Establishing Regional Power Sustainability and Feasibility Using Wind Farm Land-Use Optimization

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Importance of Renewable Energy

1.2. Wind Energy

1.3. Area of Interest (AOI)

1.4. Energy Situation in Jordan

2. Methodology and Criteria Evaluation

2.1. Preparation of Land Suitability Data

2.2. Determination of Suitability Score and Weight Values

2.3. Determination of Suitability Score and Weight Values

3. Results

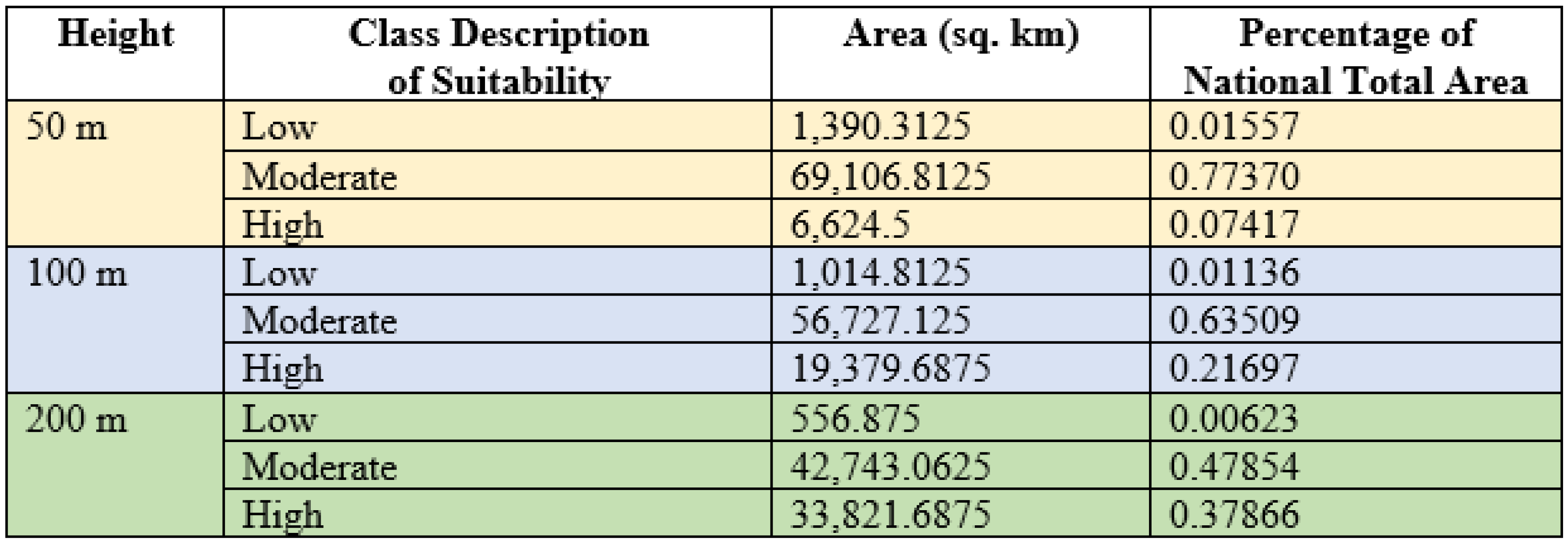

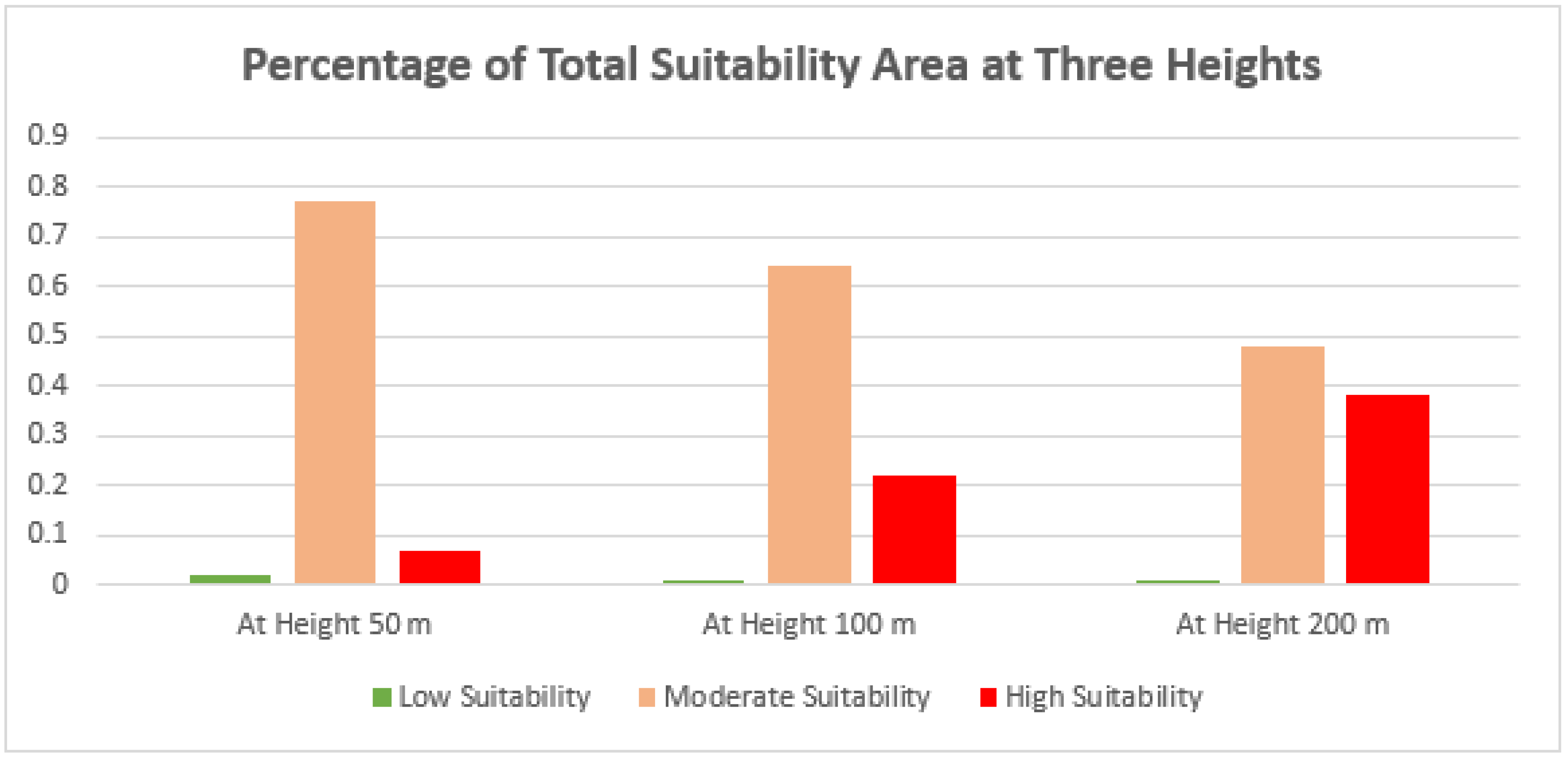

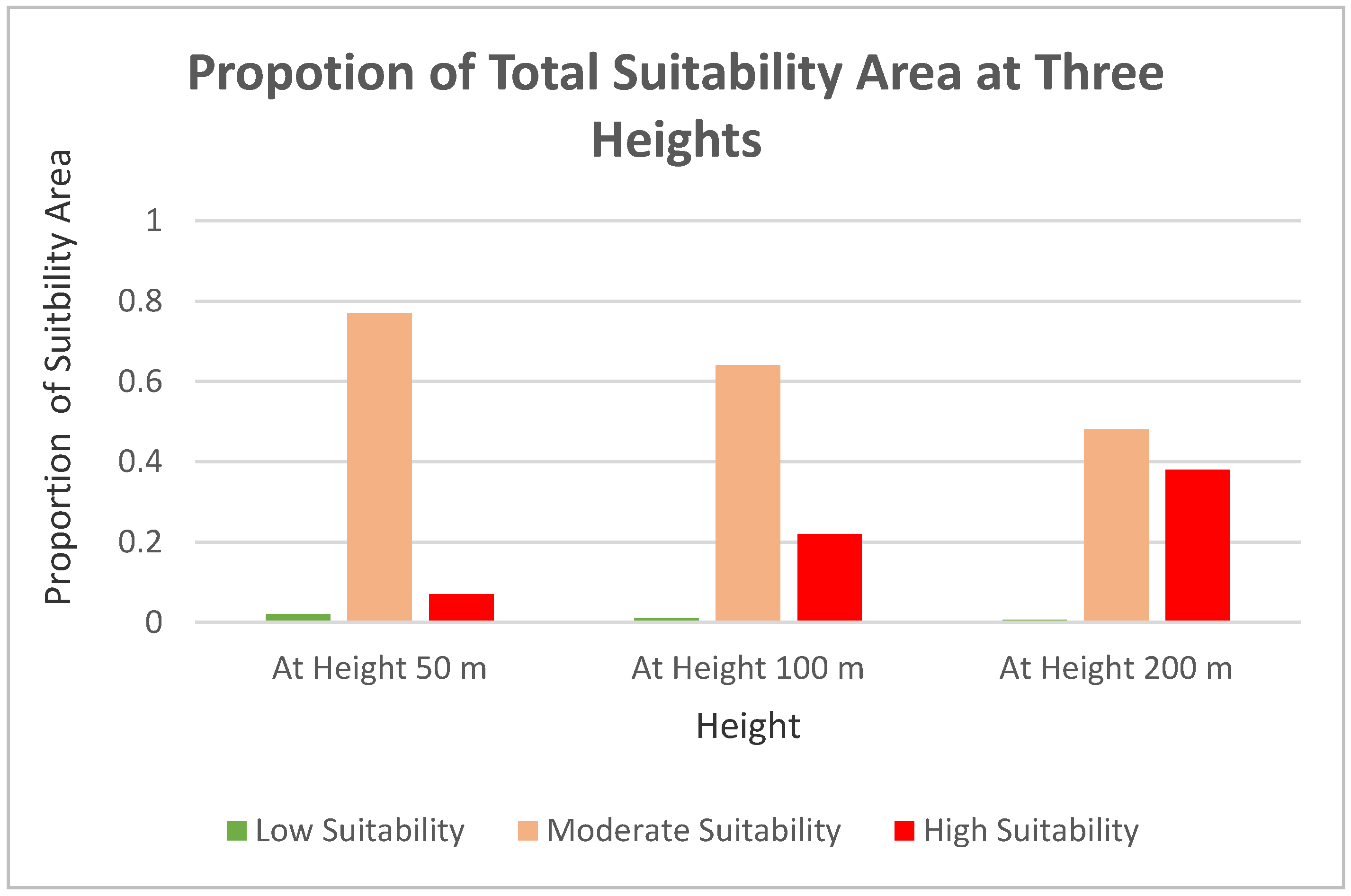

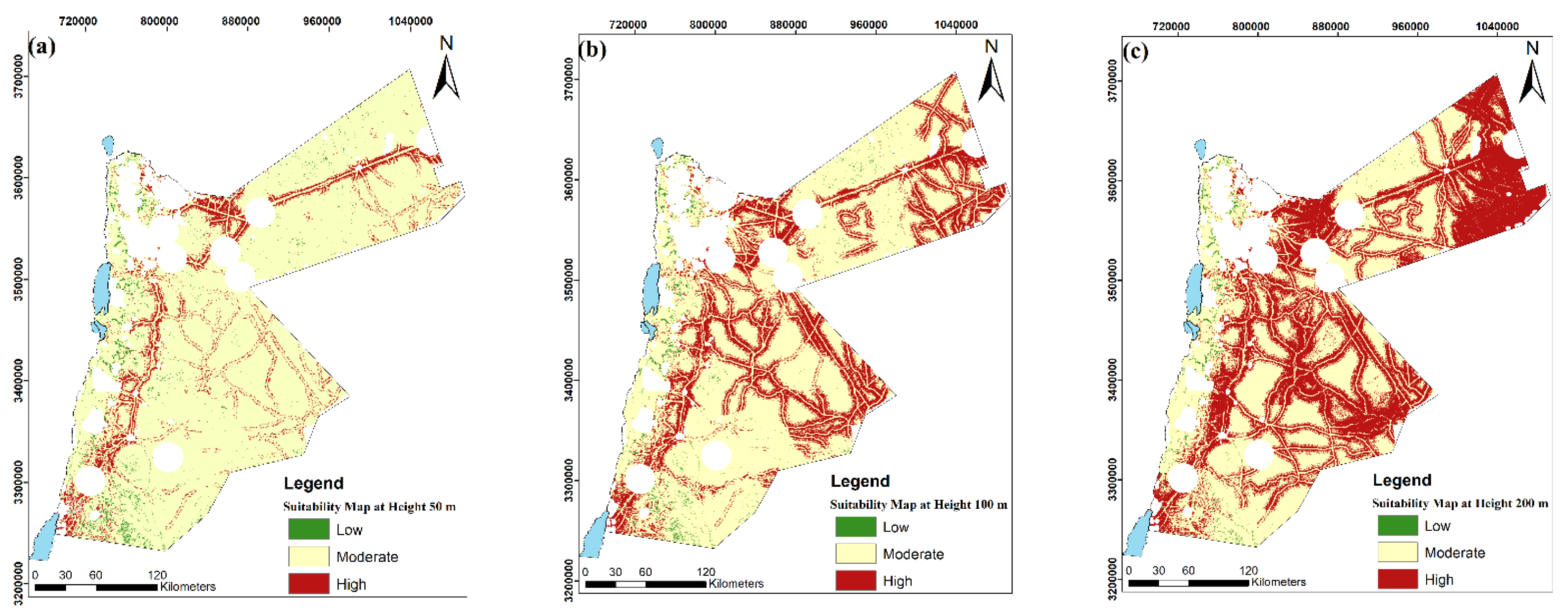

