1. Introduction

Historical centers nowadays often face problems related to the loss of multifunctionality, a situation that can lead to the alteration of their characteristics and sometimes the loss of their historical value and authenticity. The overdevelopment of tourism and leisure activities can also create serious problems in the functionality of the city, and it can result in the loss of their inhabitants. Maintaining a balance between different land uses, from commercial and touristic to residential purposes, is a precondition for the sustainable development of historic cities [

1,

2]. This has been pointed out in texts dealing with the principles of urban conservation [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7] and analyzed in the principles of sustainable development [

1,

2,

8,

9]. According to the Valetta Principles:

“The loss and/or substitution of traditional uses and functions, such as the specific way of life of a local community, can have major negative impacts on historic towns and urban areas. If the nature of these changes is not recognized, it can lead to the displacement of communities and the disappearance of cultural practices, and subsequent loss of identity and character for these abandoned places. It can result in the transformation of historic towns and urban areas into areas with a single function devoted to tourism and leisure and not suitable for day-to-day living. Retention of the traditional cultural and economic diversity of each place is essential, especially when it is characteristic of the place. Historic towns and urban areas run the risk of becoming a consumer product for mass tourism, which may result in the loss of their authenticity and heritage values”.

Furthermore, in historical cities with commercial and touristic value, historical buildings are sometimes abandoned because of the difficulties in adaptive reuse [

2]. In other situations, the new uses relevant to tourism and leisure activities eventually can lead to the buildings’ degradation. Tourism can prove to be economically beneficial to historic centers, but an over-emphasis on supporting tourist activity may damage the cultural assets themselves [

10] and cause depreciation in the long run.

Many theoretical texts of urban preservation experts deal with the issue of the monoculture of tourism activities [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15], and the problem is thoroughly studied in countries of the European South. For example, Venice in Italy [

10] (pp. 162–186), or the walled city of Mdina in Malta [

16] (pp. 75–94), have been turned into touristic parks or “museum-cities” and their few remaining inhabitants bare the cost of overtourism. In another case, the city of Antalaya, on Turkey’s south coast, was in the process of being developed through tourism, but the dominance of the commercial profit resulted in turning the city into another “overdeveloped historic town, devoid of character” [

16] (pp. 99–123). In the north, there are some successful examples of urban conservation strategies, such as the city of York in England [

16] (pp. 38–68) or the city of Bruges in Belgium [

10] (pp. 8–30), but both of them still face the disappearance of other economic activities than tourism and of course the problems of touristic pressure over their inhabitants.

Ιn Greece, several urban studies that attempt to regulate the issue of land use have been published [

17,

18,

19,

20], but their effectiveness is questionable. One of the main reasons for this is the fact that past urban planning studies rarely consider the need for preservation of the cultural heritage of the place, despite the fact that this is an essential part of urban planning. Examples of historical city centers in Greece that have been developed for touristic purposes and face these challenges are those of Athens [

20], Rhodes [

21], Corfu [

22], Nafplio, etc. These urban plans propose the revitalization of the historical city in a sustainable way, focusing on the involvement of the local society, and the harmonic coexistence of the different uses [

21]. In general, since 1975, the protection of separate monuments or settlements in Greece is under the authorization of the State, while the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Environment are choosing the settlements or buildings that should be under protection [

23]. The Historical Commercial Triangle of Athens, which is the case study of this article, is part of the Historical City of Athens, so, on the one hand, it is protected as a traditional settlement, while, on the other hand, most of the historical buildings are also individually protected.

Τhis article, based mainly on the results of extensive field research, explores the historical and functional physiognomy of the Historical Commercial Triangle in Athens, as an important part of its historical center. The results and discussion presented try to emphasize the importance of maintaining the multifunctionality and the balance of the land use development as the only way to achieve sustainability and preserve the historical character of the city center. It also attempts to highlight the consequences of the more intense than ideal presence of leisure and touristic uses in the area, arguing that these dominating uses are suppressing the traditional commercial ones and are simultaneously displacing the inhabitants. Ultimately, this paper concludes by proposing possible solutions for the problem presented above, focusing on the area’s multifunctional character and the protection of its historical elements.

The context is divided into five sections.

