Climate Change and Health Impacts in Urban Areas: Towards Hybrid Evaluation Tools for New Governance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Increasing Urbanisation and Related Negative Impacts

3. Environmental Pollution and Climate Change: The Global Framework

3.1. Environmental Pollution and Climate Change: Documents in the European Framework

3.2. Environmental Pollution, Climate Change and Health Impacts

- Scale up efforts and mobilise action globally.

- Massively implement solutions to burn less in any form.

- Strengthen action to protect the most vulnerable populations, especially children.

- Greatly increase access to clean energy and technologies in Africa and other areas with populations in the greatest need.

- Support cities to improve urban air quality.

- Enhance education on air pollution as a key factor for improving health and quality of life, within a lifelong learning approach.

- Enhance joint action between the financial, health and environmental sectors, and other key sectors affecting air pollution to generate business plans and specific actions leading to improved air quality and the mitigation of climate change. This includes a redirection of investments and adequate implementation of fiscal instruments.

- Develop and implement occupational safety and health regulations and measures to protect workers from occupational exposure to air pollution outdoors and indoors.

- Continue the joint effort for harmonised air pollution monitoring.

- Strategically complete knowledge and share it efficiently to address health risks. The generation of evidence concerning costs to society and efficient and cost-saving solutions is needed.

- Build key partnerships, programmes and initiatives to reduce air pollution to healthy levels [22].

