Abstract

The aim of the research was to determine the effect of graduation towers on the aerosol concentration and its composition not only in the vicinity of the graduation tower itself, but also at a distance from it, on the example of the brine graduation tower in the Wieliczka Salt Mine health resort. Two measurement sites were selected for the research, one located inside the graduation tower and the other at the guard booth—at a considerable distance from the graduation tower. Total suspended particulate (TSP) and PM10 (particulate matter with a diameter that does not exceed 10 µm) samples were taken simultaneously using the aspiration method. The collected samples were subjected to analyses of TSP and PM10 concentrations, the content of organic carbon (OC), elemental carbon (EC) and selected ions. It was confirmed that the composition of the aerosol in the Wieliczka Salt Mine significantly differs from the typical aerosol composition in inland locations and is similar to the aerosol composition in coastal zones. The comparison of the aerosol composition at both measuring sites clearly indicates a very favorable influence of the brine graduation tower on the composition of the atmospheric aerosol, even at a certain distance from it.

1. Introduction

A graduation tower is a structure made of wood and blackthorn branches, used to increase the salt concentration in brine by partial evaporation. In the past, graduation towers were used to produce table salt by evaporating the brine, but nowadays, they have been used to increase air humidity and they serve health and wellness purposes [1,2]. The air is cleaned from particles and water evaporation results in a temperature drop. The humid air moisturizes the respiratory tract and is used for inhalation therapies [3,4]. Graduation towers are usually built in the form of long, several meters high buildings, up to several hundred meters long. The interior of the wooden structure is filled with bundles of blackthorn twigs, on which brine flows from above, breaking against individual twigs. There is usually a brine collection pool under the graduation tower. The aim of the whole process is to obtain at least 16% (maximum approx. 27% [5]) of NaCl solution in water [6,7]. The setting process is highly dependent on the weather. On a sunny and windy day, evaporation is the most intense, which gives the best results; on rainy and foggy days, it hardly attains any concentration. On unfavorable days and at night, the brine supply is disconnected.

Originally, in the 17th and 18th centuries, brine was poured with shovels on wooden structures covered with blackthorn twigs, which splashed on the twigs and ran down to the reservoir under the graduation tower. This process was repeated many times, which allowed for a higher brine density. Thanks to this procedure, during the brewing process, less thermal energy was used to evaporate the water from the brine and crystallize the salt. The use of pumps allowed for the construction of much higher graduation towers, many hundred meters high. This did not change the principle of operation of the graduation towers, as the brine flowed by gravity down the blackthorn branches. The formation of aerosols rich in salt during production was an undesirable effect, as it led to the loss of salt, while with regard to inhalation, the composition of the aerosol is of the greatest importance. The development of other methods of obtaining salt and the growing importance of balneology in medicine have made the graduation towers a place for inhaling the specific aerosol created in their surroundings. Graduation towers constructed for therapeutic purposes differ slightly from traditional graduation towers. Among all of the towers, the brine flows mainly down the walls that are vertical (that do not widen at the base) to create as much healing mist as possible.

The microclimate around the graduation towers is used in the prevention and treatment of upper respiratory tract diseases, sinusitis, emphysema, arterial hypertension, allergies, vegetative neurosis and in the case of general exhaustion [8,9,10,11,12,13]. Graduation towers, in a similar way to the interiors of subterranean salt chambers, support the treatment of people suffering from chronic pneumonia, bronchitis, diseases of the upper respiratory tract and allergies [14]. In addition, staying in the towers and breathing clean air with salt particles is also recommended for healthy people, especially for children and seniors [15,16,17,18], as well as for those living in cities or near busy roads or in areas with smog episodes. Brine inhalations cleanse the respiratory tract, moisturize the mucous membranes, and soothe inflammation.

It should also be emphasized that the brine graduation tower is not only a specific microclimate within the facility itself, but also determines the quality and chemical composition of the air, both within the graduation tower itself, as well as outside its area.

There are increasingly more graduation towers in Poland. They are not only present in some health resorts, such as Wieliczka, Busko-Zdrój, Inowrocław, Rabka-Zdrój and the largest in Europe and the oldest (19th century) still active Polish graduation tower located in Ciechocinek (Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship) [19,20,21], but also in many other cities (Warsaw, Łódź, Bełchatów, Płock, Puławy, Radom, Toruń, Trzebnica, Rzeszów and Silesian cities [22,23]).

The objective of the research was to determine the effect of graduation towers on the aerosol concentration and its composition not only in the vicinity of the graduation tower itself, but also at a distance from it, on the example of the brine graduation tower in the Wieliczka Salt Mine health resort.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling Site

The study was performed at the Wieliczka Salt Mine health resort with its graduation tower, the contractor of which was Skanska. The wooden construction graduation tower measures approximately 53 × 69 m and has an area of 7500 m². The entire structure, with a 22.5 m high octagonal observation tower, forms part of the structure of the building and refers to the no longer existing cooling towers. The health-promoting brine water extracted from the interior of the Wieliczka Salt Mine flows down the larch structure of the graduation tower, spreading a healing salt breeze around it.

The samples were collected in the following two measuring sites: one located inside the brine graduation tower and the second (remote site) located approx. 350 m from the graduation tower at the guard booth at the Daniłowicz Shaft. The dust collector was placed on the landing to ensure that the measuring head was located at an appropriate height (approx. 2.5 m above the ground level). At each of the measurement points, a total suspended particulate (TSP) sample and a PM10 atmospheric aerosol sample (liquid and solid particles with an aerodynamic equivalent diameter that does not exceed 10 µm) were taken simultaneously. In each case, the measurements were repeated five times.

2.2. TSP and PM10 Sampling

It was planned to test about 10–16 m3 of air in a single measurement. This value, assuming a standard flow of 2.3 m3/h for measurements carried out in accordance with PN-EN [24,25,26,27,28,29], allows for continuous sampling of the aerosol for 7–8 h, i.e., in the period covering most of the time when the brine concentration pool is open during the day for patients/guests. [30,31].

Total suspended particulate and PM10 atmospheric aerosols were chosen for this investigation, as the study was aimed at smaller fractions, which seemed to be more appropriate in determining the adverse effects of the object on human health. However, this aspect is very interesting and in future research, we will also consider the chemical composition of finer aerosol fractions.

It is evident that the smaller the size of the dust particles, the greater their harmfulness. Dust particles larger than 10 µm generally do not enter the lungs via air, but end up in the throat and nose. The healing properties of graduation towers are related to the purification and moisturizing of the nasopharyngeal cavity and the reduction in inflammatory reactions and allergies due to the salts contained in the surrounding aerosols. Therefore, TSP and PM10 atmospheric aerosols were selected for this investigation. Thus, studies on smaller fractions seemed more justified in determining the adverse impact of the object on human health and this aspect will be taken into account in future studies.

