Comprehensive Analysis of Transient Flow Pattern and Radial Force Characteristics Within Centrifugal Pumps Under Variable Frequency Speed Regulation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

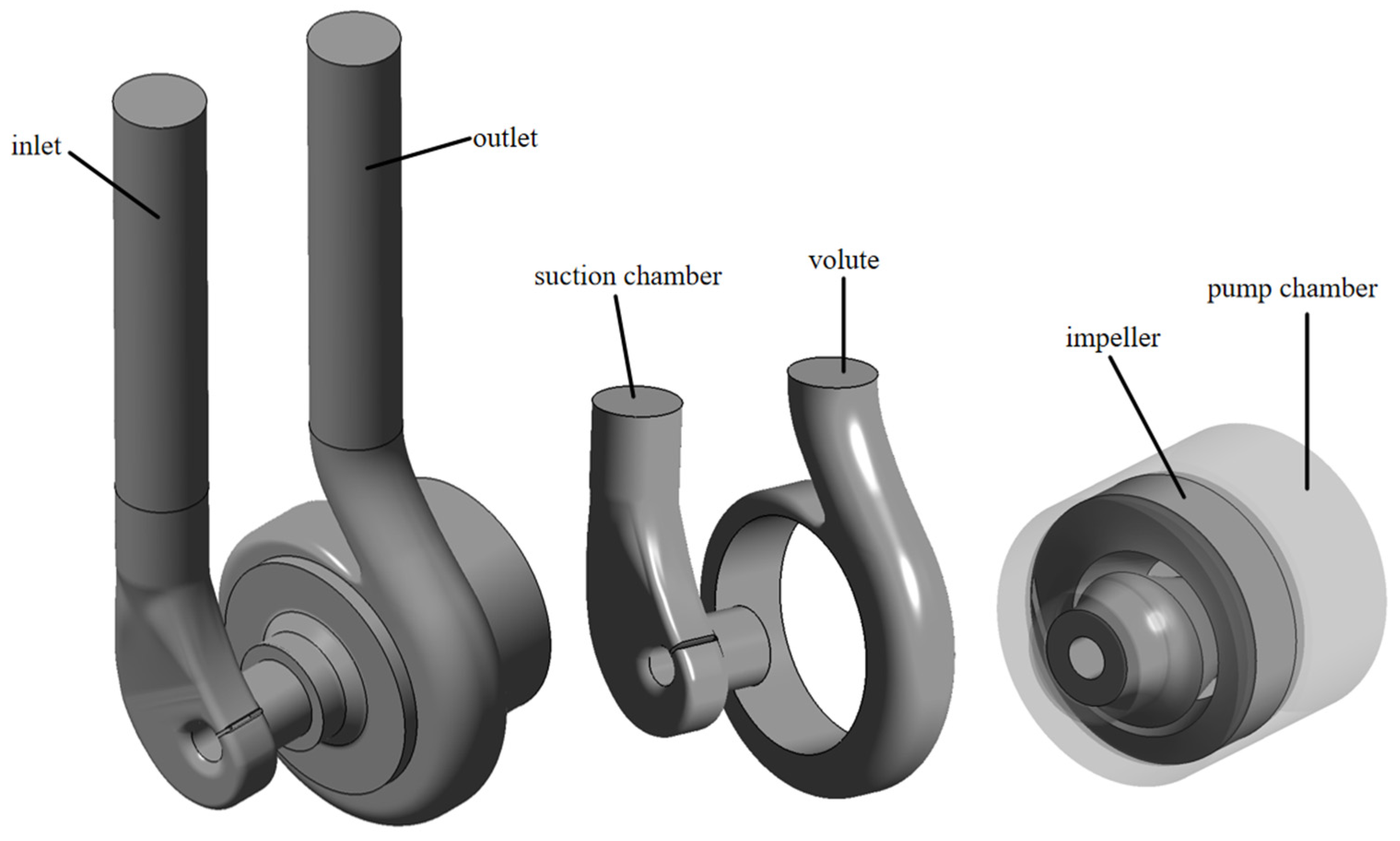

2. Pump Model and Numerical Simulation Method

2.1. Calculation Model

2.2. Grid Division and Independence Test

2.3. Flow Control Equation

2.4. Numerical Simulation Method

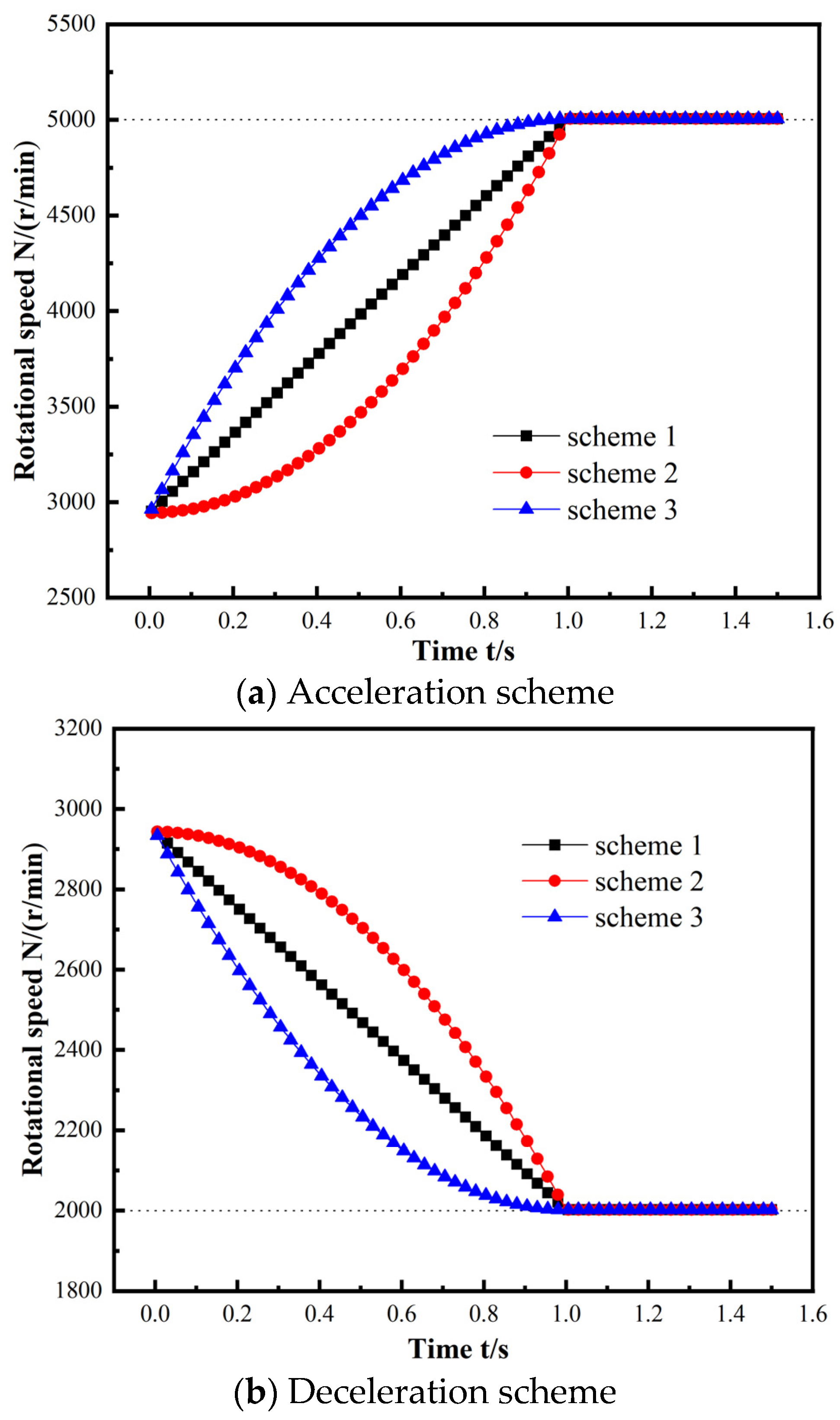

2.4.1. Speed Sudden Change Scheme

2.4.2. Numerical Scheme

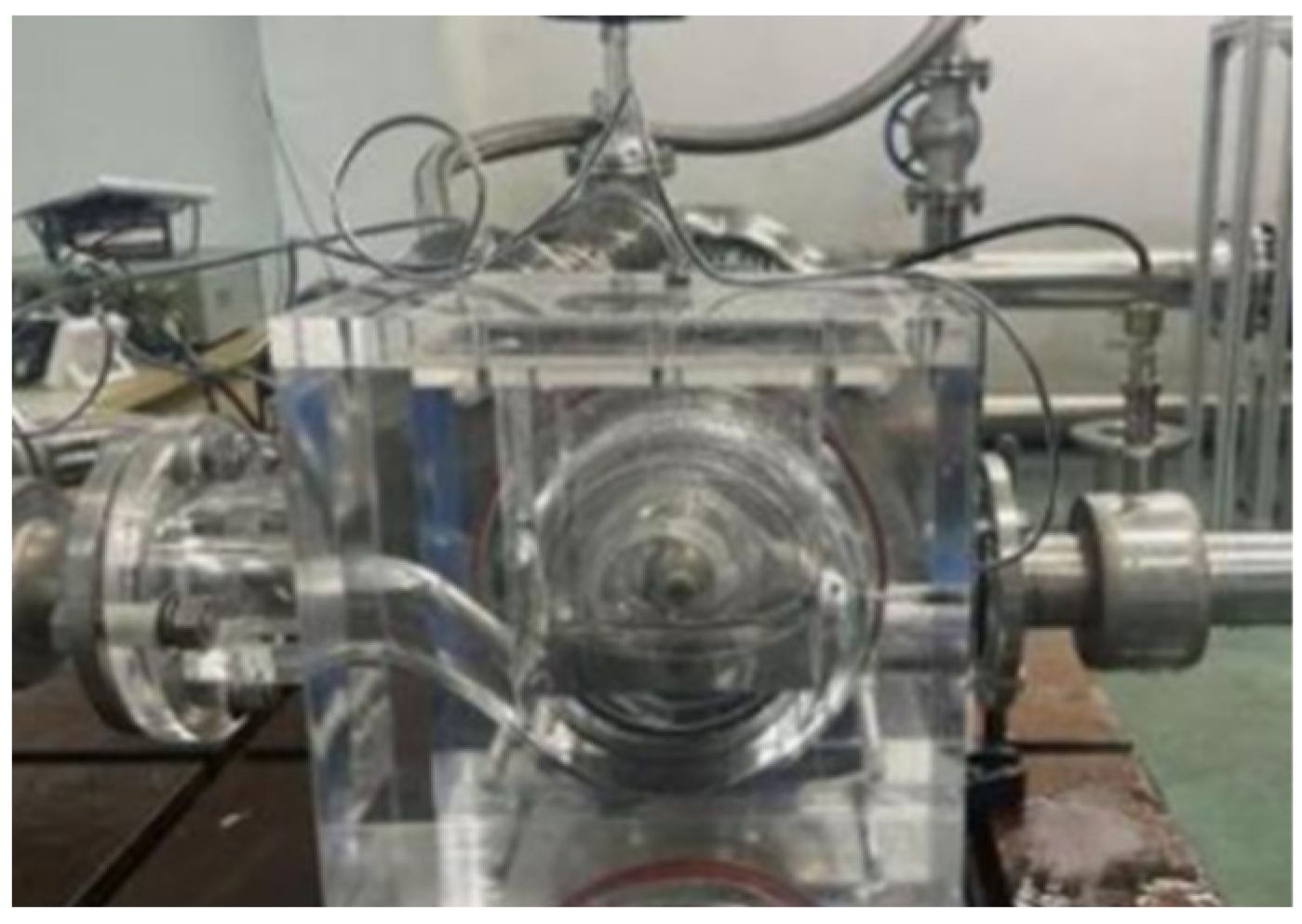

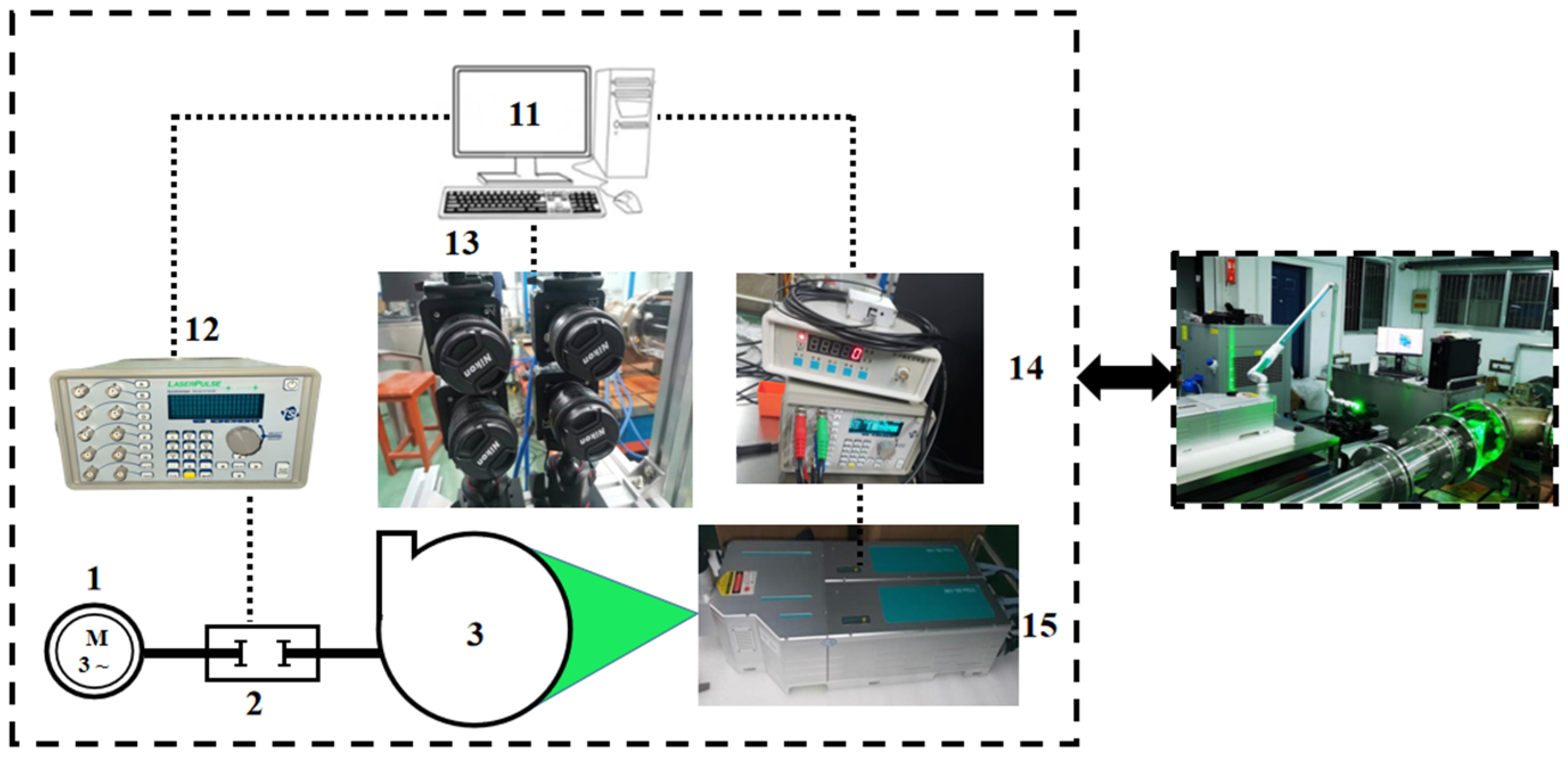

3. Test Verification

3.1. Test System

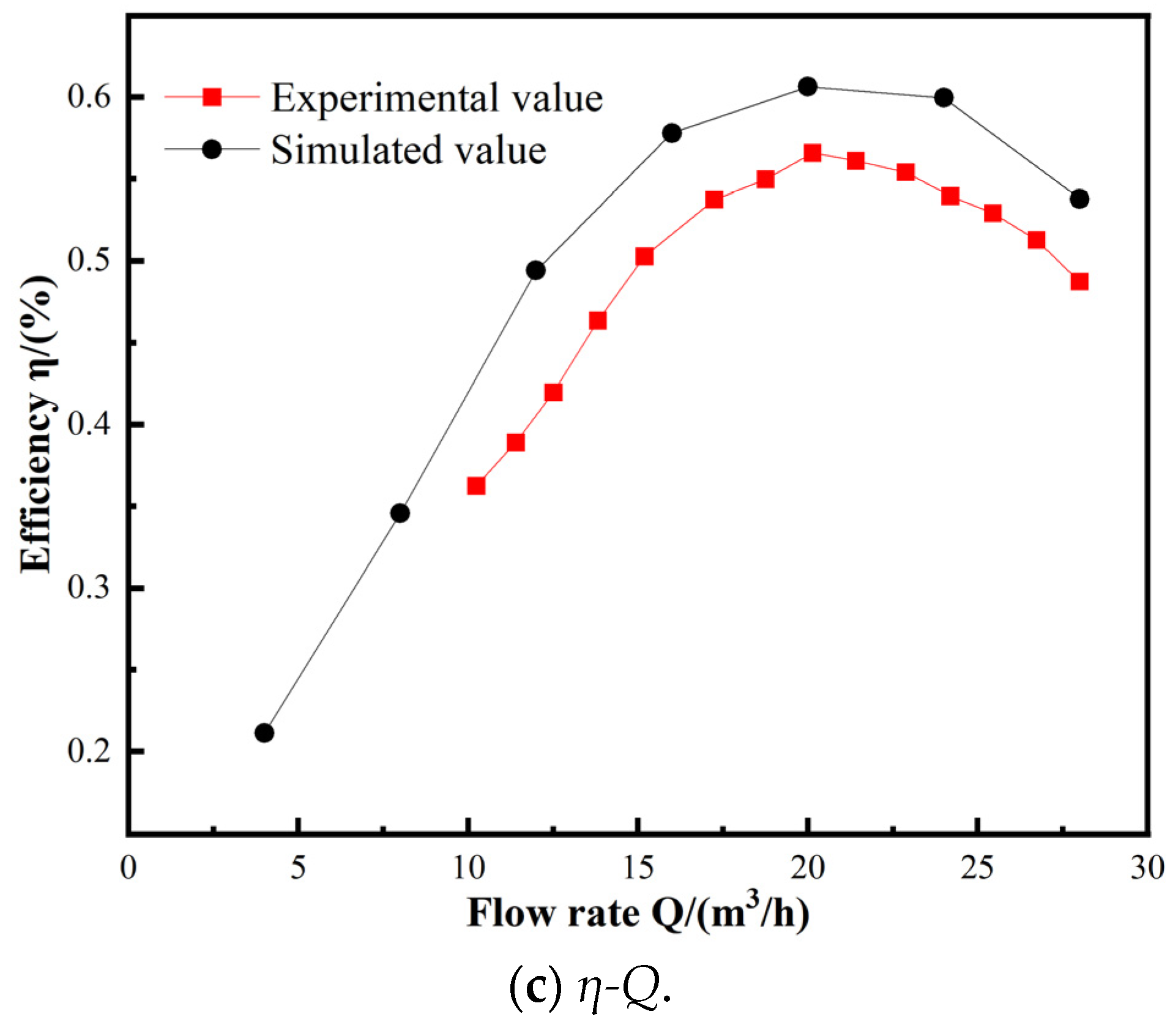

3.2. Test Results of External Characteristics

3.3. PIV Test Results

4. Results and Discussion

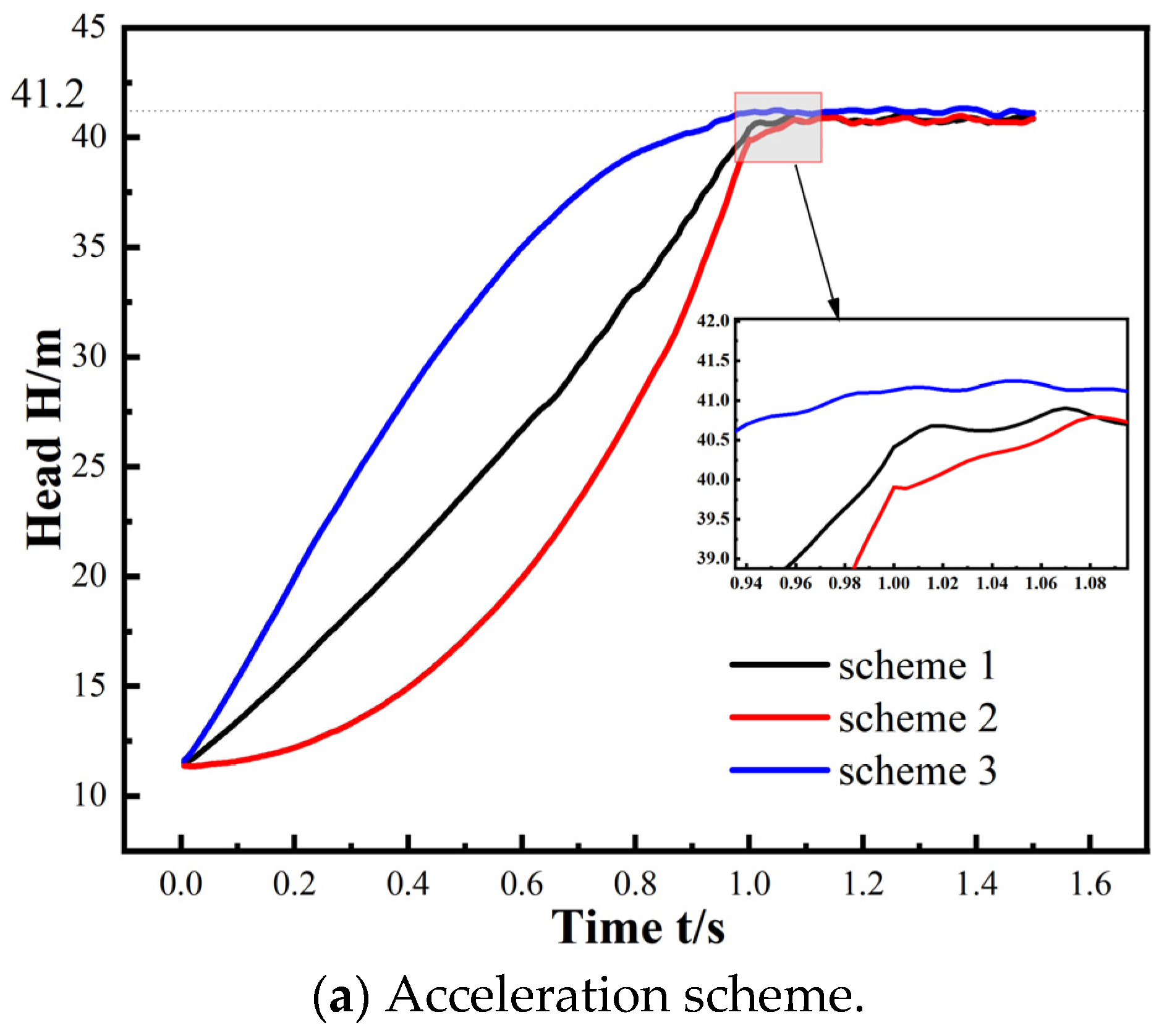

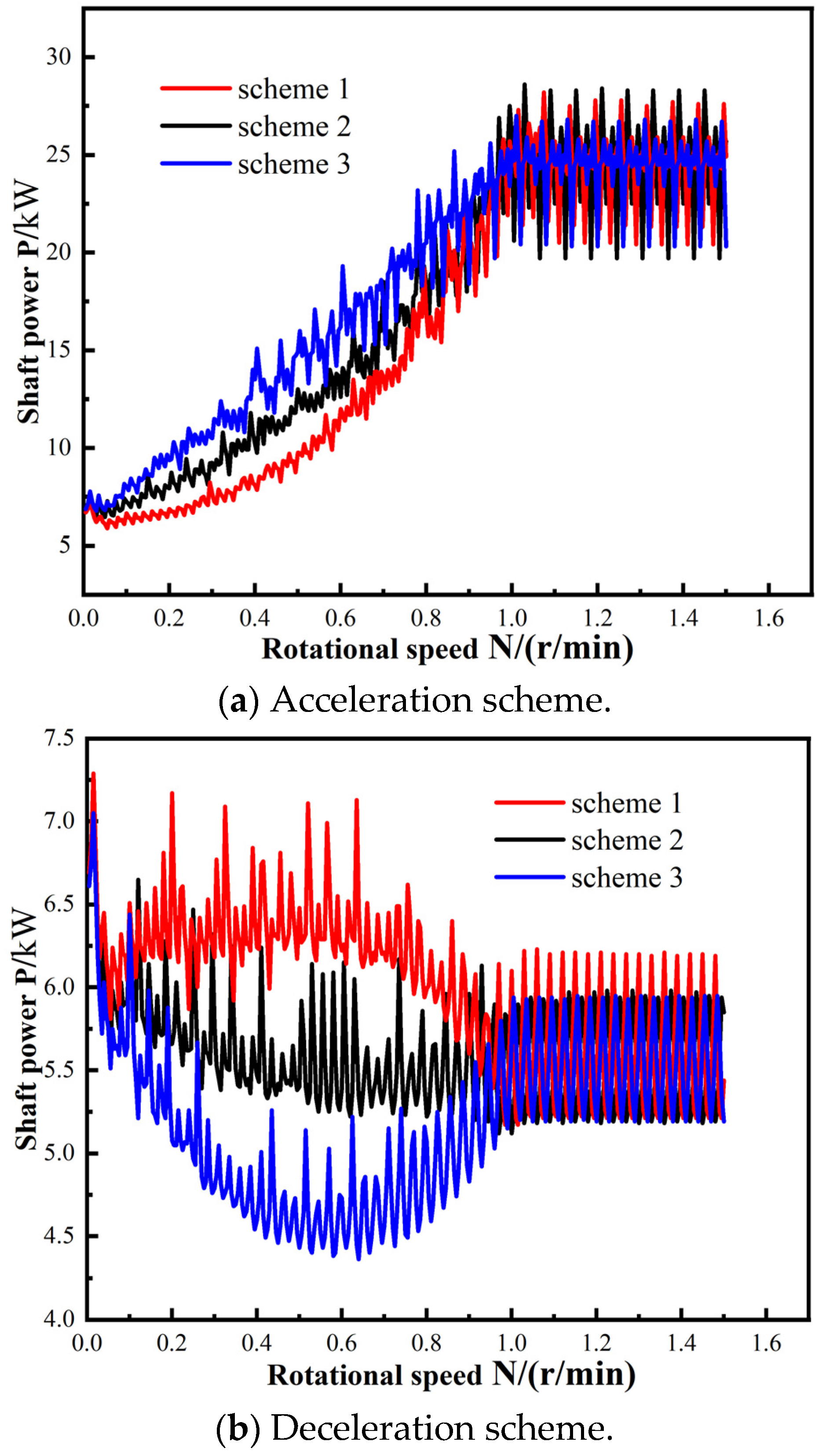

4.1. Transient External Characteristics

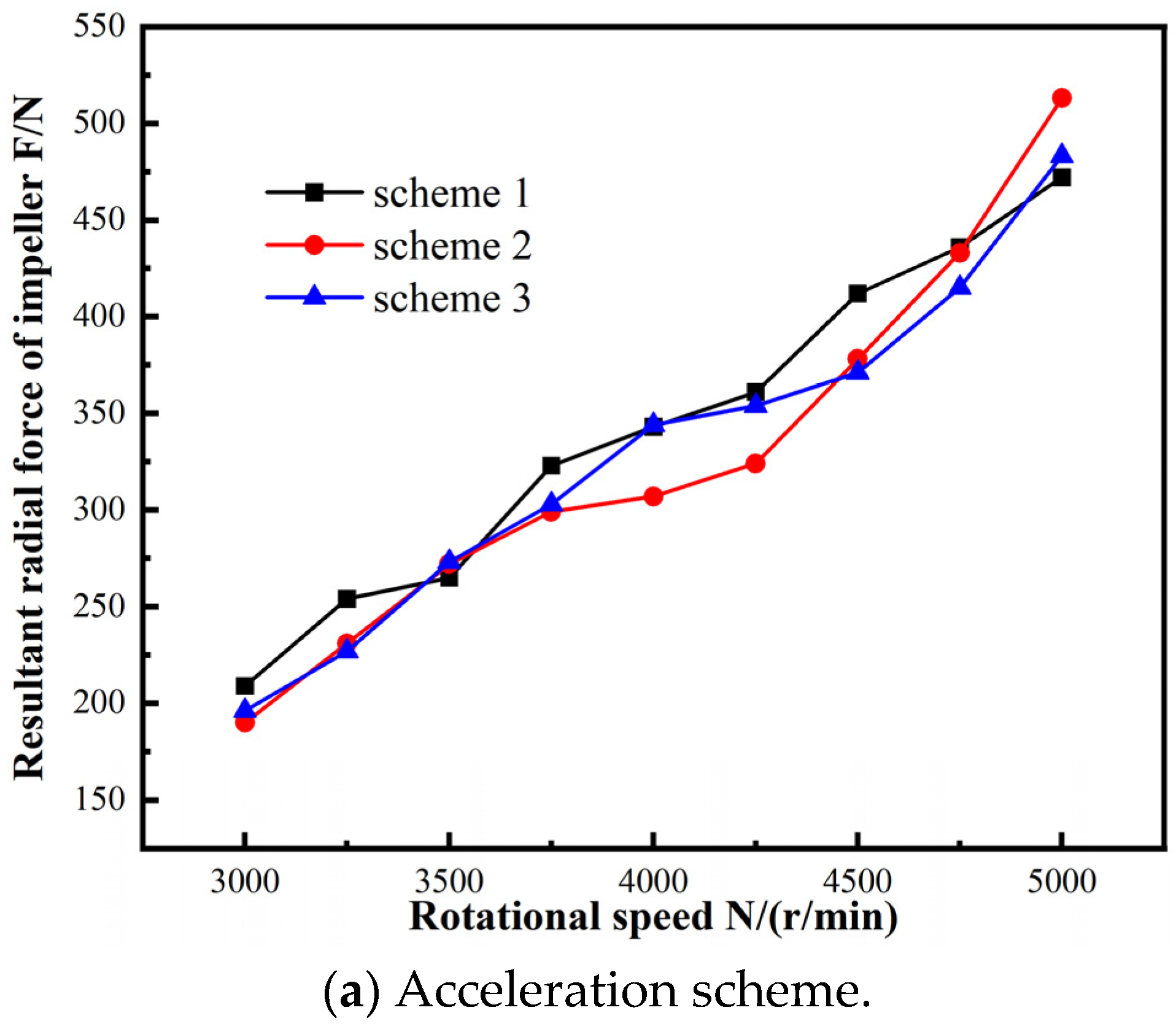

4.2. Radial Force on Impeller During Variable Speed

