Towards A Situated Urban Political Ecology Analysis of Packaged Drinking Water Supply

Abstract

:1. Introduction: The Growth of Packaged Drinking Water Supply

2. Situating Explanations of PDW Supply

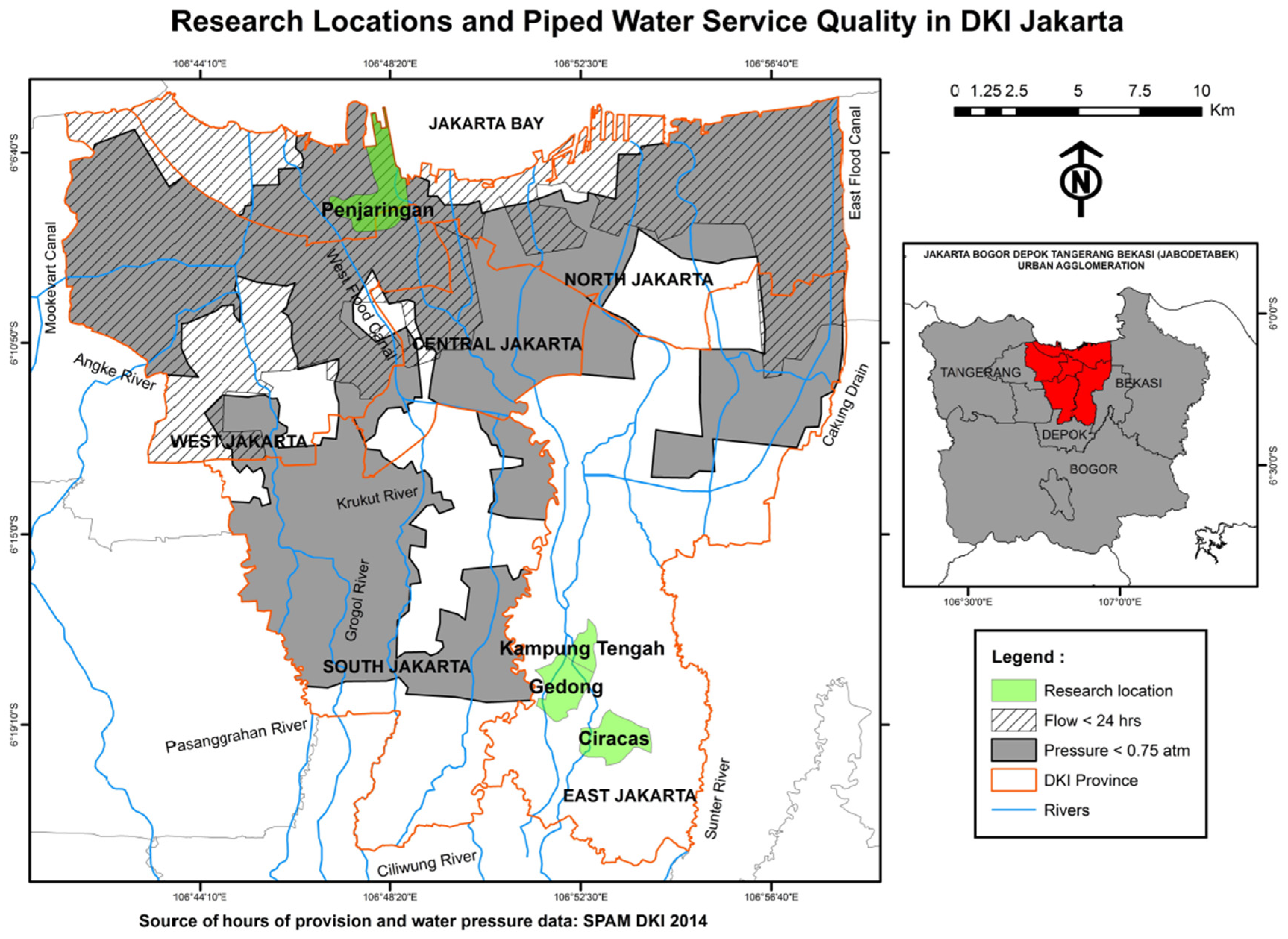

3. Research Design

4. Understanding PDW Supply in Low Income Neighborhoods of Jakarta

4.1. Practices of Household Water Supply

4.2. Explaining PDW Supply in Indonesia through an Analysis of the Individual

“We haven’t paid a lot of attention to refill water. That is because in Indonesia, households have more than one water source, so we focus on the domestic use. And if the households choose to fulfill their drinking water need through drinking refill water that’s a choice, as long as they have enough water supply through an improved source. And, for Jakarta, this is mostly piped water.”

