Land Abandonment in Mountain Areas of the EU: An Inevitable Side Effect of Farming Modernization and Neglected Threat to Sustainable Land Use

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Gaps in land rent between settlement areas and agricultural areas are so high that economic valorization stimulates the conversion of agricultural land into artificial land use. Urbanization and urban sprawl are not restricted to agglomeration areas but reduce UAA, also within rural regions.

- On the other hand, UAA is converted into forests. Such land-change processes are observed primarily for areas where agriculture is economically challenged, and afforestation may be part of an agricultural extensification strategy.

- Beyond those two, clear-cut trends of general land-use change, productivity increases and changes in regional competitiveness of agricultural production might lead to gradual adaptation in the production structure, and spatial concentration of production. As a result, agricultural land use of some farmland might be ceased, depending on a series of local and individual factors.

2. Materials and Methods

3. Elevated Risk of Land Abandonment in Mountain Regions

3.1. Risk Assessment in Mountain Regions of the EU

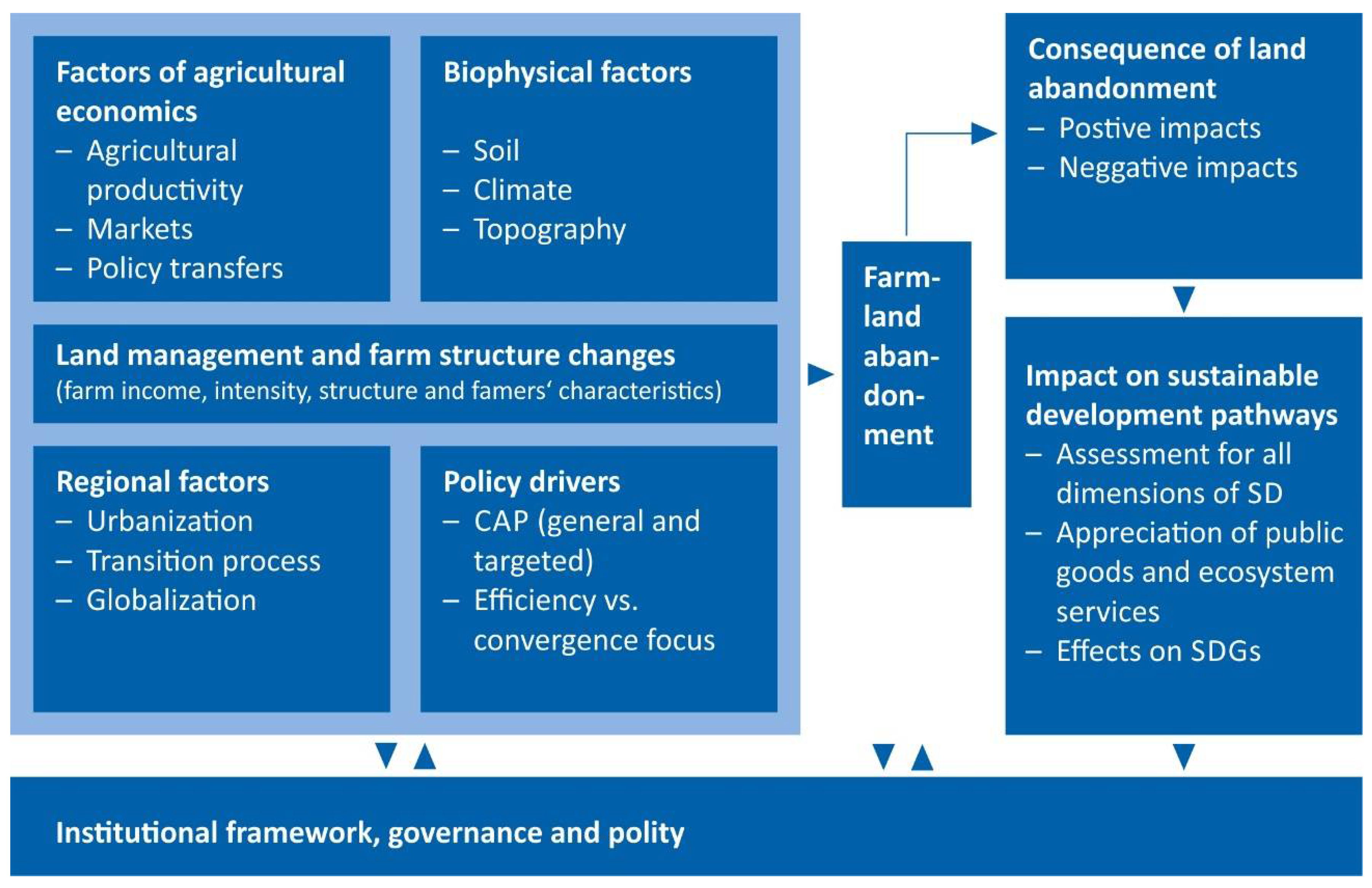

3.2. Drivers and Policy Framework to Respond to Land Abandonment Challenges in Mountain Areas

4. Discussion

- -

- The large variety of causes for land abandonment across European regions and the methodological complexity in assessing land\-use changes and status blur the common and large-scale triggers for long-term underlying trends. Scale aspects and the multitude of drivers contribute to a simplified understanding of areas taken out of management [9,65].

- -

- Although an increased attention to local assets and opportunities of remote and mountain regions is visible, myths about causes are still predominant [62]. These relate particularly to overly generalized views on focusing on the present land use (path-dependency), role of forest areas, urbanization processes and globalization as a unifying, but undervalued aspect.

- -

- Processes of land abandonment, natural successional transition and marginalization in remote regions of Europe lead to a decline in pastures, grassland, and arable habitats as well as an increase in scrub and forests. This implies pressures on high nature value (HNV) farmlands, loss of biodiversity and viability of farm units in these areas [66].

- -

- -

- Land management in mountain areas is key for providing important ecosystem services for local and trans-regional demand [26]. These functions are represented in public discourse often as public goods [68,69], the specific shaping of features of landscapes and landscape development [47,70,71,72], securing heritage features of cultural landscapes [73] and the diversity of habitats and biodiversity, thus ensuring place-specific nature contributions to society [74,75].

