1. Introduction

“

Xmux’bal yuam nimla ha” or “the life of the river will be desecrated/violated”. This phrase surfaced many times during the conversations, meetings and focus groups in May 2014 with Maya Q’eqchi’ women, men and elders about the impact of the planned Xalalá hydroelectric dam on the Chixoy river, which the Guatemalan government was pushing forward. That same month, the then president and ex-general Otto Pérez Molina publicly defended this hydropower project, which would become the second largest dam in the country, as a “priority and of great need for the nation” [

1] because it would be crucial for Guatemala’s transformation of its energy matrix towards renewable energy. However, for the dam-threatened indigenous communities, the construction of this hydroelectric dam would create only destruction and loss, as “they will cut the veins of the earth” and “if they cut the river, it will dry up. It’s as if the blood in our body dries up, it’s similar to what happens to the water.” So, with this dam, “

loq’laj nimla ha Chixoy will suffer, will cry”, was repeatedly said by the Q’eqchi.

While much of the academic debate about extractive hydro development projects and their socio-political and environmental impacts has taken place in the fields of political ecology, water justice and water governance, in this article, I develop a critical legal anthropological approach to the analysis of human rights at risk and call for recognition of and a critical engagement with plurilegal water realities. It is internationally recognized that the construction of hydropower dams often seriously and irreversibly violates the human rights of the various social groups involved, in particular women and indigenous peoples, who may be disproportionately affected [

2]. In 2000, the World Commission on Dams, a global multi-stakeholder body endorsed by the World Bank and the World Conservation Union, established a comprehensive framework for the dam-building sector, which promotes the application of a “human rights approach”. This approach should provide “a more effective framework for the integration of economic, social and environmental dimensions in options assessment, planning and project cycles” [

2] (p. 206) and includes both recognition and assessment of rights put at risk during the management of hydropower projects across the design, decision-making and implementation phases [

2] (pp. 206–210). In a guide to a rights-based approach to dam-building, the international NGO Rivers International identified more than 20 civil, political, social, labor and cultural rights, and also specific human rights such as those of women, children and indigenous peoples, that could be threatened by these infrastructural constructions [

3]. These include human rights such as self-determination, the right to life, equality and non-discrimination, freedom of expression, the right to decent housing and children’s rights.

This article focuses on one of the key human rights put at risk by the construction of hydroelectric dams—the human right to water and sanitation—which “fundamentally changes the right to access and use water for people affected by dams, by flooding, draining, and/or changing the flow of the river on which they depend” [

3] (p. 9). Ten years ago, the United Nations (UN) General Assembly explicitly recognized the right to water and sanitation as a human right essential to the realization of all human rights and a right that the UN Human Rights Council confirmed is legally binding upon states to respect, protect and fulfil [

4]. This formally recognized the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights’ definition of the right to water as “the right of everyone to sufficient, safe, acceptable and physically accessible and affordable water for personal and domestic uses”, established in its General Comment No 15 of 2002 and derived from the right to an adequate standard of living (article 11) of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

Political ecologists have pointed out that the value of water is defined in economic terms and that the access to it protected by this human right is predominantly “understood and seen as organized through market mechanisms and the power of money, irrespective of social, human or ecological need” [

5]. Though, in line with the insightful reflection of legal anthropologist Sally Engle Merry that “while anthropologists like to destabilize existing categories, like gender and rights … lawyers want to clarify categories, define things and to be sure you know what you are talking about” [

6], this article focuses legal ethnographic attention on the human right to water within the context of the human rights risk assessment of extractive industries in indigenous territories. I argue that the human rights field should not take for granted what water is. Against the background of the interlocking challenges that global water conflicts, climate emergency, species extinctions, ecological devastation and also pandemics pose to the human species, I argue that it is necessary to destabilize the dominant Euro-Western legal concept of water as a commodity, a natural resource to be extracted and used for human consumption. There is an urgent need to reconceptualize human rights with ontologically different ways of understanding and relating to human-water-life through bottom-up co-theorizing in order to pave the way for human rights beyond the human.

This article is grounded in and draws on my long-term collaborative legal ethnographic work with Maya Q’eqchi’ communities living in the north-west of the Guatemalan Alta Verapaz department in academic and policy research projects, spanning almost 20 years, about the state-led violence and genocide during the 1970s and 1980s, transitional justice processes and the impact of hydroelectric dams. Over the course of these interrelated research projects, new and ever deeper theoretical and methodological research questions surfaced. At the same time, during my diverse human rights practitioner’s experiences, amongst others at the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in Ecuador, (from 2010 to 2013 I was responsible for the areas of indigenous and afro-descendants’ collective rights and transitional justice). I was confronted with the internal limits of the hegemonic human rights discourse and norms. My different personal paradigm shifts that unfolded during these years are beyond the scope of this article, but the process of understanding the complex Maya Q’eqchi’ ontological-legal concepts of human-water-life relations led me—a Global North-trained and -based white legal anthropologist—to realize that the “real-world law is intrinsically plural” [

7]. In 2002, during my first ethnographic encounter with Q’eqchi’ survivors of the State-led genocide, an old woman told me: “The

Tzuultaq’a is God because

yoyo, it lives”. As a young Belgian student of anthropology, I thought I was being told about a “belief”, one more myth among the many held by Mesoamerican indigenous peoples. Over the years of this empirical engagement, however, I learned from the Q’eqchi’ that the

Tzuultaq’a is, following Peruvian anthropologist Marisol de la Cadena, “not only” [

8] a belief in the Euro-Western significance of the word. It is much more:

Tzuultaq’a, which literally means Mountain-Valley, has an ontological status framing Maya Q’eqchi’ identity, being and relationship with their natural environment or what is increasingly conceptualized as the “no-human”, “more-than-human” or “other-than-human” in different fields of social science [

9,

10,

11]. In this article, I use the phrase “human-water-life” when referring to the Maya Q’eqchi’ way of conceptualizing water for, as will be discussed in depth in

Section 3, this captures the meaning of water’s interdependent relationship with human beings, in which its well-being is not centralized to the human.

