Recent Trends in Removal Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products by Electrochemical Oxidation and Combined Systems

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Origins and Classification of PPCPs

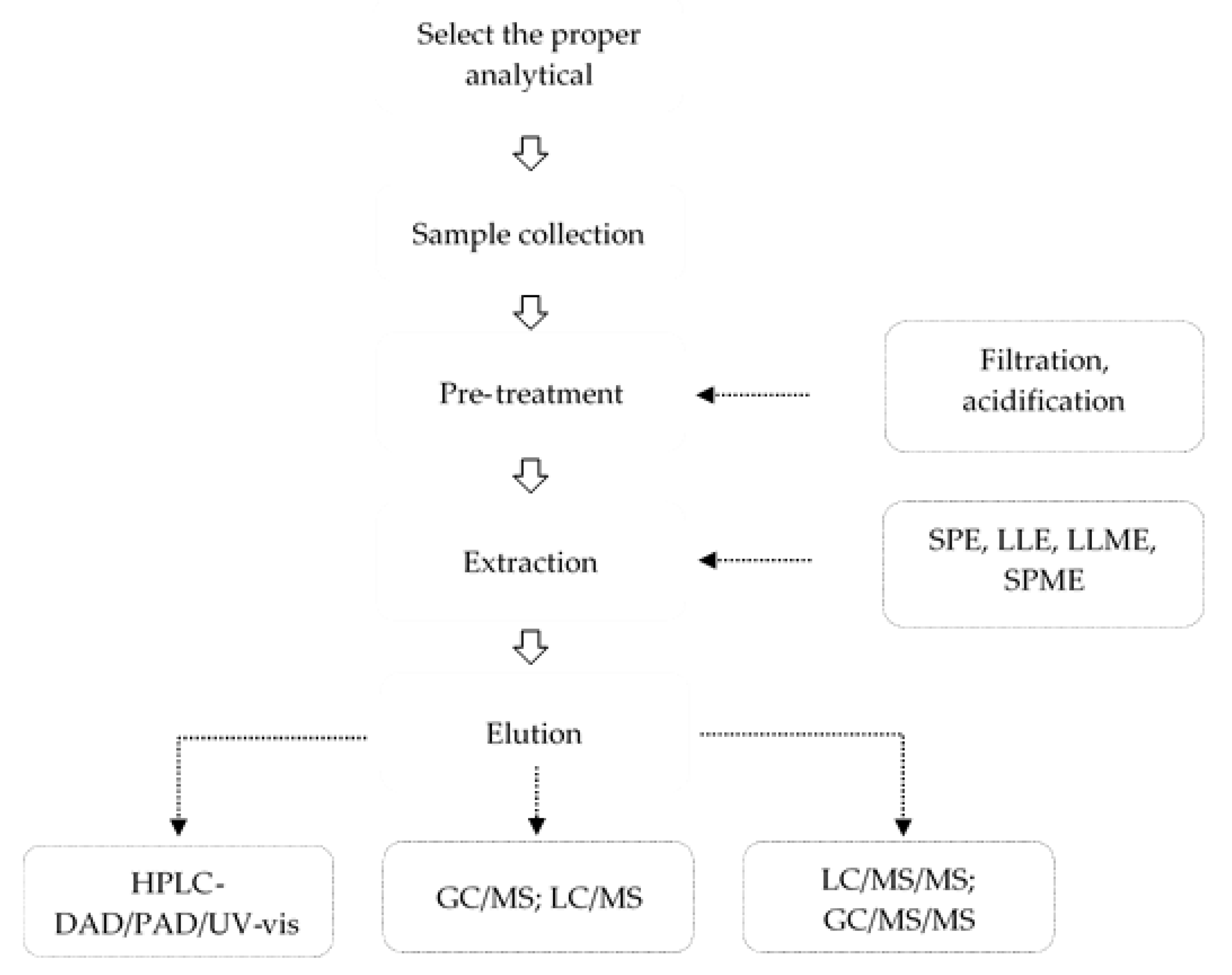

3. Analytical Methods of PPCPs

4. Removal of PPCPs from Liquid Solutions by EOP

4.1. Electrochemical Reactor Designs and Configurations

4.2. Electrode Materials

4.2.1. Lead and Lead Dioxide

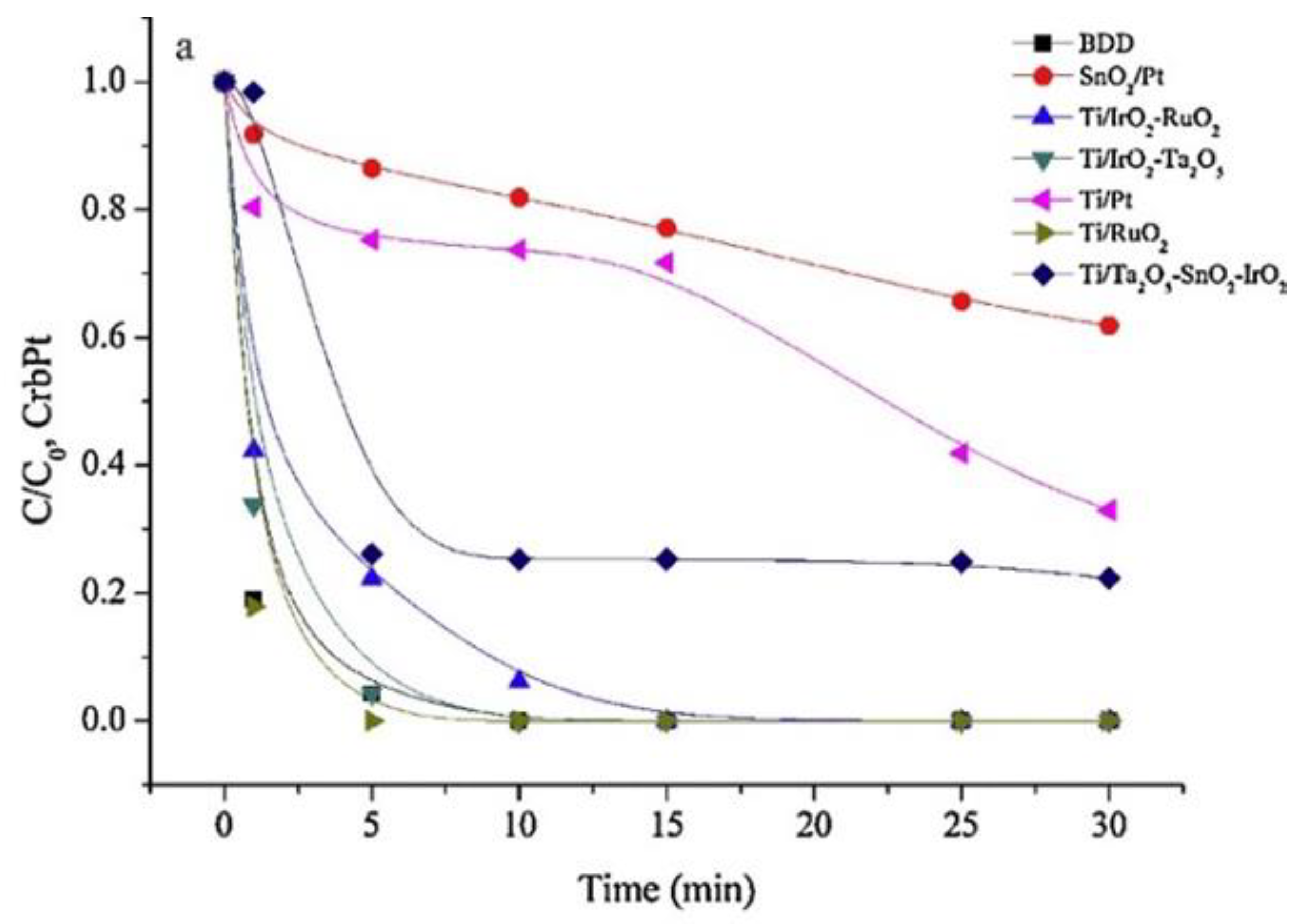

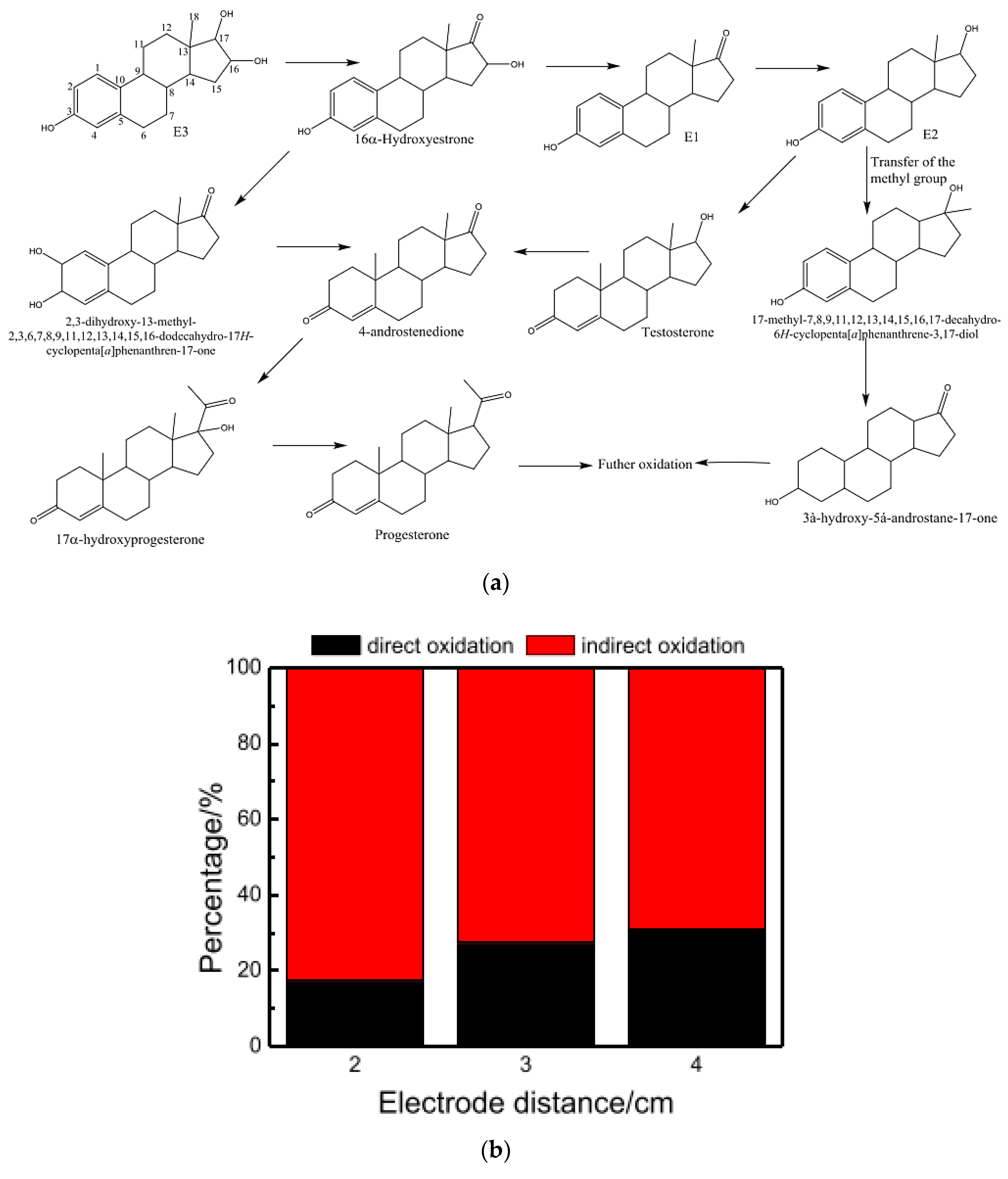

4.2.2. DSA

4.2.3. Boron-Doped Diamond

4.2.4. Other Electrodes

4.3. Influence of Operational Parameters

4.3.1. Initial PPCPs Concentration

4.3.2. Supporting Electrolytes

4.3.3. Current Density, pH, Temperature, and Stirring Rate

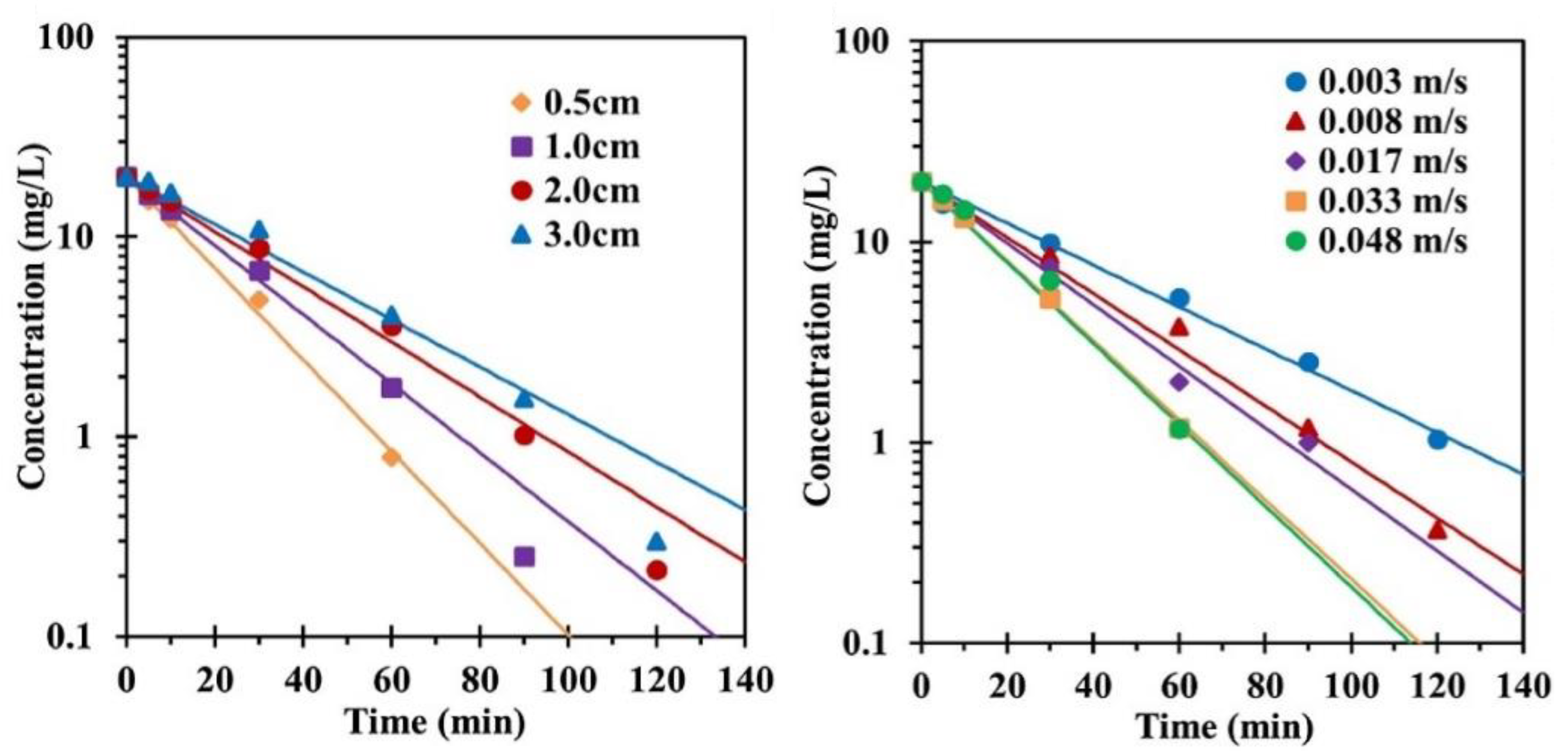

4.3.4. Electrode Spacing and Fluid Velocity

4.4. Applications for Real Water and Wastewater Containing PPCPs

4.5. Combined Systems

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shen, R.; Andrews, S.A. Demonstration of 20 pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) as nitrosamine precursors during chloramine disinfection. Water Res. 2011, 45, 944–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boxall, A.B.; Rudd, M.A.; Brooks, B.W.; Caldwell, D.J.; Choi, K.; Hickmann, S.; Innes, E.; Ostapyk, K.; Staveley, J.P.; Verslycke, T. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in the environment: What are the big questions? Environ. Health Perspect. 2012, 120, 1221–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deblonde, T.; Cossu-Leguille, C.; Hartemann, P. Emerging pollutants in wastewater: A review of the literature. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2011, 214, 442–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajapaksha, A.U.; Vithanage, M.; Lim, J.E.; Ahmed, M.B.M.; Zhang, M.; Lee, S.S.; Ok, Y.S. Invasive plant-derived biochar inhibits sulfamethazine uptake by lettuce in soil. Chemosphere 2014, 111, 500–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helbling, D.E.; Hollender, J.; Kohler, H.-P.E.; Singer, H.; Fenner, K. High-throughput identification of microbial transformation products of organic micropollutants. Environ. Sci. Technol. Water Treat. 2010, 44, 6621–6627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, K.; Bhandari, A.; Das, K.; Pillar, G. Occurrence and fate of pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) in biosolids. J. Environ. Qual. 2005, 34, 91–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, B.D.; Crago, J.P.; Hedman, C.J.; Klaper, R.D. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products found in the Great Lakes above concentrations of environmental concern. Chemosphere 2013, 93, 2116–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiron, S.; Minero, C.; Vione, D. Photodegradation processes of the antiepileptic drug carbamazepine, relevant to estuarine waters. Environ. Sci. 2006, 40, 5977–5983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolls, J. Sorption of veterinary pharmaceuticals in soils: A review. Environ. Sci. Technol. Water Treat. 2001, 35, 3397–3406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panizza, M.; Cerisola, G. Direct and mediated anodic oxidation of organic pollutants. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 6541–6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollender, J.; Zimmermann, S.G.; Koepke, S.; Krauss, M.; McArdell, C.S.; Ort, C.; Singer, H.; von Gunten, U.; Siegrist, H. Elimination of organic micropollutants in a municipal wastewater treatment plant upgraded with a full-scale post-ozonation followed by sand filtration. Environ. Sci. Technol. Water Treat. 2009, 43, 7862–7869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Huitle, C.A.; Ferro, S. Electrochemical oxidation of organic pollutants for the wastewater treatment: Direct and indirect processes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 1324–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaestner, M.; Nowak, K.M.; Miltner, A.; Trapp, S.; Schaeffer, A. Classification and modelling of nonextractable residue (NER) formation of xenobiotics in soil–a synthesis. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. Water Treat. 2014, 44, 2107–2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallenborn, R. Perfluorinated Alkylated Substances (PFAS) in the Nordic Environment; Nordic Council of Ministers: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Daughton, C.G.; Ternes, T.A. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products in the environment: Agents of subtle change? Environ. Health Perspect. 1999, 107, 907–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golet, E.M.; Alder, A.C.; Hartmann, A.; Ternes, T.A.; Giger, W. Trace determination of fluoroquinolone antibacterial agents in urban wastewater by solid-phase extraction and liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection. Anal. Chem. 2001, 73, 3632–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lishman, L.; Smyth, S.A.; Sarafin, K.; Kleywegt, S.; Toito, J.; Peart, T.; Lee, B.; Servos, M.; Beland, M.; Seto, P. Occurrence and reductions of pharmaceuticals and personal care products and estrogens by municipal wastewater treatment plants in Ontario, Canada. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 367, 544–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.; Kumar, A.; Du, J.; Hepplewhite, C.; Ellis, D.J.; Christy, A.G.; Beavis, S.G. Pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) in Australia’s largest inland sewage treatment plant, and its contribution to a major Australian river during high and low flow. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 541, 1625–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Wu, L.; Chang, A.C. Seasonal variation of endocrine disrupting compounds, pharmaceuticals and personal care products in wastewater treatment plants. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 442, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín, J.; Camacho-Muñoz, D.; Santos, J.L.; Aparicio, I.; Alonso, E. Occurrence and ecotoxicological risk assessment of 14 cytostatic drugs in wastewater. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2014, 225, 1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ternes, T.A.; Bonerz, M.; Herrmann, N.; Teiser, B.; Andersen, H.R. Irrigation of treated wastewater in Braunschweig, Germany: An option to remove pharmaceuticals and musk fragrances. Chemosphere 2007, 66, 894–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, G.; Song, Y.-H.; Zeng, P.; Duan, L.; Xiao, S. Characterization of bacterial communities in hybrid upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB)–membrane bioreactor (MBR) process for berberine antibiotic wastewater treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 142, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosal, R.; Rodríguez, A.; Perdigón-Melón, J.A.; Petre, A.; García-Calvo, E.; Gómez, M.J.; Agüera, A.; Fernández-Alba, A.R. Occurrence of emerging pollutants in urban wastewater and their removal through biological treatment followed by ozonation. Water Res. 2010, 44, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclercq, M.; Mathieu, O.; Gomez, E.; Casellas, C.; Fenet, H.; Hillaire-Buys, D. Presence and fate of carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and seven of their metabolites at wastewater treatment plants. