Abstract

The European Union (EU) is globally the second highest emitter of greenhouse gases from drained peatlands. On the national level, 15% of agricultural peat soils in the Netherlands are responsible for 34% of agricultural emissions. Crucial to any successful policy is a better understanding of the behavioral change it will bring about among the target groups. Thus, we aim to explore farmers’ differing viewpoints to discuss how policy and planning can be improved to ensure landscape-scale climate mitigation on agriculturally used peatlands. Q methodology was used to interview fifteen farmers on Dutch peat soils, whereby 37 statements were ranked in a grid according to their level of agreement. Factor analysis revealed three main viewpoints: farmers with a higher peat proportion show an urgency in continuing to use their land (‘cooperative businesspeople’), while ‘independent opportunists’ are wary of cooperation compromising their sense of autonomy. Farmers who are ‘conditional land stewards’ are open to agriculture without drainage but require appropriate payments to do so. Future policy design must focus on providing support to farmers that go beyond compensation payments by providing information about funding sources as well as potential business models for peatland uses with raised water tables.

1. Introduction

The European Union (EU) is responsible for 15% of total global emissions from drained peatlands, making it the worldwide second highest emitter of greenhouse gases (GHG) from peatlands [1]. The EU has committed to attain the main goal of the Paris Agreement which set zero net carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by 2050, and therefore GHG mitigation on peatlands has an important role to play in Europe’s climate policies.

In the Netherlands, peatlands are not viewed as marginal lands; the flat grazing meadows intersected by many ditches are a classical feature of the Dutch landscape. Peat soils cover 290,000 ha (approximately 8% of the land area) of which 82% is used for dairy farming, with water levels typically between 30 and 70 cm below ground [2]. To make the peat suitable for typical agricultural practices such as grazing meadows, a network of artificial water-drainage catchments known as ‘polders’ were created, dating back to the Middle Ages [3,4].

Intensive agricultural use and associated drainage causes peat soils to shrink and over the centuries this has driven major land subsidence in the Netherlands between two to four metres [5]. Another consequence of artificially lowering the water table on peatlands is CO2 release, as organic material is mineralized as it comes into contact with oxygen [6]. Furthermore, as the water table lowers or draining intensity increases, so does the intensity of emissions [7]. Thus, 34% of agricultural emissions in the Netherlands come from drained peatlands [1] making it one of the largest national emitters worldwide [8]. There has been recognition that continued drainage will incur great costs for spatial planning in the future, for the building and water management as well as the agricultural sector [3,6,9]. Moreover, recent research has warned that substantial welfare loss may be associated with delayed peatland restoration [10].

To mitigate GHG emissions on peatlands and to reduce subsidence, it is necessary to halt drainage on farmland with peat soils, which implies raising the water table. In the EU, various measures for GHG mitigation from agriculture have been identified, such as cultivation of wetland crops (“paludiculture”: 7) and raised ditch water levels [11]. Measures such as subsoil irrigation have been promoted in the Netherlands. However recent research suggests that changes to the water table within the first 60 cm of peat soil is insufficient to reduce carbon emissions at the field level [12]. Such measures demonstrate the trade-off between climate mitigating action on peatland and conventional agriculture management. A key challenge lies in creating options which are sustainable. This means preventing further carbon loss but also giving farmers a profitable opportunity to continue using their land [9,13,14].

For peatlands in particular, this means that a water table must be managed in contiguous areas to make a noticeable impact on the hydrological network [14,15,16,17,18]. This is referred to as a landscape-scale or an ecosystem-approach to peat management [19,20,21]. To warrant such landscape-scale peatland management, agri-environment-climate measures (AECMs) need to support cross-farm cooperation [22,23,24,25].

Crucial to any successful policy is a better understanding of the behavioral change it will bring about among the target groups. In the case of voluntary financial incentives, such as collective AECMs, it is therefore important to understand farmers’ motives for cooperating with each other. The most effective way to incorporate these motives, so that they drive the raising of the mean water level on used peatlands, is if they are taken into account in the concrete design and implementation stages of voluntary AECMs.

Long-term drainage of interconnected peat sites can cause disturbances in (eco)hydrology, affecting extensive hydrological networks, with changes reported several hundred meters away from the location of drainage [26]. In addition to slowing down soil subsidence and reducing GHG emissions [9], coordinating efforts between individual farm businesses to raise the mean water level across an extensive peat area can directly and indirectly improve ecosystem services across a landscape, such as species diversity [17] and water quality [15].

Since farmland is often fragmented, such ecosystem services can only be achieved if farmers and landowners are able to manage and implement AECMs together [24]. In contrast to other AECMs, raising the water level often requires a change in business or management style for the farmer, therefore suitable compensation schemes and new management models on agricultural peat soils must support such a transition [23]. One important question for policy design remains: what motivates farmers to cooperate?

We conducted interviews with farmers on peat soils who are members of regional agri-environment associations to understand what motives and expectations they have as part of these cooperative structures. If farmers should agree to raise the water table, it is important that scientists and policy makers understand farmers’ perspectives and include them in the design and planning process [20,27]. Nevertheless, to the knowledge of the authors, no studies exist which explore farmer’s motivations to participate in cooperative agri-environmental management specifically in the context of raising the water table on peatlands. The closest study found to address this issue was that of Haefner and Piorr [20], which investigates peat farmers’ views towards coordinating institutions in Germany using discrete choice experiments.

How farmers perceive cooperation is crucial for environmental measures to be successful at the landscape-scale [14]. This paper seeks to fill this gap by discussing the following questions:

- How do motivational profiles to engage in cooperative peatland management differ between farmers?

- How can these viewpoints be integrated by decision makers at various levels?

To reveal these viewpoints we used Q methodology, wherein farmers were asked to rank a series of statements that reflected three main motivational categories: costs and benefits, personal norms, and social norms. Hence, we discuss the research questions based on farmers’ responses to the statements.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study

The Netherlands has a long history with cooperative structures, from labor and producer cooperatives to agri-environment collectives [25,27,28]. Since 2016, the Netherlands is the only country in the EU to implement AECMs through collective organizations [29]. For clarity, when we use the term “collective” we refer to the regional agri-environment associations in the Netherlands, while the terms “cooperation” or “cooperative” in this study are used to describe the management principles of these collectives, or of a landscape-scale approach. The collectives act as a “bridging organization” between farmers and the government [30].