Recently, some critical legal theory scholars within the field of international law have been embarking on a critical examination of the fact that “the human subject stands at the center of the juridical order as its only and true agent and beneficiary” [

12]. Moreover, a growing number of scholars and practitioners of international environmental law have recently begun to discuss the decentering of this anthropocentric dogma, shifting towards an eco-centric and ecosystem approach [

13]. However, even though these fields of international law, human rights and environment are increasingly engaging with historically marginalized and excluded epistemologies, such as indigenous legal concepts, I argue that they do not sufficiently engage with the ontological questions these water pluralities bring to the fore.

In fact, indigenous human-water-life relationships, such as those discussed regarding Maya Q’eqchi’, unveil competing political and legal water realities that interrogate key modern assumptions, which have organized dominant understandings of the modern world and everyday power relations affecting law, natural resources, development and territory. Indeed, it should be recognized that “reality is historically, culturally and materially located” [

14] and therefore “the world is not simply epistemologically complex. It is ontologically complex too” [

15]. In line with Canadian Métís anthropologist Zoe Todd, I therefore call on the human rights field to recognize these indigenous human-water-life relationships in the midst of extractive development projects as “concrete sites of political and legal exchange” [

16], which should inform a critical narrative that de-anthropocentralizes and decolonizes the core dogma of human rights.

This article is organized as follows: First, I describe the sociopolitical and economic research setting of the Guatemalan hydropower Xalalá dam project, in which collaborative legal ethnographic work was carried out over the course of different policy-related and academic research projects. I then interweave the complex ethnographic accounts of Q’eqchi’ human-water-life relationships, which suggest that water goes beyond the dominant conceptualization as water as a human right and a natural resource. I end by discussing several underexplored political and scientific areas of contestation that need to be addressed in order to engage critically with plurilegal water ontologies in international law and human rights scholarship.

3. Water Pluralities: Water beyond a Natural Resource and a Human Right

By interweaving the different ethnographic accounts resulting from my diverse research projects in this section, I will critically and empirically unpack not only the anthropocentric boundaries of the hegemonic human rights paradigm, but also some of the ontological differences between indigenous and Euro-Western legal conceptualizations about water, rivers, mountains and life. This complex multi-layered ethnographic landscape of the Xalalá water conflict, like many others in indigenous lands and territories around the world, raises fundamental challenges regarding the anthropocentric boundaries of the human rights paradigm. Further, as previously stated elsewhere:

They question dominant modern ontology culture/nature, mind/body, human/non-human, belief/reality divides. For indigenous peoples, the world is non-dual: Everything is one, interrelated and interdependent. There is no separation between the material, the cultural and the spiritual. In addition, everything lives and is sacred: Not just human beings, but also hills, caves, water, houses, plants and animals have agency [

35].

3.1. The Xalalá Dam, Another Nimla Rahilal or Deep Suffering and Pain

“The same thing happened to us in the ‘80s, when we wanted land, the war started. The same thing is going to happen now. INDE doesn’t make it clear what problems it’s going to bring.”

(COCODE leader, Focus group 2014)

The conversation, workshops and focus groups for the human rights risk assessment revealed that for many dam-threatened Q’eqchi’, the Xalalá project is perceived not as economic development, but rather as a new mechanism to dispossess them of their ancestral lands, part of a continuous history of dispossession and displacement that they have suffered since colonization. The Q’eqchi’ have been systematically deprived of their territorial rights in order to satisfy the economic interests of national and foreign landowners, the military, agro-industrial companies and drug traffickers [

