Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage: The Amazonian Kichwa People

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Contextualization of the Amazonian Kichwa Nationality

2.1. Self-Definition

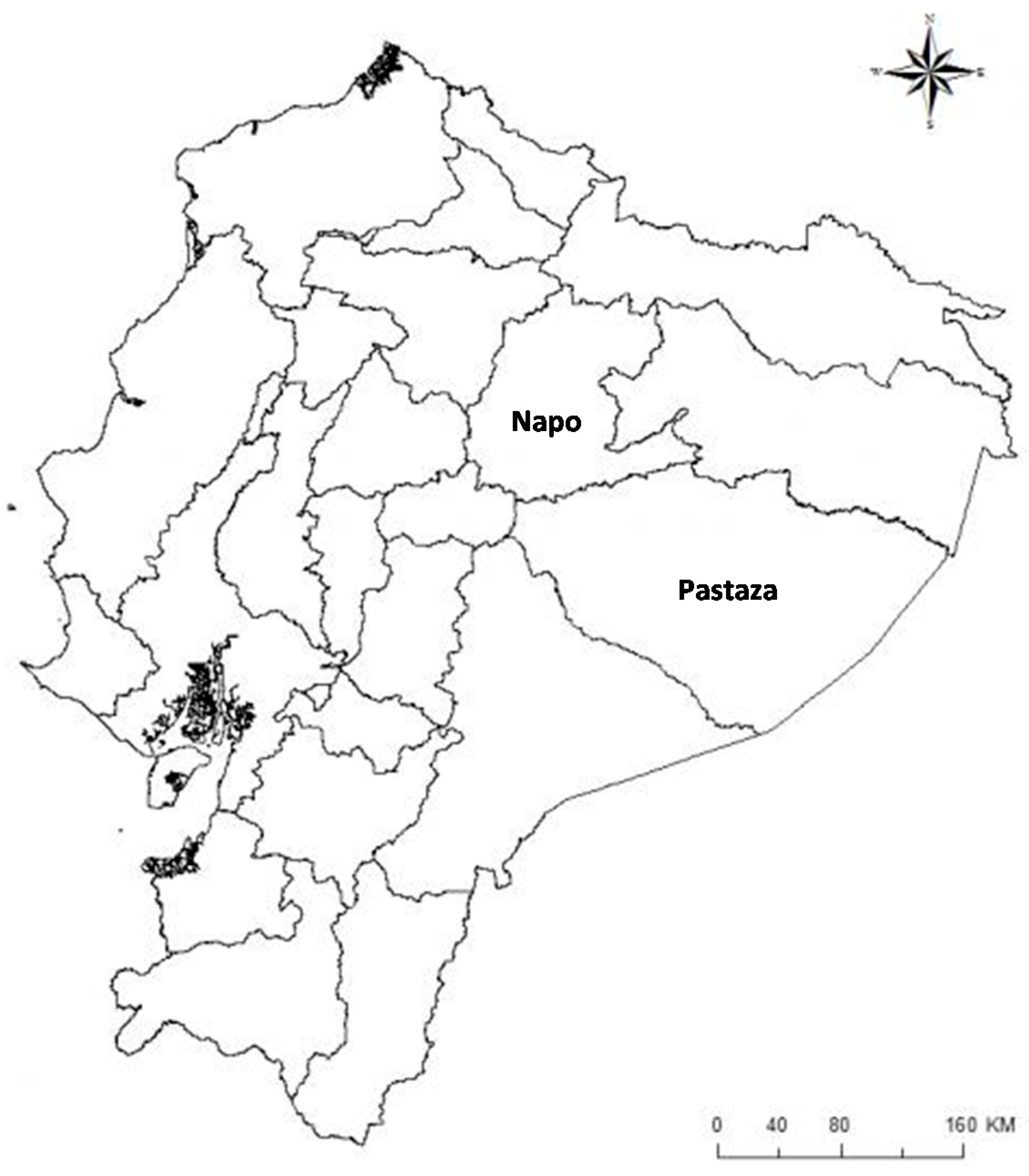

2.2. Nationality Spatiality

2.3. Temporality

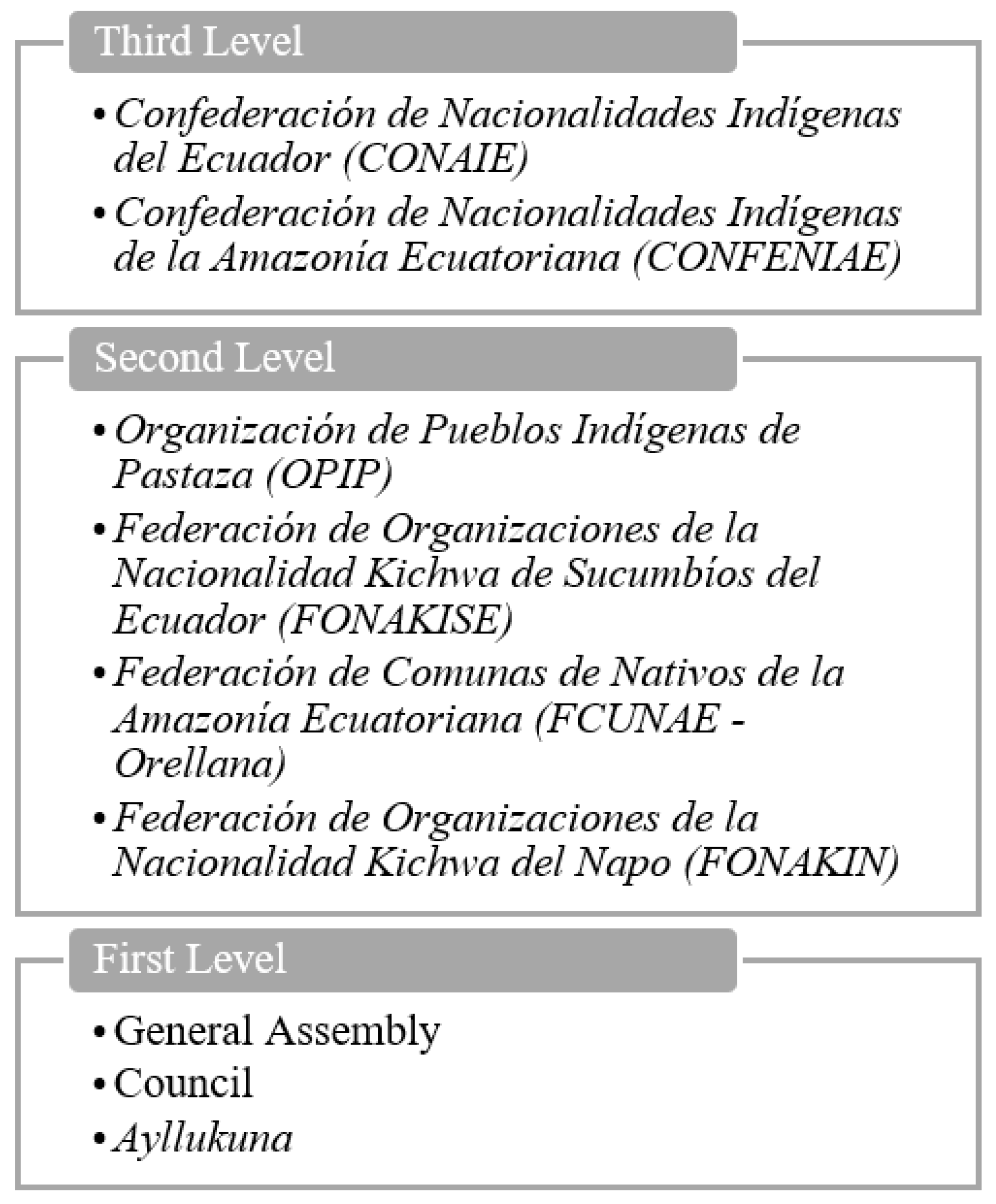

2.4. Social, Political and Economic Organization of the Nationality

2.5. Space-Time Organization

2.6. Reciprocity Practices

3. Identification of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH)

3.1. Methods and Materials

3.2. Oral Expressions

3.3. Face Paints

| Kichwa | Materials |

|---|---|

| Inayu | Splinter of a palm species |

| Wamak tullu | Guadua Splinter |

| Kallana | Earthenware plate |

| Shiwa panka tullu | Unguragua Leaf Splinter |

| Chili panka tullu | Fibre sheet splinter |

| Wituk muyu | Fruit of Wituk |

| Pilchi | Pilchi bowel |

| Shikita | Natural grater |

| Cuchillo | Knife |

| Sacha muyukuna | Wild fruits |

| Chunta kaspi | Chonta splinter |

| Nina | Candle |

| Putu | Cotton |

| Yaku | Water |

| Panka | Leaves |

3.4. Traditional Craft Techniques

3.5. Guayusa-Ethnobotany

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leal González, N. Patrimonio cultural indígena y su reconocimiento institucional. Opción 2008, 24, 28–43. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, V.I. Patrimonio Nacional. Poblaciones Indigenas y Patrimonio Intangible. Nuevo Mundo Mundos Nuevos. Nouveaux Mondes Mondes Nouveaux-Novo Mundo Mundos Novos-New World New Worlds. 2013. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/nuevomundo/65998 (accessed on 23 October 2021).

- UNESCO. Declaración de México sobre las políticas culturales. In Conferencia Mundial Sobre las Políticas Culturales; United Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO): Paris, France, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Convención para la Salvaguardia del Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial. 2003. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/culture/ich/index.php?pg=00022 (accessed on 23 October 2021).