There are 40 collectives across the country, all regionally certified associations which steer the implementation of AECMs of their members, including farmers and land managers [31]. For the AECMs, the collectives receive government payments for contractual conservation targets which they redistribute by concluding private contracts with individual land users that define activities at field level [29]. The coordination activities of fine-tuning individual contracts according to the habitat’s requirements at landscape-scale, next to facilitating knowledge building, are carried out by employees of the collectives.

2.2. Data and Methods

Q methodology (hereafter: Q) is an explorative research approach which asks participants to rank and relate various predefined opinion statements in a grid according to their level of agreement. Participants with similar grid rankings (Q-sorts) cluster into so-called “factors” [32], also referred to as “typologies” (e.g., [33]), “narratives” (e.g., [34]), or “discourses” (e.g., [35]). In contrast to other conventional statistical approaches (“R”-based methods), the variables in the interview are the participants themselves [36].

Q is particularly suitable to peat management on farmland since many of the sustainable management options proposed so far are currently in pilot phases and are, in most cases, not yet viewed as “ready for practice” [37]. Q in this study seeks to understand the pattern of views and cooperative motives of farmers on peatlands, to advance future landscape and policy planning [32,35].

2.2.1. Statement Development (Q-Set)

To guide the development of the structured statement set, or Q-set, in relation to the research question, we used a framework from Barghusen et al. [38] which encompasses farmers’ diverse motivations to participate in collective AECMs. Barghusen et al. based the framework on a handbook for environmental psychology by Hamann et al. [39] and a literature review on motivation-related aspects of farmers in collective conservation situations, and successfully applied it in a workshop and survey with representatives from Dutch collectives. It presents three main categories of motivation, subdivided into eight further categories (Appendix A, Table A1).

We reduced the number of statements to strictly focus on the main strands of the trade-off between climate mitigation and conventional peatland management. Watts and Stenner [36] emphasize that the size of the Q-set should not be overwhelming for the participant but should also not compromise the breadth of the “opinion domain” around the main research question. We found 37 statements to be sufficient to cover the current discourse surrounding this study’s research questions as well represent each motivational category, which also conveniently corresponded to a typical Q-set size [40]. After a pilot interview and feedback from three collective employees, the statement list was sent to the Dutch interviewer to be translated from English.

2.2.2. Participant Selection (P-set)

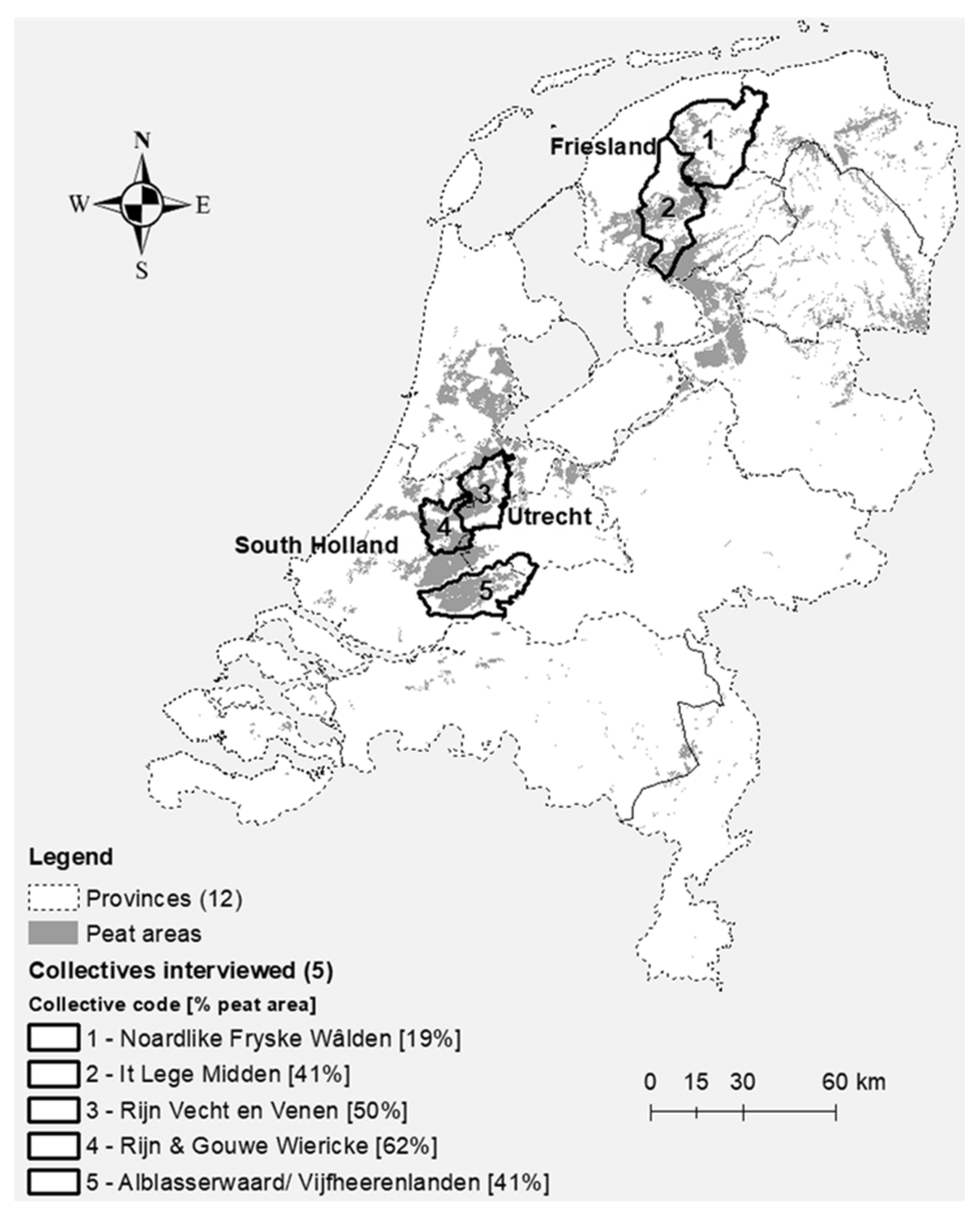

We used convenience sampling [32] and contacted BoerenNatuur, the collectives’ umbrella organization, for finding Dutch participants for the interviews based on two criteria: they must be (i) a farmer on peat soils, and (ii) a current member of an agri-environment collective. A final P-set of fifteen farmers from five different collectives voluntarily responded to our request (Figure 1) which satisfied the participant:statement ratio (1:3) according to Grimsrud et al. [34].

Figure 1.