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2009, 56, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenz, K.; Hann, S.; Koellensperger, G.; Stefanka, Z.; Stingeder, G.; Weissenbacher, N.; Mahnik, S.N.; Fuerhacker, M. Presence of cancerostatic platinum compounds in hospital wastewater and possible elimination by adsorption to activated sludge. Sci. Total Environ. 2005, 345, 141–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Yan, K.; Wang, Z.; Torres, O.L.; Guo, R.; Chen, J. A new disposal method for systematically processing of ceftazidime: The intimate coupling UV/algae-algae treatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 314, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junker, T.; Alexy, R.; Knacker, T.; Kümmerer, K. Biodegradability of 14C-labeled antibiotics in a modified laboratory scale sewage treatment plant at environmentally relevant concentrations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 318–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watkinson, A.J.; Murby, E.J.; Costanzo, S.D. Removal of antibiotics in conventional and advanced wastewater treatment: Implications for environmental discharge and wastewater recycling. Water Res. 2007, 41, 4164–4176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, H.W.; Minh, T.B.; Murphy, M.B.; Lam, J.C.; So, M.K.; Martin, M.; Lam, P.K.; Richardson, B.J. Distribution, fate and risk assessment of antibiotics in sewage treatment plants in Hong Kong, South China. Environ. Int. 2012, 42, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhang, G.; Li, X.; Zou, S.; Li, P.; Hu, Z.; Li, J. Occurrence and elimination of antibiotics at four sewage treatment plants in the Pearl River Delta (PRD), South China. Water Res. 2007, 41, 4526–4534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, B.; Nikolaus, A.; Hedman, C.; Klaper, R.; Grundl, T. Evaluating the degradation, sorption, and negative mass balances of pharmaceuticals and personal care products during wastewater treatment. Chemosphere 2015, 134, 395–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, R.; Oehmen, A.; Carvalho, G.; Noronha, J.P.; Reis, M.A. Biodegradation of clofibric acid and identification of its metabolites. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 241, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Lv, M.; Hu, A.; Yang, X.; Yu, C.P. Seasonal variation in the occurrence and removal of pharmaceuticals and personal care products in a wastewater treatment plant in Xiamen, China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 277, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, K.; Soares, A.D.; Adejumo, H.; McDiarmid, M.; Squibb, K.; Blaney, L. Detection of a wide variety of human and veterinary fluoroquinolone antibiotics in municipal wastewater and wastewater-impacted surface water. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2015, 106, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voets, J.P.; Pipyn, P.; Van Lancker, P.; Verstraete, W. Degradation of microbicides under different environmental conditions. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1976, 40, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasse, C.; Schlusener, M.P.; Schulz, R.; Ternes, T.A. Antiviral drugs in wastewater and surface waters: A new pharmaceutical class of environmental relevance? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 1728–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonich, S.L.; Federle, T.W.; Eckhoff, W.S.; Rottiers, A.; Webb, S.; Sabaliunas, D.; De Wolf, W. Removal of fragrance materials during US and European wastewater treatment. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 2839–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakada, N.; Tanishima, T.; Shinohara, H.; Kiri, K.; Takada, H. Pharmaceutical chemicals and endocrine disrupters in municipal wastewater in Tokyo and their removal during activated sludge treatment. Water Res. 2006, 40, 3297–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molins-Delgado, D.; Díaz-Cruz, M.S.; Barceló, D. Ecological risk assessment associated to the removal of endocrine-disrupting parabens and benzophenone-4 in wastewater treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 310, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, H.; Du, J.; Qu, Y.; Shen, C.; Tan, F.; Chen, J.; Quan, X. Occurrence, removal, and risk assessment of antibiotics in 12 wastewater treatment plants from Dalian, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2017, 24, 16478–16487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosma, C.I.; Lambropoulou, D.A.; Albanis, T.A. Occurrence and removal of PPCPs in municipal and hospital wastewaters in Greece. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 179, 804–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verlicchi, P.; Al Aukidy, M.; Zambello, E. Occurrence of pharmaceutical compounds in urban wastewater: Removal, mass load and environmental risk after a secondary treatment—A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2012, 429, 123–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huddleston, J.G.; Willauer, H.D.; Swatloski, R.P.; Visser, A.E.; Rogers, R.D. Room temperature ionic liquids as novel media for ‘clean’liquid–liquid extraction. Chem. Commun. 1998, 1765–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadhosseini, M.; Tehrani, M.S.; Ganjali, M.R. Preconcentration, determination and speciation of chromium (III) using solid phase extraction and flame atomic absorption spectrometry. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2006, 53, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajeshwar, K.; Ibanez, J.G. Environmental Electrochemistry: Fundamentals and Applications in Pollution Sensors and Abatement; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wendt, H.; Kreysa, G. Electrochemical Engineering: Science and Technology in Chemical and Other Industries; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Periyasamy, S.; Muthuchamy, M. Electrochemical oxidation of paracetamol in water by graphite anode: Effect of pH, electrolyte concentration and current density. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 7358–7367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, S.W.; do Prado, J.M.; Heberle, A.N.A.; Schneider, D.E.; Rodrigues, M.A.S.; Bernardes, A.M. Electrochemical advanced oxidation of Atenolol at Nb/BDD thin film anode. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2019, 844, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-J.; Hu, C.-Y.; Lo, S.