Possibilities of Using the Unitization Model in the Development of Transboundary Groundwater Deposits

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- application of unified mechanisms of legal regulation of the transboundary deposits development;

- development of the field according to a single project for all parties and a single estimate.

- unit area—territory described in the unitization agreement on which exploration and exploitation under the unitization agreement (unit) is being conducted; license holders pooled under the unitization agreement;

- participating area—the part of the combined territory that, based on geological data, is considered to contain in profitable quantities the minerals for which the association was carried out, or the part that is necessary to carry out work on the combined territory and in whose favor the extracted minerals are deducted (unitization site);

- unitized substances—oil and gas lying in the bowels of the united territory and extracted in profitable quantities in accordance with the unitization agreement;

- unit operator—a legal entity or its subdivision that conducts the unit’s activities;

- unit owners—participants of the unitization agreement, represented by licensees;

- working interest—rights to part of the united fossil or rights to the land in which they are deposited.

- (1)

- the territory of the agreement, consisting of several plots;

- (2)

- the obligation of the parties to develop the field according to a single approved project and according to a single agreed estimate;

- (3)

- shares in the unitization agreement and the procedure for revaluation of equity participation;

- (4)

- the procedure for the assessment and revaluation of mineral reserves for the purposes of distribution of extracted products;

- (5)

- the procedure for the distribution and redistribution of extracted products and costs between subsoil users;

- (6)

- the establishment of a governing body charged with supervising operations under the agreement;

- (7)

- the designation of the legal entity conducting the activities of the association, determination of its rights and obligations;

- (8)

- procedure for drawing up and approving cost estimates and development programs;

- (9)

- information exchange procedure;

- (10)

- features of the customs regime;

- (11)

- taxation and accounting.

3. Results

- the deposit is being developed as a single operational facility (block) by the block operator on the basis of a jointly approved development plan;

- each state shall establish a legal framework for the binding conclusion of agreements both between licensees within the state and with licensees from other states;

- the states, each for its part, must necessarily agree on the territory and boundaries of the operational facility (with the possibility of subsequent border changes if necessary), determine the specifics of the procedures for calculating and reevaluating reserves, as well as determine the corresponding shares of reserves attributable to each of the parties to the agreement;

- each of the states agrees with the approved estimate of income and expenses commensurate with their share in the agreement, in connection with which they receive income and are calculated for their obligations in the process of developing an asset in accordance with approved standards, regardless of which state is producing hydrocarbons at the moment;

- each of the states determines the conditions of the tax policy and agrees not to take other measures of fiscal impact other than those provided for in the agreement, etc.

- determination of the principles of distribution of hydrocarbon reserves of the deposits between the participating states;

- coordination of the unified operation plan and its coordination by license holders;

- providing mechanisms for resolving disputes that may arise during the development of the field.

4. Discussion

Comparison of the Unitization Agreement with Similar Legal Acts

- (1)

- The parties to the agreements work together to achieve a common goal.

- (2)

- The parties to the agreements do not act in relation to each other in the role of debtor and creditor.

- (3)

- They do not form a new legal entity.

- (4)

- The agreements are based on the participants’ shared ownership of common property.

- (5)

- The parties to the agreements are responsible for the debts with their own property.

- (6)

- The common property of the participants is independently accounted for on a separate balance sheet.

- (7)

- The total profit of the participants is usually distributed in proportion to their share in the agreement.

- 1

- (a) A joint activity agreement is a civil contract based on the freedom of expression of the will of the parties;(b) A unitization agreement may be of an administrative, compulsory nature, since the participants may be required to conclude it by law.

- 2

- (a) A joint activity agreement may be either urgent or indefinite;(b) A unitization agreement is of an urgent nature.

- 3

- (a) Less than two participants (co-partners) may not participate in a joint activity agreement;(b) The establishment of a unit allows for the possibility of one participant’s activity.

- 4

- (a) As a general rule, the parties to the agreement on joint activities make decisions on common cases unanimously (by agreement of all participants in a simple partnership). A single management body is not created for a simple partnership;

- 5

- (b) The participants of the unitization agreement create a joint management committee.