- -

- While there might also be some benefits from land abandonment due to species re-establishment and the development of new habitat mosaics in mountain regions [16,67], several studies assess that a decline in habitat heterogeneity and species diversity across mountain landscapes is predominant [9,65,67]. This is due to the fact that species that benefit from land abandonment are often generalist species of low biodiversity value [76].

- -

- Beyond human-nature relationships, land abandonment in mountain areas is contingent on issues of location (accessibility), cultural heritage and social preference. In particular, prospects for regional performance and transnational perspectives on functions of land use are of decisive influence [77,78].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maréchal, A.; Hart, K.; Baldock, D.; Erjavec, E.; Rac, I.; Vanni, F.; Mantino, F. Policy Lessons and Recommendations from the PEGASUS Project; Deliverable 5.4. H2020-Project Public Ecosystem Goods and Services from Land Management—Unlocking the Synergies; Grant No. 633814; IEEP: London, UK, 2018; Available online: http://pegasus.ieep.eu/system/resources/W1siZiIsIjIwMTgvMDMvMDEvMWVodjMwdmhzaV9ENS40X1BvbGljeV9sZXNzb25zX2FuZF9yZWNvbW1lbmRhdGlvbnNfRklOQUwucGRmIl1d/D5.4%20-%20Policy%20lessons%20and%20recommendations%20FINAL.pdf?sha=4a285dbdf37d756d (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Pointereau, P.; Coulon, F.; Girard, P.; Lambotte, M.; Stuczynski, T.; Sánchez Ortega, V.; Del Rio, A. Analysis of Farmland Abandonment and the Extent and Location of Agricultural Areas that are Actually Abandoned or are in Risk to be Abandoned. In JRC Scientific and Technical Reports; European Commission, Joint Research Centre, Institute for Environment and Sustainability: Ispra, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Van Leeuwen, E.S.; Strijker, D.; Terluin, I. Regional Concentration and Specialisation in Agricultural Activities in EU-9 Regions (1950–2000). Eur. Spat. Res. Policy 2010, 17, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vesco, P.; Kovacic, M.; Mistry, M.; Croicu, M. Climate variability, crop and conflict: Exploring the impacts of spatial concentration in agricultural production. J. Peace Res. 2021, 58, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, W. The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture; Counterpoint: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Dax, T.; Hellegers, P. Policies for Less-Favoured Areas. In CAP Regimes and the European Countryside, Prospects for Integration between Agricultural, Regional and Environmental Policies; Brouwer, F., Lowe, P., Eds.; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 2000; pp. 179–197. [Google Scholar]