-L. Direct and indirect electrochemical oxidation of amine-containing pharmaceuticals using graphite electrodes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 366, 592–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Montoya, M.F.; Gutiérrez-Granados, S.; Alatorre-Ordaz, A.; Galindo, R.; Ornelas, R.; Peralta-Hernandez, J.M.; Chemistry, E. Application of electrochemical/BDD process for the treatment wastewater effluents containing pharmaceutical compounds. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015, 31, 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Gomez, J.; Ortega, E.; Mestre, S.; Pérez-Herranz, V.; García-Gabaldón, M. Electrochemical degradation of norfloxacin using BDD and new Sb-doped SnO2 ceramic anodes in an electrochemical reactor in the presence and absence of a cation-exchange membrane. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 208, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-S.; Chen, P.-H.; Huang, K.-L. Electrochemical degradation of N, N-diethyl-m-toluamide on a boron-doped diamond electrode. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2014, 45, 2615–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillas, E.; Sires, I.; Arias, C.; Cabot, P.L.; Centellas, F.; Rodriguez, R.M.; Garrido, J.A. Mineralization of paracetamol in aqueous medium by anodic oxidation with a boron-doped diamond electrode. Chemosphere 2005, 58, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, E.B.; Garcia-Segura, S.; Centellas, F.; Brillas, E. Electrochemical incineration of omeprazole in neutral aqueous medium using a platinum or boron-doped diamond anode: Degradation kinetics and oxidation products. Water Res. 2013, 47, 1803–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Xia, Y.; Sun, C.; Weng, M.; Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, J. Electrochemical degradation of levodopa with modified PbO2 electrode: Parameter optimization and degradation mechanism. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 245, 359–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radjenovic, J.; Bagastyo, A.; Rozendal, R.A.; Mu, Y.; Keller, J.; Rabaey, K. Electrochemical oxidation of trace organic contaminants in reverse osmosis concentrate using RuO2/IrO2-coated titanium anodes. Water Res. 2011, 45, 1579–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopaj, F.; Rodrigo, M.A.; Oturan, N.; Podvorica, F.I.; Pinson, J.; Oturan, M.A. Influence of the anode materials on the electrochemical oxidation efficiency. Application to oxidative degradation of the pharmaceutical amoxicillin. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 262, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oaks, J.L.; Gilbert, M.; Virani, M.Z.; Watson, R.T.; Meteyer, C.U.; Rideout, B.A.; Shivaprasad, H.; Ahmed, S.; Chaudhry, M.J.I.; Arshad, M. Diclofenac residues as the cause of vulture population decline in Pakistan. Nature 2004, 427, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barışçı, S.; Turkay, O.; Ulusoy, E.; Soydemir, G.; Seker, M.G.; Dimoglo, A. Electrochemical treatment of anti-cancer drug carboplatin on mixed-metal oxides and boron doped diamond electrodes: Density functional theory modelling and toxicity evaluation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 344, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Ashtoukhy, E.-S.; Amin, N.; Abdelwahab, O. Treatment of paper mill effluents in a batch-stirred electrochemical tank reactor. Chem. Eng. J. 2009, 146, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Jin, T.; Hu, Z.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, M. TiO2-NTs/SnO2-Sb anode for efficient electrocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants: Effect of TiO2-NTs architecture. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2013, 102, 180–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Huang, Z.-H.; Lim, T.-T. Recent development of mixed metal oxide anodes for electrochemical oxidation of organic pollutants in water. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2014, 480, 58–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Zhou, J.; Meng, X.; Feng, D.; Wu, C.; Chen, J. Electrochemical oxidation of cinnamic acid with Mo modified PbO2 electrode: Electrode characterization, kinetics and degradation pathway. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 289, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Xing, J.; Chen, D.; Jin, D.; Shen, J. Electrochemical degradation of Musk ketone in aqueous solutions using a novel porous Ti/SnO2-Sb2O3/PbO2 electrodes. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2016, 775, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, R.; Meng, X.; Sun, P.; Niu, J.; Jiang, W.; Bottomley, L.; Li, D.; Chen, Y.; Crittenden, J. Electrochemical oxidation of ofloxacin using a TiO2-based SnO2-Sb/polytetrafluoroethylene resin-PbO2 electrode: Reaction kinetics and mass transfer impact. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2017, 203, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yu, Y.; Yin, L.; Niu, J.; Hou, L.-A. Insights of ibuprofen electro-oxidation on metal-oxide-coated Ti anodes: Kinetics, energy consumption and reaction mechanisms. Chemosphere 2016, 163, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brillas, E.; Martínez-Huitle, C.A. Decontamination of wastewaters containing synthetic organic dyes by electrochemical methods. An updated review. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2015, 166, 603–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alighardashi, A.; Aghta, R.S.; Ebrahimzadeh, H. Improvement of Carbamazepine Degradation by a Three-Dimensional Electrochemical (3-EC) Process. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 12, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Wen, X.-H.; Huang, X. Enhanced removal performance of estriol by a three-dimensional electrode reactor. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 327, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Chen, J.; Fu, Z.; Niu, J. Bicarbonate enhancing electrochemical degradation of antiviral drug lamivudine in aqueous solution. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2019, 848, 113314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachter, N.; Aquino, J.M.; Denadai, M.; Barreiro, J.C.; Silva, A.J.; Cass, Q.B.; Rocha-Filho, R.C.; Bocchi, N. Optimization of the electrochemical degradation process of the antibiotic ciprofloxacin using a double-sided β-PbO2 anode in a flow reactor: Kinetics, identification of oxidation intermediates and toxicity evaluation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 4438–4449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yin, L.; Xu, Z.; Niu, J.; Hou, L.-A. Electrochemical degradation of enrofloxacin by lead dioxide anode: Kinetics, mechanism and toxicity evaluation. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 326, 911–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Guo, S.; Yan, G.; Chen, C.; Jiang, X. Electrochemical pretreatment of heavy oil refinery wastewater using a three-dimensional electrode reactor. