1. Introduction

China’s rural poverty is associated with its environmental and geographical conditions and is mostly concentrated in the remote mountainous, border, and minority areas in central and western China [

1]. With much poverty alleviation effort having been undertaken since the 1980s, in-situ poverty alleviation (i.e., when people stay where they currently reside) became extremely inefficient [

2]. As the level of poverty of the not-yet-assisted rural people worsened, it was determined that only by relocating them out of their spatial poverty traps could the environmental, economic, and social conditions that produce poverty be avoided [

3]. Therefore, ex situ poverty alleviation relocation (ESPAR) became regarded as the best hope for lifting the remaining rural poor out of poverty, especially when they lived in mountainous regions, had low educational attainment, poor health, poor living conditions, or a combination of these. The ESPAR program, which was conceived in 2015, required convincing rural people (primarily farmers) to give up their homesteads and farms and move into newly-created medium- to high-density apartments.

ESPAR was the flagship project of China’s strategy for targeted poverty alleviation during the 13th Five Year Plan (2016-2020) [

4]. ESPAR had three objectives: affordable relocation; permanent settlement; and the improved economic wellbeing of relocated people [

3]. Spanning 22 of mainland China’s 34 provinces, ESPAR involved relocating around 10 million people from their original homes to various new sites that had better facilities and more convenient locations (in terms of provision of services by the state). Although primarily a poverty alleviation program, ESPAR was also a program to ensure the more productive use of land. A key dimension of the program was the national requirement that there be no net loss of agricultural land [

3,

5]. ESPAR was a complex, large-scale project because of its significant environmental, social, and economic impacts [

6]. Through the relocation of rural people and the demolition of their homesteads, the scheme led to a significant increase in available land, which could be used for agriculture or other purposes.

The total budget for ESPAR across all of China (2016 to 2020) was about CNY 946.3 billion (USD 146.3 billion) [

3]. The majority of the funding for the program came from long-term low interest loans from the Agricultural Development Bank of China, the China Development Bank, and government bonds. Despite being a national program, ESPAR was implemented at the level of municipalities, with municipal governments having to repay the loans, which they funded by selling ‘land quota’ (i.e., the right to convert farmland to construction land) to more developed municipalities who sought to offset their conversions of agricultural land to construction land [

7]. Construction land refers to land that is used for urban expansion (i.e., housing or industry).

ESPAR was primarily a voluntary program for the rural poor. Arguably, it had significant benefits for people who relocated, especially in terms of improved housing and living conditions. The scheme was undertaken by the Chinese authorities for several reasons, including poverty reduction; the preventative resettlement of people out of hazardous locations; natural resource management reasons (e.g. the reforestation of fragile lands); and to enable the consolidation of land for more efficient farming [

6]. The ESPAR policy declared that relocated householders would be offered free training programs, given employment guidance and that those who had difficulty obtaining employment would be prioritized for community jobs such as security, gardening, or maintenance work. At least one member of each relocated household was guaranteed to get a job if they were able and willing to work.

Despite its benefits, the scheme had several problems (discussed in detail below). One issue related to how the scheme was funded, which demanded that local governments be able to re-utilize the land that becomes available from the demolition of vacated homesteads. The objective of improving economic wellbeing also meant that there must be land available for industrial development (to create jobs for displaced farmers). Thus, it was essential that the land on which the old homesteads stood be available for other uses and, therefore, that the homesteads were actually demolished. However, many rural people participated in the program in order to get a new apartment but then did not vacate (and demolish) their old homesteads.

The purpose of this paper is to explore the key factors that influenced the intention and behavior of farmers in relation to homestead exit facilitated by ESPAR. By homestead exit, we mean the vacating and demolishing of homesteads and land rehabilitation (i.e., removal of all debris) so that the land could be used for other purposes. Our research will increase understanding and will provide a scientific basis for improving Chinese poverty alleviation policies and enhancing the wellbeing of resettled farmers. We make three contributions: we identify the factors that influence an individual farmer’s attitudes and behaviors towards homestead exit; we consider how an individual farmer’s attitudes and behaviors are affected by three key psychological factors and by their perception of post-relocation support; and we examine the moderating effect of the age of the farmer, and whether they will continue to farm or change to other livelihood activities once relocated.

2. A Short Note about the Categorization of Land in China

With China being a socialist country, the state owns all urban land, while rural collectives have ownership over rural land [

8]. The administration of a rural collective was generally at the village level. Each person with a rural registration (hukou) can be a member of a collective. Each collective allocates farmland and rural homestead land to its members free of charge, based on the characteristics of the household unit.

Rural land is classified into three types: agricultural land; land for residential and commercial purposes (also called construction land); and unutilized land [

9]. Construction land is further broken-up into land for commercial purposes, rural homestead land, and public land. Rural homesteads are generally associated with farms. However, strictly speaking, a rural homestead only refers to the buildings and the land on which they stand, rather than to any associated farmland. Thus, homesteads include the living quarters (i.e., houses), sheds and workshops, and any small vegetable plots, poultry coops, and barns or pens for domestic animals.

