Marketplace Trade in Large Cities in Poland

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

- permanent marketplaces, i.e., “a separate area or structure (square, street, market hall) with fixed retail outlets, open daily or on fixed days, open throughout the calendar year, possibly with interruptions due to reasons such as renovation, temporary lack of staff (due to holidays or illness), or periodic stock-taking”.

- seasonal marketplaces, i.e., “a separate area or structure (square, street, market hall) where retail outlets are set up for a period of up to six months in connection with increased customer traffic (e.g., coastal holiday traffic) and where these activities are repeated in the subsequent seasons”.

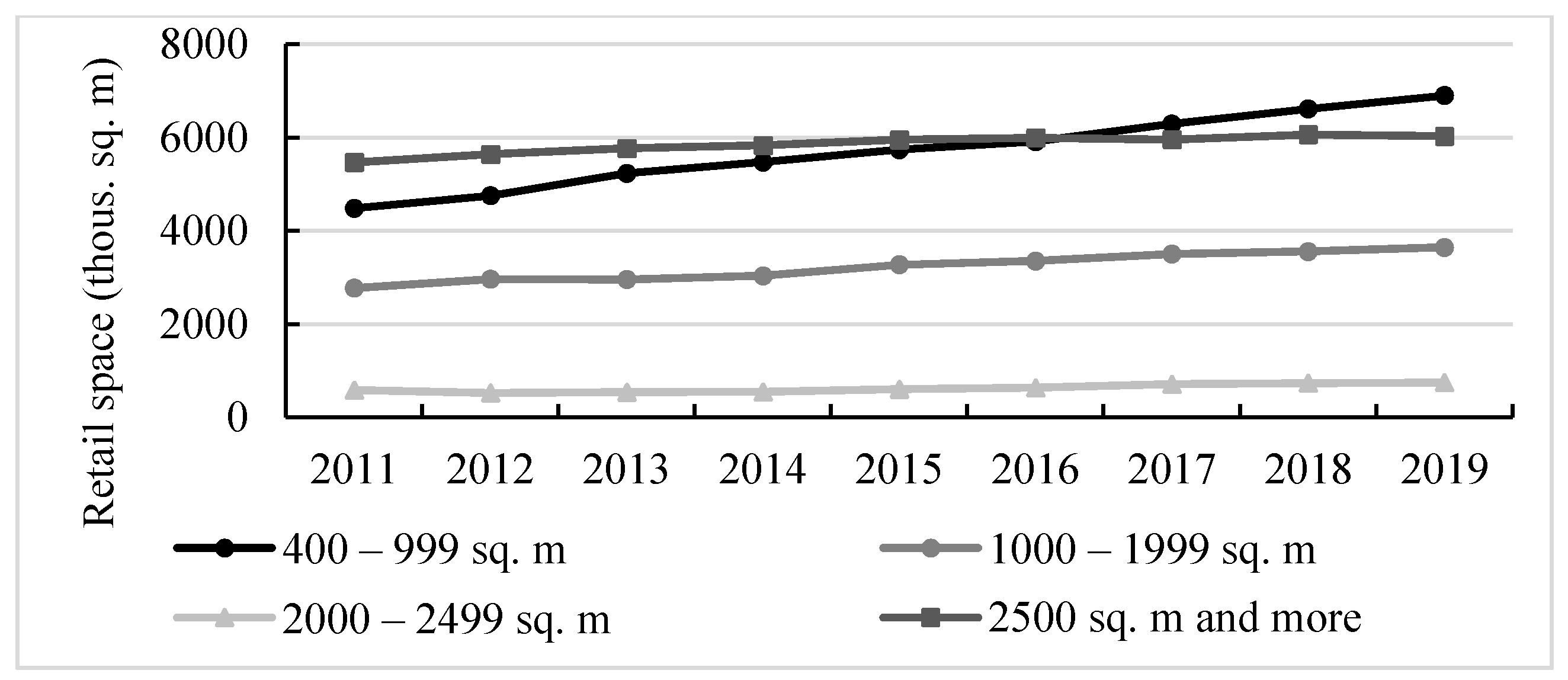

- supermarket—a shop with a sales area from 400 m2 to 2499 m2, which sells mainly using the self-service system and offers a wide range of food and non-food products of frequent purchase.

- hypermarket—a shop with a sales area of at least 2500 m2, which sells mainly in the self-service system and offers a wide range of food and non-food products for frequent purchase, usually with a car park.

- department store—a multi-department (at least two branch divisions) shop with a sales area from 600 m2 to 1999 m2 selling goods of a similar assortment to a shopping centre.

- shopping centre—a multi-department shop with a sales area of at least 2000 m2, which sells a wide and versatile range of non-food and often food products: it may also have ancillary catering and service activities.