3.1. Land Suitability Results Based on Turbine Hub Height

3.2. Findings Identified by Region

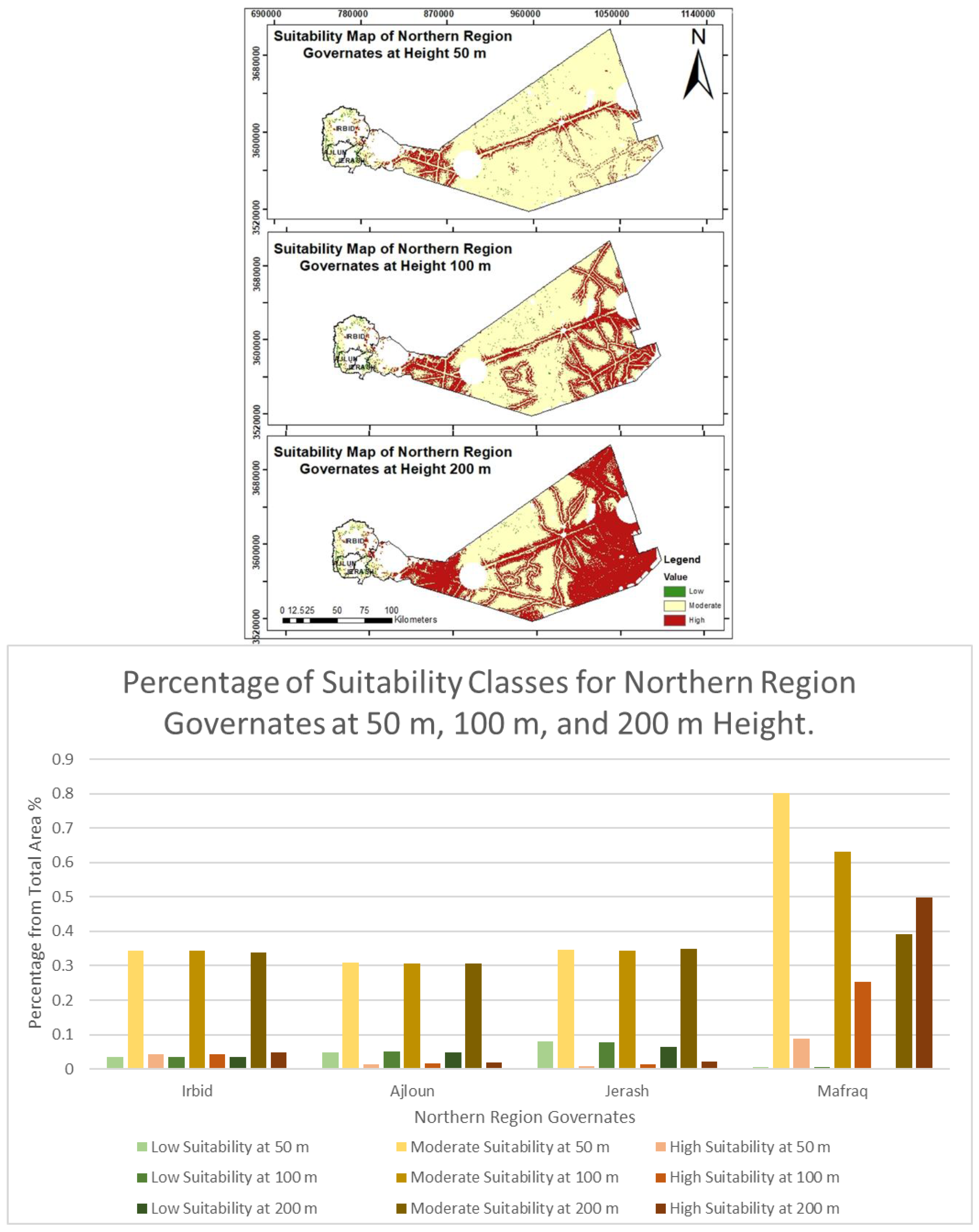

3.2.1. Northern Region

3.2.2. Central Region

3.2.3. Southern Region

3.3. Feasibility Study Based on the Results

- Pcost to gen: cost to generate power. FCR: fixed charge rate.

- IC: initial capital, $.

- AEP: net annual energy production, kWh.

- LRC: levelized replacement cost, $.

- O&M: cost for operations and maintenance, $.

- LLC: land lease cost, $/year, $.

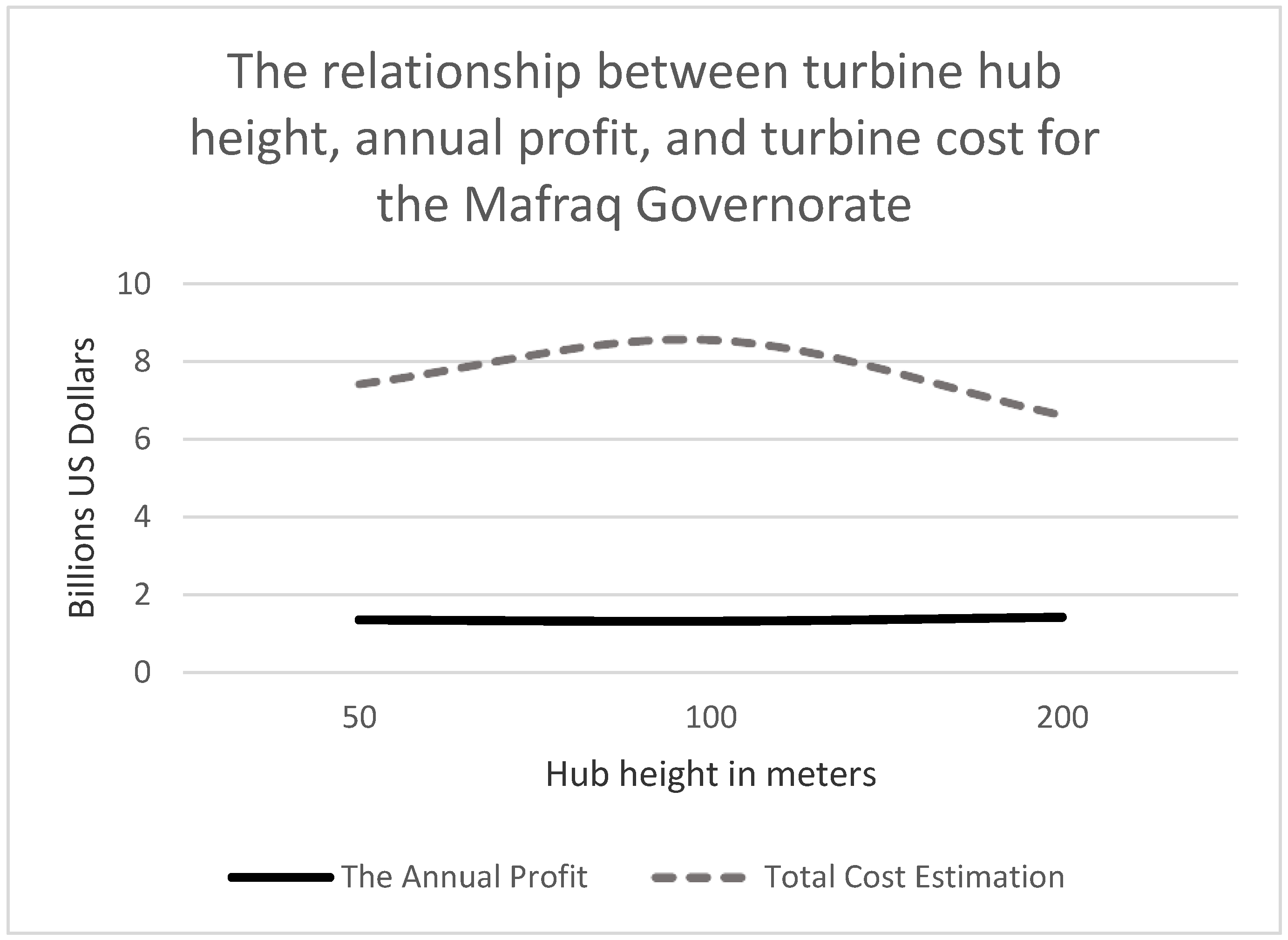

3.4. Implementing the Study on the Northern Region/Mafraq Governorate

3.5. The Developed Framework

4. Discussion

- Providing a new land-use planning system that supports and protects the lands designated for generating wind energy to enable all areas to operate with high productivity while providing the necessary energy for that. This is established by creating a land-use layer indicating the suitability of land for wind farm installations. In this respect, the United States is one of the leading nations [78]. India, too, is working to close energy gaps for its rapidly expanding population by developing maps for solar and wind suitability classes [93]. A consolidated effort is being made to unify constraints for appropriate land selection for onshore wind installations on a European scale [94].

