Failure Characteristics and Stress Distribution of Intact Floor Under Coupled Static and Dynamic Loads in Mining Projects

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Geological and Geotechnical Setting

3. Theoretical Analysis

3.1. Mechanical Model of Mining Floor Under Combined Action of Dynamic and Static Loads

3.2. Theoretical Calculation Method

3.2.1. Stress Fields from Static Load

3.2.2. Stress Fields from Dynamic Load

3.3. Dynamic Response Characteristics of Mining Floor

3.4. Floor Failure Depth and Characteristics

4. Numerical Simulation and Field Measurement

4.1. Numerical Model and Simulation Results

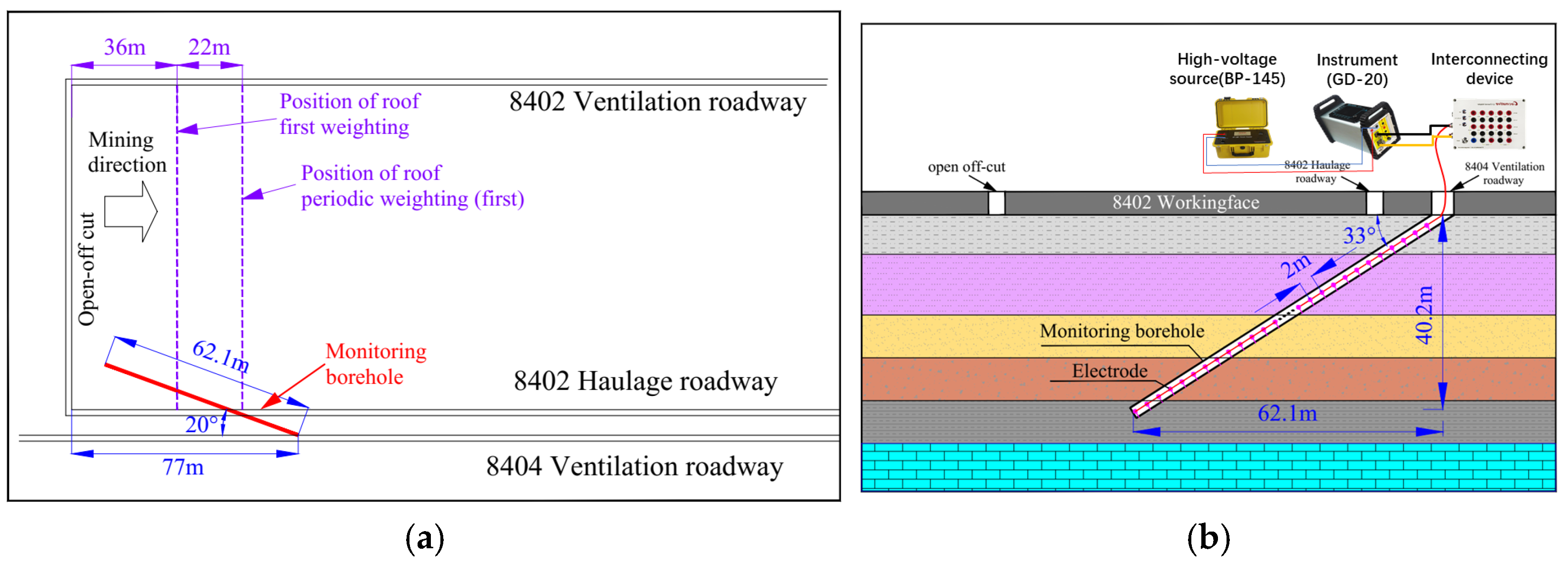

4.2. Field Measurement

5. Discussion and Conclusions

- (1)

- Considering the coal seam floor under the combined effects of the dynamic loads induced by roof breakage and the static loads induced by abutment pressure, a new mechanical method that comprehensively considers the effect of dynamic disturbance on the floor is established to theoretically calculate the floor stress field and FDMF. With a comprehensive consideration of the mining floor under multi-stress conditions in the proposed model, the obtained results are more realistic than those obtained using traditional methods.