- Cultural, I.N. Guia Metodologica para la Salvaguardia del Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial. Quito: Con Clave Esudio. 2013. Available online: https://issuu.com/inpc/docs/salvaguardiainmaterial (accessed on 23 October 2021).

- UNESCO. Living Heritage and Indigenous Peoples. The Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Geritage; United Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO): Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Declaración de Naciones Unidas sobre los Derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas. 2007. Available online: https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/DRIPS_es.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2021).

- UNESCO. Identifying and Inventorying Intangible Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/01856-ES.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2021).

- Andy Alvarado, P.; Calapucha Andy, C.; Calapucha Cerda, L.; López Shiguango, H.; Tanguila Andy, A.; Tanguila Andy, D. Historia Kichwa Amazónca. In Sabiduría de La Cultura Kichwa de La Amazonía Ecuatoriana. Tomo II; Universidad de Cuenca, UNICEF, DINEIB, Eds.; MEGASOFT: Chennai, India, 2012; pp. 117–129. Available online: https://www.educacionbilingue.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/1-Sabiduria-de-la-Cultura-Kichwa-T2_compressed.pdf (accessed on 4 May 2021).

- Vizcaíno, V.A. Chakras, Bosques y Ríos: El Entramado de La Biocultura Amazónica; INIAP Archivo Historico: Quito, Ecuador, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Restrepo, M.; Cabrejas, A. Canelos: Cuna de Pastaza; Casa de la Cultura Ecuatoriana Benjamín Carrión: Quito, Ecuador, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- De Cultura, M. Indigenous or Native Peoples Database: Kichwas Published; Ministerio de Cultura: Quito, Ecuador, 2020; Available online: https://bdpi.cultura.gob.pe/pueblos/kichwa (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- HELVETAS Swiss Intercooperation, Rights and Resources Initiative. Territorio Indígena y Gobernanza: Kichwas de Napo/Indigenous Territory and Governance: Kichwas de Napo. 2020. Available online: https://www.territorioindigenaygobernanza.com/web/necu_13/ (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Castro, N.C.; Tapuy, A.M.G. La Música Kichwa en la Práctica de Danzas