- Baldock, D.; Beaufoy, G.; Brouwer, F.; Godeschalk, F. Farming at the Margins: Abandonment or Redeployment of Agricultural Land in Europe; Institute for European Environmental Policy (IEEP): London, UK; Agricultural Economics Research Institute (LEI-DLO): Hague, The Netherlands, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree, R.; MacDonald, D.; Hanley, N. Non-Market Benefits Associated with Mountain Regions. In Report for Highlands and Islands Enterprise and Scottish Natural Heritage; CJC Consulting: Aberdeen, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Keenleyside, C.; Tucker, G.M. Farmland Abandonment in the EU: An Assessment of Trends and Prospects. In Report Prepared for WWF; Institute for European Environmental Policy: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Cultivating Rural Amenities, An Economic Development Perspective; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, M.R.; Kuemmerle, T.; Müller, D.; Erb, K.; Verburg, P.H.; Haberl, H.; Vesterager, V.P.; Andrič, M.; Antrop, M.; Austrheim, G.; et al. Transitions in European land-management regimes between 1800 and 2010. Land Use Policy 2015, 49, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perpiña Castillo, C.; Kavalov, B.; Diogo, V.; Jacobs-Crisioni, C.; Batista e Silva, F.; Lavalle, C. Agricultural Land Abandonment in the EU within 2015–2030. In JRC Report 113718; European Commission: Ispra, Italy, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke, E. Drivers of Land Abandonment in the Irish Uplands: A Case Study. Eur. Countrys. 2019, 11, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ustaoglo, E.; Collier, M.J. Farmland abandonment in Europe: An overview of drivers, consequences and assessment of the sustainability implications. Environ. Rev. 2018, 26, 396–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasanta, T.; Arnáez, J.; Pascual, N.; Ruiz-Flaño, P.; Errea, M.P.; Lana-Renault, N. Space-time process and drivers of land abandonment in Europe. Catena 2017, 149, 810–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benayas, J.M.; Martins, A.; Nicolau, J.M.; Schulz, J.J. Abandonment of agricultural land: An overview of drivers and consequences. Cab Rev. Perspect. Agric. Vet. Sci. Nutr. Nat. Resour. 2007, 2, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chaudhary, S.; Wang, Y.; Dixit, A.M.; Khanal, N.R.; Xu, P.; Fu, B.; Yan, K.; Liu, Q.; Lu, Y.; Li, M. A Synopsis of Farmland Abandonment and Its Driving Factors in Nepal. Land 2020, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kristensen, S.B.P.; Busck, A.G.; van der Sluis, T.; Gaube, V. Patterns and drivers of farm-level land use change in selected European rural landscapes. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 786–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/FAO/UNCDF. Adopting a Territorial Approach to Food Security and Nutrition Policy; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Coordination Via Campesina (ECVC). Food Sovereignty Now! A guide to Food Sovereignty; ECVC: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Levkoe, C.Z.; Brem-Wilson, J.; Anderson, C.R. People, power, change: Three pillars of a food sovereignty research praxis. J. Peasant Stud. 2019, 46, 1389–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuh, B.; Dax, T.; Andronic, C.; Derszniak-Noirjean, M.; Gaupp-Berghausen, M.; Hsiung, C.-H.; Münch, A.; Machold, I.; Schroll, K.; Brkanovic, S. The Challenge of Land Abandonment after 2020 and Options for Mitigating Measures. In Research for AGRI-Committee; European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, Directorate-General for Internal Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://bit.ly/39ElcFJ (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Prishchepov, A.V.; Schierhorn, F.; Löw, F. Unraveling the Diversity of Trajectories and Drivers of Global Agricultural Land Abandonment. Land 2021, 10, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plieninger, P.; Draux, T.; Fagerholm, H.; Bieling, N.; Burgi, C.; Kizos, M.T. The driving forces of landscape change in Europe: A systematic review of the evidence. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klein, J.A.; Tucker, C.M.; Nolin, A.W.; Hopping, K.A.; Reid, R.S.; Steger, C.; Grêt-Regamey, A.; Lavorel, S.; Müller, B.; Yeh, E.T.; et al. Catalyzing transformations to sustainability in the world’s mountains. Earths Future 2019, 7, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grêt-Regamey, A.; Brunner, S.H.; Kienast, F. Mountain ecosystem services: Who cares? Mt. Res. Dev. 2012, 32, S23–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, D.; Crabtree, J.R.; Wiesinger, G.; Dax, T.; Stamou, N.; Fleury, P.; Gutierrez Lazpita, J.; Gibon, A. Agricultural abandonment in mountain areas of Europe: Environmental consequences and policy response. J. Environ. Manag. 