Learning from Floods—How a Community Develops Future Resilience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background Literature

2.1. The Concept of Flood Risk

2.2. Response and Recover from Floods

2.3. Community Response Plan (CRP)

3. Research Methods

3.1. Interview and Surveys

3.2. Catchment Group Meeting and Field Observations

3.3. Desktop Analysis

4. Result and Discussion

4.1. Flood Response and Recovery at the Community Level

4.1.1. Volunteer

- Volunteers who have connected with CDEMG training, provided or facilitated by CDEMG

- Affiliated volunteer organisations such as Northland Red Cross

- Spontaneous volunteers who are members of the general public or community groups who respond spontaneously to emergencies

4.1.2. Working Together after Flood

4.2. Involvement of Communities in Flood Protection Strategies

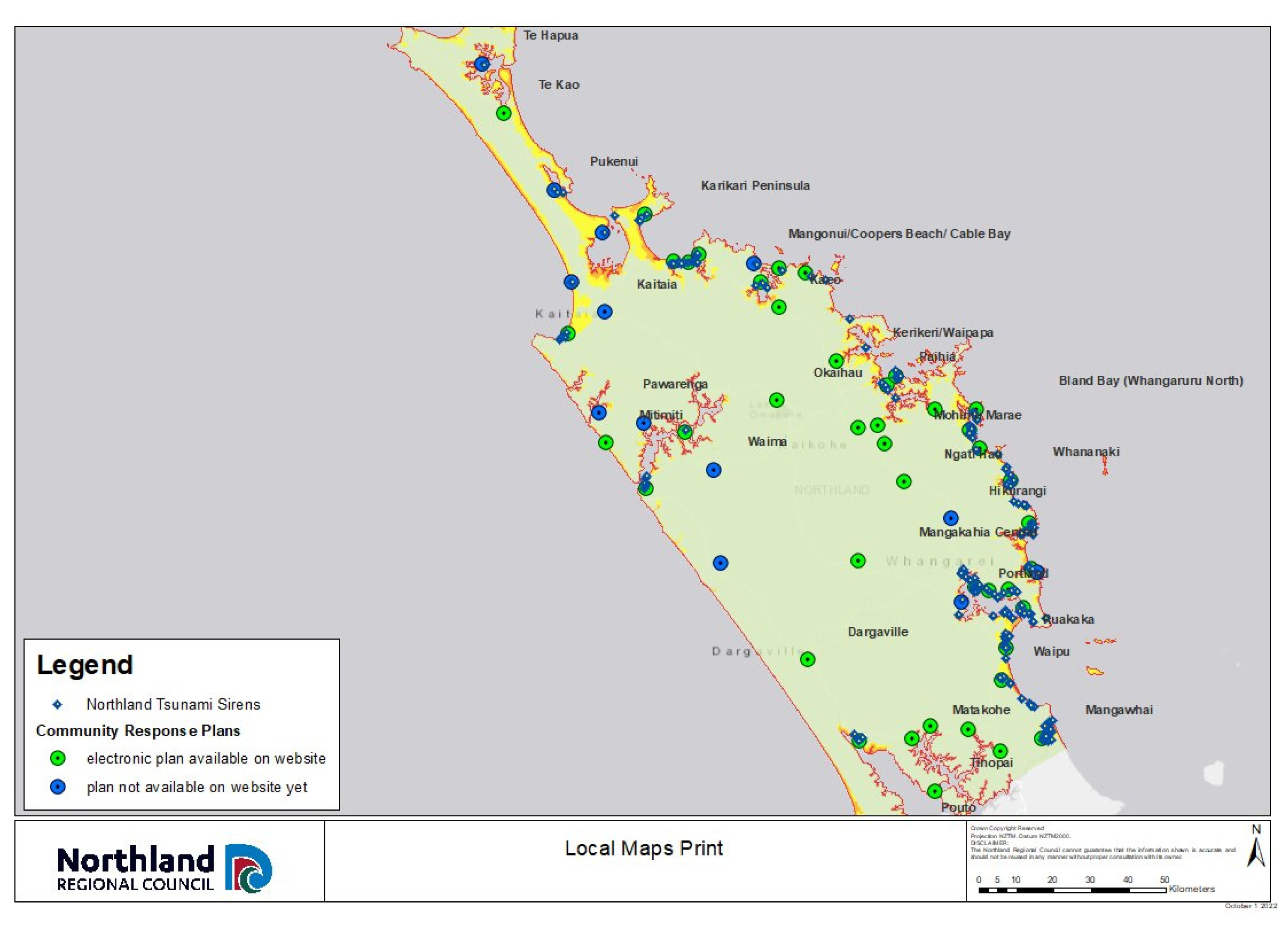

4.3. Community Engagement in the Northland

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Objectives | Actions | Lead Agency |