3.3. Climate Change and Health Impacts: Documents in the Italian Framework

4. The Circular Economy and Circular City Models

5. Implementation Tools for Circular Economy

5.1. Urban Planning to Conserve, Restore and Regenerate Natural Capital

5.2. Evaluation Tools for New Governance

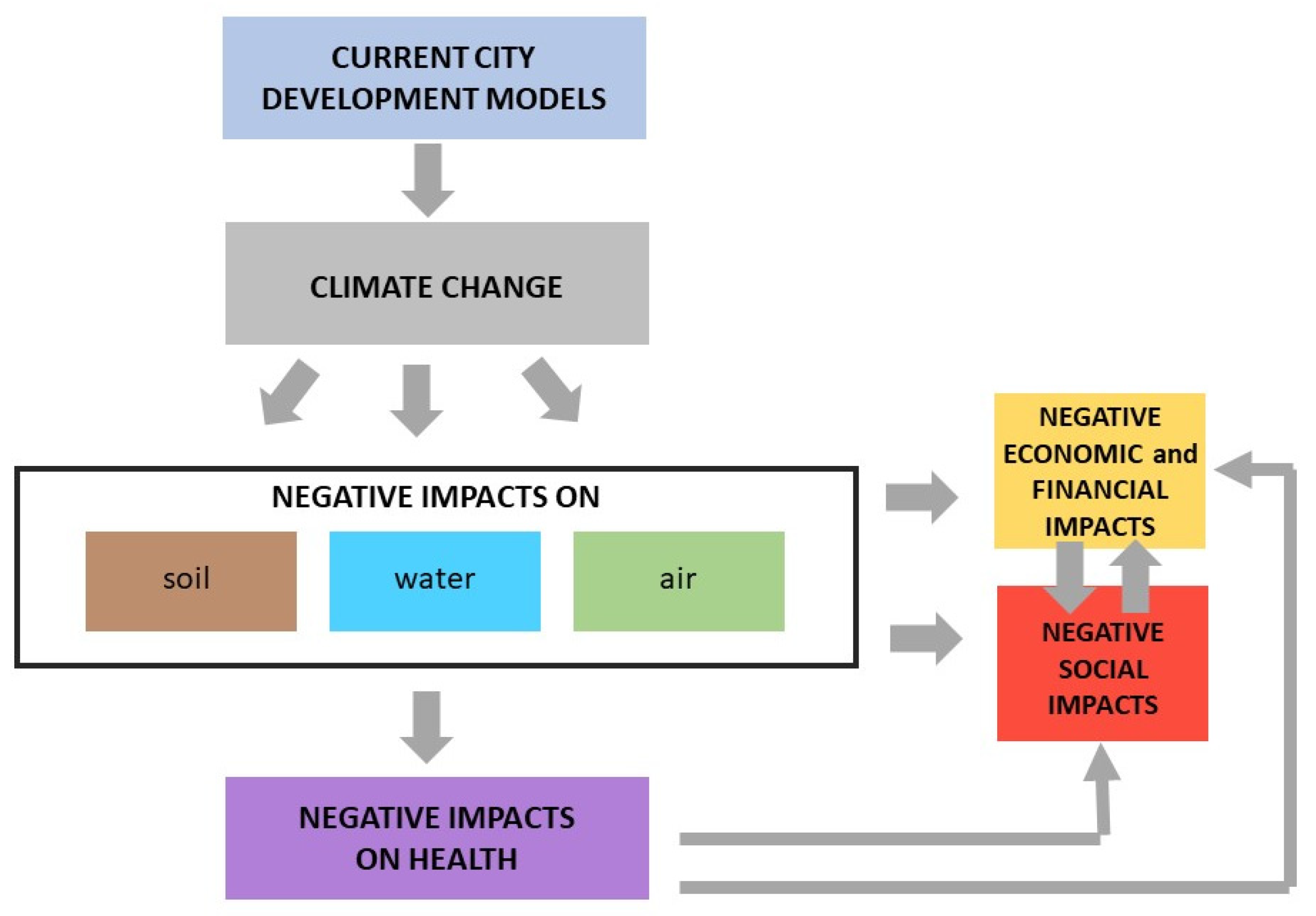

5.2.1. Multidimensional Impacts Due to Climate Change

5.2.2. Towards Hybrid Evaluation Tools for Assessing the Impacts of Urban Development on Health

6. Indicators for Assessing Health/Wellbeing Impacts of Urban Transformations

- Health;

- Education and training;

- Work and reconciliation of life time;

- Economic wellbeing;

- Social relations;

- Politics and institutions;

- Security;

- Subjective wellbeing;

- Landscape and cultural heritage;

- The environment;

- Innovation, research and creativity.

- The hope of life;

- The physical state index;

- The psychological status index;

- The infant mortality rate;

- The standardised cancer mortality rate;

- The unlimited life expectancy in daily activities at 65 years of age.

- The quality of marine coastal waters;

- Urban air quality;

- The availability of urban greenery;

- Contaminated sites;

- Areas of particular naturalistic interest;

- Preoccupation about the loss of biodiversity;

- Material flows (reference to the circular economy);

- CO2 emissions and other climate-altering gases.

- The employment rate (referring to the domain “work and reconciliation of life time”);

- The average available income per capita (referring to the domain “economic wellbeing”);

- Social participation (referring to the domain “social relations”);

- The presence of elements of degradation in the area where people live (referring to the domain “security”);

- Satisfaction of own life (referring to the subjective domain “wellbeing”);

- The density of historical greenery (referring to the domain “landscape and cultural heritage”);

- Innovation in the production system (referring to the domain “innovation, research and creativity”);

- Beds in residential social-health and social-health-care facilities (referring to the domain “quality of services”).

- Health and exposure to warming (with reference to the first domain related to the impacts of climate change on health);

- A change in labour capacity (with reference to the first domain related to the impacts of climate change on health);

- Global health trends in climate-sensitive diseases (with reference to the first domain related to the impacts of climate change on health);

- Food security and undernutrition (with reference to the first domain related to the impacts of climate change on health);

- National adaptation plans for health (with reference to the actions for reducing the above impacts);

- National assessments of climate change impacts, vulnerability and adaptation for health (with reference to the actions for reducing the above impacts);

- Adaptation delivery and implementation (with reference to the actions for reducing the above impacts);

- The detection of, preparedness for and response to health emergencies (with reference to the actions for reducing the above impacts);

- Spending on adaptation for health and health-related activities (with reference to the actions for reducing the above impacts);

- The carbon intensity of the energy system (with reference to the solutions able to mitigate the impacts);

- Exposure to air pollution in cities (with reference to the solutions able to mitigate the impacts);

- Premature mortality from ambient air pollution by sector (with reference to the solutions able to mitigate the impacts);

- Sustainable and healthy transport (with reference to the solutions able to mitigate the impacts);

- Mitigation in the health-care sector (with reference to the solutions able to mitigate the impacts);

- Economic losses due to climate-related extreme events (with reference to the costs concerning the damage caused);

- The economic costs of air pollution (with reference to the costs concerning the damage caused);

- Investing in a low-carbon economy (with reference to the costs concerning the solutions to be adopted);

- Investment in new coal capacity (with reference to the costs concerning the solutions to be adopted);

- Investments in low-carbon energy and energy efficiency (with reference to the costs concerning the solutions to be adopted);

- Individual engagement in health and climate change (with reference to the effectiveness of community participation);

- Engagement in health and climate change in the UN (with reference to the effectiveness of public participation).