2000, 59, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santini, F.; Guri, F.; Gomez y Paloma, S. Labelling of Agricultural and Food Products of Mountain Farming. In JRC Working Papers JRC77119; Joint Research Centre: Sevilla, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bentivoglio, D.; Savini, S.; Finco, A.; Bucci, G.; Boselli, E. Quality and origin of mountain food products: The new European label as a strategy for sustainable development. J. Mt. Sci. 2019, 16, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.M.; Kansal, A. Integrating value-chain approach with participatory multi-criteria analysis for sustainable planning of a niche crop in Indian Himalayas. J. Mt. Sci. 2019, 16, 2417–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, F.; van Rheenen, T.; Dhillion, S.S.; Elgersma, A.M. (Eds.) Sustainable Land Management, Strategies to Cope with the Marginalisation of Agriculture; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Copus, A.; Kahila, P.; Fritsch, M.; Dax, T.; Kovacs, K.; Tagai, G.; Weber, R.; Grunfelder, J.; Löfving, L.; Moodie, J.; et al. Final Report. European Shrinking Rural Areas: Challenges, Actions and Perspectives for Territorial Governance; ESPON 2020 project ESCAPE; Version 21/12/2020; ESPON EGTC: Luxembourg, 2020; Available online: https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/ESPON%20ESCAPE%20Main%20Final%20Report.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Dax, T.; Copus, A. The Future of Rural Development. In Research for AGRI Committee—CAP Reform Post-2020—Challenges in Agriculture, Workshop Documentation; European Parliament, Directorate-General for Internal Policies, Ed.; Report IP/B/AGRI/IC/2015-195; Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies, Agriculture and Rural Development: Brussels, Belgium, 2016; pp. 221–303. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2016/585898/IPOL_STU(2016)585898_EN.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Payne, D.; Snethlage, M.; Geschke, J.; Spehn, E.M.; Fischer, M. Nature and People in the Andes, East African Mountains, European Alps, and Hindu Kush Himalaya: Current Research and Future Directions. Mt. Res. Dev. 2020, 40, A1–A14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitti, A.; Nagai, M.; Dailey, M.; Ninsawat, S. Exploring Land Use and Land Cover of Geotagged Social-Sensing Images Using Naive Bayes Classifier. Sustainability 2016, 8, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pe’er, G.; Bonn, A.; Bruelheide, H.; Dieker, P.; Eisenhauer, N.; Feindt, P.H.; Hagedorn, G.; Hansjürgens, B.; Herzon, I.; Lomba, A.; et al. Action needed for the EU Common Agricultural Policy to address sustainability challenges. People Nat. 2020, 2, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, A.; Lefebvre, O.; Balogh, L.; Barberi, P.; Batello, C.; Bellon, S.; Gaifami, T.; Gkisakis, V.; Lana, M.; Migliorini, P.; et al. A Green Deal for implementing agroecological systems: Reforming the Common Agricultural Policy of the European Union. J. Sustain. Org. Agric. Syst. 2020, 70, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Environment Agency (EEA). Landscapes in Transition, An Account of 25 Years of Land Cover Change in Europe; EEA Report No 10/2017; EEA: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gellrich, M.; Zimmermann, N.E. Investigating the regional-scale pattern of agricultural land abandonment in the Swiss mountains: A spatial statistical modelling approach. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 2007, 79, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuemmerle, T.; Levers, C.; Erb, K.; Estel, S.; Jepsen, M.R.; Müller, D.; Plutzar, C.; Stürck, J.; Verkerk, P.J.; Verburg, P.H.; et al. Hotspots of land use change in Europe. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissteiner, C.J.; Boschetti, M.; Böttcher, K.; Carrara, P.; Bordogna, G.; Brivio, P.A. Spatial explicit assessment of rural land abandonment in the Mediterranean area. Glob. Planet. Chang. 2011, 79, 20–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estel, S.; Kuemmerle, T.; Alcántara, C.; Levers, C.; Prishchepov, A.; Hostert, P. Mapping farmland abandonment and recultivation across Europe using MODIS NDVI time series. Remote Sens. Environ. 2015, 163, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.A.; Schermer, M.; Stotten, R. The resilience and vulnerability of remote mountain communities: The case of Vent, Austrian Alps. Land Use Policy 2018, 71, 372–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flury, C.; Huber, R.; Tasser, E. Future of Mountain Agriculture in the Alps. In The Future of Mountain Agriculture; Mann, S., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddaway, N.R.; Styles, D.; Pullin, A.S. Evidence on the environmental impacts of farm land abandonment in high altitude/mountain regions: A systematic map. Environ. Evid. 2014, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beilin, R.; Lindborg, R.; Stenseke, M.; Pereira, H.M.; Llausàs, A.; Slätmo, E.; Cerqueira, Y.; Navarro, L.; Rodrigues, P.; Reichelt, N.; et al. Analysing how drivers of agricultural land abandonment affect biodiversity and cultural landscapes using case studies from Scandinavia, Iberia and Oceania. Land Use Policy 2014, 36, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martín, M.; Quintas-Soriano, C.; Torralba, M.; Wolpert, F.; Plieninger, T. Landscape Change in Europe; Chapter 2. In Sustainable Land Management in a European Context, Human-Environment Interactions 8. Cham; Weith, T., Bartkmann, T., Gaasch, N., Rogga, S., Strauß, C., Zscheischler, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar]