Ancestrales de los Estudiantes de la Escuela de Educación Básica Tarqui de la Comunidad Tambayacu, Cantón Archidona, Provincia de Napo, año 2014–2015; Universidad Tecnológica de IdoAmérica: Ambato, Ecuador, 2017; Available online: http://repositorio.uti.edu.ec/handle/123456789/414 (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Toscano, S.A.S. Analysis of the Approach of the Territorial Circumscription of the Kichwa Nationality of the Province of Pastaza (2008–2010); Universidad Politécnica Salesiana: Quito, Ecuador, 2011; Available online: http://bibliotecavirtualoducal.uc.cl:8081/handle/123456789/1443893 (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- HELVETAS Swiss Intercooperation, Rights and Resources Initiative. Kichwas de Pastaza: The Construction of an Autonomous Government Proposal. 2020. Available online: https://www.territorioindigenaygobernanza.com/web/ecu_14/ (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Ayala, E. Historia Del Ecuador I: Época Aborigen y Colonial, Independencia; Universidad Andina Simón Bolívar/Corporación Editora Nacional: Quito, Ecuador, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Albán, A. Sistema Médico Indígena entre los Kichwas Amazónicos: Prácticas Tradicionales e Interculturalidad. Ph.D. Thesis, Escuela Superior Politécnica de Chimborazo, Quito, Ecuador, 2015. Available online: http://repositorio.puce.edu.ec/handle/22000/9845 (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Hortegón, D.; de Ortiguera, T.; Fernández Ruiz de Castro, P.; de Lemos, C. La Gobernación de Los Quijos (1559–1621); IIAP-CETA: Quito, Ecuador, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Garcés, A. Colonial Oppression and Indigenous Resistance. In La Alta Amazonía/ The Upper Amazon; Granero, F.S., Ed.; Abya-Yala (Universidad Politécnica Salesiana): Quito, Ecuador, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Oberem, U. Los Quijos: History of the Transculturation of an Indigenous Group in the Ecuadorian East; Editorial “Gallocapitán”: Quito, Ecuador, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Rumazo, J. The Amazon Region of Ecuador in the Sixteenth Century; Escuela de Estudios Hispano Americanos de Sevilla: Seville, Spain, 1946. [Google Scholar]

