Intricacies of Moral Geographies of Land Restitution in Estonia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Brief History

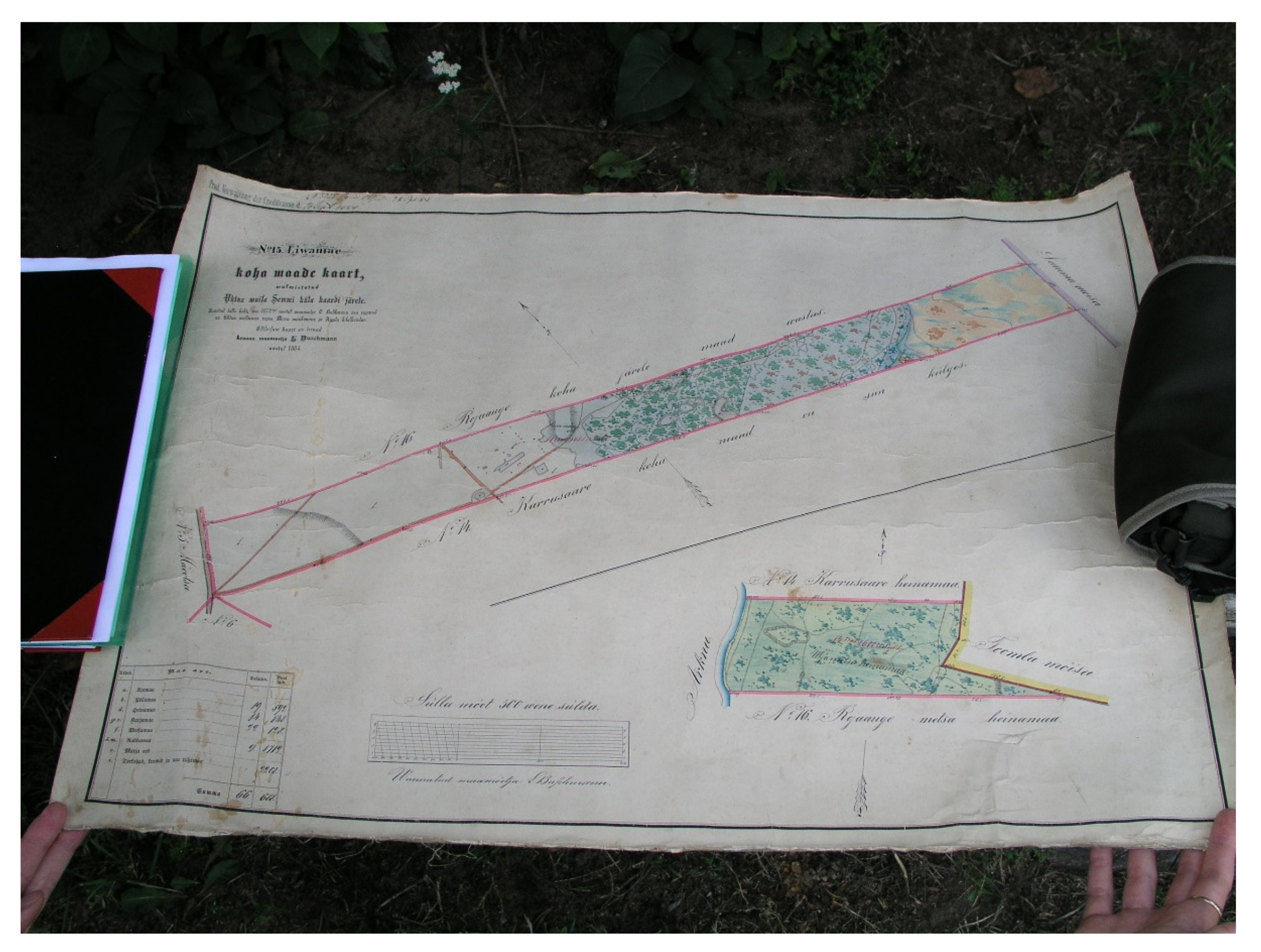

… people who owned land before the Soviet occupation kept track of the officially annulled pre-Soviet land rights, by relating to inertial landscape elements as memory-aids (Figure 2). To local inhabitants the landscape, in which past and present structures always merge, provided substantial evidence in support of the idea of legal continuity of pre-Soviet land rights. Hence, the post-Soviet land restitution reform often implied a re-discovery or re-expression of property rights that had been silenced, but not lost.