Aerosol sampling was performed from 19 August to 2 September 2015 using the aerosol sampling devices MVS6D produced by Atmoservice (Poznań, Poland). These aspirators consist of a pump equipped with a motor and an electronic flow rate microcontroller, a temperature and air pressure sensor and measuring heads (separately for TSP or PM10 head). Aerosol samples were collected on quartz filters (Whatman, QMA, ø47 mm, CAT No. 1851-037). The weights of the aerosol samples collected on the filters were determined by weighing the filters on a MYA 5.3 Y.F microbalance with a resolution of 1 µg (Radwag, Poland), before and after exposure. Before weighing, the filters (clean or with a sample) were conditioned under constant conditions in the weighing room for 48 h (constant humidity 45 ± 5% and air temperature 20 ± 2 °C). All the operations related to the conditioning of the filters were carried out in a stream of sterile air inside the laminar chamber.

After taking aerosol samples and conducting gravimetric analysis, a slice from each collected sample was taken for determining the content of organic (OC) and elemental carbon (EC) in the aerosol, while the rest were analyzed for the content of selected ions.

2.3. Chemical Analyses: QA/QC

Organic (OC) and elemental (EC) carbon content analysis was carried out using a reference OC/EC thermal-optical method with the application of the Sunset Laboratory Inc. instrument (Portland, OR, United States). It is a method recognized by NIOSH (the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health) for determining OC and EC in the mass of aerosol deposited on filters (1.5 cm2 samples). The analysis was performed using the “EUSAR-2” protocol [32]. The measurement performance was controlled by systematic calibrating of the analyzer within the range for the determined concentrations and by analyzing standards with certified carbon content (RM 8785 and RM 8786, NIST, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and the blank samples [33,34]. The detection limit for total carbon (TC), computed after analyzing the 26 blanks, was 0.52 μg C/cm2 (0.43 and 0.09 μg C/cm2 for OC and EC, respectively). The standard recovery was from 98 to 122% of the certified value for OC and from 95 to 116% for EC (the certified values were taken from the IMPROVE program).

The remaining part of each sample, the aerosol deposited on quartz filters (sample reduced by the cutout for OC and EC content), was placed in extraction containers (ROTH brand). A total of 25 mL of deionized water was added to each extraction vessel and tightly screwed to prevent leakage during extraction. Then, the extracts were sonicated in an ultrasonic bath (60 min) at a temperature that did not exceed 15 °C. Furthermore, the extraction containers were placed on a mechanical shaker and shaken overnight in a room (about 18 °C) at 60 cycles per min. The extracts were filtered through a microporous filter (CRONUS brand with a PES membrane with a porosity of 0.2 µm).

The selected ions (Cl−, NO3−, NO2−, Br−, PO43−, SO42−, F−, I−, Na+, NH4+, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+) collected on the filters were extracted in water and the obtained water extracts were analyzed by ion chromatography. The ion chromatograph Metrohm (Metrohm AG, Herisau, Switzerland; equipped with an 818 IC pump, 819 IC detector, 837 IC eluent degasser, 830 IC interface; 820 IC separation center) and Metrodata 2.3 software were used for determinations. The method was validated against the CRM Fluka product nos. 89,316 and 89,886; the standard recoveries were from 92% (Na+) to 109% (Cl−) of the certified values, and the detection limits were from 10 ng/cm3 for NH4+ to 27 ng/cm3 for NO3− and Na+ [34].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. TSP and PM10 Concentrations

Inside the graduation tower, TSP concentrations are very high. During the parallel measurements at the remote site, the concentrations were, on average, 18 times lower (Table 1). The TSP concentrations measured at the remote site were constant from day to day, while those measured inside the graduation tower dropped sharply in the following days of the measuring period. This may be the effect of a significant increase in wind speed during this period [35]. PM10 concentrations measured in the analogous configuration of the measurement points were similar in both places (Table 1). On each measurement day in the brine graduation tower, the PM10 concentrations were slightly higher than at the remote site; however, the average concentration ratio was not higher than 1.5. In general, the average PM10 aerosol concentration outside the graduation tower in the Wieliczka Salt Mine can be considered low. It is caused, among others, by the atmospheric and emission conditions that prevail in the summer in this region, which are not conducive to the accumulation of pollutants in the atmosphere [36,37,38,39]. Higher PM10 concentrations inside the graduation tower are most likely the result of the presence of fine brine droplets in the dispersed phase of the aerosol. For comparison, data on PM10 concentrations in various other regions of Poland from a similar research period, including the summer season, can be cited. For example, in the atmospheric air in the area of the so-called Green Lungs of Poland, in the Borecka Forest in the north of Poland, the average annual aerosol concentration is only about a dozen percent lower; similar PM10 concentrations were recorded in the summer and autumn in the Gdańsk coastal zone of the Baltic Sea [40]. On the other hand, in cities in the south of the country, e.g., in Kraków, its concentrations were much higher [41].

Table 1.

Mean concentrations of TSP, PM10 and organic carbon OC and elemental EC associated with these fractions and the ratios of selected values.

