1. Introduction

The cities of Santo Domingo (1502) and Panama Viejo (1519) are part of the first urban experiences of Spanish colonization in America. After the discovery of America in 1492, the first foundations emerged in the Caribbean Sea region. First came Santo Domingo on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola—an island currently made up of the countries of Haiti and the Dominican Republic—being the oldest colonial settlement in America, while Panama Viejo was the first city founded in the American Pacific.

Authors who have studied Ibero-American colonial formation—such as Benévolo [

1], Medina [

2], and Hardoy [

3], among others—make clear the complexity of stating what the influences of the New World’s urban layout are. For this article, the geographical conditions of the environment will be taken into account as one of the determining factors in choosing the location. In this sense, the maritime connection was vital, with the port being a key piece for commercial transport with Spain, as well as a point of defense for the city.

The uses and typologies of buildings should also be mentioned; on the one hand, government buildings such as the City Council, Royal Houses, or Royal Audience would be placed at a point near the port and the Plaza Mayor and, on the other hand, monastic buildings with the arrival of the religious orders to the colonies. We will study the latter architectural typology in this article since the construction of decentralized religious buildings played an important role in the urban evolution of cities.

Among these religious buildings, we highlight the role of convents and hospitals as key pieces in the composition of the urban footprint of cities thanks, in addition to their architectural scale, to their location on the outskirts, away from central areas. This led the population to prosper around these areas, serving as nodes of urban expansion.

The objective of this article is to compare the process of formation and evolution of the colonial cities of Santo Domingo and Panama Viejo, analyzing the foundations of religious buildings and the impact on the morphological evolution of these cities from an urban perspective.

As a methodology, we first carried out the analysis of the cartography and historical bibliography, as well as recent studies on the urban evolution of these two cities. This allows a characterization of the original urban layouts; the study of their chronology, transformation, and growth; and the hierarchy of their different spaces, especially including their link to the conventual architectural typology. For this, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) have been used, standardizing graphic visualization and generating comparative maps, as we will see below.

Finally, we carried out a comparative analysis between the two case study cities of Santo Domingo and Panama Viejo through three stages of expansion chosen by the authors, considering both the available historical cartography and the different hypotheses of growth, such as the founding dates of the religious buildings studied, until the consolidation—or destruction as we will see in the case of Panama—of these cities, which are paradigmatic in the study of early colonial urbanism.

2. Theoretical Model of Early Colonial Urbanism

The ordinances, instructions, or laws issued by the Spanish kings were delivered to some discoverer or conqueror with whom the Crown signed an agreement to organize the new territories in America [

4] (p. 50). Although the first Ibero-American settlements were founded with instructions, they had little or no influence in practice due to their vagueness. Even so, it is considered important to mention the state of the art at the time that Santo Domingo and Panama Viejo were established.

Jaime Salcedo [

5] (p. 26) calls the period of Christopher Columbus’ arrival “the factory or Columbian factory” because it was based on the commercial monopoly between Columbus and the Crown. As for the cities founded during this period, they did not resemble the Spanish or the American ones; they were mere commercial enclaves.

The first instructions, given in 1501 to Nicolás de Ovando—governor of Hispaniola—were very generic, leaving the foundation of the cities to free discretion [

3]. Hardoy [

3] (p. 3) reinforces this theory, explaining that: “during the first few decades, the instructions were almost always vague and based on the experiences of the discoverers and conquerors or included directives so general and obvious that they had already been taken into account without the need for royal orders,” just as Martínez Lemoine expresses that it was the conquerors who provided the greatest criteria for the urban design of the first cities: “it follows that there were no previous instructions and that this transposition would derive from personal experience.” [

6] (p. 11).

Later, the Instruction of King Ferdinand the Catholic (1513) arose. This Instruction given by the king to Pedrarias Dávila [

7] (pp. 342–353), although not very specific, represents the establishment of a settlement and colonization policy, the first of its kind and an example for the future [

8] (p. 33). It is one of the first writings that specifies how to urbanize the new territories.

Therefore, in these years, we can see an initial evolution in the city model that ended with the grid and developed the subsequent systematization of urban typologies [

9] (pp. 25–26). This systematization is similar to the model mentioned by Hardoy, which is characterized by an orderly but irregular layout, a square—not necessarily central—with its main buildings around it (usually the cathedral, the town hall, or the government house) [

3]. This description can be used to understand early colonial urbanism.