Section 1 is the present, introducing the context of the article, the main issue in question and the structure of the paper.

Section 2 indicates the data sources, the methodology and introduces the analysis of the area of focus. The results of the field work are reported in

Section 3, through a detailed presentation of maps and diagrams. The particular urban, historical, functional and architectural characteristics of the Historical Commercial Triangle, which comprise a rich collage of elements coming from different eras, styles and morphologies, are highlighted. In

Section 4, the issues that the area faces are outlined, focusing on the problems concerning the land uses and the poorly maintained or abandoned buildings, galleries and open spaces. Finally, the problems are summarized in

Section 5, concluding on the challenges that were identified in relation to the area and the suggestions in order to address these issues. The presented proposals are based on the necessity of choosing the appropriate land uses and the idea of reusing abandoned buildings through employing certain preservation strategies.

2. Materials and Methods

The project presented in this article is based on an assignment produced for the purposes of the course “Protection and Preservation of a historical urban center or settlement”, under the supervision of E. Maistrou, E. Konstantinidou, M. Balodimou and T. Mikrou. The course was released as part of the authors post-graduate studies in the “Protection of Monuments” MSc, in the School of Architecture, NTUA.

The methodology framework of this article is shown in

Figure 1. The data used for both the assignment and the subsequent article, concerning the public space, the circulation, the architecture and the socio-economic characteristics of the area, were collected via extensive field research, from September 2020 until January 2021. There was an effort to document the state of the historical urban area, as a crucial part of the methodology used, in the way UNESCO’s Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape theoretical text presents it:

“it is essential to document the state of urban areas and their evolution, to facilitate the evaluation of proposals for change, and to improve protective and managerial skills and procedures”.

Subsequently, the current situation data were collected on site, using photography and handmade maps concerning the land uses, the circulation, the public space, and the buildings (empty buildings, historical buildings, height, date of construction). In this step of the research, the background map of the area (in CAD) was provided by the Greek Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport’s open architectural contest of ideas entitled: “Renovation of the center of Athens”, held in February 2019 [

24]. Especially for the historical buildings of the Historical Commercial Triangle, the team produced a thorough piece of research including historical and architectural elements, the morphology, the current uses of the building, the alterations, the maintenance status and the type of protection (for the case of the listed monuments). Especially for the listed buildings, the archive of the traditional settlements and listed buildings of the Ministry of Environment [

23] and the archive of the Archaeology of the City of Athens [

25] were the most important information resources.

In addition, an extended bibliographic research was conducted, focusing on the history, the urban development of the area and the Greek legal framework. The history of the Historical City Center of Athens is long, starts before the Ancient Times and is extensively analyzed in Traulos J., Urban development of Athens, 2005, dated back to the Ancient Times (600 BC) until 1950 [

26], as well as K. Mpiris, Athens, 2005 [

27], while the modern history of urban development and architecture in Athens can be found in the books of Karidis, D, 2008 [

28], Vatopoulos, Ν., 2008 [

29] and Sarigiannis, G., 2000 [

30]. The thorought research of J. Travlos concerning the urban development of the city of Athens is the main historical source for this article [

26].

The referenced older and more recent urban design studies concerning the Historical Commercial Triangle were used in order to compare and verify the current data. The main urban research used to compare the field data with previous periods was the Research Program executed in 1989–1991 in the National Technical University of Athens, conducted by Professor Aravantinos A. for the Municipality of Athens. This research is an extensive analysis of the Commercial Triangle of Athens in 1990, including field data and mapping, as well as theoretical and legal background [

17]. This research is also a source of information concerning the history and the legal framework of the Commercial Triangle of that era. It emphasized in the socio-economic characteristics of every quarter in the whole area of the Commercial Triangle, presented in analytical tables and diagrams. This socio-economic information (i.e., land use, type of commerce for the commercial uses, number of employees in every company, etc.) concluded in a series of maps of analysis that led to the proposals. Other important bibliographical sources concerning the urban structure and development of the Historical Commercial Triangle of Athens were provided by: the Ministry of Infrastructure and Transport, 2019 [

24], Gkountra A, 2007–2008 [

31], Serraos K., Christoforaki K., et al. 2016–2017 [

32].