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 8615–8620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuny, A.; Font, J.; Fabregat, A. Wet air oxidation of phenol using active carbon as catalyst. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 1998, 19, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Duan, P.; Lei, J.; Sun, Z.; Hu, X. Fabrication of Ti/TiO2/SnO2-Sb-Cu electrode for enhancing electrochemical degradation of ceftazidime in aqueous solution. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2019, 847, 113231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, P.; Hu, X.; Ji, Z.; Yang, X.; Sun, Z. Enhanced oxidation potential of Ti/SnO2-Cu electrode for electrochemical degradation of low-concentration ceftazidime in aqueous solution: Performance and degradation pathway. Chemosphere 2018, 212, 594–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turkay, O.; Barisci, S.; Ulusoy, E.; Dimoglo, A. Electrochemical Reduction of X-ray Contrast Iohexol at Mixed Metal Oxide Electrodes: Process Optimization and By-product Identification. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2018, 229, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, G. Fabrication and application of Ti/BDD for wastewater treatment. Synth. Diam. Film. Prep. Electrochem. Charact. Appl. 2011, 353–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Huang, W.; Chen, R.; Zhang, W.; Lin, H.; Li, H. Anodic oxidation of aspirin on PbO2, BDD and porous Ti/BDD electrodes: Mechanism, kinetics and utilization rate. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2015, 156, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirés, I.; Oturan, N.; Oturan, M.A. Electrochemical degradation of β-blockers. Studies on single and multicomponent synthetic aqueous solutions. Water Res. 2010, 44, 3109–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandavelu, V.; Yoshihara, S.; Kumaravel, M.; Murugananthan, M. Anodic oxidation of isothiazolin-3-ones in aqueous medium by using boron-doped diamond electrode. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2016, 69, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugananthan, M.; Latha, S.; Raju, G.B.; Yoshihara, S. Anodic oxidation of ketoprofen—An anti-inflammatory drug using boron doped diamond and platinum electrodes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 180, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocenschi, R.F.; Rocha-Filho, R.C.; Bocchi, N.; Biaggio, S.R. Electrochemical degradation of estrone using a boron-doped diamond anode in a filter-press reactor. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 197, 186–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coledam, D.A.; Pupo, M.M.; Silva, B.F.; Silva, A.J.; Eguiluz, K.I.; Salazar-Banda, G.R.; Aquino, J.M. Electrochemical mineralization of cephalexin using a conductive diamond anode: A mechanistic and toxicity investigation. Chemosphere 2017, 168, 638–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barışçı, S.; Turkay, O.; Ulusoy, E.; Şeker, M.G.; Yüksel, E.; Dimoglo, A. Electro-oxidation of cytostatic drugs: Experimental and theoretical identification of by-products and evaluation of ecotoxicological effects. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 334, 1820–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Gul, S.; Steter, J.R.; Miwa, D.W.; Motheo, A.J. Route of electrochemical oxidation of the antibiotic sulfamethoxazole on a mixed oxide anode. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2015, 22, 15004–15015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Li, D.; Wan, J.; Yu, X. Preparation and electrochemical property of TiO2/Nano-graphite composite anode for electro-catalytic degradation of ceftriaxone sodium. Electrochim. Acta 2015, 180, 957–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Wu, J.; Zhang, H. Degradation of clofibric acid in aqueous solution by an EC/Fe3+/PMS process. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 244, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifuna, F.W.; Orata, F.; Okello, V.; Jemutai-Kimosop, S. Comparative studies in electrochemical degradation of sulfamethoxazole and diclofenac in water by using various electrodes and phosphate and sulfate supporting electrolytes. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A 2016, 51, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, X.; Xiao, S.; Song, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zeng, P. Treatment of simulated berberine wastewater by electrochemical process with Pt/Ti anode. Environ. Earth Sci. 2015, 73, 4957–4966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, P.; Yang, X.; Huang, G.; Wei, J.; Sun, Z.; Hu, X. La2O3-CuO2/CNTs electrode with excellent electrocatalytic oxidation ability for ceftazidime removal from aqueous solution. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2019, 569, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, P.; Gao, S.; Li, X.; Sun, Z.; Hu, X. Preparation of CeO2-ZrO2 and titanium dioxide coated carbon nanotube electrode for electrochemical degradation of ceftazidime from aqueous solution. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2019, 841, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, E.; Stożek, S.; Patiño, Y.; Ordóñez, S. Electrochemical degradation of naproxen from water by anodic oxidation with multiwall carbon nanotubes glassy carbon electrode. Water Sci. Technol. Water Treat. 2019, 79, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiańska, A.; Ofiarska, A.; Fiszka-Borzyszkowska, A.; Stepnowski, P.; Siedlecka, E.M. Electrodegradation of ifosfamide and cyclophosphamide at BDD electrode: Decomposition pathway and its kinetics. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 276, 274–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, J.R.; Muñoz-Peña, M.J.; González, T.; Palo, P.; Cuerda-Correa, E.M. Parabens abatement from surface waters by electrochemical advanced oxidation with boron doped diamond anodes. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 20315–20330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabaaoui, N.; Allagui, M.S. Anodic oxidation of salicylic acid on BDD electrode: Variable effects and mechanisms of degradation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 243, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indermuhle, C.; Martin de Vidales, M.J.; Saez, C.; Robles, J.; Canizares, P.; Garcia-Reyes, J.F.; Molina-Diaz, A.; Comninellis, C.; Rodrigo, M.A. Degradation of caffeine by conductive diamond electrochemical oxidation. Chemosphere 2013, 93, 1720–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambuludi, S.L.; Panizza, M.; Oturan, N.; Ozcan, A.; Oturan, M.A. Kinetic behavior of anti-inflammatory drug ibuprofen in aqueous medium during its degradation by electrochemical advanced oxidation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2013, 20, 2381–2389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Silva Duarte, J.L.; Solano, A.M.S.; Arguelho, M.L.; Tonholo, J.; Martínez-Huitle, C.A.; e Silva, C.L.d.P. Evaluation of treatment of effluents contaminated with rifampicin by Fenton, electrochemical and associated processes. J. Water Process Eng. 2018, 22, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coledam, D.A.; Aquino, J.M.; Silva, B.F.; Silva, A.J.; Rocha-Filho, R.C. Electrochemical mineralization of norfloxacin using distinct boron-doped diamond anodes in a filter-press reactor, with investigations of toxicity and oxidation by-products. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 213, 856–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steter, J.R.; Rocha, R.S.; Dionísio, D.; Lanza, M.R.; Motheo, A.J. Electrochemical oxidation route of methyl paraben on a boron-doped diamond anode. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 117, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabiańska, A.; Białk-Bielińska, A.; Stepnowski, P.; Stolte, S.; Siedlecka, E.M. Electrochemical degradation of sulfonamides at BDD electrode: Kinetics, reaction pathway and eco-toxicity evaluation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 280, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinzila, C.; Monteiro, N.; Pacheco, M.; Ciríaco, L.; Siminiceanu, I.; Lopes, A. Degradation of tetracycline at a boron-doped diamond anode: Influence of initial pH, applied current intensity and electrolyte. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 8457–8465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidar, M.; Dirany, A.; Sirés, I.; Oturan, N.; Oturan, M.A. Electrochemical degradation of the antibiotic sulfachloropyridazine by hydroxyl radicals generated at a BDD anode. Chemosphere 2013, 91, 1304–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, T.; Domínguez, J.R.; Palo, P.; Sánchez-Martín, J. Conductive-diamond electrochemical advanced oxidation of naproxen in aqueous solution: Optimizing the process. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011, 86, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, J.R.; González, T.; Palo, P.; Sánchez-Martín, J. Electrochemical advanced oxidation of carbamazepine on boron-doped diamond anodes. Influence of operating variables. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 49, 8353–8359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, P.; Zheng, H.; Zhao, C.; Xiao, X.; Xu, Y.; Sun, W.; Wu, H.; Ren, M. Electrochemical treatment of chloramphenicol using Ti-Sn/γ-Al2O3 particle electrodes with a three-dimensional reactor. Chem. Eng. J. 2017, 308, 1233–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Yu, Y.; Sun, Z. Preparation and characterization of cerium-doped multiwalled carbon nanotubes electrode for the electrochemical degradation of low-concentration ceftazidime in aqueous solutions. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 199, 80–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhou, M.; Oturan, N.; Li, Y.; Su, P.; Oturan, M.A. Enhanced activation of hydrogen peroxide using nitrogen doped graphene for effective removal of herbicide 2, 4-D from water by iron-free electrochemical advanced oxidation. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 297, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qaim, F.F.; Mussa, Z.H.; Othman, M.R.; Abdullah, M.P. Removal of caffeine from aqueous solution by indirect electrochemical oxidation using a graphite-PVC composite electrode: A role of hypochlorite ion as an oxidising agent. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 300, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frontistis, Z.; Antonopoulou, M.; Yazirdagi, M.; Kilinc, Z.; Konstantinou, I.; Katsaounis, A.; Mantzavinos, D. Boron-doped diamond electrooxidation of ethyl paraben: The effect of electrolyte on by-products distribution and mechanisms. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 195, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palo, P.; Domínguez, J.R.; González, T.; Sánchez-Martin, J.; Cuerda-Correa, E.M. Feasibility of electrochemical degradation of pharmaceutical pollutants in different aqueous matrices: Optimization through design of experiments. J. Environ. Sci. Health Part A 2014, 49, 843–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vidales, M.J.M.; Millán, M.; Sáez, C.; Pérez, J.F.; Rodrigo, M.A.; Cañizares, P. Conductive diamond electrochemical oxidation of caffeine-intensified biologically treated urban wastewater. Chemosphere 2015, 136, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaghdoudi, M.; Fourcade, F.; Soutrel, I.; Floner, D.; Amrane, A.; Maghraoui-Meherzi, H.; Geneste, F. Direct and indirect electrochemical reduction prior to a biological treatment for dimetridazole removal. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 335, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkheiri, D.; Fourcade, F.; Geneste, F.; Floner, D.; Aït-Amar, H.; Amrane, A. Feasibility of an electrochemical pre-treatment prior to a biological treatment for tetracycline removal. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2011, 83, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahiaoui, I.; Aissani-Benissad, F.; Fourcade, F.; Amrane, A. Removal of tetracycline hydrochloride from water based on direct anodic oxidation (Pb/PbO2 electrode) coupled to activated sludge culture. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 221, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Nava, O.; Ramírez-Saad, H.; Loera, O.; González, I. Evaluation of the simultaneous removal of recalcitrant drugs (bezafibrate, gemfibrozil, indomethacin and sulfamethoxazole) and biodegradable organic matter from synthetic wastewater by electro-oxidation coupled with a biological system. Environ. Technol. 2016, 37, 2964–2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Gómez, C.; Drogui, P.; Seyhi, B.; Gortáres-Moroyoqui, P.; Buelna, G.; Estrada-Alvgarado, M.I.; Álvarez, L.H. Combined membrane bioreactor and electrochemical oxidation using Ti/PbO2 anode for the removal of carbamazepine. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2016, 64, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouarda, Y.; Tiwari, B.; Azais, A.; Vaudreuil, M.A.; Ndiaye, S.D.; Drogui, P.; Tyagi, R.D.; Sauve, S.; Desrosiers, M.; Buelna, G.; et al. Synthetic hospital wastewater treatment by coupling submerged membrane bioreactor and electrochemical advanced oxidation process: Kinetic study and toxicity assessment. Chemosphere 2018, 193, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensano, B.M.B.; Borea, L.; Naddeo, V.; Belgiorno, V.; de Luna, M.D.G.; Balakrishnan, M.; Ballesteros, F.C., Jr. Applicability of the electrocoagulation process in treating real municipal wastewater containing pharmaceutical active compounds. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 361, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borea, L.; Ensano, B.M.B.; Hasan, S.W.; Balakrishnan, M.; Belgiorno, V.; de Luna, M.D.G.; Ballesteros, F.C.; Naddeo, V. Are pharmaceuticals removal and membrane fouling in electromembrane bioreactor affected by current density? Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 692, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