- Creating controlled-climate agricultural areas in which agriculture can depend on modern concepts for lush growth. As long as the necessary energy for irrigation, lighting, and climate control is available, we can speed up production processes and develop more productive crop-based needs to create food security for an expanding population. In addition to the direct employment opportunities in wind farm installations, there are indirect employment opportunities in the investment projects. For example, wind power farms indirectly boosted the Brazilian agricultural employment levels by 64% and the wages by 131% [95]. They found that it also boosted the industrial and construction sectors, especially among the less-educated population, enhancing the social and economic status of their families and increasing social welfare in this developing nation. An earlier study on “valuing the attributes of renewable energy investments” also found that the benefits of renewable energy projects are mainly on the socioeconomics of the rural population [96].

- Producing the energy needed to establish new industrial cities in remote areas and providing the necessary infrastructure. This will create new job opportunities, increase gross domestic product, and enhance industrial production, which will positively affect exports. Such projects will create employment opportunities and encourage migration to rural areas. A recent study in Wales, UK, that investigated the complex investment in energy and other industries showed that success is also related to the amount of local capital. Therefore, when the regional investment falls short, investment is more likely to be handled at the national level than locally to maintain its sustainability [97].

- Instead of living in the areas most suitable for farming, the wind farm project will encourage the urbanization of more arid regions to spare the fertile lands for food production. When energy is readily available, many challenging living conditions may be overcome such as the souring hot days when energy is so cheap to cool the living quarters. Also, with readily available energy, the creation of smart cities becomes attractive. A living example is Masdar City in Abu Dhabi, the United Arab Emirates, which stands as a model for a smart, sustainable city benefiting from solar energy [98]. If established in remote arid areas, this will also secure jobs for the new agglomerations and prevent migration to big cities.

5. Conclusions

6. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Criteria | Average% |

|---|---|

| Wind Speed | 66.5% |

| Wind Power Density | 43.8% |

| Proximity to Urban Areas | 22% |

| Electrical power Lines | 19.8 |

| Highway and Railway Roads | 13.6% |

| Attitude | 13.6% |

| Distance to Protected Areas | 13% |

| Slope | 10.9% |

| Land Use/ Land Cover | 10% |

| Important Places | 10% |

| Population Density | 8.4% |

| Proximity to Forest | 6.45% |

| Proximity to Water Bodies | 5.2% |

| Distance to Airports | 2.7% |

| Proximity to Village Areas | 2.2% |

Appendix B

| Criteria | Data Source | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Land Use /Land Cover | Royal Jordanian Geographic Center (RJGC) derived from Landsat 8, 2016. | Vector (polygon) |

| Roads | Open Street Map. https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=7/31.300/37.131 (accessed on 3 February 2021) | Vector (line) |

| Electrical Power Lines | Open Street Map. https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=7/31.300/37.131 (accessed on 3 February 2021) | Vector (line) |

| Digital Elevation Model/DEM | Alaska Satellite Facility, 12.5-meter resolution, 2019. https://www.asf.alaska.edu/ (accessed on 3 February 2021) | Raster |

| Wind Speed | Global Wind Atlas, 2019. https://globalwindatlas.info/en/area/Jordan?print=true (accessed on 3 February 2021) | Raster |

| Wind Power Density | Global Wind Atlas, 2019. https://globalwindatlas.info/en/area/Jordan?print=true (accessed on 3 February 2021) | Raster |

| Potential Earthquake Hazard | Jaradat, R.A., Nusier, O.K., Awawdeh, M.M., Al-Qaryouti, M.Y., Fahjan, Y.M. and Al-Rawabdeh, A.M., 2008. Deaggregation of probabilistic ground motions for selected Jordanian cities. Jordan Journal of Civil Engineering, 2(2), 172–196, 2008. | Raster |

| Environmental Preservations | Digitized by the Author. https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=13/29.8354/35.2831 (accessed on 3 February 2021) | Vector (Polygon) |

| Military Airport | Digitized by the Author. https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=13/29.8354/35.2831 (accessed on 3 February 2021) | Vector (Point) |

| Commercial Airport | Digitized by the Author. https://www.openstreetmap.org/#map=13/29.8354/35.2831 (accessed on 3 February 2021) | Vector (Point) |

Appendix C

Appendix D

Appendix E

Appendix F. Finding Values for the Equations at the Three Different Heights: 50 m, 100 m, and 200 m

- FCR = 0.01

- IC: the initial cost for each turbine (million USD).

- IC = $1.3 million USD, for a wind turbine of 1 MW at a height of 50 m.

- IC = $3 million USD, for a wind turbine of 2 MW at a height of 100 m.

- IC = $4 million USD, for a wind turbine of 3.45 MW at a height of 200 m.

- AEP: for annual energy production, assume a 35% capacity factor (according to the nameplate rating; the turbine will generate an average of 35%).

- For a height of 50 m:

- AEP = 1000 kW × 24 hr/day × 365 day/year × 0.35

- AEP = 3,066,000 kWh/year

- For a height of 100 m:

- AEP = 2000 kW × 24 hr/day × 365 day/year × 0.35

- AEP = 6,132,000 kWh/year

- For a height of 200 m:

- AEP = 3450 kW × 24 hr/day × 365 day/year × 0.35

- AEP = 10,577,700 kWh/year

- LRC: The Leveled Replacement cost is: (Cost of Turbine/ Expected Life). Turbine life expectancy is 25 years.

- For a height of 50 m:

- LRC = $1.3 million USD/25years

- LRC = $52,000 USD/year

- For a height of 100 m:

- LRC = $3 million USD/25years

- LRC = $120,000 USD/year

- For a height of 200 m:

- LRC = $4 million USD/25years

- LRC = $160,000 USD/year

- O&M: Operations and Maintenance cost. According to American Wind Energy Association (AWEA), O&M is estimated at 8% of annual gross revenue.

- According to NEPCO, each 1 kWh is sold by $0.11.

- For a height of 50 m:

- O&M = AEP × average gross revenue/kWh × 0.08

- O&M = 3,066,000 × 0.11 × 0.08

- O&M = $26,980.8 USD

- For a height of 100 m:

- O&M = AEP × average gross revenue/kWh × 0.08

- O&M = 6,132,000 × 0.11 × 0.08

- O&M = $53,961.6 USD

- For a height of 200 m:

- O&M = AEP × average gross revenue/kWh × 0.08

- O&M = 10,577,700 × 0.11 × 0.08

- O&M = $93,083.76 USD

- LLC: The land lease cost, according to AWEA statics is estimated at 5% of annual revenue.

- LLC = $10,000 USD

- Pcost to gen = [(FCR × IC)/AEP] + [(LRC + O&M + LLC)/AEP].

- For a height of 50 m:

- Pcost to gen = [(0.01 × 1,300,000)/3,066,000] + [(52,000 + 26,980.8 + 10,000)/3,066,000].

- Pcost to gen = [0.0042] + [0.029].

- Pcost to gen = 0.033

- Pcost to gen = 3.3 c/kWh (cent per kilowatt hour).

- For a height of 100 m:

- Pcost to gen = [(0.01 × 3,000,000)/6,132,000] + [(120,000 + 53,961.6 + 10,000)/6,132,000].

- Pcost to gen = [0.0049] + [0.030].

- Pcost to gen = 0.035

- Pcost to gen = 3.5 c/kWh (cent per kilowatt hour).