3. Early Colonial Urbanism: The Cases of Santo Domingo and Panama Viejo

3.1. Foundation of Santo Domingo (1502)

The first settlement of Santo Domingo—founded by Bartholomew Columbus in 1496 [

5]—was destroyed by a hurricane, and its governor—Nicolás de Ovando—rebuilt the city on a nearby site. The layout of Santo Domingo by Ovando (1502) marked a surprising action for his contemporaries; the city was founded with a clear knowledge of the resources and characteristics of the region. The urban layout takes advantage of the geography, following the northwest direction parallel to the Ozama River and the Caribbean Sea, which, together with the rugged topography of the north, made the city easily defensible, with only one side (the west) to protect and expand by land [

3].

According to Salcedo [

5], Nicolás de Ovando sought to create a colony according to the Castilian model. He distributed land to the settlers on the condition that they reside on it and make it produce, and he awarded them urban plots, allowing them to search for gold on their own initiative, paying the corresponding taxes to the Crown; these were aspects that the Crown would take into account in the instructions for Pedrarias. It laid the foundations for the policy for the settlement and colonization of America and gave an order to the cities he founded, the most important being Santo Domingo.

It is worth emphasizing the importance of good street design in this city, with late medieval reminiscences [

3]. According to the chronicler Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo, the layout of Santo Domingo “is much better than that of Barcelona, because the streets are so much flatter and incomparably straighter” and “it was laid out with a ruler and compass and all streets follow the same measure.” [

3]. Its layout sought order, but it did not come to reflect a grid.