“At the moment in Indonesia it is more important to expand access for the people, so people at least have improved water and sanitation services. Whether it has to be potable or not… I think that’s the second layer of priority.”

4.3. Towards the Politics of PDW Consumption: Societal Processes and Social Relations

4.3.1. Inequalities within Access to Improved Piped Water Domestic Sources

4.3.2. Inequalities within Access to Improved Groundwater Sources

5. Discussion: More than Temporary Inequalities

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Badan Pusat Statistik. Household by Region and Primary Source of Drinking Water. 2010. Available online: http://sp2010.bps.go.id/index.php/site/tabel?search-tabel=Household+by+Region+and+Primary+Source+of+Drinking+Water&tid=303&search-wilayah=DKI+Jakarta+Province&wid=3100000000&lang=en (accessed on 13 January 2018).

- Badan Pusat Statistik. Statistik Indonesia 2017. [Statistical Yearbook of Indonesia]; 2017. Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/publication/2017/07/26/b598fa587f5112432533a656/statistik-indonesia-2017 (accessed on 27 November 2017).

- Dewi, N.K. Analysis: Bottled Water Industry Faces Both Growth and Challenges. The Jakarta Post. Available online: http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2015/05/27/analysis-bottled-water-industry-faces-both-groth-and-challenges.html (accessed on 31 October 2018).

- World Bank. More and Better Spending: Connecting People to Improved Water Supply and Sanitation in Indonesia—Water Supply and Sanitation Public Expenditure Review (WSS-PER); Water and Sanitation Program, World Bank: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rodwan, J.G., Jr. Bottled Water 2015: U.S. and International Development and Statistics. International Bottled Water Association, July–August 2016. Available online: http://www.bottledwater.org/public/BWR_Jul-Aug_2016_BMC%202015%20bottled%20water%20stat%20article.pdf#overlay-context=economics/industry-statistics (accessed on 6 August 2017).

- Clarke, T. Inside the Bottle: Exposing the Bottled Water Industry; Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, G.; Potter, E.; Race, K. Plastic Water: The Social and Material Life of Bottled Water; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opel, A. Constructing Purity: Bottled water and the commodification of nature. J. Am. Cult. 1999, 22, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Race, K. ‘Frequent sipping’: Bottled water, the will to health and the subject of hydration. Body Soc. 2012, 18, 72–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Bhaduri, S. Consumption conundrum of bottled water in India: An STS perspective. Bull. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2014, 33, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bain, R.; Cronk, R.; Wright, J.; Yang, H.; Slaymaker, T.; Bartram, J. Fecal contamination of drinking-water in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014, 11, e1001644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoler, J. From curiosity to commodity: A review of the evolution of sachet drinking water in West Africa. WIREs Water 2017, 4, e1206. [Google Scholar]

- Stoler, J. Improved but unsustainable: Accounting for sachet water in post-2015 goals for global safe water. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2012, 17, 1506–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, K.; Kooy, M. Worlding water supply: Thinking beyond the network in Jakarta. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2017, 41, 888–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaglin, S. Être branché ou pas: Les entre-deux des villes du sud [Being connected or not: The in-between of the cities of the South]. Flux 2004, 2, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawhon, M.; Ernstson, H.; Silver, J. Provincializing urban political ecology: Towards a situated UPE through African urbanism. Antipode 2014, 46, 497–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooy, M. Developing informality: The production of Jakarta’s urban waterscape. Water Alternatives 2014, 7, 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Kooy, M.; Bakker, K. Technologies of government: Constituting subjectivities, spaces and infrastructures in colonial and contemporary Jakarta. Inter. J. Urban Regional Res. 2008, 32, 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooy, M.; Walter, C.T.; Prabaharyaka, I. Inclusive development of urban water services in Jakarta: The role of groundwater. Habitat Int. 2018, 73, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Francisco, J.P.S. Why households buy bottled water: A survey of household perceptions in the Philippines. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeradisastra, F. Prospek dan Tren Industri Minuman Ringan Indonesia Memasuki 2012: Urbanisasi dan Kemakmuran? Available online: http://foodreview.co.id/blog-56483-Prospek-dan-Perkembangan-Industri-Minuman-Ringan-di-Indonesia.html (accessed on 16 September 2018).