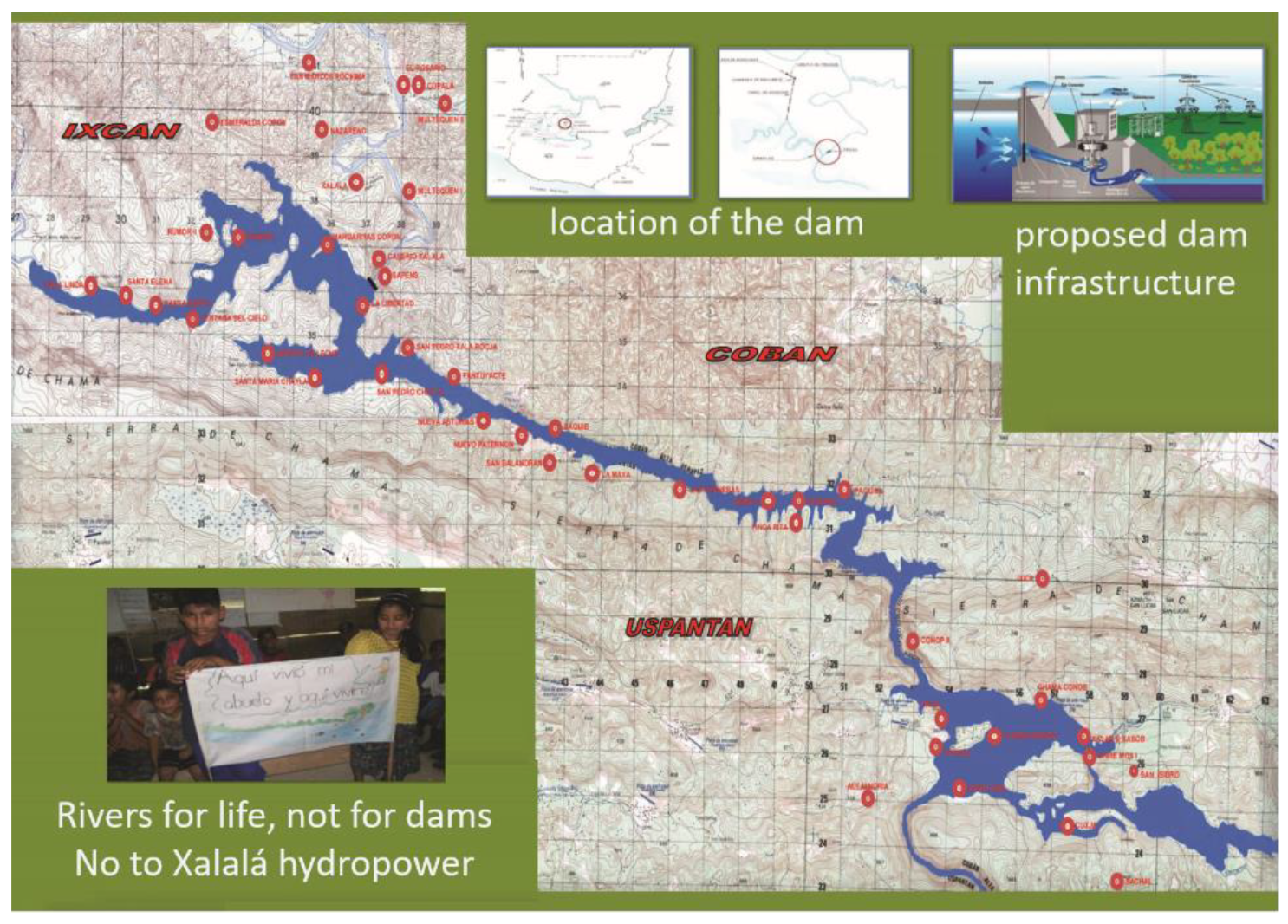

36]. Many participants were survivors of the massacres of the counter-insurgency, witnessed first-hand the scorched-earth policies against their communities and endured the imposition of the civil self-defense patrol system. It is estimated that in the region of Cobán, included in the area of influence of the Xalalá dam, they suffered at least 23 massacres and 36 of their communities were destroyed (this number is retrieved from the information gathered by Alfonso Huet during his collaborative study with genocide survivors in the region and matching it with INDE’s map of Xalalá’s impact zone. See [

37] and

Figure 1). As a consequence, the vast majority of the Q’eqchi’ living in the zone of influence are internally displaced persons or returnees who lived for many years as refugees in Mexico. Moreover, according to INDE 80 percent of the people living in the impact zone do not possess secure land tenure titles.

Many Maya Q’eqchi’ denote themselves as aj r’al ch’och, which literally means “sons and daughters of the land”, which expresses a deeply reciprocal multi-layered relationship with the land they live on. Together with loqlaj, which is commonly translated as “sacred”, and junajil, which means “oneness”, this refers to the interdependency between humans and the diverse visible and non-visible natural elements, in which well-being is not centralized to human beings nor does it start from the human but is indivisible between human beings and these “more-than-human” elements. It did not therefore come as a surprise that during the meetings many people referred to the Xalalá dam as another nimla rahila or deep suffering and pain. In the words of a Q’eqchi’ elder: “this project is another nimla rahilal for us, because just like in the 1980s, we human beings, the sacred hills and valleys and Mother Earth are going to suffer a lot”. During my PhD fieldwork in the mid-2000s, I learned that Maya Q’eqchi’ refer to what has been conceptualized by Western social and legal scholars as “internal armed conflict”, “genocide” and “gross human rights violations” as nimla rahilal, which means severe suffering and pain, localized not only at the individual physical and emotional level, but also at the collective level of the communities and the relational level with what is perceived to be “sacred” or “having dignity” (loq laj).

In Q’eqchi’ language, there is no literal translation for the legal concept of violation of a (human) right. During collaborative ethno-linguistic research focused on concepts, expressions and views concerning the war, post-conflict processes and transitional justice mechanisms, I learned that the Q’eqchi’ verb

muxuk refers to the desecration, transgression or violation of what is sacred and has dignity. Thus, this verb is used to refer not only to the sexual violation of humans, but also to the desecration or violation of non-human kinfolk such as the

Tzuultaq’a, maize, a river, a spring, a rock, a tortilla or a house by displaying unacceptable behavior. The bombings of the

Tzuultaq’a, the dead bodies in the Chixoy river, the burning down of the maize fields are, from a Q’eqchi’ ontological point of view, not just environmental damage but violations of the life of these sacred more-than-humans. As an elderly woman explained in 2007: “

Muxuk has been done in various ways; they [the army] dishonoured all the sacred hills [

Tzuultaq’a]. Because they threw big bombs, big grenades on the sacred hills, the sacred valleys, true, there we saved ourselves in the sacred hills, the mountains have a deity, true and we defended ourselves over there. Everybody defiled our dignity.” Elsewhere, I have argued that for many Q’eqchi survivors, victims and ex-Civil Defence Patroller (PAC) members, the violence they suffered during the armed conflict goes beyond the individual, collective and human field and also involves what are now increasingly called the more-than-humans, such as mountains, rivers, maize and animals [

38,

39].

