Abstract

Poor access to municipal water in Ahmedabad’s Muslim areas has been tied to the difficulties of implementing a planning mechanism called the town planning scheme, which, in turn, have been premised on widespread illegal constructions that have developed across these sites. Residents, local politicians, and activists associate this causal explanation offered by engineers and planners for poor water access with a deliberate state-led intent to discriminate against them on the basis of religion. Using this causal association as a methodological entry-point, I examine through this paper how religious difference mediates decision-making and outcomes embodied by technical plans. Demonstrating how the uneven implementation of plans is not always a state-driven exercise as is often imagined, but instead a culmination of intense mediations between influential state and non-state actors with varying interests, I offer the following insights on water governance for sites divided by religion: (a) Negotiations driven by discourses on religious difference are a powerful force influencing the formulation of plans facilitating water access. However, these negotiations and plans are, simultaneously, also vulnerable to other political, legal, and economic pressures. Water governance across such sites thus often unfolds in an unstable landscape of unmapping and mapping; (b) influential legal actors from both majority and minority communities exert pressures obstructing the formulation and implementation of technical plans. The production of observable unmapped water access in minority areas thus, in reality, might not be contained within neat divides such as religion or illegality, but instead be a culmination of shifting interests, contestations, and negotiations confounding such categories; (c) institutionalized planning practices implicated in the intentional production of unmapping in such contexts might instead simply be discursive categories around which uneven water access coalesces.

1. Introduction

“… The corporation has sanctioned T.P Scheme 84(B) for our area and through the implementation of this scheme, pucca (see Supplementary Materials 1) roads, street lights, and drinking water from the Narmada have been provided in a large part of the area. Despite being part of this same T.P. Scheme, only our area with Muslim population (sic) has been discriminated against by not providing us the basic services due to us through the implementation of the T.P. This is illegal and is in violation of our basic rights… We have been deprived of clean drinking water by this biased treatment. This step of the municipal corporation is inappropriate, unreasonable, illegal, and clearly unconstitutional.”- Letter by Sarkhej residents to Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation, 10 November 2015 (see Supplementary Materials 2)

“Every time we ask them to build infrastructure, they give some excuse or the other. Like the T.P. is not final yet, it is at this stage, that stage, etc… Call it our misfortune.”- Municipal Councillor, Makhtampura Ward; Interview, 5 September 2017

In September 2017, I met with a municipal councilor at the hot, dusty construction site of a new water distribution station in Ahmedabad, a city in western India, where I had been conducting research on political conflicts over municipal water distribution. In meeting him, I had hoped to understand the role of urban wards, the smallest administrative units in Indian cities, in influencing local residents’ access to municipal water. His despair captured in the second quote above—of being given “some excuse or the other” in response to demands for infrastructure—came towards the end of our conversation. By this point, he had already talked at some length about the many institutional practices, which in his view, were complicit in producing selectively poor access to basic services such as water for Ahmedabad’s Muslim areas. One such practice implicated in the production of exclusion by both quotes is the town planning scheme (or T.P. Scheme, as referred to in the first quote), a planning process followed in Ahmedabad entailing the pooling and reconstitution of land for building urban infrastructure. In contrast to the land acquisition method (employing the principle of eminent domain) widely practiced in other parts of India, the town planning scheme (TPS from here on) process is praised for being participatory, democratic, and equitable (for landowners), financially and politically strategic (for city planning agencies), and efficient at rapidly fulfilling infrastructure needs in general [1]. In Makhtampura and Sarkhej, two of Ahmedabad’s largest Muslim areas however, the TPS is held complicit in these areas being left deliberately unmapped, i.e., for the planning and building of infrastructures providing access to basic services remaining largely missing. While the opening quotes are two examples embodying such implications, the sentiment is found widely echoed in other public interest litigations and media reports, as well as by local residents, officials, and politicians. These allegations suggest that the uneven implementation of the planning process in the city’s Muslim areas is an instantiation of the state deliberately and religiously discriminating against these areas in a direct and causal way.

Critical theoretical and empirical work in contexts of observable uneven governance however has complicated the location of state-led intentionality in institutionalized planning processes. Planning in India has famously been described as “the relationship between the published plan and unmapped territory” [2] (p. 81). Urban governance here, according to Ananya Roy’s powerful formulation, operates as much through an “‘unmapping’ of cities” as it does through more widely recognized governing technologies such as “visibility, counting, mapping, and enumerating” [2] (p. 81). The suggestion that acts of “deregulation” (an intentional lack of regulation maintained by the state) and “unmapping” (deliberate planning practices of not mapping) [2] (p. 83) are central to the implementation of planning mechanisms such as land use controls, eminent domain, masterplans, and so on (see also, [3]) lends nuance to the understanding of mapping as an instantiation of political power [4] (p. 90). If mapping is to be understood as a central tool with which to govern and control territories, so should unmapping. Indeed, this conception of unmapping as a deliberate state-directed strategy of denying access seems to provide a straightforward explanation for the opening quotes above. However, more recent empirical work in Indian cities has destabilized not only the prescription of intentionality to unmapping without a closer understanding of how and why the unmapped situation came to be, but also the notion that unmapping is a state-led exercise. Lisa Björkman [5], for instance, shows how the unmapping of Mumbai’s water networks, far from being a deliberate hegemonic act of the state, was instead an inadvertent consequence of numerous technical, technological, and material planning efforts to map and govern; efforts mediated by a host of formal and informal actors. The location of state-directed intentionality within observable unmapped conditions in Indian cities, thus, remains hotly debated. How then, might the direct and causal way in which the TPS is implicated in the deliberate production of unmapping in Ahmedabad’s Muslim areas hold up against this understanding?

With governance being widely understood as processes “of decision making… structured by institutions (laws, rules, norms, and customs) and shaped by ideological preferences” [6] (p. 44) and in light of the above discussion of unmapping in relation to governance in Indian cities, how might observable unmapped access to municipal water in Ahmedabad’s Muslim areas be better understood? What insights might this case offer for water governance in cities divided by religion?

The need to ask these questions is premised in concerns around political implications of direct and causal ways of examining, understanding, and explaining environmental justice in contexts of deep socio-economic differences. Pulido [7] for instance, problematizes reductive ways of defining, identifying, and theorizing environmental racism for obscuring a deeper understanding of how race comes together with other socio-political and economic forces to constitute oppressive situations. She insists, instead, on the need to deconstruct discourses and assumptions constituting a monolithic understanding of racism in order to “move to a more meaningful and nuanced understanding of what environmental racism is, how it is produced, and how an anti-racist and left movement can develop” [7] (p. 144). This inquiry into unmapped water access in Ahmedabad’s Muslim areas is driven by similar worries. Reductive ways of associating uneven governance across these sites with state-led intentionality to discriminate on the basis of religion obscures how, in reality, religion comes together with socio-economic and political forces to constitute observable unmapped water access. This propensity, on the one hand, runs the risk of reproducing rhetoric, which is problematic in itself in reinforcing wider monolithic understandings of communities (see [8] for more on this). In relation, and on the other hand, it also allows easy explanations for cited impossibilities and inaction escape unchallenged, and thwarts possibilities of any meaningful change.