- Muratorio, B. Rucuyaya Alonso and The Social and Economic History of Alto Napo 1850–1950; Abya-Yala (Universidad Politécnica Salesiana): Quito, Ecuador, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Uribe Taborda, S.F.; González Serna, A.; Tȏrres Aguia, E. The government of Los Quijos, Sumaco and La Canela. Frameworks of the socio-historical production process of the territory in the Upper Ecuadorian Amazon, 16th–19th centuries. Univ. Rev. Cienc. Soc. Hum. 2020, 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla, W. La Iglesia y Los Dioses Modernos: Historia Del Protestantismo En El Ecuador; Corporación Editora Nacional: Quito, Ecuador, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan, J.L. The Kingdom of Quito in the 17th Century; Ediciones del Banco Central del Ecuador: Quito, Ecuador, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Garcés, L.F. Sources for the study of the Kichwa language and its evangelizing role in Ecuador. An overview. Procesos Rev. Ecuat. Hist. 2018, 151–175. [Google Scholar]

- Magnoni, D. Análisis etnohistórico de las resistencias y transformaciones de los Napo Runa. TRIM Tordesillas Rev. Investig. Multidiscip. 2018, 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Whitten, N. Amazonian Ecuador: An Ethnic Interface in Ecological, Social and Ideological Perspectives. Iwgia. Doc. Kbh. 1978, 34, 5–80. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Biodiversity and Health in the Indigenous Populations of the Amazon; Amazon Cooperation Treaty: Brasília, Brazil, 1995. Available online: https://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=PE1995101456 (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- De la Rosa, F.J.U. La era del caucho en el Amazonas (1870–1920): Modelos de explotación y relaciones sociales de producción. In Anales del Museo de América (No. 12); Subdirección General de Documentación y Publicaciones: Madrid, Spain, 2004; pp. 183–204. [Google Scholar]

