1. Introduction

Climate change will increase the frequency and severity of natural catastrophes [

1], causing direct damage to built environments and agricultural land, as well as indirect economic impacts, through trade- and supply-chain disruptions, lower productivity, and loss of income [

2]. Furthermore, large natural catastrophes can have economic impacts on the financial market. For example, the demand for capital that is needed to rebuild assets after a natural catastrophe can cause the price of capital to rise, which can increase the cost of insurance as insurers are trying to recapitalize after large amounts of claims are paid [

3]. The vulnerability of the insurance sector, due to remote catastrophes that occur outside the EU, can have directly-felt consequences for households in EU countries regarding coverage and costs, which will be the main focus of this study.

Insurance is a way to enhance financial resilience against damage caused by natural events, as it is found to increase the certainty of adequate financial compensation after an event and therefore increases the speed of recovery [

4,

5]. However, premiums for insurance against natural disasters are expected to rise in the future as a result of climate change [

6], which can cause it to become unaffordable for certain population groups, or it can exceed the willingness-to-pay for insurance. This means that insurance uptake can decline in markets where purchasing flood coverage is optional. It is therefore important to assess under which conditions insurance premiums are affected by climate change and to understand how to limit potential increases in premiums.

The insurance industry aims at absorbing individual losses by spreading risk over time and space. This means that the risk of individual insurance companies becoming insolvent declines with the geographical spread of its policyholders, thereby creating a larger risk-pool with lower correlated risk. By calculating average risk over time, the insurance mechanism can transform a large financial shock due to a disastrous event into a manageable annual premium. As the primary insurer’s ability to spread its risk is often limited geographically by, for example, national borders, large-scale natural catastrophes can jeopardize the solvability to settle indemnity payments. Therefore, the insurer can choose to transfer part of its risk portfolio to a reinsurer. An often-used mechanism for this is excess-of-loss coverage, where reinsurance coverage steps in when a certain threshold of insurance claims has been made. Therefore, the reinsurer deals with the most extreme risks, which are events that occur with low probability but have a high impact. In order to maintain a manageable risk portfolio the reinsurer often operates on a global level, and due to scale-advantages on this level, the market is dominated by few firms compared to the market for primary insurance [

7]. As a result, there is limited competition in this market, which can cause reinsurance premiums to be several times the actuarial price of the underwritten risk [

8].

The reinsurance premiums generally fluctuate due to underwriting cycles, which are periods of rising and falling underwriting profits as a result of fluctuating prices of coverage [

3]. Internal forces of supply and demand cause these fluctuations, where periods of increased competition between reinsurers and products leads to declining premiums and an expansion of coverage. Due to lower returns on the underwritten risk and declining profitability, some (re)insurers will withdraw from the market, at which point competition decreases and premiums rise. When profitability is restored, new insurers and products will enter the market, and the cycle starts over again [

9].

In addition to inherent cycles in the market for risk financing, price fluctuations can arise due to external events such as large natural- or man-made catastrophes, which may cause a reinsurer’s capital stock to deteriorate. Consequently, the demand for capital increases, resulting in higher prices demanded by investors and, ultimately, rising reinsurance premiums [

7,

8]. Resulting from an increase in the return on capital, however, the supply of capital increases, causing the reinsurance premium to decline again. Therefore, a determining factor for the reinsurance premiums is the availability of capital. When capital is scarce as a result of large-scale demand after a natural- or man-made catastrophe, market forces lead to what is referred to as a “hard” market for capital, where the price of capital rises [

10]. Reinsurance premiums can decline again in a “soft” market, which is a result of the increasing supply of risk coverage [

11]. As reinsurers usually operate worldwide, and there are often multiple reinsurers engaged in an area affected by a natural disaster, these conditions can be transmitted to primary insurers across the globe [

12]. Past experience supports that, as a result of rising reinsurance costs in a hard capital market, premiums for natural disaster insurance can increase. The OECD (2018) [

13] found a high correlation (79%) between property catastrophe reinsurance pricing and rates of primary insurance against natural hazards in the US.