The large number of smallholders and their scattered distribution means that homestead land accounts for a significant area of land in rural areas of China [

10,

11]. The relocation of rural people and the demolition of their homesteads makes land available for other purposes. Given the restriction of no net loss of agricultural land, municipalities need to have an equivalent ‘quota’ (or right) to convert land from agriculture to other purposes. A rural municipality could use the land made available by ESPAR itself (e.g., for industrial development), or it could sell the quota (right) to a more developed municipality that needed to offset its land conversions.

3. Ex Situ Poverty Alleviation Relocation and the Link Policy

China is the most populated country in the world, with over 1.4 billion people. However, it is also a very large country, although much of its area is covered by mountains. Consequently, there is extreme population pressure on its fertile land. Historically, this population pressure pushed some people to live in mountainous regions away from services, flood-prone areas, and other precarious locations, for example, where there is a risk of landslides. Therefore, managing land and land use has been a key concern of successive governments, and land policy has played a key role in China’s economic development [

12].

The 13th Five Year Plan and related policies required that there be no net loss of farmland. Under the so-called Link Policy (which links urban land to rural land), any loss of farmland (whether in an urban or rural area) had to be offset by an equivalent increase in farmland elsewhere [

13]. Consequently, ESPAR usually moved people into high-density apartments, so that the land footprint for housing was smaller. Although the new apartments were usually built on previous agricultural land, given the aggregation of people into high-density living, the total amount of land available for agriculture or other purposes generally increased [

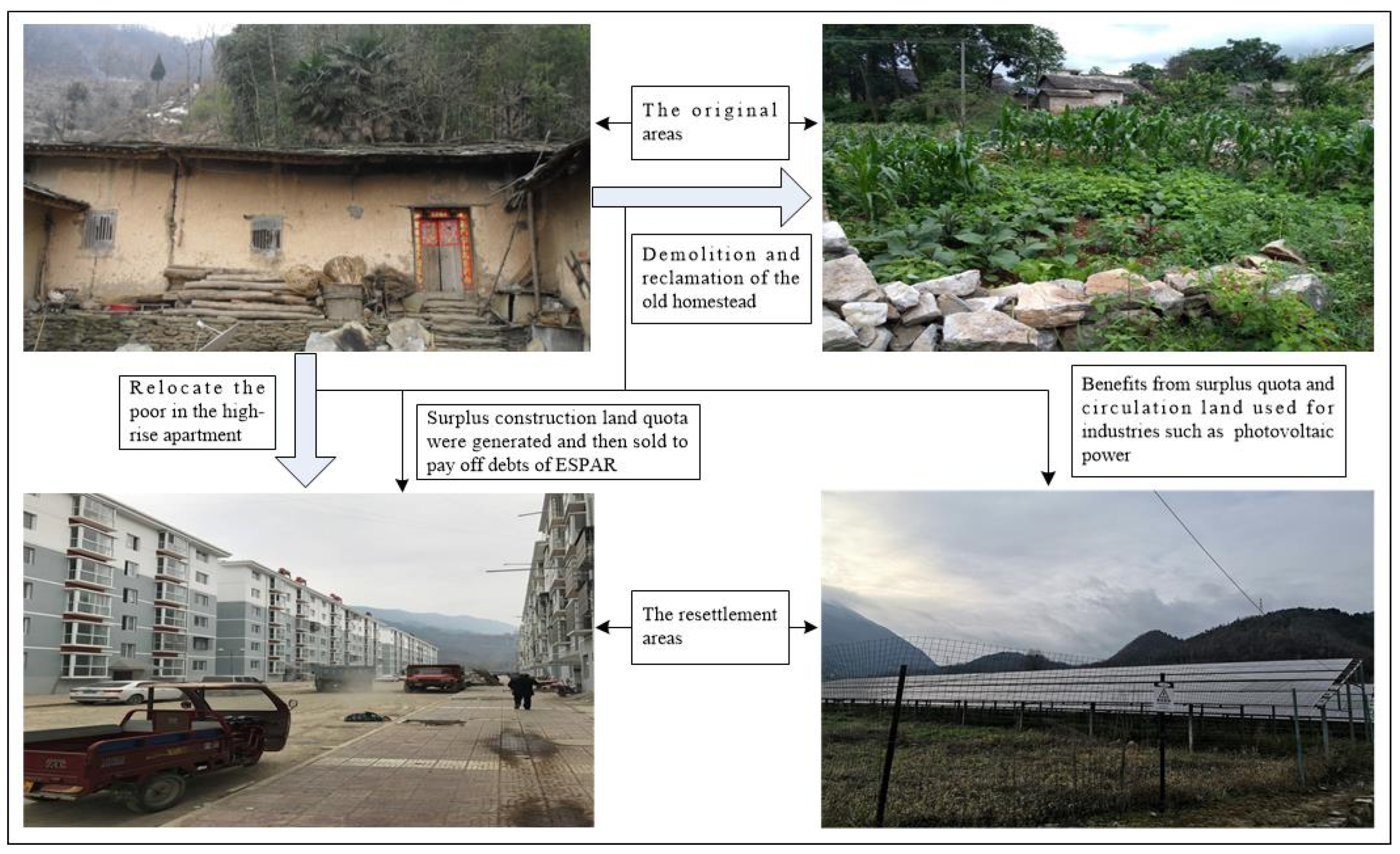

6]. In a rural municipality, the surplus land quota that was created through this aggregation process could be transferred within or across provinces. The land that was reclaimed from the demolition of old homesteads could be repurposed in two ways. If converted to agricultural land, the quota or right could be sold to other municipalities. Alternatively, it could be used to support the development of industry, with solar farms and labor-intensive production activities being typical.