- (2)

- The theoretical analysis results reveal that the stress field of the floor demonstrates distinct dynamic characteristics due to the dynamic loads induced by roof weighting. These findings indicate that dynamic loads significantly influence vertical and shear stresses, while their effect on horizontal stress is minimal. Moreover, the dynamic load complicates the variation characteristics of the floor stress fields more than static load action alone. The dynamic loading expands the stress concentration zone and intensifies the degree of stress concentration of the mining floor, inevitably leading to a further increase in the maximum FDMF.

- (3)

- To verify the accuracy of the proposed model, numerical simulations and field measurements were carried out. A comparative analysis of the results obtained from the above three methods is summarized in Table 3.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, J.; Xu, Q.; Hu, Y.; Chen, X. Evaluation of Control Effect of Confined Water Hazard in Taiyuan Formation Coal Seam Mining in Huanghebei Coalfield. Water 2023, 15, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Zhao, C. Evolution of Water Hazard Control Technology in China’s Coal Mines. Mine Water Environ. 2021, 40, 334–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Y.; Zuo, J.P.; Wei, C.C.; Xu, X.; Zhou, Z.Q.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Fracture Development at Laminated Floor Layers Under Longwall Face in Deep Coal Mining. Nat. Resour. Res. 2020, 29, 3857–3871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Y.; Zuo, J.P.; Huang, X.H.; Wu, G.S.; Li, Y.B.; Xing, S.K. Water Inrush Modes Through a Thick Aquifuge Floor in a Deep Coal Mine and Appropriate Control Technology: A Case Study from Hebei, China. Mine Water Environ. 2022, 41, 954–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.L.; Bai, H.B. Simulation Research on the Mechanism of Water Inrush from Fractured Floor under the Dynamic Load Induced by Roof Caving: Taking the Xinji Second Coal Mine as an Example. Arab. J. Geosci. 2019, 12, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.L. Green Mining of Coal Mine; China University of Mining and Technology Press: Xuzhou, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.P.; Li, X.Q.; Sun, R.H. Preliminary Study on Dynamic Water Inrush of Coal Mining Under Super-Thick Hard Rock. J. Eng. Geol. 2008, 16, 446–450. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.Y. Fracture Mechanism and Its Model of Floor Rock Mass under Stong Disturbance in Deep Coal Mining. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Mining & Technology(Beijing), Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D. Study on Deformation and Failure Mechanism of Deep Coal Seam Floor in Xingdong Mining Area. Ph.D. Thesis, Chang’an University, Xi’an, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Y.Q. Investigation on the Mechanism of Water Inrush in 15423N Working Face of Jiulong Coal Mine. Coal Sci. Technol. 2012, 40, 105–108. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, Y.P.; Li, G.C.; Li, H.G. Fast Plugging Water Inrush of Ordovician Limestone in No. 81004 Working Face. In Proceedings of the Excellent Academic Proceedings in 2004 of Shandong Institute of Coal; Jinan Press: Jinan, China, 2004; pp. 185–190. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, D.W. Analysis of Water Inrush in the 12 and 13 Mining Areas of JiuLiShan Mine. Coal 1998, 7, 59–61. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, P.; Jiang, L.S.; Jiang, J.Q.; Wu, Y.N.; Chen, L.J.; Ning, J.G. Numerical Analysis of Roadway Rock-Burst Hazard under Superposed Dynamic and Static Loads. Energies 2019, 12, 3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.H.; Zhu, S.Y.; Cao, S.W.; Zhang, M. Study of Floor Failure Characteristics and Water-Inrush Risk in a Working Face of Lower Coal Seam. Arab. J. Geosci. 2022, 15, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.F.; Jiang, F.X.; Zhu, S.T.; Yang, G.Y. Mechanism of Integrated Dynamic Disaster of Rockburst and Water Inrush: A New Type of Integrated Dynamic Disaster in China. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2017, 35, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.L.; Cao, J.J.; Tu, M. Floor Stress Evolution Laws and Its Effect on Stability of Floor Roadway. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2013, 23, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Jiang, B.S. Analytical Solution for Stress and Deformation of the Mining Floor Based on Integral Transform. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2015, 25, 581–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.S.; Cheng, J.L. Analytical Model of Stress Field and Failure Depth in Multilayered Rock Masses of Mining Floor Based on the Transfer Matrix Method. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2017, 35, 2781–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Z.; Guo, P.G.; Yuan, A.Y.; Zhu, C.Q.; Zhang, T.; Chen, D.H. Failure Characteristics Induced by Unloading Disturbance and Corresponding Mechanical Mechanism of the Coal-Seam Floor in Deep Mining. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Hu, Y.; Zhao, G.M. Relationship between Water Inrush from Coal Seam Floors and Main Roof Weighting. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2017, 27, 873–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.B.; Hebblewhite, B.K.; Galvin, J.M. Analytical Solutions for Mining Induced Horizontal Stress in Floors of Coal Mining Panels. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2000, 184, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Jiang, L.S.; Ma, C.Q.; Yuan, A.Y. Evolution Laws of Floor Stress and Stability of Floor Roadway Affected by Overhead Mining. Earth Sci. Res. J. 2020, 24, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.X.; Liu, W.T.; Zhao, J.Y.; Ding, X.Y. In Situ Investigation and Numerical Simulation of the Failure Depth of an Inclined Coal Seam Floor: A Case Study. Mine Water Environ. 2019, 38, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.L.; Wang, L.G. Numerical Simulation of Mining-Induced Fracture Evolution and Water Flow in Coal Seam Floor above a Confined Aquifer. Comput. Geotech. 2015, 67, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Ding, X.S.; Yu, Z.Z.; Wang, M.; Mu, Q.; Dai, Z.X.; Li, H.Y.; Zhang, B.; Han, T.R. Prediction Model of Fracture Depth and Water Inrush Risk Zoning in Deep Mining Coal Seam Floor. Environ. Earth Sci. 2022, 81, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yang, Z.; Wang, S.; Ren, L.; Fang, J. The Effects of Coal Floor Brittleness on the Risk of Water Inrushes from Underlying Aquifers: A Numerical Study. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.L.; Meng, Z.B. Experimental Study on Floor Failure of Coal Mining above Confined Water. Arab. J. Geosci. 2019, 12, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.Y.; Lefticariu, L.; Wei, J.C.; Guo, J.B.; Li, Z.J.; Guan, Y.Z. In Situ Dynamic Monitoring of Stress Revolution with Time and Space under Coal Seam Floor during Longwall Mining. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.L.; Zhang, P.S.; Wu, R.X.; Hu, X.Y. Dynamic Monitoring the Deformation and Failure of Extra-Thick Coal Seam Floor in Deep Mining. J. Appl. Geophys. 2019, 163, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.F.; Zhao, L.J.; Chen, Y. Effect of Floor Failure in Fully Mechanized Caving of Extra-Thick Coal Seam in Datong Mining Area. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Zhang, J.; Lin, H.; Liu, H.; Gao, S.; He, Y. The Catastrophic Failure Mechanisms and the Prevention of Dynamic Pressure-Related Hazards during Mining under an Interval Goaf through an Isolated Coal Pillar in Shallow and Closely Spaced Coal Seams. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.C.; Wu, J.; Xu, Z.H.; Yang, W.M. Mechanics Criterion of Water Inrush from the Coal Floor under Influence of Fault and Its Engineering Application. Int. J. Geomech. 2019, 19, 04019022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.J.; Peng, S.P.; Xiang, S.Y.; Liang, M.X.; Liu, W.M. The Effects of Caving of a Coal Mine’s Immediate Roof on Floor Strata Failure and Water Inrush. Mine Water Environ. 2016, 35, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Yin, S.; Li, S.; Wang, X. Mechanisms of Thick-Hard Roof and Thin Aquifer Zone Floor Destruction and the Evolution Law of Water Inrush. Water 2024, 16, 2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.K.; Wan, Z.J.; Yang, Y.J.; Wang, J.H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.F. Failure Characteristics and Stability Control Technology of Dynamic Pressure Roadway Affected by the Mining Activity: A Case Study. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2022, 131, 105857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Dou, L.M.; Si, G.Y.; Hu, Y.W. Fault-Induced Coal Burst Mechanism under Mining-Induced Static and Dynamic Stresses. Engineering 2021, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.Y.; Sang, S.Z.; Xie, D.L.; Zhao, H.; Li, S.J.; Li, H.S.; Zhuang, X.H. A Numerical Simulation Technique to Study Fault Activation Characteristics during Mining between Fault Bundles. Environ. Earth Sci. 2019, 78, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sequence Number | Coal Mine Name | Description of Water Inrush | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Shigu coal mine | Three FWI accidents occurred when working face advanced to the position of roof first or periodic weighting in 9304 working face. | [6] |