Looking at further empirical evidence of this relationship, 2005 was a very costly year for property insurance due to three hurricanes that made landfall in the US (Katrina, Rita and Wilma with a combined loss of

$79 billion) [

14]. As a result, reinsurers were forced to recapitalize and the Global Rate on Line (RoL) Index, an annual measure of change in property catastrophe reinsurance premiums, increased by 36.6% [

15]. The following two years had no major natural disasters and, as a result, the capital of reinsurers is largely replenished and reinsurance premiums are in decline [

13]. The next rise in reinsurance premiums resulting from a natural disaster occurs in 2011, mainly as a result of the Tohoku earthquake (

$40 billion insured losses [

16]) and consequent tsunami in Japan, which led to an increase in reinsurance premiums of 9.5% [

15]. These examples, from practice, show how hard reinsurance markets did arise in the past, despite the practice of reinsurers to spread various types of risks, including both catastrophe and non-catastrophe risk portfolios. For example, a reinsurer’s risk portfolio can, besides the risk of natural hazards, also contain underwritten life- and health-risks. In this study, we emphasize the impact of natural disasters on capital market volatility for reinsurers, as the risk of natural disasters is found to be increasing as a result of climate change. However, a hard capital market for reinsurance could also be triggered by other events, such as an outbreak of an epidemic disease. It is noteworthy that we do not distinguish between the types of disasters and events that trigger a hard capital market and hence do not consider risk spreading over different types of risk portfolios. Instead, we examine the implications of hard market conditions arising in the future, as they have occurred in the past, for flood insurance premiums and other relevant indicators of the performance of flood insurance markets.

This study progresses on the previous study by Tesselaar et al. [

17] by investigating the impact of soft and hard reinsurance markets for natural disasters, in addition to the impact of climate change, on flood insurance in the EU. The frequency and severity of natural catastrophes is increasing worldwide, which can lead to more occurrences of a hard market in the future, causing insurance premiums within the EU to be higher than expected. Rising insurance premiums for natural hazards, such as flooding, increase the basic living expenses of households, which may reduce a certain standard of living after obtaining insurance coverage. As shown by Tesselaar et al. [

17], who projected the impact of climate- and socio-economic change on flood insurance premiums in the EU, insurance can become unaffordable for lower income groups. Also, when natural hazard insurance is optional, rising premiums may discourage individuals from obtaining coverage, leaving them more financially vulnerable to the impact of natural disasters [

18]. Therefore, we aim to show how conditions for the EU flood insurance market are dependent on global disasters, and what the possible outcomes are in terms of the premiums, unaffordability, and uptake of flood insurance for private households. By using the “Dynamic Integrated Flood Insurance” (DIFI) partial equilibrium model [