Figure 1 is a schematic or infogram that shows how, through the concentration of people into high-density living, rural homestead land can be converted into land with a different land use, making land quota available for other purposes.

A fundamental problem with the ESPAR scheme, however, is that it required farmers to voluntarily participate, voluntarily move into new housing and demolish the old homesteads and rehabilitate the land (removing all debris) themselves. While rural people were keen to have new housing, as we discovered, more than half did not demolish their old homestead. The strong demand for land in China has generated significant interest in how to increase compliance with the requirement to demolish the old homesteads (and is a key aspect of this paper).

China’s complex history with imperialist, nationalist, and various communist phases has resulted in the lack of any tradition of individual ownership of land [

14]. Land ownership remains a vexed issue. Getting farmers to leave their homesteads has been difficult. However, in order for the ESPAR program to be successful, the local governments had to convince relocated people to demolish their old homesteads so that the land could be put to other uses. Although the new apartments were favorably regarded, the destruction of old homesteads caused much tension [

6,

11]. The policies related to ESPAR were complex, and farmers found it hard to understand why their homesteads had to be destroyed. Farmers often thought that homestead exit was a form of compulsory land acquisition, rather than being a voluntary program. Their resistance reduced the efficiency of the program and caused social unrest [

15].

In order to recruit volunteers, the municipal government publicized the program, and, over time, most farmers signed an application to participate and an agreement that they would exit their old homestead (i.e., demolish and rehabilitate). However, after moving into their new apartments, some people (about half) were still reluctant to relinquish their homestead and failed to do the expected demolition and rehabilitation. Some even moved back to their old homesteads. According to our interviews, there were two reasons for this. Firstly, some were not genuinely committed in the first place. Farmers often misrepresented their plans and level of commitment and only expressed views that aligned with the requirements of the scheme in order to be eligible for new housing and financial support. Secondly, after moving and establishing new livelihoods, some people thought that their ongoing income was insecure, the cost of living was higher in the new location, that their new life was difficult or unpleasant, or a combination of these; therefore, they wanted to keep their old homestead either for nostalgia, to keep their future options open, or for both reasons.

Although voluntary, the ESPAR program was a top-down, planned social change process led by the state [

16]. Given the logics at play, the various stakeholders all engaged in strategic behavior. Local governments sometimes deviated from the intended implementation of the policy [

17]. Specifically, local governments often exhibited: a lack of commitment to post-relocation support; excessive focus on the written text of the policy rather than on the quality of the poverty alleviation process; a perfunctory approach to the task; and a lack of consideration of the realities of life. As a result, most relocated farmers faced numerous adaptation and integration problems [

18]. Due to concerns about their future livelihood and wellbeing, many farmers changed their plans, decided to keep their old homesteads, or did both, even though they had signed exit agreements (including to demolish the homestead and rehabilitate the land) [

19]. Some farmers even decided to give up the new housing rather than leave the old homestead. Therefore, it is important to study the farmer decision-making process and the factors that influence their homestead exit intention and behavior.

Previous studies on ESPAR have mainly focused on the evolution of the policy, the rationale for the policy, and its implementation [

11,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Only a few studies have focused on the importance of homestead exit [

24], and there has been little focus on exit intention and behavior from the perspective of relocated farmers. Recent research has shown that the factors that influence farmers’ homestead exit include individual characteristics, income, family wealth, the level of compensation, employment opportunities, external environmental factors in the original and new locations, social security arrangements, and institutional factors [

10,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Some studies have analyzed the influence of anticipated risk and feasibility [

19,

29,

30]. However, all these studies ignored the important role of psychological factors in homestead exit.

Although several studies have discussed the theoretical basis and rationality of the program, few studies have considered homestead exit empirically. Most studies have assumed that farmers were homogeneous and have given little attention to the heterogeneity of farmer behavior, generational differentiation, or to post-relocation livelihoods. Previous studies have mainly focused on farmers’ subjective exit intention but lacked in-depth analysis of actual exit behavior. Due to the fact that exit intention before relocation often deviated from exit behavior after relocation, it is appropriate to take both intention and behavior into consideration in our research.

4. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

Two theories that have wide support and application to decision making are the theory of reasoned action [

31] and its derivative, the theory of planned behavior (TPB) [

32,

33]. Ajzen developed the TPB to contribute to understanding human behavior [

32,

34], specifically by bringing ‘perceived behavioral control’ into the theory of reasoned action [

31]. Ajzen’s theory has two aspects. Firstly, behavior is seen as a function of the willingness to perform a behavior (i.e., intention). Secondly, intention is seen as a function of three psychological factors: (a) behavioral attitude, which reflects the individual’s positive or negative appraisal of a behavioral option; (b) subjective norms, which refers to the social pressure from reference group members that one perceives they should comply with in order to enact the behavior; and (c) perceived behavior control (PBC), which refers to the degree of control one perceives they have over their behavior, that is, the ease or difficulty of performing the behavior [

35]. The more favorably a behavior is evaluated and the more social pressure a person perceives they should comply with, coupled with greater PBC, the stronger behavioral intentions will be, which, in turn, should influence behavior. The TPB has been applied across many fields, especially those that utilize psychological and sociological ideas [

35]. Using the original components of the TPB, we can hypothesize that:

Hypotheses 1 (H1). The behavioral attitude of relocated farmers towards homestead exit will be positively correlated with their exit intention.

Hypotheses 2 (H2). The subjective norms of relocated farmers will be positively correlated with their homestead exit intention (e.g., if farmers perceive that people who are important to them have favorable views about exit, so will they).

Hypotheses 3 (H3). Perceived behavior control will be positively correlated with the homestead exit intention of the relocated farmers.

Despite many studies suggesting that the TPB is useful for predicting individual intention and behavior, TPB papers have generally suggested that further variance could be explained by the inclusion of additional variables [

36]. Research has shown that only some of the potentially explainable variance of behavioral intention is explained by Ajzen’s three psychological factors [

37,

38,

39,

40]. Ajzen also indicated that, to increase explanatory power, his model should be modified to adapt to different situations [

33].

Recent studies have expanded on the TPB in two main ways. One was by adding other variables that potentially affect intention or behavior. Another way relates to the internal relationships between the three psychological factors. The consideration of other variables and internal relationships is generally called the ‘extended theory of planned behavior’ [

40,

41,

42].

The starting point for our research was the observed deviation between farmers’ signed commitment to demolish and rehabilitate their homesteads and their ultimate behavior regarding homestead exit. Whether a farmer exited or not depended not only on their intention at the beginning of the relocation process, but also on the adequacy of post-relocation support. In the ESPAR process, farmers must voluntarily apply to relocate, sign an application form, and sign an agreement to exit the old homestead (i.e., to demolish and rehabilitate). Farmers would often indicate that they accepted the various requirements and arrangements and would sign an exit agreement to demolish and rehabilitate their old homestead. However, at the time of signing, many still had many concerns about whether they would be able to adapt to and live with the conditions, uncertainties, and risks that came with moving into their new accommodation. As a result, although they had signed an exit agreement, a considerable number of farmers took a ‘testing the water’ approach. Whether they would actually exit the homestead after relocation depended on the level of livelihood improvement and social integration they experienced. Thus, their initial expressed exit intention does not fully explain or predict their final exit behavior.

According to gradual adaptation theory [

43], the decision of whether to exit the homestead or not will be adjusted according to what happens after relocation. Once the relocated farmers have settled into their new apartments, have received post-relocation support (e.g., employment, skills training, financial support, and access to public services), and have been compensated for any lost assets, they may operationalize their exit intention into actual behavior, ideally demolishing the homestead and rehabilitating the land.

In theory, there are two ways by which the support policies promote homestead exit. Firstly, effective support strengthens the exit intention. Secondly, the support policies directly promote exit behavior by providing a bonus payment for a full exit and by providing employment opportunities to facilitate life in the new location. Based on this reasoning, the following two hypotheses can be proposed:

Hypotheses 4 (H4). The extent to which a farmer positively perceives the post-relocation support will be positively correlated with their homestead exit intention.

Hypotheses 5 (H5). The extent to which a farmer positively perceives post-relocation support will be positively correlated with their homestead exit behavior.

In the classic TPB, behavioral attitudes, subjective norms, and PBC exist as independent exogenous variables, meaning that they are regarded as not being inter-related [

33], and only a few studies have focused on the interactions between them [

44]. However, in some variations of the extended TPB, several scholars have come to conclusions that are different to the classic models. One study showed that when people form a behavioral attitude, they then take into account how others expect them to act, and they also consider their personal willingness to comply with this expectation [

45]. Pressure from people who are important to them and the influence of the demonstration effect (i.e., learning from watching others) also affect people’s perceived degree of ease or difficulty in completing a certain action. Therefore, subjective norms affect behavioral attitudes and PBC [

41,

44,

46].

In China, people live in a close-knit society; therefore, the views of people who are important to them will affect their behavioral attitude towards homestead exit and towards the resources and assistance they would expect. Thus, two hypotheses can be proposed:

Hypotheses 6 (H6). When subjective norms about exiting the old homestead are more positive, relocated householders’ behavioral attitude towards exiting will be more favorable.