Members of the Q’eqchi’ community therefore see the construction of the hydroelectric dam, which would imply the construction of a large water reservoir, as another

nimla rahilal, not only because of the massive displacement this will provoke, but also the destruction of the fertile lands, the many sacred caves and hills, the sacred maize fields, the killing of the family unit of the river Chixoy and the pollution of farmlands and the community’s water sources, provoking hunger. In this region, there are many caves that the spiritual guides use for performing

mayejak or sacrificial fire ceremonies to make their petitions to the

Tzuultaq’a. Moreover,

loqlaj ixim, or maize, is not only a substantial food supply for the Q’eqchi’ but is sacred and alive. As described elsewhere, the destruction of the maize fields during the conflict by the army and civil patrollers is not only perceived by the survivors as a violation of the human right to food, but as a desecration of the sacred plant. Around the planting and harvesting of maize, numerous rituals are performed to treat this plant with respect and dignity, because it is alive and also has its energy or spirit. In fact, the energy of the maize is even stronger than the spirits of other crops, which is why the Q’eqchi’ sometimes call it “

xtioxil li ixim” or “God” of maize (When Q’eqchi’ refer to “God”, this needs to be understood on the basis that the idea of a personal, transcendent God is not inherent in their cosmovision or ontology; however, many do not ignore the Christian God, as the majority of Q’eqchi’ are Catholic) [

40,

41,

42]. For this reason, under no circumstances should one step over the maize or throw seeds on the ground, nor should one put the basket of tortillas on the ground without a leaf or sack underneath. An important ritual that takes place the night before planting is what the Q’eqchi’ call the “watching of the seeds” or

yolek. The goal is that the maize seeds “have happiness in their hearts”, because if this is achieved, they will all germinate and produce healthy maize plants. During this ritual, the seeds “are being born” (

yalaak) and therefore need light, because “the seed cannot be born in the dark”. Since maize has an energy, there is a risk that when the seed is neglected, it may “get scared”, lose its spirit and not germinate. As many survivors explained during my Ph.D. research, “the maize is crying” when it was burned down during the scorched earth campaigns, and this would happen again when the Xalalá dam is constructed. The construction of the dam and the reservoir will not only destroy large areas of fertile fields and maize crops, but also block the watering systems from the river to the maize crops. As will be discussed in the next section, this will have a negative impact on the reciprocal and interdependent relationship of maize with the Q’eqchi’ as human beings.

During focus group meetings with elderly widows of the armed conflict that I organized in 2007, many said, referring to the violence, “we no longer want to suffer, we want tranquillity (tuqtuukilal)”. In one of the meetings for the policy report in 2014, one of the indigenous authorities put it this way: “We don’t agree with the Xalalá project because the government is already doing too much. In the 1980s we suffered the conflict, we can’t take it anymore, we’re tired of it.” This deep desire to feel and live in peace in their hearts, in their community, in their intimate relationship with the land, the caves and the water, is undermined and threatened once again by this megaproject in their territory. The Q’eqchi’ were very concerned about the future, thinking not only about the short-term negative impacts but also about the future of their children and grandchildren. “Where will our children live? Where will they cultivate their maize field?”, they ask aloud.

3.2. “Loqlaj Ha Yoyo’”, Water Is Life and Is Alive

“The hills began to emerge from the water and at once they became great mountains.”

(Popol Vuh)

While “water is a unique resource” and “without water there is no life” have become mainstream opening mantras of academic and policy publications discussing the numerous water controversies in different parts of the world, as well as the global water crisis that is threatening our planet, according to Maya Q’eqchi’ ontologies it is also alive. As a Q’eqchi’ elder explained, “water is the blood that flows in both women and men. Without water, the sacred hills and valleys cannot live and neither can human beings or animals.” As pointed out above, in Q’eqchi’ ontology, water is not perceived as an indep endent natural element but has an ongoing and interdependent relationship with the human beings and the more-than-humans, such as the land, the maize crops, the different water bodies and the animals. The Popol Vuh, regarded as a foundational written narrative of Maya oral history, which survived the book-burning campaigns of the Spanish conquistadores, explains that before the Earth there was a primordial silence in which there was only the sky and the calm sea. The Earth came into being when “the hills began to rise from the water and immediately became huge mountains”. In other words, water gives life to the earth, human beings and all the other inhabitants of this planet. Given this, it is not surprising that the dam-threatened Q’eqchi’ claim that “without electricity you can live, but not without water”. Or as an elderly woman put it, “water belongs to everyone and is vital, many people are going to suffer”.

The community members expressed their fear that the Xalalá dam would negatively affect the water sources that feed the streams in the region of the Chixoy river, which are vital for their agriculture and woods. According to the participants, its destruction would provoke struggles and conflicts among the community members over the scarcity of this vital element. The women also indicated that the lack of access to water would bring great poverty; as one Q’eqchi’ woman explained, “it brings poverty if we cannot use the water”. In addition, people stressed that water is fundamental for the survival of animals, both wild animals living in the mountains and domestic animals, which were going to die. As one Q’eqchi’ woman said, “the animals too, where are they going to get water to live?” Furthermore, they feared that contamination or total destruction would have negative impacts on their agricultural systems and the forest. The disappearance of the water sources would also impact on their spiritual practices because it would prevent them from performing the necessary rituals of giving food, wa’tesinq, to the water sources to ask for permission to use them.