- Mongua-Calderón, C. Caucho, frontera, indígenas e historia regional: Un análisis historiográfico de la época del caucho en el Putumayo-Aguarico. Boletín Antropol. 2018, 33, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Otavaleño de Antropología. Ley sobre División Territorial; Instituto Otalvaleño de Antropología-Centro Regional de Investigación: Quito, Ecuador, 1994; Available online: https://repositorio.flacsoandes.edu.ec/bitstream/10469/5412/4/RFLACSO-Sa19.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Gutiérrez-Marín, W. Los misioneros josefinos, su relación con los indígenas y la conformación de la región amazónica. In Misiones, Pueblos Indígenas y La Conformación de La Región Amazónica: Actores, Tensiones y Debates Actuales; Juncosa, J., Garzon, B., Eds.; Abya-Yala (Universidad Politécnica Salesiana): Quito, Ecuador, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Vicuña Cabrera, A. Proceso Socio-Económico sobre la Explotación del Caucho en la Amazonía Ecuatoriana 1850–1920. 1993. Available online: http://repositorio.flacsoandes.edu.ec/handle/10469/285 (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Instituto Geográfico Militar. Atlas Nacional Del Ecuador; Instituto Geográfico Militar-IGM: Quito, Ecuador, 2010; Available online: http://dspace.ucuenca.edu.ec/handle/123456789/5504?locale=es (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Jarrín, P.S.; Carrillo, L.T.; Acosta, G.Z. The internal colony as a current issue: Transformation of the human territory in the Amazonian region of Ecuador. Let. Verdes Rev. Latinoam. Estud. Socioambientales 2016, 20, 22–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kroeger, A.; Barbira-Freedman, F. La Lucha por la Salud en el Alto Amazonas y en los Andes. Centro de Medicina Andina; Abya-Yala (Universidad Politécnica Salesiana): Quito, Ecuador, 1992; Available online: https://rraae.cedia.edu.ec/Record/UPS_6780ae7a2cb24eddad6dac29273c0b6b (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Andy Alvarado, P.; Calapucha Andy, C.; Calapucha Cerda, L.; López Shiguango, H.; Tanguila Andy, A.; Tanguila Andy, D. Samay: La fuerza vital. In Sabiduría de La Cultura Kichwa de La Amazonía Ecuatoriana. Tomo II; Universidad de Cuenca, UNICEF, DINEIB, Eds.; MEGASOFT: Chennai, India, 2012; pp. 117–129. Available online: https://www.educacionbilingue.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/1-Sabiduria-de-la-Cultura-Kichwa-T2_compressed.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Andy Alvarado, P.; Calapucha Andy, C.; Calapucha Cerda, L.; López Shiguango, H.; Tanguila Andy, A.; Tanguila Andy, D. La relación armónica entre los seres humanos y las plantas. In Sabiduría de La Cultura Kichwa de La Amazonía Ecuatoriana. Tomo II; Universidad de Cuenca, UNICEF, DINEIB, Eds.; EGASOFT: Grosseto, Italy, 2012; pp. 225–234. Available online: https://www.educacionbilingue.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/1-Sabiduria-de-la-Cultura-Kichwa-T2_compressed.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- ILO Convention. Convenio No. 169 de La OIT. 1989. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---americas/---ro-lima/documents/publication/wcms_445528.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Nagoya Protocol. Convenio sobre la Diversidad Biológica Naciones Unidas. Protocolo de Nagoya. 2011. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/abs/doc/protocol/nagoya-protocol-es.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Ecuadorian Code of Ingenuity. 2016. Available online: https://www.asle.ec/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/ingenios-09-12-2016.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Dueñas, J.F.; Jarrett, C.; Cummins, I.; Logan–Hines, E. Amazonian Guayusa (Ilex guayusa Loes.): A historical and ethnobotanical overview. Econ. Bot. 2016, 70, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, R.D.M. Factibilidad para la Creación de una Empresa Comercializadora de la Bebida Energizante a Base de Guayusa “Runa” en el Mercado de Guayaquil. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Técnica Particular de Loja, Loja, Ecuador, 2014. Available online: http://repositorio.ucsg.edu.ec/handle/3317/2227 (accessed on 5 May 2021).

| Province | Canton | Parishes |

|---|---|---|

| Napo | Tena | Tena, Ahuano, Carlos Julio Arosemena Tola, Chontapunta, Pano, Puerto Misahuallí, Puerto Napo y Tálag |

| Archidona | Cotundo y San Pablo de Ushpayacu | |

| Quijos | Papallacta | |

| Carlos Julio Arosemana Tola | Carlos Julio Arosemana Tola | |

| Pastaza | Pastaza | Puyo, Canelos, 10 de agosto, Fátima, Montalvo, Río Corrientes, Sarayaku, Tarqui, Tnte. Hugo Ortiz y Veracruz |