+force_x()@Impeller_Blades+force_x()@Interface1+force_x()@Interface2

+force_y()@Impeller_Blades+force_y()@Interface1+force_y()@Interface2

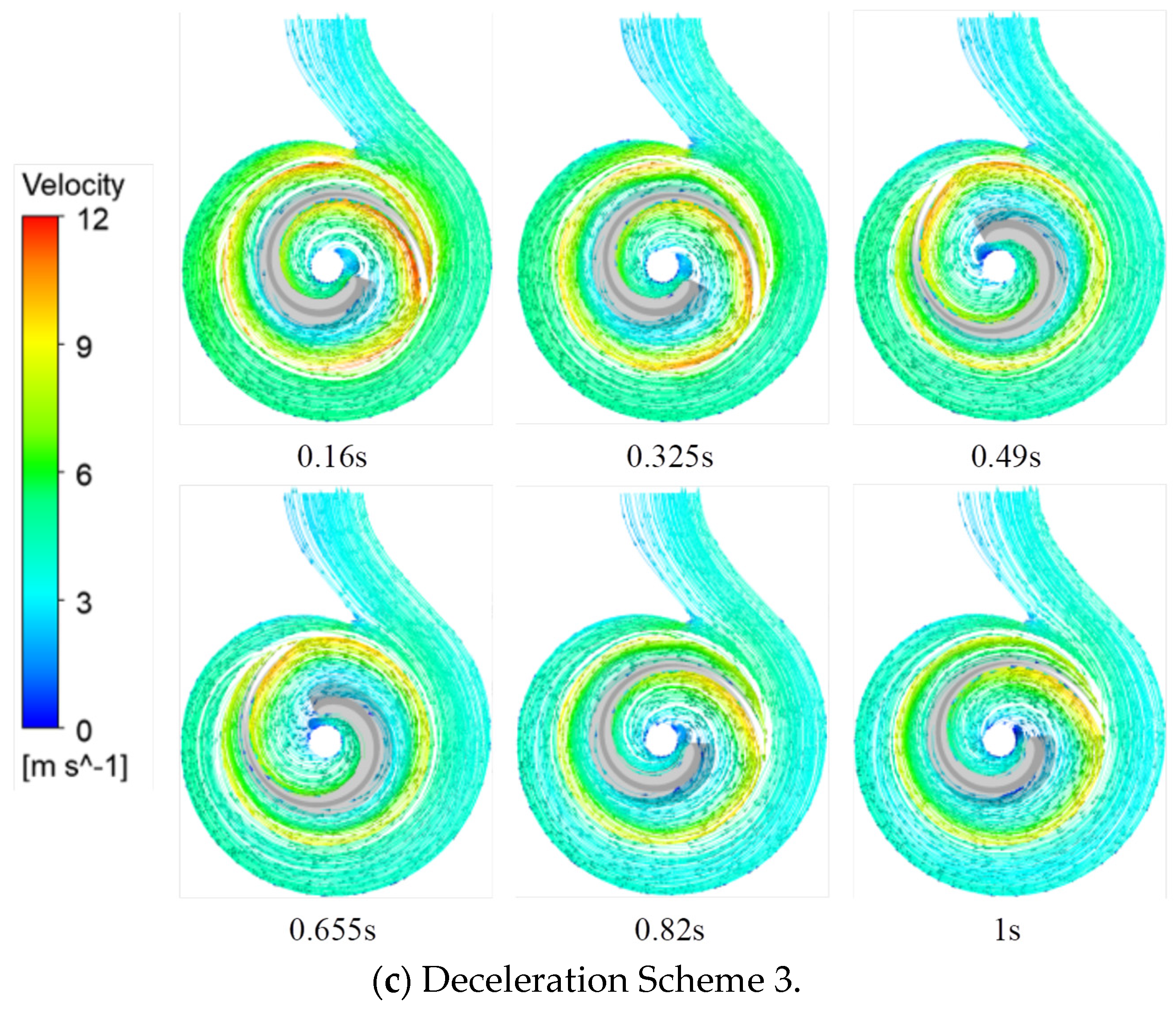

4.3. Internal Flow Field Characteristics in Variable Speed Process

4.3.1. Pressure Field Distribution

4.3.2. Flow Field Distribution

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, Y.; Li, X.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, X.; Lin, T.; Cao, H. An energy consumption improvement method for centrifugal pump based on bionic optimization of blade trailing edge. Energy 2022, 246, 123323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W. Status Analysis of agricultural irrigation pumping station (group) and energy-saving countermeasures. Drain. Irrig. Mach. 1988, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Huang, X.; Li, D. Research on hydraulic performance of vertical outlet channel in large submersible pump station. China Water Supply Drain. 