This section outlines the findings from the key informant interviews conducted regarding the successes and challenges of the CWA and implications of the

Act on the capacity for SWP in particularly rural areas. For the purposes of this paper, findings have been derived for municipalities with public drinking water systems that were included in the source protection plans for the CSPA and the NBMSPA. Therefore, the findings exclusively apply to serviced municipalities (i.e., municipalities with drinking water systems owned by the municipality).

Table 2 provides a summary for the presence of or absence of all elements of capacity according to region. Further explanations of these findings are described in subsequent sections.

Table 2 outlines the percentage of interviews that discussed either the presence or absence of the element of capacity. Many informants confirmed both the presence and absence of an element. Below in

Table 2,

n represents the number of interviews which discussed the element (not all interviewees discussed each element as they did not have expertise or experience in that area and could not therefore answer the interview questions relating to the element). Indicators used to assess presence or absence of an element can be found in

Table A1. To further support overall findings, tables have been provided in

Section 3.1,

Section 3.2,

Section 3.3 and

Section 3.4 denoting how many participants supported each major finding related to each element of SWP capacity.

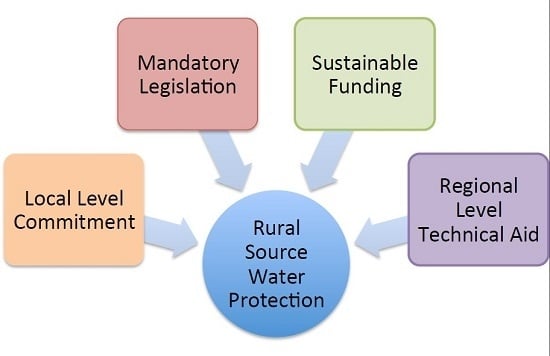

3.1. Institutional

Institutional capacity for SWP refers to the legislation, regulations, policies, protocols, governance arrangements and delegation of responsibility to plan and enact SWP [

12,

20]. In total, 29/30 interviews conducted discussed institutional capacity for SWP under the CWA. All of these participants noted the process under the CWA as successful in raising institutional capacity for the municipalities included in the source protection plans (

Table 2). Firstly, 24 participants noted the enforceable and mandatory nature of the CWA legislation itself as integral to raising the institutional capacity for SWP (

Table 3). The Walkerton tragedy, and the subsequent

Walkerton Inquiry [

3,

4] was noted by 20 participants as the driving force for stricter legislation for safe and clean drinking water in Ontario. Twenty informants explained that the CWA legislation and associated regulations delineated governance processes and protocols for how to create source protection plans and roles within implementation (

Table 3). For example, the source protection committees were regulated through Ontario regulation 288/07 of the CWA. The governance choice to have the conservation authorities as the source protection authority was a natural fit, as conservation authorities already had experience working with municipalities at a watershed level. Source protection committee members had to go through an interview process, and conservation authorities appointed committee members. Agricultural representatives appointed by the conservation authorities were elected in local elections facilitated by the Ontario Farm Environmental Coalition and the County Federations of Agriculture. Chairs were appointed by the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change. The source protection committee had a good mix of actors, representing a diverse range of views (social, economic and environmental). One SPC Participant explained that the committee, “

…was a good opportunity to network and exchange ideas and you know … put me in touch with some of the folks that I wouldn’t normally be in touch with” (SPC Participant). The process allowed for ample discussion and debate, with topics of concern spanning meetings, and often requiring additional research by the source protection authorities and provincial liaisons. All decisions were based on consensus.

As discussed above, the CWA was noted by 24 participants as particularly effective in giving the created source protection plans the needed legislative power to be enforced through clear implementation responsibilities and consequences, such as Official Plan and by-law conformity [

17] (

Table 3). In the creation of the source protection plans, the source protection committees strategically evaluated where gaps in current legislation existed. The policies under the plan aimed to fill these gaps. In addition to the CWA, other complementing legislation ensures implementation of SWP policies. These other prescribed instruments issued by the provincial government that contain provisions that can be used in SWP include the:

Environmental Protect Act (1990);

Ontario Water Resources Act (1990);

Pesticides Act (1990); Safe Drinking Water Act (2002); Aggregate Resources Act (1990); Nutrient Management Act (2002) [

31]. Instruments that are enabled under Ontario legislation that are relevant to source protection planning are listed in

Table 4. For example, Section 19 of the

Safe Drinking Water Act (2002) outlines a statutory standard of care that requires those persons that have decision-making authority over municipal drinking water systems to act honestly, competently and with integrity when making decisions regarding municipal drinking water systems. Responsible parties (including municipal councillors) can be prosecuted and convicted under this section [

33].