- 6

- (a) The conduct of common affairs under a joint activity agreement may not be carried out by the partnership itself, nor by any of its bodies, only either jointly by all participants, or by any of the participants on the basis of a power of attorney;(b) The management of the unit’s affairs under the unitization agreement is transferred to the operator.

- 7

- (a) Members of a simple partnership are liable in solido;(b) The members of the unit bear shared responsibility for all common obligations.

- 8

- (a) The participants of a simple partnership do not revalue their initial participation shares;(b) The participants of the unit must re-evaluate the initial shares of their participation.

- 9

- (a) When transferring the rights of a participant leaving the partnership, the pre-emptive right to his share belongs to other participants of the partnership;(b) The transfer of rights under the unitization agreement can be carried out only with the consent of the state.

- 10

- (a) The agreement on joint activities is not subject to state registration (the exception is the creation of a financial and industrial group);

- 11

- (b) The unitization agreement must be approved by the appropriate governmental authority.

- -

- The U.C. is created on the basis of an interstate agreement;

- -

- The U.C. has access to the information base of the state monitoring system on the transboundary territory online;

- -

- The U.C. has corrective, complementary relations with the department of licensing of subsurface use (extraction of groundwater);

- -

- The U.C. correspond with the main organizations with production volumes over 500 m3/day, as well as mining enterprises producing water supply (drainage) in the zone of the transboundary territory;

- -

- The U.C. has an analytical numerical apparatus for the possibility of constructing an independent forecast;

- -

- The U.C. has the authority to make adjustments to the amount of water intake in certain areas within the framework of the general balance scheme of groundwater extraction management;

- -

- The U.C. has the right to assess the reliability of the initial basic information on the operating mode and measurements of the pressure state and hydrochemical composition;

- -

- The U.C. may consist of both transboundary states; one of the transboundary states or of independent experts from third countries.

- Coordination of the groundwater resources management system in neighboring state territories;

- Unified methodology and standardization of monitoring and exchange of geological information;

- Legal aspects of the activities of water intake enterprises and mining companies in the context of the development of groundwater space;

- The presence of a monitoring network for solving cross-border regulation, coordinated on both sides of the state border in the form of observation wells and other observation points.

- Hydrodynamic schematization of transboundary territories taking into account the results of geological exploration, namely: filtration parameters, boundary hydrogeological conditions, assessment of the natural flow modulus, hydrochemical zonality, conditions of interaction of aquifers;

- Establishment of limit parameters of extraction or change of hydrochemical parameters during the operation of aquifers;

- Establish a zone of responsibility on a transboundary territory, characterize the width (strip) along the border, the size of which can be determined by the radius of influence of Rimp (Equation (1)), independent of the performance of water intake, as well as internal zonality based on the calculation of the radius of formation of reserves for a single water intake

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The unitization company (hereinafter referred to as the U.C.), as a coordinating structure at the interstate level, should partially assume the management functions. State models and principles of water management in different countries have a number of differences, which means that delegating part of their functions to the U.C. will help to connect at the legislative and executive international level;

- (2)

- The field of activity of the U.C. should have restrictions based on the estimated areas of responsibility for the operation of groundwater, based on geological and hydrogeological calculations and assessment of the degree of development of underground water space;

- (3)

- The activity of the U.C. should be based on highly qualified specialists who have the necessary degree of trust from both contracting parties;

- (4)

- The U.C. is financed by both states parties to the unitization agreements with a mandatory planning and reporting model of interaction;

- (5)

- The U.C. builds the ideology of groundwater extraction management in both adjacent border territories, including the layout of the monitoring network based on hydrogeological schemes and parameters of the main aquifers and water barriers. The analysis of the hydrogeological situation during the operation of the main aquifers will make it possible to perform the main function of the U.C.—to adjust the productivity of all water intakes on a transboundary territory, as well as their intra-territorial location;

- (6)