That religion and ethnicity influence the ability of communities to access housing and basic services is well recognized (see Supplementary Materials 3) [9,10,11,12,13]. Cities, as a result of their densities, networks, and the political and economic gains they stand to offer, have been noted for being predominant sites of enactment for such differential access [14] (p. 212), [10] (pp. 11–15). With visibly stark differences between urban infrastructure and housing across its Hindu and Muslim areas, the city of Ahmedabad presents itself as one such site. The spatial reproduction of Ahmedabad’s religious cleavages has, in recent years, earned the city titles such as “shock city” [15], “riot city” [16], and “communalized city” [17]. Indeed, much has been written about the Muslim marginalization that Ahmedabad has witnessed, in particular since the 2002 Hindu–Muslim riots. Some of this scholarship has focused on the violence of the riots and the displacement, resettlement, formation of “ghettos”, and persistent poor living conditions that have followed [18,19,20]. Neera Chandhoke, for instance, talks about how “in Ahmedabad, Muslim ghettos—and there is no other kind of ghetto in the city—are typed by other residents as mini-Pakistans, and the road between these sadly impoverished and denuded localities and other areas is construed as the ‘border’” [19] (p. 2). Another set of studies have located the production of a socio-spatially divided Ahmedabad with evidently under-served Muslim areas within broader city-wide processes of socio-economic and political disenfranchisement of vulnerable groups in the city [16,17,21,22,23]. All of this work points to the politics of Hindutva in the production of Ahmedabad as a city divided along religious lines and descriptively highlights the observably poor access to urban infrastructure in these areas. Less, however, is known about the micro-politics animating the processes and practices governing access to basic services in these parts of the city. Calling into question uncomplicated implications of the TPS in the production of Ahmedabad’s religiously differentiated access to municipal water supply, this is the gap I hope to fill through this paper.

Engineers, planners, and local politicians I spoke to bemoaned the inability to build roads for laying trunk infrastructure and the unavailability of plots for building water distribution stations (WDSs from here on) as the two biggest obstructions in getting municipal water to Makhtampura and Sarkhej. This impasse, in turn, is attributed to widespread illegal constructions and encroachments in these areas, which ostensibly have made it extremely difficult to plan, map, or govern these sites. According to these officials, the planning and building of infrastructures for providing basic services to many of these areas is deadlocked as a practical consequence of such illegalities. Planning neighboring Hindu areas on the other hand, presumably because of the lack of ubiquitous illegalities, is cited as being easier. As a consequence, and in contrast to the city’s Muslim areas, its Hindu parts present themselves as being significantly better networked, with water access being one site, across which differences are noted and contested.

Water access is produced through the deployment of a complex set of infrastructures that are not only physical and material things in themselves, but also constitutive of relations, desires, and promises [24]. In Mumbai for instance, Björkman [5] (p. 13) describes how “… a water distribution main laid with much pomp and show by a politician in the run-up to an election might work as much to demonstrate a political aspirant’s capacity to mobilize the apparatus of the state as it does to improve water supply to a neighbourhood”. Yet, symbolic desires cannot take physical form without putting to work a range of material, physical, and bureaucratic processes. So, on the one hand, while the intentionality behind producing water access might lie in political desires of a specific kind, on the other hand, the material and physical work of producing access unfolds through institutionalized technical procedures as well as spatio-temporally specific conditions such as legalities, regulations, already existing infrastructures, what place is upstream or downstream from another, up-network or down-network, and so on. Water infrastructures, thus, operate equally across symbolic, practical, and technical registers, with access to water being mediated by physical, material, technical, technological, bureaucratic, ideological, and political processes at multiple levels [25].

Back in Ahmedabad however, the uncomplicated implication of planning processes, such as the TPS (and the development plan, as subsequent sections illustrate), in producing unmapped water access in the city’s Muslim neighborhoods occludes a deeper understanding of how processes and relationships unfold across multiple registers to influence access. An inquiry into the physical, material, technical, technological, bureaucratic, ideological, and political processes that have produced unmapped water access at these sites remains missing. Questioning the causal explanations presented by allegations suggesting the deliberate complicity of planning processes in producing religiously unmapped water access, I use these implications instead as methodological entry points for explicating the relationships and negotiations embodied by planning propositions influencing water access across these sites. How, in the formulation and/or implementation of planning processes such as the TPS, does differentiated water access come into being? How, in relation to these processes, might the role of religion be better understood?

This essay draws on 24 months of qualitative research in Ahmedabad, between 2016 and 2018. It draws on insights from interviews and dialogues including those with residents, community organizations, NGO officials, ward councillors (politicians), municipal engineers and bureaucrats, planners, builders, formal and informal business owners, and academics as well as on legal, official, and media documents (see Supplementary Materials 4 for details on my methodological approach [26,27]). I begin by reviewing relevant theoretical and empirical work on water governance and access to resources in postcolonial contexts to set up a framework for deconstructing the implication of planning in producing unmapped water access in the city’s Muslim areas. I then offer an overview of municipal water supply in Ahmedabad, followed by a closer look at how this unfolds in the two administrative units examined. Following this, I turn to specific physical and infrastructural planning processes and investigate their technical roles in governing access to municipal water across Makhtampura and Sarkhej alongside narratives from key actors on the formulation and implementation of these plans. My intent here is to make visible the particulars of whether and how religious difference influences practices of mediation at various points of water governance. The municipal water supply networks in Ahmedabad’s Muslim areas indeed present an instantiation of unmapped water access. However, I argue that an uncomplicated implication of planning processes such as the TPS, in intentionally producing this context, obstructs a closer understanding of how such unmapping comes into being in reality. Using this premise to direct my inquiry, I show how the process of encrypting decisions within planning is a site of intense mediation between actors with varying interests located across the blurry state–non-state boundaries. Though animated by ideological preferences relating to religious differences, this process is simultaneously also vulnerable to economic, legal, and political pressures exerted by a heterogeneous set of actors across the religious divide. The account that follows, while offering an instantiation of the multiples pressures that culminate in water governance unfolding across unstable landscapes of unmapping and mapping, thus, also complicates conventional understandings of majority–minority relations in influencing access to basic services.

2. Water Governance and Access

From a broader environmental resource governance perspective, water governance has been understood as the many “institutional arrangements, spatial scales, organizational structures and social actors involved in making decisions” [28] (p. 236), [29] regarding water resources, the flow of water, who gets to access how much water, through what mechanisms, and so on. Institutional practices produced through a codification of spatio-temporally specific sociopolitical struggles have been located as constituents of governance and determinants of access to resources such as water [30] (pp. 759–760). According to this formulation, “(b)y defining what is economically, technologically, and politically possible at particular moments”, institutional practices lend “coherence and stability” to processes of water governance [30] (pp. 759–760). Institutional arrangements and practices, however, need to be understood as much in terms of objectives they ostensibly are set up to achieve, as well as practical consequences they end up producing. This inquiry, in turn, cannot be adequately conducted without, on the one hand, calling into question the ideological basis and definition of needs that such arrangements and practices are premised upon, and on the other, examining aspects of everyday life that mediate the implementation of codified institutional practices.

Regional water governance in western India, for instance, involves the institutionalization of arrangements enacted through the building of water infrastructures such as large dams ostensibly to mitigate water scarcity in the region. However, the condition of water scarcity that these practices have been predicated upon has itself been called into question with the argument that as opposed to being a natural condition, scarcity is often socially constructed and mediated by myriad socio-political interests [31,32,33]. In other words, as Rittel and Webber assert in their seminal work on “dilemmas” that plague planning propositions, “(t)he choice of explanation determines the nature of the problem’s resolution” [34] (p. 6). The need then is to prise open naturalized conditions upon which institutional practices determining water governance are founded. Furthermore, as has been noted by Grindle and Thomas [35], the journey of a planning proposition from formulation to implementation is not linear, but rather interactive, with actors with diverse interests intervening, mediating, and influencing what gets practically implemented. Indeed, as has been demonstrated by empirical work in cities like Mumbai and Bangalore, the everyday work of producing water access—laying pipes, installing connections, and so on—is often determined by site- and time-specific socio-political and hydraulic conditions [36,37,38], and often the logics directing such work are not in alignment with the abstract planning logics determining how water supply planning and distribution is “conceptualized, materialized and institutionalized” [36] (p. 278). While institutional practices might well be instantiations of dominant power and interests at the time of codification, their implementation is animated by knowledge and authority serving numerous other socio-political and hydraulic interests.