2. Moral Geographies of Land

3. Land Restitution Process

3.1. Parliamentary Debates

3.2. Processing Experiences

When we started to deal with applications, the municipality did not have special rooms for client service. We had regular office rooms, corridors, halls, where people had to wait and it was quite tough for them. But also for those, who dealt with applications /…/. We had some application forms that we had to fill in by hand, and we did not have any copy machines for copying, but just some pre-filled-in forms, which were copied by hand, using a special tracing paper, to make several copies. The entire process was rather time consuming and exhausting. People were drained… (Estonian National Museum Archive, ERM V 882:4).

At that time, old farm masters were still alive, they remembered their cattle and where their land had been /…/ and finally there was a time when people who wanted, got their farm back. /…/ We gave everything back, we found new living spaces for the ones who had been living in the houses in the meantime. I dealt with it as chair of the kolkhoz (Estonian National Museum Archive, ERM V 882:6).

3.3. Representations of Disappointments

When there is no law, there is nothing. /…/ [The law] should give security for a farm. /…/ At first, a secure land reform. At the moment I cannot do anything I want, though this land has been given to me to use.

I would need some clarity and perspective. Should we expand or not. Are we [the farmers] needed or all the crops will be imported. The land reform has been prolonged for too much, it’s hard to know, what comes, what stays, too many loose ends. It is damn hard right now. It is indeed hard. No perspective, I wouldn’t recommend it to [my] children.

I have been here for 50 years and we have built all this up, and repaired and taken care of… and now they come, all of a sudden and. … /.../ By force, in secret, they fix up the papers and they come now and come, forcefully taking this away.

We outlived the German and Russian government, but not this one. Land tax, social tax, income tax, traffic insurance…

Alimony for living, which is not even enough for dying….

Petrol is too expensive. The arable land is uncultivated, full of weed and bush. The state does not buy our crop. /…/ I give my wheat to pigs, but the state imports wheat. The loan interest is 40. The farms were supposed to be freed from tax for five years, but then taxed nevertheless [62] (p. 62).

Well, there are smart and successful people in rural areas, too. For instance, this house with a red roof, just some kilometres away from here. Newly built arch hall, new stable and barn. The yard is full of all kinds of machinery.

Oh that. /…/ This is a city guy, that’s why he is so smart and successful. People say he worked in some kind of ministry.

A crook is he, not a smart one! It’s easy to be successful, if you are in such a position, just say a word and everyone brings you what you ask for, no matter whose property, from kolkhoz or sovkhoz [62] (p. 101).

4. The Outcome

Modern Developments

5. Conclusions

Law, including customary law, is significant for the shaping of landscape; the earliest meaning of the term ‘landscape’ is linked to the role of legal institutions. Law and landscape are in turn both shaped by conceptions of justice, as well as by contestations over what is considered just and unjust in different societies [48] (p. 1).

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | In the Soviet Union, after a person graduated university or vocational school, they were assigned to employment in different parts of a given Soviet republic, or to another part of the USSR altogether. The graduate had to work at this job for a certain number of years before they could move on. In Estonia, where the language of study in the majority of universities was Estonian, post-graduation employment assignments usually remained within Estonia, apart from certain strategic subjects (e.g. geology), especially if the student had studied in Russian. |

| 2 | The stenograms of the Estonian Parliament sessions that form the basis of this analysis are available at https://stenogrammid.riigikogu.ee/et (accessed on 30 December 2021). |

| 3 | In Estonia, National Capital Bonds (NCB), known as ‘yellow cards’ after their yellow appearance, were introduced initially in 1993 to enable people to privatise their dwelling rooms. The NCBs were distributed to all permanent Estonian residents who were at least 18 years old in 1992. The value was calculated based on employment period in Estonia (1945–1992). Everybody was given NCBs for at least 10 years regardless of their actual employment years. There were certain bonus years for those politically repressed, orphans and parents. As what could be done with the NCBs was unclear, at some periods their value was very low, causing some speculative deals. The NCBs were inheritable. While initially meant for privatisation of dwellings, the bonds soon acquired wider usage and enabled all kinds of privatisation, including land and collective farms, until the end of 2006 [66] (p. 28). |