- For a height of 200 m:

- Pcost to gen = [(0.01 × 4,000,000)/10,577,700] + [(160,000 + 93,083.76 + 10,000)/10,577,700].

- Pcost to gen = [0.0038] + [0.025].

- Pcost to gen = 0.029

- Pcost to gen = 2.9 c/kWh (cent per kilowatt hour).

- To find the total Annual Expenses:

- Tae = Pcost to gen × AEP

- Tae: total annual expenses

- Pcost to gen: cost to generate power.

- AEP: net annual energy production, kWh.

- For a height of 50 m:

- Tae = $0.033 kwh × 3,066,000 kWh/year

- Tae = $101,178 USD

- For a height of 100 m:

- Tae = $0.035 kwh × 6,132,000 kWh/year

- Tae = $214,620 USD

- For a height of 200 m:

- Tae = $0.029 kwh × 10,577,700 kWh/year

- Tae = $306,753.3 USD

- To find Annual Gross Income:

- Ig = Tarif Price × AEP

- Ig: annual gross income

- AEP: net annual energy production, kWh.

- For a height of 50 m:

- Ig = 0.11 c/kWh × 3,066,000 kWh/year

- Ig = $337,260 USD

- For a height of 100 m:

- Ig = 0.11 c/kWh × 6,132,000 kWh/year

- Ig = $674,520 USD

- For a height of 200 m:

- Ig = 0.11 c/kWh × 10,577,700 kWh/year

- Ig = $1,163,547 USD

- To find the annual profit (Pa) of the turbine:

- Pa = (Pselling price – Pcost to gen) × AEP

- Pa: annual profit

- Pselling price: selling price power

- Pcost to gen: cost to generate power

- AEP: net annual energy production, kWh.

- For a height of 50 m:

- Pa = ($0.11 – $0.033) × 3,066,000 kWh/year

- Pa = $236,082 USD

- For a height of 100 m:

- Pa = ($0.11 – $0.035) × 6,132,000 kWh/year

- Pa = $459,900 USD

- For a height of 200 m:

- Pa = ($0.11 – $0.029) × 10,577,700 kWh/year

- Pa = $856,793.7 USD

- To calculate how long it will take for this investment to be paid off:

- BEP = Cturbine/Pa

- BEP: Break-Even Point

- Cturbine: turbine cost

- Pa: annual profit

- For a height of 50 m:

- BEP = $1,300,000 USD/$236,082 USD

- BEP = 5.5 years

- For a height of 100 m:

- BEP = $3,000,000 USD/$459,900 USD

- BEP = 6.5 years

- For a height of 200 m:

- BEP = $4,000,000 USD/$856,793.7 USD

- BEP = 4.7 years

Appendix G

| Month | Electrical Energy Consumed (kWh) | The Rank of Electrical Consumption from the Lowest (11) to the Highest (1) |

|---|---|---|

| February | 63,803,956 | 11 |

| January | 64,580,912 | 10 |

| December | 67,633,506 | 9 |

| March | 72,241,688 | 8 |

| April | 72,241,688 | 8 |

| November | 77,284,654 | 7 |

| May | 80,693,540 | 6 |

| June | 86,369,590 | 5 |

| October | 89,975,193 | 4 |

| July | 94,945,598 | 3 |

| September | 97,801,367 | 2 |

| August | 99,353,787 | 1 |

| Total | 132,214,418 kWh/year | |

Appendix H. Calculations of the Feasibility of Installed Wind Turbines in Mafraq Governorate at Three Heights 50 m, 100 m, and 200 m.

- Required area = 6D × 10D

- Required area = 6 (50) × 10 (50)

- Required area = 150,000 m2, convert the area unit to Km2 = 0.15 km2

- Number of turbines = Jordan’s electrical annual energy consumption/annual energy production for each turbine

- Number of turbines = (17,504,000,000 kWh/year)/(3,066,000 kWh/year)

- Number of turbines = 5709

- Area required for 5709 turbines = Number of turbine × area required for each turbine

- Area required for 5709 turbines = 5709 × 0.15 Km2

- Area required for 5709 turbines = 856.35 km2

- Remaining of high suitable area = High suitable area - Area required for 5709 turbines

- Remaining of high suitable area = 2349 km2 − 856.35 km2

- Remaining of high suitable area = 1492.65 km2

- AEPtotal = Number of turbines × AEP for each turbine.

- AEPtotal = 5709 × 3,066,000 kWh/year

- AEPtotal = 17,503,794,000 kWh/year

- The annual profit from 5709 turbine = 5709 turbine × annual profit (Pa) from one turbine at a height of 50 m = 5709 × $236,082 USD.

- The annual profit from 5709turbine = $1,347,792,138 USD

- wind turbine farm in Mafraq at a height of 50 m costs = number of turbines × cost of the turbine.

- wind turbine farm in Mafraq at a height of 50 m costs = 5709 × $1.3 million USD.

- wind turbine farm in Mafraq at a height of 50 m costs = $7,421,700,000 USD

- 5709 turbines are required at a height of 50 m to cover all of Jordan’s electricity needs. The Annual profit will be $1,347,792,138 USD, with cost estimation $7,421,700,000 USD.

- Area of Mafraq at a height of 100 m, high suitability class = 6768.2 km2

- Required area = 6D × 10D

- Required area = 6 (100) × 10 (100)

- Required area = 600,000 m2, convert the area unit to Km2 = 0.6 km2

- Number of turbines = Jordan’s electrical annual energy consumption/annual energy production for each turbine

- Number of turbines = (17,504,000,000 kWh/year)/(6,132,000 kWh/year)

- Number of turbines = 2854

- Area required for 2854 turbines = Number of turbine × area required for each turbine

- Area required for 2854 turbines = 2854 × 0.6 km2

- Area required for 2854 turbines = 1712.4 km2

- Remaining of high suitable area = High suitable area - Area required for 2854 turbines

- Remaining of high suitable area = 6768.2 km2 − 1712.4 km2

- Remaining of high suitable area = 5055.8 km2

- AEPtotal = Number of turbines × AEP for each turbine.

- AEPtotal = 2854 × 6,132,000 kWh/year

- AEPtotal = 17,500,728,000 kWh/year

- The annual profit from 2854 turbines = 2854 turbine × annual profit (Pa) from one turbine at a height of 100 m = 2854 × $459,900 USD.

- The annual profit from 2854 turbine = $1,312,554,600 USD

- wind turbine farm in Mafraq at a height of 100 m costs = number of turbines × cost of the turbine.

- wind turbine farm in Mafraq at a height of 100 m costs = 2854 × $3 million USD.

- wind turbine farm in Mafraq at a height of 100 m costs = $8,562,000,000 USD

- 2854 turbines are required at a height of 100 m to cover all of Jordan’s electricity needs. The Annual profit will be $1,312,554,600 USD, with cost estimation $8,562,000,000 USD.

- Area of Mafraq at height of 200 m, high suitability class = 13,251.8 km2

- Required area = 6D × 10D

- Required area = 6 (150) × 10 (150)

- Required area = 1,350,000 m2, convert the area unit to km2 = 1.35 km2

- Number of turbines = Jordan’s electrical annual energy consumption/annual energy production for each turbine

- Number of turbines = (17,504,000,000 kWh/year)/(10,577,700 kWh/year)

- Number of turbines = 1654

- Area required for 1654 turbines = Number of turbine × area required for each turbine

- Area required for 1654 turbines = 1654 × 1.35 km2

- Area required for 1654 turbines = 2232.9 km2

- Remaining of high suitable area = High suitable area - Area required for 1654 turbines

- Remaining of high suitable area = 13,251.8 km2 − 2232.9 km2

- Remaining of high suitable area = 11,018.9 km2

- AEPtotal = Number of turbines × AEP for each turbine.