Hypotheses 7 (H7). When subjective norms about exiting the old homestead are more positive, relocated householders’ perceived behavior control about exiting will be higher.

Finally, according to the classic TPB, behavior is a function of the willingness to perform a behavior [

31]. When predicting behavior, a key factor is people’s intention to participate or not participate in the behavior. Thus, it can be hypothesized that:

Hypotheses 8 (H8). Relocated householder exit intention will be positively correlated with their exit behavior.

5. Methodology

This paper uses the extended theory of planned behavior and brings exit intention and exit behavior into a unified research framework to explore the influence of psychological factors and support policies on farmers’ homestead exit intention and behavior. The analysis is based around the theoretical model depicted in

Figure 2. This framework was tested by using structural equation modelling using data relating to 830 farmers that was extracted from a large survey implemented in Southern Shaanxi Province, China, in December 2017 and January 2018. All hypotheses could be tested with the one model.

5.1. Design of Scales

Exit intention was measured by two variables; one was the intention to demolish the homestead and the other was the intention to rehabilitate the homestead land so that it can be used for farming. These two variables were measured on a 5-point scale. Exit behavior was measured by asking questions about whether demolition and rehabilitation had actually happened and were recorded using a yes or no dichotomy.

Measures for behavioral attitude, subjective norms, PBC, and perception of post-relocation support were adapted from established scales. Measures for behavioral attitude (4 items) and PBC (4 items) were taken from Ajzen [

33], Tonglet et al. [

47], and Tan et al. [

40]. The four components of behavioral attitude were: survival rationality; economic rationality; development rationality; and ecological rationality. PBC was broken down into ‘internal self-efficacy’, which referred to the farmer’s ability and confidence to perform a behavior and ‘external controls’, which in our context referred to the quality of the support provided to facilitate relocation and for the farmer to become established in the new location [

48,

49]. Subjective norms (4 items) refer to the descriptive indicators that characterize people’s perceptions about what other people do (i.e., the norms of is) and to injunctive norms, which characterize the perception of what other people approve or disapprove of (i.e., the norms of ought) [

50,

51]. A 5-point response scale was used to measure each item. The full list of items is given in our results.

We conducted several pre-tests to fine-tune the scales according to feedback from farmers and our colleagues. The final scale contained 21 items. Except for exit behavior, in which 1 was yes and 0 was no and a measure of wealth (current bank account balance grouped into 5 groups), the other 18 items utilized a five-point response scale: 1 strongly disagree; 2 disagree; 3 neither agree nor disagree; 4 somewhat agree; and 5 strongly agree.

5.2. Description of the Study Area and the Dataset

Shaanxi Province is regarded as being in the north-west of China (see

Figure 3). Its capital is the ancient city of Xi’an. Southern Shaanxi is a mountainous region where natural disasters, land degradation, and poverty have coexisted for centuries. Southern Shaanxi is typical of much of Western China, including of most places where the ESPAR program has been implemented. In fact, the ESPAR program first started in Shaanxi. In 2011, Shaanxi Province initiated a disaster risk reduction project that aimed to move 2.4 million people out of disaster-prone locations. The success of this early experience in Shaanxi ultimately led to ESPAR becoming central to China’s poverty alleviation practice and was a key part of the 13th Five Year Plan. Between 2011 to 2015 (i.e., prior to the official ESPAR program), 1.12 million people were relocated in Shaanxi, and a further 1.26 million were relocated between 2016 and 2020 as part of the ESPAR program. The data for this paper relates to people moved under the original program initiated in Shaanxi Province and the ESPAR program. As part of a bigger project looking at the experience of rural poverty, this paper uses the data relating to 830 households that were resettled between 2011 and 2016.

5.3. Data Collection and Analysis

In December 2017 and January 2018, a face-to-face household survey was conducted in the Hanzhong, Ankang, and Shangluo municipalities of the Southern Shaanxi Province. The study sites included: Baihe County, Hanbin District; Hanyin County of Ankang; Liuba County; Xixiang County; Lueyang County of Hanzhong; Danfeng County; and Zhen’an County of Shangluo (see

Figure 3). A total of 62 villages and resettlement communities were included. The survey was supplemented with around 60 unstructured interviews or conversations with local government officials and local leaders. The main purpose of these unstructured interviews was to understand the operational practicalities of homestead exit in each particular location.

The households to be interviewed were identified by randomly selecting two to five locations in each county and between 30 and 60 households from each village or community using stratified sampling to ensure the representativeness of the sample. The individual survey respondent was usually the household head or their spouse, and all respondents were aged between 18 and 70. Apart from the scales discussed above, the survey also included household information such as land use, livelihoods, income and expenditure, and details about the old and new dwellings. A total of 1712 valid questionnaires were obtained. However, this paper focuses only on the homestead exit intention and behavior of farmers who had relocated under the auspices of the pre-ESPAR and ESPAR relocation programs. Therefore, the sample size for empirical analysis in this paper was 830 relocated households coming from the eight counties indicated above.

