Abstract

Foreign capital has dominated over half of the public–private partnership (PPP) projects in developing countries over the past three decades. As such, attracting and regulating foreign participation in water PPP projects presents a critical challenge for both practitioners and scholars. Using a dataset of 2024 water PPP projects from 1994 to 2021, this study investigates foreign participation and its fall in China’s water PPP projects. Our findings highlight three key points: First, the proportion of projects undertaken by foreign capital decreased from 100% to less than 0.5%, with Chinese domestic capital taking its place. Second, resource dependence on foreign capital and the local government’s need for control lead to four types of foreign participation: financing water plants under user-pays, financing and operating water utilities under government-pays, participating with mainly an O&M role, and nearly no participation. Third, a better balance between efficiency gains and control needs via cooperation with domestic capital by local governments had driven the decline in foreign participation. This study makes two key contributions: (1) it is one of the pioneer studies on systematically tracing the evolution of foreign participation in PPP projects, and (2) it explains the fall of foreign participation from a local government perspective, complementing market-based explanations.

1. Introduction

A public–private partnership (PPP) can be defined as “a cooperative agreement where public sector bodies enter into long-term contractual agreements in which private parties participate in, or provide support for the provision of infrastructure and public service” [1]. Developing countries are looking at PPP as an option to deal with the poor water supply, sanitation services, and constrained budgets [2]. On the one hand, foreign capital has dominated over half of the water PPP projects in developing countries over the past three decades. According to the World Bank’s Private Participation in Infrastructure (PPI) database (see Appendix A List 1), the proportion of foreign participation in water PPP projects in developing countries surged to 70% in the 1990s, declined to approximately 30% around 2010, and has since gradually increased and stabilized around 50%. On the other hand, foreign participation has a negative effect on project survival. Water PPP projects, characterized by a large initial fixed cost, regulatory difficulties, high sunk costs, and multiple, and sometimes, conflicting public policy objectives [3,4], are viewed as risky investments, especially in developing countries [5]. Foreign participation further increases the risks, with many failure cases all around the world [6,7]. Therefore, attracting and regulating foreign participation in water PPP projects is an essential challenge for both practitioners and scholars.

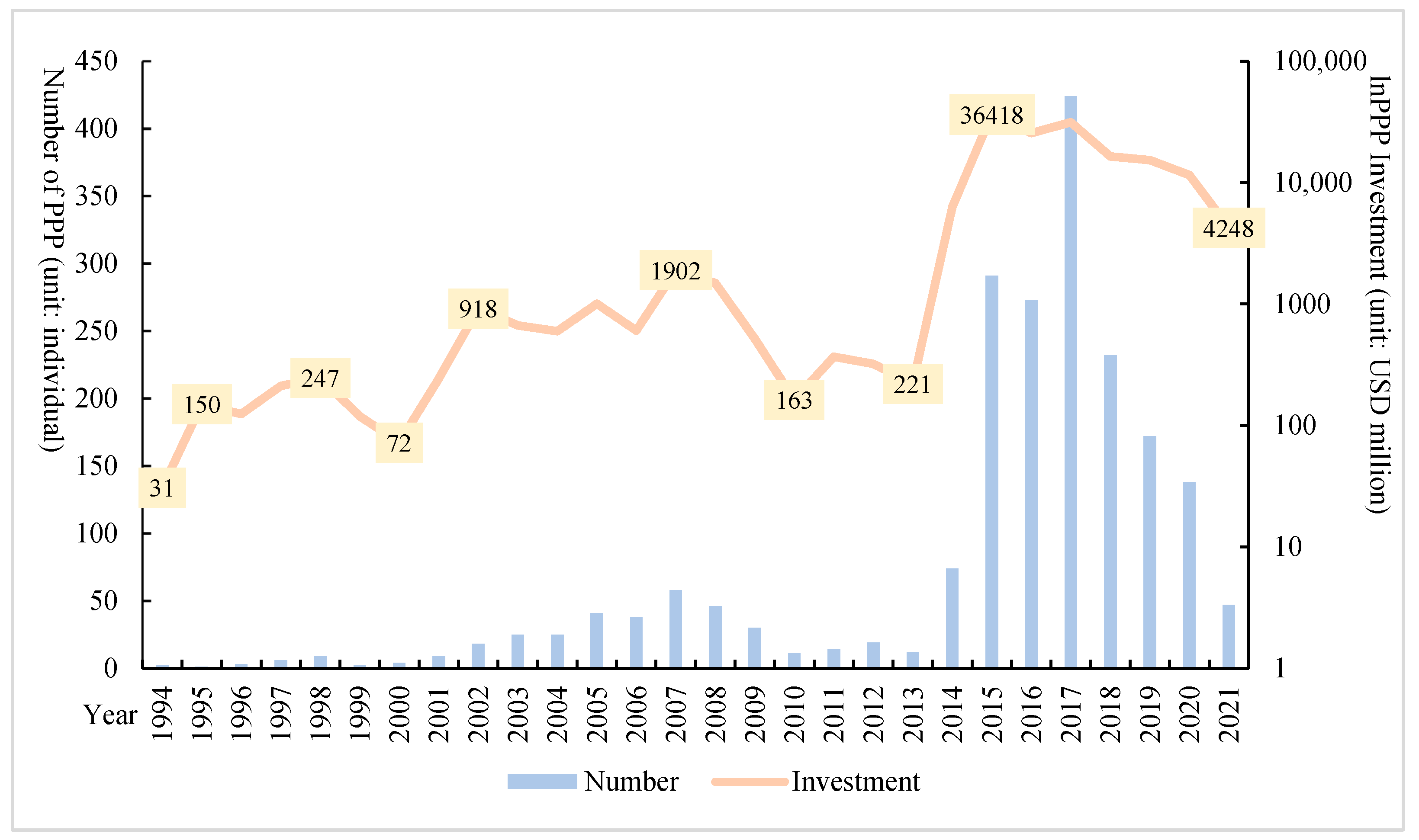

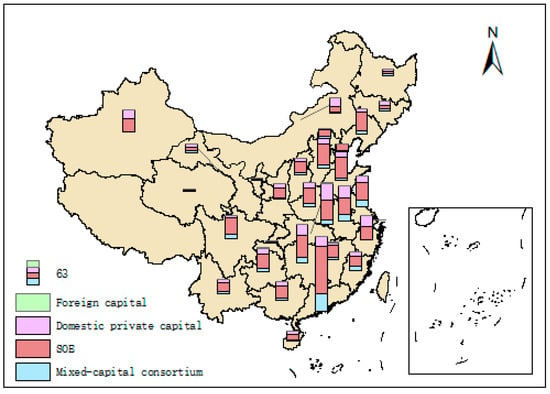

The long-lasting history of foreign participation in China’s water PPP development allows for a better understanding of what foreign participation in water PPP projects can and cannot possibly bring (see Figure 1). China is one of the countries with the highest PPP experience [8]. It has become the largest market for PPP in the water supply and sewerage sector in the world, enjoying a 61.89% share by volume of PPP projects and a 34.41% share by value in the last two decades [9]. Historically, foreign participation in China’s water PPP market has spanned over 30 years. China’s first water PPP project was launched in 1994 and was undertaken by Suez, a French multinational water enterprise. Since then, the Chinese government has opened its door for foreign investment and witnessed a boom of foreign investment in the water market in 1990s. However, foreign investment has fallen to the lowest level in recent decades, dropping sharply from 100% in 1994 to only 5% in 2018 [10,11]. From a typological perspective, foreign involvement takes various forms in China’s water supply and sanitation area, as it is not limited to BOT, TOT, joint venture, and O&M. In summary, China’s experiences of partnerships with foreign capital in the water PPP sector, both positive and negative, can offer valuable lessons for other developing countries, especially since China has made some costly mistakes along the way [12]. Therefore, the lessons learnt from foreign participation in China’s water PPP development can not only enhance our knowledge of transnational PPP projects and foreign participation as a critical success factor but also provide more practical insights for those eager to conduct business abroad and those thirsty for foreign investment but do not know how to run PPP projects.

Figure 1.

China’s water PPP development from 1994–2021.

The evolution of foreign participation in China’s water PPP development can also offer insights for other infrastructure areas. In 2021, 59% of investment volumes in developing countries were made by foreign capital [7]. Under the increasing levels of global economic integration, more and more PPP projects in the future, which are not limited to the water supply and sanitation sector, will be conducted between parties that cross national borders [13]. At the project level, many cross-border hydropower, dam, and irrigation projects are built and operated, particularly in developing countries, to meet their higher demand for electricity and fresh water [14,15]. At the country level, many countries are investing abroad. For example, the Chinese government issued the Belt and Road initiative in 2013, involving a large-scale expansion of infrastructure projects [16]. The Japanese government has been working on a policy called the “Japan and Emerging countries Co-creation Project” in recent years to facilitate its domestic enterprises to conduct business in emerging countries [17].

There has been rich research on China’s water PPP development and foreign participation, but less well understood is how the involvement of foreign investment proceeds and how its decline occurs. On the other hand, the existing explanations on the retreat of foreign participation ignore the role of the Chinese local government, which enjoys great autonomy in PPP employment under fiscal decentralization and administrative decentralization. Given the above background, the objectives of the paper are twofold:

- This paper seeks to make a historical track of foreign participation in China’s water PPP development;

- This paper seeks to explain foreign participation and its decline in China’s water PPP development from the government side.

This article investigates foreign participation and its decline in China’s water PPP development from the view of the local government. We first trace the process of private sector participation in China’s water PPP development from 1994 to 2021, noting the fact that foreign participation evolves from being a monopoly to being replaced by Chinese domestic capital. Drawing on resource dependence theory, we categorize foreign participation into four types and explain its decline under each category.

Our research makes several significant contributions. First, we provide a more systematic analysis of foreign participation history in relation to the private capital structure. By dividing private capital into foreign capital, domestic private capital, state-owned enterprise (SOE), and mixed-ownership consortium based on institutional links, the evolution of foreign participation and the partner choice of local government between foreign capital and domestic capital can be more clearly understood. Second, we form the typology of foreign participation in water PPP projects. By employing resource dependence theory and taking the efficiency incentives and control needs of the local government into account, we categorize foreign participation in China’s water PPP development into four types. Third, we ascribe foreign participation and its decline in China’s water PPP development to that of the Chinese local government, which needs to achieve a better balance between efficiency gains and control needs via cooperation with domestic capital. Our research findings also carry practical implications for foreign participation in PPP projects.

The paper is organized as follows. The next section reviews the literature on foreign-participated PPP projects, especially in the water supply and sanitation sector. The third section lays out the method and data. The fourth section traces China’s water PPP wave development and foreign participation in relation to the private capital structure. The fifth section further categorizes foreign participation into four types and explains its decline under each situation. The paper concludes with a discussion and recommendations for future studies.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Foreign Participation in PPP Projects

Foreign investment has a positive and significant impact on economic growth in developing countries [18,19]. A large fraction of foreign investment has gone into infrastructure fields through PPP arrangement, forming transnational PPP [20,21,22]. However, there exists a negative impact of foreign participation on the survival of PPP projects. In Asia and elsewhere, some large, high-profile, foreign-invested contracts have encountered difficulties [23,24,25]. Many foreign-participated PPP projects in China, Mexico, Ghana, and Argentina experienced early termination [6,7].

Foreign capital will only emerge as PPP partners when the benefits outweigh the economic and political costs [26]. Market size is a critical determinant, and the institutional quality mostly matters for the decision to invest [27], but risk factors, including local legal risk, cooperation risk, tariff risk, and political risk as the most frequently identified ones [21], would reduce foreign investment in developing countries [28,29]. However, the governance environment, such as the regulatory quality, the rule of law, political stability, and the control of corruption, can moderate the risk assumed by foreign capital [7,30].