This latter work, in pointing at the need to examine how codified institutional practices shaping water governance are mediated by various kinds of actors in socio-politically specific everyday scenarios, also calls for a disaggregated understanding of forces that influence water access. Water governance has been problematized for over two decades now through critiques of the widespread privatization and commoditization of water that have followed urbanization, globalization, and the growing neoliberal imagination [6,39,40]. Other work has probed water governance using analytical departure points as diverse as context-specific property rights and water rights systems [32,41], attempts at territorial consolidation [42], the violent building of dams to support urbanization [43], the role of caste on the ability to access water [44], and even the relationship between social norms around caste-related access to water to homicides [45]. Notwithstanding the diversity in their points of departure, these studies have powerfully emphasized the need for water governance to be understood through lenses of power relations, social justice, and rights [28,46]. However, for a disaggregated, relational, and politicized understanding of water governance in postcolonial contexts, it is recent work on the everyday mediation of water access by a host of social actors across urban India that holds specific relevance to this paper.

Calling for examining water governance in terms of the conceptual “disembedding” of land and water infrastructures from socio-economic, legal, political, and hydraulic networks in which they are in reality entangled [5], this work highlights the role of myriad social actors—water mafias, water tanker operators, plumbers, local councillors, water department engineers, to name a few—in mediating water access in Indian cities [33,36,38,47]. Building on broader accounts examining the role of “the intermediary”, “the middleman”, “the fixer” [48], “the hustler”, “the hard man”, and “the wheeler-dealer” [49] (p. 15), this scholarship shows how everyday knowledge and authority are constituted, exercised, experienced, and narrated in relation to water governance in India. It instantiates broader assertions on how the Indian state cannot be thought of as a homogenous, predetermined, static entity [50] capable of exercising power on its own [51]. On the one hand, attempts at governing require the state to enlist the support of actors who would, by conventional understandings of the state, be considered non-state [52]. On the other hand, and as a consequence, actions construed and constructed as governance and typically thought to be state directed, are in reality not contained within the ambit of formal government institutions [51]. Instead, governance is posited as “the amalgamated result of the exercise of power by a variety of local institutions and the imposition of external institutions, conjugated with the idea of a state” [51] (p. 686); the state-idea being constituted by qualities, actions, authority, etc., generally associated with government institutions [53] (p. 69). As a result, in postcolonial societies with histories of highly fragmented and distributed knowledge, power, and authority, claims made by governments of being able to exercise “effective legal sovereignty over a territory and its population” are recognized for being particularly tenuous [54] (p. 297).

Accounts of water governance and access in Indian cities have unpacked relationships that residents have with “urban specialists” such as those mentioned above, who “by virtue of their reputation, skills and imputed connections provide services, connectivity and knowledge to ordinary dwellers in slums and popular neighborhoods” [54] (p. 16). In addition, and on the other hand, accounts of “informal sovereigns” talk about influential individuals who, operationalizing the same set of advantages, embody and exert discretionary powers to reward or punish illegalities, make exceptions contravening law, and so on [54] (p. 306). With water shortages increasingly cutting across class lines and legal statuses [55] (p. 499), access to municipal water supply in Indian cities is mediated by actors such as these for a spectrum of interests: From immediate to long-term profit-making or ensuring ‘good business’, demonstrating influence over the state apparatus, making evident the ability to offer social protection, lobbying for political interests, to managing their professional reputations [38] (p. 91). Back in Ahmedabad, it would be impossible to understand the role of institutionalized planning mechanisms vis-à-vis observable unmapped water access in the city’s Muslim areas in any meaningful way without inquiring into the interests of influential individuals and the everyday knowledge and authority exercised by them in mediating the formulation and implementation of plans influencing water governance.

In advancing a ‘theory of access,’ Ribot and Peluso define access as “… the ability to benefit from things—including material objects, persons, institutions and symbols” [56] (p. 153) and make the case for focusing on the ability to benefit from a resource rather than the right to do so. Their formulation presents an alternative to a rights-based, property-centric view. Legally enshrined individual rights, Ribot and Peluso point out, constitute only one set of relationships among many defining access. The ability to benefit from a resource is influenced as much by social relationships and factors such as ideological and discursive manipulations, relations of production and exchange, socially and legally forbidden acts such as theft, corruption, and so on, as by property. In other words, analyzing access requires a close examination of the diverse socio-economic, political, and material powers embodied by institutions, people, processes, and relationships that might influence the ability of people to benefit from a resource [56]. The rubric offered by this ‘theory of access’ is meant to help carry out an access analysis, defined as “the process of identifying and mapping mechanisms by which access is gained, maintained, and controlled” [56] (p. 160). For the access analysis that this paper intends to engage with, two other terms defining access relations become important; control and maintenance, i.e., relations that control the access of others to a resource, as opposed to relations that maintain their access to a resource. It is important to mention here that while the different kinds of powers embodied by these categories might echo the stance of political economy on relations between capital and labor, the narrow confines of ‘class’ are discarded here, and control and maintenance are understood in terms of a broader set of powers that influence the ability to benefit from a resource [56] (p. 159). I turn next to the analytical possibilities these categories offer in probing how religious difference manifests in both control to and maintenance of access to municipal water supply, and locating the role of technical planning processes in influencing these relations.

3. Municipal Water Supply in Ahmedabad

Ahmedabad’s history of piped municipal water supply is over a century old, dating back to 1891, with several water infrastructure projects having been built over the years to meet the city’s growing needs (see [57] for more on this). Before waters from the Narmada river were brought to Ahmedabad 16-odd years ago as a result of the construction of the highly contested and contentious Sardar Sarovar Project, the city depended primarily on its groundwater reserves along with non-perennial surface water sourced from the Sabarmati river. Since 2002 however, it has grown increasingly reliant on Narmada as its primary source of water [58]. Currently, about 75% of Ahmedabad’s total municipally supplied water is reportedly surface water from the Narmada (see Supplementary Materials 5).

Access to municipally supplied Narmada waters is much sought after across Ahmedabad for multiple reasons such as rapidly depleting groundwater levels in drought-prone Gujarat, and Sabarmati waters being non-perennial and having become insufficient; (see [57] for more on this), and indeed, there are numerous accounts describing the revelry in the city when these waters were first brought here (see Supplementary Materials 6 for an example). One much-celebrated consequence of an increasing dependence on Narmada waters for the city’s municipal water supply has been a decreased dependence of the Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation (AMC from here on) on groundwater. According to an official document, until the year 2000, 61% of the city’s municipally supplied water was groundwater, while by 2010, this had reduced to 10% [57,58]. This reduced drawing of groundwater by the AMC for municipal supplies is, however, often conflated with a general decrease in the use of groundwater. For instance, one proactive disclosure by AMC’s water projects department claims that the use of groundwater in Ahmedabad would be completely stopped by 2009–2010, which would mean better health for the city’s residents (see Supplementary Materials 9) [59] (p. 36),. Recent data on groundwater levels, however, belie such projections. Statistics from the Central Groundwater Board show that groundwater levels across Ahmedabad have continued to fall rapidly, not unlike the rest of Gujarat [60] (p. 2). The incongruence between AMC’s projections and CGWB’s findings can be attributed to two facts. First, most middle-income and higher-income neighborhoods in Ahmedabad, despite having legal access to municipal water, continue to draw unchecked amounts of groundwater from their private individual or shared borewells. Water consumption in these neighborhoods is much above the 140 lpcd that the municipal water supplied by the AMC provides for, and the gap between this need and the municipal supply is met by privately drawn unaccounted-for groundwater. Second, households that are unable to access municipally supplied water (legally or illegally) resort to drawing water from the ground, from shared or private borewells, if they have the means to. Simply put, the municipal corporation, having decreased its reliance on groundwater, needs to be disentangled from larger assumptions around the decrease in groundwater use across the city. This, in turn, calls into question the rationale behind bringing Narmada waters to Ahmedabad to begin with, and the logic of the Sardar Sarovar Dam and the Narmada Pipeline Project in extension (see [61] for more on this).