Map of Dutch peat areas overlain by regions of the five collectives interviewed in this study. (Map creation: author’s own, using ArcMap [ESRI]. Geospatial data sources: BoerenNatuur [collective areas], GADM [administrative boundaries]) and Wageningen University and Research [peat soil areas]).

2.2.3. Interview and Analysis Process

After formal consent from each participant was obtained, all fifteen interviews were conducted between November and December 2020, in Dutch. Each Q interview lasted between 25 and 45 min and was held online using video call and the tool “Aproxima htmlQ” (https://github.com/aproxima/htmlq, accessed on 20 September 2020).

Before beginning, the interviewer stressed that the statement ranking was not a test of knowledge and was rather a study to understand perspectives about peatland management [41]. The categories of motivation were not revealed to the participants, to minimize interpretation bias.

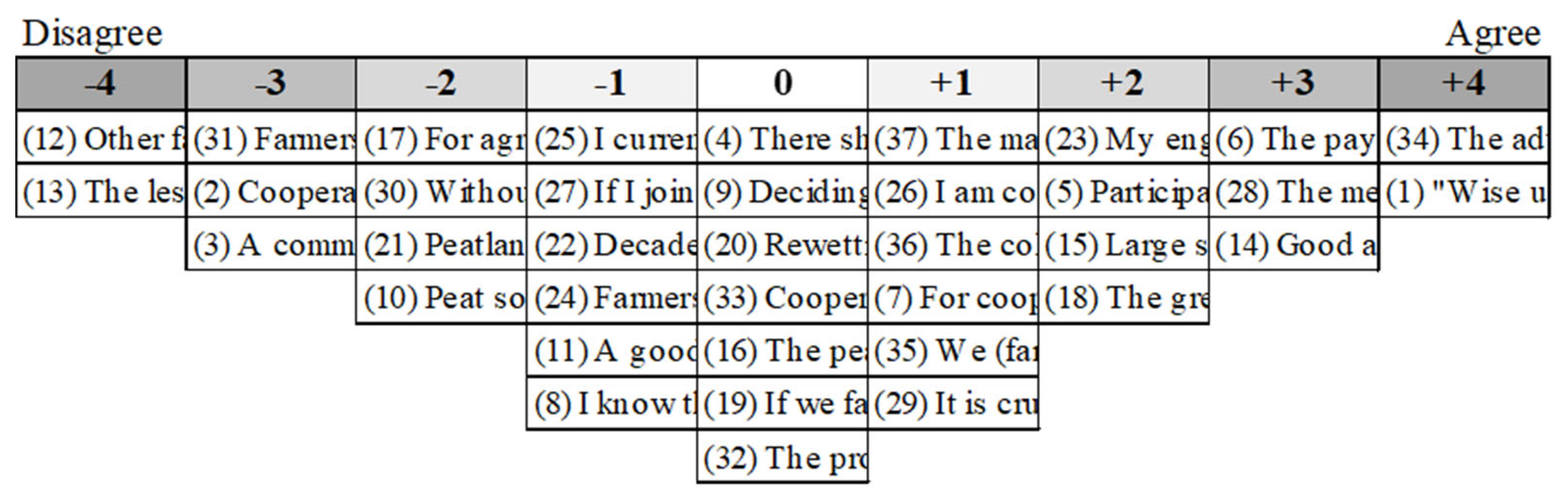

The Q grid contained 37 boxes, representing a forced-choice distribution (Appendix B, Figure A1; [35]). In the first step of the sorting, participants were asked to separate statements into three piles (disagree, neutral, agree). In step two they were presented with the Q grid, where they were asked to sort statements from the piles, from −4 (most disagree) to +4 (most agree).

The Q-sorts (final statements rankings based on their placement in the Q grid) from each of the fifteen participants were arranged in columns and analyzed using the freely downloadable qmethod package (accessed on 3 October 2020) designed for use in R applications [42]. This package uses a forced distribution as a standard precondition, principal components analysis (PCA) to extract factors and varimax factor rotation. Consensus and distinguishing statements, based on differences between z-scores, were marked up and compared between factors.

Interview quotes, feedback sessions with the interviewer, as well as multiple review processes were used to interpret and qualitatively describe the resulting factors. Prior to the Q interview, a questionnaire containing fifteen closed questions was sent to each participating farmer to obtain information about their farming background and farm characteristics which would assist in the factor interpretation. Finally, we drew links between the factor narratives and their relevance at various decision-making levels.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Factor Characteristics

On summarizing each of the fifteen farmer Q-sorts, all statistical criteria were fulfilled when three factors were extracted (Table 1). Two individuals’ Q-sorts did not load into a single factor, indicating that these participants’ opinions were split between two or more viewpoints [43]. These two Q-sorts were therefore excluded from further analysis (Supplementary Material Excel S2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of rotated and extracted factors.

Farmers in F1 display the smallest average proportion of income from farming while F3 representatives have the highest relative income. Moreover, F1 farmers hold the highest proportion of peat area in relation to their farm size. F1 and F2 representatives farm more intensively on their land compared to F3 farmers.

3.2. Factor Narratives

3.2.1. Consensus

The Q analysis identified seven statements of consensus, meaning that opinions about these statements are similar for all factors (Table 2). All factors strongly agreed that environmentally friendly farming must be remunerated (S31, ~+4) and that cross-farm activity can reduce land subsidence (S15, ~+3). Similarly, there is unanimous disagreement that farmer-to-farmer communication is irrelevant to the success of an AECM (S13, ~−3).

Table 2.

Factor scores and z-scores per statement, sorted by motivational subcategory.

3.2.2. Distinguishes All

Factors show distinctly differing views about the indirect rewards associated with peat protection and long-term soil fertility (S32). While F2 farmers neither agree nor disagree with the statement (0), F1 agrees (+2) that protecting peat will maintain soil fertility. F3, however, shows a relatively high level of disagreement with this statement (−2). One farmer in this profile group explained that the meaning of soil fertility may be understood differently depending on the site.

Nor is there a shared perspective about lead farmers during a cooperative activity (S29). F1 is ambivalent about this statement (0) while F3 sees some value in having a lead farmer (+1). F2, however, ranks this as one of the most important statements in the Q-set (+4).