- In most states where fresh and ultra-fresh groundwater is not a marketable product within the framework of the fields being developed, that is, it does not yet have a cost estimate, the formation of the U.C. budget is possible only from state earmarked funds. Nevertheless, a number of states in the Near and Middle East, Africa, and the Asian region experiencing an acute shortage of fresh water resources can and should transfer the financing of the U.C. to the principles of an investment mechanism or concession.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mironova, A.V.; Molsky, E.V.; Rumanin, V.G. Transboundary problems in the exploitation of groundwater in the region of the state border of Russia–Estonia (on the example of the Lomonosov—Voronkovsky aquifer). Water Resour. 2006, 33, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaminé, H.I.; Afonso, M.J.; Barbieri, M. Advances in Urban Groundwater and Sustainable Water Resources Management and Planning: Insights for Improved Designs with Nature, Hazards, and Society. Water 2022, 14, 3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilov-Danilyan, V.I.; Khranovich, I.L. Water resources management. In Harmonizing Water Use Strategies; SC World, 2010; 229p, Available online: http://www.cawater-info.net/review/pdf/russia_wm3.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Danilov-Danilyan, V.I.; Demin, A.P.; Pryazhinskaya, V.G.; Pokidysheva, I.V. Markets for water and water management services in the world and the Russian Federation. Part II. Water Resour. 2015, 42, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Development Goals, Goal №. 6. Clean Water and Sanitation. Available online: https://www.un-ilibrary.org/content/books/9789210474030/read (accessed on 31 August 2022).

- Convention on the Regime of Navigation on the DANUBE. 1948. Available online: https://www.danubecommission.org/uploads/doc/convention-ru.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- UNECE Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and International Lakes, Helsinki. 1992. Available online: https://treaties.un.org/doc/Treaties/1992/03/19920317%2005-46%20AM/Ch_XXVII_05p.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2022).

- UN General Assembly Resolution 63/124 on the Law of Transboundary Aquifers. Report of the International Law Commission Sixtieth Session 2008. Supplement No. 10 (A/63/10). Available online: https://www.un.org/ru/documents/decl_conv/conventions/pdf/intorg_responsibility.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- UNESCO 2013–2015 GRGTA (Groundwater Resources Governance in Transboundary Aquifers). Available online: unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002430/243003r.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Cherepovitsyn, A.; Moe, A.; Smirnova, N. Development of transboundary hydrocarbon fields: Legal and economic aspects. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2016, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mareeva, S.Y. Legal Regulation of the Use of Transboundary Mineral Deposits. Ph.D. Thesis, Moscow, Russia, State Institution “Center for the Preparation and Implementation of Production Sharing Agreements and Regulatory Support for Subsoil Use” (Center “SRP-Nedra”), Ministry of Natural Resources of the Russian Federation. 2004. Available online: http://www.dissercat.com/content/pravovoe-regulirovanie-ispolzovaniya-transgranichnykh-mestorozhdenii-poleznykh-iskopaemykh#ixzz4N2tDJmin (accessed on 31 July 2022).

- Cherepovitsyn, A.E.; Ilinova, A.A.; Romasheva, N.V. Key stakeholders in the development of transboundary hydrocarbon deposits: The interaction potential and the degree of influence. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 16, 1–12. Available online: https://www.abacademies.org/articles/key-stakeholders-in-the-development-of-transboundary-hydrocarbon-deposits-the-interaction-potential-and-the-degree-of-influence-6850.html (accessed on 10 August 2022).

- Ulyanov, V.S.; Dyachkova, E.A. Analysis of the World Experience in Regulating the Development of the Deposits Intersected by the State, Administrative Boundaries and the Boundaries of the Licensed Areas. 1998. Available online: http://www.yabloko.ru/Publ/Unit/unit.html (accessed on 7 August 2022).

- Lyons, Y. Trans-Boundary Pollution from Offshore Oil and Gas Activities in the Seas of Southeast Asia. In Trans-Boundary Environmental Governance: Inland, Coastal and Marine Perspectives; University of Wollongong; Ashgate Publishing Ltd.: Wollongong, Australia, 2012; pp. 167–202. [Google Scholar]