- AEPtotal = 1654 × 10,577,700 kWh/year

- AEPtotal = 17,495,515,800 kWh/year

- The annual profit from 1654 turbine = 1654 turbine × annual profit (Pa) from one turbine at a height of 200 m = 1654 × $856,793.7 USD.

- The annual profit from 1654 turbine = $1,417,136,779.8 USD

- wind turbine farm in Mafraq at a height of 200 m costs = number of turbines × cost of the turbine.

- wind turbine farm in Mafraq at a height of 200 m costs = 1654 × $4 million USD.

- wind turbine farm in Mafraq at a height of 200 m costs = $6,616,000,000 USD

- 1654 turbines are required at a height of 200 m to cover all of Jordan’s electricity needs. The Annual profit will be $1,417,136,779.8 USD, with cost estimation $6,616,000,000

References

- Rajakumar, D.G.; Nagesha, N. Sustainability Through Renewable Energy: Economic and Environmental Analysis of Wind Farms in Karnataka. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Adv. Eng. 2012, 2, 396–402. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA. Global Renewables Outlook: Energy transformation 2050; Dhabi, A., Ed.; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WEC. World Energy Insights Brief 2019; Dhabi, A., Ed.; World Energy Council: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- PT. Powering Tomorrow; the Winds of Change and the Power Network. Article 4/6. Arnhem: Det Norske Veritas (DNV). 2020. Available online: https://www.dnv.com/publications/the-winds-of-change-and-the-power-network-186589 (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- Marcu, I.; Suciu, G.; Bălăceanu, C.; Vulpe, A.; Drăgulinescu, A.-M. Arrowhead technology for digitalization and automation solution: Smart cities and smart agriculture. Sensors 2020, 20, 1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Al-Kofahi, S.D.; Gharaibeh, A.A.; Bsoul, E.Y.; Othman, Y.A.; Hilaire, R.S. Investigating domestic gardens’ densities, spatial distribution and types among city districts. Urban. Ecosyst. 2019, 22, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asarpota, K.; Nadin, V. Energy strategies, the urban dimension, and spatial planning. Energies 2020, 13, 3642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chigudu, A.; Chirisa, I. The quest for sustainable spatial planning framework in Zimbabwe and Zambia. Land Use Policy 2020, 92, 104442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bafarasat, A.Z. Reflections on the three schools of thought on strategic spatial planning. J. Plan. Lit. 2015, 30, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajot, S.; Peter, M.; Bahu, J.M.; Guignet, F.; Koch, A.; Maréchal, F. Obstacles in energy planning at the urban scale. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 30, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiremath, R.B.; Shikha, S.; Ravindranath, N.H. Decentralized energy planning; modeling and application—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2007, 11, 729–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dam, J.; Junginger, M.; Faaij, A.P. From the global efforts on certification of bioenergy towards an integrated approach based on sustainable land use planning. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2010, 14, 2445–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. Optimal Coordination Strategies for Load Service Entity and Community Energy Systems Based on Centralized and Decentralized Approaches. Energies 2020, 13, 3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qazi, A.; Hussain, F.; Rahim, N.A.; Hardaker, G.; Alghazzawi, D.; Shaba, K.; Haruna, K. Towards Sustainable Energy: A Systematic Review of Renewable Energy Sources, Technologies, and Public Opinions. IEEE 2019, 7, 63837–63851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoeglehner, G.; Niemetz, N.; Kett, K.-H. Spatial dimensions of sustainable energy systems: New visions for integrated spatial and energy planning. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2011, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mourmouris, J.C.; Potolias, C. A multi-criteria methodology for energy planning and developing renewable energy sources at a regional level: A case study Thassos, Greece. Energy Policy 2013, 52, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, D.; Sauni, P. Importance and prospects of renewable energy: Emerging issues in India. Int. J. Art Humanit. Sci. 2015, 2, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad, U. The need for renewable energy sources. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Electr. Eng. 2015, 4, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, S.; Ganguly, S. Opportunities, barriers and issues with renewable energy development–A discussion. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 69, 1170–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.G.; Hall, C.A.; Balogh, S.; Gupta, A.; Arnold, M. Energy, EROI and quality of life. Energy Policy 2014, 64, 153–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sen, S.; Ganguly, S.; Das, A.; Sen, J.; Dey, S. Renewable energy scenario in India: Opportunities and challenges. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2016, 122, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorollahi, Y.; Yousefi, H.; Mohammadi, M. Multi-criteria decision support system for wind farm site selection using GIS. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2016, 13, 38–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edomah, N.; Ndulue, G. Energy transition in a lockdown: An analysis of the impact of COVID-19 on changes in electricity demand in Lagos Nigeria. Glob. Transit. 2020, 2, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, G.; Stone, A.; Hughes, A.; Stewart, T. Towards the Development of an Energy-Water-Food Security Nexus Based Modelling Framework as a Policy and Planning Tool for South Africa; University of Cape Town: Cape Town, South Africa, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA. REmap 2030: A Renewable Energy Roadmap; Dhabi, A., Ed.; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA. Rethinking Energy; Dhabi, A., Ed.; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Koivisto, M.; Gea-Bermúdez, J.; Kanellas, P.; Das, K.; Sørensen, P. North Sea region energy system towards 2050: Integrated offshore grid and sector coupling drive offshore wind power installations. Wind Energy Sci. 2020, 5, 1705–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, S.; Dinçer, H.; Uluer, G. The Role of Technological Development on Renewable Energy Usage: An Econometric Analysis for G7 Countries. In Handbook of Research on Sustainable Supply Chain Management for the Global Economy; Akkucuk, U., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 136–153. [Google Scholar]

- WWEA. World Wind Energy Association, World Wind Energy Association. 2014. Available online: https://wwindea.org/ (accessed on 26 February 2019).

- CWEA. Statistics of Chinese Installed Wind Power Generation Capacity 2018; Chinese Wind Energy Association: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- WWE Association. World Wind Energy Association, 25 February 2019. Available online: https://library.wwindea.org (accessed on 28 December 2019).

- SWEA. 100 Percent Renewable Electricity by 2040 Wind Power: Combating Climate Change; Swedish Wind Energy Association: Stockholm, Sweden, 2019; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Saidur, R.; Rahim, N.; Islam, M.; Solangi, K. Environmental impact of wind energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 2423–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyal, S.H.; Mortberg, U.; Mentis, D.; Welsch, M.; Babelon, I.; Howells, M. Wind energy assessment considering geographic and environmental restrictions in Sweden: A GIS-based approach. Energy 2015, 83, 447–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szurek, M.; Blachowski, J.; Nowacka, A. GIS-Based Method For Wind Farm Location Multi-Criteria Analysis. Min. Sci. 2014, 21, 65–81. [Google Scholar]