|---|---|---|

| Increase the level of business and community awareness through public education and consultation |

| CDEMG |

| Improve community participation and preparedness through community-based planning |

| CDEMG, in partnership with Community Groups |

| Provide effective warning systems to enable agencies and the communities to respond rapidly to potential events |

| CDEMG |

| Main Project | Identified Issues | Offered Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Taumarere Flood Management Working Group Friday, 6 August 2021 | ||

|

|

|

| Kaihū River Working Group Friday, 13 August 2021 | ||

|

|

|

| Kāeo River-Whangaroa Catchment Group Friday, 30 July 2021 | ||

|

|

|

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Adams, H., Adler, C., Aldunce, P., Ali, E., Begum, R.A., Betts, R., Kerr, R.B., Biesbroek, R., et al., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- The Royal Society of New Zealand. Climate Change Implications for New Zealand. Available online: https://www.royalsociety.org.nz/assets/documents/Climate-change-implications-for-NZ-2016-report-web3.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Ogie, R.I.; Adam, C.; Perez, P. A review of structural approach to flood management in coastal megacities of developing nations: Current research and future directions. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auliagisni, W.; Wilkinson, S.; Elkharboutly, M. Using community-based flood maps to explain flood hazards in Northland, New Zealand. Prog. Disaster Sci. 2022, 14, 100229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry for the Environment. Meeting the Challenges of Future Flooding in New Zealand; Ministry for the Environment: Wellington, New Zealand, 2008.

- Rouse, H. Flood Risk Managemnet Research in New Zealand: Where We Are and Where Are We Going? National Institute of Water & Atmospheric Research Ltd.: Wellington, New Zealand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Northland Regional Council. River Flooding; Natural Hazard Portal. 2022. Available online: https://www.nrc.govt.nz/environment/natural-hazards-portal/river-flooding/ (accessed on 6 October 2022).

- Northland Regional Council. July 2020 Climate Report; Northland Regional Council: Whangarei, New Zealand, 2020.

- Dinsdale, M. Northland Storm: Hundreds Still without Power and Kaitaia Remains Cut Off Due to Flooding, Slips in Nzherald 2022. Available online: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/ (accessed on 6 October 2022).

- Clent, D. Surface Flooding, Rapid River Rise, as ‘Significant’ Rainfall Hits Northland in Stuff. 2021. Available online: https://www.stuff.co.nz/ (accessed on 4 October 2022).

- McSaveney, E. Floods; Te Ara—The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. 2006. Available online: http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/floods (accessed on 30 September 2022).

- Zevenbergen, C.; Gersonius, B.; Radhakrishan, M. Flood Resilience; The Royal Society Publishing: London, UK, 2020; p. 20190212. [Google Scholar]

- McClymont, K.; Morrison, D.; Beevers, L.; Carmen, E. Flood resilience: A systematic review. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 1151–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munawar, H.S.; Khan, S.I.; Anum, N.; Qadir, Z.; Kouzani, A.Z.; Parvez Mahmud, M.A. Post-Flood Risk Management and Resilience Building Practices: A Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersonius, B.; van Buuren, A.; Zethof, M.; Kelder, E. Resilient flood risk strategies: Institutional preconditions for implementation. Ecol. Soc. 2016, 21, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NRC. The Northland Regional Council’s Long Term Plan 2021–2031; Northland Regional Council: Whangarei, New Zealand, 2021.

- Blakeley, R.W.G. Building Community Resilience; New Zealand Society of Local Government Managers: Wellington, New Zealand, 2016.

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; UN Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2015.