References

- Hull, S.; Babalola, K.; Whittal, J. Theories of land reform and their impact on land reform success in Southern Africa. Land 2019, 8, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Meitzner Yoder, L.S.; Joireman, S.F. Possession and precedence: Juxtaposing customary and legal events to establish Land Authority. Land 2019, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mutu, M. The Treaty Claims Settlement Process in New Zealand and its impact on Māori. Land 2019, 8, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stubblefield, E.; Joireman, S. Law, violence, and property expropriation in Syria: Impediments to restitution and return. Land 2019, 8, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wynyard, M. ‘Not one more bloody acre’: Land restitution and the Treaty of Waitangi Settlement Process in Aotearoa New Zealand. Land 2019, 8, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tamm, M. In search of lost time: Memory politics in Estonia, 1991–2011. Natl. Pap. 2013, 41, 651–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troska, G. Eesti Külad XIX Sajandil; Eesti Raamat: Tallinn, Estonia, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Giovarelli, R.; Bledsoe, D. Land Reform in Eastern Europe: Western CIS, Transcaucuses, Balkans, and EU Accession Countries; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Seattle, WA, USA, 2001; Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/ad878e/AD878E00.htm#toc (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Terk, E.; Järvelaid, P.; Kivirähk, J.; Saar, I.; Kunitsõn, N.; Liiv, K.; Leppik, L. Omandireformi Sotsiaalsed ja Õiguslikud Mõjud; Tallinna Ülikool: Tallinn, Estonia, 2021; Available online: https://www.rahandusministeerium.ee/system/files_force/document_files/omandireformi_uuringu_koondaruanne.pdf?download=1 (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Kasepalu, A. Mis Peremees Jätab, selle Mets Võtab. Maakasutus Eesti Külas; Eesti Teaduste Akadeemia: Tallinn, Estonia, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Mander, Ü.; Palang, H. Changes of landscape structure in Estonia during the Soviet period. GeoJournal 1994, 33, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palang, H. Time boundaries and landscape change: Collective farms 1947−1994. Eur. Countrys. 2010, 2, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Virma, F. Maasuhted, Maakasutus ja Maakorraldus Eestis; Eesti Põllumajandusülikool, Maamõõdu Instituut, Halo: Tartu, Estonia, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Jensen, A.; Raagmaa, G. Restitution of agricultural land in Estonia: Consequences for landscape development and production. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. 2010, 64, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lux, M.; Kährik, A.; Sunega, P. Housing restitution and privatization: Both catalysts and obstacles to the formation of private rental housing in the Czech Republic and Estonia. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2012, 12, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuutma, K. Who owns our songs? Authority of heritage and resources for restitution. Ethnol. Eur. 2009, 39, 26–40. [Google Scholar]

- Valk, Ü. Ghostly possession and real estate: The dead in contemporary Estonian folklore. Folklore 2006, 43, 31–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zariņa, A. Path dependence and landscape: Initial conditions, contingency and sequences of events in Latgale, Latvia. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B 2013, 95, 355–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Online Estonian Encyclopedia. Available online: http://entsyklopeedia.ee/artikkel/eesti_rahvaarv (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Kuum, J. Teadus Eesti Põllumajanduse Arenguloos. II Osa (1918–1940). 1 Maareform; Akadeemiline Põllumajanduse Selts: Tartu, Estonia, 2003; Available online: https://agrt.emu.ee/full/2003_teadus_arenguloos.pdf (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Maandi, P. The silent articulation of private land rights in Soviet Estonia: A geographical perspective. Geoforum 2009, 40, 454–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palang, H.; Sooväli-Sepping, H. Are there counter-landscapes? On milk trestles and invisible power lines. Landsc. Res. 2012, 37, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurg, A. Werewolves on cattle street: Estonian collective farms and postmodern architecture. In Second World Postmodernisms; Kulic, V., Ed.; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2019; pp. 111–127. [Google Scholar]

- Nugin, R.; Pikner, T. Kõikudes lammutamise ja mälestise vahel: Kolhoosikeskuste arhitektuuri sotsiaalne pärand. Stud. Art Archit. 2021, 30, 9–38. [Google Scholar]

- Palang, H.; Paal, P. Places gained and lost. In Koht ja Paik II. Place and Location II; Sarapik, V., Tüür, K., Laanemets, M., Eds.; Eesti Kunstiakadeemia Toimetised: Tallinn, Estonia, 2002; pp. 93–111. [Google Scholar]

- Riigi Teataja. Eesti NSV Taluseadus. Available online: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/107062013007 (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Riigi Teataja. Land Reform Act. Available online: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/ee/Riigikogu/act/507012022006/consolide (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Estonian Land Board. Land Reform. Available online: https://www.maaamet.ee/en/objectives-activities/land-reform (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Kotka, A. (Estonian Land Board, Tallinn, Estonia). Personal communication, 23 December 2020.