Equally striking is its peculiar “

place excentre”, according to Erwin Walter Palm [

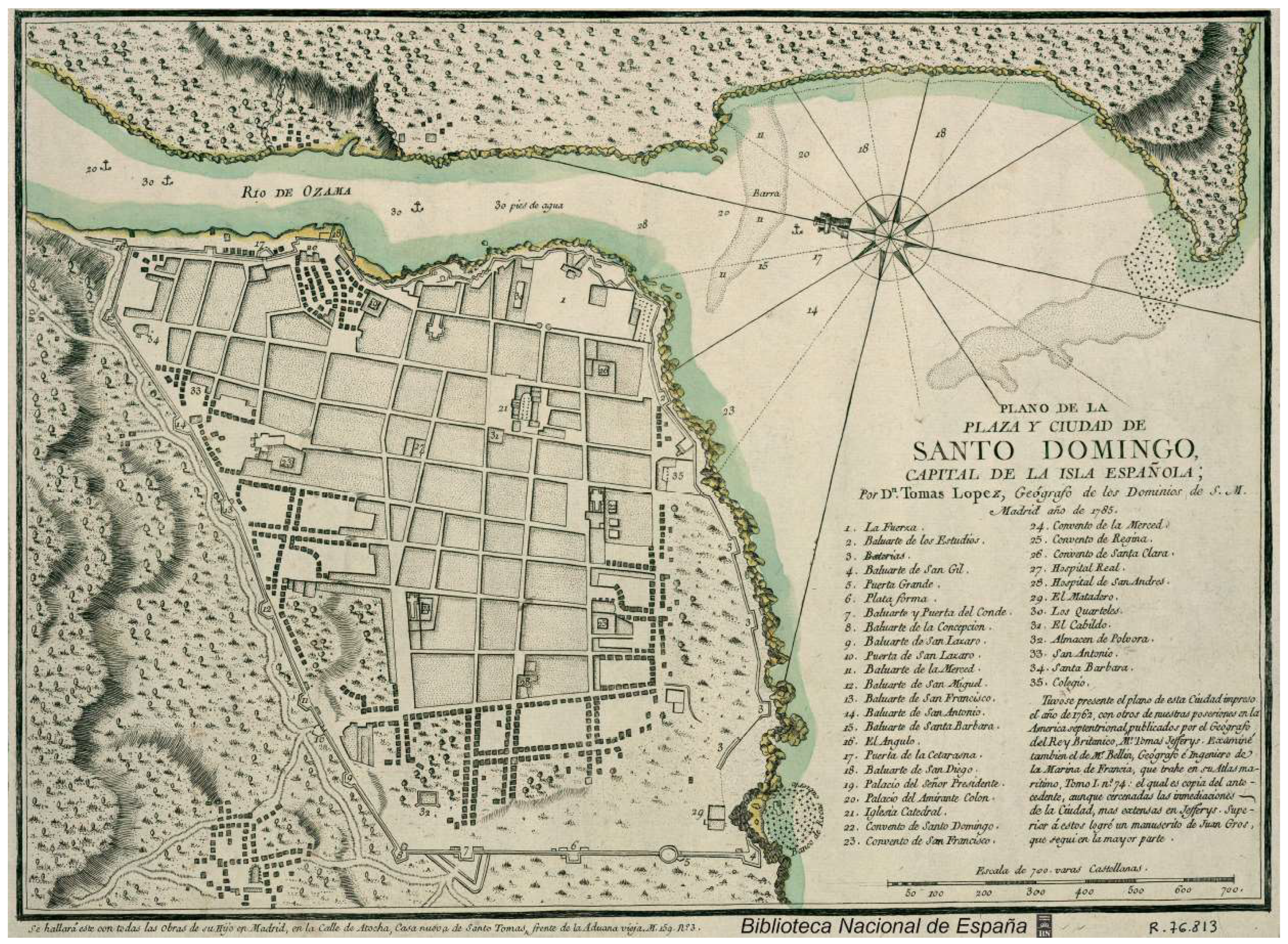

10] (pp. 46, 55). On the map (

Figure 1), we can also see the importance of religious buildings in the urban fabric of the city, which we will explore later.

3.2. Foundation of Panama Viejo (1519)

Before the founding of Panama Viejo, Vasco Núñez de Balboa founded St. Mary the Old of El Darien (Santa María la Antigua del Darién) in 1510, now part of Colombia. Here, the Franciscans founded their first modest convent, and the first diocese of the continent was created, building the first cathedral at the request of the Crown in 1513, assigned under the metropolitan see of Seville until 1541 when it passed to the jurisdiction of the Archbishopric of Lima [

11]. The history of this city is short, since nine years later, with Pedrarias Dávila as governor, it was decided to move this settlement to the so-called South Sea (now the Pacific) and found the city of Our Lady of the Assumption of Panama (Nuestra Señora de la Asunción de Panamá), known today as Panama Viejo, in August 1519.

Following the king’s instructions to Pedrarias, the city was built next to the sea, between the Gallinero River to the east and the Algarrobo ravine to the west [

12]. At first, an orderly layout is observed in terms of streets and lots, although given the conditions, a perfect grid was not followed. It has been possible to verify through cartography and in the field that the streets were not straight and the blocks were of different sizes. To the north (the only area of expansion), the city became even more irregular, with trails following the topography of the area.

There is no foundation charter or foundation plan, so it is believed that the first thing that was designed was the Plaza Mayor—completely eccentric—just as in Santo Domingo. Castillero Calvo [

13] (p. 120) mentions, as does Mena García [

8], that “the regulations that governed settlements established that when port cities were founded, they should have a square by the sea.”

The city was laid out taking into account the port to the northeast and the hill to the southeast, leaving room for a fortress. It was extended towards the north, as far as a lagoon allowed, and towards the west. The Convent of Mercy (Convento de la Merced) was located in that direction as of 1522 (the first to be established in Panama), to whom a site was officially granted as of 1540. In addition to this, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo describes a long and narrow city in 1529 with dwellings facing the city and the sea behind them [

14].

In

Figure 2, we can see the consolidated city forming that rectangular layout in an east–west direction, with the project of a future wall that was never built. Here we can also see the religious buildings stand out within the urban fabric of the city.

The discussion about the regularity or irregularity of the urban layout of the city of Panama Viejo was initially based on cartography. The first known plan of the city in contemporary times was the “Plan of the City of Panama and the site where the Royal Houses and Perico and other islands are” of 1609, which was attributed to Cristóbal de Roda. Later came the “Plan & prospective of the City of Panama” of 1586, attributed to Bautista Antonelli (

Figure 2) and released at the end of the 1980s [

8] (pp. 116–117).

Regarding these two very different maps, it can be explained that the one from 1586 shows a layout where the streets are not straight, and the blocks are irregular in size, while the one from 1609 shows straight streets and quite regular blocks. It is very likely that the research carried out on the layout of Panama Viejo before the 1980s was based on this image of the city. Likewise, it is important to point out that Panama City (known as Panama Viejo, 1519–1671) was often confused with its second location after the transfer (1673 onwards): the current Historic District of Panama City.