3.2.3. Factor 1–Cooperative Businesspeople

This profile of farmers clearly puts agriculture before climate. Climatic benefits of rewetting are less convincing as an argument for peat protection for these farmers (S20, −2). Their priority is to continue to farm their land, but they cannot imagine how “good agriculture” can continue without drainage (S14, +3; S17, +4). They would like to see payments for agri-environmental measures that go beyond compensation mechanisms (S6, +4):

“I think there should be a way to earn money behind [the measure]. We would not get it from the milk, so extra efforts have to be compensated.”(Farmer 4)

“If you want to move farmers in a certain direction, then the tactic of tempting should be applied. There must be a bonus or business model, not only a compensation when doing extra work.”(Farmer 9)

Despite putting agriculture first, F1 farmers are also more likely to implement peat soil conservation regardless of whether there is a payment (S30, −2). This may be related to their relatively modest view of themselves as land stewards (S24, −1) and their appreciation of the administrative benefits of collective action (S36, +1).

In comparison with the other factors, F1 farmers place greater value on working together (S12, −1; S19, +3). They would like to see more cross-sectoral support as they are strongly against the notion that they are the sole actors responsible for peatland protection (S37, −3): “Emissions are not only done by farmers, so cannot only be solved by the farmers.” (Farmer 9). They are less sure than other factors about whether society appreciates the work of the collectives (S8, 0) but strongly believe that farmers working together can provide a positive public image (S19, +3).

3.2.4. Factor 2–Independent Opportunists

Like F1, F2 farmers value their occupations as farmers on peat soils over climate protection. Compared to the other two groups of farmers, F2 farmers show a more urgent need to address peat soil subsidence for the sake of their (farming) livelihoods (S10, −4).

Money plays an important role for these farmers (S30, +2; S31, +4) but they also value intrinsic rewards related to independent work (S11, +1). They believe that their own agri-environmental activities can lead other farmers to implement similar measures (S28, +3; S29, +4). Strikingly, F2 farmers have a distinct opinion about the benefits of cooperation (S2, 0). They see other farmers less as cooperators than the other factors (S12, −2):

“There is less land available to farm, so in the end we are competitors. But farmers are also neighbors which help each other. You do not want to see it like that, but it is like that of course.”(Farmer 14)

These farmers have a strong opinion that it is outside of the farmer’s responsibility (S37, −3) and beyond the collective’s duty to act against peat soil subsidence (S26, −2):

“[acting against subsidence] is no task of the collective. The water authority and the province are closer to the problem: one organization is concerned about the wet area, the other about the land. I think they are linked. I talked about this several times, but nobody listens.”(Farmer 1)

F2 farmers do not view the public as a force of motivation (S19, 0; S25, −1) but believe that the actions of the collectives can be appreciated by the public (S8, +2).

3.2.5. Factor 3–Conditional Land Stewards

In contrast to the other viewpoints, such farmers dissociate strongly from the notion that farmers are only agricultural producers (S24, −4). They are less of the opinion that peat soils should continue to be farmed by current means: they can imagine pursuing ‘good’ agricultural practices even without drainage (S14, −2), they are less inclined to believe that agriculture needs drainage (S17, −2) and they agree that there can be climatic benefits from raising the water table (S20, +2). These farmers have a proportionally small peat area compared to F1 and F2 averages. However, they also have the highest income from farming (Table 1) which may partially explain the strong expectation that payments should reflect the degree of rewetting (S18, +4).

While cooperation may not be easy due to a heterogeneity of land uses (S9, +3), F3 farmers largely agree with those in F1 that working together is important (S2, −3; S12, −4; S35, +1). They believe more than the other factors that farmers have a responsibility to protect peatlands (S27, −1). However, they are not very persuaded that nature protection and productive yields from agriculture can coexist on peatlands (S1, −1):

“I do not see the balance very well: it is the one or the other. If I see that the land gives lower quality grass, when we take place in meadow bird management.”(Farmer 3)

Like F2, F3 farmers are not driven by the public’s perception of farmers’ actions (S25, −2); instead, they show some confidence that farmers working in cooperation as well as the work of the collectives can do more in receiving societal appreciation (S8, +1; S19, +1).

4. Discussion

Our findings aim to encourage acknowledgement of different peat management motivations by and between farmers, since this can play a key role in the design and communication of suitable AECM applications. Having a representative number of distinguishing profiles or viewpoints of farmers can create new perspectives for policy plans. A significant setback of Q is that there is no standardized protocol concerning how to interpret the viewpoints revealed by the quantitative analysis, much like assemblage theory [44]. While this analysis reveals three significant farmer viewpoints, it is also possible that within these viewpoints multiple minor perspectives are integrated [35]. The main focus of this study is to suggest communication approaches which specifically target different farmer profiles. The three overarching viewpoints therefore frame a communication basis on which to build on and develop new policies.

4.1. Motivation to Cooperate

Our results show that most farmers have a positive view towards cooperation. This contrasts to results from Germany, where Haefner and Piorr [20] found that farmers in Germany who had more professional training show less favorable attitudes towards cooperation. Dutch farmers in this study do not follow this pattern of thought, which is likely due to the long history of cooperative structures in the Netherlands. More recently, political pressures such as the nitrogen crisis in 2019 have united farmers and given rise to organizations such as the ‘Farmers Defence Force’. Farmers have thus had considerable time to become accustomed to and trust the benefits of cooperation [25].

Interestingly, a farmer’s region and collective membership does not allude to the viewpoint (F1, F2, or F3) they hold, indicating that the cooperative approach for landscape-scale management may be a common locus of intervention for discussing sustainable peatland options with farmers, regardless of the region. This coincides with other studies’ findings, that farming styles are “not entirely” region-specific [45] and that differences in willingness to cooperate cannot be attributed solely to farm location [27].

In the context of peatlands, our results suggest that it is rather the share of peat soils and livestock density that determine the cooperative viewpoints of a farmer. If we assume that a farmer’s peat proportion and livestock density are proxies of dependency on peatland, our results suggest that a farmer’s motivation to cooperate in peatland protection is negatively related to dependency on peatland, as illustrated by the cooperative businesspeople’s (F1) viewpoint in contrast to that of the conditional land stewards’ (F3).

Burton et al. [46] and Thomas et al. [47] find that a farmer not only considers financial gains and losses when changing a farming activity, but also associated costs to social and cultural capital. Our study similarly shows that a farmer whose business is more dependent on peatland feels that they have more ‘face’ to lose, in other words higher opportunity costs related to social and cultural capital, if they take part in cooperative measures since they expect more pressure and consequently must put in more effort to change their practices [48]. To minimize these costs, a focus should be placed on providing advisory support to such farmers, together with and from other local stakeholders in these peat areas, especially since these relatively peat-dense farmlands are areas of higher environmental value [49].

On the other hand, farmers on less-dense peat area and whose income mainly comes from agriculture (independent opportunists, F2, and conditional land stewards) may place a greater emphasis on financial capital and appear to be more motivated by economic support for conservation action [19,48,50].