- Massoud, M.A.; Maroun, R.; Abdelnabi, H.; Jamali, I.I.; El-Fadel, M. Public perception and economic implications of bottled water consumption in underprivileged urban areas. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2013, 185, 3093–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rani, B.; Maheshwari, R.; Garg, A.; Prasad, M. Bottled water—A global market overview. Bull. Environ. Pharmacol. Life Sci. 2012, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, J. Bottled water in Mexico: The rise of a new access to water paradigm. WIRES Water. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Safely Managed Drinking Water—Thematic Report on Drinking Water 2017; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Prasetiawan, T.; Nastiti, A.; Muntalif, B.S. ‘Bad’ piped water and other perceptual drivers of bottled water consumption in Indonesia. WIREs Water 2017, e1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, G. The impacts of bottled water: An analysis of bottled water markets and their interactions with tap water provision. WIREs Water 2017, 4, e1203. [Google Scholar]

- Brei, V.A. How is a bottled water market created? Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2018, 5, e1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, H.; Wright, A. Still Sparkling: The Phenomenon of Bottled Water—An Irish Context. J. Mark. Manag. 2014, 2, 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Viscusi, W.K.; Huber, J.; Bell, J. The private rationality of bottled water drinking. Contemp. Econ. Policy 2015, 33, 450–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilk, R. Bottled Water: The pure Commodity in the age of branding. J. Consum. Cult. 2006, 6, 303–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, C.T.; Kooy, M.; Prabaharyaka, I. The role of bottled drinking water in achieving SDG 6.1: An analysis of affordability and equity from Jakarta, Indonesia. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 2017, 7, 642–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nastiti, A.; Muntalif, B.S.; Roosmini, D.; Sudradjat, A.; Meijerink, S.V.; Smits, A.J.M. Coping with poor water supply in peri-urban Bandung, Indonesia: Towards a framework for understanding risks and aversion behaviours. Environ. Urban. 2017, 29, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoler, J.; Tutu, R.A.; Winslow, K. Piped water flows but sachet consumption grows: The paradoxical drinking water landscape of an urban slum in Ashaiman, Ghana. Habitat Int. 2015, 47, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roekmi, R.A. Safe Water at a Premium. Inside Indonesia. 16 January. Available online: http://www.insideindonesia.org/safe-water-at-a-premium (accessed on 31 October 2017).

- Williams, A.R.; Bain, R.E.; Fisher, M.B.; Cronk, R.; Kelly, E.R.; Bartram, J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of fecal contamination and inadequate treatment of packaged water. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sima, L.C.; Desai, M.M.; McCarty, K.M.; Elimelech, M. Relationship between use of water from community-scale water treatment refill kiosks and childhood diarrhea in Jakarta. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2012, 87, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quansah, F.; Okoe, A.; Angenu, B. Factors affecting Ghanaian consumers’ purchasing decision of bottles water. Int. J. Market Stud. 2015, 7, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alda-Vidal, C.; Kooy, M.; Rusca, M. Mapping operation and maintenance: An everyday urbanism analysis of inequalities within piped water supply in Lilongwe, Malawi. Urban Geogr. 2018, 39, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusca, M.; Boakye-Ansah, A.S.; Loftus, A.; Ferrero, G.; van der Zaag, P. An interdisciplinary political ecology of drinking water quality. Exploring socio-ecological inequalities in Lilongwe’s water supply network. Geoforum 2017, 84, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morinville, C. Sachet water: Regulation and implications for access and equity in Accra, Ghana. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Water 2017, 4, e1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsterdam Institute for Social Science Research. AISSR Ethical Review Procedure and Questions. Available online: http://aissr.uva.nl/binaries/content/assets/subsites/amsterdam-institute-for-social-science-research/map-1/aissr-ethical-review-procedure-and-questions.pdf?1487234676823 (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- Badan Pusat Statistik. Average Household Size by Province, 2000–2015. 2017. Available online: https://www.bps.go.id/linkTableDinamis/view/id/849 (accessed on 27 November 2017).