| Arajuno | Arajuno y Curaray | |

| Mera | Mera y Madre Tierra | |

| Santa Clara | Santa Clara |

| Manifestation | Description |

|---|---|

| Legend of Kulliur and Lucero Symbolic use: It explains the divinity of the beings that they consider to be protective and benevolent. Detail of the periodicity: Occasional transmission | The settlers asked the god Killa to help them protect themselves from the puma and the dangers that threaten the forest, so the god gave a beautiful, young indigenous woman the opportunity to bear two children in her womb. One day this young woman, in her last preganancy days, went to fetch water from the river to prepare chicha (purple corn drink), but a puma attacked her and killed her. The puma was only satisfied to eat the woman and ignored the two children that were in her womb, so it put them in an ashanga (basket) to eat them later. However, what the puma did not know was that the children had divine origin and as they were sent by the god Killa, that is, the Moon, so they possessed certain powers. By the next morning, the children had already grown into strong young men who managed to escape easily from the puma. They fled with the intention of returning to punish the puma, rid the people of their fear and avenge the death of their earthly mother. Therefore, they devised a plan to build a bridge over the Napo River, with a loose centre so that the pumas that crossed it would fall into the water and drown, but the pumas realized this and chased the brothers, who were more cunning and guided them towards a cave. Dužiru (Lucero) entered first and the pumas followed him, but he was faster and left the cave blocking the back exit with a large stone, while his brother Kuyllur did the same with the entrance to the cave, in such a way that the pumas were locked and hungry inside the cave. Then at night, Killa sent a ray of light for his sons to join him in the sky and from that day on you can hear, on moonlit nights, the pumas roar hungrily from the bowels of the Napo mountain range. |

| Legend of the Sacha Runa Symbolic use: It details the power of spirits and protective and spectral powers to anthropomorphic beings. Detail of the periodicity: Continuous transmission | This legend is based on a very popular belief in the Amazon rainforest and its foothills. It speaks of a being that sometimes takes the form of an old man and whose mission is to scare away hunters and people who want to destroy the forest. That is why if the intentions of those who enter the forest are not good, the Sacha Runa will do everything to scare them away and even make them sick with fever, dizziness and vomiting. Also, when some people enter without any respect they will be frightened by this mythical creature that imitates spectral sounds to chase them out of the forest. |

| Legend of the Yaku Warmi Symbolic use: It details the elements of nature and attributes spectral powers to zoo-anthropomorphic beings Detail of the periodicity: Occasional transmission | It refers to a woman who is usually seen on riverbanks and attracts fishermen with her cry and then drowns them. It is also said that she is capable of turning into a boa, and with her charms she attracts men to become their partners. |

| Tongue-less lizard legend Symbolic use: Mix of historical events typical of the area, with mythical and divine aspects to give new meanings to elements of nature Detail of the periodicity: Transmission in the collective memory of the community, which very few members know | The lizard was one of the animals that sang the most and was also a violinist. Gifted with its beautiful voice, it made the animals be attracted to its music, so the lizard took advantage of this to to eat them. Seeing that the small animals were gradually disappearing in the forest, two brothers of mystical origin called Killiur and Lucero decided to stop the lizard and devised a plan to shut it up and stop it from eating the animals. So they decided to take a drink (liquour) to befriend the lizard and carry out their plan. Once these two brothers became friends with the lizard, they started giving it a lot to drink while it sang. After a moment of trust and a lot of alcohol, the lizard got drunk and the brothers took the opportunity to cut off its tongue so that it could no longer sing, and thus stop eating the forest animals, so it is since then that the lizard has no tongue. |

| Myth of the blind snake Symbolic use: It explains death with mythical aspects and gives new meanings to elements of nature Detail of the periodicity: Continuous transmission, mainly among people who go to work in the mountains or walk in the forest. | If while walking in the mountains or forest one comes across a blind snake, specifically the Amphisbaena bassleri, commonly known as the blind snake or bad omen snake, it means that a person close to or known to those who see the snake is going to die. |

| Guadua water myth Symbolic use: It details the ethnobotanical use of the elements of nature and gives new meanings to their daily activities. Detail of the periodicity: Continuous transmission | It has two parts: the first part says that if you are walking in the forest and you are lost, drinking guadua water will help you find your way. The second part is a belief that appeals to women’s vanity, if they wash their hair with guadua water, it will grow healthy and shiny, so that is why most women in the Amazon have long hair. |

| Illa Yura myth Symbolic use: It explains death with mythical aspects and gives new meanings to elements of nature Detail of the periodicity: It is told every time people go for a walk in the virgin forest, especially in the afternoon | The myth of the Illa Yura or mata palo mentions that if people walking through the mountains or forest come across this type of tree that seems to be composed of only lianas, it is because they or someone close to them is going to die, so as a countermeasure they would burn the tree. Nowadays, you have to walk through virgin rainforest to find this tree. |