- The starting point is the observation matrix :

- —value of the j-th variable in the i-th object,

- m—number of objects,

- n—number of variables.Variables describing the objects belong to one of three types: stimulants, for which the highest possible value is desirable; destimulants, for which the lowest possible value is desirable; and nominants, for which a specific value is desirable. Before proceeding any further, all nominant variables must be transformed into stimulants. As our dataset does not contain any nominants, this step is skipped.

- 2.

- The values of each variable should be normalised in order to strip them of units and present each on the same scale. The original application of the composite measure of development involved the use of the standard score. Therefore, we use this method:

- —mean value of the j-th variable,

- —standard deviation of the j-th variable,

- —normalised value of the j-th variable in the i-th object.

- 3.

- We calculate the Euclidean distances of each object from the pattern:

- 4.

- We determine the value of the composite variable for each object:

- 5.

- We rank the objects in descending order of the value of the composite variable.In our research, we assume that all variables have equal weight.

4. Results

- —the number of permanent marketplaces,

- —the number of seasonal marketplaces,

- —total marketplace area (m2),

- —annual revenue from all marketplaces (in thous. PLN),

- —the number of large shops (hyper- and supermarkets, department stores, and shopping centres).

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carter, F.W. Trade and Urban Development in Poland: An Economic Geography of Cracow, from Its Origins to 1795 (Vol. 20); Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabi, D. The Market and the City: Square, Street and Architecture in Early Modern Europe; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Koter, M.; Kulesza, M. The study of urban form in Poland. Urban Morphol. 2010, 14, 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Czakó, Á.; Sik, E. Characteristics and Origins of the Comecon Open-air Market in Hungary. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 1999, 23, 715–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sik, E.; Wallace, C. The Development of Open-air Markets in East-Central Europe. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 1999, 23, 697–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karasiewicz, G.; Nowak, J. Looking back at the 20 years of retailing change in Poland. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2010, 20, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kropiwnicki, J. Fenomen bazarów. Acta Univ. Lodz. Folia Oecon. 2003, 170, 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Zuzańska-Żyśko, E.; Sitek, S. Rola handlu targowiskowego w rozwoju miast. In Człowiek w Przestrzeni Zurbanizowanej; Soja, M., Zborowski, A., Eds.; Instytut Geografii i Gospodarki Przestrzennej UJ: Kraków, Poland, 2011; pp. 271–281. [Google Scholar]

- Heffner, K.; Twardzik, M. The impact of shopping centers in rural areas and small towns in the outer metropolitan zone (the example of the Silesian Voivodeship). Eur. Countrys. 2015, 7, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Twardzik, M.; Heffner, K. Small Towns and Rural Areas–as A Prospective Place of Modern Retail Trade Formats in Poland. Eur. Countrys. 2019, 11, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gavurova, B.; Belas, J.; Bilan, Y.; Horak, J. Study of legislative and administrative obstacles to SMEs business in the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Oeconomia Copernic. 2020, 11, 689–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaźmierska-Zatoń, M.; Zatoń, W. The Role of Barriers to the Activity of Industrial Enterprises in the Evaluation of the Business Tendency in Poland. Folia Oeconomica Stetin. 2020, 20, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, F.-W. Rediscovering Herb Lane: Application of Design Thinking to Enhance Visitor Experience in a Traditional Market. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledesma, E. How Urban Planning Impacts Latino Vendor Markets. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fresno, J.M.; Koops, R. Market Trading in Europe: Methodological Guide for the Analysis and Enhancement of Markets in Public Areas; Universidad Autonoma de Madrid: Madrid, Spain, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, S.; Waley, P. Traditional Retail Markets: The New Gentrification Frontier? Antipode 2013, 45, 965–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Janssens, F.; Sezer, C. Marketplaces as an Urban Development Strategy. Built Environ. 2013, 39, 169–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünlü-Yücesoy, E. Constructing the Marketplace: A Socio-Spatial Analysis of Past Marketplaces of Istanbul. Built Environ. 2013, 39, 190–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, N.; Mackay, M.; Martín Perez, O.; Navarro, G.; Partridge, A.; Portinaro, A.; Scheffler, N. Urban Markets: Heart, Soul and Motor of Cities; City of Barcelona Institut Municipal de Mercats de Barcelona (IMMB): Barcelona, Spain, 2015; Available online: https://urbact.eu/sites/default/files/urbact_markets_handbook_250315.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2021).