4. Influence of Conventual Architecture on the Urban Layout

It was in the mendicant orders that the responsibility for the evangelization and Christianization of the indigenous people of the New World fell; therefore, they initiated the construction of the ecclesiastical buildings unquestionably supported by the Spanish Crown since the constructive activity was of vital importance for the consolidation of the colonies.

Religious buildings, with the exception of cathedrals—always located next to the Plaza Mayor and the City Council in a central location—are going to have a common denominator since monastic buildings and hospitals are going to be built at the farthest ends of the town [

15], marking the limits of the growth of cities, as we will see in the cases of Santo Domingo and Panama Viejo, and as was being done in Europe before this [

16] (p. 23). While close to the port, this is where all the commercial activity was concentrated—Royal Houses, Royal Audience, or the shipyards—around the convents and temples, giving rise to centers of population attraction, since in addition to ecclesiastical and oratory use itself, they generated work in their gardens, kitchens, and stables [

17] (p. 2), which ended up giving rise to the different neighborhoods of the city and, therefore, its urban expansion.

Located on the outskirts, convents also served as points of control and defense of the cities, as they were also closed structures or protected by perimeter fences. In addition to this, it is possible to mention the appearance of squares in front of the churches of the convents, where daily life was carried out, and which were the scene of religious festivals and activities [

16] (p. 23). Both phenomena make up the structure of the public space in colonial urbanism, giving rise to a very important relationship between this architectural typology and the origin of the urban layout.

4.1. Religious Buildings in Santo Domingo

4.1.1. First Stage of Study (1502–1525)

This first stage coincides with what is known as the “Ovandina stage” or the “city of Ovando,” the period in which Nicolás de Ovando ruled (1502–1509) and when the first steps were taken in the configuration of the urban structure of the city of Santo Domingo [

15] (p. 125).

Although the first missionaries of the Franciscan Order arrived in 1493 together with Christopher Columbus on his second voyage, they still had no intention of settling in the New World. It was in 1502 when a new group of Franciscans arrived alongside the governor with the aim of establishing the Order in the Caribbean, which was succeeded shortly after by the Dominicans, Mercedarians, and Hieronymites [

18]. All these orders settled on the island, and each one began to build their respective convents and churches.

The first was the Convent of St. Francis (Convento de San Francisco)—the first convent founded in all of America—beginning its construction in 1502. The building was initially built out of wood on top of a hill in the extreme north of the city, which was a strategic point to see the entire territory. In 1543, the stone works began, which were ultimately concluded in 1664 after several setbacks.

The Dominican friars also began the construction of their convent very early (1510), concluding it around 1535. Shortly after, they decided to expand the complex, including the site where the first university in America was housed: St. Thomas Aquinas (Santo Tomás de Aquino), founded in 1538 [

15] (p. 155).

Finally, it is worth mentioning the third point of importance on the outskirts of “Ovandina city,” which would be the Hospital of St. Nicholas of Bari (Hospital de San Nicolás de Bari), founded in 1503 by the same governor [

19], which is the oldest in America.

Looking at

Figure 3, which shows the arrangement of these three religious buildings on the western edge of the city, the side where it would end up expanding later, we see the clear relationship of this architectural typology as spatial control of the city and, as we will see below, serving as nodes of future urban expansion.

On the other hand, it is worth mentioning the construction of the Cathedral of St. Mary of Incarnation (Catedral de Santa María de la Encarnación), also the first foundation of its kind, first made of wood and straw in 1502, then stone from 1521 until its consecration in 1540, which was built in a more central position next to the Plaza Mayor. At the urban level, the cathedral was an exception in terms of the functioning of religious buildings as nodes of urban expansion in the periphery since was always be linked to the location of the Plaza Mayor [

15] (p. 129). This functional duality between the location of the convents, hospitals, and hermitages with respect to the cathedral was a constant in all the colonial foundations.

4.1.2. Second Stage of Study (1526–1540)

Although there is not much certainty about the exact date of the Mercedarians’ arrival, we do know that the beginning of the construction of their convent in 1527 by the Spanish architect Rodrigo de Liendo—who also began the construction of the wall of the city in the mid-16th century—marked the first expansion of the city towards the west, continuing a main axis of the city that came from the Royal Houses and the port, passing through the Hospital of St. Nicholas, giving rise to Merced Street. The convent was completed in 1555, and the church was also known as Mother of God (Madre de Dios) [

15] (p. 156).