Foreign participation in water areas can typically reflect the above logic. Foreign participation in water PPP projects in developing countries begins high and ends low. Foreign companies are involved in the first-time adoption of a PPP model in water areas in many developing Asian countries [31]. However, domestic companies are playing an increasingly important role over the recent decade, while foreign investments fell significantly [10,32]. China is such a typical case. Numerous foreign companies had retreated from China’s water PPP market since 2008 [33]. There are two explanations. The “risk aversion explanation” puts forward that foreign capital chose to leave because it has high risk perception due to the nature of PPP projects and specific legal and regulatory restrictions [11,33,34], and the “substitution explanation” argues that foreign capital is replaced by local Chinese companies [5,31,35,36]. In comparison to foreign investors, domestic investors are more adaptive in handling political risks due to the knowledge of local cultures and needs as well as the ability to manage relationships with local government counterparts [37]. Against the massive retreat, there are still a few active foreign market players investing heavily in China’s water market, such as Veolia and Suez, two French multinational water companies [38]. It is found that they adopted an effective risk mitigation strategy by forming joint ventures with local municipal water authorities that have political influence rather than sectoral expertise [33,39], but their rate of making new investments was rather low [40].

2.2. Rationale for Public Sector Partnerships with Foreign Capital

Transnational PPP involves long-term cooperations between public and foreign private sector firms [21,41]. The public sector selects a foreign private partner for its financial resources and operational capacities but may turn to domestic capital under social protest and the need for control. Foreign capital has advantages in terms of innovation capacity, talent pools, and financial resources compared to local firms in the host country [7,42]. When public utilities have low and high levels of infrastructure PPP experience and the infrastructure project is highly leveraged, they tend to partner with foreign private sector firms [41]. However, the liability of foreignness borne by foreign private capital firms due to unfamiliarity in the geography, the supply chain, the local legislation, and the business practice [43], together with the government’s preference for local control of infrastructure projects and public protest [13,26,44], would deter the public sector from partnering with foreign capital.

In the water supply and wastewater sector, the public sector employs PPP to release its fiscal pressure and meet its efficiency improvement needs. First, serious financing difficulties, faced by local government resulting from increasing demand, aging infrastructure, and declining revenues, take clear precedence over other considerations when employing PPP [45,46,47]. For example, the low degree of financial capacity has caused the Shanghai government to invite foreign water enterprises via BOT schemes, joint ventures, and equity sales [48]. Second, PPP is often employed to bring in ample resources, competent business, technical staff, operation expertise, and to further enhance performance through the initiation of benchmarking [49]. In addition, political incentives stemming from socio-economic pressures also increase the possibility of partnering with foreign capital [47].

To summarize, the existing research on foreign participation in water PPP projects has three limitations. Firstly, despite the long-lasting and broad foreign participation in water PPP projects and the fact that foreign participation has been justified as a critical success factor for PPP employment [7,13,41], systematic research on the evolution and impact of foreign participation in PPP is not enough. There has been rich literature on foreign direct investment in developing countries. But the PPP model, accompanied with long-term incomplete contracts and the bundle of construction and operation together [50], turns out to be more complex than the typical FDI context [13].

Secondly, the existing research overemphasizes the characteristics of the foreign private sector firm without fully recognizing that the local government also has a choice in partner and PPP model selection. Foreign participation involves substantial interactions with local governments in the host country [51]. The local government and other stakeholders in the host country can exert pressure on foreign capital in different ways [52]. This can be typical in developing countries characterized by weak institutional and technical capacities and a high level of information asymmetry [53].

Thirdly, most descriptive analyses do not take SOE-led water PPP projects into calculation when evaluating China’s water PPP development due to PPP definition and database restrictions. The two most commonly used databases, one is the World Bank’s PPI database and the other is the Project Finance International (PFI) database, do not consider a domestic state-owned enterprise as a private entity. However, dubbed as “collaboration between the government and societal capital (see Appendix A List 2)”, China’s PPP projects attract investments not only from private enterprises but also from SOEs [54]. As reported by the PPP Center of the Ministry of Finance, the number and total amount of PPP projects taken by SOEs in 2022 accounted for 95.67% and 80.88%, respectively. Taking SOE-led water PPP projects into calculation can not only correct the underestimation of China’s water PPP market but also better explain the retreat of foreign participation in China’s water market.

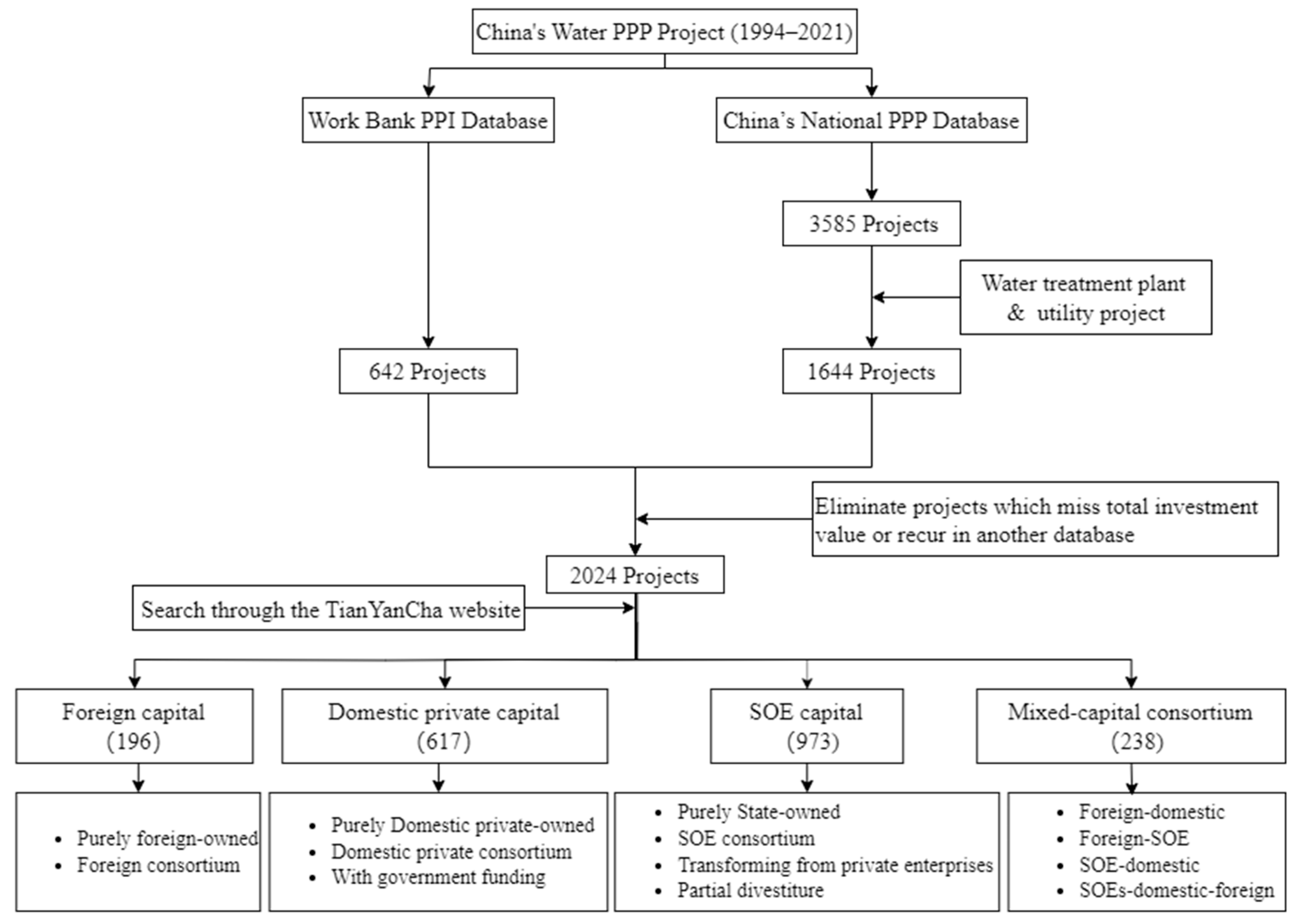

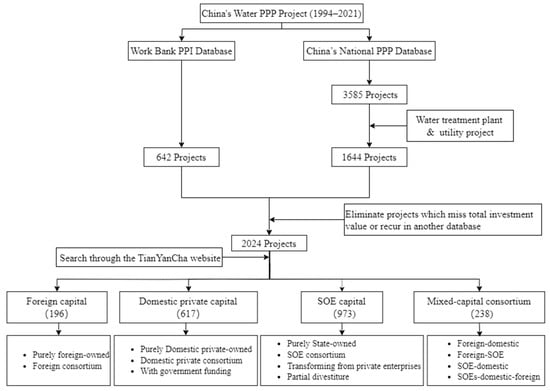

3. Methodology

This study utilizes micro-level project data. The primary source is the World Bank’s PPI database, which catalogs 642 water PPP projects implemented between 1994 and 2021. These projects encompass water treatment plants (potable water and sewerage) and water utilities. Notably, the World Bank’s PPI database does not include the PPP projects undertaken by SOEs. To address this gap, data on additional PPP projects, including those by SOEs, are sourced from China’s national PPP database. Established by the Ministry of Finance of China in 2013, this database records PPP initiatives in infrastructure and public services across China. For data consistency, only water treatment plant and utility projects from the national PPP database are included in this study. By eliminating projects that miss the total investment value or recur in another database, we finally constructed a database covering 2024 water PPP projects from 1994 to 2021 in China (see Figure 2). In addition to primary sources, secondary data are gathered from the E20 Environment Platform website (see Appendix A List 3).

Figure 2.

Flowchart of data processing.

This study conducts a descriptive statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics is used to summarize a set of observations in order to communicate the largest amount of information in the simplest way possible [55]. By employing descriptive statistics, we measure the following: (1) the frequency and percent of the volume of water PPP projects by different types of private capital; (2) the mean, standard deviation, min, and max of project investment by each type of private capital.

For China’s water market, there are five kinds of water companies: (1) water transnational corporations, (2) foreign-specialized operators, (3) SOEs either at the central or local level, (4) privatized local water companies, and (5) domestic operators [33]. Various forms can be identified in both water supply and waste water treatment, including BOT, TOT, part or full sale, and management contract [56]. Compared to the highly decentralized water PPP market, the water governance structure is somewhat centralized to the local government, regardless of the fragmentation or integration model. In the areas of water governance, the fragmentation model states that water affairs-related government functions are served by different municipal government agencies in China. A municipal environmental protection agency is in charge of sewage treatment; water supply is managed by municipal water utilities; the Bureau of Construction is in charge of water-related infrastructure projects [57]. However, many municipal governments have also adopted water integration reform and established a water affairs bureau to take charge of water resource management, water pollution control, and water-related infrastructure projects.

Taking China’s water organization and market structure into account, we divide private capital into four types, including foreign capital, domestic private capital, SOE, and the mixed-capital consortium based on the institutional links between different types of private capital and political authorities. Different types of private capital experience different resource and regulatory constraints based on their institutional links [58]. SOEs enjoy the closest institutional links and share institutional similarities with local governments [59]. Chinese domestic private capital encounters institutional discriminations and is listed as the last to receive financial resources under the political pecking order [60]. Mixed-capital consortiums occupy an intermediary position, blending characteristics of both SOEs and private firms. The institutional links between foreign capital and political authorities are contingent upon the openness and receptiveness of public policies. The type of private capital for each project is justified through the TianYanCha website (see Appendix A List 4).