Binding policies were created in the source protection plans for each region including efforts such as outreach and education, raw quality samplings, and emergency and spill response plans [

30,

31]. The types of policies were outlined in the plans along with rationales, prescribed legal effects by tools, and prescribed instrument decisions that must conform to a policy (e.g., Official Plans). It should be noted not all policies created in the source protection plans were mandatory. The types of policies range from: must conform/comply with policies; have regard to policies; and non-legally binding policies. In short, a must conform/comply policy is instituted to address a significant drinking water threat/condition, as outlined in the plan [

30,

31]. Though the non-legally binding policies have no legal impact, there was indication from a provincial government staff member that the Minister of Environment and Climate Change read and is considering all non-binding policies. One provincial government staff member explained in regard to the non-binding policies included in the plans, “

Their needs to be a rationale for why we are not implementing that. So kudos to the people that really did push the boundaries for us because it really does highlight for us that we could be doing a better job in certain areas” (Provincial Participant). This indicates the inclusion of the non-binding policies were not done in vain by the source protection committees, and could lead to regulatory reform in the future.

Part IV of the CWA lays out the regulation of drinking water threats identified in the source protection plans and the various roles in enforcement shared between municipalities, boards of health, planning boards, source protection authorities, and provincial actors. Mechanisms for implementation are also included in the CWA legislation regarding monitoring programs and annual progress reports. Twenty key informants noted that even though they may not agree with decisions made in source protection plans, all implementers of the plans have clear responsibilities, and know their obligations in implementation (

Table 3). The source protection authorities (i.e., the conservation authorities) as well as the risk management officials play an important role in monitoring and enforcement efforts. The risk management official and inspector help address legally binding policies under the source protection plan, and work with implementers (e.g., municipalities, businesses, landowners) to ensure policies are being followed. It was explained by a rural municipal Risk Management Official on the role, “

basically I’ll ask you really nicely to do it. Then I’ll tell you to do it, then I will order you to do it. And if you don’t do it on our order I will do it and put it on your tax ill” (Municipal Participant). Evidently, there are clear steps to ensure the “must conform” policies under the source protection plans are abided by. However, as will be discussed in subsequent sections, there was some concern expressed by key informants regarding funding for further iterations of the plan and the same level of continued support for implementation measures.

Annual progress reports are collected by conservation authorities and submitted to the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change. Conservation authorities are also able to submit letters to the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change on items to consider in future plan reviews and iterations. Nine participants noted this first round of planning was rolled out in stages, causing source protection committees and authorities to go back and re-evaluate decisions or re-do certain activities related to the assessment report to address refinements to the Tables of Drinking Water Threats. (The Tables of Drinking Water Threats is a document issued by the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change and contains a series of tables of potential drinking water threats. The document identifies under which circumstance the listed drinking water threats can be categorized in the source protection plans as a significant, moderate or low drinking water threat [

30].) The narrowing scope of the work as the program rolled out was often a source of frustration for source protection committee members (

Table 3). This resulted in much inefficiency in the planning process. One municipal staff member said, “

…it was a little bit like two steps forward, three steps back” (Municipal Participant). Another Conservation authority staff member said,

“We weren’t always 100% sure about some of the technical rules for the assessment work, and those are actually being reviewed right now by the province, which is good. In any kind of process the first phase, the first step is your base model and then you make iterative improvements and we are pleased to see that the province is going to make improvements for the second round. Things are going to be better and better”.

(CA Participant)

There is positivity regarding the next round of planning, and hopes that it will be more clearly scoped as the program matures.