In

Figure 3, we can see how once again, the new conventual foundations, in this case, the Convent of Mercy, are located on the edge of the colonial city, always seeking this territorial control.

4.1.3. Third Stage of Study (1541–1805)

In this period, the female orders arrived in Santo Domingo. First, the Clarisses belonging to the Franciscan Order founded the Convent of St. Claire (Convento de Santa Clara) in 1552. Later, the Dominican nuns established the Convent of Regina Angelorum in 1560, surrounded by the convent of the friars of their same order. Both convents consolidated the city on the south side towards the Caribbean Sea.

The Hospitals of St. Lazarus and St. Andrew (Hospitales de San Lázaro and San Andrés) were also built between 1560 and 1562, with their corresponding temples, in the extreme west of the city. Despite being less relevant, it is also worth mentioning the construction of certain hermitages such as St. Anton or St. Barbara (Ermitas de San Antón and Santa Bárbara) and parishes or small churches such as Our Lady of Remedy or Our Lady of the Carmel (Nuestra Señora de Los Remedios and Nuestra Señora del Carmen) on the edges of the city.

Table 1 shows the summary of all the religious constructions mentioned.

This last stage, of less importance as far as conventual foundations are concerned (since most of them were built in the 16th century), is important for the culmination and consolidation of the urban fabric, as well as the completion of the wall—after more than two centuries of construction—towards the end of the 18th century. We can see how there are religious buildings close to this entire walled perimeter.

To conclude, the map in

Figure 4 shows the decentralized location of religious buildings, though connected through the main streets both in an east–west direction (Merced or Regina-Santa Clara streets) and north–south (San Lázaro, San Andrés, San Miguel, and San Francisco streets). Religious buildings gave names to secondary streets, reinforcing their importance for the city.

4.2. Conventual Foundations in Panama Viejo

4.2.1. First Stage of Study (1519–1540)

Like other cities founded in the New World, the start of this new city was modest, and its growth was slow. The first constructions were all made of wood, then were gradually consolidated as they passed to masonry.

The first convent to be built was the Convent of Mercy of the Mercedarian friars, who arrived on the isthmus in 1522 and obtained a spacious site located in the extreme west, near the Matadero stone bridge and the Fort of the Nativity [

12], points of defense and control of the city. The Mercedarian friars, in addition to attending worship in their church, performed military services as chaplains in castles and military fortresses [

20] (p. 151). Perhaps, for this reason, they were located in this unique settlement away from the city center.

As we commented for Santo Domingo, in contrast to the decentralized location of the convents, in Panama Viejo, the cathedral is also built in a central position next to the Plaza Mayor, following the recommendations cited in the instructions from the Spanish Crown. After the transfer of the diocese to Panama in 1524 [

8] (p. 156), the first references to the cathedral were between approximately 1526 and 1530 [

21] (p. 69), although it was not until 1540 that the construction of the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Assumption began.

As can be seen in

Figure 4, in the first period of growth of the city between 1519 and 1540, it was already possible to observe how the urban design was formed by an elongated rectangle that ran from the port to the east, passing through the Plaza Mayor-cathedral until reaching the Convent of Mercy to the west. Its main street was probably Carrera Street, parallel to the Pacific Ocean.

4.2.2. Second Stage of Study (1541–1586)

The Dominican friars, although they were on the first expedition to the South Sea [

12] (p. 19), first settled in Name of God (Nombre de Dios) in 1510, a precarious port settlement near Portobelo, founding their first convent there in 1519 and operating under the jurisdiction of the Spanish province of Seville until 1530. In 1565, they decided to move to the prosperous city of Panama, following in the footsteps of the urban and social development of the government [

22], before said settlement was razed to the ground and abandoned in 1572. In 1571, the Convent of Santo Domingo was founded in Panama, north of the Plaza Mayor. It began as one of the most modest in the city made of wood, although with its transition to masonry at the beginning of the 17th century, it was among those that best withstood the 1621 earthquake.

The Franciscans also first began their conventual foundations on the Caribbean coast, founding the aforementioned monastery in St. Mary the Old of El Darien (the first “mainland” conventual foundation). Around 1552, there were the first references of Franciscans in the new Panamanian city of the Pacific [

12] (p. 18), although due to the scarcity of means, it was not until 1573 that the Convent of St. Francis intensified its construction. By 1586, the construction already occupied 45% of the site [

23] (p. 744), and it was built little by little until its completion at the beginning of the 17th century.