2018, 34, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar, V.K.A.; Umashankar, S.; Paramasivam, S.; Hanigovszki, N. A comprehensive review on energy efficiency enhancement initiatives in centrifugal pumping system. Appl. Energy 2016, 181, 495–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, H.; Ohashi, H. Transient characteristics of a centrifugal pump during starting period. J. Fluids Eng. 1982, 104, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, H.; Yoneda, H.; Sagara, K. The response of a centrifugal pump to fluctuating rotational speed. J. Fluids Eng. 1995, 117, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, R.J.; Barker, W.P. Centrifugal pump performance during transient operation. J. Fluids Eng. 1995, 117, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Huang, Y.; Ji, L.; Ma, L.; Agarwal, R.K.; Awais, M. Prediction model for energy conversion characteristics during transient processes in a mixed-flow pump. Energy 2023, 271, 127082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanapandi, P.; Prasad, R. Centrifugal pump transient characteristics and analysis using the method of characteristics. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 1995, 37, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanapandi, P.; Prasad, R. A Qoptuasi-steady performance prediction model for dynamic characteristics of a volute pump. Proceeding Inst. Mech. Eng. Part A J. Power Energy 1994, 208, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Jiao, L.; Wang, L. Experimental study on transient hydraulic performance of centrifugal pump under different starting acceleration. J. Eng. Thermophys. 2008, 29, 62–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Wu, D.; Wang, L. Transient Hydraulic characteristics of centrifugal Pump during rapid start-up process—External characteristics study. J. Zhejiang Univ. Eng. Ed. 2005, 39, 605–608. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Wu, D. Development of transient performance Test System for centrifugal Pump during rapid start-up. Acta Metrol. Sin. 2005, 26, 159–162. [Google Scholar]

