947 |

| OM | −21.851*** | 8.535 | 0.833 | 9.359*** | 0.351*** | 0.519*** | 0.513 |

| IT | −21.143 | 14.625*** | 0.104 | 5.607 | 0.562 | 0.981 | 0.952*** |

| HAB | 0.969*** | 0.374 | 1.945 | 7.139 | 0.653*** | 0.787*** | 0.495*** |

| PBC | 1.971* | 1.158 | 0.200*** | 1.141 | 3.488* | 2.127** | 1.717*** |

| SN | 0.369 | 2.525* | 0.203 | 1.821 | 1.348 | 1.635 | 0.545 |

| AT | −1.058 | 0.712*** | 1.520** | 1.347 | 13.103*** | 1.169 | 1.017 |

| SAT | −6.652*** | 1.555 | 0.712 | 1.369 | 1.201 | 1.915*** | 1.127 |

| IN | 0.94 | 0.447 | 0.820 | 2.284* | 17.222*** | 1.125 | 0.722*** |

| PET behaviour | 0.123 | 0.446 | 0.111** | 2.869** | 4.409*** | 1.500*** | 1.267*** |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, W.; Cao, C.; Fang, X.; Kang, Z. Expanding the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Reveal Urban Residents’ Pro-Environment Travel Behaviour. Atmosphere 2019, 10, 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos10080467

Chen W, Cao C, Fang X, Kang Z. Expanding the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Reveal Urban Residents’ Pro-Environment Travel Behaviour. Atmosphere. 2019; 10(8):467. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos10080467

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Weiya, Chao Cao, Xiaoping Fang, and Zixuan Kang. 2019. "Expanding the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Reveal Urban Residents’ Pro-Environment Travel Behaviour" Atmosphere 10, no. 8: 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos10080467

APA StyleChen, W., Cao, C., Fang, X., & Kang, Z. (2019). Expanding the Theory of Planned Behaviour to Reveal Urban Residents’ Pro-Environment Travel Behaviour. Atmosphere, 10(8), 467. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos10080467