During my follow-up stay at Nimlaha’kok in 2017, the region was facing a drought. This implied that there was no water running through the pipes in the wooden houses and the only water source for the whole community, almost 50 families, was a small stream ten minutes’ walk from the center of the community. In order to ensure that all families would have access to the stream, the community authorities had elaborated a time schedule for its access and use. In the early morning before 6 am, the men could go to fill the water jars in order to supply their households with water during the day. Between 6 am and 3 pm, women and children could go to the stream for personal bathing and washing clothes. After that time slot, men could go for a personal bath in the evening. This drought had a major impact on the organization of the families, and not having water for such an extended time became the main subject of our workshops and discussions.

During the different collaborative workshops (

Figure 5), the significance of water for the Maya Q’eqchi’ was further discussed: Water is alive. Women have a special relationship with water; as a Q’eqchi’ woman explained during a focus group, “without water we [women] cannot work. From the moment we get up, make coffee, wash, prepare food... everything is water.” The women emphasized that “men hardly work with water, they just get up and wash themselves. Or they wash their hands in a puddle when they come back from the milpa [maize field].” Conversely, women were in daily contact with water and felt its absence more acutely: “water is a life partner, like a husband, it is my partner every day. Without it we cannot live, it is part of our life.” For this reason, the Q’eqchi’ women said that their voice and opinion would be of utmost importance when the construction of the Xalalá hydroelectric dam was to be discussed.

One of the women elders shared her concerns:

When I grew up there was a lot of water, the little springs never dried up. There were so many fish, that’s where we fed ourselves. …they are already blocking the rivers, they are pouring poison into the rivers. We don’t respect each other, but we are all the same, children of one God. They’re saying that one day the water will run out, that it will only be possible to buy it by the barrel. I’m a widow, how am I going to do that? I can’t afford it.

Elders also shared that in the past they were more in contact or communication with water: “we used to greet the water every day when we went to the mountain to collect it... we were in communication with the water, with the stars.” They used to undertake the mayej, the ceremony to ask for permission. As one woman elder put it, “we were paying (tojok) with pom (incense) and candle to the water, to have permission to use it”. The reverence and care for water, a being, as they said, who never sleeps, was evident. One woman elder said:

My grandmother carried a candle and pom to ask the water’s permission, so that people and water would not feel shocked when they met. The grandmothers said you must greet the water. Cho na, so that it doesn’t get scared. There were words you had to use to greet the water before you started your day.

The perception of water and rivers as living beings was clear: Water gives life but is also alive. As one of the other women elders said, “the river has a heart, it lives, it has veins. My grandparents used to say, the veins are like the streams that come out of the big rivers. Water is the sweat of the earth. It does have a heart. If it didn’t, it wouldn’t be alive.”

3.3. Violations of Multiple Life Systems: Human Beings, Water Bodies, Mountains, Maize, Animals

“Rivers are the veins of the earth. A dam will cut the veins, so the river, the earth and us, we all die.”

(Maya Q’eqchi’ elder 2017)

A human rights assessment through the dominant Euro-Western lens would limit the rights at risk to, amongst others, the human right to water—access to water sources destroyed—and the human right to food—crops destroyed. However, the ethnographic landscape—multi-layered with sometimes contested and even contradictory meanings—described above shows that these legal conceptualizations stand in strong contrast to complex Maya Q’eqchi’ legal norms and practices rooted in their ontology as for them this impact goes far beyond the human: the lives of the “more-than-humans” are at stake. During my collaborative work on the genocide and transitional justice, I learned through the understanding of nimla rahilal that the Maya Q’eqchi’ survivors assign to the conflict that its impact goes beyond merely human rights violations of individuals and human beings. The Q’eqchi’ knowledge of the impact of the construction of the Xalalá dam points to the same ontological understandings. One of the elder spiritual guides explained in 2014 that the Chixoy river, which is the main river, the smaller side rivers, and the fertile river banks together, formed one family unit: A mother, a father and children. Thus, the Xalalá dam would destroy this nuclear family and violate the life of the Chixoy river: xmux’bal yuam nimla ha. As large rivers have, according to the Q’eqchi’, very strong energies, “the river will feel pain and suffer”. As described above, the hydroelectric project would deeply transgress and violate the sacred value and dignity of the river and the other interconnected elements such as the lands, side rivers and animals living in the rivers.

Elsewhere, I pointed out that as part of Maya Q’eqchi’ legal order, “an internal logic of the cosmos that, through an invisible spiritual force, fosters a new

tuqtuukilal or tranquillity” [

38] exists, which is known as

q’oqonk (stem is

q’oq). In the case of the sacred maize, when someone disrespects, desecrates or defiles maize, it causes a disharmony in the spiritual relationship with this sacred food. Thus, the maize suffers and feels pain, for which “the sacred maize is crying”. In fact, during the armed conflict the systematic cutting and burning of maize by the military and ex PAC not only caused famine among the displaced groups who sought refuge in the mountains, but also implied the destruction of the spiritual basis of the Q’eqchi’. According to the elders, the accumulation of sadness from the destruction of so much sacred maize for no reason provoked a strong reaction by their energies-spirits, which was expressed in poor harvests for many years after the armed conflict. As one old woman explained in a focus group in 2007, the sacred maize also made her

q’oq: “How much

q’oq of the sacred corn that was cut by the military. That’s why it is so hard what we are suffering now... That’s why the maizefield grows so little, it is very small.”