- Binns, A.D. Sustainable development and flood risk management. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2022, 15, e12807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarigakis, A.K.; Jimenez-Cisneros, B.E. UNESCO’s contribution to face global water challenges. Water 2019, 11, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechowska, E. What determines flood risk perception? A review of factors of flood risk perception and relations between its basic elements. Nat. Hazards 2018, 94, 1341–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, D.; Liao, K.-H. Learning from Floods: Linking flood experience and flood resilience. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 271, 111025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schanze, J. Flood risk management—A basic framework. In Flood Risk Management: Hazards, Vulnerability and Mitigation Measures; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, G. Learning to live with rivers—The ICE’s report to government. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.-Civ. Eng. 2002, 150, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIWA. Flooding—how Does It Happen? 2016. Available online: https://niwa.co.nz/natural-hazards/extreme-weather-heavy-rainfall/flooding-how-does-it-happen (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- Reese, S.; Becker, J.S.; Johnston, D.M.; Coomer, M.A.; Tuohy, R. Flood perceptions, preparedness and response to warnings in Kaitaia, Northland, New Zealand: Results from surveys in 2006 and 2009. GNS Science Report 2011/10; GNS Science: Lower Hutt, New Zealand, 2011; 90p. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.J.; Brown, S.; Dugar, S. Community-based early warning systems for flood risk mitigation in Nepal. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2017, 17, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WMO. The Role of Land-Use Planning in Flood Management; Integrated Flood Management Tools Series; World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Narayan, S.; Hanson, S.; Nicholls, R.; Clarke, D. Use of the Source–Pathway–Receptor–Consequence Model in Coastal Flood Risk Assessment. Geophys. Res. Abstr. 2011, 13, EGU2011-10394. [Google Scholar]

- Hutter, G. Strategies for Flood Risk Management—A Process Perspective; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; pp. 229–246. [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Advanced Engineering. Managing Flood Risk: Draft New Zealand Protocol. Centre for Advanced Engineering, Ed.; Centre for Advanced Engineering, University of Canterbury Campus: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rollason, E.; Bracken, L.J.; Hardy, R.J.; Large, A.R.G. Rethinking flood risk communication. Nat. Hazards 2018, 92, 1665–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maidl, E.; Buchecker, M. Raising risk preparedness by flood risk communication. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2015, 15, 1577–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proverbs, D.G.; Soetanto, R. Flood Damaged Property: A Guide to Repair; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Boobier, T. The Development of Standards in Flood Damage Repairs. In Flood Hazards: Impacts and Responses for the Built Environment; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; p. 125. [Google Scholar]

- Abhijeet, D.; Eun Ho, O.; Makarand, H. Impact of flood damaged critical infrastructure on communities and industries. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2011, 1, 156–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapsell, S.M.; Penning-Rowsell, E.C.; Tunstall, S.M.; Wilson, T.L. Vulnerability to flooding: Health and social dimensions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. Ser. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2002, 360, 1511–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, G. Managing natural hazard risk in New Zealand—Towards more resilient Communities; LGNZ and Regional Councils: Wellington, New Zealand, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hermans, O.F. Flood Management in New Zealand: Exploring Management and Practice in Otago and the Manawatu. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- MCDEM. National Disaster Resilience Strategy; Ministry of Civil Defence & Emergency Management: Wellington, New Zealand, 2019.

- Samaddar, S.; Misra, B.; Tatano, H. Flood risk awareness and preparedness: The role of trust in information sources. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Seoul, Korea, 14–17 October 2012; pp. 3099–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NEMA. The 4 Rs. Available online: https://www.civildefence.govt.nz/cdem-sector/the-4rs/ (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Northland-CDEM. Northland Civil Defence Emergency Management Group Plan 2021–2026; Northland—Setting the Scene; Northland Civil Defence Emergency Management Group: Whangarei, New Zealand, 2021.