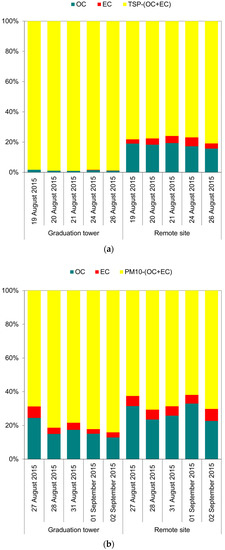

3.2. OC and EC Concentrations

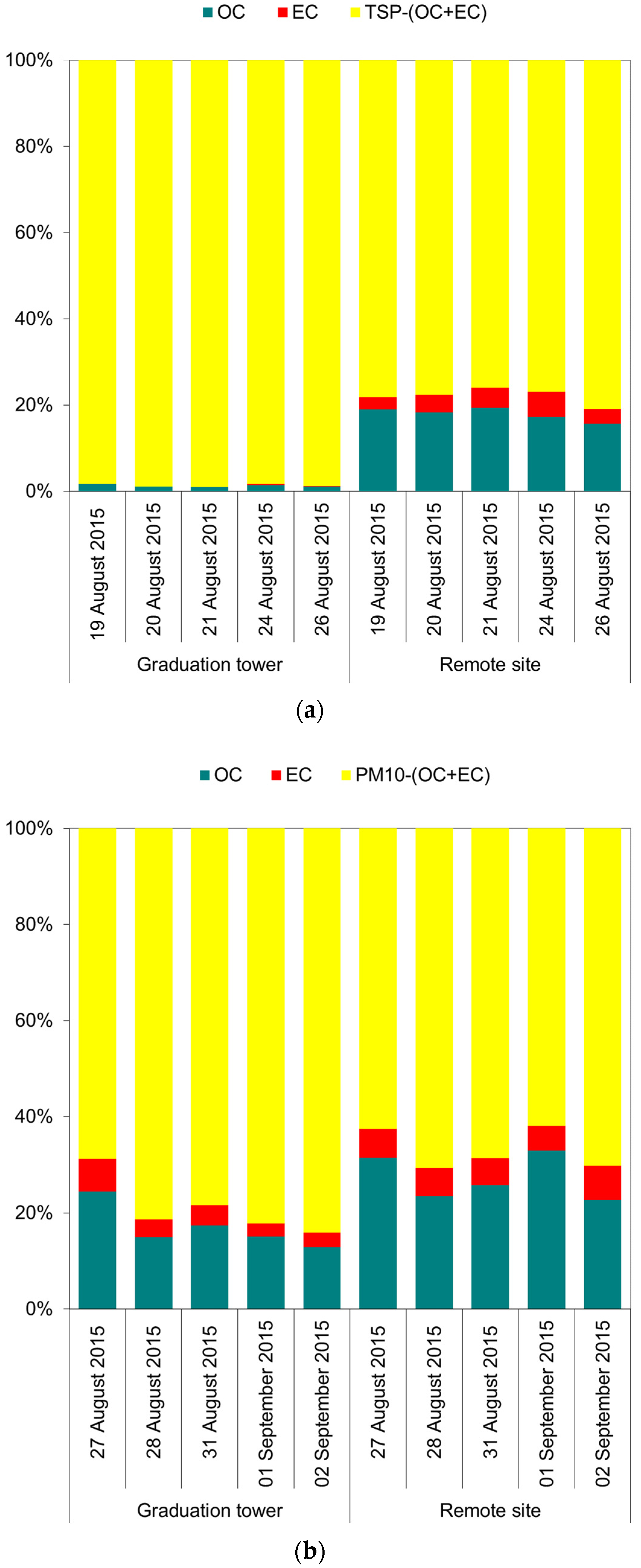

The concentrations of organic carbon (OC), as well as element carbon (EC), in the TSP, regardless of the differences in the mass concentrations of the aerosol itself, were very similar at both measurement points (Table 1). The carbon compounds present in the air are the result of anthropogenic emissions, which are most often emissions related to the combustion of fuels in urban areas in Poland [42,43,44,45]. The effect of air purification from these compounds (carbon compounds) inside the brine graduation tower is clearly visible in the case of the observation of TSP. This aerosol contains practically no carbon compounds in its total weight (Figure 1a). Evidently, this is indirectly due to the large difference in the aerosol mass collected at both points. Nevertheless, the content of carbon compounds per m3 of air was also significantly lower inside the graduation tower than at the measuring point outside it. For example, the ratio of EC concentrations in TSP inside the graduation tower to the EC concentrations in TSP at the remote site was 0.3 (Table 1). The PM10 aerosol inside the graduation tower was not characterized by such strong properties of “washing out” carbon compounds from the air (Figure 1). It seems that finer PM10 particles have similar properties inside and outside the brine graduation tower (Figure 1b and Table 1).

Figure 1.

The contribution of organic (OC) and elemental (EC) carbon in the total mass of the TSP (a) and in the total mass of the PM10 (b).

3.3. Ionic Components

Table 2 shows the concentrations of water-soluble ions related to TSP and PM10 at two measurement points on consecutive measurement days. As expected, the highest concentrations, regardless of the tested fraction, were for Cl−, Na+, SO42−, and NH4+. Regardless of the fluctuations in the concentration of TSP in the air and the concentrations of ionic components of this aerosol in the consecutive measurement days, both in the brine graduation tower and at the remote site (Table 2), the proportions of the concentration of ionic components associated with both fractions of the aerosol are quite aligned over the entire measurement period. Therefore, it is possible to assume that chloride concentrations in the graduation tower in the Wieliczka Salt Mine are, on average, about 19 times higher than outside it and the sodium concentrations are also 10 times higher, etc. It is clearly visible that TSP in the graduation tower is very strongly enriched in fluorides, iodides and bromine compared to the aerosol outside the graduation tower. This equalization of the concentration ratios of ionic components inside and outside the graduation tower probably means that the dominant role in shaping the chemical composition of the aerosol inside the graduation tower must be played by the conditions inside it, and thus de facto the brine composition [46].

Table 2.

Concentration (µg/m3) of ionic components of water-soluble aerosol related to TSP and PM10 in the five-day measurement periods.

Interestingly, even though the concentrations of both PM10 and its ionic components were much more even in the measurement periods at both points than in the case of TSP (Table 2), the ratios of concentrations of the same PM10 components at two points were quite variable in the research period. Thus, it seems that the concentration and chemical composition of PM10 inside the graduation tower is, to some extent, also dependent on the external conditions and the chemical composition of PM10 outside the graduation tower.