| Design | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Name: Reflection of the sun. Representation: Luminous reflection of the sun, on mountains, rivers and roads Used by: It is for the exclusive use of women in cultural events in the community Meaning/body part where it is used/occasions for use: Women paint this design to obtain the energy of the mountains and the luminosity of the sun. Among the Kichwas of the Amazon, the sun controls the weather and provides light. For this reason, women have this design on the front of their face, because a person’s intelligence is right there Colours: Dark black/blue resulting from the Wituk fruit |

| Name: The seeds. Representation: The seeds that the woman sows in her vegetable garden, which at the same time shows the good harvest Used by: Women Meaning/body part where it is used/occasions for use: This design is related to the Kay Pacha and the Uku Pacha. For this reason, the figure is designed from the cheeks to the chin. It is used during marriage Colors: Dark violet obtained from the Shiwangu muyu seed. Nowadays it is also used in a reddish/yellow colour because it is made from the seed of the achiote plant |

| Name: The anaconda. Representation: Vital energy of creation. Used by: Yachak in ceremonial and cultural events Men and warriors Women and pregnant women’s bellies to protect their child Meaning/body part where it is used/occasions for use: The anaconda is the link between the Kay Pacha world and the other energy dimensions Colours: Dark black/blue resulting from the Wituk fruit |

| Name: Lumu tarpuna Representation: Sowing of yucca Used by: Exclusive use by women Meaning/body part where it is used/occasions for use: Protection of yucca plants. It is used on the face Colors: Reddish/yellow made from the seed of the achiote plant |

| Name: The Kuraka Representation: Balanced relationship between man and nature Used by: Yachak Men Meaning/body part where it is used/occasions for use: On walks to visit family accompanied by musical instruments such as the drum, pingullo and turumpa Colours: Dark black/blue resulting from the Wituk fruit |

| Name: The rayu Representation: It emphasizes the leader role that a person has when controlling a group Used by: Women and men Meaning/body part where it is used/occasions for use: It emphasizes that whoever has it painted, has a trained mind and acts efficiently Colours: Dark black/blue resulting from the Wituk fruit |

| Name: Kuyllur and Dužiru Representation: Strength, power, courage and wisdom Used by: Men and women Meaning/body part where it is used/occasions for use: Used by warriors, hunters or, in rituals and ceremonies Colours: Dark black/blue resulting from the Wituk fruit |

| Name: Amazanka Representation: It is used to receive the power of knowledge Used by: Children Meaning/body part where it is used/occasions for use: Hiking in the forest Colours: Dark black/blue resulting from the Wituk fruit |

| Name: Owl Representation: Receiving the power of the owl’s knowledge-intelligence Used by: Children Meaning/body part where it is used/occasions for use: Hiking in the forest Colours: Dark black/blue resulting from the Wituk fruit |

| Name: Anka, ñanpi, yawati Representation: Acquiring skill powers Used by: Men and women Meaning/body part where it is used/occasions for use: The design contains three motifs: the figure of the eagle that symbolizes leadership on a woman’s forehead; the figure on the nose means roads or mountains which one has to cross and deal with life’s obstacles; the design found on the jaw symbolizes the turtle that has a long life Colours: Dark black/blue resulting from the Wituk fruit |

| Name: Charapa Representation: To represent community importance aimed at problem solving Used by: Exclusive use by men Meaning/body part where it is used/occasions for use: The charapa (turtle) is considered a patient animal and achieves a long life. Those who paint this design are of strong character Colours: Dark black/blue resulting from the Wituk fruit |

| Name: Nunkulli Representation: Female fertility Used by: Women Meaning/body part where it is used/occasions for use: The woman who has paju de la siembra, paints three lines with achiote on her cheeks and one line on her chin, representing the yucca stakes. She paints herself like this when she goes sowing. It is used during marriage Colours: Reddish/yellow which is made from the seed of the achiote plant |

| Manifestation | Description |

|---|---|

| Lisan ashanga fabric | The ashanga is a basket generally made of fibre which is extracted from the stalk of the toquilla straw, commonly known in the area as lisan. The weaving starts at the base and goes up in crosses in such a way that diamonds are formed. At the end, the remaining edges of the fibres are knotted between the diamonds. If desired, a strap is braided and tied around the edges to form a bag. Ashangas are used to transport products or to store things. Material: Toquilla straw |