- Massot, A.; Nègre, F. Research for AGRI Committee—The upcoming Commission’s Communication on the Long-Term Vision of Rural Areas: Context and Preliminary Analysis; European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Terres, J.M.; Nisini Scacchiafichi, L.; Wania, A.; Ambar, M.; Anguiano, E.; Buckwell, A.; Coppola, A.; Gocht, A.; Nordstrom Kallstrom, A.; Pointereau, P.; et al. Farmland abandonment in Europe: Identification of drivers and indicators, and development of a composite indicator of risk. Land Use Policy 2015, 49, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.L.; Mandel, M.; Al-Amin, A.Q.; Feher, A.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C. An assessment of the causes and con-sequences of agricultural land abandonment in Europe. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2016, 24, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dax, T.; Wiesinger, G. Rural Amenities in Mountain Areas. In Sustainable Land Management, Strategies to Cope with the Marginalisation of Agriculture; Brouwer, F., van Rheenen, T., Dhillion, S.S., Elgersma, A.M., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 131–148. [Google Scholar]

- Zukauskaite, E.; Trippl, M.; Plechero, M. Institutional Thickness Revisited. Econ. Geogr. 2017, 93, 325–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorn, J.P.R.; Klein, J.A.; Steger, C.; Hopping, K.A.; Capitani, C.; Tucker, C.M.; Nolin, A.W.; Reid, R.S.; Chitale, V.S.; Marchant, R. A systematic review of participatory scenario planning to envision mountain socio-ecological systems futures. Ecol. Soc. 2020, 25, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavalloni, M.; D’Alberto, R.; Raggi, M.; Viaggi, D. Farmland abandonment, public goods and the CAP in a marginal area of Italy. Land Use Policy 2019, 104365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maréchal, A. A Step Change in Policy to Deliver More Environmental and Social Benefits. In Policy Brief; Final Conference 7 February, EU-Project PEGASUS; IEEP: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. (COM(2018)392), Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council Establishing Rules on Support for Strategic Plans to be Drawn Up by Member States under the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP Strategic Plans) and Financed by the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF) and by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) and Repealing Regulation (EU) No 1305/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Regulation (EU) No 1307/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree, R.; Dax, T.; Hovorka, G.; Köbler, M.; Delattre, F.; Vlahos, G.; Christopoulos, S.; Louloudis, L.; Viladomiu, L.; Rosell, J.; et al. Review of Area-based Less-Favoured Area Payments Across EU Member States. In Report for the Land Use Policy Group (LUPG) of the GB Statutory Conservation, Countryside and Environment Agencies, CJC Consulting; LUPG: Peterborough, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Van Orshoven, J.; Terres, J.-M.; Tóth, T. (Eds.) Updated Common Bio-Physical Criteria to Define Natural Constraints for Agriculture in Europe. In JRC Scientific and Technical Reports; JRC, Institute for Environment and Sustainability: Ispra, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Blue Marble Evaluation: Premises and Principles; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, A. Evaluation at the Nexus: Evaluating Sustainable Development in the 2020s. In Evaluating Environment in International Development, 2nd ed.; Uitto, J.I., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021; pp. 46–60. [Google Scholar]