As mentioned, the majority of participants (24) noted having SWP legislated under the CWA was beneficial in raising institutional capacity (

Table 3). However, there were also concerns regarding the prescriptive nature of the CWA and ways in which the CWA restricted the planning process and local autonomy in deciding what could be included in the source protection plans. For example, the Tables of Drinking Water Threats were important in making decisions technically defensible. However, 22 participants noted the process being overly rigid and sometimes insensitive to specific local issues and circumstances (

Table 3). One such example is the ability to address issues with Great Lakes intakes in the CSPA. Another example includes allowing the Energy East pipeline to be considered a threat in the NBMSPA. Though there was some flexibility for local circumstance and to add local threats to the list of prescribed activities needing to be addressed, it did not always cover every circumstance. On the other hand, the plans had to include legally binding policies for municipalities for threats that would never be able to occur in the areas designated or would require policies that were redundant. For example, a municipal staff member explained,

“… airplane de-icing, salt and storage, winter snow storage that were identified as threats and that we zoned for. None of those activities would even be able to occur in the IPZ-1 or 2 areas. Because it is basically just a shoreline in the urban area so you get into the threats for the issue contributing area a little bit more possibly there. So, the ones in town, I mean that area is already developed and not getting any kind of airport anytime”.

(Municipal Participant)

The exclusion of certain communities from the mandatory protection of the CWA was noted by 25 key informants as a shortcoming of the legislation (

Table 3). As of now First Nation communities, municipally serviced systems outside of current source protection areas/regions, and those drinking water systems not part of municipally owned drinking water systems (e.g., private wells, private surface water systems) were excluded from requiring mandatory source protection under the CWA. There were no First Nation communities located in the CSPA. In the NBMSPA the Nipissing First Nation decided not to be part of the process. One provincial government participant explained there is currently a mandate at the provincial level for better inclusion of First Nations in the process. There is the ability to elevate either a First Nation community or a clustering of wells into source protection plans under the CWA [

17]. In the NBMSPA, they did choose to elevate a private well clustering in the community of Trout Creek (which has now been amalgamated into the Municipality of Powassan) into their plan. However, the town fought to opt-out of the process in the end. This was due to a variety of reasons, mainly concerns of house resale values if their well to septic bed distance was labeled as a significant drinking water threat. Though the plans did not intentionally mandate protection for private drinking water sources, some of these sources were protected due to their location within a municipal vulnerable area. For example, if a private well fell within a vulnerable area of a municipal drinking water intake, there were legally enforceable measures under the source protection plans and other legislation protecting this source. For example, the

Building Code Act, 1992 and the Building Code require mandatory maintenance inspections of every on-site sewage system (e.g., septic system) in vulnerable areas where these systems are identified as significant threats to a source of drinking water (e.g., wellhead protection areas A and B) [

30]. The legislation does allow for planned municipal water systems to be elevated into the plan.

The process under the CWA did raise the institutional capacity for SWP in rural communities in the source protection areas, most notably for creating plans that had policies that must be implemented. It was mentioned by 11 participants, especially for small rural communities with limited financial capacity and staff, that voluntary actions are often not implemented. Ultimately, institutional measures such as enforceable legislation and guiding governance structures are needed in SWP, and were strongly displayed in the process under the CWA.

3.2. Financial

Financial capacity for SWP refers to the ability to acquire adequate funds to pay for SWP efforts as well as for ongoing planning, governance and management efforts [

12,

20]. In total, 27/30 interviews conducted discussed financial capacity for SWP under the CWA. As highlighted in

Table 2, evidence of the presence of financial capacity was strong in each case study region, and indicated as present from the Ontario wide informants. The majority of comments indicating a presence of financial capacity referred to the funding available during the planning process and in the creation of the terms of reference, the assessment report, and the source protection plans themselves (

Table 5). Provincially, the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change have invested over

$250 million in the program thus far [

19]. It was explained by a municipal staff member, “

The province paid for everything. So they paid through the conservation authorities, the conservation authorities hired the consultants. The township didn’t have to pay anything beyond the staff time to review and implement” (Municipal Participant). Provincial funding programs such as the Source Protection Municipal Implementation Fund was imperative in funding both voluntary and mandatory implementation efforts (including staffing costs). This funding was noted by six participants as being especially important for rural municipalities that would not have been able to achieve delegated duties without additional resources. Municipal key informants noted that, thus far in these early stages of implementation, SWP under the CWA has not been a financial burden on them as there has been sufficient provincial funding. Landowners who implement plan policies have also been provided with funding through the Ontario Drinking Water Stewardship fund that helped with efforts such as septic system replacements and the general outreach and education of people that were going to be impacted by the source protection plans. There have also been specific funding programs for farmers and support from the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs through their nutrient management legislation and plans. However, one participant expressed some concerns about this funding being very competitive and requiring a farm plan, resulting in individuals having to apply a couple times before funding was granted.