- Janssens, F. Street food markets in Amsterdam: Unravelling the original sin of the market trader. In Street Food: Culture, Economy, Health and Governance; Cardoso, R.C.V., Companion, M., Marras, S.R., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 98–116. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, S. City Publics: The (Dis)enchantments of Urban Encounters; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, S. The Magic of the Marketplace: Sociality in a Neglected Public Space. Urban Stud. 2009, 46, 1577–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- URBACT Markets. Available online: http://urbact.eu/urbact-markets (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- Janssens, F.; Sezer, C.; Freek, J.; Ceren, S. ‘Flying Markets’ Activating Public Spaces in Amsterdam. Built Environ. 2013, 39, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Torre, P.L.; Coque, J. From Food Waste to Donations: The Case of Marketplaces in Northern Spain. Sustainability 2016, 8, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Polyák, L. Exchange in the street: Rethinking open-air markets in Budapest. In Public Space and the Challenges of Urban Trans-formation in Europe; Madanipour, A., Knierbein, S., Degros, A., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 48–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, J. Insurgent Public Space: Guerrilla Urbanism and the Remaking of Contemporary Cities; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mehta, R.; Gohil, C.; Rushank, M.; Chintan, G. Design for Natural Markets: Accommodating the Informal. Built Environ. 2013, 39, 277–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.K.; Ban, Y.U. Spatial Configurations for The Revitalization of a Traditional Market: The Case of Yukgeori Market in Cheongju, South Korea. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morales, A. Public Markets as Community Development Tools. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2009, 28, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, C.L.; Sterling, S. From fake market to a strong brand? The silk street market in Beijing. Built Environ. 2013, 39, 224–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, R.; Baxter, I.; Collinson, E.; Gannon, M.J.; Lochrie, S.; Taheri, B.; Thompson, J.; Yalinay, O. The traditional marketplace: Serious leisure and recommending authentic travel. Serv. Ind. J. 2018, 38, 1116–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sirirak, W.; Pitakaso, R. Marketplace Location Decision Making and Tourism Route Planning. Adm. Sci. 2018, 8, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reijndorp, A. The city as bazaar. In Open City: Designing Coexistence; Rieniets, T., Sigler, J., Christiaanse, K., Eds.; SUN: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 93–101. [Google Scholar]

- Hiebert, D.; Rath, J.; Vertovec, S. Urban markets and diversity: Towards a research agenda. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2013, 38, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schappo, P.; Van Melik, R. Meeting on the marketplace: On the integrative potential of The Hague Market. J. Urban. 2016, 10, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bareja-Wawryszuk, O.; Gołębiewski, J. Economic functions of open-air trade in the context of local food system development. Roczniki 2014, 16, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Płaziak, M.; Szymańska, A.I. Operation of Small Businesses in Open-Air Markets in Poland Based on the Example of Kraków. Przedsiębiorczość-Edukacja 2017, 13, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Płaziak, M.; Szymańska, A. The attractiveness of open-air markets for shopping in a large CEE city: The example of Kraków, Poland. Polish Sociol. Rev. 2019, 4, 493–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Velde, M.; Marcińczak, S. From iron curtain to paper wall: The influence of border regimes on local and regional economies–The life, death, and resurrection of bazaars in the Łódź region. In Borderlands: Comparing Border Security in North America and Europe; Brunet-Jailly, E., Ed.; University of Ottawa Press: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2007; pp. 165–196. [Google Scholar]

- Świetlik, K. Marketplace trade in Poland. State in 2008–2018 and prospects. Probl. Agric. Econ. 2020, 3, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klima, E.; Zajączkowski, J. Marketplace retail in Poland in the years 1995–2006. Space Soc. Econ. 2008, 8, 143–154. [Google Scholar]

- Chmielinski, P.; Hamulczuk, M. Importance and territorial diversification of marketplace trade in Poland. J. Environ. Stud. 2018, 1, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bąk, A. Comparative analysis of selected linear ordering methods based on empirical and simulation data. Res. Pap. Wrocław Univ. Econ. 2018, 508, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targiel, K. Metoda sumy ważonej. In Wielokryterialne Wspomagania Decyzji. Metody i Zastosowania; Trzaskalik, T., Ed.; Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne: Warszawa, Poland, 2014; pp. 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Hellwig, Z. Zastosowanie metody taksonomicznej do typologicznego podziału krajów ze względu na poziom rozwoju oraz zasoby i strukturę wykwalifikowanych kadr. Przegląd Stat. 1968, 15, 307–326. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, C.-L.; Yoon, K. Multiple Attribute Decision Making—Methods and Application a State-of-the-Art Survey; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1981; Volume 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellwig, Z. On the optimal choice of predictors. In Towards a System of Human Resources Indicators for Less Developed Countries: Papers Prepared for a UNESCO Research Project; Gostowski, Z., Ed.; Ossolineum—The Polish Academy of Sciences: Wrocław, Poland, 1972; pp. 69–90. [Google Scholar]