- The Ministry of Civil Defence & Emergency Management. Community Engagement in the CDEM context. In Best Practice Guideline for Civil Defence Emergency Management Sector [BPG 4/10]; Director of Civil Defence Emergency Management: Wellington, New Zealand, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, N.; Elliott, M.; Simonovic, S.P. Risk and Resilience: A Case of Perception versus Reality in Flood Management. Water 2020, 12, 1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northland Regional Council. Community Response Plan. 2022. Available online: https://www.nrc.govt.nz/civildefence/Community-Response-Plans/ (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Grothmann, T.; Reusswig, F. People at risk of flooding: Why some residents take precautionary action while others do not. Nat. Hazards 2006, 38, 101–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, K.; Lindberg, K.; Haenfling, C.; Schori, A.; Marsters, H.; Read, D.; Borman, B. Social Vulnerability Indicators for Flooding in Aotearoa New Zealand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempen, A. Community safety tips-are you and your family prepared for disasters and extreme weather conditions? Servamus Community-Based Saf. Secur. Mag. 2017, 110, 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, J.A.; Wadsworth, M. Out of the floodwaters, but not yet on dry ground: Experiences of displacement and adjustment in adolescents and their parents following Hurricane Katrina. Child. Youth Environ. 2008, 18, 354–370. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, H.F. Effective leadership response to crisis. Strategy Leadersh. 2006, 34, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, R. Post disaster recovery: Issues and challenges. In Disaster Recovery; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chinh, D.T.; Bubeck, P.; Dung, N.V.; Kreibich, H. The 2011 flood event in the Mekong Delta: Preparedness, response, damage and recovery of private households and small businesses. Disasters 2016, 40, 753–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handmer, J. Are flood warnings futile? Risk communication in emergencies. Australas. J. Disaster Trauma 2000. Available online: http://www.massey.ac.nz/~trauma/issues/2000-2/handmer.htm (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Yodsuban, P.; Nuntaboot, K. Community-based flood disaster management for older adults in southern of Thailand: A qualitative study. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2021, 8, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, D.N.T.; Goff, J.; Skipper, A. Māori environmental knowledge and natural hazards in Aotearoa-New Zealand. J. R. Soc. N.Z. 2007, 37, 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, E.-M. Toi Tu Te Whenua, Toi Tu Te Tangata: A Holistic Māori Approach to Flood Management in Pawarenga. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan, A.D.; Waitoki, W. Collective action by Māori in response to flooding in the southern Rangitīkei region. Int. J. Health Promot. Educ. 2022, 60, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northland Regional Council. Northland Regional Council Website Resources. Available online: www.nrc.govt.nz (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Northland Regional Council. Web Page: River Flood Management Programme. 2022. Available online: https://www.nrc.govt.nz/environment/natural-hazards-portal/flood-risk-management/river-flood-management-programme/ (accessed on 2 January 2022).

- Kumar, R. Research Methodology: A Step-By-Step Guide for Beginners, 5th ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- BRANZ. Restoring a home after flood damage. In BRANZ Bulletin; BRANZ: Judgeford, New Zealand, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Northland Regional Council. Infrastructure Strategy: Flood Protection and Control—Rautaki Hanganga; Northland Regional Council: Whangarei, New Zealand, 2018.

- NRC. Whangarei Flood Detention Dam Investment Pays Off; NRC Media Releases; Northland Regional Council: Whangarei, New Zealand, 2020.

- NRC. Awanui Flood Scheme Proves Worth; NRC Media Releases; Northland Regional Council: Whangarei, New Zealand, 2022.

- Jakku, E.; Lynam, T. What Is Adaptive Capacity. In South East Queensland Climate Adaptation Research Initiative; Climate Adaptation National Research Flagship; CSIRO: Canberra, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- NRC. Tangata Whenua. 2012. Available online: https://www.nrc.govt.nz/resource-library-archive/environmental-monitoring-archive2/state-of-the-environment-report-archive/2011/state-of-the-environment-monitoring/our-people/tangata-whenua/ (accessed on 5 January 2022).

- Kowhai, T.R. Māori Cultural Sites Will Be among the Most Vulnerable to Climate Change and Rising Sea Levels; Newshub: Auckland, New Zealand, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Koopman, J. The restoration of gotong royong as a form of post-disaster solidarity in Lombok, Indonesia. South East Asia Res. 2021, 29, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souisa, H. Indigenous Peoples ‘Take Enough’ in Natural Wealth Management to Avoid Disaster. ABC News 26 November 2021. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/ (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Zhang, H.; Nakagawa, H. 5—Validation of indigenous knowledge for disaster resilience against river flooding and bank erosion. In Science and Technology in Disaster Risk Reduction in Asia; Shaw, R., Shiwaku, K., Izumi, T., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shava, S.; Krasny, M.; Tidball, K.; O’Donoghue, R. Local knowledges as a source of community resilience. Environ. Educ. Res. 2010, 16, 325–339. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, M.-U.-I.; Haque, C.E.; Nishat, A.; Byrne, S. Social learning for building community resilience to cyclones: Role of indigenous and local knowledge, power, and institutions in coastal Bangladesh. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Response Level | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| National | Includes agency coordination centres, national level sector coordinating entities, and government coordination across national agencies. Coordinated from National Coordination Centres (NCCs) | A large ex-cyclone storm or tsunami impact will require a response from all levels. |