Despite strong consensus regarding the presence of financial capacity for the process under the CWA, there were also less frequent comments regarding the absence of financial capacity. For example, 16 participants expressed concern about the impacts of unknown future funding from the provincial government for implementation, monitoring and evaluation of source protection plans (

Table 5). It was explained in the Cataraqui Source Protection Plan,

“most municipalities stressed their unwillingness to implement policies, especially non-legally binding policies, unless there is provincial funding and other resources made available to do so. Concerns were also raised by local residents that could be impacted by the Plan”

In the village of Mallorytown in the CSPA, there was significant push back from residents and municipal officials on implementing SWP policies for a 17-unit apartment building obtaining water from a well. The building and the well are both owned by the United Counties of Leeds and Grenville, therefore triggering the CWA legislation, as a public water system [

30]. One source protection committee member explained that the concerns were mainly due to financial implications of implementation such as changes to septic fields, upgrades to oil tanks, and impacts on future development. With ongoing implementation funding unknown, this impacted some of the decisions that the source protection committees made. For example, one source protection committee member explained, “

We specifically did not go down the path of having a risk management officer. You know because had that happened then that would have been costs to all of the municipalities, that there was no funding for” (SPC Participant). As noted in the previous section, the community containing the cluster of private wells that were elevated into the source protection plan in the NBMSPA was also concerned about implementation costs and implications on housing prices. Under the CWA, municipalities are responsible for implementing policies and funding risk management officials. This research shows that financial ownership by municipalities may be lacking, especially for those rural municipalities in the case study regions.

It was clear that municipalities with supportive councils that prioritized water were more optimistic about implementation. One consultant stated, “

…if you want to have a safe water supply you have to be prepared to pay for it” (Other Participant). However, municipal ownership of the full fiscal responsibilities of SWP was not always the case. Six participants indicated financial ownership of the program is lacking at the municipal level, especially in rural municipalities (

Table 5). One conservation authority staff member explained,

“They are trying to instill a sense of ownership in the municipalities. It is your drinking water, your people, you help protect it from source to tap. But at least in our area the municipal councils still see it as a shared responsibility with ongoing provincial funding and support”.

(CA Participant)

Clearly, municipalities are still relying on provincial government support for SWP. A concern that will be outlined more in

Section 3.4 is the impact that diminished funding has had on staff retention at the conservation authorities. Six participants expressed the loss of human capacity at the conservation authorities as a concern resulting from a loss of financial capacity (

Table 5). These lost conservation authority staff held the institutional knowledge of the SWP planning process and were important actors in aiding municipalities in implementation. One conservation authority staff member mentioned the importance of being creative with funding and staff roles, engaging staff on other mandates so they are not lost. This issue speaks to the larger issue of how reduced financial capacity will impact institutional, technical/human and social capacity for SWP. This reduced capacity due to declining provincial funding is especially concerning for small rural municipalities who lack internal staff for SWP efforts.

Though provincial funding is not guaranteed into the future, a provincial staff representative explained that the CWA and SWP in general is “

embedded in the way we do business” (Provincial Participant). This does suggest that there will be the availability of some continued funding for municipalities in the future. During the annual reviews conducted by conservation authority staff, future SWP research and activities are prioritized and funding is requested from the provincial government for these activities. This funding is currently on a year-by-year basis. Regarding funding for SWP, one conservation authority staff member explained, “

Is there enough? There is never enough. And the more you learn the more you find you need to do” (CA Participant). One conservation authority staff member explained in regard to rural municipalities,

“small rural communities often have less capacity and financial resources to assess conditions and threats to their drinking water supplies on an ongoing basis. They generally rely more on the Province to assist in protecting the residents. Some find efficiencies by pooling resources with other nearby communities”.

(CA Participant)

Into the future, further attention will be needed for sustainable fiscal frameworks for SWP implementation at the municipal level. This will be increasingly difficult for rural municipalities, and will require a great deal of prioritization of such efforts, in already limited budgets.