Within the context of the construction of the Xalalá dam, the elders were very clear that the river and the sacred mountains or Tzuultaq’a will react or take revenge for the damage done when humans do not treat them with respect and dignity they deserve. During the workshops for the policy report, the elders shared several narratives about people who drowned in the Chixoy River, for example former PAC chiefs who abused their power during the armed conflict. Moreover, several community members talked about recent landslides in a community in the Ixcán municipality on the other side of the river, which destroyed parts of that community. For non-Q’eqchi’ people, these landslides are perceived as natural disaster, but many Q’eqchi’ community members attributed them to a reaction of the Tzuultaq’a—the mountain has called—because of the population’s favorable attitude to the construction of the Xalalá hydroelectric plant and for having stopped practicing their Q’eqchi’ ceremonies as they converted to an evangelical church.

This negative reciprocity, or “Maya Q’eqchi’ scientific law”, is already unfolding according to Q’eqchi’ elders who participated in the workshops in 2017. One of the elders said, referring to the many hydroelectric dam projects in the region, “now they are cutting the veins of the earth because of the construction of the hydroelectric plants”, but “if they cut the river it will dry up. It’s as if the blood in your body dries up, it’s similar to what happens with water.” In fact, one of the elders explained the deep-rooted causes of the drought they were facing in the region as the “water is withdrawing because of deforestation. We’re killing the water ourselves. Our own pollution and negligence hurt the water, that’s why the water gets angry, that’s why the community stream dried up. Water sends us this sign that it is not happy, that it is sad.”

The elders recognized that it was partly a problem of education and intergenerational transmission of knowledge: “we are all guilty, we do not tell the children how to take care of the sacred water... these ideas are hard to speak about and to understand, young people do not believe us.” The women elders lamented along similar lines: “now water comes to the houses in pipes, we no longer greet the water” … “Young people do not know the sacred sites of the river so they do not ask for permission and they violate the life of the river (xmux’bal yuam nimla ha)”. The elders also recognized the negative effects of population growth and contemporary habits, saying that villagers cut down trees close to the springs and observing pollution “from plastics, soaps, pesticides, garbage”. The elders asked “why should children say good morning to the water if it comes from a pipe? When we were young we had to go to the hill to get water, it was a law to greet the water. Now young people don’t respect those ideas, they don’t want to listen... they make fun of us, everything has changed.”

However, respecting and taking care of these non-human kin is vital for keeping them alive. As one Q’eqchi’ elder explained, “when you go to a sacred place, you are not going to make a mess, to sully it. You have to go there asking permission, respecting it as if it were a person.”

4. Discussion: The Need for Critical Engagement with Plurilegal Water Ontologies

So far, ontological plurilegalities, such as the described Maya Q’eqchi’ plurilegal water ontologies, have been under-theorized in the fields of international human rights law and environmental law. Drawing on the above discussion of the multi-layered ethnographic landscape of Maya Q’eqchi’ human-water-life relationships in the context of a human rights risk assessment of hydropower development in territories severely affected by the armed conflict, in the discussion presented in the final section, I call for a new mindset in these international legal fields in order to pave the way for urgent rethinking of the human right to water and, more broadly, human rights by unsettling the modern divides of culture/nature and human/more-than-human. I therefore develop two broad theoretical and methodological perspectives and concerns, which should inform a comprehensive new research agenda, giving ecco to the French philosopher Descola, stating that “a good way to understand the status of a scientific problem is to study controversies” [

43].

First, I advocate recognition not only of the conceptual limitations of the dominant anthropocentric Euro-Western human rights paradigm in light of the climate emergency and global water crisis, but also of the ontological condition of law. Adopting a pluralistic legal lens is instructive for better grasping the underlying multi-layered, fluid and intergenerationally nuanced indigenous legal orders regarding human-water-life relationships. Second, I argue that once legal scholars embark on a theorization of these complex ontological legalities about the human–more-than-human, this should be critically empirically grounded and undo practices of ongoing colonial marginalization and recolonization of indigenous knowledges and practices.

While this urgent call for a fundamental rethink about ontology and human rights mainly stems from my long-term collaborative encounters with the Maya Q’eqchi, I am currently developing, with the financial support of a Starting Grant of the European Research Council (ERC) [

44], a five-year interdisciplinary research project called “RIVERS—Water/human rights beyond the human? Indigenous water ontologies, plurilegal encounters and interlegal translation” with the aim to strengthen the foundations of this presented call with innovative pluralist and comparative insights about indigenous legal human-water-life orders in the contexts of Nepal, Guatemala, Colombia and the UN human rights system.

4.1. Who Is Afraid of Plurilegal Water Ontologies?

Since my first ethnographic encounters with the Maya Q’eqchi’ some 20 years ago, my initial conceptual academic understandings about law and human-water-life relationships have evolved substantially over the different research projects. Through these multiple and not straightforward encounters in the context of old violence—armed conflict and genocide—and new violence—extractive development projects—I learned, amongst other things, that the dominant Euro-Western-centered legal tradition of human rights and international law broadly does not ontologically address multi-layered indigenous peoples’ legal conceptualizations, which are embedded in radically different visions and practices about respect for, harm to and violations of human–non-human relationships.