The current paper follows a different methodology, as it focuses from the beginning of the field research on the historical character of the area, which was identified to be the traditional commercial market and the architecture. The maps of the current situation, the problems and the final proposals were formed around the matter of cultural heritage, and were then expanded in a more general socio-economic and urban framework. The recent research used as a reference was the “2019 data issue” of the open architectural contest of ideas entitled: “Renovation of the center of Athens” [

24]. The bibliographical research was also enriched by international and national sources and case studies [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

The legal framework of the Commercial Triangle starts in the 19th century with some fragmentary urban structure regulations (i.e., the construction of Aiolou St. and Athinas St.) [

17]. Until the decade of 1970, only a few urban renovations took place (road widening, construction of galleries). In this decade, the oldest neighborhoods of the city center (including the Commercial Triangle) were characterized as “Historical City Center of Athens” (Government Gazette (21-9/13-10-1979, FEK 567D) [

33]). The historical character of the Historical Commercial Triangle has been protected since 1985 (Government Gazette (FEK 349D/1985) [

34]), when an extended legal framework was conducted, including a long list of 260 historical buildings as well as restrictions in land uses (Article 6: the disturbing uses, such as industrial uses, are forbidden, and the compatibility of every new use should be verified. As for the land uses, there is a plethora of uses allowed, including: residency, administrative uses, commercial uses, religion, touristic and leisure activities, offices, and cultural and educational uses (Government Gazette (FEK 704D/1997, FEK 1851B/2004) [

18]).

Our study area is part of a larger area (39.7 ha [

24]), namely, the Commercial Triangle. It is located in the heart of the Historical City Center of Athens and is playing a crucial role for the city center on a cultural, commercial and administrative level. The Commercial Triangle is enclosed by Mitropoleos St., Stadiou St., and Athinas St. and its neighboring areas are: Syntagma, Monastiraki, Psiri, Omonoia and Panepistimio (

Figure 2a). The focus of analysis is the oldest part of the Commercial Triangle (Historical Commercial Triangle), an area of about 18.1 ha [

24], which contains 578 buildings. The area is surrounded by Evripidou St. on the north, Praxitelous St., Lekka St. and Voulis St. on the east, Ermou St. on the south and Athinas St. on the west (

Figure 2b). The Evripidou St. constitutes an axis that separates the Historical Commercial Triangle from the “Varvakios Agora”, the largest traditional food market of Athens.

The area is characterized by many public squares, which are located both in the center of the Historical Commercial Triangle (Chrysospyliotissa sq. shown in

Figure 3a, Agias Eirinis sq.), and at the area’s periphery (Monastiraki sq., Agioi Theodoroi sq. and Korai sq.). Along with these big open spaces, the intersection of several large pedestrian streets in the area creates additional small squares, forming a complex network of open spaces, which facilitates and encourages pedestrians’ movement (

Figure 3b).

Furthermore, this particular part of the city is not only the oldest part of the Commercial Triangle, but also one of the oldest neighborhoods in Athens. The history of the area, as mentioned above, started before the Ancient Times. Until the Athens Ottoman Occupation (1456), the Historical Commercial Triangle was a suburban area that connected the city of Athens with the outer gates of Athens and the rural areas (i.e., the axis of Agiou Markou—Evaggelistrias) [

26] (pp. 46–47). From 1456 and afterwards, this area never stopped being inhabited. Most of the streets, however, were constructed during the Athens Ottoman Occupation years (1456–1830) [

26] (pp. 192–193), forming an urban fabric that even nowadays is largely characterized by narrow and irregular streets. This organic formation of the area is only interrupted by three central axes (Ermou St., Athinas St. and Aiolou St.) that were constructed after the founding of the new Greek state in 1834–1836 [

27] (p. 59) and were part of Leo Von Klenze’s “City of Athens” plan in 1834, as shown in

Figure 4. Today, these streets remain some of the most important streets in the city center. In general, in the Historical Commercial Triangle, one can trace different historical eras of the city’s evolution, imprinted in the urban fabric (

Figure 5).