It is important to note that cooperation may not contradict individual autonomy, as is the case for independent opportunists, so long as the final decision-making power stays with the farmer [51]. There are limits in willingness to cooperate: if a farmer agrees to cooperate in a large-scale peatland protection measure, they may want to define which activities contribute to this themselves [25]. Policies which are open and flexible regarding the array of activities which can contribute to a conservation goal, and that tolerate changes in perspectives over time, may therefore be more motivating for farmers to cooperate in AECMs [21,24,52].

4.2. Viewpoint-Specific Suggestions for Approaching Farmers in Collectives

This brings the discussion to the role of the collectives. Coordinators for sustainable peatland management projects within the collectives can use the results from the motivational profiles to plan future AECM applications, or to inform their current communication approaches with farmers on peat soils.

Spatial connectivity between farm sites is one major issue that is consistently raised in the discussion about landscape-scale AECMs [25]. Our results highlight the importance for the collectives to know which farmers are more dependent on peat soils than others so that projects and communication strategies can be adjusted accordingly.

For farmers who are independent opportunists to engage in cooperative action, it is especially important to have projects which are flexible and allow for management decisions which have a higher degree of independence from neighboring farmers. For such farmers, working closely with others is rather seen as a burden. Therefore, contracts with other collective members would not appeal to them as much. Organized visits to demonstration sites for paludiculture may be an important point of persuasion for independent opportunists to engage in sustainable peatland management [7]. Ziegler et al. [53] state that since biomass from paludiculture cannot compete with yields from conventional peatland use, stakeholders must be included at the beginning of the planning process and receive “sustained policy support” to make “wet” agriculture on peat soils feasible.

The framing of sustainable peatland management through meadow bird protection programs and land subsidence is widespread in the Netherlands [54]. However, this strategy may be too narrow for farmers who see themselves as conditional land stewards since it does not directly address the climatic effects of peat drainage. Including diverse framings which are based on sound scientific evidence and cultural values may be useful in attracting a wider audience of farmers to participate in cooperative AECMs, as well as highlighting the long-term climatic implications of peat oxidation and fertility loss through drainage.

Moreover, especially for independent opportunists, membership or engagement of non-farmers in the collectives (if not already present) could be beneficial for encouraging cross-sectoral relations and exchange [14].

4.3. Recommendations for Policy

One important question is how to foster landscape-scale management of peatlands within agri-environmental policies? We want to use our results to discuss this question.

Although climate protection has become an important goal in the field of agri-environment or agri-investment programs in Europe, few targeted measures for peatland protection are included in these [7]. Beside the fact that many management options for peatland protection need to be adopted at the landscape-scale, there is also the issue that the carbon emissions cannot be effectively monitored on individual peat sites [19], which suggests that peatland protection cannot be adequately managed through contracts with individual farmers. Therefore, the experiences in the Netherlands that farmers are willing to cooperate are interesting. Governments in other countries could follow the Dutch example to incentivize cooperation by giving priority to joint applications for peatland related AECMs over individual ones (cf. [14]).

Collective employees have shown that they believe direct monetary rewards to be one of the most important motivations for farmers to engage in AECMs [38]. Our results confirm the assessment of the collectives, but unless farmers are presented with feasible business models for changing their peatland use, sufficient financial allocations remain a cornerstone for measures in the field of (cooperative) peatland management. National governments or regional collectives could motivate farmers by offering a ‘Funding Handbook for Carbon Farming’ for peat farmers, with information about market access, existing funding support and eligibility requirements related to land management with a raised water table. During the last years different public and private initiatives have started to promote peatland restoration (e.g., IUCN Peatland Program in the UK) and develop markets for buying carbon certificates for rewetted peat sites (e.g., MoorFutures in Germany, and Valuta voor Veen [Paying for peat] in the Netherlands).

Market access is a key concern for farmers’ and consumers’ acceptability of products from peatlands with a raised water table [19]. If special priority is given to home-grown products from peatlands, such as Common Reed as a construction material from paludiculture, this may motivate farmers to consider cooperating in the adoption of these practices. Another policy instrument which can reward a change in management is labelling [38,55], as has been carried out for milk from meadow bird protection sites (labelled as ‘weidevogelmelk’, not only specific to peat-based grasslands). Still, consumer acceptance, trust and habit also play a crucial part in the acceptance of new market products [39], therefore public outreach at regional and national levels must complement such policies.

Globally, payments for ecosystem services could be one instrument (beside others) to reduce carbon emissions from agriculturally used peatlands. However, new cooperative schemes are important, by way of agglomeration bonuses for example [38,56], to foster necessary collaboration between farmers to achieve landscape-scale environmental impacts.

4.4. Future Research

Although this study is not intended to be representative of all Dutch peat farmers, we propose that the viewpoints identified from the Q analysis provide a first insight that farmers are not averse to landscape-scale policy making. Since the interpretation of the profiles was mainly conducted by authors with a scientific background, we encourage the wider Dutch farming community, particularly the collectives, to use these three motivational profiles as a contextual setting for an open discussion or workshop with farmers and other relevant peatland actors (e.g., [57]).

Farmers need to be presented with options and know-how if they are expected to continue their business with a raised water table. New business models, which give advice on relevant funding opportunities and policy support according to the changed land use, must be developed and made available to farmers [7,19].

Further research with farmers and other actors in peat-dense countries must be carried out to investigate the relationship between a farmer’s peat proportion and motivation to cooperate in protective peatland management, as hinted by the differences between cooperative businesspeople and conditional land stewards. Finding intersections between stakeholders and their perspectives may be key to creating landscape-scale climate mitigation strategies on peatlands which are resilient [58].

5. Conclusions

There is great value in understanding different perspectives for enabling cooperative peatland management, and this study has presented several motivations from the farmers’ point of view. Three main profiles of motivation were found, and the results show that further study should examine the connection between on-farm peat proportion and motivation to cooperate.