The Hospital of St. Sebastian had a similar history to the Franciscan convent. First, they founded a hospital in El Darien; then they moved to Panama Viejo. There are references to the fact that there was a modest hospital made of wood in the early years of the city, although it was not until 1575 that they got enough money to buy the site that is now occupied by its ruins on Carrera Street, facing the sea. It continued to operate until 1620, when it was occupied by the monks of the order of St. John of God (San Juan de Dios), to which they owe the current name [

24] (p. 70).

The Convent of the Society of Jesus (Convento de la Compañía de Jesús) was founded in 1578 [

12] (p. 20)—one of the last to be founded—and for this reason, it was decided to place it closer to the Plaza Mayor since the city no longer had the intention of expanding further. For a long time, it was made of wood, and it was not until the beginning of the 17th century that the convent slowly began to be rebuilt with stone and masonry structures.

Finally, it is worth mentioning the construction of two hermitages in the mid-16th century. Although they do not have the same relevance at the urban level, their location on the outskirts reinforces the decentralized role of religious constructions. First, the Hermitage of St. Anne (Ermita de Santa Ana), erected around 1568, was located on the extension of Santo Domingo Street, near the Rey bridge, the northern access point of the city [

21] (p. 115).

The Hermitage of St. Christopher (Ermita de San Cristóbal) must have been built around 1575 on the hill which received the same name. From its summit, the entire city, the surrounding mountains, and the entire bay could be seen [

21] (p. 113).

This was the period of greatest splendor as far as religious constructions are concerned. As has been seen both in Antonelli’s plan (

Figure 2 and

Figure 5), the city is practically consolidated.

4.2.3. Third Stage of Study (1587–1610)

The architectural complex formed by the Church and the Convent of the Conception (Convento de la Concepción) was the seat of the only female religious congregation that was implanted in Panama Viejo in 1598, one of the largest in the city. Unfortunately, it was destroyed in the 1621 earthquake. Its reconstruction began in 1640, although it was never finished.

Finally, the Augustinian fathers founded the Convent of St. Joseph (Convento de San José) at the northern end of Panama Viejo. It was built around the middle of the 17th century. It was the last of the conventual buildings established in the city between 1604 and 1610, although it was still under construction between 1615 and 1620 when the earthquake occurred. See in the

Table 2 below the foundations chronologically ordered.

In the case of Panama Viejo, the streets were clearly marked by the plots that make up the religious buildings in the city, starting in the form of an “L” parallel to the water from the Plaza Mayor, both to the north to Santo Domingo and to the west to Mercy. We can see the main streets at their time of greatest expansion in

Figure 6.

(E–W) Carrera or Real Streets: It was the main thoroughfare of the city; it allowed entry and exit of the city via the Matadero bridge. Merchandise that came from the west of the isthmus and Europe also entered using this road, via the Cruces road, from Portobelo to Panama. It connected the Mercy and St. Francis convents and the Hospital of St. John of God.

(E–W) Empedrada Street: This street, which emerged later, also connected the main religious buildings, from the Plaza Mayor with the cathedral to the Convent of St. Francis, passing through the Convent of the Conception and Society of Jesus and also the Hospital of St. John of God. It owes its name to the fact that most of its route was cobbled.

(N-S) Santo Domingo Street: Its name comes from the fact that it was the street that went from the Plaza Mayor to the Convent of Santo Domingo heading north. This road reached the Rey bridge. From there, Real Street was taken, which connected the city with Name of God and Portobelo to the north of the Isthmus of Panama.

Most of the convents were left in ruins after the earthquake of 1621. Following the subsequent fire in the city due to the attack of the pirate Morgan in 1671, the city decided to move to the current Historic District of the city. Therefore, the city of Panama Viejo had only 152 years of history (1519–1671), so it is assumed that it did not have time to finish consolidating a large part of the projected city, in contrast to Santo Domingo. It should be noted that a large part of the remains of the buildings in Panama Viejo was used as a quarry for the reconstruction of the new city, even in the case of some religious buildings that were not greatly affected, which were rebuilt in image and likeness, such as the case of the Mercy Church.

5. Results & Discussion

After carrying out the comparative analysis between both case studies through their three evolutionary stages, we were able to more clearly perceive the relationships between their functional structures and their urban designs.