4. Discussion

Summarizing the information analyzed in

Section 3, the Historical Commercial Triangle is one of the oldest neighborhoods of the city, and this is evident by its medieval urban structure with narrow irregular streets, but also by its rich architectural heritage. It also becomes evident that the architectural footprint of the area is the result of a construction process that lasted more than 150 years and that consequently nowadays includes a wide variety of architectural forms and buildings that differ both in age and size. We would argue that the traditional character of the Historical Commercial Triangle is based on the “coexistence”: the coexistence of a ground-floor shop next to a six-story office building, the coexistence of a neoclassical two-story house with a shop on the ground floor next to a modern multi-story building with a gallery in the entrance, the coexistence of a well reserved neoclassical building next to a badly maintained neoclassical building ready to be demolished (

Figure 19). The area’s value does not only concern the rich urban fabric and the buildings’ architecture, but it also concerns the area’s rich history and its special socio-economic factors that have shaped today’s image. Most of all, the traditional commercial use has given a unique character as well as a significant role in the city of Athens.

All of the above analysis revealed some serious problems. The aim of the following arguments is to address the reason why this problem happened while keeping in mind the abstract from the UNESCO’s recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape [

6] (p. 1): “… rapid and frequently uncontrolled development is transforming urban areas and their settings, which may cause fragmentation and deterioration to urban heritage with deep impacts on community values …”.

In order to better understand how the character of the neighborhood has changed over the last decades, a comparison was made between 1990 and 2020 [

17]. The data of the maps that depict the situation in 1990 come from the extended research of the NTUA Program focused on the Commercial Triangle (1989–1991) that contained a thorough field survey [

17]. The data of the current situation (2020) come from the team’s field research. In the last 30 years, there has been a large increase in leisure activities followed by a large decrease in commercial shops. The maps below (

Figure 20 and

Figure 21) show the spatial redistribution of these uses from 1990 to 2020, and the chart below (

Figure 22) shows the overall compared elements. In 1990, the west part of the Historical Commercial Center had almost exclusively commercial shops, while nowadays the number of these shops is notably reduced. On the other hand, in 1990, the neighborhood had only a few leisure spots, while 30 years later, this new activity is flourishing, mainly in Agias Eirinis square and across Aiolou St.

Overall, comparing the current number of retail shops with the number of these shops in 1990 shows a great decline in traditional commercial uses. On the contrary, the tourism and leisure activities are blooming.

Moreover, 260 of the 578 buildings in the area are empty or partly empty, while many of the historical buildings are in poor condition today, or the continuous adjustments have destroyed their architectural value. As for the galleries of the area, they are mostly abandoned, creating an overall picture of abandonment. It is a fact that one of the main problems and disadvantages of the Historical Commercial Triangle of Athens is the large number of abandoned buildings and galleries, many of which are historically preserved buildings of special architectural value. In general, most parts of the area are full of life during daytime. However, the abandonment and degradation of the neighborhood is obvious mainly due to the empty ground-floor shops and galleries.

The above observations led us to the conclusion that this problem is directly related to the monoculture of uses around tourism and leisure that dominate the area and has also contributed to the rapid decline of permanent residents [

35]. The reasons for this decline are manifold. Many residents have left the neighborhood and have transformed their homes to hotels or cafes and bars in an effort to profit from the touristic value of the area. Some others have chosen to move out of the area due to the unpleasant environment created by the intense leisure and touristic activities taking place in the Historical Commercial Triangle. Lastly, the dramatic increase in short-term renting (air-BnB) has not only led to the decline of permanent residents, but has also contributed to the area’s rent increase [

35]. This has, of course, forced many of the residents to relocate to more affordable neighborhoods.

As for the small shops and galleries, many of them are currently abandoned both due to the unregulated development of leisure areas and touristic activities, but also because of the type of commercial activity that used to flourish in these small shops (electrical shops, tailor shops, repairing shops and small handicrafts). This type of commercial activity tends, on a more general level, to disappear nowadays, due to its replacement by other more advanced and contemporary services. These shops and galleries (many of which are of great architectural value) cannot be easily adapted to this new kind of market that includes malls and big department stores, so they remain unused. It is also important to mention that the local market has shrunk all the more due to the establishment of competitive large shopping centers (malls, etc.) in city suburbs as well as in other main streets of the historic center, such as in Panepistimiou St.