Other countries or regions may adapt the study method to interview farmers or other stakeholders on peatland, to foster critical self-reflection about cooperative approaches across the peat landscape. If the public expects GHG mitigation measures on peat soils to assist in reaching the 2050 climate neutrality target, our results show that there is a need for credible, long-lasting revenue models which can illustrate to farmers the financial feasibility of land management with a raised water table.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/land10121326/s1. Code S1: R code for Q method; Excel S1: Q input data for R; Excel S2: Q results interpretation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.N., B.M. and R.B.; methodology, J.N., B.M., R.B. and C.S.; validation, J.N., B.M., R.B. and C.S.; formal analysis, J.N. and C.S.; investigation, B.v.G.; resources, J.N., B.M., R.B., C.S. and B.v.G.; data curation, J.N. and C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, J.N. and B.M.; writing—review and editing, J.N., B.M., R.B., C.S. and B.v.G.; supervision, J.N. and B.M; funding acquisition, B.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was made possible in part through funding by the PEATWISE project under the FACCE ERA-GAS Research Programme (under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research & Innovation Programme, grant agreement No 696356).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

In accordance with ethical guidelines and good scientific practice, we obtained consent from participants of our survey and workshop in the following way: For both the brief written and online surveys, we included a declaration of consent and informed respondents about confidential data usage, the purpose of the survey, and a contact address in case of questions and remarks. For the workshop, we also explained the aim, provided contact addresses, and orally asked for consent to record the discussion beforehand. All collected data was anonymized to ensure privacy. The original data is and will be stored on a secured server at the Leibniz Centre for Agricultural Landscape Research (ZALF) until it is deleted according to the Centre’s data policy regulations.

Data Availability Statement

BoerenNatuur has ownership of geospatial data of the collectives’ regions, which we were kindly allowed to use in relation to this study. The remaining data is primarily contained within the article or in the supplementary material. Other data is available on request and is stored on a secured server at the Leibniz Centre for Agricultural Landscape Research (ZALF) until it is deleted according to the Centre’s data policy regulations. BoerenNatuur has ownership of the geospatial data of the collectives’ regions which we were permitted to use for this study.

Acknowledgments

Our thanks go to the staff at BoerenNatuur for allowing access to geospatial data of the collectives’ regions. We would like to thank the five collective employees who helped us find fifteen farmers on peatland to interview, and particularly to the three employees who provided valuable feedback and comments during the study design. We would also like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their perceptive comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest or financial ties to disclose.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Categories of farmers’ motivation from [38], for participation in cooperative AECMs and corresponding Q statements.

Table A1.

Categories of farmers’ motivation from [38], for participation in cooperative AECMs and corresponding Q statements.

| Motivational Category | Subcategory | Statement Number | Q Statements | Source(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. Costs and benefits | a1. Direct monetary rewards | 4 | There should be a bonus payment if all relevant farmers participate in rewetting. | [56] |

| 6 | The payment should be higher than the opportunity costs. | [49] | ||

| 18 | The greater the water level raise, the greater should be the payment. | [4] | ||

| 30 | Without payments I would not implement peat soil conservation. | [20] | ||

| 31 | Farmers have to be paid for environmentally friendly land use. | [30,52] | ||

| a2. Indirect rewards | 5 | Participation in the collective increases my personal farming knowledge. | [31] | |

| 20 | Rewetting contributes to the stabilization of the water table during extremely dry summers. | [3] | ||

| 32 | The protection of peat soils ensures that soil fertility is maintained in the long term. | [9] | ||

| 33 | Cooperation through my collective can also be used for the joint marketing of products. | [14] | ||

| 34 | The advice from the collectives is helpful for my business. | [14,29] | ||

| a3. Cost savings | 35 | We can save costs through division of labour and shared machine use. | [52] | |

| 36 | The collective helps us to reduce administrative costs. | [52] | ||

| b. Personal norms | b1. Problem awareness | 1 | “Wise use” of peatlands means finding a balance between nature protection and providing agricultural products. | [59] |

| 10 | Peat soil subsidence is not relevant for my business | [3,4,5] | ||

| 17 | For agricultural purposes, draining the land is no longer a realistic option. | [60] | ||

| 21 | Peatland protection represents only a very small reduction in greenhouse gases. | [8,24] | ||

| 22 | Decades of peatland drainage have caused biodiversity loss. | [15,16,17] | ||

| b2. Perceived responsibility | 23 | My engagement in nature protection could set an example for other farmers. | [49,61] | |

| 37 | The main responsibility for peatland protection lies with the farmers. | [20,39,54] | ||

| b3. Self-/group efficacy | 2 | Cooperative management only complicates farming. | [33] | |

| 7 | For cooperation to be effective, it is OK for some farmers to put in more effort than others. | [25] | ||

| 9 | Deciding on a cooperative rewetting option is more difficult when the farmers have diverse land uses. | [28] | ||

| 13 | The more often we (farmers) communicate, the more successful the outcome of the measure. | [62] | ||

| 15 | Large scale action across farms will help to slow down peat soil subsidence. | [9] | ||

| 19 | If we farmers can work as a cooperative unit, we can demonstrate that we are committed to societal demands. | [27,44] | ||

| c. Social norms | c1. Injunctive norms | 3 | A common interest between cooperating farmers is unimportant–we are only business partners. | [14] |

| 8 | I know that society appreciates efforts of the collectives. | [63] | ||

| 11 | A good farmer should be able to work independently. | [51] | ||

| 12 | Other farmers are competitors rather than cooperators. | [51] | ||

| 26 | I am convinced that we as a collective have the duty to act against peat soil subsidence. | [64] | ||

| 27 | If I join for rewetting measures it will be appreciated by other members in the collective. | [39] | ||

| 28 | The measures I take can also help my neighbour(s) to realize future-proof agriculture in the region of my collective. | [65] | ||

| 29 | It is crucial to have a lead farmer during a cooperative farming activity. | [30,56] | ||

| c2. Descriptive norms | 14 | Good agricultural land on peat soil has to be drained. | [58] | |

| 16 | The peat meadow landscape is unique and should be kept as it is. | [9] | ||

| 24 | Farmers are first and foremost producers of agricultural goods, not land stewards. | [30] | ||

| 25 | I currently feel under great pressure from the public to implement environmental protection measures. | [14] |

Appendix B

The distribution is forced and quasi-normal. Below the ranking bar (minus four [−4], strongly disagree, to plus four [+4], strongly agree), the numbers in brackets correspond to statement numbers. A beginning extract of each statement is also shown.

Figure A1.

Example of a completed statement ranking (Q-sort) by one of the participants.

Figure A1.

Example of a completed statement ranking (Q-sort) by one of the participants.