Regarding the old violence, therefore, as discussed elsewhere, dominant transitional justice mechanisms are falling short of responding efficiently to the needs and priorities of indigenous peoples regarding justice, reparation, memory, reconciliation and guarantees of non-repetition [

38,

45]. Regarding the new violence of extractive development projects in indigenous territories, the 2014–2015 human rights assessment policy research report discussed above was another critical turning point in my academic journey, because, even though the research already pointed clearly towards the central ontological political conflict about the Chixoy river and the Xalalá dam, namely a “conflict involving different assumptions about what exists” [

46], in my opinion, Guatemalan human rights defenders were not able to sufficiently recognize this “indigenous mode of being” [

47] regarding water and land and kept on leaning on the dominant Euro-Western legal human rights framework in their legal fight against this Xalalá dam project.

Reflecting on a report that was intended to honor the ontological visions and practices of the Maya Q’eqchi’ in their struggle and on the intrinsic limitations of this kind of human rights policy research report, it is imperative to recall the words of Māori scholar Tuhiwai Smith of three decades ago: the human rights field is also “a significant site of struggle between the interests and ways of knowing of the West and the interests and ways of resisting of the Other” [

48]. Indeed, when Maya Q’eqchi’ elderly women state that water and water bodies such as springs needs to be respected because they are alive, this should be taken seriously by human rights defenders and scholars and not just a strategic romantic belief that should mobilized to deal with the current environmental degradation. At the same time, it needs to be acknowledged that, as other legal anthropologists have pointed out, “law is a source of constituting and legitimating power” [

49], so it defines relations of power of people, institutions and organization over other people, institutions and organizations.

These premises about law, power and indigenous ontologies should be taken seriously by the increasing number of critical legal theoretical scholars who interrogate dominant Euro-Western legal positivistic assumptions about anthropocentrism, nature and environment in international human rights and environmental law. As mentioned in the introduction, there is a growing interest among environmental scholars in critically scrutinizing to what extent these dominant assumptions have contributed to the environmental degradation the world is facing and in calling for a rethink regarding how to use human rights and environmental law to mediate the human–environment/natural resources/nature relationship [

50,

51,

52,

53]. Rights of Nature (RoN), granting legal personhood to nature and its elements, such as rivers, is an emerging transnational legal framework fast gaining international traction among Euro-American legal scholars as a new tool for combatting environmental destruction.

In fact, according to the 11th Annual Report of the United Nations Program of Harmony with Nature there exists now a “mosaic of Earth-centred law for planetary health and human well-being”, as at least 35 countries have Rights of Nature legislation and policies in place [

54]. Its international proponents are promoting the idea that “ecosystems [including trees, oceans, animals and mountains] have the right to exist, thrive, and evolve” [

55], often claiming that RoN is rooted in indigenous lifestyles and views on nature/the environment.

However, so far neither critical legal theory scholars nor human rights and environmental legal scholars have engaged fully with ontological political conflicts about human-water-life, which water conflicts in indigenous territories demonstrate. The Q’eqchi’ were very clear that the Chixoy river, but also the maize and the sacred mountains, have agency, in a positive and negative reciprocal way. Or, as described elsewhere, “when humans harm non-humans or nature, an energy imbalance is created which implies changes in physical life. Global warming, water scarcity, disease and land infertility will appear” [

35]. To what extent, therefore, have the proponents of RoN considered the fact that by granting rights to rivers and other natural elements, whilst allegedly drawing on indigenous visions, these elements may also form an agency which might go against the interests of human beings? How will these RoN advocates deal with angry and sad rivers and other water bodies which cause droughts, bad harvests and deaths, as described above? So far, these RoN proponents, generally Euro-Western legal scholars, have generally not considered the possible negative impacts of essentializing and codifying indigenous visions and practices of nature [

56]. It seems that these critical legal scholars are afraid to engage deeply with the ontological questions and legal discomfort these water pluralities generate [

57,

58].

The contested, fluid and sometimes contradictory ethnographic accounts of the Xalalá water conflict demonstrate that the apparently simple concept of water assumes “complex unconscious meanings that need to be consciously sorted out” [

59]. A crucial task, therefore, is to address the many pressing questions and concerns that remain unanswered regarding multi-layered human-water-life relationships and meanings in contexts of human rights assessments of water conflicts in indigenous territories.

How do diverse indigenous peoples perceive and relate to water in daily practice in contexts of a continuation of colonial and racialized violence in their territories? What is ontologically at stake if indigenous peoples lose access to the continuous flow of rivers or to water sources due to these extractive projects? Regarding human rights assessments of risks arising from extractive development projects, an important question is whether the obstruction of the continuous flow of rivers by hydroelectric dams should be legally conceptualized as a violation of the human right to life, enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Political and Civil Rights, instead of the human right to water? Or should these rivers be granted legal personhood, as the international movement of RoN is promoting? How do water and water bodies, such as rivers, speak in the midst of sociopolitical conflicts provoked by extractive development projects? Another crucial question is to what extent will indigenous legal conceptualizations of the damage to rivers, mountains and other natural elements produced out of the analysis of dreams, fire ceremonies, consultations of sacred sites or bird songs be accepted as objective and scientific proof for legal practitioners during litigation in court or consultation (FPIC) processes?

Legal scholars who are embarking on this de-anthropocentric and ecocentric turn could draw useful lessons from the critical insights and ongoing debates about what has been coined as the ontological turn in social sciences. While this is a blind spot in international law and human rights scholarship, different fields in social sciences, such as Science and Technology Studies [

60,

61,

62,

63] and multispecies ethnography [

10,

64,

65], have already embarked on unsettling dominant modernist ontological assumptions and conceptualizations of culture/nature and human/more-than-human relationships and theorizing about the agency of non-humans, more-than-humans, other-than-humans. It is therefore imperative to create spaces for open and critical dialogue between mainstream human rights theory and these emerging theories and social science contributions.

