The Economic Role and Emergence of Professional Valuers in Real Estate Markets

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

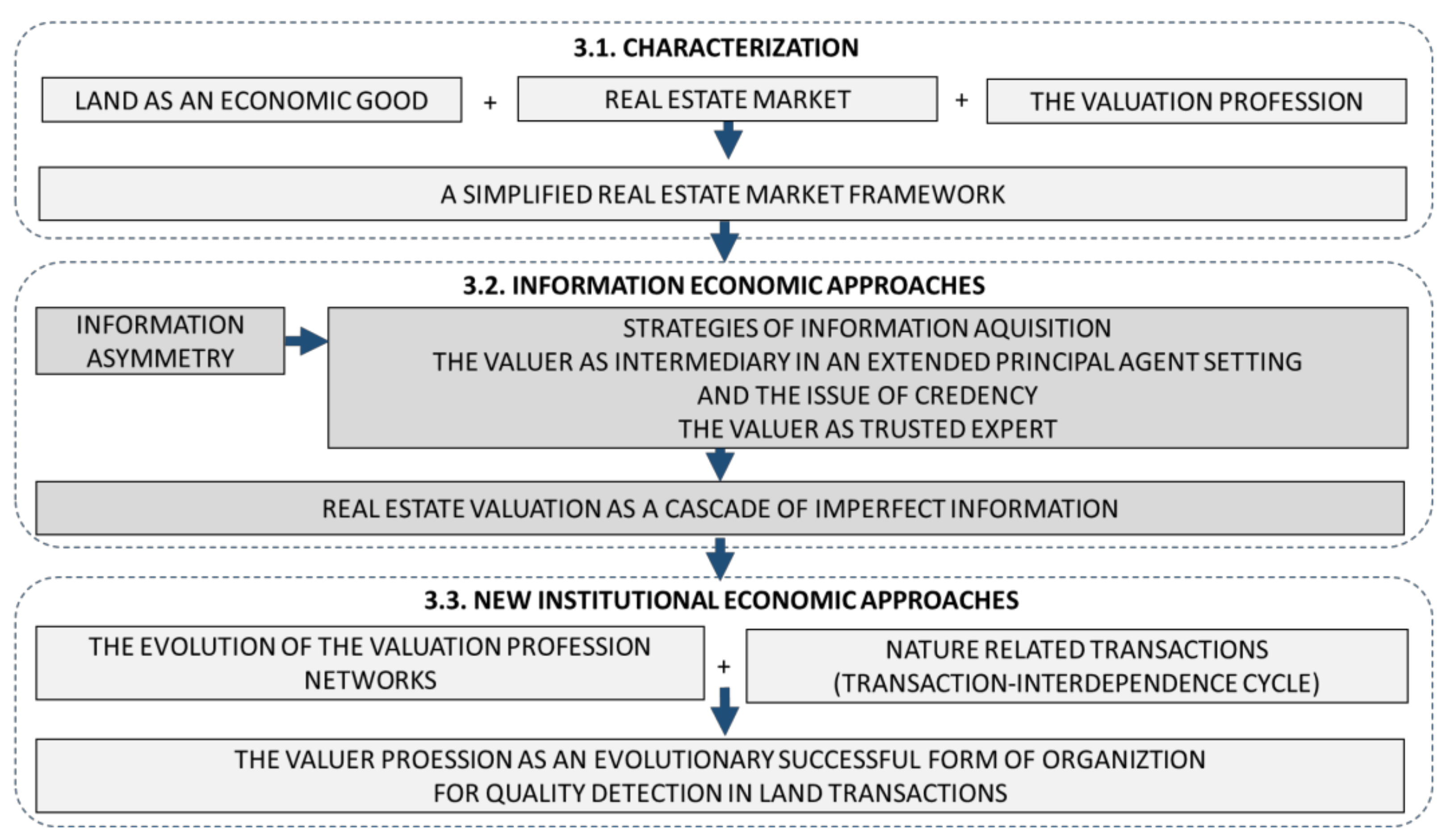

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Real Estate Good, Market and Valuation Profession