Table 1 displays the descriptive statistics for water PPP projects in China from 1994 to 2021 across four private sector categories. While the introduction of PPP has been far from prefect, private sector participation has been far more extensive [12]. In total, 2024 water PPP projects were analyzed, with a cumulative total investment of USD 157,297.7 million. The SOE sector not only has the highest share of project total investment but also features the largest average and maximum investment values. In contrast, the foreign capital and domestic private capital sectors contribute smaller portions of total investment, with foreign capital having the lowest mean and range of investment values. Specifically, foreign capital accounts for 9.7% of the total projects, with a total investment of USD 8780.5 million, representing 5.6% of the overall investment. The mean investment in this category is USD 44.8 million, which is significantly lower than that of the SOE sector. Domestic private capital, comprising 30.5% of the total projects, owns 14.2% of the total investment. While its mean investment is lower than that of the foreign capital sector, the minimum and the maximum investment values are higher. SOE has captured a significant share of 48.1% in project volume and 65.8% in project value. The mean investment in this category is notably higher at USD 106.3 million. The mixed-capital consortium sector, which takes 11.8% of the projects, contributes to 1.4% of the total investment. Its mean investment is higher than that of domestic private capital and foreign capital but lower than that of SOE.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

The validity and reliability of our findings are ensured through three distinct methods. Firstly, we seek convergence within quantitative and qualitative data concerning foreign participation in China’s water PPP projects. This approach of triangulation allowed us to validate our results by corroborating findings from multiple sources and methodologies. Secondly, we utilized a typological approach to categorize foreign participation in China’s water PPP development. This categorization was based on financing and operational aspects, dividing foreign involvement into four distinct types. This systematic classification facilitated a clearer understanding of the different roles and contributions of foreign participation in these projects. Thirdly, we ensured the reliability of our findings through replication processes. New cases were added and analyzed within our study framework, and these additional cases confirmed the consistency and robustness of our initial findings.

4. Results

4.1. Private Sector Participation in China’s Water PPP Development

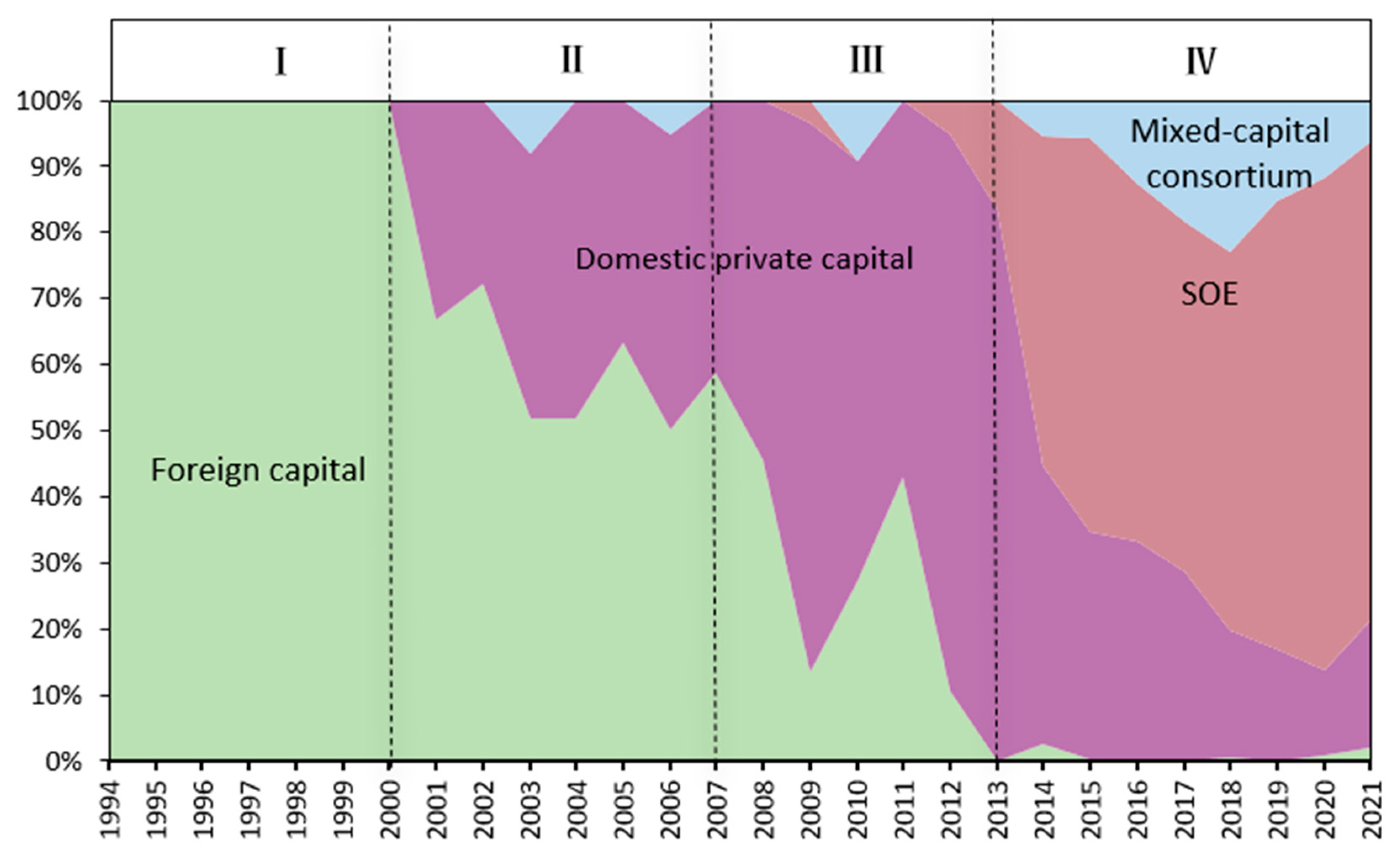

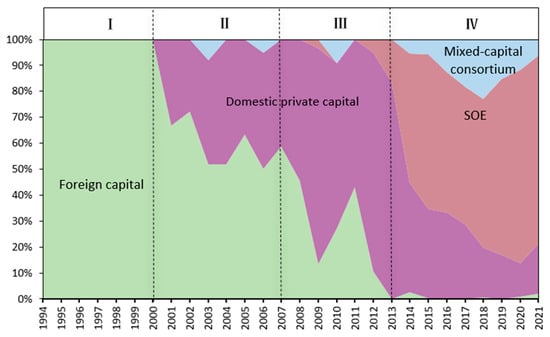

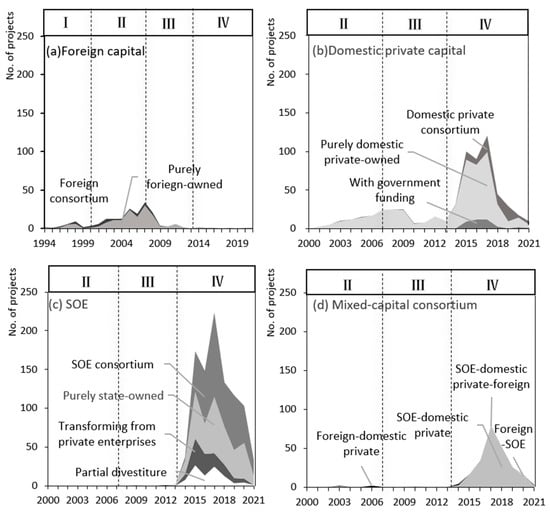

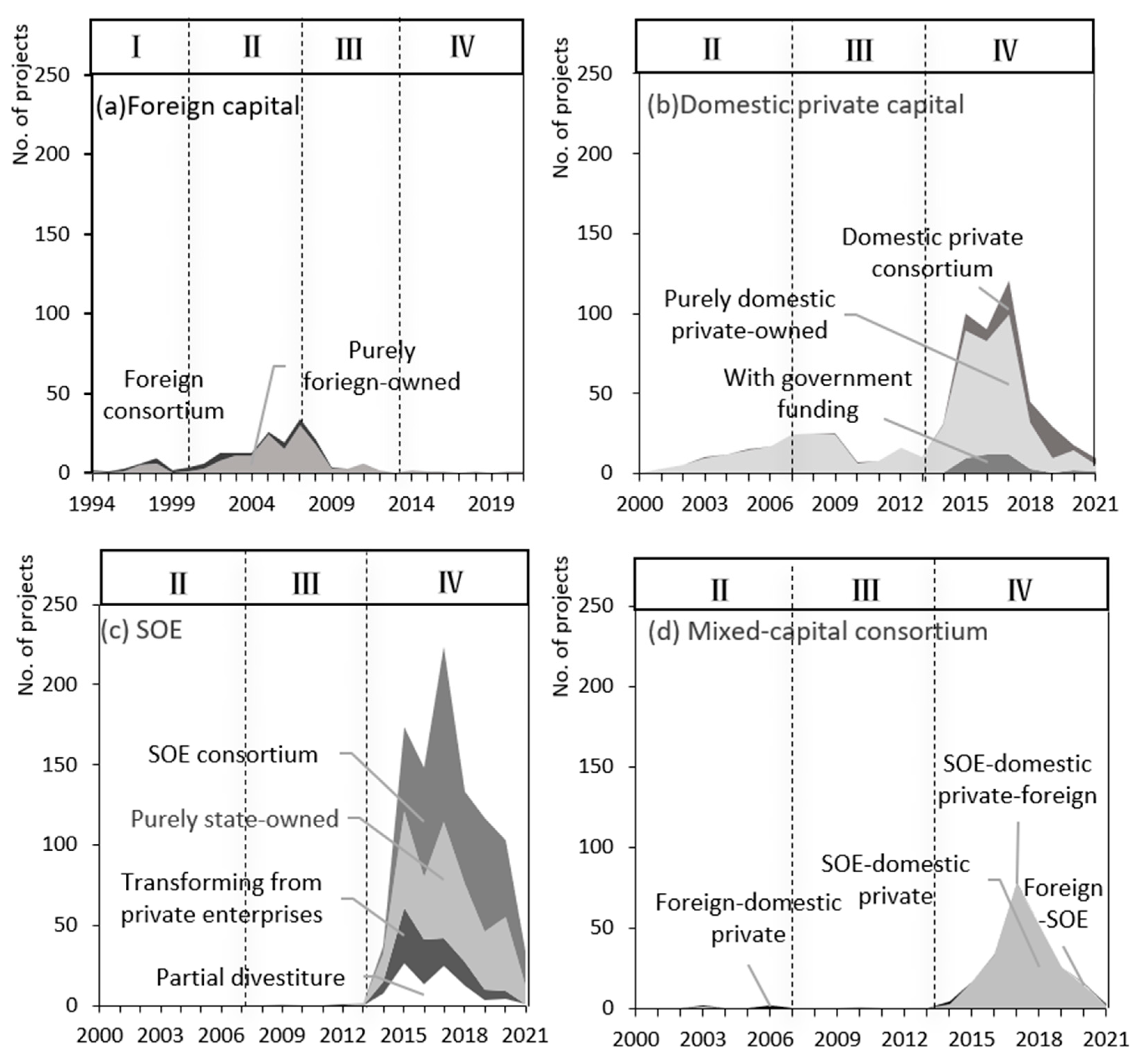

We analyze the annual distribution of four key capitals contributing to the total volume of water PPP projects in China from 1994 to 2021. This examination allows us to trace the involvement of the private sector throughout the evolution of China’s water PPP development, forming four distinct periods (see Figure 3, Table 2, and Figure A1). Within each period, we discuss the water PPP projects and private sector participation.

Figure 3.

Yearly shares of four capitals by volume of PPP projects from 1994 to 2021.

Table 2.

Private capital and water segment types in four periods covered in this paper.