All the problems mentioned above are combined with large traffic problems in the area. The public transportation approaches the area but it does not reach the center of the Historical Commercial Triangle: bus stops are located in the main axes of the area’s periphery (Athinas St., Evripidou St., Ermou St., Praxitelous-Lekka St.), a metro station is located in Monastiraki square, and taxi stops are traditionally found on Athinas St. Moreover, vehicles are allowed to enter the old Triangle only through two axes: Kolokotroni St. and Perikleous-Athinaidos-Agias Eirinis St. These traffic regulations do not meet the commercial needs of the area (product transfer, consumer transportation and parking), as well as the parking needs of the permanent residents.

This situation creates an overall image of abandonment of the public space, which already appears quite degraded due to the lack of trees and parks and the fragmentary interventions that took place in recent decades. The empty galleries in particular, the significant urban value of which is already mentioned, make this image of abandonment even more obvious. Undoubtedly, there was never any holistic intervention in the area. In fact, even the studies that refer to the urban revitalization of the Historical Commercial Triangle are very few. The latest of them was conducted 30 years ago (Aravantinos, 1990) [

17], so, naturally, some parts of the analysis are outdated.

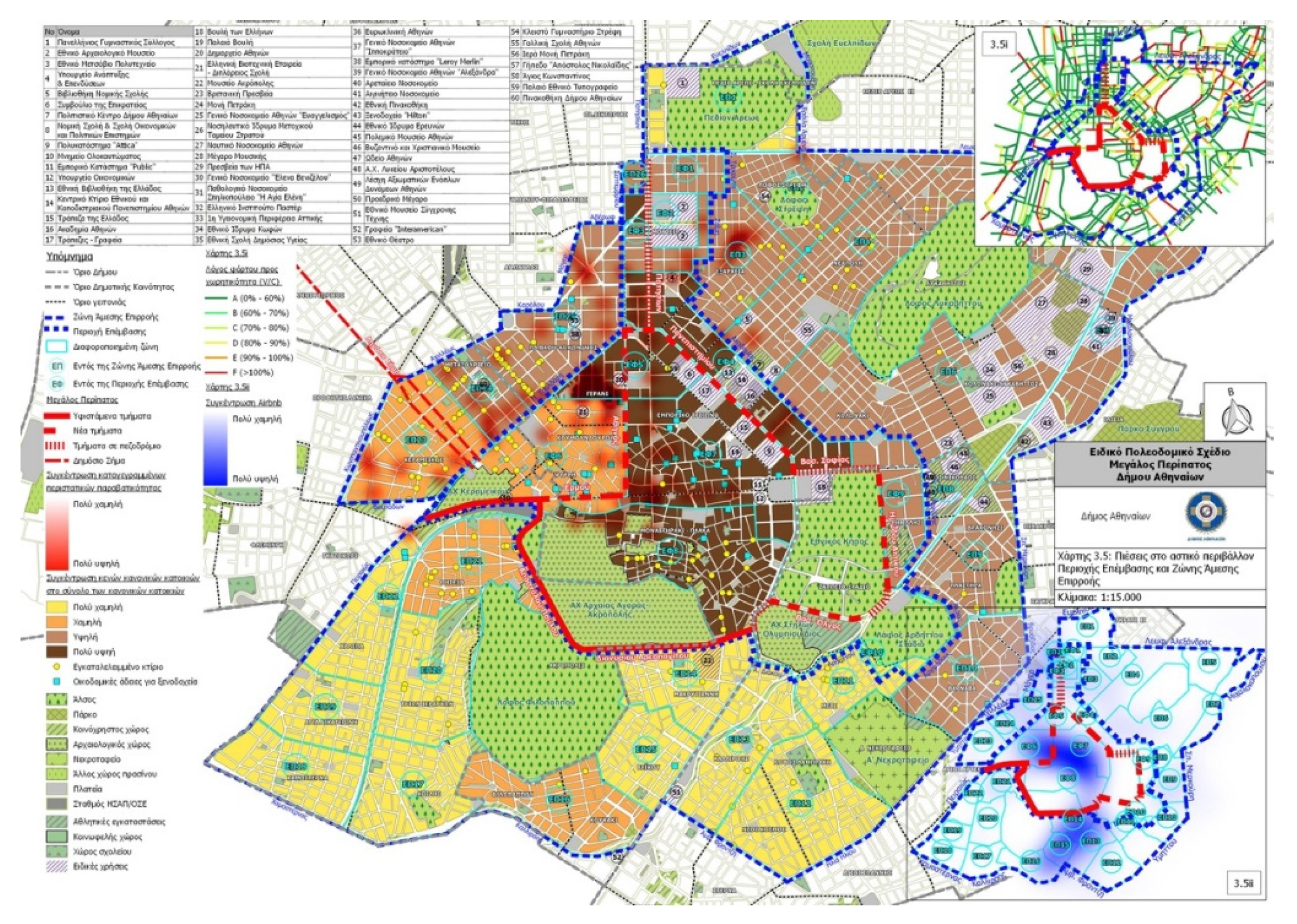

At this point, it is worth mentioning the latest urban project concerning the Athens city center (including the Historical Commercial Triangle) called “Megalos Peripatos” (The Great Walk) (

Figure 23). The Athens Master Plan—The Great Walk was established by the Municipality of Athens and its application started in the summer of 2020 [

20]. This project is mainly a circulation plan that intends to create an extended network of pedestrian streets all over the Historical City Center of Athens in order to accommodate the tourists and visitors. According to this study, all the non-pedestrian streets of the neighborhood’s center and suburbs are becoming pedestrian: Athinas St., Aiolou St., Ermou St. (from Aiolou St. to Thissio), Kolokotroni St., Praxitelous-Lekka St., and Peri-kleous-Athinaidos-Agias Eirinis St. Therefore, there will be no vehicles approaching the area, with the exception of Evripidou St. and Voulis St. In parallel, there are no plans for the provision of parking or the expansion of public transportation.