3.1.1. Real Estate as an Economic Good

3.1.2. Real Estate Market

3.1.3. The Valuation Profession

3.1.4. A Simplified Real Estate Market Framework

3.2. Information Economic Approaches

3.2.1. Information Asymmetry and the Demon of the Principle and Agent Dilemma

3.2.2. Strategies of Information Acquisition—The Buyer’s Perspective

3.2.3. The Valuer as Intermediary in an Extended Principal Agent Setting and the Issue of Credency

3.2.4. The Valuer as Trusted Expert

3.2.5. Deduced Conclusion: Real Estate Valuation as a Cascade of Imperfect Information

3.3. New Institutional Economic Approaches

3.3.1. The Evolution of the Valuation Profession Networks

3.3.2. Nature Related Transactions

3.3.3. Deduced Conclusion: The Valuer Profession as an Evolutionary Successful Form of Organization for Quality Detection in Land Transactions

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Źróbek, S.; Adamiczka, J.; Grover, R. Valuation for loan security purposes in the context of a property market crisis—The case of the United Kingdom and Poland. Real Estate Manag. Valuat. 2013, 21, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- IVSC. International Valuation Standards Council Annual Report 2019–20; IVSC: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Arruñada, B. Market and institutional determinants in the regulation of conveyancers. Eur. J. Law Econ. 2007, 23, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Closer, B.M. The Evolution of Appraiser Ethics and Standards. Appraisal J. 2007, 75, 116–129. Available online: https://www.thefreelibrary.com/The+evolution+of+appraiser+ethics+and+standards.-a0163680965 (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Morgan, J.F.W. The natural history of professionalisation and its effects on valuation theory and practice in the UK and Germany. J. Prop. Valuat. Invest. 1998, 16, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, R. The urban land economics tradition: How heterodox economic theory survives in the real estate appraisal profession. In Wisconsin “Government and Business” and the History of Heterodox Economic Theory (Research in the History of Economic Thought and Methodology; Samuels, W.J., Ed.; Emerald Group Publishing Ltd.: Bingley, UK, 2004; Volume 22, pp. 347–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagourtzi, E.; Assimakopoulos, V.; Hatzichristos, T.; French, N. Real estate appraisal: A review of valuation methods. J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 2003, 21, 383–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosen, S. Markets and diversity. Am. Econ. Rev. 2002, 92, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, W.L.; Pyhrr, S.A. Real estate valuation: The effect of market and property cycles. J. Real Estate Res. 1994, 9, 455–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endres, A.; Fraser, I.L. Environmental Economics: Theory and Policy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rubinstein, A.; Wolinsky, A. Middlemen. Q. J. Econ. 1987, 102, 581–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biglaiser, G. Middlemen as experts. RAND J. Econ. 1993, 24, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz, D.; Dent, P.; Kauko, T. (Eds.) Value in a Changing Built Environment; John Wiley & Sons: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- RICS Red Book Global Standards. Available online: https://www.rics.org/de/upholding-professional-standards/sector-standards/valuation/red-book/red-book-global/ (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- Holthaus, U. Ökonomisches Modell mit Risikobetrachtung für die Projektentwicklung. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität Dortmund, Dortmund, Germany, 11 January 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hubacek, K.; van den Bergh, J.C.J.M. Changing concepts of ‘land’ in economic theory: From single to multi-disciplinary approaches. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 56, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferber, U.; Preuß, T. Circular Land Use Management in Cities and Urban Regions–A Policy Mix Utilizing Existing and Newly Conceived Instruments to Implement an Innovative Strategic and Policy Approach, Difu-Papers; DIFU: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wikipedia—Real Estate Appraisal. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Real_estate_appraisal (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Bird, F.L. The objectives of the appraiser. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 1938, 199, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, R. The Truth Shall Set us Free: Appraisers Serve a Vital Role in U.S. Economy. National Real Estate Investor. 2014. Available online: http://nreionline.com/retail/truth-shall-set-us-free-appraisers-serve-vital-role-us-economy (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- IVSC. International Valuation Standards Council IVS 104: Bases of Value; IVSC: London, UK, 2016; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- RICS. RICS Professional Standards and Guidance, Global—RICS Valuation—Global Standards: Effective from 31 January 2020; RICS: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, P.M. Will mandatory licensing and standards raise the quality of real estate appraisals? Some insights from agency theory. J. Hous. Econ. 1998, 7, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Appraisal Foundation. 2020–21 Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP); The Appraisal Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schnaidt, T.; Sebastian, S. German valuation: Review of methods and legal framework. J. Prop. Invest. Finance 2012, 30, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coase, R.H. The nature of the firm. Economica 1937, 4, 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akerlof, G.A. The market for “lemons”: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. Q. J. Econ. 1970, 84, 488–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, B.; Leffler, K.B. The role of market forces in assuring contractual performance. J. Political Econ. 1981, 89, 615–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nelson, P. Information and consumer behavior. J. Political Econ. 1970, 78, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, C.A. The nature of equilibrium in markets with adverse selection. Bell J. Econ. 1980, 11, 108–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, R. The theory of principal and agent part 1. Bull. Econ. Res. 1985, 37, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, R. The theory of principal and agent: Part 2. Bull. Econ. Res. 1985, 37, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.A. The economic theory of agency: The principal’s problem. Am. Econ. Rev. 1973, 63, 134–139. [Google Scholar]