- Dax, T.; Copus, A. Final Report—Annex 13 How to Achieve a Transformation Framework for Shrinking Rural Regions; European Shrinking Rural Areas: Challenges, Actions and Perspectives for Territorial Governance, ESPON 2020 Project ESCAPE; Version 21/12/2020; ESPON EGTC: Luxembourg, 2020; Available online: https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/ESPON%20ESCAPE%20Final%20Report%20Annex%2013%20-%20Transformation%20Framework.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Lambin, E.F.; Turner, B.L.; Geist, H.J.; Agbola, S.B.; Angelsen, A.; Bruce, J.W.; Coomes, O.T.; Dirzo, R.; Fischer, G.; Folke, C.; et al. The causes of land-use and land-cover change: Moving beyond the myths. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2001, 11, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission (EC). Peak Performance: New Insights into Mountain Farming in the European Union. In Commission Staff Working Document SEC(2009) 1724 Final; EC: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dolton-Thornton, N. Viewpoint: How should policy respond to land abandonment in Europe? Land Use Policy 2021, 102, 105269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, K.; Allen, B.; Lindner, M.; Keenleyside, C.; Burgess, P.; Eggers, J.; Buckwell, A. Land as an Environmental Resource. In Report Prepared for DG Environment, Contract No ENV.B.1/ETU/2011/0029; Institute for European Environmental Policy: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke, E.; Charbonneau, M.; Poinsot, Y. High nature value mountain farming systems in Europe: Case studies from the Atlantic Pyrenees, France and the Kerry Uplands, Ireland. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 46, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, H.M.; Navarro, L.M. (Eds.) Rewilding European Landscapes; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lefebvre, M.; Espinosa, M.; Gomez y Paloma, S.; Paracchini, M.L.; Piorr, A.; Zasada, I. Agricultural landscapes as multiscale public good and the role of the Common Agricultural Policy. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2015, 58, 2088–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nigmann, T.; Dax, T.; Hovorka, G. Applying a social-ecological approach to enhancing provision of public goods through agriculture and forestry activities across the European Union. Stud. Agric. Econ. 2018, 120, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarolli, P.; Straffelini, E. Agriculture in Hilly and Mountainous Landscapes: Threats, Monitoring and Sustainable Management. Geogr. Sustain. 2020, 1, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Sluis, T.; Pedroli, B.; Frederiksen, P.; Kristensen, S.B.P.; Gravsholt Busck, A.; Pavlis, V.; Cosor, G.L. The impact of European landscape transitions on the provision of landscape services: An explorative study using six cases of rural land change. Landsc. Ecol. 2019, 34, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van der Zanden, E.H.; Carvalho-Ribeiro, S.M.; Verburg, P.H. Abandonment landscapes: User attitudes, alternative futures and land management in Castro Laboreiro, Portugal. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2018, 18, 1509–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tarolli, P.; Preti, F.; Romano, N. Terraced landscapes: From an old best practice to a potential hazard for soil degradation due to land abandonment. Anthropocene 2014, 6, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, I.; Marull, J.; Tello, E.; Diana, G.L.; Pons, M.; Coll, F.; Boada, M. Land abandonment, landscape, and biodiversity: Questioning the restorative character of the forest transition in the Mediterranean. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martín-López, B.; Leister, I.; Cruz, P.L.; Palomo, I.; Grêt-Regamey, A.; Harrison, P.A.; Lavorel, S.; Locatelli, B.; Luque, S.; Walz, A. Nature’s contributions to people in mountains: A review. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- IEEP; Alterra. Reflecting Environmental Land Use Needs into EU Policy: Preserving and Enhancing the Environmental Benefits of “land Services”: Soil Sealing, Biodiversity Corridors, Intensification/Marginalisation of Land Use and Permanent Grassland. In Final Report to the European Commission, DG Environment on Contract ENV.B.1/ETU/2008/0030; Institute for European Environmental Policy: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferkorn, W.; Musović, Z. Analysing the Interrelationship between Regional Development and Cultural Landscape Change in the Alps. In Work Package 2 Report, REGALP; Regional Consulting: Wien, Austria, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schirpke, U.; Tappeiner, U.; Tasser, E. A transnational perspective of global and regional ecosystem service flows from and to mountain regions. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meeus, J.H.A.; Wijermans, M.P.; Vroom, M.J. Agricultural Landscapes in Europe and their Transformation. Landsc. Urban. Plan. 1990, 18, 289–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Zanden, E.H.; Verburg, P.H.; Schulp, C.J.E.; Verkerk, P.J. Trade-offs of European agricultural abandonment. Land Use Policy 2017, 62, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Share of Mountain Areas | Very High (>80%) | High (60–80%) | Moderate (40–60%) | Low (20–40%) | Very Low (<20%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk level(%) | |||||