| Regional | Includes Civil Defence and Emergency Management Group’s (CDEMG) stakeholders and partners. Coordinated from Emergency Coordination Centres (ECCs) or Emergency Operation Centres (EOCs) | Wide-scale flooding across the region will require a regional, local, incident, and community response. |

| Local | Includes district councils, stakeholders and partners at the local (district/city) level. Coordinated from ECCs or EOCs | A major flood in townships removes people from their homes for an extended time. Support may be required from a local, incident, and community level. |

| Incident | The first official level of agency response. It includes first responders. Coordinated from Incident Control Points (ICP) | A road closure or road traffic accident due to surface flooding will require an incident-level response. |

| Community | The general public, including individuals, families/whanau, community groups and businesses |

| Damages | Long Term Consequence | Clean-Up Action |

|---|---|---|

| Mud on the walls | Dried mud is harder to clean and can deteriorate the structure | Wash with clean water, soap, and vinegar solution, as bleach is more harmful to the environment. However, too much acid is not recommended as it can damage the walls. |

| Cavities | Dirty areas support the growth of disease-causing microorganisms carried in floodwater. | Clean with high-pressure water and use Liquid household cleaners to remove mud, silt, and greasy deposits. |

| Mud on the floors and carpet | Not adequately cleaned floor can damage the structure of the floors and cause mould growth and other disease-causing microorganisms. | Shovel the mud, remove the coverings, clean pressurised water, disinfects, and dry before reapplying the covering. A carpet cleaner company also can help to make sure the covering is safe and germ-free |

| Heating duct | Breathing chemicals or biological pollutants in conditioned air | Replace or hire professionals to clean |

| Wet lining board | Mouldy and crack when it dries | Clean with a damp cloth and disinfect before dry |

| Swollen doors | Growing mould or jammed | Clean with disinfectant and use a dehumidifier, heat gun, or hair dryer to dry the doors. If still jammed after it dries, sand the doors. |

| Electricity and gas | Fire hazard risk, and electricity failure or electrocuted | Use a torch when entering, do not use candles or any open fire. Switch off the electricity supply at the fuse box and gas supply if it is safe. If it is affected by water, seek professional advice. Unplug damaged electrical appliances and assess the condition before use. |

| Water | Health problem | Do not use until it is clean and even after it comes out clean, still treat the water before use. Boils the water or buy fresh water for safety. |

| Furniture | Damaged and mouldy furniture | Move to the clean and dry area, clean with a cloth, and disinfects before drying. |

| Paddocks | Cutting the access and affecting the plants or live stocks. Contaminated slits or slips can happen. | Clean access ways, be aware of hazards and check the water supply. Assess each paddock for damage and soil test slit before regressing. Some paddocks need immediate action, while others need to dry before action, depending on the situation. |

| Protection Plan | Program | Community Involvement |

|---|---|---|

| Flood protection infrastructure | Awanui | Involvement of community members in the planning, construction, decision-making and ongoing management |

| Kaeo-Whangaroa | ||

| Whangarei dam | ||

| Kerikeri-Waipapa | ||

| Taumarere | ||

| Drainage scheme | Raupo drainage scheme | Maintain property’s healthy drainage system around property and neighbourhood |

| Hikurangi swamp | ||

| Kaitaia swamp | ||

| River management | Erosion control | Landowners are responsible for the normal maintenance of rivers and streams on and around their property. |

| Clearing blockages | ||

| Gravel management | ||

| Vegetation management |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Auliagisni, W.; Wilkinson, S.; Elkharboutly, M. Learning from Floods—How a Community Develops Future Resilience. Water 2022, 14, 3238. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14203238

Auliagisni W, Wilkinson S, Elkharboutly M. Learning from Floods—How a Community Develops Future Resilience. Water. 2022; 14(20):3238. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14203238

Chicago/Turabian StyleAuliagisni, Widi, Suzanne Wilkinson, and Mohamed Elkharboutly. 2022. "Learning from Floods—How a Community Develops Future Resilience" Water 14, no. 20: 3238. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14203238

APA StyleAuliagisni, W., Wilkinson, S., & Elkharboutly, M. (2022). Learning from Floods—How a Community Develops Future Resilience. Water, 14(20), 3238. https://doi.org/10.3390/w14203238