- Sappington, D.E.M. Incentives in principal-agent relationships. J. Econ. Perspect. 1991, 5, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stigler, G.J. The economics of information. J. Political Econ. 1961, 69, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P. Advertising as information. J. Political Econ. 1974, 82, 729–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, D.W. Financial intermediation and delegated monitoring. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1984, 51, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.; Wong, Y.Y. Buyers, sellers, and middlemen: Variations on search-theoretic themes. Int. Econ. Rev. 2014, 55, 375–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Y. Middlemen and private information. J. Monet. Econ. 1998, 42, 131–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, D.C.; Quigley, J.M. Price formation and the appraisal function in real estate markets. J. Real Estate Finance Econ. 1991, 4, 127–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, M.R.; Karni, E. Free competition and the optimal amount of fraud. J. Law Econ. 1973, 16, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balafoutas, L.; Beck, A.; Kerschbamer, R.; Sutter, M. What drives taxi drivers? A field experiment on fraud in a market for credence goods. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2013, 80, 876–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonroy, O.; Lemarié, S.; Tropéano, J.-P. Credence goods, experts and risk aversion. Econ. Lett. 2013, 120, 464–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dulleck, U.; Kerschbamer, R.; Sutter, M. The economics of credence goods: An experiment on the role of liability, verifiability, reputation, and competition. Am. Econ. Rev. 2011, 101, 526–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Waibel, C.G. Three Essays on Credence Goods: The Impact of Expert and Market Characteristics on the Level of Expert Fraud. Ph.D. Thesis, Universität zu Köln, Cologne, Germany, 22 January 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Emons, W. Credence goods monopolists. Int. J. Ind. Organ. 2001, 19, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dulleck, U.; Kerschbamer, R. On doctors, mechanics, and computer specialists: The economics of credence goods. J. Econ. Lit. 2006, 44, 5–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lerner, A.P. The concept of monopoly and the measurement of monopoly power. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1934, 1, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vatn, A. Institutions and the Environment; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Eggertsson, Þ. Economic Behavior and Institutions: Principles of Neoinstitutional Economics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe, A.J. Toward an evolutionary theory of trade associations: The case of real estate appraisers. Real Estate Econ. 1988, 16, 230–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedorn, K. Particular requirements for institutional analysis in nature-related sectors. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2008, 35, 357–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Endres, A.; Schwarze, R. Ökonomische Aspekte technischer Normen. In Umweltschutz Durch Gesellschaftliche Selbststeuerung—Gesellschaftliche Umweltnormierungen und Umweltgenossenschaften; Endres, A., Marburger, P., Eds.; Economica-Verlag: Bonn, Germany, 1993; pp. 79–115. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O.E. The new institutional economics: Taking stock, looking ahead. J. Econ. Lit. 2000, 38, 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bromley, D.W. The social construction of land. In Institutioneller Wandel und Politische Ökonomie von Landwirtschaft und Agrarpolitik; Hagedorn, K., Ed.; Campus-Verlag: Frankfurt, Germany, 1996; pp. 21–45. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, O.E. The Economic Institutions of Capitalism; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA; Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, A.A. Conflict and Cooperation: Institutional and Behavioral Economics; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. A diagnostic approach for going beyond panaceas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 15181–15187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks—The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Capstone Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bonini, S.; Emerson, J. Maximizing Blended Value—Building beyond the Blended Value Map to Sustainable Investing, Philanthropy and Organizations. Available online: https://community-wealth.org/sites/clone.community-wealth.org/files/downloads/report-bonini3.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- Sayce, S.; Sundberg, A.; Clements, B. Is Sustainability Reflected in Commercial Property Prices: An Analysis of the Evidence Base; Kingston University: Kingston, Jamaica; London, UK, 2010; Available online: https://eprints.kingston.ac.uk/id/eprint/15747/1/Sayce-S-15747.pdf (accessed on 8 June 2021).