| Very high | 0.545 | 0.0455 | 0.0455 | 0 | 0.364 |

| High | 0.511 | 0.145 | 0.046 | 0.015 | 0.282 |

| Moderate | 0.169 | 0.266 | 0.162 | 0.052 | 0.351 |

| Low | 0.012 | 0.055 | 0.210 | 0.232 | 0.491 |

| Very Low | 0.017 | 0.005 | 0.019 | 0.061 | 0.898 |

| Mountain Range | Medium Risk | High/Very High Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Alps | 42.7 | 46.6 |

| Apennines | 56.7 | 13.0 |

| Balkans/Southeast Europe | 34.0 | 29.3 |

| British Isles | 27.0 | 29.6 |

| Carpathians | 58.7 | 21.7 |

| Central European middle mountains 1 (BE + GE) | 35.9 | 3.0 1 |

| Central European middle mountains 2 (CZ; AT; GE) | 28.2 | 9.3 1 |

| Eastern Mediterranean islands | 41.8 | 58.2 1 |

| French/Swiss middle mountains | 26.7 | 17.9 |

| Iberian mountains | 46.4 | 16.1 |

| Nordic mountains | 49.6 | 5.7 1 |

| Pyrenees | 39.2 | 14.8 1 |

| Western Mediterranean islands | 67.5 | 13.5 1 |

| Mountain areas (EU-28) | 42.9 | 20.5 |

| Non-mountain areas (EU-28) | 21.8 | 7.7 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dax, T.; Schroll, K.; Machold, I.; Derszniak-Noirjean, M.; Schuh, B.; Gaupp-Berghausen, M. Land Abandonment in Mountain Areas of the EU: An Inevitable Side Effect of Farming Modernization and Neglected Threat to Sustainable Land Use. Land 2021, 10, 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10060591

Dax T, Schroll K, Machold I, Derszniak-Noirjean M, Schuh B, Gaupp-Berghausen M. Land Abandonment in Mountain Areas of the EU: An Inevitable Side Effect of Farming Modernization and Neglected Threat to Sustainable Land Use. Land. 2021; 10(6):591. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10060591

Chicago/Turabian StyleDax, Thomas, Karin Schroll, Ingrid Machold, Martyna Derszniak-Noirjean, Bernd Schuh, and Mailin Gaupp-Berghausen. 2021. "Land Abandonment in Mountain Areas of the EU: An Inevitable Side Effect of Farming Modernization and Neglected Threat to Sustainable Land Use" Land 10, no. 6: 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10060591

APA StyleDax, T., Schroll, K., Machold, I., Derszniak-Noirjean, M., Schuh, B., & Gaupp-Berghausen, M. (2021). Land Abandonment in Mountain Areas of the EU: An Inevitable Side Effect of Farming Modernization and Neglected Threat to Sustainable Land Use. Land, 10(6), 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10060591