Thus, it becomes evident that this project focuses on the promotion of the city center from a touristic point of view, with no deep analysis on the different needs of its neighborhoods. This is incredibly evident in two main parts of the proposal. First, in the analysis of the study area and the published masterplan, the project has identified only one abandoned building—when of course, based on authors’ field research, this is not the case. Second, in the same masterplan, there is the provision of additional hotels in the old Historical Commercial Triangle and the neighboring areas, a provision that enhances the touristification of the area and ignores residents’ needs. However, if this path is followed, it is possible that even more small shops will be abandoned due to the irregular development of tourist activities and the future circulation difficulties, because the transportation of the employees, the visitors, the residents and the products will become even more difficult. More specifically, in the case of Athinas St., which is the area’s main artery, doubts can be raised on the actual need for its pedestrianization. Aiolou St. Is a large pedestrian street parallel and very close to Athinas St., and it seems that the need for a central pedestrian artery is already met in the area. The role that Athinas St, in the main idea for the “Megalos Peripatos”, would play has already been filled and there does not seem to be a need for a second major pedestrian street.

We conclude that in the Historical Commercial Triangle of Athens, there is an economic inequality that leads to the partial decline of the area and the abandonment of many buildings: on the one hand, the small shops, craft shops and residences; on the other hand, the big shopping centers, the leisure activities, and the hotels that have been established and replaced the traditional uses. This current situation derives from socioeconomic and geopolitical reasons combined with the age and characteristics of historical buildings that make the adaptive reuse of said buildings more difficult.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, it is argued that the empty buildings of the area can be a great opportunity for the preservation and the development of this historical neighborhood, with proper preservation strategies and a sustainable Land Management. As cited in “The Leeuwarden Declaration: Adaptive Re-Use of the Built Heritage: Preserving and Enhancing the Values of our Built Heritage for Future Generations”:

“Through smart renovation and transformation, heritage sites can find new, mixed or extended uses. As a result, their social, environmental and economic value is increased, while their cultural significance is enhanced”.