Each survey interview took around 120 min to complete. They were mostly done in the farmers’ new home. The questionnaires were completed by the interviewer. A team of about 15 interviewers associated with Northwest Agricultural and Forestry University were employed to undertake the interviewing. Participation was voluntary, and the principles of informed consent and ethical research were observed [

52]. Data was entered into an Excel spreadsheet. Analysis was done using SPSS and AMOS.

6. Preliminary Description of the Sample Data

The average age of the 830 relocated householders was 50.0 years (See

Table 1). About 15% had not been to school at all, three-quarters (75%) had finished primary school or junior high school (i.e., up to 9 years of schooling), and only 9.5% had attended senior high school or above. Some 82.5% of the original residences were located in deep valleys or on steep hillsides. Before relocation, 79% of respondents lived in houses primarily made of earth and wood. Some 16% of relocated households had an annual per capita disposable income of less than CNY 5000 (USD 770) in 2017. Before relocation, all farmers had signed an exit agreement, but when they settled down in their new home, only 63% expressed a willingness to exit their old homestead. At the time of the research, 47% of the relocated farmers had demolished the homestead and 22% had rehabilitated the homestead land. There is clearly an inconsistency between exit willingness and exit behavior.

With regard to awareness of the exit policy, interviewees were asked two questions: “how well did you know about the homestead exit policy”; and “how well did you understand that you were required to exit the homestead within a specified period after relocation”. For the first question, 31% of the respondents reported they knew “nothing”, 31% said that they “did not know much”, 27% said that they “generally knew”, while only 9% and 1% said they “knew” or “knew well”. Overall, relocated householders’ knowledge of the exit policy was poor. For the second question, 22% of the respondents did not know that they had to exit their homestead at all, 35% reported they “did not really know”, 25% “generally knew”, and only 17% and 1.4% “knew” or “knew well”. Generally speaking, although the farmers had signed an application form and an agreement to exit form (stating that they would demolish and rehabilitate their old homesteads), some interviewees said that they signed the forms just to obtain the relocation support but had little knowledge about the specific details of what was expected of them. It is possible that local governments were keen to achieve large take-up rates and therefore understated the obligations expected of people who participated.

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for the variables to be used in the structural equation modelling. Of particular note is that there is generally a low level of satisfaction with the relocation process. None of the variables had abnormal distributions.

7. Results of the Structural Equation Modelling

Earlier in the paper,

Figure 2 presented the conceptual model of exit intention and exit behavior that was the basis of the analysis in this paper. This model was tested using the data from 830 relocated farmers. The AMOS statistical package was used for the structural equation modelling. Before we discuss the results of our hypothesis testing, we first provide evidence of the robustness of the model (reliability, validity, and overall model fit).

7.1. Reliability and Validity of Scale

Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) are measures of reliability. Generally, for a scale to be considered acceptable, Cronbach’s alpha should not be lower than 0.7. CR is calculated by using the standardized factor loadings of the observable variables. If the CR of the latent variables exceeds 0.6, it means there is adequate reliability [

53].

Table 3 indicates that the factor loadings for each observable variable ranged from 0.513 to 0.950. Except for exit intention, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the scales were all greater than 0.7, and the CR was between 0.827and 0.964, indicating that the scales had adequate internal reliability.

Validity includes content validity and construct validity. Content validity refers to the degree to which the scale covers the content it is supposed to measure. The scales for this study were based on the underlying theory (i.e., extended TPB), the literature, relevant suggestions from experts, and field observations. Because of this diversity of sources, the scales are likely to accurately reflect the views of the relocated people’s exit intention and exit behavior at theoretical and practical levels. Construct validity incorporates both convergent validity and discriminant validity. Convergent validity indicates how well the observable variables measure the corresponding latent variables, while discriminant validity represents the extent to which one latent variable is truly distinct from another [

54]. Average variance extracted (AVE) was used in this study to measure convergence validity, and the square root of AVE and squared correlations between the latent constructs were used to measure the discriminant validity [

54,

55]. In

Table 4, the AVE of each latent variable was greater than the cut-off value of 0.5, ranging from 0.536 to 0.872, indicating that convergence validity was adequate. In

Table 4, the square root of AVE on the main diagonal was greater than the squared correlations, indicating that the latent variable had significant discriminant validity. To sum up, the scales had high reliability and validity allowing further analysis.

7.2. Overall Model Fit Test

It is typical to start the interpretation of results of model testing by checking to see if there are any anomalies in the output [

56]. The most common anomalies include negative error variances, correlations greater than 1, the covariance matrix not being positive definite, standardized coefficients exceeding or being very close to 1, and standard errors being extremely large or small. Only if there are no anomalies, should further interpretation be carried out. In our results, the most appropriate modified model was developed according to the modified index from the AMOS output and from our theoretical base. The goodness-of-fit for the model was examined to decide whether the discrepancy between the implied and observed variance-covariance matrices was trivial or not. In the optimal modified model we selected, all standardized coefficients were less than 0.95, the variances of measurement error were between 0.063 and 0.753, the correlation coefficients of standardized estimates of covariances were between 0.021 and 0.950, and the covariance matrix and the correlation matrix were positive-definite. As no anomalies were noted, the model did not violate preliminary evaluation criteria, and a global goodness-of-fit test could be carried out.