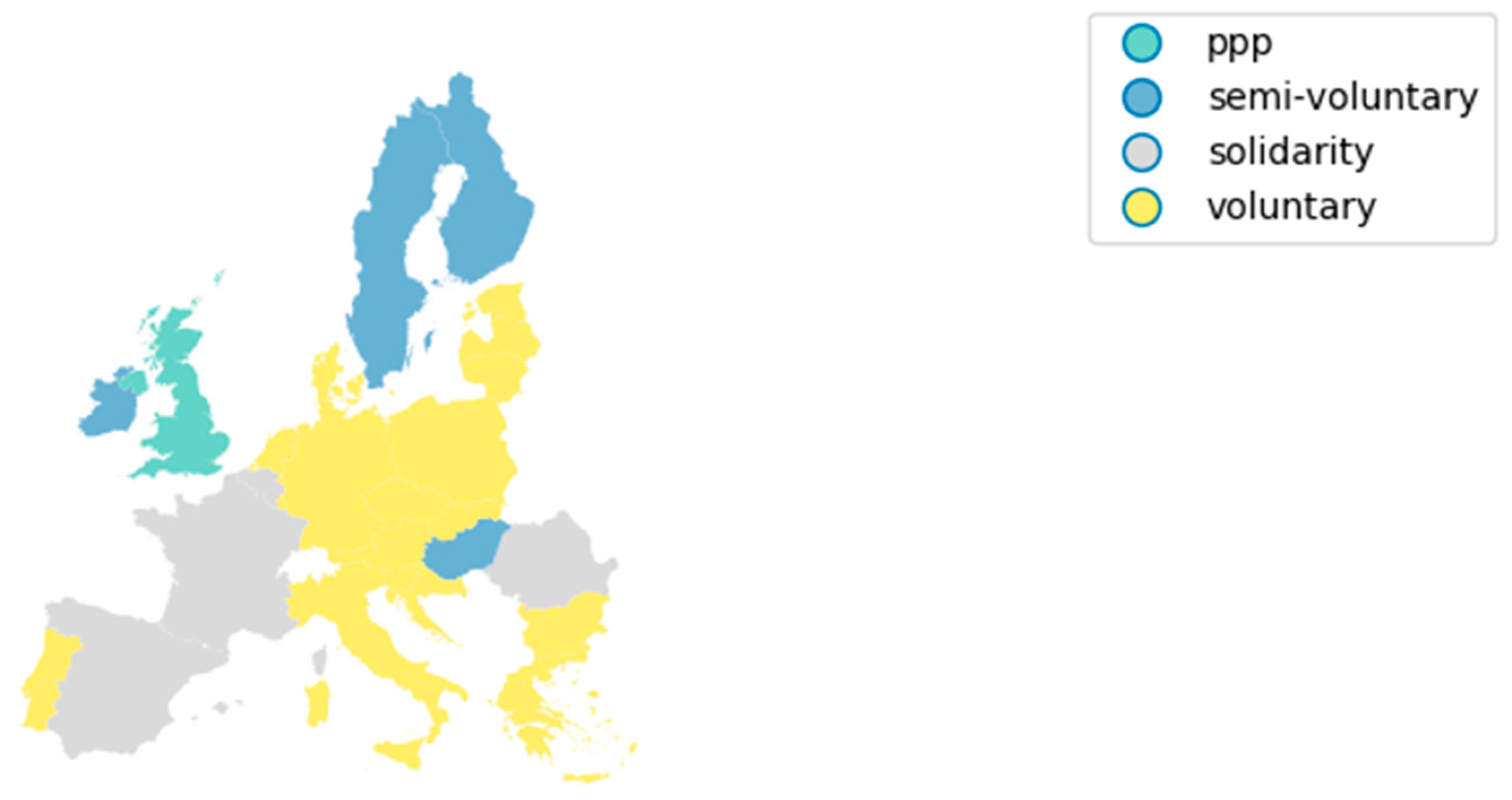

19], we estimate flood insurance premiums for different stylized flood insurance systems under various scenarios of climate change, and we project the impact of a hard or soft reinsurance market on this outcome. Most EU countries currently maintain a (semi-) voluntary system for flood insurance, where primary insurers obtain excess-of-loss coverage from private reinsurers and are therefore subject to developments on the international reinsurance and capital market [

19]. In the case of a hard market, the cost loading factor of the reinsurer is higher than in a soft market, causing the insurer to charge a higher premium for coverage.

In the following section, we elaborate on the applied methodology, after which we present the results. Then, we discuss the implications of the findings and conclude the paper.

3. Results

Here, we show the projected effects of reinsurance market volatility on flood insurance premiums, the unaffordability of insurance, and the market penetration rates. Unaffordability is shown as the absolute value of the unaffordable share of the premiums, as well as the percentage of the population for whom flood insurance is unaffordable. We show the output for two projections of climate- and socio-economic change: namely, RCP4.5-SSP2, which is roughly aligned with a 2-degree Celsius temperature rise and an average socio-economic development worldwide [

44], as well as RCP8.5-SSP5, which is a high-end pathway for greenhouse gas emissions due to a high reliance on fossil fuels and high socio-economic growth [

45].