The above problems of the area led to a series of proposals, which are described below. First of all, a key parameter for addressing them is the formulation of a policy aimed at preserving the historic multifunctionality and coexistence of different activities in the Historical Commercial Triangle [

1], in order to deal with the mutation phenomena of the diverse character of the area under the weight of leisure sub-centers and tourist activities (hotel units, short-term rental areas). According to our analysis, it is essential to publish legislation that focuses on a variety of uses that coexist in a harmonic and sustainable way. This cannot be achieved unless a strict plan is produced that defines the proposed uses per cent in every quarter (and not in the whole area). In this way, touristic and leisure activities will be reduced and shared all over the neighborhood, and not in specific sub-centers, such as Agias Eirinis square. In order to support the residency and the traditional commercial uses of the area, it is also proposed that an obligatory minimum percentage of these uses in every quarter is included in the ground floor uses plan, according to similar examples in other European historical city centers. These proposals should not be limited to a spatial approach, but also include an extended socio-economic and historical analysis of the neighborhood.

It is also proposed that a special team of engineers should be established in order to publish a detailed template with restoration guidelines, specifically for the historical buildings of the Historical Commercial Triangle. In this way, any restoration process will be easier and more efficient. It is very important that the restoration guideline focuses on the architectural value of the buildings, without failing to take into consideration how these buildings could be adapted to serve the current needs of people. This last point is especially important, as undoubtedly, many historical buildings remain abandoned due to their old structure that complicates any effort for the buildings’ adaptation to new, contemporary, uses.

In addition, we suggest the publication of a comprehensive traffic study, which will take into account the specific needs of all existing uses in the area and will indicate the correct arrangements concerning pedestrian streets, cycling routes, parking spaces and types of public transport. This part of the research should include all the neighborhoods around the Historical Commercial Triangle in order to conclude the most effective connection of the study area with the rest of the city. In the heart of the Historical Commercial Triangle, the streets are pedestrian, so special arrangements for the stores’ supply are needed. For the same reason, parking areas for the visitors and, most of all, the residents should be provided. A minibus in the center of the Historical Commercial Triangle is also proposed, in order to help the transportation of visitors, employees and residents. This study could supplement the latest complete master plan in Athens, which is the Athens/Attica Master Plan (AMP), [

19] established in 2014 as a strategic regional spatial plan, prescribes for Athens “maintenance and strengthening of the existing residency and development of a new one”, “maintenance of the social multi-collection” access by public transport (AMP, Article 6), “activation of the empty building stock” (AMP, Article 15), etc.

Furthermore, the current legislation is focused on the preservation of the exterior of many historic buildings, but this regulation, on its own, cannot prevent these buildings from abandonment. In reality, the more a building (or part of it) is abandoned, the more difficult and expensive it is for the owner to restore it. So, in the case of abandoned historic buildings, special financial incentives, such as special subsidies and tax discounts are proposed to cover their maintenance and restoration cost. As cited in The Leeuwarden Declaration: Adaptive Re-Use of the Built Heritage: Preserving and Enhancing the Values of our Built Heritage for Future Generations:

“To enable a re-use in the long-term, it is crucial to ensure that the preservation of heritage values is compatible with the economic requirements of the project (renovation, exploitation and maintenance of the building)” [

2] (p. 2). Financial support, such as tax and rent discounts, should be combined by promoting the desired uses: the re-establishment of permanent residency as well as the re-opening of traditional and craft shops. Regarding the owners of historical buildings that own low-rise properties, in particular the procedure of transfer of development rights is suggested [

36]. This legislation would concern historical buildings for which upward extensions are allowed. In order to avoid these extensions, owners would be able to restore or sell their buildings without adding any stories, in exchange for transferring the non-used building factor to another property they own.

It is also necessary to support all the above proposals with corresponding legal and administrative regulations and efficient control systems that will ensure compliance. As cited in The Leeuwarden Declaration: Adaptive Re-Use of the Built Heritage: Preserving and Enhancing the Values of our Built Heritage for Future Generations:

“The process of continuous analysis, selection and legal protection of listed buildings requires active attention from the competent public authorities, so that ambitions for adaptive re-use can be tested against the requirements arising from the legally protected status of heritage and integrated in a responsible manner”. [

2] (p. 2). In our case for example, according to the current legislation, nuisance produced by artisanship or leisure activities is forbidden during noon and night hours, but it seems that cafes and bars are not compliant to this legislation, since most of them are open all day long, playing loud music especially at night. As for the historical buildings’ front views, the owners are obliged by the Government Gazette 349D/1985 (FEK 349D/1985) [

34] to carry out repair and maintenance works every 10 years but, unfortunately, this rarely happens. According to this FEK, many historical buildings are protected in the Historical Commercial Triangle. There are also specific registrations for the construction of additions in the historical buildings, for the building factors, and the maximum number of building stories (4–5 stories). It is obligatory for the owners of the historical buildings to maintain their facades every 10 years (Article 5). It is forbidden, in any case, for the uses in the neighborhood to be disturbing for the environment, the traffic, and the residency (Article 6) [

34].