- Deny, S. Tuntut UMP Rp 3,8 Juta Di 2017, Begini Hitungan Buruh. Liputan 6. Available online: http://bisnis.liputan6.com/read/2622371/tuntut-ump-rp-38-juta-di-2017-begini-hitungan-buruh (accessed on 31 October 2018).

- Fatmawati, V. IUWASH Water Cost Survey: Field Note. Indonesia Urban Water, Sanitation & Hygiene. News. IUWASH Newsl. 2013, 4, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Noordegraaf, A. Improving access to clean water by low-income urban communities in Jakarta, Indonesia. Master’s Thesis, Department of Geography, Planning and International Development, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Badan Regulator Penyediaan Air Minum. Evaluasi Kinerja Pelayanan air Minum Tahun 2014 [Evaluation of the Performance of the Service of Drinking Water by 2014]; Badan Regulator Penyediaan Air Minum: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nganyanyuka, K.; Martinez, J.; Wesselink, A.; Lungo, J.H.; Georgiadou, Y. Accessing water services in Dar es Salaam: Are we counting what counts? Habitat Int. 2014, 44, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deltares. NCICD: Water Supply Jakarta; Unpublished Document Presented at National Capital Integrated Coastal Development (NCICD) Knowledge Stakeholder Open Workshop; Indonesian Ministry of Public Works: Jkarta, Indonesia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zamzami, I.; Ardhanie, N. An End to the Struggle? Jakarta Residents Reclaim Their Water System. In In Our Public Water Future. The Global Experience with Remunicipalisation; Kishimoto, S., Lobina, E., Petitjean, O., Eds.; Transnational Institute: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Available online: http://www.municipalservicesproject.org/sites/municipalservicesproject.org/files/publications/Kishimoto-Lobina-Petitjean_Our-Public-Water-Future-Global-Experience-Remunicipalisation_April2015_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2016).

- Bakker, K.; Kooy, M.; Shofiani, N.E.; Martijn, E.J. Governance failure: Rethinking the institutional dimensions of urban water supply to poor households. World Dev. 2008, 36, 1891–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Detik. 45% Air Tanah Jakarta Tercemar E-coli [45% of Groundwater in Jakarta Contaminated with E-coli]. Detik. Available online: http://news.detik.com/berita/2411711/45-persen-air-tanah-jakarta-tercemar-bakteri-e-coli (accessed on 13 November 2014).

- Prabowo, D.S. 90 Persen Air Tanah Jakarta Mengandung Bakteri E-coli [90 Percent of Jakarta’s Groundwater Contains E-coli Bacteria]. Tribunnews. 2011. Available online: http://www.tribunnews.com/metropolitan/2011/06/07/90-persen-air-tanah-jakarta-mengandung-bakteri-e-coli (accessed on 31 October 2018).

- Deltares. Annex A, B & C: Sinking Jakarta: Annex A, B &C, Causes & Remedies; Unpublished Project Report; Deltares: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, M.; Nastiti, A.; Muntalif, B.S. Improved but not always safe: A microbial water quality analysis in Bandung peri-urban households. Presented at the 5th Environmental Technology and Management Conference: Green Technology towards Sustainable Environment, Bandung, Indonesia, 23–24 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Augustinus, R.B. Understanding the Implementation of Groundwater Regulations and Policies for the Commercial Deep Well Users in Jakarta, Indonesia. Master’s Thesis, UNESCO-IHE Institute of Water Education, Delft, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Average Household Income * | Share of Households below poverty Line ** | Share of Households Consuming PDW ** | Average Household Income * | Share of Households below poverty Line ** | Share of Households Consuming PDW ** | Average Household Income * | Share of Households below poverty Line ** | Share of Households Consuming PDW * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey A | Penjaringan | Gedong and Ciracas | Total | ||||||

| 4.77 (352.03) | 50.58 | 82.35 | 5.17 (381.55) | 50.96 | 76.92 | 4.99 (368.26) | 50.79 | 79.37 | |

| Survey B | Penjaringan | Gedong and Kampung Tengah | Total | ||||||

| 3.69 (272.32) | 67.50 | 100 | 4.13 (304.79) | 57.50 | 100 | 3.90 (287.82) | 62.50 | 100 | |