At the same time, I propose that the adoption of a pluralistic legal lens would enable a critical analysis of the above-mentioned broad questions and multiple contestations over hegemonic, counter-hegemonic and ontologically legal understandings and indigenous practices of human-water-life relationships in different legal arenas. The conceptual framework of legal pluralism [

66,

67]—the existence of a plurality of legal orders stemming from different sources of legitimation within one sociopolitical space—is “an important element of the contexts in which human rights operate” [

68].

In daily life, this plurality of legal norms is shaped by interconnectedness or interlegality [

69,

70] and legal pluralism provides “a useful way of conceptualizing the interaction of all these various norm assertions and their potential efficacy” [

71]. At the same time, it should also be acknowledged, following the Canadian indigenous scholar Val Napoleon, that there is a need for deeper and more critical understanding of the strengths and principles of indigenous legal orders and how these can be used to deal with these multi-layered human-water-life rights issues [

72].

4.2. A Call for Bottom-Up Co-Theorizing about Human/Water beyond the Human

“We don’t have education, but we do have our ideas, thoughts and knowledge. This rules here.”

(Q’eqchi’ authority, workshop, 2014)

A crucial methodological concern arose through my different collaborative academic and policy research projects with the Maya Q’eqchi’: How to conduct empirical research into different conceptions of human-water-life that do not lead to the recolonization/appropriation of indigenous knowledge by non-indigenous scholarship and public policy. Currently, a welcome “empirical turn in international legal scholarship” [

73] is unfolding, which goes beyond the classical doctrinal method, a turn that is visible in the growing number of handbooks [

74,

75] about research methods and human rights, and in interdisciplinary methodological courses in legal training at universities, some important insights and lessons are needed to undo the role of legal scholarship in the ongoing oppression and marginalization of indigenous knowledge and practices. In the 1990s, Māori scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith critiqued the “positional superiority of Western knowledge” [

50] in academic knowledge production and the growing indigenous scholar community has been pointing out this continuing lack of recognition of indigenous knowledge as scientific knowledge [

76]. For example, regarding the above-mentioned popular but contested ontological turn, Canadian Métis scholar Zoe Todd writes about the “ongoing structural colonialism within the academia” [

76] (p. 4) because this Euro-Western academic ontological narrative spins on the back of non-European thinkers and practitioners without giving real credit to indigenous peoples.

In the discipline of law, indigenous legal scholars have also indicated that, despite the progressive advances in recognizing the collective human rights of indigenous peoples, in practice Eurocentric thinking, liberal individualism and Western legal culture continue to dominate their interpretation and application, making it difficult to realize their substantive self-determination [

77]. For example, indigenous knowledge is still marginalized to “uses and customs”, “customary law” and “infra-legal phenomena” in the mainstream legal and human rights field [

77]. Throughout my ethnographic encounters, many elders shared the above-mentioned concern, that because they do not master Spanish and never went to school, their knowledge and wisdom about the armed conflict and the dam’s impact is ignored and neglected by non-indigenous governmental officials, but also often by NGO collaborators and their own youth. Intimately connected is the fact that legal scholarship, and academia more broadly, have not sufficiently addressed “institutional racism” [

78] or its racial colonial legacies inscribed in legal theories and philosophies that have given birth to the human rights field [

79]. For example, regarding human rights risks assessments, one of the mayor concerns of indigenous elders, as explained above, is about taken seriously their indigenous knowledge and ontologies about harm and violations as legal evidence in impact assessments and court rooms.

Regarding research projects related to indigenous peoples, the former United Nations Special Rapporteur of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Vicky Tauli-Corpuz, observed:

Many academics, they come to collect the data and they use it to promote their career and in the end it is not helping the [indigenous] people that have been the ‘objects’ or ‘subjects’ of their research. It does not fit the framework that they have, … I think that is really sad and that is one part of the problems that indigenous peoples face, when the academia become the ‘experts’, and they always refer to them as the experts. When in fact, they gather all those things from indigenous peoples. So, I think the call is for the academia to acknowledge that the indigenous peoples from whom they collected this information are the experts [

80].

She recommends the participatory action research (PAR) framework [

48,

81,

82] that has been developed because:

This is really the framework that you need to work together with the people who are at the core of your subject, and then you really need to ensure that their views come into the whole framework. This is the basic thing, that the research is going to be done with the goal in mind of further enhancing the capacities of these peoples to be self-determining, to be able to have the capacity to assert that they should have their rights to their territories. [

80]

Indeed, when legal scholars are engaging with empirical work with indigenous peoples, they should take seriously Canadian Métís anthropologist Zoe Todd, who advises avoiding further ongoing appropriation of indigenous knowledge in Euro-Western research, including the use of indigenous ontologies without acknowledgment of indigenous thinkers, and the invisibility of indigenous scholars from European research settings [

76]. So indeed, it needs to be recognized that law is “not just rules, but a complex set of intellectual, social, political, and ethical practices” [

83]. Against these broader metrological concerns about the necessary process of decolonizing research methods, I urge that legal theorical research, when embarking on an empirical turn about human rights, such as the human right to water, RoN and environmental law, should also support indigenous peoples to reclaim control over their own ways of knowing, being and living.