3.3. Social

Social capacity for SWP refers to the social factors that influence SWP governance and implementation. This includes social norms (e.g., values, attitudes, behaviours, sense of place, trust, reciprocity, commitment and motivation) that impact public awareness, stakeholder involvement, community support, and public and private partnerships in SWP efforts. This also incorporates structural networks, communications and the relationships between different interest groups and actors [

12,

20]. In total, 22/30 interviews conducted discussed social capacity for SWP under the CWA, with most of the interviews displaying high levels of social capacity elements (

Table 2). When considering factors in social capacity such as leadership at the watershed level, the conservation authorities acting as the source protection authority served a vital function as the regional experts. The conservation authorities played both the role of a facilitator but also as often a negotiator between the provincial and local governments. When conducting the assessment reports and creating the plan there was a great deal of data sharing amongst the source protection authorities, creating structural networks of support. More prominently in the CSPA, as it neighbours other source protection areas, it was noted by a provincial government participant that there were effective coordination and collaboration amongst the five Eastern Ontario source protection areas/regions. The provincial government Ministries were also open in sharing data (such as between the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change and the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry). In addition, both case study regions shared SWP related data with local academic institutions and included academic representatives on their source protection committees.

Thirteen participants noted the composition of the source protection committees contributed to increasing social capacity (

Table 6). Involving a diverse range of stakeholders in the decision-making process created an environment where linkages were either created or strengthened (if existed before the process began) between municipal and provincial agencies, municipalities that shared watershed jurisdictions, community groups and other local experts such as public health liaisons. A source protection committee member explained,

“Where an issue crossed over boundaries we had a process, science based, which helped prove the data or findings to everyone, so that people could not get back into their corner of local autonomy and say well, thanks but we are going to do it this way. We were all in this thing together”.

(SPC Participant)

As represented by this quotation, a critical component of source protection committee participation was the learning and capacity building that occurred with the members around the table. Representatives had a clear idea of why decisions were being made, and would then reach out to the groups they were representing to explain the rationale behind decisions made. A great deal of time and resources were invested in educating source protection committee members (which will be discussed more in

Section 3.4). Source protection committee members noted a high commitment level to the process, despite long meetings and a great deal of homework. Decisions were based on consensus, often debating the social, economic and environmental consequences of decisions. Even if it took several meetings to reach an agreement, the process for the active exchange of ideas and viewpoints was entrenched in the CWA and its regulations.

Face-to-face interaction with committee members and other stakeholders generated trust for policy decisions. For example, in the NBMSPA the conservation authority worked with local lake associations in a tree give away program to reduce erosion and pollution in selected contributing areas. Direct engagement through source protection committee members was noted especially important for groups such as business owners and the agricultural sector. It was explained the relationship sometimes between the agricultural community and conservation authorities could be strained. It was explained, “I made some comments in the review of the conservation authority mandate to that degree. They are not seen as a friendly face in the farm community in most cases. And so they got hurdles to overcome” (SPC Participant). Traditionally, and especially with SWP matters, the agricultural community has received some blame in contaminating drinking water sources through agricultural practices such as the spreading of fertilizers. For example, in the NBMSPA there was dispute between agricultural groups and environmental non-governmental organizations on the cause of phosphorus loading in one contributing area. One risk management official said “you almost have to be a policy expert to be a farmer” (Municipal Participant). Especially since the Walkerton tragedy, the agricultural community has been highly regulated through the Nutrient Management Act, as well as many SWP policies in the source protection plans relating directly to agricultural practices. The Ontario Federation of Agriculture, the Ontario Farm Environmental Coalition and the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs did contribute to building both social capacity and technical capacity in this regard by connecting agricultural representatives across the province during additional training sessions and improving access to technical support on specific issues.

There are no First Nation communities in the CSPA. Nipissing 10 First Nation Reserve (Nipissing First Nation) is located within the NBMSPA [

31]. Though invited to the committee table, they did not participate. It was suggested by one source protection committee member that this was because the policies under the source protection plan did not impact them, and having to drive to North Bay for meetings every month would be very inconvenient. The same source protection committee member recommended that participation tools should allow for greater flexibility, such as letting participants join through web-conferencing tools.