Figure 2, below, shows projected insurance premiums for soft and hard reinsurance capital markets, on a national level, for 2020, 2050, and 2080. The premiums are determined based on the status-quo of national flood insurance systems, which is assumed to remain unchanged. Therefore, it can be seen that premiums in countries such as Belgium, Spain, France, and the UK are below average due to more cross-subsidization between high- and low-risk policyholders in their insurance systems (see

Figure 1 for the allocation of insurance systems per country). For countries with (semi-) voluntary insurance systems, premiums are risk-reflective, which causes premiums in high-risk areas to be higher than in areas with a lower risk. Since we show here the results for 1/100-year flood zones, it can be seen that premiums are projected to rise much more rapidly in these voluntary systems compared to countries where flood risk is born collectively. On average, premiums for countries with a solidarity insurance system are projected to rise with a factor 6.5 up to 2080 under hard conditions for RCP4.5, whereas this growth is a factor 9.3 for countries with a voluntary system. Under the RCP8.5 scenario, these growth rates are 15.5 and 24.4, respectively.

The premiums shown in

Figure 2, are higher under the RCP8.5-SSP5 scenario (bottom panels) than under the RCP4.5-SSP2 scenario (top panels), which resonates the development of flood risk under the scenarios. Furthermore, it can be seen that premiums are consistently higher under a hard reinsurance capital market than a soft version (shown in orange and blue colors, respectively). Although the exact ratio of the difference varies between countries, which is dependent on the variance of expected losses (see Equation (1)). For RCP4.5, the average difference in premiums between hard and soft markets for countries with a voluntary system rises from €154 in 2020 to €1710 in 2080. However, extreme differences in projections can be seen for Portugal (PT) and Bulgaria (BG), where the difference in premiums between market states for 2080 is €6500 and €4500, respectively. For RCP8.5, the average difference between capital market states for voluntary premiums rises to €3980 in 2080.

Figure 3 shows the impact of a hard and a soft capital market for reinsurance on the unaffordability of flood insurance for EU countries in 2020, 2050, and 2080. The graph shows the results for countries with (semi-) voluntary insurance arrangements, since these insurance systems are more prone to volatility on the capital market for reinsurers, as coverage is obtained from private reinsurers. Countries with a solidarity-based or a public–private partnership are excluded from later graphs, as these are not impacted by the capital market conditions resulting from remote natural catastrophes, because reinsurance is provided by governments.

Figure 3 shows the difference in the absolute value of unaffordability between a soft and a hard reinsurance market for both flood risk scenarios. For example, for 2020, it can be seen that for Germany (DE), under RCP4.5, unaffordability in a hard reinsurance market is slightly more than €100 million higher compared to a soft market. The large effect of reinsurance market volatility on insurance premiums in the second half of this century for RCP8.5, shown in

Figure 2, can be seen to cause substantial differences in unaffordability when compared to RCP4.5. For example, the difference in the absolute value of unaffordability between soft and hard market conditions grows, on average, for EU countries, with a factor 5.2 for RCP4.5, while it grows with a factor 19.7 for RCP8.5.

Figure 3 shows the sum of the unaffordable share of the premiums, which is an important indicator for national policies that may be implemented to assist low-income households in obtaining flood insurance coverage. Due to a hard capital market, the average value of unaffordability in a country is approximately €15 million higher than for a soft market state in 2080 for RCP4.5, which, for RCP8.5, becomes €55 million. The largest difference in unaffordability between the two market states is expected in Germany (DE) in 2080 under RCP8.5, where the value of the unaffordable share of premiums for all households in high-risk areas is €2.2 billion higher under a hard compared to a soft reinsurance capital market. This result is not surprising, as Germany is the largest EU country in terms of population, and is expected to grow further towards 2080, which translates into a high absolute amount of unaffordable premium levels.