- Laine, J.P. Beyond borders: Towards the ethics of unbounded inclusiveness. J. Borderl. Stud. 2021, 36, 745–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D. Moral Geographies. In Ethics in a World of Difference; Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Olwig, K.R. The landscape of ‘customary’ law versus that of ‘natural’ law. Landsc. Res. 2005, 30, 299–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pojman, L.P. Eetika: Õiget ja Väära Avastamas; Eesti Keele Sihtasutus, Tartu Ülikooli eetikakeskus: Tallinn, Estonia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Matless, D. Moral geographies. In The Dictionary of Human Geography, 5th ed.; Gregory, D., Johnston, R., Pratt, G., Watts, M., Whatmore, S., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell—A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2009; pp. 478–479. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, P. Social disorganization and moral order in the city. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1984, 9, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, T. Moral geographies. In Cultural Geography: A Critical Geography of Key Ideas; Atkinson, D., Jackson, P., Sibley, D., Washbourne, N., Eds.; I.B. Tauris: London, UK, 2005; pp. 128–134. [Google Scholar]

- Legg, S.; Brown, M. Moral regulation: Historical geography and scale. J. Hist. Geogr. 2013, 42, 134–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Proctor, J.D.; Smith, D.M. Geography and Ethics: Journeys in a Moral Terrain; Routledge: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D.M. Geography and ethics: A moral turn? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1997, 21, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Birdsall, S.S. Regard, respect, and responsibility: Sketches for a moral geography of the everyday. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1996, 86, 619–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.-F. The Good Life; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Morality and Imagination: Paradoxes of Progress; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Human Goodness; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sack, R.D. Homo Geographicus: A Framework for Action, Awareness, and Moral Concern; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Sack, R.D. The geographic problematic: Moral issues. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. 2001, 55, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sack, R.D. A Geographical Guide to the Real and the Good; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M. Landscape, law and justice—Concepts and issues. Nor. Geogr. Tidsskr. 2006, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, R.; Smith, D.M. Geographies and Moralities: International Perspectives on Development, Justice and Place; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Matless, D. Moral geographies of English landscape. Landsc. Res. 1997, 22, 141–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soja, E.W. Seeking Spatial Justice; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Opie, J. Moral Geography in High Plains History. Geogr. Rev. 1998, 88, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M. Justice in space? The restitution of property rights in Tallinn, Estonia. Cult. Geogr. 1999, 6, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugin, R.; Palang, H. Borderscapes in landscape: Identity meets ideology. Theory Psychol. 2021, 31, 780–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, A. The hegemony of the urban/rural divide: Cultural transformations and mediatized moral geographies in Sweden. Space Cult. 2013, 16, 88–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riigi Teataja. Republic of Estonia Principles of Ownership Reform Act. Available online: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/en/eli/ee/Riigikogu/act/520122018006/consolide (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Omandireform 30. Available online: https://jupiter.err.ee/1608260400/omandireform-30 (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Harley, J.B. Deconstructing the map. Cartographica 1989, 26, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Talujutud Maa ja Taeva vahel. Uustalunikega. 1993. Available online: https://arhiiv.err.ee/vaata/138191 (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Ellujäämise Kõver. Saaremaa. 1997. Available online: https://arhiiv.err.ee/vaata/ellujaamise-kover-saaremaa/same-series (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Kolkareportaaž. Noarootsi. 1995. Available online: https://arhiiv.err.ee/vaata/kolkareportaaz-noarootsi (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Männis, R. Tagasiärastaja; Eesti Raamat: Tallinn, Estonia, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Annist, A. Otsides Kogukonda Sotsialismijärgses Keskuskülas. Arenguantropoloogiline Uurimus; Tallinna Ülikooli Kirjastus: Tallinn, Estonia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Alanen, I. Agricultural policy and the struggle over the destiny of collective farms in Estonia. Sociol Rural. 1999, 39, 431–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennu, T.; Kukk, I.-G.; Ots, A. Maareform 30. Artiklid ja Meenutused; Maa-Amet: Tallinn, Estonia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Omandireform Eestis 1991–2021; Rahandusministeerium: Tallinn, Estonia, 2021. Available online: https://www.rahandusministeerium.ee/system/files_force/document_files/omandireform_eestis_1991-2021_web_.pdf?download=1 (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Palang, H.; Külvik, M.; Printsmann, A.; Storie, J.T. Revisiting futures: Integrating culture, care and time in landscapes. Landsc. Ecol. 2019, 34, 1807–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- News.err.ee. Land Board Starts Preparations for Land Tax Hike. Available online: https://news.err.ee/1208605/land-board-starts-preparations-for-land-tax-hike (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- News.err.ee. Report: Estonia Has Europe’s Lowest Property Taxes. Available online: https://news.err.ee/1608365310/report-estonia-has-europe-s-lowest-property-taxes (accessed on 30 December 2021).