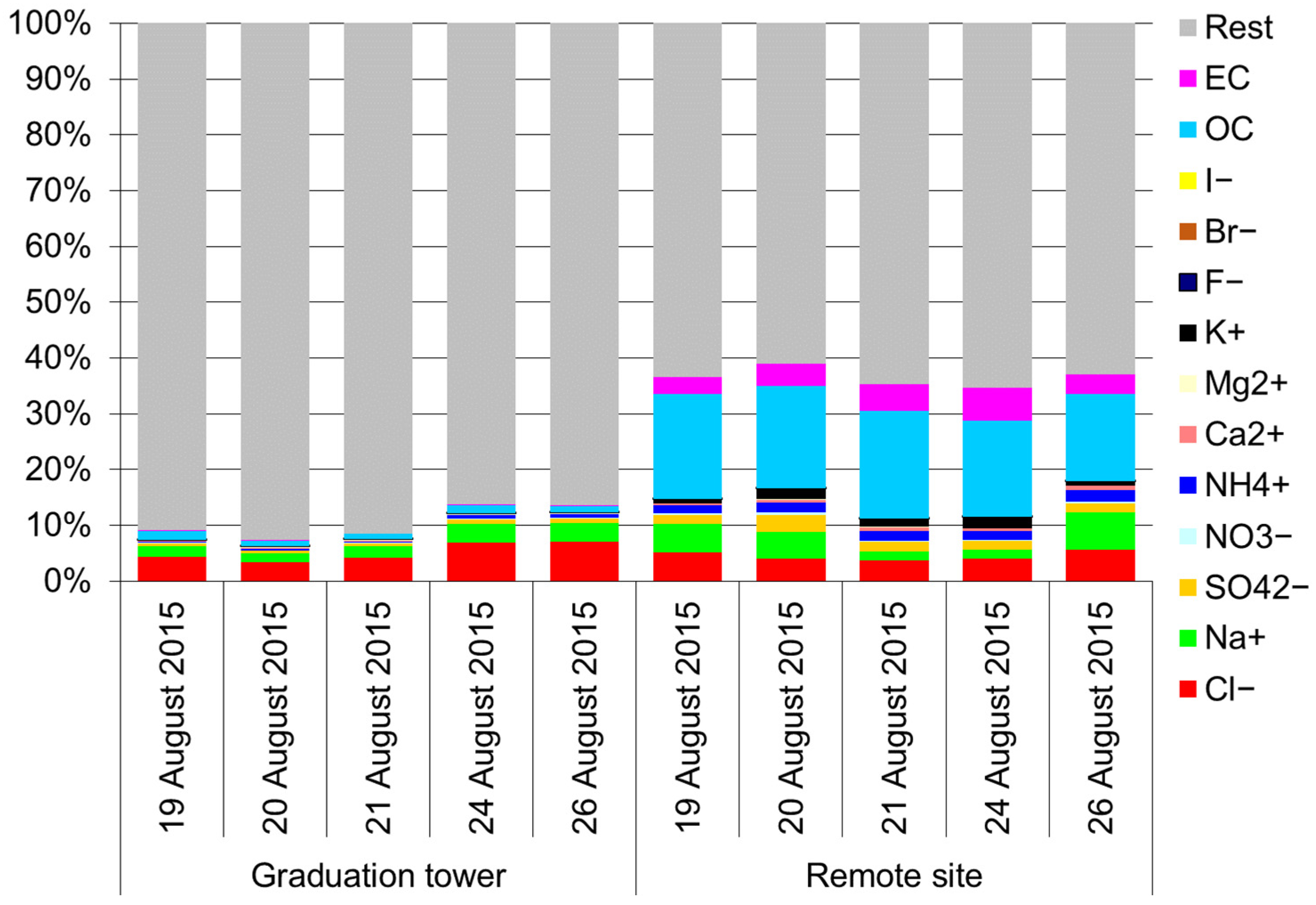

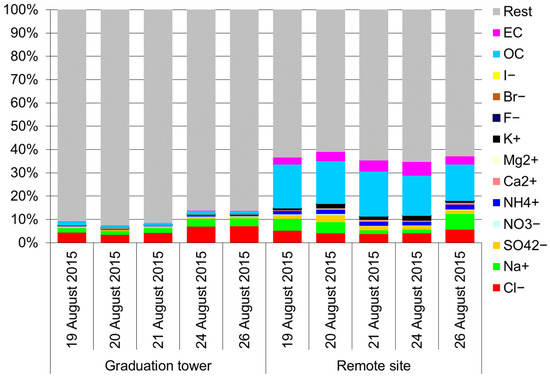

All the determined components accounted for approximately 40% of the TSP mass, except for the brine graduation tower (Figure 2). This is an expected result. In the remote site, TSP consists of approximately 47% of the PM10 fraction (Table 1) and the remaining 50% of the mass may be soil elements and other mineral substances and road dust [47,48]. This matter, not determined in the described experiment, is the building material of large particles of atmospheric aerosols. Thus, it is obvious that the aerosol constituents designated here contribute to the much higher mass of PM10 compared to TSP.

Figure 2.

Mass percentage of various components in the TSP mass.