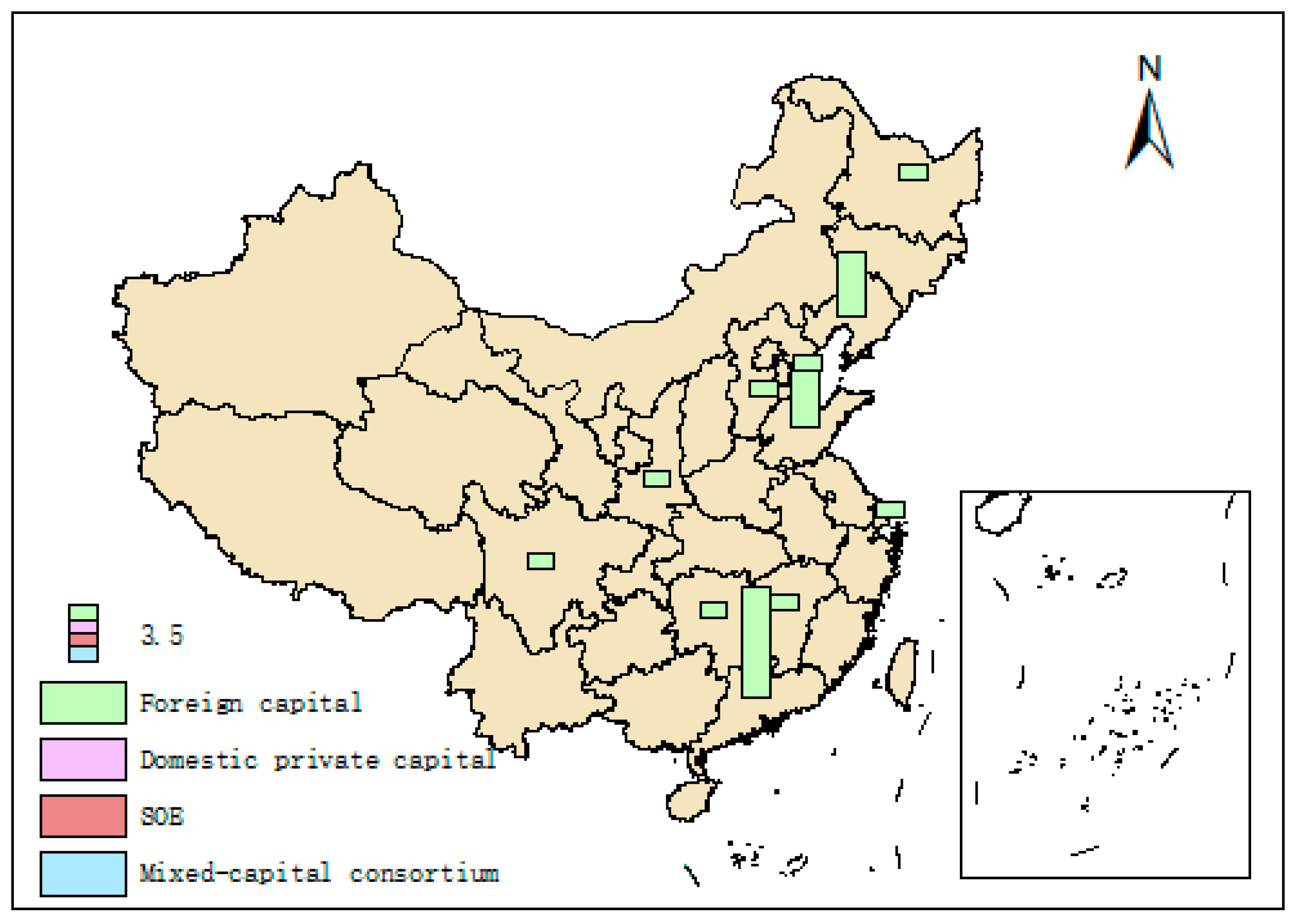

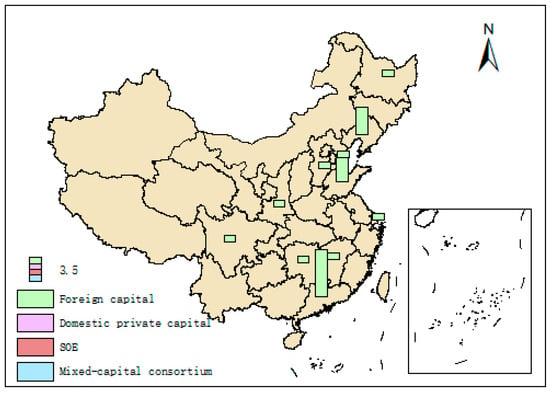

4.1.1. Foreign Monopoly: 1994–2000

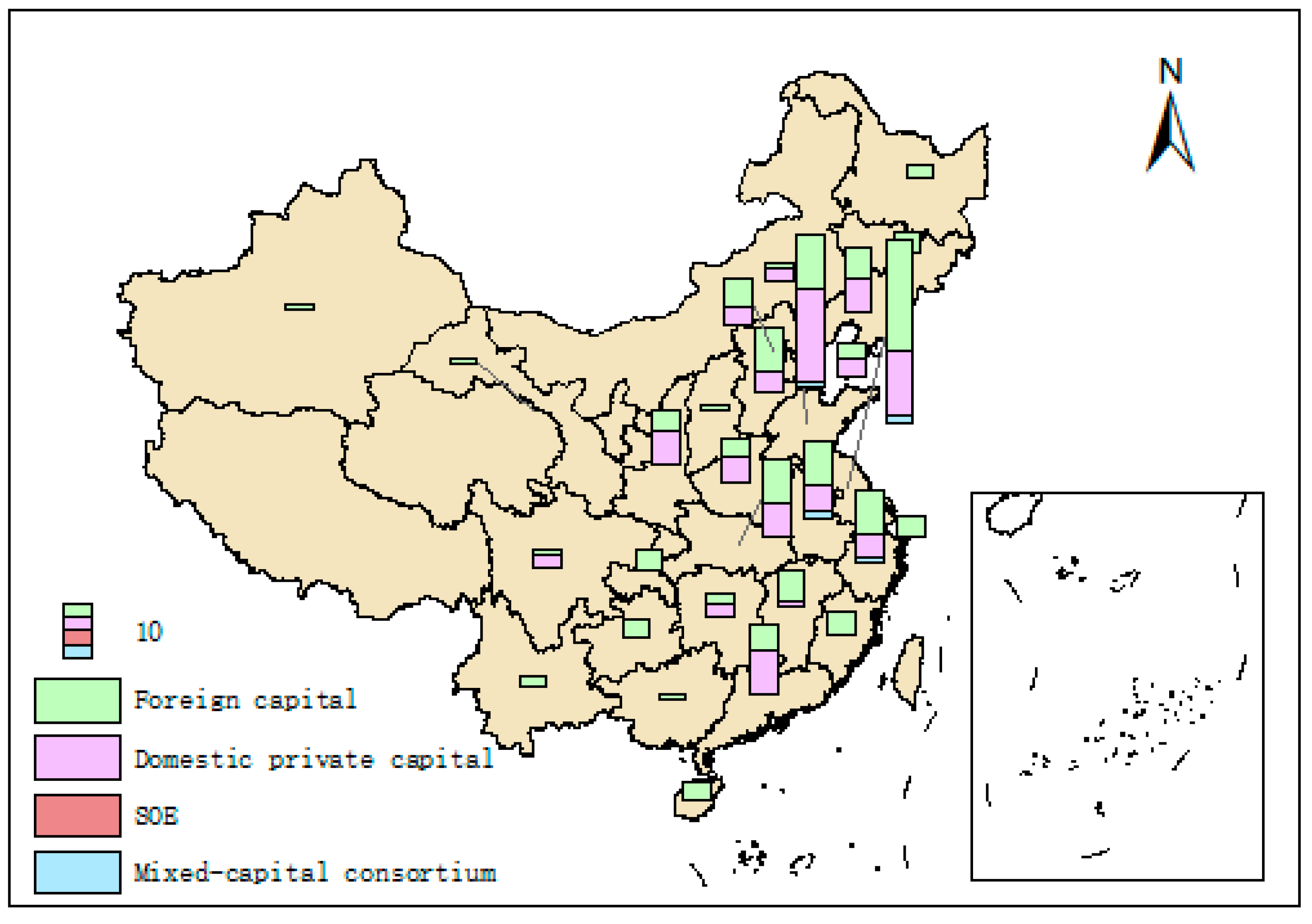

The typical feature of private sector participation during this period is that foreign capital took all the water PPP projects (see Figure 4). Most projects were concentrated in eastern coastal provinces, such as Guangdong and Jiangsu, reflecting their advanced economic development and openness to foreign investment. There were 27 projects, and the total investment added up to USD 955.1 million. Most projects were potable water treatment plants, with only three sewerage treatment plants and one water utility plant without sewerage. BOT accounted for 40.74%. Among the sub-types of foreign capital, 52% of the projects were untaken by purely foreign-owned enterprises, and the rest were taken by foreign consortiums. Cooperative joint venture (CJV) emerged as the predominant investment model, wherein foreign and local partners contributed capital either in cash or assets as stipulated in the contractual agreements [38]. Notably, under CJV arrangements, three projects were entirely owned by foreign entities, namely the Da Chang water treatment plant, Chengdu No. 6 water plant B, and Hexian water treatment plant.

Figure 4.

Distribution of water PPP projects from 1994 to 2000.