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations, Draft Outcome Document of the United Nations Conference on Housing and Sustainable Urban Development (Habitat III); United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2016.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the World Health Assembly. Available online: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-world-health-assembly (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- World Health Organization. Circular Economy and Health: Opportunities and Risks; World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. COP24 Special Report Health and Climate Change; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Nocca, F. Moving towards the circular economy/city model: Which tools for operationalizing this model? Sustainability 2019, 11, 6253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braathen, N. Environmental Impacts of International Shipping, The Role of Ports; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Ambient Air Quality Directives; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019; Volume SWD(2019). [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 9 out of 10 People Worldwide Breathe Polluted Air, but More Countries Are Taking Action. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/02-05-2018-9-out-of-10-people-worldwide-breathe-polluted-air-but-more-countries-are-taking-action (accessed on 5 August 2020).

- European Sea Ports Organisation (ESPO). ESPO Environmental Report 2018. EcoPortsinSights 2018; European Sea Ports Organisation (ESPO): Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Viegi, G. Inquinamento, Clima e Salute Respiratoria: Il Contributo della GARD Italia. Clima, Inquinamento Atmosferico ed Effetti Sulla Salute in Italia. 2019. Available online: http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_EventiStampa_564_3_fileAllegatoIntervista.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2020).

- Watts, N.; Amann, M.; Arnell, N.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; Belesova, K.; Boykoff, M.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Capstick, S.; et al. The 2019 report of The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: Ensuring that the health of a child born today is not defined by a changing climate. Lancet 2019, 394, 1836–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordine dei Medici Chirurghi e Odontoiatri della Provincia diForlì-Cesena Inquinamento Causa il 20% delle Morti in Europa. Ecco il Rapporto ‘Lancet Countdown’. Available online: http://www.ordinemedicifc.it/2020/01/31/inquinamento-causa-il-20-delle-morti-in-europa-ecco-il-rapporto-lancet-countdown/ (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- Re, S. Lancet Countdown: Prognosi Riservata per Clima e Salute Globale. Planet Intelligence. Available online: https://www.scienzainrete.it/articolo/lancet-countdown-prognosi-riservata-clima-e-salute-globale/simona-re/2019-11-21 (accessed on 10 August 2020).

- European Environment Agency. Air Quality in Europe—2019 Report; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019.

- IPCC Global Warming of 1.5 °C; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- World Health Organization. WHO Manifesto for a Healthy Recovery from COVID-19: Prescriptions and Actionables for a Healthy and Green Recovery; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19—21 August 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---21-august-2020 (accessed on 6 September 2020).

- World Economic Forum. The Global Risks Report; World Economic Forum: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Decision No 1386/2013/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 November 2013 on a General Union Environment Action Programme to 2020 “Living well, within the limits of our planet”. Off. J. Eur. Union 2013, 171–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The European Green Deal; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. First WHO Global Confernce on Air Pollution and Health. Improving Air Quality, Combatting Climate Change—SAVING Lives. Clean Air for Health: Geneva Action Agenda; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization—Regional Office for Europe Sixth Ministerial Conference on Environment and Health. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/media-centre/events/events/2017/06/sixth-ministerial-conference-on-environment-and-health/read-more (accessed on 5 June 2020).

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. Parma Declaration on Environment and Health; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization—Regional Office for Europe Health 2020. A European Policy Framework Supporting Action Across Government and Society for Health and Wellbeing; World Health Organization: Copenaghen, Denmark, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization—Regional Office for Europe Protecting Nature Protects Health—Lessons for the Future from COVID-19. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/environment-and-health/pages/news/news/2020/6/protecting-nature-protects-health-lessons-for-the-future-from-covid-19 (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- ATS Milan—Metropolitan city of Milan. Piano Integrato di Promozione Salute; ATS Milan: Milan, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. Valuing Our Communities and Cities; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020; Available online: https://urbanoctober.unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2020-09/Final%20World%20Cities%20Day%202020%20Concept%20Notes%20on%20Valuing%20Communities%20and%20Cities.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- Preston, F. A Global Redesign? Shaping the Circular Economy. Energy Environ. Resour. Gov. 2012, 2. Available online: https://www.chathamhouse.org/sit (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- European Commission, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions; Closing the Loop—An EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015.