As far as municipal water supply within Ahmedabad is concerned, according to the AMC [58] (p. 11), municipal water supply in the city is directed from source to homes in the following way: (a) Source to (b) treatment plant to (c) trunk mains to (d) local water distribution stations (WDS from here on) and underground tanks to (e) residences. Moments constituting the establishment of water supply from each of these points to the next then become moments of “controlling access”; moments of limiting or facilitating access to municipal water. While the flow of municipal water from source to treatment plant influences the city more broadly, the laying down of trunk mains, building of WDSs and getting water to them, and then getting water to people’s homes from the WDSs through distribution networks are locality- or neighborhood-specific issues.

4. Getting Municipal Water to Makhtampura and Sarkhej

Makhtampura and Sarkhej wards lie in the southern and south-western parts of the city, are occupied predominantly by Muslims, and are administrative units corresponding to the area that much of the scholarship on Ahmedabad’s Muslim community has called Juhapura ([16] for instance). According to estimates by respective Municipal Councillors in 2018, about 95% of the population in Makhtampura ward and 50% of the population in Sarkhej ward is Muslim (see Supplementary Materials 7). Neighborhoods constituting current day Makhtampura and Sarkhej wards were included within AMC limits in 2006 as part of a larger process of expanding the city’s municipal limits and incorporating a total of 259.16 sq. kms. of land from the Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority (AUDA) into the AMC. Prior to their incorporation within the AMC, these neighborhoods were part of villages, and were governed by administrative bodies called ‘gram panchayats’.

The inclusion of an area within the AMC brings with it an important implication in relation to water access: the possibility of accessing Narmada waters, which, as mentioned above, are much more desirable than the groundwater that most villages and municipalities outside of AMC limits depend on. Getting municipally supplied water to flow through an area once it is incorporated with city limits requires the planning and laying of trunk mains and local WDSs, which offer neighborhood-level storage capacity, and then the building of these infrastructures. These processes, in turn, require land and roads to be identified, acquired, and developed by the municipal corporation.

Land for building urban infrastructure in Ahmedabad is made available through a two-stage planning process called the development plan (DP)–town planning scheme (TPS) mechanism and is governed by the Gujarat Town Planning and Urban Development Act (GTPUD Act), 1976. The DP is a metropolitan land-use plan revised roughly every decade by the Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority (AUDA) and serves purportedly as a “comprehensive strategic document for the development of the city” [1] (p. 194). The process of drafting a DP involves the identification of lands on the city’s periphery where urban expansion is deemed likely, followed by the definition of uses for these lands and their rezoning based on population estimates and other projections and needs. As municipal city boundaries expand, lands rezoned from agricultural to other uses by the DP are divided into smaller areas, typically of 100–200 hectares, and detailed plans in the form of TPSs are drawn for them by relevant agencies, i.e., the AMC and AUDA [1,62,63]. The process of developing these plans involves pooling land from land owners, estimating physical and social infrastructure (roads, water distribution stations and networks, sewage plants, schools, hospitals, etc.) that might be required for the rezoned uses, deducting and reserving lands for building this infrastructure, reconstituting plots, and returning them to landowners [1] (pp. 194–198). In addition, land is also deducted during the pooling and reconstitution process towards building land banks of AUDA and AMC. This reserve land is set aside for auctioning, and sold to meet financial needs of the relevant development agency (for details of financial transactions between land-owners and the planning agency involved in this process, see [1] (pp. 198–202), [62] (p. 160). One problem associated with the supply of water and other basic services through TPSs relates to the fact that the TPS mechanism deals only with landowners; it does not engage with informal settlers. This is further complicated by the fact that the ‘landowners’ in question have sometimes been found to be land assemblers and speculators who might have acquired agricultural land by forging documents, coercion and so on. The high level of discretion with which local planning officers prioritise the implementation of specific TPS as well as significant levels of corruption in the planning office are yet other issues to contend with [62] (pp. 169–172)).

The abstract planning logics driving the DP–TPS process, thus, technically influence urban water governance and control access to municipal water supply by: (a) Determining land use and zoning and typically also rezoning from agricultural to other uses, followed by (b) proposing and implementing a TPS, which includes pooling and reconstituting plots to identify and reserve lands for building roads (which would carry the trunk infrastructure and other water pipelines) and water distribution stations (WDS), and (c) defining and laying down water networks to supply municipal water from the WDSs to people’s homes.

5. “There Are No Plots!”

Municipal authorities I spoke with, from both planning and engineering departments alike, cited the inability to build roads and the unavailability of plots for building WDSs as the two biggest obstructions in getting municipal water to many parts of Makhtampura. To understand this claim of “there are no plots!”, it is necessary to discuss the urban history of the area.

Makhtampura started urbanizing in 1973 when flood victims—low-income Hindus and Muslims—from informal settlements along the Sabarmati riverbanks were resettled to a municipal colony here called Sankalit Nagar, built by the AMC, Housing and Urban Development Corporation (HUDCO), and a city-based NGO called the Ahmedabad Study Action Group (ASAG) [16] (p. 69). More low-income Muslim families from the walled city and eastern Ahmedabad moved and settled here after the 1985 riots and again after the 1992 riots. After the 2002 riots, even middle-class and wealthier Muslims started moving here from mixed neighborhoods of the city in search of safety in numbers [16] (p. 69). With this rapidly growing Muslim population, Hindu families moved out of the area. The current (2018) population of Makhtampura is pegged at over 400,000 by the local Councillor.

The sudden influx of people to the area meant that Makhtampura, which was for the most part zoned for agricultural use at the time, went through what might be thought of as a housing crisis. With large numbers of Muslims wanting to live here, a significant share of the post-2002 housing in Makhtampura was hurriedly built on agricultural land either bought legally and subdivided illegally, i.e., subdivided before the area was zoned for residential use, or on agricultural land subdivided after being illegally bought or forcefully captured. These subdivisions were then built upon and sold using quasi-legal documents. Consequently, much of the low-income as well as middle-income housing in the area got built under diverse conditions of illegality before the area had been zoned, planned, or equipped with infrastructure that could support basic services for a large population.

The incorporation of the area within AMC limits in 2006 has meant that people living here are now liable to pay property taxes to the AMC. In total, 30% of these taxes go towards paying for water and sanitation infrastructure. It is important to note that the AMC’s collection of property tax is delinked from the legal tenure status of properties [63] (p. 5), i.e., all properties that fall within AMC limits are charged a municipal property tax. Indeed, the collection of property taxes from informal settlements by the AMC has been understood as a way of increasing tenure security of residents in such areas [63] (p. 5). For residents living in Makhtampura, having become liable to pay municipal property taxes post-2006 has also implied being able to, in turn, hold the municipal corporation liable for providing basic services, including access to municipal water supply. Actually, making municipal water access possible, however, necessitates the planning of water infrastructures—such as determining networks, laying pipelines, building WDSs—by the AMC, which, in turn, requires the corporation to take possession of roads and plots that these infrastructures can be reserved for and built on. It is this context that the planners and engineers draw on while claiming that “there are no plots” to build WDSs, nor roads to lay water pipelines.