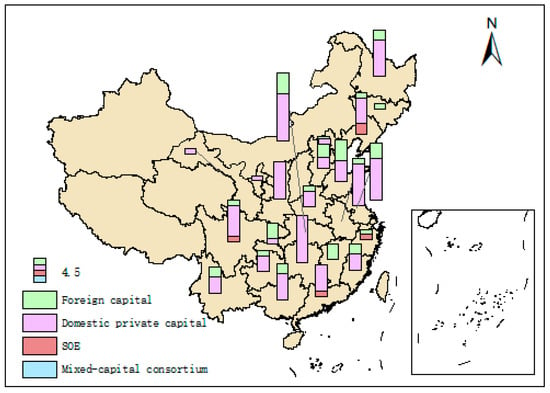

4.1.2. Gradual Domestication: 2001–2007

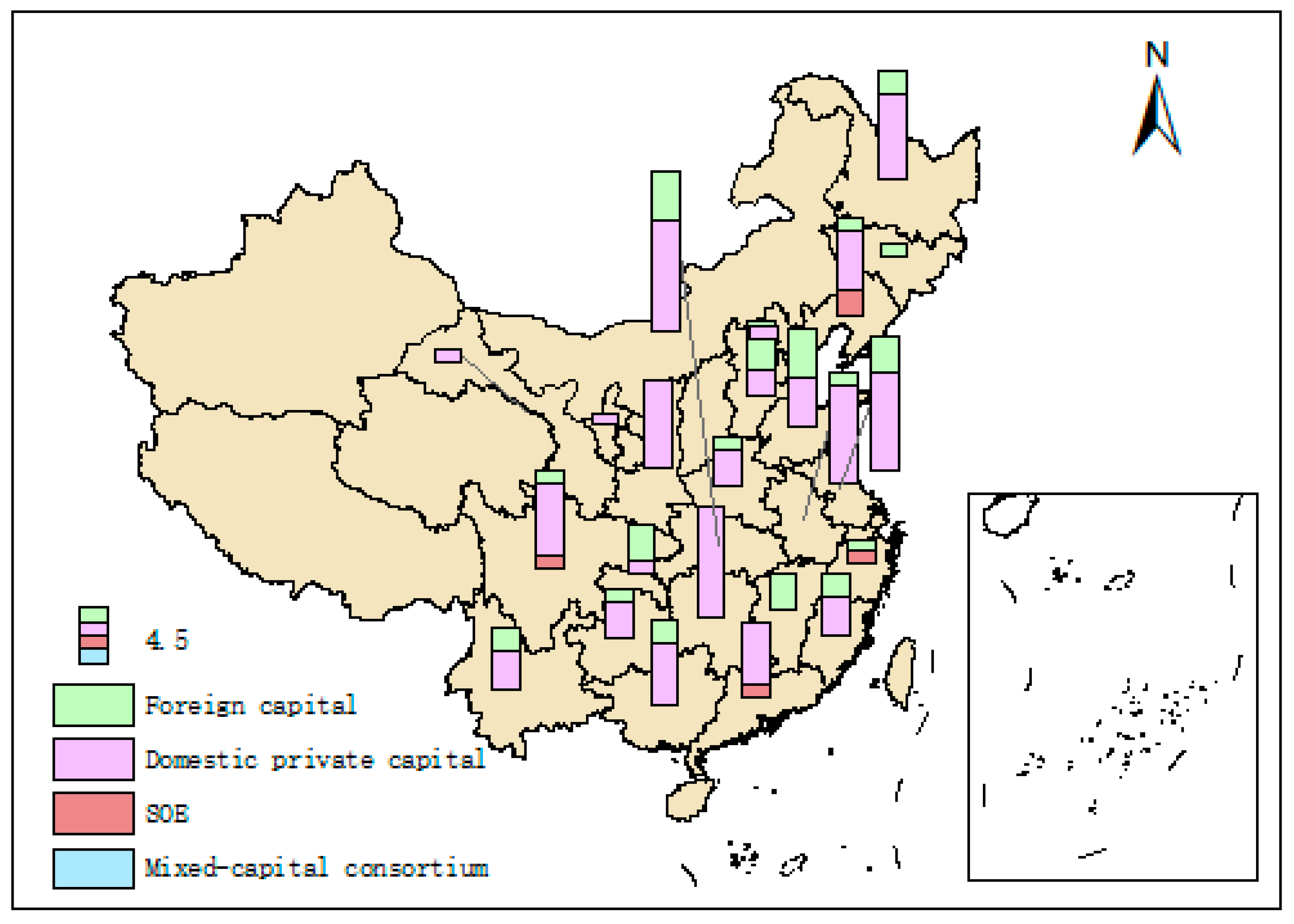

The typical feature of private sector participation in this period is that Chinese water PPP market was gradually domesticated (see Figure 5). There was a significant increase in the number of water PPP projects compared to earlier years. A majority of the projects were concentrated in economically advanced eastern and southeastern regions, including provinces like Guangdong, Jiangsu, and Shandong. These areas are hubs of economic activity and have strong infrastructure demands. There was also a gradual diffusion of projects toward central and western regions. This period witnessed a significant increase to 214 projects, collectively attracting USD 5938.9 million in investments, nearly six times the amount from the previous stage. With the opening of the sewerage treatment market for private participation in 2002, sewerage treatment plants accounted for nearly 62% of the projects, marking a substantial shift from potable water plants, which decreased to 22%. BOT was adopted in over 60% of the projects during this period. The model of the wholly foreign-owned enterprise (WFOE) became dominant. Additionally, joint stock companies (JSCs), established by the Chinese local government for listing on stock markets, started to appear in this period [38].

Figure 5.

Distribution of water PPP projects from 2001 to 2007.

This period witnessed the rise of Chinese domestic capital. Initially, in 2001, Chinese domestic private capital was involved in only three projects. However, over the years, its involvement grew significantly, taking up around 40% of the yearly projects on average. The ratio reached its highest at 48% in 2004. But foreign capital continued to play a dominant role, accounting for nearly 58% of the projects and contributing 81% of the total investment during this period.

4.1.3. Accelerated Domestication: 2008–2013

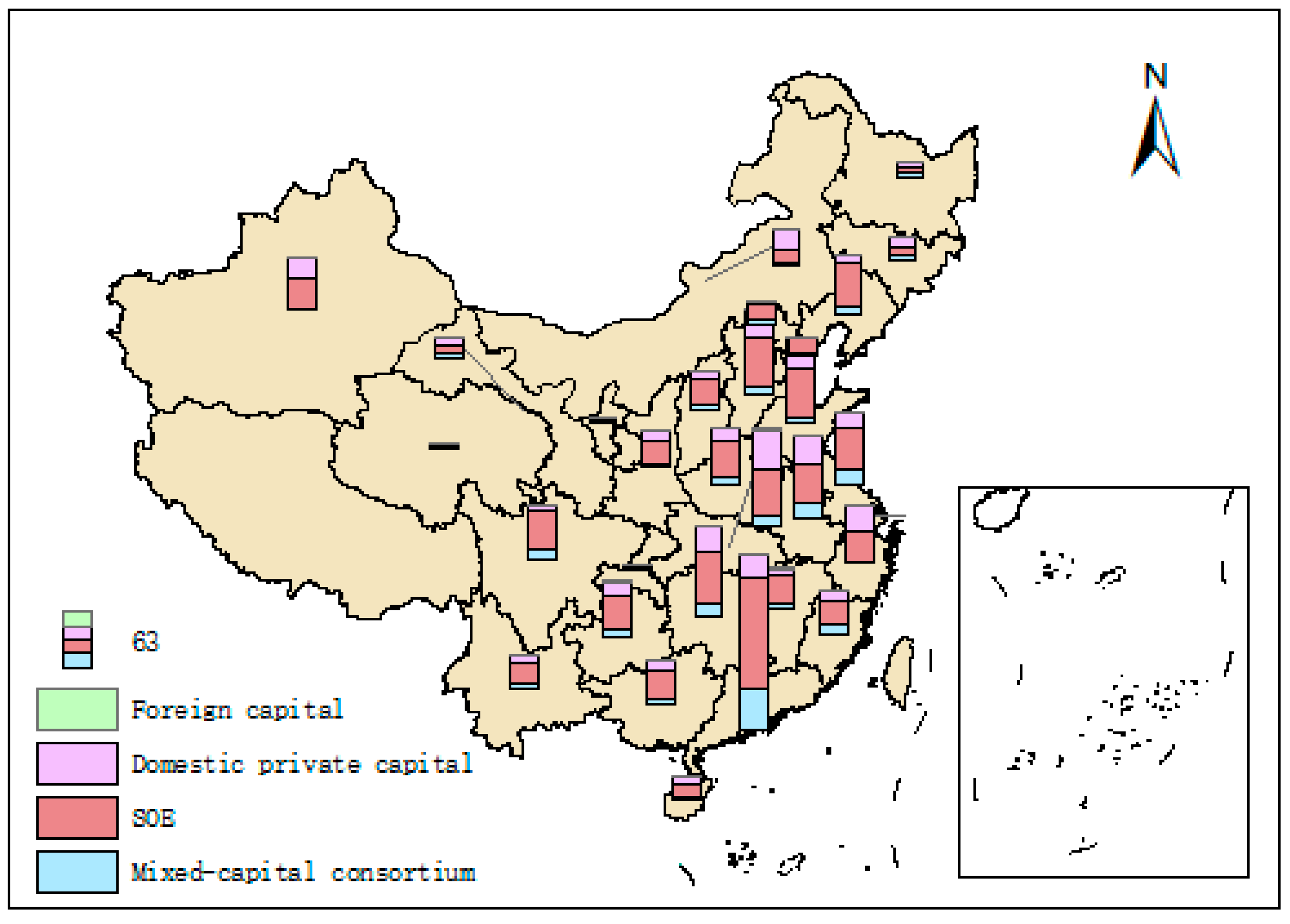

The typical feature of private sector participation in this period is that Chinese domestic private capital took control of the water PPP market, alongside the emergence of SOEs (see Figure 6). Water PPP projects during this period was more evenly distributed across China. However, the number of water PPP projects experienced a significant decline of 36%, accompanied by a 55% decrease in total investment. The dominant type of PPP was still BOT. And nearly 91% of the projects were sewerage treatment plants.

Figure 6.

Distribution of water PPP projects from 2008 to 2013.

The domestication process accelerated during this period. SOEs appeared in the water PPP market since 2009 and undertook a few water plant PPP projects. Chinese domestic private capital significantly increased its participation, accounting for nearly 70% of all projects. Conversely, foreign participation experienced a noticeable decline during this period. After a sharp drop from 46% in 2008 to 11% in 2009, the market share held by foreign capital temporarily rebounded to 27% in 2010 and 43% in 2011. However, by 2013, foreign participation had declined to 0%.

4.1.4. SOE Domination: 2014–2021

The typical feature of private sector participation in this period is that SOEs dominated the water PPP market, accompanied by a notable absence of foreign capital (see Figure 7). This era marked a significant PPP boom in China’s water sector, with a total of 1651 projects, three times the number observed in the previous twenty years, and a staggering twelve-fold increase in total investment. The geographic distribution of projects became more balanced, with a significant growth in central and western provinces such as Sichuan, Shaanxi, and Yunnan. This reflects the growing governmental efforts to improve infrastructure in less-developed regions. BOT was employed in 74% of the projects. For segments, water utility with sewerage attracted 72% of total investment, sewerage treatment plants followed with nearly 18%, and portable water treatment plants only accounted for 1%.

Figure 7.

Distribution of water PPP projects from 2014 to 2021.

The PPP market for this period was dominated by revitalized (and often corporatized) SOEs that combine their utility business with financial services businesses [40]. SOEs controlled 59% of the water projects and contributed to 74% of the total investment. Moreover, 2.8% of them undertook nearly 30% of water PPP taken by SOEs. SOE consortium participation became increasingly prominent from 2016 to 2018, with average investment levels reaching up to USD 149.56 million. Domestic private capital lost its leading role in the previous period, maintaining a stable market share of approximately 26% annually. Mixed-capital consortiums became active and participated in two hundred thirty-one projects, compared to only five from 1994 to 2014. Notably, 97% of the 231 projects were taken by SOE–domestic private consortiums, with an average investment level of USD 96 million. In contrast, foreign capital played a minor role, participating in only 14 projects that were concentrated in the sewerage treatment subfield and located in underdeveloped provinces or county-level areas. Half of these projects involved co-investment with Chinese domestic capital, with foreign capital holding relatively small shares ranging from 1% to 29%.

4.2. Foreign Participation and Its Decline in China’s Water PPP Development

From the above analysis, we see an obvious foreign capital involvement, from establishing a monopoly or domination before 2007 to losing its leading position and finally the absence of a “PPP boom” since 2014. This section introduces a framework based on resource dependence theory to display typical facts of foreign participation in China’s water PPP waves. Resource dependence theory, widely utilized in explaining mergers, joint ventures, boards of directors, political action, and international business [61,62], posits that while the focal organization depends on other parties in its environment for critical resources, it would engage in different interorganizational arrangements, including alliances, in-sourcing, and joint-ventures, to decrease dependence asymmetry and foster interdependence [63]. Different levels of resource dependencies are an antecedent to different interorganizational arrangements [64]. Joint ventures are formed to facilitate reliable and durable access to the resources of partner organizations; insourcing avoids the integration problems, and alliances can usually be terminated without legal consequences for focal organizations [64]. Three key factors influence the dependence of a focal organization on other organizations: the criticality of the resource for organizational survival, the internal availability of the resource, and the existence of viable alternatives [63].