- European Commission Report from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. On the Implementation of the Circular Economy Action Plan. 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52019DC0190&from=EN (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- Fusco Girard, L.; Nocca, F. Circular city model and its implementation: Towards an integrated evaluation tool. BDC Boll. Cent. Calza Bini 2018, 18, 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Agenda Stad. The Perspective of the Circular City; Agenda Stad: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gravagnuolo, A.; Angrisano, M.; Fusco Girard, L. Circular Economy Strategies in Eight Historic Port Cities: Criteria and Indicators Towards a Circular City Assessment Framework. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LWARB. London’s Circular Economy Route Map—Circular London; LWARB: London, UK, 2017.

- Circle Economy. Circular Glasgow. A Vision and Action plan for the City of Glasgow. 2016. Available online: https://circularglasgow.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Glasgow-City-Scan.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- Gemeente Rotterdam. Roadmap Circular Economy Rotterdam; Gemeente Rotterdam: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mairie de Paris White Paper on the Circular Economy of Greater PARIS; Mairie de Paris: Paris, France, 2017.

- Williams, J. Circular Cities: Challenges to Implementing Looping Actions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavaleiro de Ferreira, A.; Fuso-Nerini, F. A Framework for Implementing and Tracking Circular Economy in Cities: The Case of Porto. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Toro, P.; Nocca, F.; Buglione, F. Evaluations for a new performance-based approach in urban planning. Arch. Studi Urbani Reg. 2020, 127, 149–180. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Actionables for a Healthy Recovery from COVID-19 Actionables to the Prescriptions of the WHO Manifesto; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/actionables-for-a-healthy-recovery-from-covid-19 (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- Dinerstein, E.; Vynne, C.; Sala, E.; Joshi, A.R.; Fernando, S.; Lovejoy, T.E.; Mayorga, J.; Olson, D.; Asner, G.P.; Baillie, J.E.M.; et al. A Global Deal for Nature: Guiding principles, milestones, and targets. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Wide Fund for Nature—WWF. COVID 19: Urgent Call to Protect; WWF: Gland, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). Nature’s Dangerous Decline ‘Unprecedented’ and Species Extinction Rates ‘Accelerating’; IPBES: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Urban Agenda for the EU Pact of Amsterdam. 2016. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/policy/themes/urban-development/agenda/pact-of-amsterdam.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2018).

- Cohen-Shacham, E.; Walters, G.; Janzen, C.; Maginnis, S. Nature-Based Solutions to Address Global Societal Challenges; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology). COST Action CA17133. Implementing Nature-Based Solutions for Creating a Resourceful Circular City; COST: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kabisch, N.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Pauleit, S.; Naumann, S.; Davis, M.; Artmann, M.; Haase, D.; Knapp, S.; Korn, H.; Stadler, J.; et al. Nature-based solutions to climate change mitigation and adaptation in urban areas: Perspectives on indicators, knowledge gaps, barriers, and opportunities for action. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Nocca, F.; Gravagnuolo, A. Matera: City of nature, city of culture, city of regeneration. Towards a landscape-based and culture-based urban circular economy. Aestimum 2019, 74, 5–42. [Google Scholar]