Table 5 shows the goodness-of-fit results for the proposed SEM model and the suggested cut-off value for each fit index. It can be seen that, except for χ2, NFI, RFI, most of the results for the goodness-of-fit indices meet the recommended criteria, indicating that the theoretical model proposed in our study fits with the set of observations, and, therefore, that the results of our study are robust.

7.3. Hypothesis Testing

As the observable variables were in accordance with multivariate normality, the maximum likelihood algorithm was used to estimate the SEM. Our analysis (see

Table 6) indicated that all the hypotheses were significant at the 0.01 level. The results were consistent with our theoretical expectations.

Attitudes towards homestead exit (β = 0.201, t = 4.886,

p < 0.01), subjective norms (β = 0.300, t = 6.959,

p < 0.01), and perceived behavior control (β = 0.258, t = 6.762,

p < 0.01) were significantly positive influences on relocated farmers’ homestead exit intentions, thus confirming H1, H2, and H3. The standardized path coefficients of attitudes towards exit intention was significantly positive, which indicates that the more favorable the awareness and evaluation of the farmers’ homestead exit, the more willing they were to exit their old homestead. As was shown in

Table 3, the factor loading of farmers’ economic rationality and development rationality are all above 0.870, which is greater than the 0.602 scored for survival rationality and the 0.513 scored for ecological rationality. Therefore, only by ensuring secure income and solving long-term development problems, such as education and medical care so that descendants will benefit into the future, will farmers adopt positive attitudes towards exiting their old homestead. Furthermore, the standardized path coefficient of farmers’ subjective norms on their exit intention was significantly positive, indicating that the greater the pressure from people important to them, the higher their exit intention.

As was shown in

Table 3, the factor loadings of the other relocated farmers’ demonstration effect (SN1) was 0.941, the village leaders’ supervision (SN4) was 0.919, homestead exit-agreements (SN3) was 0.950, and other relocated farmers’ attitudes (SN2) was 0.919. Other studies have shown that, only when the number of farmers who exit reached a certain number, will others be encouraged to follow [

50]. Therefore, it is particularly necessary to pay attention to the demonstration role of the earlier-relocated households. The standardized path coefficient of farmers’ PBC on their exit intention was significantly positive, which indicated that the stronger the self-efficacy and the more resources they thought they would get, the more willing they were to exit their homestead. As shown in

Table 3, the factor loadings of perception of government support, perception of compensation, and the farmers’ bank account balance were 0.895, 0.866, and 0.811, respectively, which were greater than that of farmers’ risk attitude (0.591), indicating that most relocated farmers did not consider homestead exit to be a risky event.

Post-relocation support policies had a significantly positive influence on exit intention (β = 0.499, t = 13.773,

p < 0.01) and exit behavior (β = 0.830, t =19.198,

p < 0.01), thus confirming H4 and H5. As a result, the more comprehensive the support policies, the stronger the relocated farmers’ exit intention and the more likely they were to actually exit their homestead. According to

Table 3, training exhibited the highest factor loading (0.767), and the factor loadings for financial access, social integration, infrastructure and public services, job availability, and business conditions were 0.739, 0.734, 0.728, and 0.691, respectively. In our study, only 19.6% of farmers had participated in the skill training organized by the local government or by various enterprises, this had been done an average of 3.6 times. This helps farmers find jobs in local factories. A decent economic foundation and the employment creation effect brought about by the population aggregation in the new community ensured that at least one member of each relocated family was employed. In Southern Shaanxi, along with the construction of new housing, a large number of services such as education, sanitation, culture and sports, commercial enterprises, and shopping have been built. Furthermore, support facilities and infrastructure such as roads, basic telecommunications, and garbage and sewage treatment facilities are greatly superior to what was available in their original locations. Furthermore, low-interest or interest-free loans for the relocated farmers have been provided to help them start their own businesses. There were also various social and cultural activities encouraging relocated farmers to integrate into the new environment.

Subjective norms were significantly positive influences on behavioral attitude (β = 0.589, t = 12.259,

p < 0.01) and PBC (β = 0.526, t = 15.612,

p < 0.01), thus confirming H6 and H7. The results indicated that the demonstration effect, pressure from people who are important to the farmers, and the extent of farmers’ understanding of the exit agreement all played an important role in the formation of the attitudes of the relocated farmers. When people who are important to the farmers identified with or advocated homestead exit, the relocated farmers would be more approving of homestead exit. Furthermore, when the social norms were more positive, farmers would be more confident to exit their homestead. Similar results have been found in other studies [

41,

44]. The social norms influenced farmers’ perceptions in relation to the external impediments to exiting their homestead. The standardized path coefficient of the exit intention on exit behavior was significant at the 1% level (t = 5.096,

p < 0.01), and H8 is verified, but the coefficient is small, only 0.162, indicating that the explanatory power of farmers’ exit intention on the final exit behavior was relatively low. This was consistent with what was predicted.