- Nikanorova, A.D.; Egorov, S.A. Formation of principles and norms regulating the use of transboundary water resources by states. Water Resour. 2019, 46, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubtsova, A.I. International Relations in the Eastern Mediterranean Region and the Problem of Transboundary Hydrocarbon Resources. Ph.D. Thesis, Russian State Pedagogical University, Saint Petersburg, Russia, 2015. Available online: https://www.dissercat.com/content/mezhdunarodnye-otnosheniya-v-regione-vostochnogo-sredizemnomorya-i-problema-transgranichnykh (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Semenova, T.; Al-Dirawi, A.; Al-Saadi, T. Environmental Challenges for Fragile Economies: Adaptation Opportunities on the Examples of the Arctic and Iraq. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL-Saadi, T.; Cherepovitsyn, A.; Semenova, T. Iraq Oil Industry Infrastructure Development in the Conditions of the Global Economy Turbulence. Energies 2022, 15, 6239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvoynikov, M.V.; Budovskaya, M.E. Development of a hydrocarbon completion system for wells with low bottomhole temperatures for conditions of oil and gas fields in Eastern Siberia. J. Min. Inst. 2022, 253, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvoynikov, M.V.; Kuchin, V.N.; Mintzaev, M.S. Development of viscoelastic systems and technologies for isolating water-bearing horizons with abnormal formation pressures during oil and gas wells drilling. J. Min. Inst. 2021, 247, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