- Dent, P.; Dalton, G. Climate change and professional surveying programmes of study. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2010, 11, 274–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.B. The turn in economics: Neoclassical dominance to mainstream pluralism? J. Inst. Econ. 2006, 2, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| First Order Keywords | Second Order Keyword |

|---|---|

| One or more included in each search. | One or more included in addition to first order keyword in searches. |

| apprais*; middlem*; survey*; valu* | assess*; asset; contract; credenc*; expert*; evolution; imperfect*; information; institution*; intermedia*; land; market; price; principal agent; profession*; property; quality; real estate; regula*; rules; standard*; uncertain* |

| Market without Valuers as Intermediaries | Market with Valuers as Intermediaries |

|---|---|

| Imperfect information causes adverse selection and the ‘lemons’ problem | Mitigation of the ‘lemons’ problem by improving information on the quality of the land |

| Agency problem between buyer and seller | Agency cascade between buyer and seller and between valuer and client |

| Parties have different strategic options to overcome agency problem | Principal agent problem regarding the estimation of product quality, in particular market risks, between seller and buyer is solved by intermediation of the valuer |

| High information seeking and processing costs | Advantage due to economies of scale, education and experience which reduce costs of screening the product quality of land |

| Parties act in their own interest | Parties act in their own interest but put ‘trust’ in the expert valuer, who must be punishable |

| Long matchmaking time between buyers and sellers | Matchmaking time shortened due to intermediary |

| Low market size or even collapse | Increased market size |

| Phases of the Transaction-Interdependence Cycle 1 | Real Estate Transaction Example with Valuer |

|---|---|

| Actors choose an action that entails transactions involving one or more actors | A site owner wants to sell a derelict piece of land to residential re-users. Potential buyers reduce willingness to pay due to uncertainties regarding uncertain former use of the site (soil pollution might be a problem). A valuer is to assess the price. |

| Such choices lead to a transfer of resource units or they affect ecosystem components by resource users | Transfer: Current (in-/formal) users have to find another plot of land/new residents transfer taxes to local municipality (away from older one) | Impact: Soil sealing as foundations for new buildings (negative)/remediation of site (positive) |

| They may also impact on the wider context of the physical or natural system | Ecological succession process stops. Remediation improves land value—ecological and economic. New use will entail increased traffic to site and related emissions and noise. |

| Ecosystems or hydrological systems respond to the changes by adaptation processes | Change of micro climate; infrastructure connections impact subsoil and groundwater level; storm water treatment could be altered |

| The outcomes affect other actors: a physical transaction occurs | Neighbouring stakeholders experience change of view, will be impacted by increased traffic; community benefits from increased tax revenue and perhaps reduced crime related to the brownfield |

| The relationship between the actors participating in the transaction changes as they recognise their interdependence regarding the use of the natural system and respond to it | Stakeholders realise conflicts, e.g., due to increased traffic or dread of release of contaminants or due to (potentially) remaining pollution level after ‘remediation’—or options, such as new jobs or safer community. Stakeholders have different views on which impacts the real estate owner is to bear and which the society, which should be reflected accordingly in the market value |

| This stimulates interaction between actors directly and indirectly such as discussion, negotiation, consensus-building on rule-making | Discussion on suitable remediation technology and acceptable pollution level. Planning of traffic and transport. Discussion on fair market value of site and diminutions to value. Discussion in valuation profession on which impacts to include in market valuation: Considering consultation of environmental experts. |

| Adaptation processes in the social system result in institutional change and new governance structures | Rule established that a trusted expert is to estimate extent of the impacts and asserts the market value. Regulations in the society determine fiduciary role of the valuer and implement enforcement/sanctioning mechanisms to prevent malpractice (such as abuse of superior credence role). The professional associations mature in their efficacy to handle complex valuation questions. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bartke, S.; Schwarze, R. The Economic Role and Emergence of Professional Valuers in Real Estate Markets. Land 2021, 10, 683. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10070683

Bartke S, Schwarze R. The Economic Role and Emergence of Professional Valuers in Real Estate Markets. Land. 2021; 10(7):683. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10070683

Chicago/Turabian StyleBartke, Stephan, and Reimund Schwarze. 2021. "The Economic Role and Emergence of Professional Valuers in Real Estate Markets" Land 10, no. 7: 683. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10070683

APA StyleBartke, S., & Schwarze, R. (2021). The Economic Role and Emergence of Professional Valuers in Real Estate Markets. Land, 10(7), 683. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10070683