- Loring, J.M. Wind energy planning in England, Wales and Denmark: Factors influencing project success. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 2648–2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinne, E.; Holttinen, H.; Kiviluoma, J.; Rissanen, S. Effects of turbine technology and land use on wind power resource potential. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villacreses, G.; Gaona, G.; Martínez-Gomez, J.; Jijon, D.J. Wind Farms Suitability Location Using Geographical Information System (GIS), Based on Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) Methods: The Case of Continental Ecuador. Renew. Energy 2017, 109, 275–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.J.; Hudson, M.D. Regional Scale wind farm and solar farm suitability assessment using GIS-assisted multi-criteria evaluation. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 138, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggi, F.; Firmino, A.; Amado, M. Moving Forward on Sustainable Energy Transitions: The Smart Rural Model. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 4, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggi, F.; Firmino, A.; Amado, M. Planning renewable energy in rural areas: Impacts on occupation and land use. Energy 2018, 155, 630–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaddah, A.A.; Abdelwahed, M.F. GIS-based site-suitability modeling for seismic stations: Case study of the northern Rahat volcanic field, Saudi Arabia. Comput. Geosci. 2015, 83, 193–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latinopoulos, D.; Kechagia, K. A GIS-based multi-criteria evaluation for wind farm site selection. A regional scale application in Greece. Renew. Energy 2015, 78, 550–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krarti, M.; Dubey, K.; Howarth, N. Towards energy landscapes–Pathfinder for sustainable wind power locations. Energy 2017, 134, 611–621. [Google Scholar]

- Haaren, R.V.; Fthenakis, V. GIS-based wind farm site selection using spatial multi-criteria analysis (SMCA): Evaluating the Case For New York State. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 3332–3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamanehpour, E. Site Selection of Wind Power Plant Using Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Methods in GIS: A Case Study. Comput. Ecol. Softw. 2017, 7, 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Effat, H.A. Spatial Modeling of Optimum Zones for Wind Farms Using Remote Sensing and Geographic Information System, Application in the Red Sea, Egypt. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 2014, 6, 358–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Janke, J.R. Multicriteria GIS modeling of wind and solar farms in Colorado. Renew. Energy 2010, 35, 2228–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Yahyai, S.; Charabi, Y.; Gastli, A.; Al-Badi, A. Wind Farm Land Suitability Indexing Using Multi-Criteria Analysis. Renew. Energy 2012, 44, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Taweekun, J.; Techato, K.; Waewsak, J.; Gyawali, S. GIS based site suitability assessment for wind and solar farms in Songkhla, Thailand. Renew. Energy 2019, 132, 1360–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagreh, Y.; Bataineh, A. Renewable energy potential assessment in Jordan. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 2232–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GWA. Global Wind Atlas, DTU powered by WAsP. 2019. Available online: https://globalwindatlas.info/ (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- DOS. Population Projections for the Kingdom’s Residents during the Period 2015–2050; Jordan Department of Statistics: Amman, Jordan, 2016.

- Al-Addous, M.; Jaradat, M.; Albatayneh, A.; Wellmann, J. The Significance of Wind Turbines Layout Optimization on the Predicted Farm Energy Yield. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources. 2018. Available online: http://memr.gov.jo/Default.aspx (accessed on 16 April 2021).

- BP. Statistical Review of World Energy; British Petroleum: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Farooq, M.U.; Mahmood, A.; Sidhu, G.A.S.; Ullah, M.N.; Khan, Z.A. Wind Power and Smart Grid as an Environmental Obligation in Context of Energy Security for Pakistan. J. Basic Appl. Sci. Res. 2013, 9, 518–527. [Google Scholar]

- NEPCO. Annual Report; National Electric Power Company: Amman, Jordan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- NEPCO. National Electrical Power Company, May 2019. Available online: http://www.nepco.com.jo/en/Default_en.aspx (accessed on 17 April 2019).

- Abu-Rumman, G.K.A.; Khdair, S. Current status and future investment potential in renewable energy in Jordan: An overview. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WB. The World Bank. 2019. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/ (accessed on 10 March 2021).

- Kandah, A. The Impact of Public Debt on Economic Growth in Jordan; The Jordan Times: Amman, Jordan, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- TE. Jordan GDP Annual Growth Rate; Trading Economics: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L. How to make a decision: The analytic hierarchy process. Interfaces 1994, 24, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bennui, A.; Rattanamanee, P.; Puetpaiboon, U.; Phukpattaranont, P.; Chetpattananondh, K. Site Selection for Large Wind Turbine Using GIS. In Proceedings of the PSU-UNS International Conference on Engineering and Environment, Phuket, Thailand, 10 May 2007; pp. 561–566. [Google Scholar]

- Jahangiri, M.; Ghaderi, R.; Haghani, A.; Nematollahi, O. Finding the best locations for establishment of solar-wind power stations in Middle-East using GIS: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 66, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirdelen, T.; Ekinci, F.; Mert, B.; Karasu, İ.; Tümay, M. Green touch for hydrogen production via alkaline electrolysis: The semi-flexible PV panels mounted wind turbine design, production and performance analysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 10680–10695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Sun, X.; Huang, D. Aerodynamics of vertical-axis wind turbine with boundary layer suction–Effects of suction momentum. Energy 2020, 209, 118446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liserre, M.; Cárdenas, R.; Molinas, M. Overview of multi-MW wind turbines and wind parks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2011, 58, 1081–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourrajabian, A.; Mirzaei, M.; Ebrahimi, R.; Wood, D. Effect of air density on the performance of a small wind turbine blade: A case study in Iran. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2014, 126, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.; Bhattacharya, S. Vibrations of wind-turbines considering soil-structure interaction. Wind Struct. 2011, 14, 85–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El-Moghrabi, L.; Masri, I. Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) for Shobak 45 MW Wind Power Project in Ma’an; ECO Consult: Amman, Jordan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Heras, J.; Martín, M. Social issues in the energy transition: Effect on the design of the new power system. Appl. Energy 2020, 278, 115654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharaibeh, A.A.; Shaamala, A.H.; Ali, M.H. Multi-Criteria Evaluation for Sustainable Urban Growth in An-Nuayyimah, Jordan; Post War Study. Procedia Manuf. 2020, 44, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaradat, R.A.; Nusier, O.K.; Awawdeh, M.M.; Al-Qaryouti, M.Y.; Fahjan, Y.M.; Al-Rawabdeh, A.M. Deaggregation of Probabilistic Ground Motions for Selected Jordanian Cities. Jordan J. Civ. Eng. 2008, 2, 172–196. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, J.; Liu, J.N.K.; Ngai, E.W.T. Application of decision-making techniques in supplier selection: A systematic review of literature. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 3872–3885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, J. AHP-express: A simplified version of the analytical hierarchy process method. MethodsX 2020, 7, 100748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lantz, E.J.; Roberts, J.O.; Nunemaker, J.; DeMeo, E.; Dykes, K.L.; Scott, G.N. Increasing Wind Turbine Tower Heights: Opportunities and Challenge; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2019.

- Giani, P.; Tagle, F.; Genton, M.G.; Castruccio, S.; Crippa, P. Closing the gap between wind energy targets and implementation for emerging countries. Appl. Energy 2020, 269, 115085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Masri, H.M.; AbuElrub, A.; Ehsani, M. Optimization and Layout of a Wind Farm Connected to a Power Distribution System. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Technology (ICIT), Lyon, France, 20 February 2018; pp. 1049–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Soud, M. Assessment of wind characteristics and wind potential energy yield in the Jordanian southern region. J. Energy Power Eng. 2015, 9, 348–357. [Google Scholar]

- Hamzeh, A.; Awad, M. Wind power generation in Jordan: Current situation and future plans. In The Age of Wind Energy. Innovative Renewable Energy; Milborrow, A.S.a.D., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA. Future of Wind: Deployment, Investment, Technology, Grid Integration, and Socioeconomic Aspects (A Global Energy Transformation Paper); Dhabi, A., Ed.; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, L.; Hoistad, C.; Turner, D. WINDUSTRY. 2019. Available online: http://www.windustry.org (accessed on 13 April 2019).

- PSC. Shobak 45MW Wind Power Project, Shobak Wind Energy; Jordan Wind Project Company PSC: Amman, Jordan, 2017.