- Ping, S.; Wu, D.; Wang, L. Transient Effect Analysis of Centrifugal Pump during rapid opening. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Eng. Technol.) 2007, 41, 112–115. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Cui, B.; Li, Y.; Dou, H. Experimental study on rapid start-up process of centrifugal pump. J. Eng. Thermophys. 2013, 34, 2056–2060. [Google Scholar]

- Brennen, C.E.; Acosta, A.J. Fluid-induced rotordynamic forces and instabilities. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2006, 13, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Yu, D.; Wang, Y.; Shi, J.; Gan, B. Research on the fluid-induced excitation characteristics of the centrifugal pump considering the compound whirl effect. Facta Univ. Ser. Mech. Eng. 2023, 21, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baun, D.O. Effect of Relative Impeller-to-Volute Position on Hydraulic Efficiency and Static Radial Force Distribution in a Circular Volute Centrifugal Pump. J. Fluids Eng. 2000, 122, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boehning, F.; Timms, D.L.; Amaral, F.; Oliveira, L.; Graefe, R.; Hsu, P.; Schmitz-Rode, T.; Steinseifer, U. Evaluation of Hydraulic Radial Forces on the Impeller by the Volute in a Centrifugal Rotary Blood Pump. Artif. Organs 2011, 35, 818–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadab, M.; Karimipour, M.; Najafi, A.F.; Paydar, R.; Nourbakhsh, S.A. Effect of impeller shroud trimming on the hydraulic performance of centrifugal pumps with low and medium specific speeds. Eng. Appl. Comput. Fluid Mech. 2022, 16, 514–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benra, F.K. Numerical and experimental investigation on the flow induced oscillations of a single-blade pump impeller. J. Fluids Eng. 2006, 128, 783–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, Y.; Fukutomi, J. Effect of impeller outlet width on radial thrust of single-blade centrifugal pump with a helical spiral suction flow channel. Turbomachinery 2011, 39, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Nishi, Y.; Fukutomi, J. Effect of blade outlet angle on unsteady hydrodynamic force of closed-type centrifugal pump with single blade. Int. J. Rotating Mach. 2014, 4, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Chen, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Li, G. Numerical Simulation Study on the influence of half-height guide vane on the excited force of centrifugal pump. J. Vib. Shock 2019, 38, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Ye, L.; Yuan, S.; Yuan, Y. Effect of shunt blade on Vibration Force Characteristics of centrifugal Pump. J. Agric. Mech. Res. 2013, 35, 181–185. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, J.; Lin, L.; Zhang, S.; Gan, J.; Shi, H.; Wang, S.; Fan, W. Design and Research of a New type radial Force balancing device for centrifugal Pump. China Rural Water Resour. Hydropower 2013, 147–150. [Google Scholar]