To ensure that plans would be implemented effectively, preservation strategies should be integrated in a management plan accompanied by the establishment of a local administrative office, specializing in the preservation and protection of the Historical Commercial Triangle. Its main role would be to ensure compliance with the regulations, and to deal with problems that show up. This would help the elimination of the empty buildings (or part of them) and the restoration of the historical buildings, as the office would also be responsible for seeking funding programs and always be in close contact with different stakeholders, working as a link between owners, residents and the government (especially the Ministry of Culture, Environment, etc.). As cited in The Leeuwarden Declaration: Adaptive Re-Use of the Built Heritage: Preserving and Enhancing the Values of our Built Heritage for Future Generations:

“Responsibility for re-imagining our built heritage is shared by many stakeholders. Multidisciplinary teams are needed, working in a collaborative manner from the very beginning of the project, in order to discuss technical, economical and legal possibilities and resolve possible contradictory interests”. [

2] (p. 2).

In this context, it is crucial for a local community assembly to be established, involving all relevant actors and stakeholders, from employers and employees to residents and building owners (

Figure 24). The role of the assembly would be to create a space where these actors can discuss their concerns and the problems they identify in the area, aiming to ensure their harmonious coexistence and enhance the neighborhood’s development through time. As cited in The Leeuwarden Declaration: Adaptive Re-Use of the Built Heritage: Preserving and Enhancing the Values of our Built Heritage for Future Generations:

“Consulting citizens is a good way of gaining support for financial investment and ensuring that a project will match the needs of the local population. Such debates boost social interaction and society’s responsibility for local cultural heritage”. [

2] (p. 2). In these meetings, discussions could revolve around the participants’ ideas and perspectives on the upgrade of the Historical Commercial Triangle, through various strategies, such as the reuse of empty buildings for cultural purposes. These two proposals will contribute to the long-term harmonic coexistence and development of this historical neighborhood.

In this article, we provided an analysis of the problems presented in the Historical Commercial Triangle of Athens and outlined a proposal of corresponding strategies to address them. These strategies highlight the need to preserve the history and the multifunctionality of the area, as it is argued that the diversity of uses is what ultimately defines the true value and character of an area and ensures its sustainable development. It is supported that the development of this part of the historic center of Athens that has been abandoned in the last decades can be achieved only if the traditional and new uses manage to coexist sustainably, in an upgraded public space adapted to the needs of the contemporary city. To construct that proposal, it was essential at first, to recognize the necessity of a strategy based on the concept of multifunctionality, as opposed to the monoculture of specific sectors. Ultimately, in all cases, it seems necessary that policies proposed for protection and development through reusing abandoned buildings or parts of buildings must always approach the space in a holistic way, and the formation of strategies must cover the whole spectrum of life, concerning all the tangible and intangible components that define the identity of an area.

The above proposals for the preservation and sustainable reuse of degraded or abandoned historic cities’ parts could be seen as a modern approach that emphasizes interdisciplinary and multispectral collaboration while giving priority to the residents and employees of the area. In this case, an ongoing dialogue is proposed between engineering professions, such as architects and civil and surveying engineers, together with professions of the humanitarian fields, such as archaeology, sociology and tourism, and the fields of economics, administration, and politics. Moreover, the proposed strategies could be further developed using modern technological advancements. More specifically, the final map (

Figure 25) containing the strategies and sub-proposals could be digitized to provide an interactive guidance model on handling the issue of reuse. This map could be published on an open-access platform, created by the special engineer team, the special administrative office and the corresponding ministries, which would receive all the comments of the local actors about the problems, the alterations of the area as well as possible proposals. This can be seen as a real-time feedback tool that ensures the involvement of all stakeholders, as this would help to better understand and engage the local community, which is essential for any successful strategy.