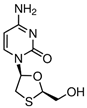

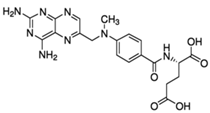

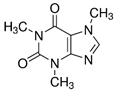

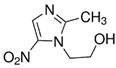

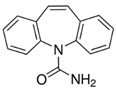

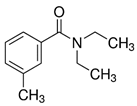

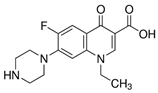

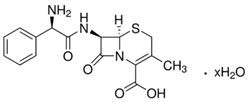

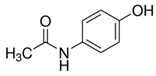

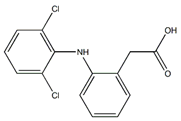

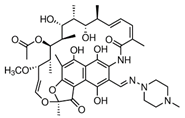

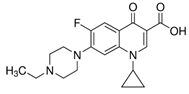

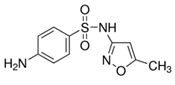

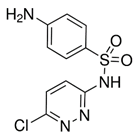

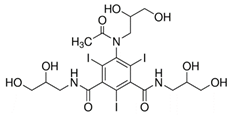

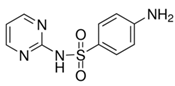

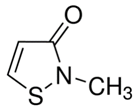

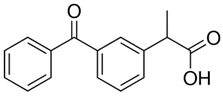

| Compounds (CAS) Classification | Structure | Compounds (CAS) Classification | Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin (50-78-2) Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) |  | Lamivudine (134678-17-4) Antivirals |  |

| Atenolol (29122-68-7) Beta-blockers |  | Levodopa (59-92-7) Antiparkinson Agents |  |

| Berberine (2086-83-1) Antibiotics |  | Methotrexate (59-05-2) Antineoplastics |  |

| Caffeine (58-08-2) Stimulant |  | Metronidazole (443-48-1) Antibiotics |  |

| Carbamazepine (298-46-4) Anticonvulsants |  | Musk ketone (81-14-1) Fragrances |  |

| Carboplatin (41575-94-4) Antineoplastics |  | Naproxen (22204-53-1) NSAIDs |  |

| Ceftazidime (78439-06-2) Antibiotics |  | N,N-diethyl-m Toluamide (134-62-3) Insect repellents |  |

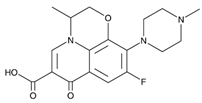

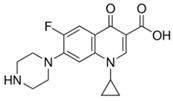

| Ceftriaxone sodium (104376-79-6) Antibiotics |  | Norfloxacin (70458-96-7) Antibiotics |  |

| Cephalexin (15686-71-2) Antibiotics |  | Ofloxacin (82419-36-1) Antibiotics |  |

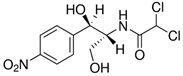

| Chloramphenicol (56-75-7) Antibiotics |  | Omeprazole (73590-58-6) Antibiotics |  |

| Ciprofloxacin (85721-33-1) Antibiotics |  | Methyl Paraben (99-76-3) Preservatives |  |

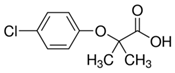

| Clofibric acid (882-09-7) Blood lipid regulators |  | Paracetamol (103-90-2) NSAIDs |  |

| Diclofenac (15307-86-5) NSAIDs |  | Rifampicin (13292-46-1) Antibiotics |  |

| Enrofloxacin (93106-60-6) Antibiotics |  | Salicylic acid (69-72-7) NSAIDs |  |

| Estrone (53-16-7) Hormones |  | Sulfamethoxazole (723-46-6) Antibiotics |  |

| Ibuprofen (15687-27-1) NSAIDs |  | Sulfachloropyrida-zine (80-32-0) Antibiotics |  |

| Iohexol (66108-95-0) Radiological Non-Ionic Contrast Media |  | Sulfadiazine (68-35-9) Antibiotics |  |

| 2-methyl-4-isothiazolin-3-one (2682-20-4) Preservatives |  | Tetracycline (60-54-8) Antibiotics |  |

| Ketoprofen (22071-15-4) NSAIDs |  |

| Compounds | Initial Concentration | Treatment Processes | Removal Efficiency (%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspirin | 930 ng/L | Modified Bardenpho process | 92 | [19] |

| Atenolol | 255 ng/L | Grit tanks|primary sedimentation|bioreactor|clarifiers | 47.1 | [19] |

| 1197 ng/L | Pretreatment|primary (settling)|secondary activated sludge (AS) | 14.4 | [20] | |

| 2.3 ± 2.0 | Grit removal|primary clarifier|denitrification|nitrification|second clarifier | 84 | [21] | |

| Berberine | 75.0–375.0 mg/L | Upflow anaerobic sludge blanket (UASB)–membrane bioreactor (MBR) | 99 | [22] |

| Caffeine | 82 ± 36 μg/L | Grit removal|primary clarifier|denitrification|nitrification|second clarifier | 99.7 | [21] |

| 22,849 ng/L | Anaerobic/Anoxic/Oxic (A2O) | 94.9 | [23] | |

| Carbamazepine | 208–416 ng/L | A series of different waste stabilization ponds | 73 | [24] |

| 129 ng/L | Pretreatment|primary (settling)|secondary AS | 9.5 | [20] | |

| 2.0 ± 1.3 μg/L | Grit removal|primary clarifier|denitrification|nitrification|second clarifier | 0 | [21] | |

| Carboplatin | 4.7 to 145 μg/L | Adsorption to AS | 70% | [25] |

| Ceftazidime | 40 mg/L | Coupling ultraviolet (UV)|algae-algae treatment | 97.26 | [26] |

| Ceftriaxone | 14 µg/L | AS process | <1 | [27] |

| Cephalexin | 4.6 mg/L | Grit channels|primary clarifies|conventional AS|Final settling | 87 | [28] |

| Chloramphenicol | 206 ± 56 ng/L | Preliminary screening|primary sedimentation|conventional AS treatment | >70 | [29] |

| 31 ± 16 ng/L | Screen|primary clarifier|AS system for denitrification and nitrification | 50 | [30] | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 2200 ng/L | Grit channels|primary clarifies|conventional AS | −88.6 | [31] |