- Mou, J.; Liu, J.; Zheng, S.; Gu, Y.; Dai, D.; Ma, Y. Single or double every tongue radial force characteristics and internal flow field of centrifugal pump. Influ. Vib. Shock 2016, 35, 116–122. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, X.; Xu, B.; Ye, X.; Liu, H. Influence of guide vane circumferential Position on Radial Force of core main pump impeller. J. Lanzhou Univ. Technol. 2018, 44, 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Shi, W.; Van Esch, B.P.M.; Shi, L.; Dubuisson, M. Numerical and experimental investigation of tip leakage vortex trajectory and dynamics in an axial flow pump. Comput. Fluids 2015, 112, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraisamy, K.; Iaccarino, G.; Xiao, H. Turbulence modeling in the age of data. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2019, 51, 357–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Lai, X.; Chen, X.; Liu, X.; Song, D. Radial Force Characteristics of impeller during Variable frequency speed regulation of Double suction centrifugal Pump. J. Drain. Irrig. Mach. Eng. 2024, 42, 757–763. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Y.; An, C.; Zhu, R.; Chen, J. Research on hydrodynamics of high velocity regions in a water-jet pump based on experimental and numerical calculations at different cavitation conditions. Phys. Fluids 2021, 33, 045124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, K.; Huang, B.; Miao, H.; Shi, P.; Wu, D. Quantitative analysis of energy loss and vibration performance in a circulating axial pump. Energy 2022, 243, 122753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oro JM, F.; Perotti, R.B.; Vega, M.G.; González, J. Effect of the radial gap size on the deterministic flow in a centrifugal pump due to impeller-tongue interactions. Energy 2023, 278, 127820. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Tang, F. Investigation on hydrodynamic characteristics of coastal axial flow pump system model under full working condition of forward rotation based on experiment and CFD method. Ocean Eng. 2022, 253, 111286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; He, X.; Shi, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Qiu, N. Numerical study on pressure fluctuation of a multistage centrifugal pump based on whole flow field. AIP Adv. 2019, 9, 035118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, K.W.; Lee, T.S.; Winoto, S.H.; Zhao, Z.M. Numerical Flow Simulation in a Centrifugal Pump at Design and Off-Design Conditions. Int. J. Rotating Mach. 2007, 2007, 083641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Geng, C.; Luo, X. Unstable flow characteristics in vaneless region with emphasis on the rotor-stator interaction for a pump turbine at pump mode using large runner blade lean. Renew. Energy 2022, 185, 1343–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Design Parameter | Parameter Value |

|---|---|

| Design flow rate (m3/h) | 20 |

| Design head (m) | 11 |

| Suction chamber inlet diameter | 50 |

| Suction chamber outlet diameter | 45 |

| Rated speed n (r/min) | 2940 |

| Impeller inlet diameter D0 (mm) | 45 |

| Impeller outlet diameter D1 (mm) | 125 |

| Blade outlet width | 30 |

| Blade outlet setting angle (°) | 18 |

| Blade angle (°) | 360 |

| Computational Domain | Part | Grid Size | Grid Number |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inlet | Static domain | 1 mm | 83,328 |

| Suction chamber | Static domain | 1 mm | 1,395,241 |

| Impeller | Rotation domain | 2 mm | 222,494 |

| Pump chamber | Static domain | 1 mm | 516,681 |

| Volute | Static domain | 1 mm | 165,769 |

| Outlet | Static domain | 1 mm | 107,136 |

| Rotational Speed (r/min) | Steady State | Accelerated Scheme 1 | Accelerated Scheme 2 | Accelerated Scheme 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2940 | 136 | 209 | 190 | 196 |

| 4000 | 221 | 343 | 307 | 344 |

| 5000 | 449 | 472 | 513 | 483 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tan, L.; Niu, J.; Shi, W.; Zhao, M.; Gao, S.; Yang, Y.; Zuo, Z.; Wang, T.; Li, H. Comprehensive Analysis of Transient Flow Pattern and Radial Force Characteristics Within Centrifugal Pumps Under Variable Frequency Speed Regulation. Water 2025, 17, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17010056

Tan L, Niu J, Shi W, Zhao M, Gao S, Yang Y, Zuo Z, Wang T, Li H. Comprehensive Analysis of Transient Flow Pattern and Radial Force Characteristics Within Centrifugal Pumps Under Variable Frequency Speed Regulation. Water. 2025; 17(1):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17010056

Chicago/Turabian StyleTan, Linwei, Jianxun Niu, Weidong Shi, Miaomiao Zhao, Song Gao, Yang Yang, Zilei Zuo, Tao Wang, and Hui Li. 2025. "Comprehensive Analysis of Transient Flow Pattern and Radial Force Characteristics Within Centrifugal Pumps Under Variable Frequency Speed Regulation" Water 17, no. 1: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17010056

APA StyleTan, L., Niu, J., Shi, W., Zhao, M., Gao, S., Yang, Y., Zuo, Z., Wang, T., & Li, H. (2025). Comprehensive Analysis of Transient Flow Pattern and Radial Force Characteristics Within Centrifugal Pumps Under Variable Frequency Speed Regulation. Water, 17(1), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17010056