Figure 4 shows the unaffordability of flood insurance as a percentage of the population in high flood-risk zones. This indicates the share of the population that cannot afford flood insurance due to budgetary restrictions and which may require government assistance in order to obtain coverage. Unaffordability is shown for both soft and hard reinsurance market conditions in order to show the difference between the two market states, in addition to the extent of projected unaffordability as a result of climate- and socio-economic change. It can be seen that the percentage of the population that cannot afford flood insurance increases overall, as a result of climate- and socio-economic change. Under constant soft reinsurance market conditions, the percentage of households in high-risk areas for whom flood insurance is unaffordable rises from 23% in 2020 to 36% in 2080 for RCP4.5, while it rises to 41% under RCP8.5 (see

Figure A1 in

Appendix A). Several countries, including Croatia (HR), Latvia (LV), Poland (PL), and Portugal (PT), show significant increases over time. On average, over these countries, in soft market conditions, unaffordability rises from 30% in 2020 to 53% in 2080. The difference in reinsurance market conditions (the difference between the blue and red bars) shows consistently higher unaffordability under hard market conditions, with a slight variation between countries. Over all regions with (semi-) voluntary insurance, unaffordability is 2.4% higher in a hard compared to a soft capital market, which is relatively smaller than the difference in the absolute value of unaffordability shown in

Figure 3. This is because most of the increased value of unaffordability in a hard market is a burden for households for whom insurance was already unaffordable in a soft market. In other words, the hard market adds to the total amount of unaffordability of premiums, but less to the share of the population who cannot buy insurance because it is unaffordable.

In

Figure 4, it can be seen that the high absolute value of unaffordability in Germany, as shown in

Figure 3, is shared amongst a much larger population than in, for example, Portugal, where the percentage of the population for whom flood insurance is deemed unaffordable is higher. In Portugal, for the RCP4.5 scenario, this projected percentage rises from 52% in 2020 under a soft market to 75% in 2080, which for a hard market becomes a rise from 54% to 78%. For several countries, the percentage of households for whom insurance is unaffordable remains low and changes only slightly (e.g., Austria (AT), Denmark (DK), the Netherlands (NL)), which is due to a combination of the low growth of riverine flood risk and the high projected income growth in these regions. The highest percentage of unaffordability is observed in Bulgaria (BG), where risk-based premiums are expected to be unaffordable for approximately 96% of the households located in high-risk areas in 2080 for both market states.

As affordability is a condition for insurance uptake, consistent with results shown in

Figure 4, the projected insurance penetration rate in Bulgaria is low, as shown in

Figure 5. In fact, the model estimations show a decline in insurance uptake from 12% in 2020 to merely 3% in 2080, for soft market conditions under RCP4.5. For other countries, while the projected uptake of insurance remains higher, a significant decline can be observed (e.g., Croatia (HR), Latvia (LV), Poland (PL), and Portugal (PT)), which is a result of increasing unaffordability, as well as a lacking willingness-to-pay for premiums that are higher due to climate- and socio-economic change or, as can be seen, due to hard reinsurance market conditions. For the five countries with the highest change in penetration rates, the uptake declines from 28% in 2020 to 13% in 2080 for soft market conditions under RCP4.5, which is much higher than the average decline over all countries with a voluntary system (34% to 30%). The difference between hard and soft reinsurance market conditions is, on average, in the countries in

Figure 5, less than 1% in 2080, which is lower than unaffordability as a percentage of the population shown in

Figure 4. This is because, for each modeled household, if the premium becomes unaffordable due to a hard reinsurance market, its decision to not insure will not affect the penetration rate if it did not purchase insurance initially.

Figure 5 shows the penetration rate for countries where flood insurance uptake is voluntary, which is why several EU countries with non-voluntary systems are excluded from this figure. A problem with voluntary insurance systems, as follows from

Figure 5, is that uptake declines to such an extent that the majority of the population at risk of flooding is not covered by insurance, and is therefore not financially protected against flood risk. Instead of formal insurance, these households may have to rely on private savings or on government support in the case that they experience damage due to flooding. In

Appendix B, we elaborate on the possible extent of required government compensation or private savings to cover uninsured flood damage for EU countries with voluntary insurance systems.