References

- Greifswald Mire Centre. Peatlands in the EU; Greifswald Mire Centre: Greifswald, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Deru, J.; Bloem, J.; De Goede, R.; Keidel, H.; Kloen, H.; Rutgers, M.; Van den Akker, J.; Brussaard, L.; Van Eekeren, N. Soil ecology and ecosystem services of dairy and semi-natural grasslands on peat. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2018, 125, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuis, H.S.; Schokking, F. Land subsidence in drained peat areas of the Province of Friesland, the Netherlands. Q. J. Eng. Geol. 1997, 30, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hardeveld, H.A.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Schot, P.P.; Wassen, M.J. Supporting collaborative policy processes with a multi-criteria discussion of costs and benefits: The case of soil subsidence in Dutch peatlands. Land Use Policy 2018, 77, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, J.; Van Schie, A.; Van Hardeveld, H.A. Pressurized drainage can effectively reduce subsidence of peatlands-lessons from polder Spengen, the Netherlands. Proc. Int. Assoc. Hydrol. Sci. 2020, 382, 741–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van den Born, G.J.; Kragt, F.; Henkens, D.; Rijken, B.; Van Bemmel, B.; Van der Sluis, S. Dalende Bodems, Stijgende Kosten; Planbureau Voor de Leefomgeving: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Tanneberger, F.; Appulo, L.; Ewert, S.; Lakner, S.; Ó Brolcháin, N.; Peters, J.; Wichtmann, W. The Power of Nature-Based Solutions: How Peatlands Can Help Us to Achieve Key EU Sustainability Objectives. Adv. Sustain. Syst. 2021, 5, 2000146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joosten, H. The Global Peatland CO2 Picture; Wetlands International: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pelsma, T.A.H.M.; Motelica-Wagenaar, A.M.; Troost, S. A social costs and benefits analysis of peat soil-subsidence towards 2100 in 4 scenarios. Proc. Int. Assoc. Hydrol. Sci. 2020, 382, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Glenk, K.; Faccioli, M.; Martin-Ortega, J.; Schulze, C.; Potts, J. The opportunity cost of delaying climate action: Peatland restoration and resilience to climate change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2021, 70, 102323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Querner, E.P.; Jansen, P.C.; van den Akker, J.J.H.; Kwakernaak, C. Analysing water level strategies to reduce soil subsidence in Dutch peat meadows. J. Hydrol. 2012, 446–447, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weideveld, S.T.J.; Liu, W.; van den Berg, M.; Lamers, L.P.M.; Fritz, C. Conventional subsoil irrigation techniques do not lower carbon emissions from drained peat meadows. Biogeosciences 2021, 18, 3881–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uda, S.K.; Hein, L.; Adventa, A. Towards better use of Indonesian peatlands with paludiculture and low-drainage food crops. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 28, 509–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, J.R.; Mc Gloin, A. Environmental co-operatives as instruments for delivering across-farm environmental and rural policy objectives: Lessons for the UK. J. Rural. Stud. 2007, 23, 472–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carless, D.; Luscombe, D.J.; Gatis, N.; Anderson, K.; Brazier, R.E. Mapping landscape-scale peatland degradation using airborne lidar and multispectral data. Landsc. Ecol. 2019, 34, 1329–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Food Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations. Peatlands Mapping and Monitoring: Recommendations and Technical Overview; Food Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minayeva, T.; Bragg, O.; Sirin, A. Peatland biodiversity and its restoration. In Peatland Restoration and Ecosystem Services: Science, Policy and Practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Parry, L.E.; Charman, D.J. Modelling soil organic carbon distribution in blanket peatlands at a landscape scale. Geoderma 2013, 211–212, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonn, A.; Reed, M.S.; Evans, C.D.; Joosten, H.; Bain, C.; Farmer, J.; Emmer, I.; Couwenberg, J.; Moxey, A.; Birnie, D.; et al. Investing in nature: Developing ecosystem service markets for peatland restoration. Ecosyst. Serv. 2014, 9, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haefner, K.; Piorr, A. Farmers’ perception of co-ordinating institutions in agri-environmental measures—The example of peatland management for the provision of public goods on a landscape scale. Land Use Policy 2021, 107, 104947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, J.; Sunderland, T.; Ghazoul, J.; Pfund, J.L.; Sheil, D.; Meijaard, E.; Venter, M.; Boedhihartono, A.K.; Day, M.; Buck, L.E.; et al. Ten principles for a landscape approach to reconciling agriculture, conservation, and other competing land uses. PNAS Spec. Feature Perspect. 2013, 110, 8349–8356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buschmann, C.; Röder, N.; Berglund, K.; Berglund, Ö.; Lærke, P.E.; Maddison, M.; Mander, Ü.; Myllys, M.; Osterburg, B.; van den Akker, J.J.H. Perspectives on agriculturally used drained peat soils: Comparison of the socioeconomic and ecological business environments of six European regions. Land Use Policy 2020, 90, 104181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prager, K. Agri-environmental collaboratives for landscape management in Europe. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 12, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reed, M.S.; Moxey, A.; Prager, K.; Hanley, N.; Skates, J.; Bonn, A.; Evans, C.D.; Glenk, K.; Thomson, K. Improving the link between payments and the provision of ecosystem services in agri-environment schemes. Ecosyst. Serv. 2014, 9, 44–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riley, M.; Sangster, H.; Smith, H.; Chiverrell, R.; Boyle, J. Will farmers work together for conservation? The potential limits of farmers’ cooperation in agri-environment measures. Land Use Policy 2018, 70, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, R. Peatbogs and Carbon: A Critical Synthesis to Inform Policy Development in Oceanic Peat Bog Conservation in the Context of Climate Change; University of East London, London, UK: 2010. Available online: http://www.rspb.org.uk/Images/Peatbogs_and_carbon_tcm9-255200.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- Siebert, R.; Toogood, M.; Knierim, A. Factors affecting european farmers’ participation in biodiversity policies. Sociol. Rural. 2006, 46, 318–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijman, J. Agricultural Cooperatives in the Netherlands: Key Success Factors; International Summit of Cooperatives: Quebec, QC, Canada, 2016; Available online: https://library.wur.nl/WebQuery/wurpubs/fulltext/401888 (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- Terwan, P.; Deelen, J.G.; Mulders, A.; Peeters, E. The Cooperative Approach under the New Dutch Agri-Environment Climate Scheme; Ministry of Economic Affairs: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2016; Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/sites/enrd/files/w12_collective-approach_nl.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2021).

- Penker, M. Organising Adaptive and Collaborative Landscape Stewardship on Farmland. In The Science and Practice of Landscape Stewardship; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017; pp. 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BoerenNatuur. Agriculture Turns the Netherlands Green; BoerenNatuur: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2019; Available online: https://www.boerennatuur.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/BN-brochure19x19-ENG-web-1.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2021).