| Shikra fabric | The shikra is useful for carrying things. It is woven in different sizes according to people’s convenience, as it is used for different activities, such as carrying personal belongings when hunting, carrying food or field tools. Material: Pita tree fibre |

| Making the clay pot | The clay pot is an artifact that is used in the community for different purposes, such as: cooking, fermenting chicha and storing food. The vessel has a rounded and flattened base to stand upright, a circular mouth, a circular neck, is orange in colour and has no engravings on it. Material: Made only from clay and the modelling technique is used |

| Lika fabric | The lika is a tool used by the community people for fishing. It is a net made of synthetic material, which is made when fishing, although unlike other tools made from other materials, this one has a longer lifespan. It is circular in shape and is woven loosely in a rhomboid shape. To use it, the open net is cast into a body of water in which you want to fish, and then immediately pulled up by pulling on a rope tied in the middle of the net. If any fish have been caught, they are removed from the net and it is kept for use on another occasion. Material: Nylon |

| Wami fabric | Wami is a tool that the community people use for fishing. It is made every time they go fishing, for which the bark of the toquilla straw is cut into long, thin strips. It has a conical shape and is woven without much separation from the tip to the base, it has the shape of a round mouth. For its use, the open and rounded part is placed in the opposite direction to the current of a stream so that the fish can enter the stream to the bottom and, due to the water, cannot get out of it until a person comes back to check if they have managed to catch something. Material: Toquilla straw |

| Crafts such as necklaces, bracelets, cuffs, traditional costumes and instruments | The elaboration of this seed jewellery is used and made throughout the Amazon region by the different existing nationalities and peoples. Material: Calmito, Ishpa muyu, Anamora, Pishkuma and Achira muyu seeds are used for jewellery. The Pingullo stem is used for flutes. For clothing, the leaves of Piton, Marpindu and Killu sisa are used. |

| Type of Energy | Obtained | Use |

|---|---|---|

| Physical energy | Through the intake of Guayusa | The energy obtained from the Guayusa is released through activities that cause physical exhaustion |

| Spiritual energy | Guayusa as a symbol that provides good energy | Clean |

| Mental energy | Guayusa as a relaxation tool | Guayusa essences and oils for relaxation |

| Type of Use | Body Part/Product | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Medicinal | Central Nervous System | It increases extracellular levels of the neurotransmitters norepinephrine and dopamine, which help the person ingesting it to achieve good concentration and attention. It also reduces sleepiness and tiredness, increasing the body’s energy |

| Cardiovascular system | It develops a positive inotropic effect and increases cardiac output and is therefore used therapeutically as a cardiotonic, diuretic and nerve centre stimulant. | |

| Skeletal muscles | It increases performance in relation to endurance and exercise capacity | |

| Respiratory system | It is a bronchodilator in respiratory diseases | |

| Digestive system | It reduces the risk of colorectal and colon cancer, as well as symptoms and development of gallstones. It also serves as a purgative | |

| Endocrine glands | It increases insulin sensitivity and reduces the risk of diabetes, due to its antioxidant properties | |

| Cosmetic | Anti-cellulite | It prevents excessive fat accumulation in cells |

| Solar filter | Antioxidant properties that help protect skin cells against UV radiation and delays aging | |

| Alopecia | It stimulates hair growth. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Maldonado-Erazo, C.P.; Tierra-Tierra, N.P.; del Río-Rama, M.d.l.C.; Álvarez-García, J. Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage: The Amazonian Kichwa People. Land 2021, 10, 1395. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10121395

Maldonado-Erazo CP, Tierra-Tierra NP, del Río-Rama MdlC, Álvarez-García J. Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage: The Amazonian Kichwa People. Land. 2021; 10(12):1395. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10121395

Chicago/Turabian StyleMaldonado-Erazo, Claudia Patricia, Nancy P. Tierra-Tierra, María de la Cruz del Río-Rama, and José Álvarez-García. 2021. "Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage: The Amazonian Kichwa People" Land 10, no. 12: 1395. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10121395

APA StyleMaldonado-Erazo, C. P., Tierra-Tierra, N. P., del Río-Rama, M. d. l. C., & Álvarez-García, J. (2021). Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage: The Amazonian Kichwa People. Land, 10(12), 1395. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10121395