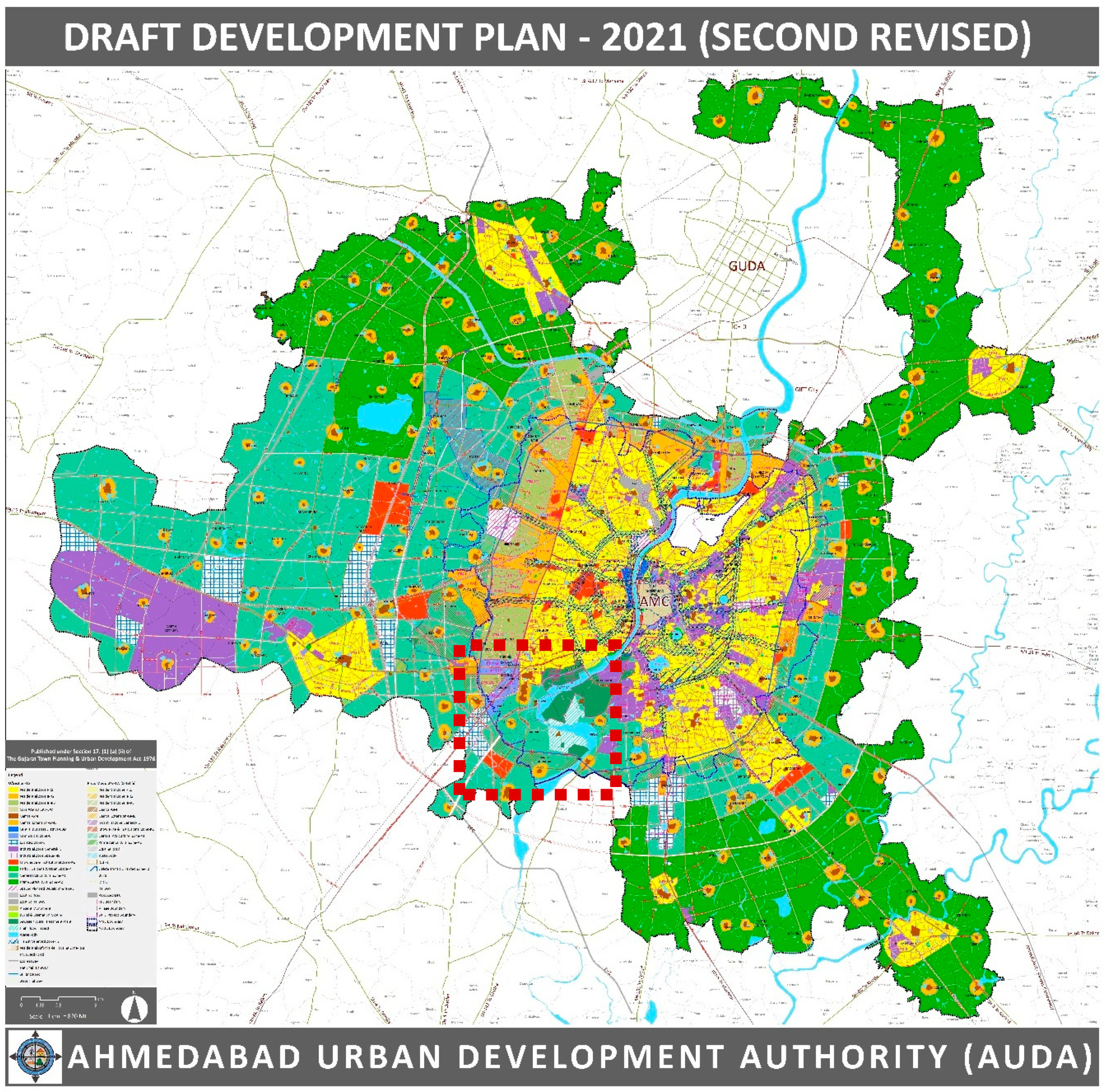

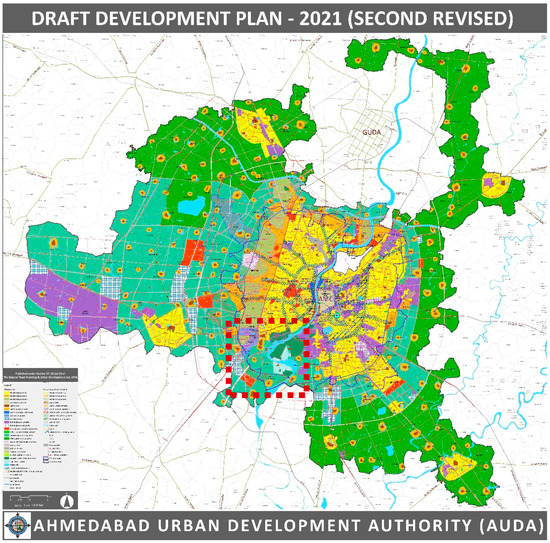

When I asked a senior ward official at Makhtampura about this claimed lack of plots and roads to facilitate access to municipal water supply, he was visibly perturbed. While conceding that identifying and developing plots and roads within the densely constructed areas was problematic, he drew my attention to the large stretches of land to the south of Makhtampura and Sarkhej wards on the revised Development Plan (see Figure 1) designated in part for use as “general agricultural zone” and in part reserved for “sewage treatment plants”. “Agricultural zone means no residential development can be done (sic). TP can also not be done (sic) and so piped municipal water supply is not possible...” he complained.

Figure 1.

Development Plan, 2021, Ahmedabad Urban Development Authority: Source, AUDA. Accessible online at http://www.auda.org.in/RDP/.

A comparison of the most recent DP (for 2021, Figure 1) with the earlier DP (for 2011) shows that lands zoned for sewage treatment plants and agricultural use now, were also zoned so earlier. However, these lands are adjacent to another set of agricultural lands further west, along the corporation’s periphery, which have been rezoned in the most recent DP. The zoning of agricultural lands in Makhtampura has not changed; in fact, the ward official’s quarrel, echoed by the councilor, is that the zoning of agricultural lands in Makhtampura and Sarkhej has remained the same when instead it needed to have been changed in order for this planning process to attend adequately to existing infrastructural needs.

The selective possibilities presented by the DP in rezoning agricultural lands further to the corporation’s periphery while maintaining zoning for lands in Makhtampura and Sarkhej, in the face of complaints by planning and engineering officials about the “lack of plots” are not lost on the ward official or councillor. On the one hand, the proposition of TPSs as well as a promised access to municipal water supply and other basic services are made possible along the periphery of the corporation limits through the rezoning of those agricultural lands for affordable housing. On the other hand, agricultural lands within Makhtampura and Sarkhej wards—wards that desperately need infrastructure for basic services and have repeatedly been denied it, ostensibly for lack of land—continue to remain zoned as before. In the words of the ward official, “How can they say there are no plots when there is so much agricultural land in the wards? They can change the zoning of that land and build public infrastructure. If they want.”

Indeed, in addition to rezoning, there are a few planning mechanisms that can be implemented for re-thinking the use of agricultural lands in Makhtampura (as they have been in other parts of the city) to more sensitively accommodate the community’s needs. One such instance is the ‘overlay zone’ category. In the general development control regulations (GDCR) published under the GTPUD Act, an overlay zone is defined as “an additional zone… with different set (sic) of development regulations over an established/existing base zone to regulate development in such a zone to achieve a specific set of goals defined in the Development Plan” [64] (p. 21). In other words, areas zoned using this mechanism can benefit from uses prescribed for the base zone as well as the overlay zone. The transit zone defined across the city is one such overlay zone, as is the residential affordable housing zone. The need for making exceptions for these two zones, and indeed the ‘will’ to do so, can be found in the introductory sentences of the note on the highlights of the DP, which celebrate the economic benefits that these two zones will offer in terms of floor area as a result of the high-density development made possible here [65]. The complaint of the senior ward engineer then is that, in contrast to revisions to the DP that cater to needs for developing transit and housing infrastructures in adjoining areas, in Makhtampura, despite the shortage of plots to build infrastructure for municipal water supply, no such exceptions have been made. It is in this context that he expresses distress for the widely circulating notion of “there are no plots!”

6. Selective and Uneven Planning?

The TPS process, as mentioned earlier, deals only with land owners and not occupiers [62] (pp. 169–172). Given the large number of illegal constructions in Makhtampura, using the TPS mechanism to build roads for laying trunk infrastructure and acquiring plots to build WDSs here has ostensibly (according to local politicians and engineers) been fraught with difficulties. The challenge in implementing the TPS process to acquire and reserve lands for planning and building physical and social infrastructure in areas with large amounts of informal construction has also been noted in a neighboring Muslim area called Dani Limda [63] (p. 18). But as the authors show in this case, Ahmedabad’s planning authorities are indeed capable of going to quite some lengths to accommodate existing informal constructions (such as changing ratios where allocation of open space is concerned) and make changes to otherwise standard planning norms to map and build basic services. While there must undoubtedly be a specific set of reasons for the AMC to have made exceptions to plan and map infrastructure networks in Dani Limda, a closer look at negotiations between land owners and public authorities in Makhtampura and Sarkhej sheds light on the forces influencing what is mapped and left unmapped on the TPSs here.