| 5524 ng/L | Pretreatment|primary (settling)|secondary AS | 57 | [20] | |

| Clofibric acid | 2 mg/L | Aerobic sequencing batch reactors (SBRs) with mixed microbial cultures | 51 | [32] |

| 0.25 ± 0.09 μg/L | Grit removal|primary clarifier|denitrification|nitrification|second clarifier | 52 | [21] | |

| 26 ng/L | Pretreatment|primary (settling)|secondary AS | 54.2 | [20] | |

| Diclofenac | 20–70 mg/L | Primary treatment|Orbal oxidation ditch|UV disinfection | 10–60 | [33] |

| 2.0 ± 1.5 μg/L | Grit removal|primary clarifier|denitrification|nitrification|second clarifier | 96 | [21] | |

| 232 ng/L | Pretreatment|primary (settling)|secondary AS | 5 | [20] | |

| Enrofloxacin | 9–170 ng/L | Conventional AS|UV disinfection | 65 | [34] |

| Estrone | 57 ng/L | Grit channels|primary clarifies|conventional AS | 93.7 | [31] |

| Ibuprofen | 4500 ng/L | Grit channels|primary clarifies|conventional AS | 99.7 | [31] |

| 3.4 ± 1.7 μg/L | Grit removal|primary clarifier|denitrification|nitrification|second clarifier | 96 | [21] | |

| 2687 ng/L | Pretreatment|primary (settling)|secondary AS | 95 | [20] | |

| Iohexol | 9.0 ± 2.0 μg/L | Grit removal|primary clarifier|denitrification|nitrification|second clarifier | 89 | [21] |

| 2-methyl-4-isothiazolin-3-one | 1–3 mg/L | Aerobic process | 80–100 | [35] |

| Ketoprofen | 441 ng/L | Anaerobic/Anoxic/Oxic (A2O) | 11.2 | [23] |

| Lamivudine | 210 ± 13 ng/L | Screen|aerated grit-removal|primary clarifier|nitrification/denitrification | >76 | [36] |

| Methotrexate | 7.30–55.8 ng/L | Pretreatment|primary (settling)|secondary AS | 100 | [20] |

| Metronidazole | 90 ng/L | Anaerobic/Anoxic/Oxic (A2O) | 38.7 | [23] |

| Musk ketone | 0.640 ± 0.395 μg/L | Primary gravitational settling|AS | 91.0 ± 5.2 | [37] |

| Naproxen | 3000 ng/L | Grit channels|primary clarifies|conventional AS | 96.2 | [31] |

| 2363 ng/L | Pretreatment|primary (settling)|secondary AS | 60.9 | [20] | |

| DEET | 503 ng/L | Primary|secondary treatment with AS | 19.2–46.2 | [38] |

| Norfloxacin | 229 ± 42 ng/L | Screen|primary clarifier|AS system for denitrification and nitrification | 66 | [30] |

| Ofloxacin | 2100 ng/L | Grit channels|primary clarifies|conventional AS | 124.2 | [31] |

| 2275 ng/L | Pretreatment|primary (settling)|secondary AS | 64.1 | [20] | |

| Omeprazole | 365 ng/L | Pretreatment|primary (settling)|secondary AS | 8.5 | [20] |

| Methyl Paraben | 801 ng/L | Conventional biological treatment with P and N removal | 100 | [39] |

| Paracetamol | 218,000 ng/L | Modified Bardenpho process | 99 | [19] |

| 23,202 ng/L | Pretreatment|primary (settling)|secondary AS | 100 | [20] | |

| Rifampicin | 0–31 ng/L | Secondary treatment process: AS, biological filtration oxygenated reactor, anoxic/oxic (A/O), cyclic AS technology (CAST), and A2O | 0–100 | [40] |

| Salicylic acid | 5.866 μg/L | Primary|secondary treatment: trickling filter beds|final clarification. | >98 | [41] |

| Sulfamethoxazole | 7400 ng/L | Grit channels|primary clarifies|conventional AS | −35.8 | [31] |

| 0.82 ± 0.23 μg/L | Grit removal|primary clarifier|denitrification|nitrification|second clarifier | 24 | [21] | |

| 524 ng/L | Pretreatment|primary (settling)|secondary AS | 31.2 | [20] | |

| 118 ± 17 ng/L | Screen|primary clarifier|AS system for denitrification and nitrification | 64 | [30] | |

| Sulfachloropyridazine | 0.19 μg/L | Conventional AS | 62 | [42] |

| Sulfadiazine | 72 ± 22 ng/L | Screen|primary clarifier|AS system for denitrification and nitrification | 50 | [30] |

| Tetracycline | 257 ± 176 ng/L | Preliminary screening|primary sedimentation|conventional AS treatment | 69 | [29] |

| Analytical Methods | PPCPs |

|---|---|

| GC-MS | Ciprofloxacin, Chloramphenicol, Methyl paraben |

| HPLC | Lamivudine, Ceftazidime, Carboplatin, Aspirin, Cephalexin, Musk ketone, Norfloxacin, Ceftriaxone sodium, Levodopa, N,N-diethyl-m-Toluamide (DEET) |

| HPLC-DAD | Acetaminophen, Diclofenac, Sulfamethoxazole, Chloramphenicol, Ofloxacin, Berberine, Tetracycline |

| HPLC-UV/HPLC-UV vis/UV-vis | Ciprofloxacin, Rifampicin, Carbamazepine, Caffeine, Enrofloxacin, Sulfamethoxazole, Diclofenac, Isothdiazolin-3-ones, Metronidazole, Estrone, Paracetamol, Diclofenac, Methyl paraben, Clofibric acid, Sulfonamides |

| HPLC-HR-MS/HPLC-MS/HPLC-MS-MS | Carbamazepine, Iohexol, Ceftazidime, Methotrexate, Ibuprofen, Clofibric acid |

| HPLC-PDA | Atenolol, Paracetamol, Salicylic acid, Parabens, Sulfachloropyridazine, Omeprazole, Ibuprofen, Naproxen, Carbamazepine |

| PPCPs | Initial C | Electrolyte | j/mA cm−2 | Reactors/Operational Parameters | Electrodes | pH | Reaction Time (min) | Removal (%) | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anode | Cathode | |||||||||

| Lamivudine | 5 mg/L | 20 mM Na2SO4 | ≥10 | Undivided cell, V 450 mL, current density (j) (6–14 mA cm−2) | Ti/SnO2-Sb/Ce-PbO2; 7 cm × 10 cm × 1 mm | Stainless steel (SS); 7 cm × 10 cm × 1 mm, gap 2 cm | 3–11 | 240 | 70 (TOC) | [70] |

| Ciprofloxacin | 50 mg/L | 0.1 mol/L Na2SO4 | 30 | Filter-press flow reactor; pH (3, 7, and 10), flow rate (qV = 2.5, 4.5, and 6.5 L min−1), j (6.6, 20, and 30 mA cm−2), and T = 10, 25, and 40 °C | Ti-Pt/β- PbO2; 3.1 cm × 2.0 cm, 3.1 cm × 2.7 cm | AISI 304 SS plate | 10 | 120 | 100 | [71] |

| Ofloxacin | 20 mg/L | Na2SO4 | 30 | Differential column batch reactor, fluid velocity: 0.003 and 0.048 m/s, detention time: 10.3–0.54 min. | TiO2-based SnO2-Sb/FR- PbO2; 2 cm × 5 cm | SS foil; Same shape and size, gap 0.5 and 3 cm | 6.25 | 90 | 99.00 | [65] |

| Enrofloxacin | 10 mg/L | 20 mM Na2SO4 | 8 | Undivided electrolytic cell, V 30 mL, j (2–10 mA/cm2), pH (∼3–11) | Ti/SnO2-Sb/La- PbO2; 25 cm2 | Ti; Same area; gap 5 mm | 3–11 | 30 | 95.1 (TOC) | [72] |

| Musk ketone | 50 mg/L | 0.06 mol/L Na2SO4 | 40 | Cylindrical single compartment cell, V 100 ml, stirring rate 800 rmin−1, j (10–50 mA cm−2), pH (3–11) | Ti/SnO2-Sb2O3/PbO2; 1 cm × 1 cm | Stainless copper foil; (2 cm × 2 cm), gap 1.5 cm | 7 | 120 | 99.93 | [64] |

| Levodopa | 100 mg/L | 0.1 mol/L Na2SO4 | 50 | Electrochemical system, V 250 mL, j (15–70 mA cm−2) | La–Gd– PbO2; 12 cm × 2 cm, thickness: 1 mm, 14 cm2 | Ti; The same area; gap 4 cm | 5.9 | 120 | 100.00 | [55] |