| 2 | Zhaogezhuang coal mine | A delayed floor fault water inrush accident occur at in the third mining level. And accompanied by rockburst accident. | [7] |

| 3 | Zhaogu No.1 coal mine | FWI accidents occurred at 12,041 working face in Xierpan mining area during the period of roof first weighting, with the maximum water flow approximately 486 m3/h. And new water inrush channels formed during the periods of roof periodic weighting | [8] |

| 4 | Xingdong coal mine | 2011.04~2015.05, FWI occurred at 2125, 2126, 2222 and 2228 working face at mining level −980 m. Those accidents correlate between FWI and periodic weighting. | [9] |

| 5 | Jiulong coal mine | Three water inrush accident happened in 15,423 N working face. Due to the periodic roof weighting, second FWI incident occurred accompanied by the floor heave. | [10] |

| 6 | Caozhuang coal mine | In March 2004, FWI occurred after a strong roof weighting when 81,004 working face advanced to 360 m. And the maximum amount of water inrush is approximately 403 m3/h. | [11] |

| 7 | Jiulishan coal mine | FWI accidents occurred at the position of first roof weighting when the working face advanced about 20 m in 12,031, 12,021, 12,011 working faces of mining area 12. | [12] |

| Lithology | Thickness/(m) | Elastic Modulus/ (GPa) | Poisson Ratio | Friction Angle/ (°) | Cohesion/(MPa) | Tensile Strength/ (MPa) | Density/ (kg·m−3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overlying rock | 14.9 | 30.79 | 0.27 | 35 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 2500 |

| Fine sandstone | 25.5 | 29.18 | 0.26 | 34 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 2630 |

| Mudstone-1 | 4.2 | 23.50 | 0.28 | 33 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 2570 |

| Medium sandstone | 28.6 | 18.50 | 0.25 | 34 | 4.5 | 2.8 | 2700 |

| No.8 coal seam | 3.5 | 13.08 | 0.23 | 23 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 1620 |

| Mudstone-2 | 8.5 | 16.97 | 0.28 | 24 | 2.2 | 1.4 | 2540 |

| Siltstone | 15.4 | 18.01 | 0.25 | 26 | 2.8 | 1.7 | 2650 |

| Gritstone | 24.6 | 21.51 | 0.25 | 29 | 3.1 | 2.3 | 2720 |

| Limestone | 10.8 | 35.74 | 0.23 | 37 | 4.5 | 2.6 | 2450 |

| Bottom rock | 14 | 44.21 | 0.20 | 39 | 5.6 | 2.8 | 2760 |

| Before Roof First Weighting | After Roof First Weighting | After Roof Periodic Weighting (First) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical calculation | 14.8 m | 20.8 m | |

| Numerical simulation | 15.7 m | 20.8 m | 22.9 m |

| Field measurement | 12.2 m | 21.4 m | 23.4 m |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, Q.; Xu, B.; Feng, J.; Peng, J.; Wang, X. Failure Characteristics and Stress Distribution of Intact Floor Under Coupled Static and Dynamic Loads in Mining Projects. Water 2025, 17, 699. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17050699

Huang Q, Xu B, Feng J, Peng J, Wang X. Failure Characteristics and Stress Distribution of Intact Floor Under Coupled Static and Dynamic Loads in Mining Projects. Water. 2025; 17(5):699. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17050699

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Qisong, Bo Xu, Junjun Feng, Jun Peng, and Xiangyu Wang. 2025. "Failure Characteristics and Stress Distribution of Intact Floor Under Coupled Static and Dynamic Loads in Mining Projects" Water 17, no. 5: 699. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17050699

APA StyleHuang, Q., Xu, B., Feng, J., Peng, J., & Wang, X. (2025). Failure Characteristics and Stress Distribution of Intact Floor Under Coupled Static and Dynamic Loads in Mining Projects. Water, 17(5), 699. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17050699