One Hindu builder who owns a large share of land within the TPS that much of Makhtampura is also part of, animatedly told me about the protracted negotiations he had carried out with AUDA from 2008 to 2010 to convince the planning authority of the need to not let a major road (meant to carry trunk infrastructure) pass through his land and connect with “the minority community”. Disallowing such a thoroughfare, in his opinion, while being necessary in the “interest of communal harmony”, was also required because building it would “lower the value of property”. Through negotiations that he claimed cost him dearly in money as well as lands that he agreed to hand over to AUDA, he eventually procured development permission for his land based on a masterplan that protected both of his interests cited above. Accounting for the thus passed masterplan, and in agreement with his analysis that a connecting thoroughfare should be disallowed, he recounted, AUDA “had kept a buffer zone” between the Muslim area and his lands. In 2011 however, the AMC took over from AUDA as the planning authority for this area and proposed a draft TPS. The propositions of this TPS, he told me with visibly growing aggravation, disregarded the agreement that he had earlier struck with AUDA over not building this thoroughfare.

Regarded by residents who have bought homes in housing constructed by him as being an honest, liberal man, the builder’s concerns seem grounded in a close understanding of the sentiments of his clientele. As one resident of the housing built by him, pointing at the high barbed wire fencing all along the roughly 4.5 feet walls of the society told me, “there are safety issues. We are right next to this (Muslim) area right? We need to be extra careful. Who knows when there might be trouble!” While barbed wire fencing mounted on compound walls is a phenomenon not limited to the city’s Muslim areas (indeed this is noticeable across the city), the reason cited here, of being “right next to this (Muslim) area” is important in understanding the sentiments held and reproduced by residents of the Hindu society. Another resident, less concerned with so-called “safety issues,” pointed out how being located next to the Muslim area had meant that very few Gujaratis had bought apartments in the society. This housing has primarily been bought by young, working, non-Gujarati professionals, since they “don’t have that history”; the history in reference being that of the widespread Hindu–Muslim violence that Ahmedabad witnessed during the 2002 riots. Being desirable for a limited set of investors has in turn limited the real estate values of this housing.

This is the emotional and economic context that the builder seems to be drawing on while voicing his concerns for maintaining communal harmony as well as protecting real estate values and asserting his insistence on disallowing the thoroughfare. While his concerns relating to religion might well have been a key interest determining the earlier situation of unmapped water access in the neighboring Muslim areas, his concerns themselves are tied up in fears of violence expressed by his clients and echoed broadly across the city. These fears (and in turn, his negotiations with the planning authority) are tied to the builder’s economic fears of reduced property values, making it problematic to assign all liability for the production of unmapped water access to religious difference alone.

The question then arising is: Why did the AMC in the proposed Draft TPS change decisions that the builder had received approval from AUDA on? An enthusiastic retired planner familiar with the area reminded me of a High Court judgement in 2010 (Nadeem vs. State: available online at https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1444997/) which ordered the AMC to “immediately and forthwith provide clean, hygienic and regular supply of drinking water and sewage facilities” to this area. At a hearing earlier that year, the AMC had been asked to present responses to the lack of drinking water and drainage infrastructures here. Presumably—the judgement implies—the AMC had responded by submitting to the court that a certain set of water infrastructures would be built by 2012. The road that the builder did not want built was critical to the construction of the now-promised WDS and trunk infrastructures. The AMC taking over as planning authority for the area and (re-)mapping the road while drafting the TPS also meant a (re-)mapping of earlier unmapped water infrastructures and municipal water access in the area. Negotiations animating what remains unmapped or gets mapped then are tied up in pressures exerted not only by influential individuals but also by public authorities such as the judiciary on formal institutional bodies, and interests driving such variegated pressures are often divergent as this case demonstrates. The process of encrypting decisions in planning propositions thus, far from being a stable one, is fraught with decision-making culminating from clashing interests.

On the one hand, this account points at the highly unstable landscape of shifting power, interests, and negotiations between influential actors (in this case, formal planning authorities, builders and legal landholders, and the judiciary) across which unmapped and mapped access to municipal water unfolds. In cities like Ahmedabad, while concerns relating to religion constitute one set of variables producing this instability, economic interests attached to real estate values, as well as legal and political interests such as heeding directives of the judiciary, constitute other powerful factors animating this landscape. On the other hand, this is also an account of an influential actor, despite having incurred various in-kind and financial costs, being left hung out to dry as a result of instabilities arising from changes in pressures and interests among government institutions. While theoretical and empirical accounts have shown that attempts to govern often involve the state enlisting non-state actors [51], this account demonstrates how powerful non-state actors enlist the state in protecting their own interests. In divided cities, narratives related to religious difference could well be found animating and influencing such processes of enlisting support. However, the extent or success of this influence cannot be thought of as pre-defined or stable but instead as vulnerable to other interests and pressures.

Further complicating this context is the story is of legal Muslim landholders in the area not agreeing to propositions in drafted TPSs because of economic losses (or lower economic gains) the implementation of these planning decisions might imply for them. The TPS allows planning authorities to deduct up to 40% land from individual landholdings through the process of pooling and reconstitution and return the remaining land to landowners. As one influential Muslim builder explained to me, progress on the implementation of most TPSs in Makhtampura is currently at a standstill because the spatial assignment of reconstituted land parcels has not been acceptable to many landowners. In his words, “if your earlier plot was along a 30 mt road, and (after reconstitution) they relocate you along a 12 mt road, nobody is going to tolerate that! That’s when you contest it.” The disadvantage produced by such re-allocations is that of reduced profit. Road widths relate directly to permissible building heights and use; on wider roads, taller buildings can be built on the same plot size, and building uses can also be more diverse (see Supplementary Materials 8). Re-allocated plots on narrower roads directly affect economic interests leading to contestations, in this case between Muslim legal landowners and the planning authorities. The process of finalizing plots and roads for building water infrastructures, thus, in reality, is also tied up in legal disputes arising from such disagreements.

The instance of Muslim landowners obstructing the implementation of TPSs complicates frequently repeated allegations (such as those presented by the opening quotes of this paper) holding the TPS responsible for the production of unmapped water access based on religious difference. It shows how observable unmapped access to municipal water might well be a result of powerful non-state actors of the same religious identity obstructing the implementation of planning propositions for protecting their personal economic interests. This account then adds nuance to accounts of poor water access in Muslim areas of Indian cities (such as [33]) which assert the role of local (Muslim) influential actors in challenging uneven water access and making the state accessible. In Ahmedabad too, a number of local influential Muslim actors such as Haji Mirza, a councilor from Makhtampura, have indeed played an important role in facilitating municipal water access in the area by filing public interest litigations at the Gujarat High Court which in turn have influenced judicial directives on building water infrastructures, as well as rallying for basic services with the corporation. However, there are other equally influential Muslim actors whose economic interests are at loggerheads with the implementation of plans required for building water infrastructures in currently underserved areas and who have ended up obstructing municipal water access. This situation is not peculiar to Muslim parts of the city. Legal landholders from across Ahmedabad routinely enter into contestations with planning authorities in relation to TPS propositions for protecting their economic interests. In Ahmedabad’s Muslim areas however, the easily accessible explanation of ubiquitous illegalities and the direct and causal implication of TPSs (and in relation of the state) for deliberately unmapping water access on account of religion, occludes the micro-politics that in reality animate this context.