- Woods, M. Rural; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Grünberg, K. ‘Nagu me ei olekski tööd teinud.’ Katkestused ja järjepidevused endiste põllumajandusjuhtide omaeluloolistes jutustustes. In Maaelu ja Elu Maal Muutuste Tuultes. Põllumajandusreform 20; Kohler, V., Ed.; Eesti Põllumajandusmuuseum: Tartu, Estonia, 2014; pp. 169–194. [Google Scholar]

- Loko, V. Current situation and perspective of Estonian agricultural policy. In Agricultural Development Problems and Possibilities in Baltic Countries in the Future. Finnish-Baltic Joint Seminar, Saku, Estonia. Research Publications 72; MTTL Agricultural Economics Research Institute: Jokioinen, Finland, 1993; pp. 7–9. [Google Scholar]

- Unwin, T. Rurality and the construction of the nation in Estonia. In Theorizing Transition: The Political Economy of Change in Central and Eastern Europe; Pickles, J., Smith, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1998; pp. 284–306. [Google Scholar]

- Ideon, A. Eeslinnastumisest Tallinna Linnastus. Hoonestusalade Laienemine Aastatel 1995–2005. Master’s Thesis, Institute of Geography, University of Tartu, Tartu, Estonia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lind, M.; Rennu, T. Paralleelmaailmad teede ja liinide rägastikus. In Maareform 30. Artiklid ja Meenutused; Rennu, T., Kukk, I.-G., Ots, A., Eds.; Maa-Amet: Tallinn, Estonia, 2021; pp. 289–302. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, E.; Palang, H.; Sooväli, H. Landscapes in change—Opposing attitudes in Saaremaa, Estonia. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 67, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palang, H.; Peil, T. Mapping future through the study of the past and present: Estonian suburbia. Futures 2010, 42, 700–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palang, H.; Printsmann, A.; Konkoly-Gyuró, É.; Urbanc, M.; Skowronek, E.; Woloszyn, W. The forgotten rural landscapes of Central and Eastern Europe. Landsc. Ecol. 2006, 21, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Natural Person | Legal Person | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 * | 2020 | 2010 * | 2020 |

| 13,504 | 7708 | 1651 | 3661 |

| Ownership | 1939 | 1940–1991 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Private | 66% | 0 | 58% |

| State | 33% | 100% | 41% |

| Municipal | 1% | 0 | 1% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Printsmann, A.; Nugin, R.; Palang, H. Intricacies of Moral Geographies of Land Restitution in Estonia. Land 2022, 11, 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11020235

Printsmann A, Nugin R, Palang H. Intricacies of Moral Geographies of Land Restitution in Estonia. Land. 2022; 11(2):235. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11020235

Chicago/Turabian StylePrintsmann, Anu, Raili Nugin, and Hannes Palang. 2022. "Intricacies of Moral Geographies of Land Restitution in Estonia" Land 11, no. 2: 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11020235

APA StylePrintsmann, A., Nugin, R., & Palang, H. (2022). Intricacies of Moral Geographies of Land Restitution in Estonia. Land, 11(2), 235. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11020235