Sixteen participants said that the CWA embedded public participation and other outreach and education in its planning process (

Table 6). This included efforts such as public consultation and open house nights, community barbeques, community round table events, shoreline restoration programs, and the use of public service announcements on the television. However, in both regions attempts to engage the public were not always well received. Ten participants indicated that better engagement techniques are required that address barriers to engagement (

Table 6). One source protection committee member explained, “…

the areas where there were no problems, it was like moving mountains to get people to attend” (SPC Participant). Generally, in the areas where there was a perceived issue with either drinking water or the impacts of the potential policies under the CWA, there were higher participation rates at public events. However, if there were no perceived issues, public engagement was limited. As all SWP efforts require ongoing actions from the public this poses a problem for the present and future implementation of SWP measures. It was mentioned by some informants that the information delivered was very technical and there was confusion around the language used. This lack of understanding made public consultations more about information sharing than meaningful consultation. One municipal participant (with expertise in environmental science) explained, “

I read the final report, but I have to go back and look at all the codes because it’s like, what the heck, it’s in latin” (Municipal Participant). These technical reports are generally not helpful for the general public. Five participants stressed that the lay summaries provided were very important for ensuring needed behavior changes were being conveyed to the public. One provincial government participant explained further about issues with public engagement,

As far as contacting the landowner and helping them understand, their attendance at all our public [events], our open houses and meetings [were] low. Which tends to translate into they don’t understand. They were contacted multiple times. Either through stewardship funding available for you know surveys and questionnaires about what we need to know, what activities are happening on your property so that we can have a good conversation with you. All the consultation on the terms of reference, the assessment report, the plan. Here are the policies that apply to you, this is what it is going to mean to you. But again until someone really shows up on your property and at that point, that’s where we as a province said we need to make sure we are supporting that. Because when they come to your door and they ask, there needs to be somebody there that can answer. And there also has to be that understanding that there is enforcement behind it should you not comply. So, yeah. We are still working through that piece.

(Provincial Participant)

Despite repeated attempts to engage the general public during the planning phase it was suggested by one provincial government staff member that engagement may increase during the implementation of the source protection plans as the public realized how exactly policies will impact them. One source protection committee member suggested in the future that there be more incentives for participation, “…there would have to be some rewards or motivation to keep people engaged and having them involved in these types of projects” (SPC Participant). Addressing barriers to engagement also has to incorporate understanding those you are trying to engage. Six participants explained that rural landowners’ sensitivity to restrictions on land use might dissuade them from working collaboratively with SWP officials or see their role in SWP.

Thirteen participants described people’s understandings of drinking water risks as “variable” in their regions (

Table 6). One participant stated that political will at the municipal level, especially in rural towns, was essential to the council’s adopting of non-binding policies outlined in the source protection plans. The tragedy in Walkerton displayed what can happen when those responsible for water systems are negligent, and the fear of repeating this tragedy was a catalyst for stricter source protection by-laws and practices at the municipal level. In addition, as previously outlined, legal ramifications for decisions concerning drinking water systems has made municipal actors more aware of drinking water issues and cognizant of the impacts of their decisions. There was evidence in both regions of rural municipalities going beyond the binding policies required in the source protection plans. However, there was still opposition of some policies from rural municipalities in both regions, usually due to fears regarding the financial cost of implementation. Conservation authority staff participants explained that any conflict or opposition of binding policies would be met with further education and outreach. Even though decisions may not have always been well received, there were venues within the process for multiple stakeholders to discuss and debate issues. This process increased communication and linkages between implementing bodies, as well as commitment to policy decisions.

Social norms and valuing of water have shifted since the Walkerton tragedy, as well as the awareness of water issues. The educational opportunities provided during the process resulted in an increase of local knowledge compared to before the CWA. For example, one conservation authority staff explained, “It was one of the best things that source protection did was to give people maps that show them where their water comes from” (CA Participant). However, as there had not been any recent drinking water incidents in both regions, it was thought that most people with municipally supplied drinking water take it for granted. As far as the effectiveness of public education and outreach efforts a conservation authority staff member explained, “...more broadly we didn’t do a lot of that necessarily in terms of advancing knowledge on a broader community” (CA Participant). Evidently, there is still work to be done. Again, as with other capacity building efforts, the plan for the future is unknown, but ongoing outreach and education is being discussed between conservation authorities and municipalities. There is some required outreach and education on certain items in the source protection plans themselves, which incorporates fact sheets, websites and children’s water festivals. However, five participants noted the unknown ongoing provincial funding for SWP implementation could constrain future outreach and education efforts. Two participants indicated that the risk management officials have played an important function in building social capacity. Part of the risk management official’s role has been explaining the reasons for certain policies to those impacted by implementation. These types of methods have increased knowledge at the local level, as well as have contributed to slowly shifting social norms.