This account renders unstable the conflation of the complaint that “there are no plots”, or indeed that there are no roads, and the consequent deadlock in implementing TPSs, with illegal constructions in Makhtampura and Sarkhej. As demonstrated above, it might indeed be demands and pressures by legal land owners—both Hindu and Muslim—preventing the construction of roads and, in turn, the building of water infrastructures. Extending Gupta’s assertion on corruption—that “the phenomena of corruption cannot be grasped apart from, or in isolation from, narratives of corruption” [66] (p. 6)—I argue that the TPSs in Makhtampura and Sarkhej being suspended in animation cannot be understood in isolation from discourses, interests, and negotiations that lead to such a phenomenon coming into being. The implementation of the DP and the TPS controls—makes possible, or obstructs—the laying of trunk infrastructure and the construction of WDSs, which in turn, determines the ability or inability of a neighborhood to legally receive municipal water supply. However, the process of encrypting decisions within plans is itself a site of intense and volatile mediation unfolding across blurred boundaries of legality and illegality between actors with varying interests.

7. In Conclusion: “The Main Reason You Know, Is Political”

Developing a closer understanding of ideologies, practices, and interests animating contexts of unmapped water access in sites divided by religious difference is important since this, in turn, has implications on how the issue of problematic water access in minority areas is further addressed. In other words, if unmapped water access in divided landscapes needs to be challenged, the definition of how it comes into being is critical. This calls for the need to pay close attention to discourses and pressures mediating how an area is mapped or unmapped. Presenting an inquiry of this nature, the account of uneven water access offered here is illustrative of how decisions embodied by technical plans need to be understood as a culmination of intense mediations between influential state and non-state actors with varying interests. In divided cities like Ahmedabad, while mediations driven by discourses on religious difference might well be a powerful force influencing the formulation of plans and facilitating access to municipal water, these plans are simultaneously also vulnerable to other political, legal, and economic pressures. Water governance as a result unfolds in an unstable landscape of unmapping and mapping, with religious difference being only one variable influencing the instability.

Much of the work on access to housing and basic services in cities of the south divided by religion, insightful and instructive in its own right, has organized its inquiries across two broad registers; (1) vis-à-vis the instrumental role of religious organizations in providing these [67,68], and (2) as majoritarian groups exerting control over land and resources [13,69]. However, majority and minority groups are often thought to be divergent but homogenous in themselves, operating from ideals and interests contained neatly within confines of religious identity. The account of uneven water access in Ahmedabad’s Muslim areas complicates such assumptions and shows how contestations and negotiations influencing observable unmapped conditions in divided cities might in reality be operating across religious divides. In other words, while a city might present stark physical divisions based on religion, and indeed religion might have been the basis for such divisions to have come into being historically, pressures influencing the reproduction of spatial and infrastructural differences over time might not be aligned along religious divides alone. While the Hindu builder’s earlier efforts had likely influenced the persistence of unmapping in Makhtampura and Sarkhej, it is now contestations by Muslim builders and landowners constituting pressures leading to observable unmapped municipal water access. Though the former negotiations were indeed animated by emotional and economic concerns relating to religious differences, prevailing contestations are founded on economic interests of protecting real estate values and ensuring profit-maximization.

Through this inquiry, I have sought to make visible mediations constituting the backdrop for planning propositions in divided cities becoming formulated and implemented (or not implemented) in specific ways. For engineers and planners, the oft-reproduced rhetoric of illegal constructions that have developed post-2002 as a result of the sudden and large influx of Muslims to Makhtampura and Sarkhej has become an easy way of explaining away the uneven implementation of TPSs here. The impossibility of implementing TPSs, in turn, has become the official, further-reproduced explanation for observable unmapped water access. As this account suggests however, it might well be social, political, and economic concerns by legal landowners leading to the uneven implementation of TPSs. Accepting direct causality between planning propositions and observable unmapped water access in minority areas and locating intentionality wholly (and only) in state-led actions occludes the micro-politics that, in reality, animate this context and prevents a more informed approach to where change might need to be located to facilitate better water access for minority communities.

For water governance in divided cities such as Ahmedabad then, this account points at the need to challenge uncomplicated implications of planning mechanisms in producing unmapped water access based on religious difference alone. Contributing to work destabilizing the notion of planning as a technical, static, pre-determined practice, I suggest instead the need to investigate the entanglement of planning processes with economic, social, legal, and political interests of influential actors from both minority and majority groups, and from varying locations across the blurry state–non-state boundary. Institutionalized planning practices, such as the TPS in this case, might simply be discursive categories around which uneven water access coalesces. As a veteran planner closely familiar with the area told me: “the main reason you know, is political”.

Supplementary Materials

This part are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4441/11/6/1282/s1.

Funding

This work is based on research that was generously supported by IDRC through a Doctoral Research Award (IDRA 10279-027). I am immensely grateful to IDRC for awarding me the IDRC Doctoral Research Award, which made it possible for me to stay in Ahmedabad for an extended period of time and conduct my fieldwork.

Acknowledgments

I extend sincere thanks to Lisa Bjorkman, Jordi Honey-Roses, Michael Leaf, the anonymous reviewers for this paper, and the editors of this special issue for critical and insightful comments to the draft, which helped sharpen my argument.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ballaney, S.; Patel, B. Using the Development Plan—Town Planning Scheme Mechanism to Appropriate Land and Build Urban Infrastructure. In India Infrastructure Report 2009: Land—A Critical Resource for Infrastructure; Oxford University Press: New Delhi, India, 2009; pp. 190–204. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, A. Why India cannot plan its cities: Informality, insurgence and the idiom of urbanization. Plan. Theory 2009, 8, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, V. Seeing from the South: Refocusing Urban Planning on the Globe’s Central Urban Issues. Urban Stud. 2009, 46, 2259–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T. Rule of Experts: Egypt, Techno-politics, Modernity; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkman, L. Pipe Politics, Contested Waters: Embedded Infrastructures of Millennial Mumbai; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, K. Privatizing Water: Governance Failure and the World’s Urban Water Crisis; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pulido, L. A Critical Review of the Methodology of Environmental Racism Research. Antipode 1996, 28, 142–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, A. The Return of the Slum: Does Language Matter? Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2007, 31, 697–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz, N. Planning with Resurgent religion: Informality and gray spacing of the urban landscape. Plan. Theory Pract. 2015, 16, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSayyad, N. The Fundamentalist City? Religiosity and the Remaking of Urban Space; AlSayyad, N., Mejgan, M., Eds.; Routledge: Oxon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Yiftachel, O. Theoretical Notes on Gray Cities: The Coming of Urban Apartheid? Plan. Theory 2009, 8, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiftachel, O. Re-engaging Planning Theory? Towards South-Eastern Perspectives. Plan. Theory 2006, 5, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiftachel, O. Ethnocracy: Land and Identity Politics in Israel/Palestine; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Yiftachel, O.; Yakobi, H. Control, Resistance and Informality: Urban Ethnocracy in Beer-Sheva, Israel. In Urban Informality: Transnational Perspectives from the Middle East, Latin America and South Asia; Roy, A., AlSayyad, N., Eds.; Lexington Books: Lanham, MD, USA, 2004; pp. 209–239. [Google Scholar]

- Spodek, H. Ahmedabad: Shock City of Twentieth-Century India; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffrelot, C.; Thomas, C. Facing Ghettoisation in Riot-city. Old Ahmedabad and Juhapura between Victimisation and Self-help. In Muslims in Indian Cities: Trajectories of Marginalisation; Gayer, L., Cristophe, J., Eds.; Hurst & Co.: London, UK, 2012; pp. 43–80. [Google Scholar]

- Desai, R. Producing and Contesting the Communalized City. In The Fundamentalist City? Religiosity and the Remaking of Urban Space; AlSayyad, N., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2011; pp. 99–124. [Google Scholar]