In Santo Domingo, it can be seen that from the first stage of foundation studied, there was already a clear idea of order. In this context, and following the recommendations given in the Crown’s instructions to Ovando, it was decided to insert the cathedral in a central position next to the Playa Mayor. This model will be replicated in all cities. On the other hand, the rest of the religious buildings, among which the convents stand out, are located within the limits of the mesh, serving as a spatial control mechanism since the city was limited to the south by the sea, to the east by the river and the north by the topography. As soon as the grid was expanded, the religious buildings followed the same function of delimiting the urban layout, serving as nodes of urban expansion. On the map of the city consolidated in 1805 (see

Figure 3), the religious buildings can be seen surrounding practically the entire previous layout.

Something similar occurs in Panama Viejo, although due to the fact that the city did not manage to expand as much, especially due to its geographical or natural limitations [

14], the scale of the intervention is smaller. Therefore the grid conception is less obvious compared to Santo Domingo. In the early years (see

Figure 4), the cathedral is also seen to be located in the Plaza Mayor, and from this point of intersection, the main axes depart both to the north and to the west, where the religious buildings will be located. In this case, the convents also serve as a delimitation of the colonial urban space, having been placed on the outskirts of the city. However, they did not serve as expansion nodes but rather as nodes of geometric consolidation of the existing plot, shaping the streets and plots that we know today.

In short, in Santo Domingo, the religious buildings were placed on the edges of the mesh, and from there, the city formally grew through them. Meanwhile, in Panama Viejo, the religious buildings regularized the interior of the mesh once the limits of the city were established. Therefore, both cases played a very relevant role in the evolution and consolidation of the urban fabric. However, the case of Santo Domingo, perhaps because it had a longer history, is closer to the theoretical model of the colonial city that became effective in the future (see

Figure 7).

On the other hand, it is worth noting the role of religious orders in shaping cities. Upon analyzing the chronology of the arrival of each order and the years of foundation of each convent, it is significant to mention that the Franciscans, Dominicans, and Mercedarians were the first three orders to found their respective convents in both cities, choosing enclaves that would mark the growth of the cities.

As we can see in

Table 3, the Franciscans and Dominicans follow a logical chronology similar to the emergence of both colonies, first going to Santo Domingo and then to Panama Viejo. However, the Mercedarians founded their convent in Golden Castille (Castilla del Oro) rather than in Santo Domingo.

If we cartographically analyze the location of these three convents in both cities at the time the last one was built, we can see how these three foundations mark the limits of the city, both to the north and to the west (see

Figure 8), settling on the outskirts, as happened in the old European cities [

16] (p. 23).

6. Conclusions

We have been able to verify that the instructions of the Crown did not play an important role in the design of the first Latin American cities. In this context, the distribution of uses and functions in the cities and their dialogue with the topography and the natural characteristics of the territory turned out to be more important in the construction of the colonial urban space.

The comparative study of urban construction in the colonial cities of Santo Domingo and Panama Viejo, observing the role of religious institutions, showed two different positions in the formation of their urban layouts.

In the city of Santo Domingo, the search for regularity in its layout is perceived, with the distribution of streets relatively organized around the structuring axes of the city. Its Plaza Mayor appears as a distribution point for its streets and expansion axes. This logic becomes the embryo of what would later become extreme orthogonality—the checkerboard with a central square—applied in hundreds of colonies spread across the American continent. However, the existence of two centralities—the port and the main square, both eccentric—distances the proximity of the urban structure of Santo Domingo from the concentric logic applied later.

The idea of the formation of the city of Santo Domingo in a mesh (albeit imperfect) is reinforced when we observe the position of religious institutions: in the three evolutionary phases observed, they were uniformly distributed along the perimeters of the city, marking the expansion axes as an instrument of control and consolidation of an urban layout. There is, therefore, no sense of main streets or concentration of religious power in a single area of the city.

The city of Panama Viejo, for its part, was based on a linear logic of composition. It was founded in a square very close to the port, where its administrative activities were concentrated. From there, it developed an L-shaped design, where a street defined the longitudinal feature of the city’s layout. In this context, convents and other religious buildings emerged as consolidating elements of the structuring axes. The streets occupied by the convents became the main streets of the city and defined the formation of its urban design.

This paper sought to demonstrate the importance of the role of religious power in the formation of the cities presented here. Finally, it is presented as a methodological possibility to continue with other case studies in the search for the definition of the structuring relationships between religion and urban form in the Ibero-American colonies.