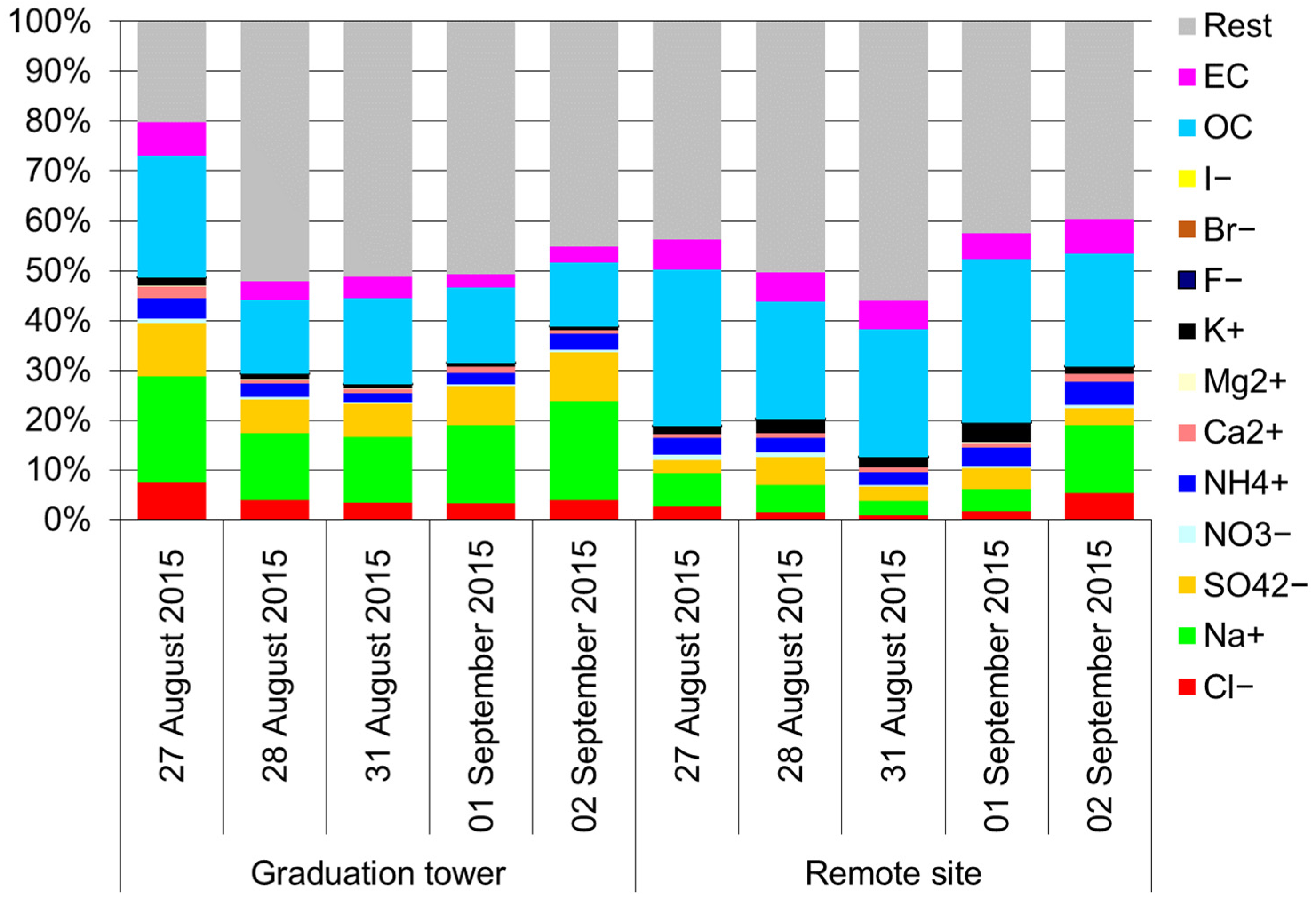

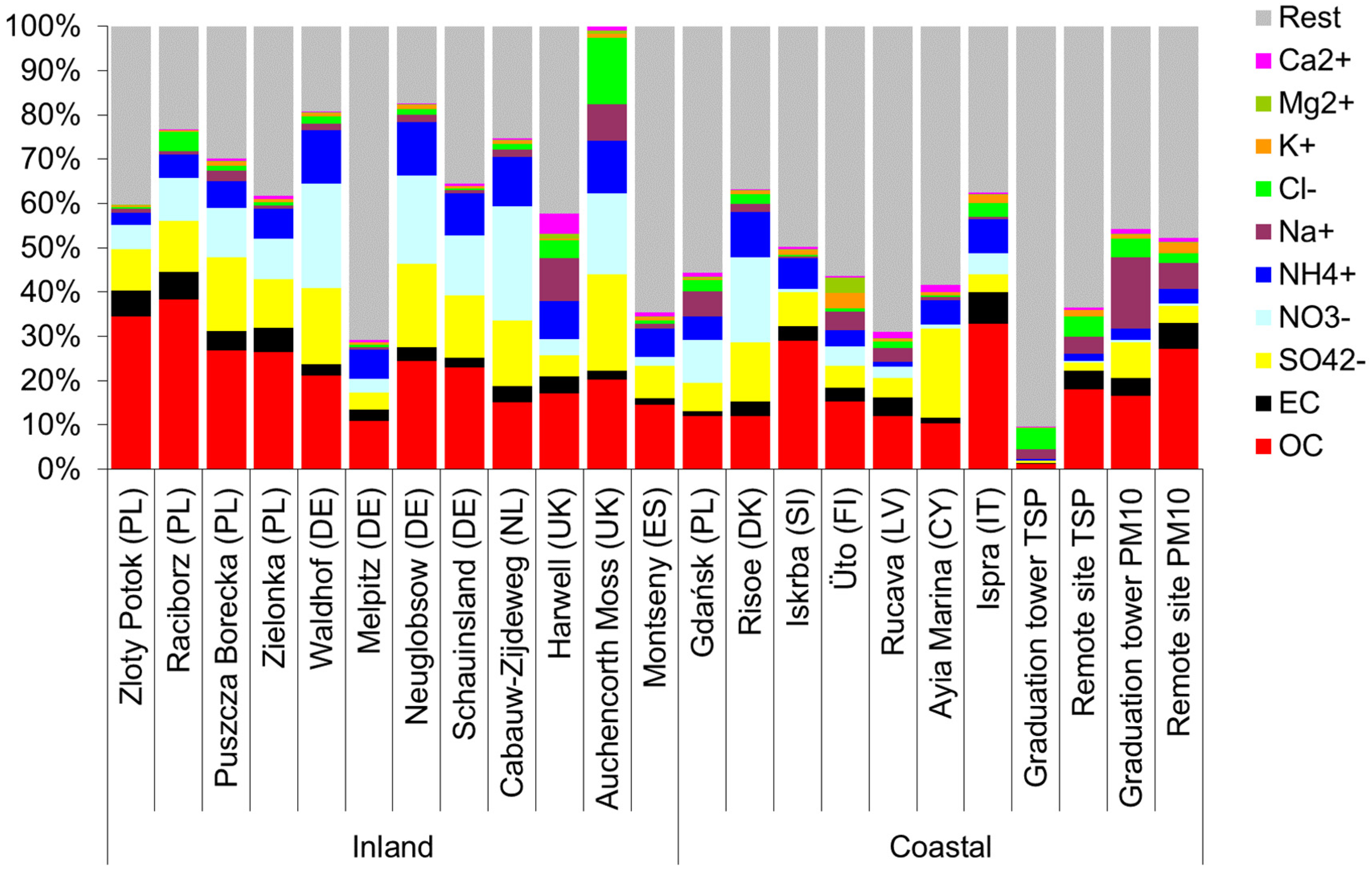

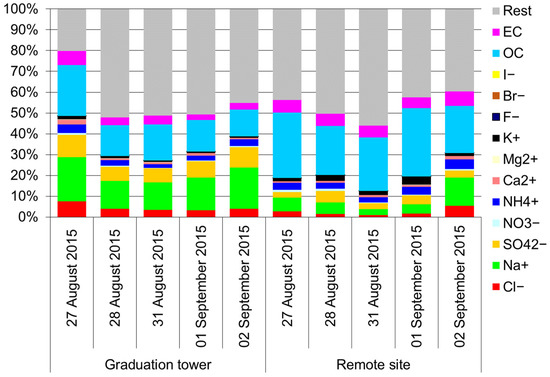

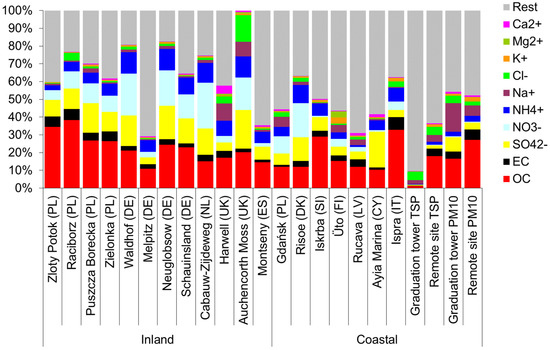

Furthermore, inside the graduation tower, the selected components largely define the mass of the PM10 aerosol (Figure 3). There is a clear difference between the chemical composition of PM10 inside and outside the graduation tower. In the graduation tower, up to 40% of the PM10 mass is made of chlorides, sodium and sulphates; sodium and chloride alone account for no less than 20% of the weight of PM10 (Figure 3). Apart from the graduation tower, the proportion of these components in the PM10 mass is much lower, and the composition of the PM10 aerosol is dominated by carbon compounds. However, it is worth noting that the composition of PM10 in the remote site is completely different from that usually observed in typical inland locations. Rather, it is similar to the composition of an aerosol in coastal zones (Figure 4) [49]. It seems that regardless of the differences between the chemical composition of PM10 at both measuring points, the brine graduation tower noticeably affects the quality and chemical composition of the air in the health resort. Most likely, the increased proportion of sodium chloride in the air, which strongly absorbs various pollutants, may affect the purification of this air from various hazardous substances, mainly volatile organic compounds (hydrocarbons). Therefore, the scope and scale of the influence of graduation towers are difficult to determine in the described experiment; they certainly depend to a large extent on weather conditions (mainly on the strength of the wind), so they are fast and strongly changeable.

Figure 3.

Mass percentage of various components in the PM10 mass.

Figure 4.