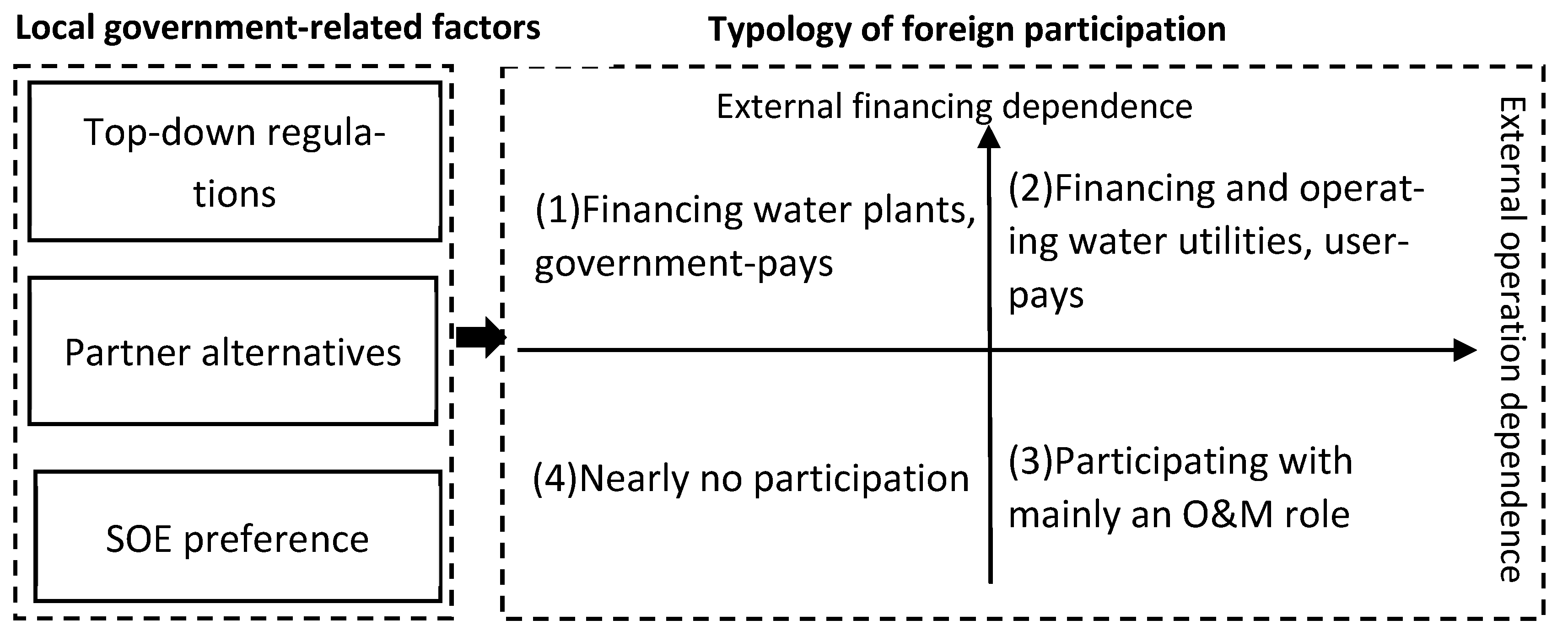

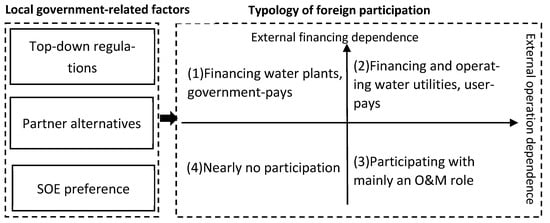

Based on research on resource dependence theory and taking the local government as the focal organization, we establish a typology to categorize foreign participation in China’s water PPP development, highlighting three key local government-related factors that influence foreign involvement (see Figure 8). The local government is driven by efficiency incentives and control considerations in collaboration with foreign capital. On the one hand, for efficiency incentives, the resource-trapped local government relies on foreign capital for external financing and operation resources [65]. The local government, facing fiscal constraints and limited debt financing options, often turns to foreign capital for financial support [66,67]. And the local municipal water SOE, accused of not capable of maintaining the smooth running and the assured continuation of its operation [68], depends on foreign capital for external operation expertise and experience. On the other hand, under control needs, including the coordination of political interests, the control of infrastructure property rights, the equalization of service supply, and the protection of public interests, local governments turn to employ strategies to mitigate dependence asymmetry and regain autonomy and control.

Figure 8.

Analytic framework. Note: SOE = state-owned enterprise; O&M = operation and maintenance.

There are three factors influencing local government balance between fulling efficiency incentives and taking control: (1) top-down regulations, including encouragement and restrictions from the central government on collaboration between the local government and foreign capital; (2) partner alternatives, equaling to the availability of other private partners for the local government, besides foreign capital; and (3) SOE preference. The Chinese local government has a preference for cooperating with SOEs, resulting from the Chinese political pecking order in financial resource allocation and considerations of transaction cost saving [58,60].

4.2.1. Financing Water Plants, Government-Pays

The Chinese local government adopts an in-sourcing arrangement to establish mutual dependence under external financing dependence on foreign capital. On the one hand, the local government depends on foreign capital for financing resources. A whole or partial foreign-owned special purpose vehicle (SPV) is set up, taking the responsibility of project financing, designing, construction, operation, and maintenance under the BOT or TOT model for a certain period. Once the concession period came to its end, the water plant would be transferred to the government free of charge. On the other hand, foreign capital depends on the local government to recover their investment and generate profits through government financing, including selling bulk water to state-owned water supply companies and receiving sewage treatment service fees from fiscal funds.

This was the major type of foreign participation in China’s water PPP market. It was initially employed in China’s water PPP wave from 1994 to 2000. Firstly, Chinese local governments showed heavy dependence on external financing resources in the 1990s. China’s tax assignment reform in 1994 resulted in the Chinese local government retaining only 44% of its fiscal revenues while undertaking 90% of spending responsibilities [69]. And local governments were not allowed to issue bonds according to the 1984 Budget Law. Secondly, the Chinese local government did not have alternatives besides foreign capital. For this period, Chinese domestic capital was relatively underdeveloped and did not actively participate in the water PPP market. In 1995, the Chinese central government initiated five pilot BOT projects, spanning sectors such as energy, water, and transportation. Under central government encouragement, Chinese local governments competed to collaborate with foreign investors under the BOT model, thereby promoting foreign participation in infrastructure development.

However, all 27 projects undertaken by foreign capital through the government-funded arrangement were characterized by fixed return guarantees. Financing water plants under the government-funded arrangement was more feasible and controllable for local governments who had little prior PPP experience. But for foreign capital who were not allowed to step into the water distribution network and could only sell water to government departments, they refused to participate unless they were promised a fixed water purchase price and amount.

The growing need to control and the decreasing dependence on foreign capital by the local government lead to the fall of foreign participation in financing water plants. Firstly, local governments faced enduring internal fiscal resource losses and perceived exploitation from foreign participation due to fixed return guarantees. This contractual obligation placed significant fiscal burdens on Chinese local governments. For instance, in the Chengdu No. 6 Water Plant B project, two publicly operated water plants were forced to shut down because local water consumption fell well below the agreed upon fixed amount, leading to financial strain on the local state-owned water supply company. The project underwent an 18-year debatable concession period [70]. Secondly, national policies became strict on partnership between local governments and foreign capital on financing water plants. The Chinese central government treated projects with guaranteed fixed returns as illegal and started a top-down cleaning-up movement, resulting in many water PPP projects being terminated or canceled [33]. This regulatory shift discouraged ongoing partnerships between foreign capital and local governments, resulting in minimal development of new water plant projects. Thirdly, Chinese domestic capital begun to substitute foreign capital in filling local government financing gap since the second phase.

Consequently, the partnership between local governments and foreign capital in financing water plants declined notably over subsequent periods. China opened its urban sewerage treatment plant market in 2002. A total of 60% of sewerage treatment plant projects were taken by domestic capital, and foreign capital only took 40% in the second period. In general, for financing water plants, foreign capital fell to 51% in the second period, 25% in the third period, and 0.3% in the fourth period.

4.2.2. Financing and Operating Water Utilities, User-Pays

The local SOE affiliated with the local government forms a joint venture with foreign capital under local government external financing dependence and external operation dependence. An increase in dependence on foreign capital leads to the local government adopting a joint venture to form mutual dependence. The local government at first packs water plants and utility network assets into an existing or newly built water utility facility and then converts it into a shareholding company through shareholding reform. Then, the local government sets the share transfer ratio, usually below 50%, and offers shares to private investors through a public bidding process [71]. Part of the funding brought in by foreign capital would stay in the joint venture. Foreign capital takes on the water supply service to end-users as well as water production or the treatment service, thereby generating revenues by charging fees via user-pays.

This type was predominantly utilized during the Chinese second water wave from 2001 to 2007. Firstly, local governments showed heavy dependence on external financing and operation resources. The promotion of urbanization led to increased demand of water infrastructure in and outside urbanized areas. But local governments were still not allowed to borrow. Meanwhile, the 16th National Congress of the CPC recognized the mixed-ownership reform of SOEs, placing more emphasis on company management and operation. Secondly, Chinese local governments did not have alternatives to finance and operate large and medium water PPP projects besides foreign capital. Domestic private capital, constrained by limited financing resources and operational expertise, primarily participated in smaller scale projects during this period. Thirdly, the Chinese central government turned to promoting domestic private investment in 2001 as well as allowing foreign investment to participate in distribution networks which were previously not open to them.

Foreign capital in financing and operating water utilities in China exhibited two distinctive characteristics. Firstly, foreign capital used to pay an extraordinarily high premium to acquire the transferred shares in the second period [71], ranging from 5% to 280% above the asset value (see Table 3). Secondly, the failure to recover the investment by raising water tariffs led to foreign capital engaging in water service cost reduction rather than quality improvement. Under the principle of “one water price in one city”, the applications for raising water tariffs by foreign capital were always rejected by local governments. Chinese politicians, particularly local government leaders, are reluctant to pay high ‘political prices’ by reforming water tariffs, which might result in their loss of power [72].

Table 3.

Cases of excessively high premiums in water utility share transfer.

The growing need to control and the decreasing dependence on foreign capital by the local government lead to the fall of foreign participation in financing and operating water utilities. Firstly, local government suffered the loss of social trust and internal fiscal resources due to their collaboration with foreign capital. Secondly, the Chinese central government tightened securitization on cases of excessively high premiums in water utility share transfer. Following a significant water pollution incident and subsequent social criticism on foreign involvement in water areas, the Chinese central government initiated multiple rounds of stringent oversight on cases of excessively high premiums in water utility share transfer. Subsequent partnerships between the Chinese public sector and foreign capital under this scenario was notably restrained. Thirdly, Chinese domestic capital replaced foreign capital in financing and operating water utilities. Chinese domestic private companies stepped into the water utility market in the third period, and SOEs appeared in the fourth period.

Consequently, the cooperation between local governments and foreign capital on financing and operating water utilities declined significantly. Of the nearly 1000 water utility PPP projects during the fourth period, 64% were occupied by SOEs, 18% were taken by domestic private enterprises, and the remaining, approximately 18%, were predominantly handled by SOE–domestic private consortiums. In contrast, foreign capital was involved in only five projects.

4.2.3. Participating with Mainly an O&M Role

The local SOE affiliated with big municipal governments adopts an alliance arrangement to form mutual dependence under external operation dependence on foreign capital. These alliances typically take the form of joint ventures or management contracts with foreign partners. Simultaneously, the local SOE retains control over the rights and investment decisions, maintaining the flexibility to withdraw from the alliance if necessary.

This approach became more prevalent during the third stage, particularly in large cities, for several reasons. Firstly, the dependence on external operation resources by the local SOE in large cities escalated. On the one hand, the local government engaged in land financing and issuing local government-related bonds, showing less demand for external financing resources [74]. On the other hand, the economically sound local governments started to engage in nurturing their affiliated SOEs into regionally and even nationally leading water operators [38]. Secondly, local SOEs had no alternatives besides foreign capital. Chinese domestic capital encountered institutional discrimination and could not afford the cost of acquiring the transferred state-owned shares.

Large cities like Beijing, Shenzhen, and Chongqing had succeeded in nurturing nationally leading water SOEs by cooperating with foreign capital. With foreign capital taking on operation and maintenance (O&M) responsibilities, the Beijing Capital transformed from a local capital-intensive company to a nationally leading water company. The Shenzhen Water Group grew from a traditional local water SOE to a national leader in water technology and operation, and the Chongqing Water Group was listed in 2010 and expanded its business to broader environmental areas.