- Hellwig, Z. Procedure of evaluating high-level manpower data and typology of countries by means of the taxonomic method. In Towards a System of Human Resources Indicators for Less Developed Countries: Papers Prepared for a UNESCO Research Project; Gostowski, Z., Ed.; Ossolineum—The Polish Academy of Sciences: Wrocław, Poland, 1972; pp. 115–134. [Google Scholar]

- Nermend, K. Properties of Normalization Methods Used in the Construction of Aggregate Measures. Folia Oeconomica Stetin. 2012, 12, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balcerzak, A.P. Multiple-criteria Evaluation of Quality of Human Capital in the European Union Countries. Econ. Sociol. 2016, 9, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miłek, D. Spatial differentiation in the social and economic development level in Poland. Equilib. Q. J. Econ. Econ. Policy 2018, 13, 487–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, P. Regional variety in quality of life in Poland. Oeconomia Copernic. 2018, 9, 381–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pełka, M. Assessment of the Development of the European Oecd Countries with the Application of Linear Ordering and Ensemble Clustering of Symbolic Data. Folia Oeconomica Stetin. 2019, 19, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Korzeb, Z.; Niedziółka, P. Resistance of commercial banks to the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of Poland. Equilib. Q. J. Econ. Econ. Policy 2020, 15, 205–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszko-Wójtowicz, E.; Grzelak, M.M. Macroeconomic stability and the level of competitiveness in EU member states: A comparative dynamic approach. Oeconomia Copernic. 2020, 11, 657–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszkowska, E.; Filipowicz-Chomko, M. Measuring Sustainable Development Using an Extended Hellwig Method: A Case Study of Education. Soc. Indic. Res. 2021, 153, 299–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmytrów, K. Comparison of Several Linear Ordering Methods for Selection of Locations in Order-picking by Means of the Simulation Methods. Acta Univ. Lodz. Folia Oeconomica 2018, 5, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walesiak, M. Visualization of linear ordering results for metric data with the application of multidimensional scaling. Ekonometria. Econom. 2016, 2, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markets in Wrocław You Must Visit (Before Some Disappear). Available online: https://blog.inyourpocket.com/poland/2017/01/markets-wroclaw/ (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Kraków Markets. Available online: https://www.inyourpocket.com/krakow/shopping/markets (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- The Best Markets in Warsaw, Poland. Available online: https://theculturetrip.com/europe/poland/articles/the-best-markets-in-warsaw/ (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Flea & Street Markets in Central Poland. Available online: https://www.tripadvisor.com/Attractions-g274820-Activities-c26-t142-Central_Poland.html (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Christmas Markets in Poland. Available online: https://theculinarytravelguide.com/christmas-markets-in-poland/ (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Morales, A. Peddling policy: Street vending in historical and contemporary contest. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 2000, 20, 76–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, A. Planning and the Self-Organization of Marketplaces. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2010, 30, 182–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metaxas, T.; Juarez, L.; Gaby, G. Planning and Marketing the City for Sustainability: The Madrid Nuevo Norte Project. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deffner, A.; Karachalis, N.; Psatha, E.; Metaxas, T.; Sirakoulis, K. City marketing and planning in two Greek cities: Plurality or constraints? Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 28, 1333–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsas, C.J.L. City centre regeneration in the context of the 2001 European capital of Culture in Porto, Portugal. Local Econ. 2004, 19, 396–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cities | Years | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | |

| Warszawa | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 |

| Białystok | 13 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Bydgoszcz | 12 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| Częstochowa | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Gdańsk | 16 | 16 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 | 14 |

| Gdynia | 14 | 2 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Katowice | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Kraków | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Lublin | 11 | 12 | 8 | 7 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 9 |

| Łódź | 7 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 6 |

| Poznań | 5 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 15 |

| Radom | 10 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Sosnowiec | 15 | 15 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 |

| Szczecin | 8 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 7 | 8 |

| Toruń | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 13 |

| Wrocław | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bieszk-Stolorz, B.; Dmytrów, K. Marketplace Trade in Large Cities in Poland. Land 2021, 10, 933. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10090933

Bieszk-Stolorz B, Dmytrów K. Marketplace Trade in Large Cities in Poland. Land. 2021; 10(9):933. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10090933

Chicago/Turabian StyleBieszk-Stolorz, Beata, and Krzysztof Dmytrów. 2021. "Marketplace Trade in Large Cities in Poland" Land 10, no. 9: 933. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10090933

APA StyleBieszk-Stolorz, B., & Dmytrów, K. (2021). Marketplace Trade in Large Cities in Poland. Land, 10(9), 933. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10090933