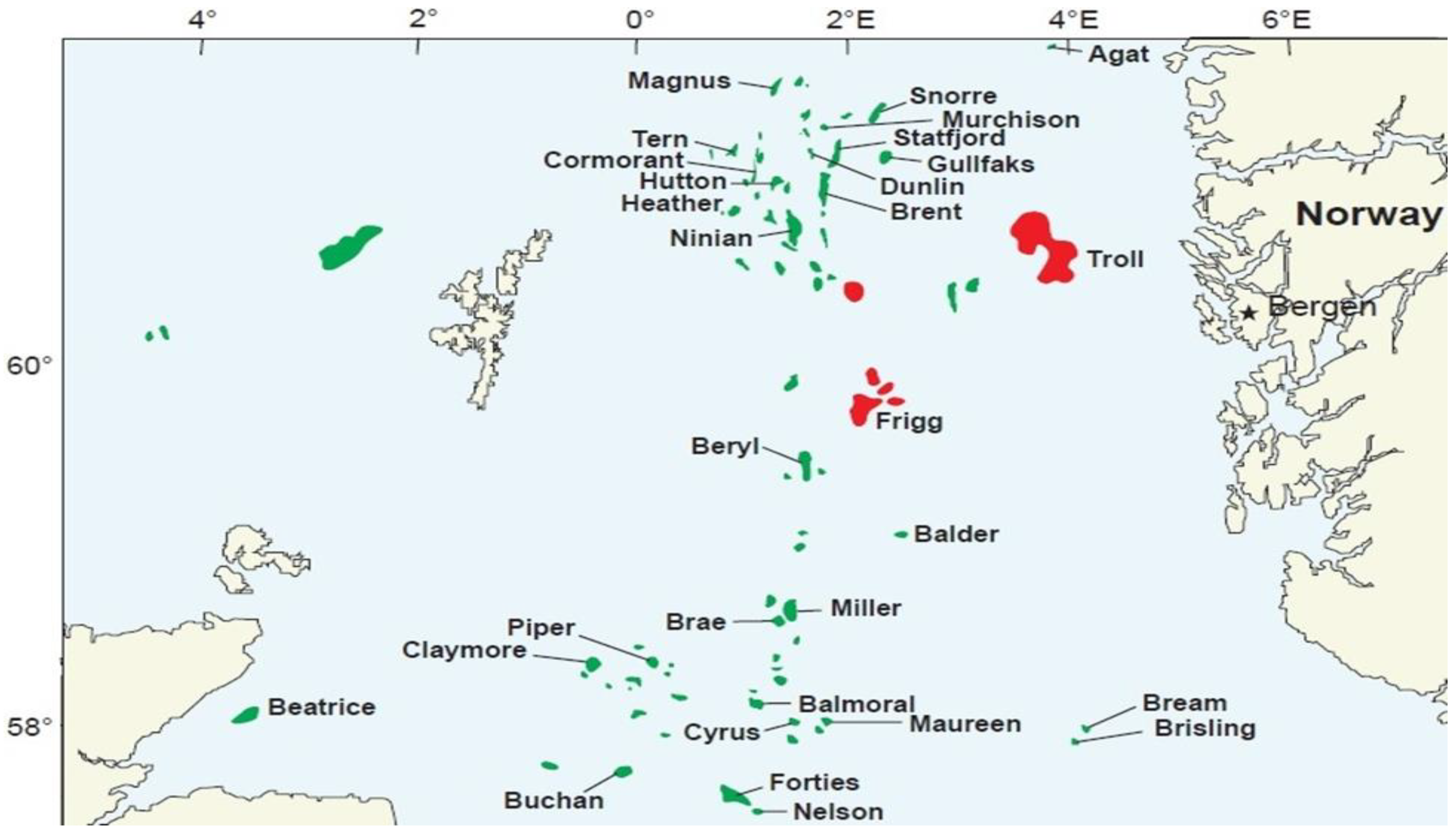

- Transboundary Frigg Deposit. Available online: https://wiki5.ru/wiki/Frigg_gas_field (accessed on 7 September 2022).

- Buckley, P.H.; Belec, J.; Anderson, A.D. Modeling Cross-Border Regions, Place-Making, and Resource Management: A Delphi Analysis. Resources 2017, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katysheva, E.G. Economic Problems of Oil and Gas Complex Development in the Northern Territories of Russia. Int. J. Adv. Manag. Econ. 2016, 5, 78–83. [Google Scholar]

- Timmerman, J.G. Building Resilience Through Transboundary Water Resources Management. In Palgrave Handbook of Climate Resilient Societies; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Water Framework Directive 2000/60/EU. 23 October 2000. Available online: http://caresd.net/iwrm/new/doc/direct.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2022).

- Ponomarenko, T.V.; Nevskaya, M.A.; Marinina, O.A. An Assessment of the Applicability of Sustainability Measurement Tools to Resource-Based Economies of the Commonwealth of Independent States. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Model Provisions for Transboundary Groundwaters. UN, New York and Geneva. 2014. Available online: https://unece.org/DAM/env/water/publications/WAT_model_provisions/ece_mp.wat_40_eng.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Golovina, E.I.; Grebneva, A.V. Management of groundwater resources in transboundary territories (on the example of the Russian Federation and the Republic of Estonia). J. Min. Inst. 2021, 252, 788–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martirosyan, A.V.; Ilyushin, Y.V.; Afanasieva, O.V. Development of a Distributed Mathematical Model and Control System for Reducing Pollution Risk in Mineral Water Aquifer Systems. Water 2022, 14, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedeva, Y.A.; Kotiukov, P.V.; Lange, I.Y. Study of the geo-ecological state of groundwater of metropolitan areas in the conditions of intensive contamination thereof. J. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 21, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shestakov, A.K.; Petrov, P.A.; Nikolaev, M.Y. Automatic system for detecting visible outliers in electrolysis shop of aluminum plant based on technical vision and a neural network. Metallurgist 2022, 10, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zohud, A.; Alam, L.A. Review of Groundwater Contamination in West Bank, Palestine: Quality, Sources, Risks, and Management. Water 2022, 14, 3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandhi, A.; Karunanidhi, D.; Sankar, M.; Panda, S.; Kannan, N. A Framework for Sustainable Groundwater Management. Water 2022, 14, 3416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvinenko, V.S. Digital Economy as a Factor in the Technological Development of the Mineral Sector. Nat. Resour. Res. 2019, 28, 1–21. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11053-019-09568-4 (accessed on 19 August 2022). [CrossRef]

- Neal, M.J. COVID-19 and water resources management: Reframing our priorities as a water sector. Water Int. 2020, 45, 435–440. [Google Scholar]

| Similarities | Differences |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Golovina, E.; Shchelkonogova, O. Possibilities of Using the Unitization Model in the Development of Transboundary Groundwater Deposits. Water 2023, 15, 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15020298

Golovina E, Shchelkonogova O. Possibilities of Using the Unitization Model in the Development of Transboundary Groundwater Deposits. Water. 2023; 15(2):298. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15020298

Chicago/Turabian StyleGolovina, Ekaterina, and Olga Shchelkonogova. 2023. "Possibilities of Using the Unitization Model in the Development of Transboundary Groundwater Deposits" Water 15, no. 2: 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15020298

APA StyleGolovina, E., & Shchelkonogova, O. (2023). Possibilities of Using the Unitization Model in the Development of Transboundary Groundwater Deposits. Water, 15(2), 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/w15020298