- The National Renewable Energy Laboratory. NREL Transforming Energy. 2018. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/ (accessed on 13 April 2019).

- NWW. National Wind Watch, National Wind Watch. Available online: https://www.windpowerengineering.com/windpower-profitability-and-break-even-point-calculations/ (accessed on 10 April 2021).

- Solar Reviews. 2019. Available online: https://www.solarreviews.com/ (accessed on 28 May 2019).

- Tafarte, P.; Kanngießer, A.; Dotzauer, M.; Meyer, B.; Grevé, A.; Millinger, M. Interaction of electrical energy storage, flexible bioenergy plants and system-friendly renewables in wind-or solar PV-dominated regions. Energies 2020, 13, 1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weinstein, M. Future Scenarios for Energy Security and Sustainable Desalination in Jordan. Master’s Thesis, KTH School of Industrial Engineering and Management, Stockholm, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, H.; Xu, T.; Wu, X.; Wang, H.; Tang, A.; Chen, Y. Optimal capacity configuration of the wind-photovoltaic-storage hybrid power system based on gravity energy storage system. Appl. Energy 2020, 271, 115052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 11 countries leading the charge on renewable Energy. 2021. Available online: https://www.climatecouncil.org.au/11-countries-leading-the-charge-on-renewable-energy/ (accessed on 21 March 2021).

- Saraswat, S.; Digalwar, A.; Yadav, S.; Kumar, G. MCDM and GIS based modelling technique for assessment of solar and wind farm locations in India. Renew. Energy 2021, 169, 865–884. [Google Scholar]

- Ryberg, D.; Tulemat, Z.; Stolten, D.; Robinius, M. Uniformly constrained land eligibility for onshore European wind power. Renew. Energy 2020, 146, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, S.; Rodrigues, T.; Chagas, A. The impact of wind power on the Brazilian labor market. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 128, 109887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, A.; Hanley, N.; Wright, R. Valuing the attributes of renewable energy investments. Energy Pol. 2006, 34, 1004–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Munday, M. Capital ownership, innovation and regional development policy in the economic periphery: An energy industry case. Local Econ. 2020, 35, 545–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, S.; Sovacool, B. Rethinking the future low-carbon city: Carbon neutrality, green design, and sustainability tensions in the making of Masdar City. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 62, 101368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsisi, M.; Tran, M.; Mahmoud, K.; Lehtonen, M.; Darwish, M. Robust Design of ANFIS-Based Blade Pitch Controller for Wind Energy Conversion Systems Against Wind Speed Fluctuations. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 37894–37904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharaibeh, A.A.; Jaradat, R.A.; Okour, Y.F.; Al-Rawabdeh, A.M. Landscape Perception and Landscape Change for the City of Irbid, Jordan. J. Archit. Plan. 2017, 29, 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Tazay, A.F.; Ibrahim, A.M.A.; Noureldeen, O.; Hamdan, I. Modeling, control, and performance evaluation of grid-tied hybrid PV/wind power generation system: Case study of Gabel El-Zeit region, Egypt. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 96528–96542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, P.; McKeogh, E.; Murphy, J.; Cummins, V. Development of a viability assessment model for hydrogen production from dedicated offshore wind farms. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, A.; Firestone, J.; Bidwell, D.; Gardner, M. Place meaning and consistency with offshore wind: An island and coastal tale. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 132, 110044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohe, S. The regional facet of a global innovation system: Exploring the spatiality of resource formation in the value chain for onshore wind energy. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2020, 36, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Criteria | Sub-Criteria | Data (Unsuitable Areas) |

|---|---|---|

| Land-use/Landcover | Environmental preservations | Area in distance < 2000 m |

| Proximity to urban areas | Area in distance < 2000 m | |

| Proximity to water bodies | Area in distance < 1000 m | |

| Proximity to forest | Area in distance < 2000 m | |

| Quarries | Area in distance < 200 m | |

| Proximity to commercial airports | Area in distance < 2500 m | |

| Proximity to military airports | Area in distance < 15,000 m |

| Criteria | Suitability Scores (0 Is Unsuitable and 5 Is Most Suitable) and Weigh Values for Each Criterion | Factors Weights * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| Proximity to Roads | <500 m | >8001 m | 6001–8000 m | 4001–6000 m | 2001–4000 m | 501–2000 m | 15 |

| Proximity to Railway | <250 m | - | - | - | - | >250 m | 5 |

| Proximity to Electrical Power Lines | <250 m | >8001 m | 6001–8000 m | 4001–6000 m | 2001–4000 m | 250–2000 m | 10 |

| Slope | >15° | 10.1–15° | - | 5.1–10° | - | 0–5° | 10 |

| Aspect | S-W | S, E-S | - | E, E-N | - | N, N-W, W, Flat | 5 |

| Wind Speed | <5 m/s | 5–6 m/s | 6–7 m/s | 7–8 m/s | 8–9 m/s | >9 m/s | 30 |

| Wind Power Density | <200 W/M | 201–400 W/M | 401–600 W/M | 601–800 W/M | 801–1000 W/M | >1000 W/M | 20 |

| Proximity to faults ** | 0.61–0.7 g | 0.51–0.6 g | 0.41–0.5 g | 0.31–0.4 g | 0.21–0.3 g | 0.11–0.2 g | 5 |

| Total | 100% | ||||||

| Hub Height (m) | High Suitable Areas (km2) | Rotor Diameter, D (m) | Equation * | Area For each Turbine (km2) | Number of Turbines Required to Cover all Needs of Jordan | Installation Area (km2) | Remaining Area (km2) | AEP Total (kWh/year) | The Annual Profit (Billion $ USD) | Total Cost Estimation (Billion $ USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| =6D × 10D ** | =Jordan’s Electrical Annual Energy Consumption/Annual Energy Production for Each Turbine | =Number of Turbine × Area Required for Each Turbine | =High Suitable Area—Total Area Required for Turbines | =Number of Turbines × AEP for Each Turbine. | =Number of Turbines × Annual Profit (Pa) for Each Turbine | =Number of Turbines × Cost of Each Turbine | ||||

| 50 | 2349.0 | 50 | 0.15 | 5709 | 856.35 | 1492.65 | 17,503,794,000 | $1.348 | $7.422 | |

| 100 | 6768.2 | 100 | 0.60 | 2854 | 1712.4 | 5055.8 | 17,500,728,000 | $1.313 | $8.562 | |

| 200 | 13,251.8 | 150 | 1.35 | 1654 | 2232.9 | 11,018.9 | 17,495,515,800 | $1.417 | $6.616 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gharaibeh, A.A.; Al-Shboul, D.A.; Al-Rawabdeh, A.M.; Jaradat, R.A. Establishing Regional Power Sustainability and Feasibility Using Wind Farm Land-Use Optimization. Land 2021, 10, 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10050442

Gharaibeh AA, Al-Shboul DA, Al-Rawabdeh AM, Jaradat RA. Establishing Regional Power Sustainability and Feasibility Using Wind Farm Land-Use Optimization. Land. 2021; 10(5):442. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10050442

Chicago/Turabian StyleGharaibeh, Anne A., Deema A. Al-Shboul, Abdulla M. Al-Rawabdeh, and Rasheed A. Jaradat. 2021. "Establishing Regional Power Sustainability and Feasibility Using Wind Farm Land-Use Optimization" Land 10, no. 5: 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10050442

APA StyleGharaibeh, A. A., Al-Shboul, D. A., Al-Rawabdeh, A. M., & Jaradat, R. A. (2021). Establishing Regional Power Sustainability and Feasibility Using Wind Farm Land-Use Optimization. Land, 10(5), 442. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10050442