Chemical composition of an aerosol in various locations (inland and in coastal zones) [49] and in the Wieliczka Salt Mine (last four columns: grad. tower TSP, remote site TSP, grad. tower PM10; remote site PM10).

The described impact of the graduation towers on air quality, apart from its immediate surroundings, is also visible in the case of the chemical composition of TSP (Figure 2). A clear share of chlorides and sodium and a very small share of carbon compounds and nitrates in TSP clearly distinguishes the aerosol in the salt mine from a typical urban aerosol in the southern part of Poland [40,47,48,49]. The determined components of TSP in the graduation tower constituted a very small part of its mass; on average, about 10% during the research period. Chlorides and sodium make up most of these components. Since the mass fraction of various dissolved salts in brine usually does not exceed a few percent of the mass of the brine, it seems that the average fraction of the determined components in TSP, in view of the practically imperceptible share of carbon compounds in this aerosol, may be determined to a certain (slightly) degree, apart from the brine salt, by the composition of the outside air. As can be observed, apart from the influence of the graduation tower, at the Daniłowicz shaft, the aerosol also contains certain amounts of various ions, so the air migrating to the graduation tower additionally enriches the air inside the graduation tower with ions, and in various types of salts composed of the ions. The rest of TSP inside the graduation towers is water.

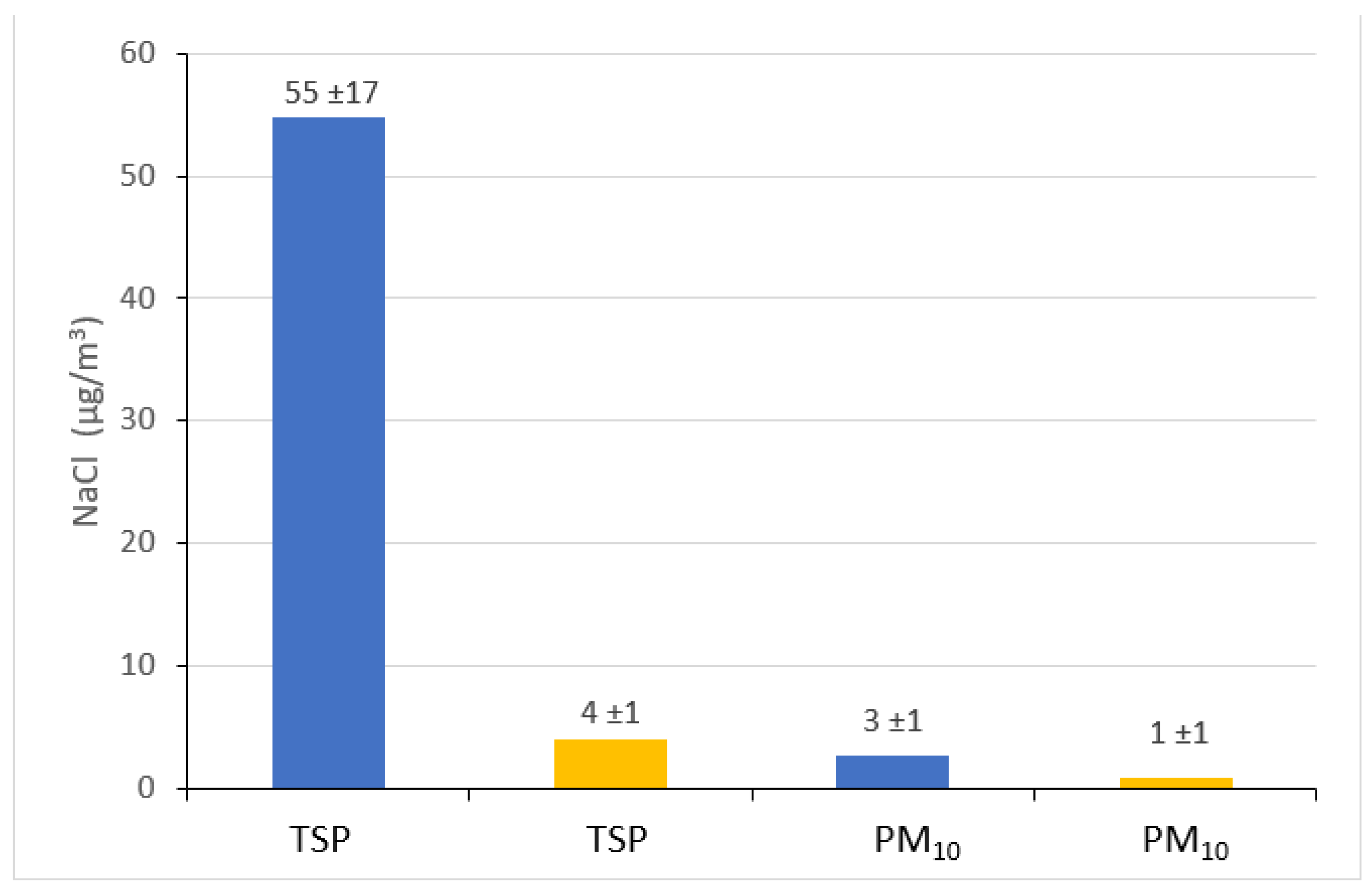

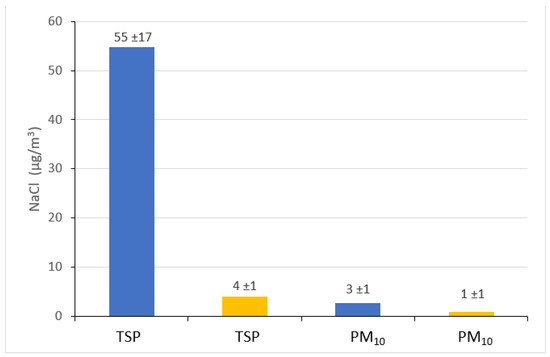

Figure 5 shows the stoichiometric estimated concentrations of sodium chloride in the air at two measurement points. It is clearly visible that they can be up to 15 times higher in the brine graduation tower (in the case of TSP on 19 August 2015) than outside the graduation tower. However, it is worth remembering that the concentrations of NaCl estimated outside the graduation tower, i.e., at the point located at the Daniłowicz shaft, are very high in relation to the concentrations recorded in typical inland areas. Therefore, it seems that the presence of such a strong source of NaCl as a graduation tower causes a change in the chemical characteristics of the aerosol over a much larger area than just the area directly adjacent to it. Another explanation for the presence of very high concentrations of NaCl outside the graduation tower could be the large NaCl contamination of roads, roadsides and soil in the area of the remote site point, which (especially in summer) can often be excluded. In the case of NaCl associated with the PM10 fraction, the concentrations in the air are several times higher in the graduation tower than outside it and, similar to the NaCl in TSP, the NaCl concentrations in PM10 in the area outside the graduation tower are surprisingly high. As in this case it concerns very fine particles, which are easily transported in the air, there is speculation that the brine graduation tower creates a specific microclimate not only inside the facility itself, but also, in a noticeable and positive way, determines the quality and chemical composition of the air in its vicinity, even several hundred meters away.