3.4. Technical/Human

Technical/human capacity refers to the physical and operational ability of an organization to perform SWP management and operations adequately. This also incorporates having human resources, with adequate knowledge, skills and experience to properly create source protection plans and implement needed measures [

12,

20]. In total, 27/30 informants spoke about technical/human capacity in their interview. Again, similar to the other facets of capacity for SWP the CWA built technical/human capacity in the case study regions (

Table 2). Seventeen participants noted the development of technical capacity at the municipal level. This increase in technical capacity was attributed to technical aid from the conservation authorities and Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change liaisons (who sat on source protection committees) (

Table 7). Funding from the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change raised technical/human capacity at the conservation authority level. The conservation authorities were integral in providing staff with technical expertise that facilitated the process and who physically wrote the source protection plans. Particularly for rural municipalities, conservation authorities provided much needed support in all facets of the process, including implementation. One municipal staff member explained,

“The North Bay-Mattawa Conservation Authority kind of spearheaded the whole thing. Basically, I believe we got funding, and then we just basically gave them the funding. And then they hired a consultant to take care of the official plan and zoning bylaw amendments”.

(Municipal Participant)

A conservation authority staff member explained, “

I think the local decision makers have enough support that even if they don’t have a deep understanding themselves they’ve got the resources at their finger tips and we are always a phone call away too” (CA Participant). Eighteen participants noted that the process under the CWA has increased human capacity both at the conservation authority level, and in some cases at the municipal level with funding for risk management officials (

Table 7). Some smaller municipalities have deferred their risk management responsibilities to the conservation authority. What is of concern is the ongoing support for staff members at the conservation authority. One criticism of the CWA, expressed by one source protection committee member, was that it was legislation to make a product (the source protection plan) and there has not been enough attention to sustaining, particularly, the conservation authorities’ role. One source protection committee member explained,

“Conservation authorities are getting tired. They have no more fiscal and internal capacity to devote to this. They’ve got to be satisfied that there is a sustainable flow of resources to allow them to continue to do this in a partnership. They can’t keep doing this just because it is good for you. Conservation authorities’ resources are limited and stretched, and they often beg for help from other authorities. And that is why the argument is that senior levels of government have got to get behind this”.

(SPC Participant)

Though this statement relates to financial capacity constraints as well, the decrease in provincial funding has resulted in decreased technical staff at the conservation authorities. As mentioned previously some conservation authorities noted keeping staff on to work on other projects, however this could not be done for all staff. Even if more funding was available in further planning and implementation efforts, important institutional knowledge has now been lost, as those original staff members have gone on to different organizations. One source protection committee member noted it will be more difficult for conservation authorities such as the North Bay-Mattawa Conservation Authority, who are smaller and do not have staff at near by conservation authorities to collaborate with.

Learning opportunities and the building of technical capacity during the planning process was high. As previously explained there was a significant amount of technical training devoted to the source protection committee members. Fourteen participants noted technical capacity being raised for those on the source protection committees via educational resources, presentations and co-learning (

Table 7). Furthermore, working groups were created during the planning process. These working groups included source protection committee members as well as additional municipal representatives and others who would be eventually impacted by policy decisions. Presentations on certain topics of interest were also given at the source protection committee meetings as well as the working group meetings. Varied skillsets and expertise (academics, environmental lawyers, activists, etc.) allowed source protection committee members to learn from each other. However, it was noted that committee members could be overwhelmed by the amount of technical information that they were required to absorb. A conservation authority staff member explained, “even technical staff were challenged with the amount of information we had to go through” (CA Participant). Agricultural representatives were provided with additional training and support by the Ontario Farm Environmental Coalition, Ontario Federation of Agriculture, and Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs. Three participants noted this additional aid to agricultural representatives as beneficial. For example, in the NBMSPA there was a technical dispute related to a potential agricultural threat where the Ontario Farm Environmental Coalition provided data and expertise in support of their agricultural representative. Furthermore, the function of the Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change liaison was noted by two participants as important in providing technical capacity to source protection committees, as well as creating a link to other provincial ministries such as the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, and the Ministry of Transportation.