4. Discussion

Volatility on the global capital market for reinsurance, as a result of large catastrophes can have substantial consequences for flood insurance premiums and the unaffordability thereof. We showed the projected development of flood insurance premiums towards 2080 and presented the fluctuation of premiums due to hard and soft capital market conditions for reinsurance, as defined by Kunreuther et al. [

11]. Moreover, we plotted the difference in unaffordability and the uptake of flood insurance under hard and soft capital markets for reinsurance and under various scenarios of climate- and socio-economic change. The results of our modeling exercise show a steep increase in insurance premiums towards 2080 and a significant impact of capital market conditions, which is especially evident under the high-end scenario RCP8.5-SSP5. The impact of capital market conditions for the reinsurer can cause considerable changes in the unaffordability of, and the demand for, flood insurance, which can have further repercussions for households that may have to stop insuring and rely on government compensation or private savings in the case that flood damage occurs.

In order to enhance the financial resilience of households to flooding, governments can impose insurance purchase requirements. For example, high penetration rates of flood insurance for households in Sweden (>95%) is a result of uptake being compulsory for household mortgages [

46]. Similarly, France attains a penetration rate of 100% by including flood damage coverage in general property insurance and by keeping premiums low for high-risk households due to full risk-sharing amongst its population [

46]. However, in the absence of flood risk cross-subsidization, which may have low political support due to the higher financial burden for households in low-risk areas [

19], households may not be able to afford the premium. For these households, it may be required by governments to cover the unaffordable share of premiums in the form of subsidies or, as proposed by Kousky and Kunreuther [

5], a means-tested voucher, which preserves the incentive for applying risk-reduction measures. From our analysis, it follows that climate change and hard reinsurance capital markets have a relatively small effect on the number of households for whom flood insurance is unaffordable (see

Figure 4). However, we find that the degree of unaffordability increases for households for whom insurance was already unaffordable (see

Figure 3), which means that, under a system such as the one proposed by Kousky and Kunreuther [

5], a higher financial burden is placed on the government to pay for the subsidy systems.

Moreover, in order to improve the affordability of flood insurance, a government can act as a reinsurer. Governments are generally more risk neutral than private reinsurers, can borrow money on the capital market at lower costs than private (re)insurers, and have alternative funding mechanisms, such as ex post taxation, at their disposal, which makes them less reliant on international capital markets for underwriting flood risk [

34]. This type of arrangement is applied in France, where flood risk is covered by private insurers who pass a proportion of the collected premiums to a government backed reinsurer, the CCR (Caisse Centrale de Reassurance), depending on how much it reinsures on the private market [

6]. A similar system exists in Spain, where all natural hazards are covered by a publicly backed insurer, the CCS (Consorcio de Compensacion de Seguros) [

6]. The recently established Flood-Re in the UK in effect performs as a reinsurance pool for high-risk households in order to facilitate premium cross-subsidization. For every underwritten flood risk, a share of the premium is paid to this fund in order to cover damages for approximately 500,000 households residing in high-risk areas [

47]. The underwritten risk for households in lower risk areas are still privately reinsured in the UK.

A noteworthy topic for discussion is that evidence indicates lower reinsurance market volatility resulting from large losses such as natural disasters over recent years [

13]. For instance, although 2017 was the most costly year in history in terms of insured damage, reinsurance premiums hardly increased as a result of the recapitalization of (re)insurers [

48]. The persistence of a soft market is argued to be due to several factors, including low interest rates, which stimulate capital providers, such as pension funds, to invest in various new forms of reinsurance, such as catastrophe bonds, insurance-linked securities (ILS), or sidecars, which still provide relatively high returns [

48]. Besides this, increased capital mobility and flexibility as a result of globalization and technological improvements has largely flattened the cyclic pattern, as money can quickly flow in response to increased returns due to capital shortages [

49].

The abundant supply of capital in response to large losses incurred by reinsurers is, however, largely a result of the financial policies of fiscal institutions, which have been maintaining low interest rates since the financial crisis of 2008 [

50]. This, in combination with the absence of large catastrophes in the period 2011–2017, led to a high supply of alternative capital [

48]. The costly year 2017 did not immediately result in the hardening of the capital market, however, it has been found that the “loss creep”, which is the delayed payment of insurance claims due to bureaucratic obstructions, on top of costly disasters in 2018, such as typhoon Jedi in Japan and wildfires in California, are pressuring capital availability for reinsurance companies, which is possibly an end to years of soft reinsurance conditions [

48].