Figure 5.

Average concentrations (±standard deviations) of sodium chloride (NaCl) associated with TSP and PM10 in graduation tower site (blue columns) and in the remote site (yellow columns), estimated on the basis of stoichiometric relationships.

4. Conclusions

The results of the described investigation are the first results that were obtained using the presented methodology adapted for the purpose of carrying out research in brine graduation towers. They allow the following conclusions to be drawn:

- Inside the graduation tower, TSP concentrations are very high (the average TSP aerosol concentration in the measurement period was 994 µg/m3). Concurrent measurements of the concentration at the remote point were, on average, 18 times lower (the average concentration in the measurement period was 54 µg/m3).

- PM10 concentrations measured in the analogous configuration of the measurement points were also higher within the graduation tower (38 µg/m3 on average during the measurement period) compared to the remote site point (25 µg/m3), but the ratio of these values, in contrast to TSP, did not exceed values of 1.5.

- There was a clear difference between the chemical composition of the aerosol inside the brine graduation tower and outside the graduation tower area. In the graduation tower, 40% of the PM10 mass included chlorides, sodium and sulphates, while sodium and chloride alone constituted no less than 20% of the PM10 mass. Apart from the graduation tower, the proportion of these components in the PM10 mass was much lower, and the composition of the PM10 aerosol was dominated by carbon compounds.

- The components of TSP in the graduation tower constituted a relatively small part of its mass (during the research period, it was on average about 10%), as most of the masses of these components were made up of chlorides and sodium. Nevertheless, it should be noted that their concentrations in the air are still 1–2 orders of magnitude higher compared to the content of ions in the aerosol outside the graduation tower.

- The aerosanitary conditions in the zone of influence of the salt graduation tower of the Wieliczka Salt Mine are favorable due to the ionic composition and aerosol concentration. It is one of the important factors that determines the healing properties of the health resort. The brine graduation tower creates a specific climate, similar to a coastal microclimate, not only inside the facility itself, but also, in a noticeable and positive way, determines the quality and chemical composition of the air in its vicinity, even several hundred meters away.

- The obtained results should be treated as preliminary results, and they should be verified by further measurements and tests. It is recommended to carry out another measurement campaign that covers at least one month of aerosol sampling and that is carried out separately in two measurement seasons—summer and winter. This will be dictated by both the variability in meteorological conditions, which may affect the observed measurement results, and the different content and chemical composition of atmospheric pollutants, which is related to emissions from the communal and living sector (households and local heating devices, boiler houses and heating plants). The proposed extended measurements should be carried out in such a way that it will be possible to relate the measurement results from the brine graduation tower to at least two or three other points (the so-called remote site), located in different distances and directions from the graduation tower.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, W.R.-K., A.B., P.R.-K. and M.K.; methodology, W.R.-K., P.R.-K. and B.M.; software, B.M. and M.M.-Ł.; validation, M.R., M.M.-Ł. and A.B.; formal analysis, M.K. and A.B.; investigation, W.R.-K., A.B., P.R.-K., M.K. and B.M.; writing—original draft preparation, W.R.-K., M.R. and M.M.-Ł.; writing—review and editing, M.R., A.B., P.R.-K., M.K. and B.M.; visualization, W.R.-K., M.R. and M.M.-Ł.; project administration, M.K. and A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors of the study would like to thank the management of the Wieliczka Salt Mine for enabling the research and use of the results.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Langer, P. Salt treatment as an impulse for industrial towns’ function change. Tech. Trans. Archit. 2014, 4-A, 73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlikowska-Piechotka, A.; Piechotka, M. Revitalisation of public space to enhance spa attractiveness for tourists and residents. Archit. Civ. Eng. Environ. 2014, 3, 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Cordes, J.C.; Arnold, W.; Zeibig, B. Hydrotherapie, Elektrotherapie, Massage, 1st ed.; Steinkopff Verlag GmbH & Co. KG: Darmstadt, Germany, 1989; 978p. [Google Scholar]

- Burkowska-But, A.; Kalwasińska, A.; Brzezinska, M. The role of open-air inhalatoria in the air quality improvement in spa towns. Int. J. Occup. Environ. Health 2014, 27, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scharf, R. Die Saline Nauheim, Magistrat der Stadt Bad Nauheim. 2007, p. 19. Available online: https://es.xn--modifiwiki-g7a.vn/es/Torre_de_graduaci%C3%B3n (accessed on 19 September 2022).

- Graduation Tower. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Graduation_tower (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Drobnik, M.; Latour, T.; Sziwa, D. Strefa okołotężniowa jako inhalatorium na otwartej przestrzeni. Acta Balneol. 2018, 2, 129–133. [Google Scholar]

- Czarnobilski, K.; Szlęk, R.; Lis, G.; Obtułowicz, K.; Czarnobilska, E.; Lalik, B. The efficacy of subterraneotherapy in the treatment of bronchial asthma evaluated by nitric oxide ENO. Alergol. Immunol. 2013, 10, 30–32. [Google Scholar]

- Frączek, K.; Górny, R.L.; Ropek, D. Bioaerosols of subterraneotherapy chambers at salt mine. Aerobiologia 2013, 29, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalinowska, A.K.; Mirska, A.; Dmitruk, E. Subterraneoterapia jako swoista metoda klimatoterapii. Acta Balneol. 2013, 131, 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, T. Obiekty Subterraneoterapii w Polsce; Instytut Medycyny Uzdrowiskowej, Biblioteka Lekarza Uzdrowiskowego: Poznań, Poland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Myszkowska, D.; Kostrzon, M.; Obtułowicz, K.; Dyga, W.; Czarnobilska, E. Porównanie składu bioaerozolu w powietrzu komór solnych Uzdrowiska Kopalni Soli “Wieliczka” oraz w atmosferze w Krakowie. Acta Balneol. 2013, 133, 230. [Google Scholar]

- Nurov, I. Immunologic features of speleotherapy in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J. Health Sci. Med. 2010, 2, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bralewska, K.; Rogula-Kozłowska, W.; Mucha, D.; Badyda, A.J.; Kostrzon, M.; Bralewski, A.; Biegugnis, S. Properties of Particulate Matter in the Air of the Wieliczka Salt Mine and Related Health Benefits for Tourists. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 9, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obtułowicz, K.; Myszkowska, D.; Dyga, W.; Mazur, M.; Czarnobilska, E. Hypoalergenowa subterraneoterapia w komorach solnych Kopalni w Wieliczce w leczeniu alergii dróg oddechowych i skóry. Znaczenie bioaerozolu. Alergol. Immunol. 2013, 10, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Obtułowicz, K. Aerozole Kopalniane. [w:] Modelowe Studium Wykorzystania i Ochrony Surowców Balneologicznych Krakowa i Okolicy; IGSMiE PAN: Kraków, Poland, 2002; pp. 34–47. [Google Scholar]