However, the growing need to control and the decreasing dependence on foreign capital by the local government led to the fall of foreign participation in forming an alliance with local municipal water SOEs. Firstly, the local government suffered losses when allying with foreign capital. Foreign capital quickly lost its value after local SOEs became equipped with operation and maintenance experience and know-how [40]. Those SOEs began to emerge as principal contractors in water projects and competed with foreign capital for cross-regional water PPP projects. However, under the restrictions of the Bidding Law whereby parent and subsidiary companies cannot bid on the same project at the same time, the business expansion process of local SOEs was therefore not smooth, owing to the parent–subsidiary relationship between the foreign partner and the investment company. Secondly, domestic private capital emerged as the preferred alliance partner for local SOEs, often assuming subcontractor roles.

Consequently, the partnership between the local government and foreign capital in forming alliances decreased, with the local government increasingly turning to domestic capital. A total of 97% of projects undertaken by mixed-ownership consortiums were led by SOE–domestic private consortiums. Within these consortiums, SOEs assumed primary responsibility for bidding and financing, leveraging their established positions and resources, while domestic private companies typically acted as subcontractors, focusing on the operational aspects.

4.2.4. Nearly No Participation

In China’s fourth water PPP wave since 2013, Chinese local governments still demonstrated a significant reliance on external financing and operational resources. On the one hand, the active fiscal policies during China’s third water PPP wave led to unrestrained local-level investments, exacerbating local government debt issues. Moreover, the cash-strapped Chinese local government was prohibited from borrowing through LGFVs since 2014. On the other hand, China’s water policies have transitioned from engineering-focused approaches to management- and governance-centered strategies in recent decades [75]. This shift emphasized the need for improvement in local SOE operations, aligning with national objectives for enhanced efficiency and sustainability in the water sector.

However, the limited dependence on foreign capital for external financing and operation resources led to nearly no foreign participation, particularly evident in China’s latest water PPP wave. On the one hand, Chinese local governments turned to rely on SOE partners for external resources during this period. Chinese local governments welcome SOEs because they have adequate financial and physical resources to undertake the project [76] and are capable of obtaining larger-scale and lower-cost financing that was backed by government credit. And the institutional similarities between SOEs and local governments reduce transaction costs associated with cooperation [59,76]. Specifically, the SOE-led consortiums, combing financing and operation resources together, provided local governments with viable alternatives to foreign capital. These consortiums typically fall into three main types. The first type comprises SOEs involved in financing, construction, and operation. The second type involves partnerships between nonlocal SOEs and local private companies where the PPP project is situated. The third type consists of collaborations between companies within the same state-owned business group. On the other hand, SOEs are more task-driven in participating in PPP projects, which allows them to accept lower returns compared to private enterprises [54]. This gives the local government more room to control.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

5.1. Conclusions

This research discussed the involvement of foreign capital and its decline in China’s water PPP development in the past thirty years. We detect four periods of China’s water PPP development from 1994 to 2001 and find that foreign participation evolves from being a monopoly to being replaced by Chinese domestic capital. Foreign capital fills the local government financing gap and the local SOE operation gap. However, collaboration with foreign capital brings extra risks to Chinese local governments. The growth of domestic capital gives the Chinese local government more alternatives. As a result, the growing need of the local government to control, together with its decreasing dependence on foreign capital for financing and operation resources, led to the fall of foreign participation.

Our research has three contributions. Firstly, we provide a more systematic analysis of private sector participation in the water sector by taking SOEs and mixed-ownership consortiums into consideration. Taking institutional links into consideration, we categorize private capital into foreign capital, domestic private capital, and mixed-ownership consortiums. This category aids in revealing collaborations among various private investors. While researchers observed that Chinese SOEs bridged capability gaps by turning to private partners [77], our analysis indicates that collaboration tends to be more enduring and robust through the establishment of investment consortiums or joint ventures. Secondly, we employ resource dependence theory and consider the efficiency incentives and control needs of the local government to categorize foreign participation in China’s water PPP development. There are four categories, which are financing water plants under government financing, financing and operating water utilities under user financing, participating with mainly an O&M role, and nearly no participation. This category can contribute to PPP employment in the water area in other developing countries. Thirdly, we ascribe foreign participation and its decline in China’s water PPP development to that of the Chinese local government strategically balancing efficiency incentives and control needs. This complements existing explanations that state that the massive retreat of foreign investment in China’s water PPP market results from the risk aversion choice of foreign capital and the crowd-out effect by Chinese domestic investors.

We have several suggestions for foreign participation in PPP projects. Firstly, great attention must be paid to the first-time cooperation with local governments. The success of the first-time partnership can foster familiarity and trust between the public sector and foreign capital, thereby reducing the transaction costs associated with public sector control needs and leading to more collaborations. Typically, foreign capital should not take advantage of the resource dependence of the public sector and the lack of experience of government officials [78]. Secondly, it is necessary to form joint ventures with local SOEs who are affiliated with the local government. The joint venture bundles the foreign capital and the local SOE together, allowing the foreign capital to benefit from the local government’s SOE preference. Encouraged by SOEs, many of the implicit policy discriminations and government default risks that typically challenge foreign capital can be mitigated. Thirdly, foreign capital should engage in localization processes when undertaking overseas PPP projects. The localization of foreign involvement and the attached relationship-specific investment send credible commitments to local governments, thereby attracting more positive feedbacks from the public sector. Foreign capital should not only align with local market conditions and regulatory frameworks but also facilitate knowledge transfer and build long-term trust with its local partners.

5.2. Discussion

The price of efficiency gains brought by foreign capital is a reduction in local government’s ability to manage the service delivery process, the quality of the service, and the distributional objectives of water service [79]. A decision by the local government to adopt PPP projects always signals ‘bad news’ that the local government is running low on revenues and its debt level is so high such that it cannot borrow any more [80]. To avoid losses, foreign capital requires that local governments must promise guaranteed repurchase or guaranteed rates of return, otherwise they would not participate in a project. Furthermore, the related arrangements must be clearly displayed in the contract in case of government default risks. But such a requirement would leave local governments and officials in heavy fiscal burden and higher political risks and credit risks from upper governments, society, and market, just like what happened in China’s water market in the 1990s and 2000s.

Compared to foreign capital, the local government can better balance efficiency gains and control needs under a partnership with Chinese domestic capital. Although Chinese SOEs and local private enterprises may also request government guarantees, they can accept such agreements outside the formal contract, thereby providing local governments with greater flexibility to balance efficiency gains and control needs. For SOEs, they are not afraid of government default risks because they hold relative bargaining power towards the local government [76]. SOEs and local governments share institutional similarities with local governments as they both belong to the public sector, public shareholders, and personal networks, costing them less transaction costs [60]. There is also a tendency that Chinese-led water SOEs are forming closer institutional links with local governments via signing strategic cooperation agreements. For local private enterprises, they also hold relative bargaining power towards the local government due to their essential importance for local economic development, tax contribution, jobs provision, and social stability. Furthermore, the familiarity with the local government through repeated interactions, personal connections, and informal links can breed trust [81,82].

The growth of SOEs provides Chinese local governments with an alternative besides foreign capital. Nearly half of the water SOEs have transformed into a quasi-independent market actor through corporatization reform. SOEs also cooperate with domestic private capital through mergers, acquisitions, and investment consortiums. Many Chinese-led private enterprises also adopt mixed-ownership reform and welcome government shareholders through mergers and acquisitions. Therefore, SOEs can rely on domestic private enterprises to undertake operational tasks.

However, SOE domination in China’s PPP market leads to huge contingent liability problems at the local level [83]. To deal with this problem, very recently in 2023, the Chinese central government put forward the “PPP New Mechanism”, granting private capital with participation privilege. It is a friendly institutional arrangement for foreign and domestic private capital. Beyond traditional projects, where local governments still favor SOEs, both foreign and domestic private capital can increasingly focus on more specialized and operationally advanced water-related PPP projects.

The climate change-related water PPP project is one such example. In the coming years, water PPP project finance and infrastructure development are set to become a massive area of investment and attention across the globe, driven by climate change and a basic need for infrastructure development, restoration, and renovation [41]. Climate change threatens water resource management and development, increases the risk of droughts and floods, and affects the availability and quality of water and sanitation services in hydropower plants around the world [14,84], thereby calling for more climate change-resilient water infrastructure. On the other hand, climate adaption and mitigation also present an opportunity to leverage climate finance mechanisms to provide additional funding to water and wastewater management [84]. This is typical necessary for Chinese domestic private capital, which faces financial constraints and ownership discrimination by the banking sector [85].

The findings presented in this paper, derived from China’s water PPP projects, are subject to three significant context-related boundaries. Firstly, within the politico–administrative regime context, the conclusions are particularly relevant to highly centralized states and governments with authoritative traditions. Secondly, in the project context, the findings are most applicable to capital-intensive and regulated infrastructure sectors such as water and toll roads. Thirdly, for the subtype context, this paper draws conclusions from the analysis of water treatment and utility projects, not taking water-related projects in desalination and environmental remediation areas into account. Compared to water treatment and utility projects, desalination and environment remediation projects are more technical and not directly beneficial towards the public, leading to local governments being more efficiency-oriented in such projects.

For future research, the framework and research approach utilized in this study hold promise for conducting country-level comparative analyses across various infrastructure developments, not just limited to the water sector. Comparative case studies and quantitative analyses could further elucidate the factors contributing to the success of Sino-foreign cooperation in water PPP projects. Such studies would enhance our understanding of how different contextual factors influence the effectiveness and outcomes of PPP adoption in diverse national and sectoral settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.L. and Z.J.Z.; methodology, D.L. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, D.L. and Z.Z.; investigation, D.L. and Z.J.Z.; resources, D.L.; data curation, Z.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, D.L.; writing—review and editing, Z.J.Z.; visualization, Z.Z.; supervision, Z.J.Z.; project administration, D.L.; funding acquisition, D.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 71904052.

Data Availability Statement

Data used in the study were sourced from the following publicly accessible repositories: World Bank PPI database and China’s national PPP database.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

- The World Bank PPI database records global PPP projects at https://ppi.worldbank.org/. Our latest search was on 25 April 2024;

- Social capital refers to enterprises duly organized, validly existing, and in good standing as a legal person under the law of the People’s Republic of China, consisting of domestic private capital, SOEs, and foreign enterprises. However, SOEs controlled by native local governments are not allowed to act as the social capital to participate in PPP projects launched by the native local government [86]. In other words, a SOE, not affiliated with the native local government, is allowed to act on the private side and participate in PPP projects launched by the native local government;

- The E20 Environment platform (https://www.h2o-china.com/) is operated by the E20 Institute of Environment Industry, a specialized think tank focused on China’s environmental development. Our latest search was on 10 January 2025;

- The TianYanCha website (https://www.tianyancha.com) is a commercial database containing rich information about Chinese companies. Our latest search was on 8 January 2025.

Figure A1.

Sub-types of four capitals by volume of PPP projects from 1994 to 2021.

Figure A1.

Sub-types of four capitals by volume of PPP projects from 1994 to 2021.