It should be noted that, although we portray a scenario of a large natural catastrophe that remotely triggers a hard capital market for reinsurance, in our analysis we do not distinguish between events that may cause this situation. While evidence suggests that large natural disasters are an important driver for capital market conditions and, subsequently, rising reinsurance premiums, other types of events, such as terrorist attacks or economic crises can similarly trigger a hard capital market for reinsurance [

13]. Furthermore, in our analysis, we do not explicitly distinguish between remote or local events that cause insurance premiums in the EU to rise. However, the portrayed scenario, where premium setting rules for reinsurers are affected, while those for primary insurers are unchanged, is unlikely to occur after a local catastrophe. For a locally occurring catastrophic event, the primary insurer will also attempt to recapitalize and regain profitability by raising premiums [

51], which causes flood insurance premiums to rise by more than what we considered in this study.

In addition to the previous points of discussion, we want to address the interpretation of the presented results, especially concerning the focus areas of this study, which are current 1/100-year floodplains in EU countries. These areas are expected to experience a high growth in flood risk, which causes problems with the unaffordability and uptake of insurance to be particularly evident there, when premiums are risk-based and uptake is voluntary. Therefore, the results shown in this study represent modeled outcomes for these areas combined per country, and not total national averages.

As climate change is found to increase the frequency and severity of natural catastrophes on a global scale, hard capital markets for reinsurers may occur more often in the future. This study shows that, besides an increasing flood risk within the EU, a hard capital market for reinsurance, as a result of catastrophes that can occur worldwide, can have significant impacts on flood insurance markets within the EU. Previous studies addressing the feasibility of flood insurance in a changing climate have mainly focused on the impact of increasing flood risk within the EU [

19,

52,

53]. This research shows how global interlinkages through the reinsurance market can cause difficulties for EU flood insurance markets, in addition to the more frequently studied impacts of climate change on flood risk in the EU.

5. Conclusions

In this study we addressed the impact of climate change on EU flood insurance markets by focusing on the influence of global reinsurance and capital market volatility. Due to a severe catastrophe, or multiple catastrophes in close succession, a high demand for capital by (re)insurers may trigger a “hard” international capital market for reinsurance, where investors raise the price of capital. As a result, reinsurers and, consequently, primary insurers who reinsure on international markets, raise their premiums, due to which the catastrophe can also have an effect on consumers in countries where the catastrophe did not occur.

In this study, we focused on the extent to which flood insurance premiums change in the EU as a result of a global hard capital market compared to a soft market for reinsurers. We find that the impact of a hard market on flood insurance premiums, for EU countries where flood insurance is privately reinsured, becomes higher due to climate change as a result of an increasing average, and variance of, flood risk. Higher premiums cause more unaffordability and a lower market penetration of flood insurance in countries where this is optional. Consequently, a larger uninsured population implies lower financial resilience to possibly larger and more frequent flood events in the future, where households have to rely on private savings, or on uncertain and perhaps partial government compensation, to cover the damage. Dependent on the willingness of governments to provide flood damage compensation, the burden for public budgets may increase significantly, as shown in this study. The additional burden for governments may diminish funds from other welfare enhancing objectives. Moreover, insurance purchase requirements, which are a possible solution to low market penetration, may require large sums of public money to subsidize unaffordability. Introducing a public reinsurer may reduce flood insurance premiums, as governments are able to borrow money at lower rates and are less prone to capital market volatility.

As climate change is expected to increase the frequency and severity of natural catastrophes worldwide, it is likely that hard capital markets as a result of remote natural catastrophes will occur more often in the future. We have projected the impact of this for EU flood insurance markets and proposed potential solutions to improve the performance of flood insurance in the face of climate change. Future research can further elaborate these policy proposals and investigate in more detail possible other indirect impacts of increasing flood risk, such as business interruption and lost tax revenues, as well as policy solutions to limit such adverse effects.