- Maas, J.; Verheij, R.A.; Groenewegen, P.P.; de Vries, S.; Spreeuwenberg, P. Is Green Space in the Living Environment Associated with People’s Feelings of Social Safety? J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2006, 60, 587–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dravigne, A.; Waliczek, T.M.; Lineberger, R.D.; Zajicek, J.M. The effect of live plants and window views of green spaces on perceptions of job satisfaction. Hortic. Sci. 2008, 43, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, C.M.; Berry, P.; Breil, M.; Nita, M.R.; Kabisch, N.; de Bel, M.; Enzi, V.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Geneletti, D.; Cardinaletti, M.; et al. An Impact Evaluation Framework to Support Planning and Evaluation of Nature-Based Solutions Projects; Centre for Ecology and Hydrology: Wallingford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, D.; Moran, D.; Biller, D. Handbook of Biodiversity Valuation: A Guide for Policy Makers; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Danvers, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Italian Government. Iniziative per il Rilancio “Italia 2020–2022”, Rapporto per il Presidente del Consiglio dei Ministri; Italian Government: Rome, Italy, 2020. Available online: http://www.governo.it/sites/new.governo.it/files/comitato_rapporto.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- Nijkamp, P.; Voogd, H. Conservazione e Sviluppo: La Valutazione Nella Pianificazione Fisica; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. A Monitoring Framework for the Circular Economy; European Commission: Strasbourg, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Level(s): A Guide to Europe ’s New Reporting Framework; European Commission: Seville, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Assessing the Health Impacts of a Circular Economy; WHO: Copenaghen, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, N.; Amann, M.; Ayeb-Karlsson, S.; Belesova, K.; Bouley, T.; Boykoff, M.; Byass, P.; Cai, W.; Campbell-Lendrum, D.; Chambers, J.; et al. The Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: From 25 years of inaction to a global transformation for public health. The Lancet 2017, 391, 581–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, R.K. Speculations on Weak and Strong Sustainability; CSERGE Working Paper; CSERGE: Nowich, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Ruskin, J. The Seven Lamps of Architecture; Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, W. Address to the Annual General Meeting of SPAB. 1889. Available online: www.spab.org.uk (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- Turner, R.K.; Paavola, P.; Cooper, P.; Farber, S.; Jessamy, V.; Georgiou, S. Valuing nature: Lessons learned and future research directions. Ecol. Econ. 2003, 46, 492–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TEEB (The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity). Mainstreaming the Economics of Nature: A Synthesis of the Approach, Conclusions and Recommendations of TEEB; TEEB: Birkirkara, Malta, 2010; Available online: www.teebweb.org (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- Aucelli, P.; Di Paola, G.; Incontri, P.; Rizzo, R.; Vilardo, G.; Benassai, G.; Buonocore, B.; Pappone, G. Coastal inundation risk assessment due to subsidence and sea level rise in a Mediterranean alluvial plain (Volturno coastal plain—Southern Italy). Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2017, 198, 597–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization. World Health Organization, 1948. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/bd/PDF/bd47/EN/constitution-en.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 12 July 2020).

- Dogliotti, E.; Achene, L.; Beccaloni, E.; Carere, M.; Comba, P.; Crevelli, R.; Lacchetti, I.; Pasetto, R.; Sogiu, M.E.; Testai, E. Linee Guida per la Valutazione di Impatto Sanitario (DL.vo 104/2017); Rapporti ISTISAN 19|0; Istituto Superiore di Sanità: Roma, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco Girard, L.; De Rosa, F.; Nocca, F. Verso il piano strategico di una città storica: Viterbo. BDC Boll. Cent. Calza Bini 2014, 14, 11–38. [Google Scholar]

- Lichfield, N. Community Impact Evaluation: Principles and Practice; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Coccossis, H.; Nijkamp, P. Sustainable Tourism Development; Avebury Press: Aldershot, Avebury, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco Girard, L.; Nijkamp, P. Cultural Tourism and Sustainable Local Development; Ashgate: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating Shared Value. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, M.; Lochard, A. Public Policy Labs in European Union Member States; European Union: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Stiglitz, J.; Sen, A.; Fitoussi, J. Report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress. 2009. Available online: www.stiglitz-sen-fitoussi.fr (accessed on 29 September 2020).

- Italian National Institute of Statistic (ISTAT). Il Benessere Equo e Sostenibile in Italia. BES Report 2015; Italian National Institute of Statistic (ISTAT): Rome, Italy, 2015; ISBN 9788845818769. [Google Scholar]

- Italian National Institute of Statistic (ISTAT). Il Benessere Equo e Sostenibile in Italia. BES Report 2019; Italian National Institute of Statistic (ISTAT): Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R.; Caniglia, E.; Fioramonti, L.; Kubiszewski, I.; Lewis, H.; Lovins, H.; McGlade, J.; Mortensen, L.F.; Philipsen, D.; Pickett, K.; et al. Toward a Sustainable Wellbeing Economy. Solut. J. 2018, 9, 2. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Girard, L.F.; Nocca, F. Climate Change and Health Impacts in Urban Areas: Towards Hybrid Evaluation Tools for New Governance. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 1344. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos11121344

Girard LF, Nocca F. Climate Change and Health Impacts in Urban Areas: Towards Hybrid Evaluation Tools for New Governance. Atmosphere. 2020; 11(12):1344. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos11121344

Chicago/Turabian StyleGirard, Luigi Fusco, and Francesca Nocca. 2020. "Climate Change and Health Impacts in Urban Areas: Towards Hybrid Evaluation Tools for New Governance" Atmosphere 11, no. 12: 1344. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos11121344

APA StyleGirard, L. F., & Nocca, F. (2020). Climate Change and Health Impacts in Urban Areas: Towards Hybrid Evaluation Tools for New Governance. Atmosphere, 11(12), 1344. https://doi.org/10.3390/atmos11121344