| Penjaringan | Gedong and Ciracas (A)/Kampung Tengah (B) | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a) PDW USE: TYPE (SURVEY A) * | |||||||

| Refill PDW only | 14.12 | 23.08 | 19.04 | ||||

| Branded PDW only | 64.71 | 47.12 | 55.02 | ||||

| Combination refill/branded | 3.53 | 6.73 | 5.29 | ||||

| Total | 82.35 | 76.92 | 79.37 | ||||

| b) PDW USE: PURPOSE (SURVEY B) * | |||||||

| Drinking only | 35 | 7.5 | 21.25 | ||||

| Home enterprise only | 5 | 0 | 2.5 | ||||

| Drinking and cooking | 45 | 67.5 | 56.25 | ||||

| Cooking and home enterprise | 0 | 5 | 2.5 | ||||

| Drinking and home enterprise | 7.5 | 0 | 3.75 | ||||

| Drinking and cooking and home enterprise | 7.5 | 20 | 13.75 | ||||

| c) PDW USE: VOLUME ** | |||||||

| Survey A | Survey B | Survey A | Survey B | Survey A | Survey B | ||

| Branded PDW | Average | 179.00 | 123.44 | 117.38 | 95.64 | 148.19 | 109.54 |

| Minimum | 19.00 | 50.40 | 19.00 | 30.00 | 19.00 | 30.00 | |

| Maximum | 608.00 | 172.80 | 304.00 | 152.00 | 608.00 | 172.80 | |

| Refill PDW | Average | 131.07 | 312.36 | 231.28 | 196.84 | 181.18 | 254.60 |

| Minimum | 57.00 | 76.00 | 19.00 | 76.00 | 19.00 | 76.00 | |

| Maximum | 465.00 | 2128.00 | 570.00 | 1368.00 | 570.00 | 2128.00 | |

| Source | Penjaringan | Gedong and Ciracas | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Piped water | 10.59 | 3.85 | 6.88 |

| Piped water + branded PDW | 37.65 | 19.23 | 27.51 |

| Piped water + refill PDW | 4.71 | 15.38 | 10.58 |

| Piped water + branded PDW + refill PDW | 2.35 | 5.77 | 4.23 |

| Piped water (total) | 55.29 | 44.23 | 49.21 |

| Nyelang water | 7.06 | 0 | 3.17 |

| Nyelang water + branded PDW | 27.06 | 0 | 12.17 |

| Nyelang water + refill PDW | 9.41 | 0 | 4.23 |

| Nyelang water + branded PDW + refill PDW | 1.18 | 0 | .52 |

| Nyelang (total) | 44.71 | 0 | 20.11 |

| Piped water (direct + indirect) | 100 | 44.23 | 69.31 |

| Groundwater | 0 | 18.27 | 10.05 |

| Groundwater + branded PDW | 0 | 26.92 | 14.81 |

| Groundwater + refill PDW | 0 | 7.69 | 4.23 |

| Groundwater + branded PDW + refill PDW | 0 | 0.96 | 0.52 |

| Groundwater (total) | 0 | 53.85 | 29.63 |

| Piped water + groundwater | 0 | 0.96 | 0.52 |

| Piped water + groundwater + branded PDW | 0 | 0.96 | 0.52 |

| Source | Penjaringan | Gedong and Ciracas | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Groundwater | 0 | 46.25 | 24.67 |

| Piped water (direct) | 54.29 | 52.5 | 53.34 |

| Piped water (indirect) | 45.71 | 0 | 21.34 |

| Groundwater + piped water (direct) | 0 | 1.25 | 0.67 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kooy, M.; Walter, C.T. Towards A Situated Urban Political Ecology Analysis of Packaged Drinking Water Supply. Water 2019, 11, 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11020225

Kooy M, Walter CT. Towards A Situated Urban Political Ecology Analysis of Packaged Drinking Water Supply. Water. 2019; 11(2):225. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11020225

Chicago/Turabian StyleKooy, Michelle, and Carolin T. Walter. 2019. "Towards A Situated Urban Political Ecology Analysis of Packaged Drinking Water Supply" Water 11, no. 2: 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11020225

APA StyleKooy, M., & Walter, C. T. (2019). Towards A Situated Urban Political Ecology Analysis of Packaged Drinking Water Supply. Water, 11(2), 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11020225