References

- Grimsey, D.; Lewis, M.K. Accounting for public private partnerships. In Accounting Forum; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2002; Volume 26, pp. 245–270. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. 5 Trends in Public-Private Partnerships in Water Supply and Sanitation (October 2024). Available online: https://ppp.worldbank.org/public-private-partnership/5-trends-public-private-partnerships-water-supply-and-sanitation (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Idelovitch, E.; Ringskog, K. Private Sector Participation in Water Supply and Sanitation in Latin America; World Bank Publications: Washinton, DC, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul-Aziz, A.R. Unraveling of BOT scheme: Malaysia’s Indah water konsortium. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2001, 127, 457–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.P.; Lam, P.T.; Wen, Y.; Ameyaw, E.E.; Wang, S.; Ke, Y. Cross-sectional analysis of critical risk factors for PPP water projects in China. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2015, 21, 04014031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurniawan, F.; Hartono, J.; Nugraha, X.; Putri, A.A. Analysis On The Termination Of Foreign Public-Private Partnership By The Government. IIUMLJ 2022, 30, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Z.; Ma, H.; Lv, K.; Shi, J.J. Liability of Foreignness in Public-Private Partnership Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2023, 149, 04023085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, W.; Xu, F.; Marques, R.C. A bibliometric and meta-analysis of studies on public–private partnership in China. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2021, 39, 773–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asian Development Bank. A Governance Approach to Urban Water Public-Private Partnerships: Case Studies and Lessons from Asia and the Pacific; ADB: Manila, Philippines, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, N.; House, S.; Wu, A.M.; Wu, X. Public–private partnerships in the water sector in China: A comparative analysis. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2020, 36, 631–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Foreign Investment and Public-Private Partnerships in China. Eur. Procurement & Pub. Priv. Partnersh. L. Rev. 2017, 12, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Schuyler House, R.; Peri, R. Public-private partnerships (PPPs) in water and sanitation in India: Lessons from China. Water Policy 2016, 18, 153–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dykes, B.J.; Stevens, C.E.; Lahiri, N. Foreignness in public–private partnerships: The case of project finance investments. J. Int. Bus. Policy 2020, 3, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakbar, T.; Burgan, H.I. Regional power duration curve model for ungauged intermittent river basins. J. Water Clim. Change 2024, 15, 4596–4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogino, K.; Son, J.; Nakayama, M. Effectiveness of hydropower development finance: Evidence from Bhutan and Nepal. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2021, 37, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. Understanding China’s Belt & Road initiative: Motivation, framework and assessment. China Econ. Rev. 2016, 40, 314–321. [Google Scholar]

- RIETI. Introducing METI’s New Policy, “JECOP” (Japan and Emerging Countries CO-Creation Project). 2023. Available online: https://www.rieti.go.jp/en/special/policy-update/109.html (accessed on 2 January 2025).

- Borensztein, E.; De Gregorio, J.; Lee, J.W. How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth? J. Int. Econ. 1998, 45, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.H. How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth in China? Econ. Transit. 2001, 9, 679–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäferhoff, M.; Campe, S.; Kaan, C. Transnational public-private partnerships in international relations: Making sense of concepts, research frameworks, and results. Int. Stud. Rev. 2009, 11, 451–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Chan AP, C.; Chen, C.; Darko, A. Critical risk factors of transnational public–private partnership projects: Literature review. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2018, 24, 04017042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpowicz, I.; Góes, C.; Garcia-Escribano, M. Filling the gap: Infrastructure investment in Brazil. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2018, 2, 301–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, K. Trickle down? Private sector participation and the pro-poor water supply debate in Jakarta, Indonesia. Geoforum 2007, 38, 855–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J. The pitfalls of water privatization: Failure and reform in Malaysia. World Dev. 2012, 40, 2552–2563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Malaluan, N.A. A tale of two concessionaires: A natural experiment of water privatisation in Metro Manila. Urban Stud. 2008, 45, 207–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, L.T.; Gleason, E.S. Is foreign infrastructure investment still risky? Harv. Bus. Rev. 1995, 73, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Basılio, M. Infrastructure PPP Investments in Emerging Markets. Available online: https://www.efmaefm.org/0EFMAMEETINGS/EFMA%20ANNUAL%20MEETINGS/2011-Braga/papers/0337_update.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2025).

- Jiang, W.; Martek, I.; Hosseini, M.R.; Chen, C.; Ma, L. Foreign direct investment in infrastructure projects: Taxonomy of political risk profiles in developing countries. J. Infrastruct. Syst. 2019, 25, 04019022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Martek, I.; Hosseini, M.R.; Chen, C. Political risk management of foreign direct investment in infrastructure projects: Bibliometric-qualitative analyses of research in developing countries. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2021, 28, 125–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Xiong, W.; Song, J. The moderating role of governance environment on the relationship between risk allocation and private investment in PPP markets: Evidence from developing countries. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2019, 37, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, O. Public–private partnerships for water in Asia: A review of two decades of experience. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2017, 33, 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, A.; Botton, S. Water Services and the Private Sector in Developing Countries: Comparative Perceptions and Discussion Dynamics; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J.; Chung, J.; Lee, D.J. Risk perception analysis: Participation in China’s water PPP market. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2010, 28, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Wang, S.; Chan, A.P.; Lam, P.T. Preferred risk allocation in China’s public–private partnership (PPP) projects. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2010, 28, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Ke, Y.; Lin, J.; Yang, Z.; Cai, J. Spatio-temporal dynamics of public private partnership projects in China. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 1242–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, A.; Chan, T.K.; Aibinu, A.A.; Chen, C.; Martek, I. Risk allocation inefficiencies in Chinese PPP water projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 04018013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braadbaart, O.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y. Managing urban wastewater in China: A survey of build–operate–transfer contracts. Water Environ. J. 2009, 23, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Development of public private partnership (PPP) projects in the Chinese water sector. Water Resour. Manag. 2010, 24, 1925–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayliss, K.; Hall, D.; Corral, V.P. FDI Linkages and Infrastructure: Some Problem Cases in Water and Energy; Public Services International Research Unit (PSIRU): London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- EU SME Centre. The Water Sector in China. 2013. Available online: https://www.eusmecentre.org.cn/publications/the-water-sector-in-china/ (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Dykes, B.J.; Uzuegbunam, I. Foreign partner choice in the public interest: Experience and risk in infrastructure public–private partnerships. J. Int. Bus. Policy 2022, 6, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.H.; Rugman, A.M. Firm-specific advantages, inward FDI origins, and performance of multinational enterprises. J. Int. Manag. 2012, 18, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebeiz, K.S. Public–private partnership risk factors in emerging countries: BOOT illustrative case study. J. Manag. Eng. 2012, 28, 421–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadi, C.; Carrillo, P.; Tuuli, M. PPP projects: Improvements in stakeholder management. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2020, 27, 544–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, F.A. Financing irrigation water management and infrastructure: A review. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2010, 26, 321–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgomeo, E.; Kingdom, B.; Plummer-Braeckman, J.; Yu, W. Water infrastructure in Asia: Financing and policy options. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2023, 39, 895–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Choi, Y. A comparative study of the adoption of public-private partnerships for water services in South Korea and Singapore. Public Adm. Policy 2023, 26, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. Expansion of the Private Sector in the Shanghai Water Sector; Occasional Paper No.53; University of London: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, J.W.; Howe, C.W. Key issues and experience in US water services privatization. In Water Pricing and Public-Private Partnership; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 87–96. [Google Scholar]

- Hart, O. Incomplete contracts and public ownership: Remarks, and an application to public-private partnerships. Econ. J. 2003, 113, C69–C76. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, H.; Zeng, S.; Lin, H.; Zeng, R. Impact of public sector on sustainability of public–private partnership projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2020, 146, 04019104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladağ, H.; Işik, Z. The effect of stakeholder-associated risks in mega-engineering projects: A case study of a PPP airport project. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2018, 67, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estache, A. PPI partnerships vs. PPI divorces in LDCs. Rev. Ind. Organ. 2006, 29, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Zhao, Z.J. Cost-Saving or Cream-Skimming? Partner Ownership and the Project Returns of Public-Private Partnerships in China. J. Chin. Political Sci. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Pandey, C.M.; Singh, U.; Gupta, A.; Sahu, C.; Keshri, A. Descriptive statistics and normality tests for statistical data. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2019, 22, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhong, L.; Mol AP, J.; Fu, T. Public-private partnerships in China’s urban water sector. Environ. Manag. 2008, 41, 863–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi, H.; Cui, C. Coping with functional collective action dilemma: Functional fragmentation and administrative integration. Public Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 1052–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhao, W.; Li, Q.; Cai, H. Embeddedness and contractual relationships in China’s transitional economy. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2003, 68, 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, M.; Mu, R.; Stead, D.; Ma, Y.; Xi, B. Introducing public–private partnerships for metropolitan subways in China: What is the evidence? J. Transp. Geogr. 2010, 18, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. Selling China: Foreign Direct Investment During the Reform Era; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hillman, A.J.; Withers, M.C.; Collins, B.J. Resource dependence theory: A review. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 1404–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Luo, Y.; Xia, J.; Hitt, M.; Shen, J. Resource dependence theory in international business: Progress and prospects. Glob. Strategy J. 2023, 13, 3–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G. External Control of Organizations—Resource Dependence Perspective. Organizational Behavior 2; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 355–370. [Google Scholar]

- Drees, J.M.; Heugens, P.P. Synthesizing and extending resource dependence theory: A meta-analysis. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 1666–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundonde, J.; Makoni, P.L. Framework Model for Financing Sustainable Water and Sanitation Infrastructure in Zimbabwe. Water 2024, 16, 1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chan AP, C.; Feng, Y.; Duan, H.; Ke, Y. Critical review on PPP Research–A search from the Chinese and International Journals. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016, 34, 597–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Zhao, J.Z. The rise of public–private partnerships in China: An effective financing approach for infrastructure investment? Public Adm. Rev. 2019, 79, 514–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng PJ, H. Adequate, resilient and sustainable: How to run a water utility in a pandemic. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2022, 38, 351–354. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F. A decade of tax-sharing: The system and its evolution. Soc. Sci. China 2006, 6, 100–115. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, F.; Martek, I.; Chan, A.P.; Chen, C.; Yang, Y.; Yu, H. Assessing the public-private partnership handover: Experience from China’s water sector. Util. Policy 2023, 80, 101469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Zheng, X. Private sector participation and performance of urban water utilities in China. Econ. Dev. Cult. Change 2014, 63, 155–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, J. Middle East Water Question—Hydropolitics and Global Economy; IB Tauris: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Global Water Intelligence. Managing China’s Asset Price Inflation. Available online: https://www.globalwaterintel.com/global-water-intelligence-magazine/8/3/general/managing-china-s-asset-price-inflation (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Zhao, J.Z.; Su, G.; Li, D. Financing China’s unprecedented infrastructure boom: The evolution of capital structure from 1978 to 2015. Public Money Manag. 2019, 39, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Tortajada, C. Innovative and transformative water policy and management in China. Int. J. Water Resour. Dev. 2020, 36, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.Y.; Chen, S. Transitional public–private partnership model in China: Contracting with little recourse to contracts. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2016, 142, 05016011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Leiringer, R. Closing capability gaps for procuring infrastructure public-private partnerships: A case study in China. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2023, 41, 102497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Gao, Y.; Feng, Z.; Sun, W. PPP application in infrastructure development in China: Institutional analysis and implications. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2015, 33, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohemeng, F.L.; Grant, J.K. Has the bubble finally burst? A comparative examination of the failure of privatization of water services delivery in Atlanta (USA) and Hamilton (Canada). J. Comp. Policy Anal. Res. Pract. 2011, 13, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammami, M.; Ruhashyankiko, J.F.; Yehoue, E.B. Determinants of Public-Private Partnerships in Infrastructure; IMF Working Paper No. 2006/99; World Bank Group: Washinton, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gulati, R. Does familiarity breed trust? The implications of repeated ties for contractual choice in alliances. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledeneva, A. Blat and guanxi: Informal practices in Russia and China. Comp. Stud. Soc. Hist. 2008, 50, 118–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Zhong, N.; Wang, F.; Zhang, M.; Chen, B. Political opportunism and transaction costs in contractual choice of public–private partnerships. Public Adm. 2022, 100, 1125–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO, UN-Water. United Nations World Water Development Report 2020: Water and Climate Change; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020; Available online: https://www.unwater.org/publications/un-world-water-development-report-2020 (accessed on 29 January 2025).

- Bai, M.; Cai, J.; Qin, Y. Ownership discrimination and private firms financing in China. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2021, 57, 101406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Li, D.; Man, C. Toward sustainable development? A bibliometric analysis of PPP-related policies in China between 1980 and 2017. Sustainability 2018, 11, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).