| PPCPs | Initial C | Electrolyte | j/mA cm−2 | Reactors/Operational Parameters | Electrodes | pH | Reaction Time (min) | Removal (%) | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anode | Cathode | |||||||||

| Ceftazidime | 5 mg/L | 1 g/L Na2SO4 | 1.25 | V reactor and electrolytic wastewater was 150 mL and 120 mL, respectively | Ti/TiO2/SnO2-Sb-Cu; (50 mm × 30 mm × 2 mm) | Pt wire; gap 4 cm | 6 | - | 97.65 | [75] |

| Iohexol | 0.525 mg/L | 0.1 M Na2SO4 | 38.1–45 | Batch experiments, V 350 mL, pH 7.2, iohexol concentration 0.525 mg/L; j = 15, 30, and 45 mA/cm2; pH (4.0, 7.0 ± 02, and 9.0) | Ti/RuO2; 25 cm2 | SS; 0.5-mm gap | 7.1 | 19.8–30 | >90 | [77] |

| Carboplatin | 0.5 mg/L | 0.1 M Na2SO4 | 30 | One-compartment cell 350 mL; pH range 4–9; j = 15, 30 and 45 mA/cm−2; | Ti/RuO2; 25 cm2 | SS plate; 25 cm2 gap 0.5 cm | 7 | 5 | 100.00 | [59] |

| Methotrexate | 0.5 mg/L | 200 mg/L Na2SO4 | 30 | One-compartment cell, V 350 mL, Na2SO4 (100, 200, 300 mg/L), pH range of 4–9; j = 15, 30 and 45 mA cm−2 | Ti/IrO2-RuO2; 25 cm2 | SS plate; 0.5 cm gap | 7 | 5 | 95.00 | [85] |

| Estriol | 1000 μg/L | 0.1M Na2SO4 | 20 | Batch 3D electrolysis, an undivided rectangular reactor, V 300 mL, filled with approximately 50 g granular graphite particles and 70 g glass beads | Ti/IrO2-RuO2; 5 × 10 cm | Ti; 5 × 10 cm; gap could be adjusted | 3–7 | 50 | 80.00 | [69] |

| Sulfamethoxazole | 200 mg/L | 0.1 mol/L NaCl | ≥20 | Single compartment filter press-type flow cell reactor, flow rate: 425 mL/min | Ti/Ru0.3Ti0.7O; 14 cm2 | Ti plate; The same geometric area | 3 | 30 | >98 | [86] |

| Ceftriaxone sodium | 10 mg/L | 0.1 mol/L Na2SO4 | (The external potential of +2.0 V) | A cylindrical glass reactor made, fused and sealed at one end | TiO2(40)/Nano-G | Titanium mesh; gap 2 cm | - | 120 | 97.70 | [87] |

| Clofibric acid | 50 mg/L | 50mM Na2SO4 | 33.6 | 250 mL undivided glass beaker containing 200 mL solution, T constant at 20 °C, constant current | Plate mixed metal oxide (DSA, Ti/RuO2–IrO2); 5.0 cm × 11.9 cm | SS; Same dimension; gap 4.0 cm | 4 | 180 | 64.70 (TOC) | [88] |

| PPCPs | Initial C | Electrolyte | j/mA cm−2 | Reactors/Operational Parameters | Electrodes | pH | Reaction Time (min) | Removal (%) | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anode | Cathode | |||||||||

| Atenolol | 0.19 mmol/L | 14 mmol/L Na2SO4 | 30 | Double-jacket glass, one-compartment flow filter-press reactor, V 0.002 m3, pH: 3 and 10, flow rate 3.33 × 10−5 m3 s−1, j (5, 10, 20 and 30 mAcm−2), T = 25 °C | Nb/BDD500; 0.01 m2 | AISI 304L; Gap 0.02 m | 10 | 120 | 100.00 | [48] |

| Rifampicin | 200 mg/L | 0.5 mol/L Na2SO4 | 90 | 250-mL undivided open cell, equipped with magnetic stirring at 30 °C | BDD; 3.0 × 2.5 cm | Ti/Ru0.3Ti0.7O2; 4.0 × 4.0 cm | 3 | 180 | 95.00 | [99] |

| Norfloxacin | 100 mg/L | 0.1 mol/L Na2SO4 | 10 | One-compartment filter-press flow reactor, pH (3, 7, 10, and without specific control), j (10, 20, and 30 mA cm−2), T (10, 25, and 40 °C) | BDD; Thickness of 2.9 μm | SS; area of 3.54 cm × 6.71 cm | not pH depen-dent | 300 | 100.00 | [100] |

| Estrone | 500 μg/L | 0.1 mol/L Na2SO4 | 10 | A filter-press electrochemical reactor, 0.5L solution, flow rate (2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, and 7.0 L/min), j (5, 10, and 25 mA cm−2), pH (3.0, 7.0, and 10.0) | BDD; each face was 2.5 cm × 3.0 cm 15 cm2 | SS; (3.0 cm × 4.0 cm) | <=7 | 30 | 98.00 | [83] |

| Paracetamol Diclofenac | 50 mg/L, 100 mg/L | 0.05 M Na2SO4 | 1.56–6.25 | 4L undivided filter flow press reactor, j (1.56 to 6.25 mAcm−2), flow rate kept constant at 2 L/min | BDD; 64 cm2 | SS; Gap 2 cm | 3 | 60 | 50.00 (TOC) | [50] |

| Methyl paraben | 100 mg/L | 0.05 mol/L K2SO4 | 10.8 | One-compartment pyrex cell (400 mL) operated at 25 ± 1 °C in batch mode, j (1.35 to 21.6 mA cm−2) | BDD; 9.68 cm−2 | Titanium foil; The same area | 5.7 | 300 | 100.00 | [101] |

| Sulfonamides | 50 mg/L | 6.1 g/L Na2SO4 | 15 | Undivided electrolytic cell, V 100 mL, pH (from 2.0 to 7.4), T (from 25 to 60 °C), and j (from 0.05 to 15 mA cm−2) | Si/BDD; 10 cm2 | SS; Gap 1cm | 6.4 | 180 | 92.00 | [102] |

| Tetracycline | 100 mg/L | 5 g/L Na2SO4 or NaCl | 25 to 300 A m−2 | Up-flow electrochemical cell, 20 cm3, batch mode with recirculation; pH (2 to 12), j (25 to 300 A m−2) | BDD; 20 cm2 | SS; Gap 1 cm | 5.6 | 30 min | 100.00 | [103] |

| Sulfachloropy-ridazine | 0.2 mM | 0.05 M Na2SO4 | 350 mA | An open, cylindrical and undivided glass cell 250 mL with magnetic stirring | BDD; 25 cm2 | Carbon-felt; 77 cm2 (14.0 cm × 5.5 cm) | 4.5 | 8h | 95.00 | [104] |

| Omeprazole | 169 mg/L | 0.05 Na2SO4 | 100 | Undivided and cylindrical glass cell of 150 mL, with a double jacket, j = 33.3–150 mA cm−2, T = 35 °C, stirred with 800 rpm | BDD; 3 cm2 | Carbon-PTFE air-diffusion; Gap 1 cm | 7 | 360 | 78.00 (TOC) | [54] |

| Ibuprofen | 0.2 mM | 0.05 M Na2SO4 | 50–500 mA | Cylindrical, open, one-compartment cell 200 mL, at T (20 ± 2 °C) | BDD; 25 cm2 | Carbon-felt; 14 cm×5 cm each side, 0.5 cm width | 3 | 480 | >96 (TOC) | [98] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dao, K.C.; Yang, C.-C.; Chen, K.-F.; Tsai, Y.-P. Recent Trends in Removal Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products by Electrochemical Oxidation and Combined Systems. Water 2020, 12, 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12041043

Dao KC, Yang C-C, Chen K-F, Tsai Y-P. Recent Trends in Removal Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products by Electrochemical Oxidation and Combined Systems. Water. 2020; 12(4):1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12041043

Chicago/Turabian StyleDao, Khanh Chau, Chih-Chi Yang, Ku-Fan Chen, and Yung-Pin Tsai. 2020. "Recent Trends in Removal Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products by Electrochemical Oxidation and Combined Systems" Water 12, no. 4: 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12041043

APA StyleDao, K. C., Yang, C.-C., Chen, K.-F., & Tsai, Y.-P. (2020). Recent Trends in Removal Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products by Electrochemical Oxidation and Combined Systems. Water, 12(4), 1043. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12041043