- Zabala, A.; Sandbrook, C.; Mukherjee, N. When and how to use Q methodology to understand perspectives in conservation research. Conserv. Biol. 2018, 32, 1185–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Walder, P.; Kantelhardt, J. The Environmental Behaviour of Farmers—Capturing the Diversity of Perspectives with a Q Methodological Approach. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 143, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimsrud, K.; Graesse, M.; Lindhjem, H. Using the generalised Q method in ecological economics: A better way to capture representative values and perspectives in ecosystem service management. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 170, 106588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckwell, A.; Fleming, C.; Muurmans, M.; Smart, J.C.R.; Ware, D.; Mackey, B. Revealing the dominant discourses of stakeholders towards natural resource management in Port Resolution, Vanuatu, using Q-method. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 177, 106781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, S.; Stenner, P. Doing Q methodology: Theory, method and interpretation. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2005, 2, 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Miltenburg, J.; Rijn, Vecht & Venen, Utrecht, The Netherlands. Personal Communication, 2020.

- Barghusen, R.; Sattler, C.; Deijl, L.; Weebers, C.; Matzdorf, B. Motivations of farmers to participate in collective agri-environmental schemes: The case of Dutch agricultural collectives. Ecosyst. People 2021, 17, 539–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, K.; Baumann, A.; Löschinger, D.; Matthies, E. Psychology of Environmental Protection: Handbook for Encouraging Sustainable Actions; Oekom: Munich, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Previte, J.; Pini, B.; Haslam-Mckenzie, F. Q methodology and rural research. Sociol. Rural. 2007, 47, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Capano, G.; Toivonen, T.; Soutullo, A.; Fernández, A.; Dimitriadis, C.; Garibotto-Carton, G.; Di Minin, E. Exploring landowners’ perceptions, motivations and needs for voluntary conservation in a cultural landscape. People Nat. 2020, 2, 840–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabala, A. Qmethod: A package to explore human perspectives using Q methodology. R. J. 2014, 6, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hermans, F.; Kok, K.; Beers, P.J.; Veldkamp, T. Assessing Sustainability Perspectives in Rural Innovation Projects Using Q-Methodology. Sociol. Rural. 2012, 52, 70–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, L.A.; Calo, A. Assemblage and the ‘good farmer’: New entrants to crofting in scotland. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 80, 532–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairweather, J.R.; Klonsky, K. Response to Vanclay et al. on farming styles: Q methodology for identifying styles and its relevance to extension. Sociol. Rural. 2009, 49, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, R.J.F.; Kuczera, C.; Schwarz, G. Exploring farmers’ cultural resistance to voluntary agri-environmental schemes. Sociol. Rural. 2008, 48, 16–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, E.; Riley, M.; Spees, J. Good farming beyond farmland—Riparian environments and the concept of the ‘good farmer’. J. Rural. Stud. 2019, 67, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.; Kovács, E.; Herzon, I.; Villamayor-Tomas, S.; Albizua, A.; Galanaki, A.; Ioanna, G.; Davy, M.; Johanna Alkan, O.; Zinngrebe, Y. 2021 Simplistic understandings of farmer motivations could undermine the environmental potential of the common agricultural policy. Land Use Policy 2020, 101, 105136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schomers, S.; Matzdorf, B. Payments for ecosystem services: A review and comparison of developing and industrialized countries. Ecosyst. Serv. 2013, 6, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunder, S.; Börner, J.; Ezzine-De-Blas, D.; Feder, S.; Pagiola, S. Payments for environmental services: Past performance and pending potentials. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2020, 12, 209–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, S.B. Independence and individualism: Conflated values in farmer cooperation? Agric. Hum. Values 2015, 32, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerink, J.; Jongeneel, R.; Polman, N.; Prager, K.; Franks, J.; Dupraz, P.; Mettepenningen, E. Collaborative governance arrangements to deliver spatially coordinated agri-environmental management. Land Use Policy 2017, 69, 176–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ziegler, R.; Wichtmann, W.; Abel, S.; Kemp, R.; Simard, M.; Joosten, H. Wet peatland utilisation for climate protection: An international survey of paludiculture innovation. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2021, 5, 100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dijk, W.F.A.; Lokhorst, A.M.; Berendse, F.; de Snoo, G.R. Collective agri-environment schemes: How can regional environmental cooperatives enhance farmers’ intentions for agri-environment schemes? Land Use Policy 2015, 42, 759–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, J.R.; van der Zee, E.; Beunen, R.; Kat, R.; Feindt, P.H. Trusting the People and the System. The Interrelation Between Interpersonal and Institutional Trust in Collective Action for Agri-Environmental Management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banerjee, S.; De Vries, F.P.; Hanley, N.; Van Soest, D.P. The impact of information provision on agglomeration bonus performance: An experimental study on local networks. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2014, 96, 1009–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin-Ortega, J.; Glenk, K.; Byg, A. How to make complexity look simple? Conveying ecosystems restoration complexity for socio-economic research and public engagement. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holden, J.; Bonn, A.; Reed, M.; Buckmaster, S.; Walker, J.; Evans, M.; Worrall, F. Peatland conservation at the science–practice interface. In Peatland Restoration and Ecosystem Services: Science, Policy and Practice; Bonn, A., Allott, T., Evans, Joosten, J., Stoneman, R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzybowski, M.; Glińska-Lewczuk, K. The principal threats to the peatlands habitats, in the continental bioregion of Central Europe—A case study of peatland conservation in Poland. J. Nat. Conserv. 2020, 53, 125778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterschap Amstel, Gooi en Vecht. Proef Natte Landbouw Ankeveen. 2019. Available online: https://www.agv.nl/werk-in-uitvoering/proef-natte-landbouw-ankeveen/ (accessed on 2 June 2021).

- Groeneveld, A.N.; Peerlings, J.H.M.; Bakker, M.M.; Polman, N.B.P.; Heijman, W.J.M. Effects on participation and biodiversity of reforming the implementation of agri-environmental schemes in the Netherlands. Ecol. Complex. 2019, 40, 100726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falconer, K. Farm-level constraints on agri-environmental scheme participation: A transactional perspective. J. Rural. Stud. 2000, 16, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.M.; Lapinski, M.K.; Liu, R.W.; Zhao, J. Long-term effects of payments for environmental services: Combining insights from communication and economics. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holden, J.; Chapman, P.J.; Labadz, J.C. Artificial drainage of peatlands: Hydrological and hydrochemical process and wetland restoration. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 2004, 28, 95–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pilat, J.; Noardlike Fryske Wâlden, Friesland, The Netherlands. Personal Communication, 2020.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).