- Obtułowicz, K. Mechanism of therapeutic effects of subterraneotherapy in the chambers of the Salt Mine Wieliczka. Alergol. Immunol. 2013, 10, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kostrzon, M.; Czarnobilski, K.; Badyda, A. Climate characteristics of salt chambers used for therapeutic purposes in the ‘Wieliczka’ Salt Mine. Acta Balneol. 2015, 57, 52–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gaweł, J.; Kuczaj, P. W cieniu tężni, artykuły informacyjne. Wszechświat 2012, 113, 4–6. [Google Scholar]

- Faracik, R. Tężnie w Polsce. Geneza, stan i przyszłość zjawiska Graduation towers in Poland. Genesis, current state and future of the phenomenon. Pr. Geogr. 2020, 161, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ciechocinek_graduation_towers (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Chudzińska, A.; Dybczyńska-Bułyszko, A. Brine graduation towers -a modern take on tradition. In Defining the Architectural Space—Tradition and Modernity in Architecture, 1st ed.; Wrocławskie Wydawnictwo Oświatowe: Wrocław, Poland, 2019; Volume 2, p. 31. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://podroze.onet.pl/polska/podkarpackie/kaskady-solankowe-w-solonce-k-rzeszowa-zawartosc-jodu-wyzsza-niz-w-tezniach (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- Directive 2008/50/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 May 2008 on Ambient Air Quality and Cleaner Air for Europe. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/en/ALL/?uri=CELEX%3A32008L0050 (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- US EPA. National Ambient Air Quality Standards for Particulate Matter; Final Rule; 40 CFR Part 50; Federal Register; 25; US EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 1997; Volume 62.

- US EPA. Compendium of Methods for the Determination of Toxic Organic Compounds in Ambient Air, 2nd ed.; Compendium Method TO-13A; Determination of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Ambient Air Using Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS); Center for Environmental Research Information Office of Research and Development, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1999.

- US EPA. Policy Assessment for the Review of the Particulate Matter National Ambient Air Quality Standards; US EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2009.

- PN-EN 12341:2006a; Air Quality—Determination of the PM10 Fraction of Suspended Particulate Matter—Reference Method and Field Test Procedure to Demonstrate Reference Equivalence of Measurement Methods. European Standards: Pilsen, Czech Republic, 2006.

- PN-EN 14907:2006b; Ambient Air Quality—Standard Gravimetric Measurement Method for the Determination of the PM2.5 Mass Fraction of Suspended Particulate Matter. European Standards: Pilsen, Czech Republic, 2006.

- Khlystov, A.; Lin, M.; Bolch, M.A.; Ma, Y. Investigation of the positive artifact formation during sampling semi-volatile aerosol using wet denuders. Atmos. Environ. 2009, 43, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, S.; Biswas, P. Sampling artifacts in denuders during phase partitioning measurements of semi-volatile organic compounds. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalli, F.; Viana, M.; Yttri, K.E.; Genberg, J.; Putaud, J.P. Toward a standardized thermal-optical protocol for measuring atmospheric organic and elemental carbon: The EUSAAR protocol. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2010, 3, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błaszczak, B.; Mathews, B. Characteristics of Carbonaceous Matter in Aerosol from Selected Urban and Rural Areas of Southern Poland. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogula-Kozłowska, W. Size-segregated urban particulate matter: Mass closure, chemical composition, and primary and secondary matter content. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2016, 9, 533–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://powietrze.gios.gov.pl/pjp/current?woj=malopolskie&rwms=true (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Tobler, A.K.; Skiba, A.; Canonaco, F.; Močnik, G.; Rai, P.; Chen, G.; Bartyzel, J.; Zimnoch, M.; Styszko, K.; Nęcki, J.; et al. Characterization of non-refractory (NR) PM1 and source apportionment of organic aerosol in Kraków, Poland. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2021, 21, 14893–14906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samek, L.; Stegowski, Z.; Furman, L.; Styszko, K.; Szramowiat, K.; Fiedor, J. Quantitative Assessment of PM2.5 Sources and Their Seasonal Variation in Krakow. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2017, 228, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, P.; Styszko, K.; Skiba, A.; Zięba, Z.; Zimnoch, M.; Kistler, M.; Kasper-Giebl, A.; Gilardoni, S. Seasonal Variability of PM10 Chemical Composition Including 1,3,5-triphenylbenzene, Marker of Plastic Combustion and Toxicity in Wadowice, South Poland. Air Pollut. Health Eff. 2021, 21, 200223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogula-Kozłowska, W.; Klejnowski, K.; Rogula-Kopiec, P.; Ośródka, L.; Krajny, E.; Błaszczak, B.; Mathews, B. Spatial and seasonal variability of the mass concentration and chemical composition of PM2.5 in Poland. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 2014, 7, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: www.gios.gov.pl (accessed on 12 February 2022).

- Niekurzak, M. The Potential of Using Renewable Energy Sources in Poland Taking into Account the Economic and Ecological Conditions. Energies 2021, 14, 7525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauers, H.; Oei, P.-Y. The political economy of coal in Poland: Drivers and barriers for a shift away from fossil fuels. Energy Policy 2020, 144, 111621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Poland 2022. Energy Policy Review; On-Line Report; IEA: Paris, France, 2022; p. 177.

- Kostrzon, M.; Latour, T.; Badyda, A.J.; Rogula-Kozłowska, W.; Leśny, M. Badania składu chemicznego aerozolu w Uzdrowisku Kopalnia Soli “Wieliczka” metodą “płuczkową”. Pol. Stow. Górnictwa Solnego 2017, 13, 107–114. [Google Scholar]

- Rogula-Kozłowska, W.; Kostrzon, M.; Rogula-Kopiec, P.; Badyda, A.J. Particulate Matter in the Air of the Underground Chamber Complex of the Wieliczka Salt Mine Health Resort. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 955, 9–18. [Google Scholar]

- Rogula-Kozłowska, W. Traffic-generated changes in the chemical characteristics of size-segregated urban aerosols. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2014, 93, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogula-Kozłowska, W. Chemical composition and mass closure of ambient particulate matter at a crossroads and a highway in Katowice, Poland. Environ. Prot. Eng. 2015, 41, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogula-Kozłowska, W.; Klejnowski, K.; Rogula-Kopiec, P.; Mathews, B.; Szopa, S. A Study on the Seasonal Mass Closure of Ambient Fine and Coarse Dusts in Zabrze, Poland. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2012, 88, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: http://www.eea.europa.eu/data-and-maps/data/airbase-the-european-air-quality-database-7 (accessed on 12 February 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).