The process under the CWA was effective for educating municipalities, and getting them prepared for their role in implementation. However, more ongoing education needs to be in place. Ten informants noted municipal staff and elected official’s understandings of the need for SWP could be a potential barrier to implementation (

Table 7). This is especially the case if re-education of municipal staff and elected officials does not occur in the future. Three participants indicated, due to the nature of the four-year cycle of elected government, it has to be an ongoing effort to ensure municipal actors understand the reasons for these policies. A source protection committee member explained,

“You cannot make assumptions about the capacity and expertise and knowledge of individual municipalities as a static, as a given. Municipalities come in all different sizes, over time people retire, people move on, elected officials move on. New people come in and we don’t know what their backgrounds are. So, there will be this constant rebuilding of knowledge and history as people move out and new people take their place. Elected, administrative, and even in the communities themselves”.

(SPC Participant)

Municipalities, especially smaller ones, lacking internal expertise, may not always understand the science behind the source protection plan and related policies. However, 20 participants agreed municipalities do understand their role in implementation (see

Section 3.1). The ongoing re-education of newly elected officials and municipal staff is critical. Notably, the risk management officials, who enforce policies under the source protection plans, have gone through significant training. Risk management officials (often municipal employees but sometimes this role has been deferred to the conservation authority) continue to work with consultants and provincial staff in interpreting guidelines. The risk management official also serves as an interpreter to municipal staff and elected officials in SWP under the CWA.

In regard to access to adequate data for SWP, data gathered for the assessment reports have derived important baseline information for the regions involved, and this has been an important benefit of the planning process. It was noted by 24 participants that the data created and shared during the creation of the assessment reports, increased technical capacity, especially for rural municipalities (

Table 7). There are now studies to inform decisions. Though, as mentioned, data sharing was effective between provincial ministries, two participants noted that structures are needed for more formal and strategic data sharing in regard to source water supplies. Increased staff at the conservation authority level would also be needed to implement a collaborative data-sharing program. Technical guidelines that contributed to the making of policies in the source protection plans, such as the Tables of Drinking Water Threats and guidelines for how to assess vulnerability and classify intakes and wells, were valuable for creating consistent, transparent and technically defensible policies. However, 10 participants noted issues with the technical guidelines (e.g., Tables of Drinking Water Threats, vulnerability ratings, and capture zone delineations) (

Table 7). The prescriptive nature of the technical guidelines sometimes made it hard to apply to local circumstance. Both case study regions wanted to expand beyond the prescribed list of threats in areas such as threats for Lake Ontario intakes, threats related to clusters of private drinking water wells, and threats related to pipelines. There were also noted limitations by seven participants regarding the rigidness of capture zone delineations based on groundwater model simulations. A consultant involved in the process explained,

“the concern lies in how much faith we put into the results of the model. Models can create lines on a map that non-modellers will adopt as fact and may then create real world rules (i.e., planning decisions) based on the position of a line (a time of travel capture zone) that itself is only a generalization, and quite possibly an educated guess at best”.

(Other Participant)

One risk management official explained that some consultants conducting modelling for the assessment reports were not aware of how models would be used in the whole process. It is clear throughout the planning process, the focus was on intake protection zones, versus watershed protection. One source protection committee member explains,

“The only thing, [a] limitation would be the fact that the reports, after you did the characterization report, everything started to focus only on drinking water intake zones, which really rammed us back to prior to the Clean Water Act. I mean we have always been looking at intake zones, so, we haven’t really moved into a watershed [plan]”.

(SPC Participant)

In the end, though this first round of planning was essential for building technical capacity for SWP, it did not always allow for all locally specific issues to be addressed. Therefore, there is need for further evaluations of threats. For example, one area of concern expressed by 10 participants in regard to future threats to be evaluated was the impact of climate change on source water supplies. Conservation authorities are tasked in annual reviews and creating new work plans, and can apply to the Minister for further inquiry into specific topics of interest. There is a need to keep the science and policies in the source protection plans up to date. Seven participants indicated that as provincial funding declines to the source protection program so does the maintenance of the built technical/human capacity (

Table 7). SWP cannot succeed if plans are stagnant. Technical and human capacity to undertake technical studies must be maintained to adequately protect source water supplies now and into the future.