- Chandhoke, N.; Priyadarshi, P.; Tyagi, S.; Khanna, N. The Displaced of Ahmedabad. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 2007, 42, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Chandhoke, N. Some Reflections on the Notion of an Inclusive Political Pact: A Perspective from Ahmedabad; Working Paper No. 71; Crisis States Working Papers Series No.2; Crisis States Research Centre, London School of Economics and Political Science: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mander, H. Inside Gujarat’s Relief Colonies: Surviving State Hostility and Denial. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 2006, 41, 5235–5239. [Google Scholar]

- Breman, J. The Making and Unmaking of an Industrial Working Class: Sliding Down the Labour Hierarchy in Ahmedabad, India; Oxford University Press: New Delhi, India, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevia, D. Communal Space over Life Space: Saga of Increasing Vulnerability in Ahmedabad. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 2002, 37, 4850–4858. [Google Scholar]

- Mawani, V.; Leaf, M. Informality and Exclusion in Ahmedabad. In The Routledge Handbook on Informal Urbanisatio; Rocco, R., Ballegooijen, J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Larkin, B. The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2013, 42, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlove, B.; Caton, S. Water Sustainability: Anthropoloigical Approaches and Prospects. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2010, 39, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.; Gregor, F. Mapping Social Relations: A Primer in Doing Institutional Ethnography; Garamond Press: Aurora, ON, Canada, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D.E. Institutional Ethnography: A Sociology for People; Altamira Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Perreualt, T. What kind of governance for what kind of equity? Towards a theorization of justice in water governance. Water Int. 2014, 39, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himley, M. Geographies of environmental governance: The nexus of nature and neoliberalism. Geogr. Compass 2008, 2, 433–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridge, G.; Jonas, A.E. Governing nature: The reregulation of resource access, production, and consumption. Environ. Plan. A 2002, 34, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, L. The Manufacture of Popular Perceptions of Scarcity: Dams and Water-Related Narratives in Gujarat, India. World Dev. 2001, 29, 2025–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, L. Whose scarcity? Whose property? The case of water in western India. Land Use Policy 2007, 24, 654–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contractor, Q. Quest for Water: Muslims at Mumbai’s Periphery. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 2012, 47, 61–67. [Google Scholar]

- Rittel, H.W.J.; Webber, M.M. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grindle, M.; Thomas, J. Public Choices and Policy Change: The Political Economy of Reform in Developing Countries; John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkman, L. The engineer and the plumber: Mediating Mumbai’s Conflicting Infrastructural Imaginaries. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2018, 42, 276–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, N. Hydraulic City: Water and the Infrastructures of Citizenship in Mumbai; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ranganathan, M. Mafias in the Waterscape: Urban Informality and Everyday Public Authority in Bangalore. Water Altern. 2014, 7, 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Swyngedow, E. Social Power and the Urbanization of Water: Flows of Power; Oxford University Press: Oxford, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, K. The commons versus the commodity: Alter-globalization, anti-privatization and the human right to water in the global South. Antipode 2007, 39, 430–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boelens, R. The politics of disciplining water rights. Dev. Chang. 2009, 40, 307–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, L.; Alatout, S. Negotiating hydro-scales, forging states: Comparison of the upper Tigris/Euphrates and Jordan river basins. Polit. Geogr. 2010, 29, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baviskar, A. In the Belly of the River: Tribal Conflicts over Development in the Narmada Valley; Oxford University Press: Delhi, India, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, S.; Behera, S.; Bharti, A. Access to Drinking Water by Scheduled Castes in Rural India: Some Key Issues and Challenges. Indian J. Hum. Dev. 2015, 9, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bros, C.; Couttenier, M. Untouchability, homicides and water access. J. Comp. Econ. 2015, 43, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirosa, O.; Harris, L. Human right to water: Contemporary challenges and contours of a global debate. Antipode 2012, 44, 932–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, N. Pressure: The Politechnics of water supply in Mumbai. Cult. Anthropol. 2011, 26, 542–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, R.G.; Haragopal, G. The Pyraveekar: The Fixer in Rural India. Asian Surv. 1985, 25, 1148–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blom Hansen, T.; Verkaaik, O. Introduction—Urban Charisma: On Everyday Mythologies in the City. Crit. Anthropol. 2009, 29, 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J.; Gupta, A. Spatializing States: Toward an Ethnography of Neoliberal Governmentality. Am. Ethnol. 2002, 29, 981–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessop, B. State Theory: Putting the Capitalist State in Its Place; Cambridge Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, C. Twilight institutions: Public authority and local politics in Africa. Dev. Chang. 2006, 37, 685–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, P. Notes on the Difficulty of Studying the State. J. Hist. Sociol. 1988, 1, 58–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, T.B.; Stepputat, F. Sovereignty Revisited. Ann. Rev. Anthropol. 2006, 35, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorkman, L. Un/known Waters: Navigating Everyday Risks of Infrastructural Breakdown in Mumbai. Comp. Stud. South Asia 2014, 34, 497–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribot, J.; Peluso, N. A Theory of Access. Rural Sociol. 2003, 68, 153–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.M.; Singh, N.P.; Shah, K.A.; Gamit, J.H. Performance Evaluation of Water Supply Services in Developing Country: A Case Study of Ahmedabad City. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2014, 18, 1984–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AMC. Water Supply and Sanitation in Ahmedabad City; Preparing for the Urban Challenges of 21st Century; Icrier: New Delhi, India, 2013; Available online: http://icrier.org/pdf/ahemadbad_water.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2018).

- AMC. Date Uncertain: Proactive Disclosures under RTI-Act: Water Project Department; Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation: Ahmedabad, India. Available online: https://ahmedabadcity.gov.in/portal/jsp/Static_pages/water_project.jsp (accessed on 5 November 2018).

- CGWB. Groundwater Yearbook 2015–16; Gujarat state and UT of Daman and Diu: Central Groundwater Board; Ministry of Water Resources Government of India: New Delhi, India, 2016. Available online: http://cgwb.gov.in/Regions/GW-year-Books/GWYB-2015-16/GWYB%20WCR%202015-16.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2018).

- Luxion, M. Nation-building, industrialisation, and spectacle: Political functions of Gujarat’s Narmada Pipeline Project. Water Altern. 2017, 10, 208–232. [Google Scholar]

- Sanyal, B.; Deuskar, C. A Better Way to Grow? Town Planning Schemes as a Hybrid Land Readjustment Process in Ahmedabad, India. In Value Capture and Land Policies; Ingram, G., Hong, Y.-H., Eds.; Lincoln Institute of Land Policy: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevia, D.; Pai, M.; Mahendra, A. Ahmedabad: Town Planning Schemes for Equitable Development-Glass Half Full or Half Empty? World Resources Report Case Study; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.wri.org/wri-citiesforall/publication/ahmedabad-town-planning-schemes-equitable-development-glass-half-full (accessed on 17 June 2019).

- AUDA. General Development Control Regulations. Government of Gujarat, 2017. Available online: http://www.auda.org.in/uploads/Assets/rdp/test02142019031034856.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2019).

- AUDA. Second Revised Development Plan. 2013. Available online: http://www.auda.org.in/uploads/Assets/rdp/Note%20on%20Revised%20Development%20Plan%202021.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2019).

- Gupta, A. Narratives of Corruption: Anthropological and fictional accounts of the Indian state. Ethnography 2005, 6, 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harb, M. On Religiosity and Spatiality: Lessons from Hezbollah in Beirut. In The Fundamentalist City? Religiosity and the Remaking of Urban Space; AlSayyad, N., Massoumi, M., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2011; pp. 125–154. [Google Scholar]

- Giovannini, F. Hamas in Gaza Refugee Camps: The Construction of Trapped Spaces for the Survival of Fundamentalism. In The Fundamentalist City? Religiosity and the Remaking of Urban Space; AlSayyad, N., Massoumi, M., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2011; pp. 155–174. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai, A. Spectral housing and urban cleansing: Notes on Millenial Mumbai. Public Cult. 2000, 12, 627–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).