In order to illustrate the influence of post- relocation support policies and psychological factors on exit intention and exit behavior, the direct, indirect, and total effects were estimated. The results are shown in

Table 7. In terms of total effect, the subjective norms and support policies had the highest effect on exit intention and exit behavior, reaching 0.554 and 0.911, respectively. In terms of direct effect, the support policies were the most important factor that directly affected exit intention (0.499) and exit behavior (0.830). In terms of indirect effect, behavioral attitude and PBC mediated the effect between subjective norms and exit intention, with the indirect effect reaching 0.254. However, the indirect effects of support policies and psychological factors on exit behavior through exit intention were relatively small and were less than 0.100.

7.4. Analysis of Multi-Group SEM

Individual attributes may impact on farmers’ attitudes, subjective norms, and PBC [

57]; therefore, the influence of the psychological factors on exit intention and behavior will be heterogeneous. However, the mode of resettlement may influence farmer’s homestead exit behavior. That is, different relocation modes (i.e., whether farmers can continue to farm or not) may account for different evaluations of homestead exit. Therefore, in the SEM, the farmers’ attributes and relocation mode were set as the moderating variables, and the multi-group SEM was used to evaluate whether the theoretical model (extended TPB) we proposed was applicable to different sample groups. According to recent studies [

19,

20], the age of the household head was selected as the individual attribute to carry out the grouping analysis. Specifically, the sample families were divided into a low-age group (head age under 50 years old) and a high-age group (head age over 50 years old), as well as into an agricultural relocation group and an urbanized relocation group. The urbanized relocation mode was characterized by enjoyment of complete infrastructure and public services, increase in non-agricultural employment opportunities, promotion of industrial agglomeration, and population concentration. The agricultural relocation mode was mainly characterized by relatively minor changes in the livelihood and lifestyle of the households [

2]. Goodness-of-fit of the six candidate models, which include the default model, equal measurement weights model, equal structural weights model, equal structural covariance model, equal variance of structural residuals model, and equal variance of measurement residuals model, were examined. The results show that all six models were convergent, recognizable, and fit. According to the AIC and ECVI standards for selecting the most suitable and simplified model and the results of the nested model comparison, the default model was chosen for the multi-group analysis. The normed chi-squares (NC) of the two multi-group models were 1.124 and 1.225, respectively, both smaller than the cut-off value of 2, indicating a good model. The comparative fitness index (CFI) coefficients were 0.987 and 0.975, respectively, both greater than 0.9. The parsimony-adjusted normed fit index (PNFI) values were 0.742 and 0.733 respectively, both greater than 0.5. The root mean square errors of approximation (RMSEA) were 0.022 and 0.030, respectively, both smaller than 0.05. All of the above were indicative of a good fit between the hypothesized multi-group SEM and the sample data. The specific estimation results are given in

Table 8.

As revealed in

Table 8, the test results for the hypotheses were consistent with the whole sample and conformed to theoretical expectations; this was only not true for H1, which was not significant for the high-age group and the agricultural relocation group. This indicates that our theoretical model was sound and reinforced by the results. Critical ratios (C.R.) were calculated to test whether the differences between parameters for the two corresponding groups were significant or not. The results showed that the differences in standardized regression coefficients for H1, H2, and H5 between the different groups were significantly not equal to 0, indicating that household age and relocation mode have moderating effects on the relationships between psychological factors and exit intention and on the relationships between support policies and homestead exit behavior.

In the household age grouping analysis, the difference in the path coefficients in BA→EI was statistically significant (C.R. = −2.894, p < 0.01). For the low-age group, β = 0.451, p < 0.01, whereas for the high-age group, β = 0.026, p > 0.1, suggesting that the behavioral attitude of the low-age group had greater impact on exit intention than for the high-age group for whom H1 was not supported. In our survey, older farmers felt more attached to their original land and preferred to stay in their hometown. Furthermore, they thought that the place where they were born and raised needed to be kept for nostalgia and for the sake of family reunions during festivals and holidays. They thought that the land surrounding their old houses could be used to plant fruit and vegetables for self-sufficiency, all of which reduced their homestead exit intention. Furthermore, as they aged, the older farmers became increasingly unable to engage in off-farm work, and as their children had grown up (and therefore did not need access to schools), their opinion of the value of exiting the old homestead was lower than the low-age group. In contrast, younger farmers showed a generally stronger awareness of the benefits and interest in exiting the homestead. For them, exiting meant a breaking away from a traditional farming lifestyle and encouraged them to find non-farm employment opportunities quickly. Exiting also provided better education opportunities for their school-age children. Overall, behavioral attitude has a stronger positive effect on homestead exit intention for younger farmers.

The path coefficients in SN→EI had a statistically significant difference (C.R. = 3.086, p < 0.01). For the low-age group, the coefficient was β = 0.245, p < 0.05, whereas for the high-age group, it was β = 0.660, p < 0.01, suggesting that subjective norms had greater impact on the exit intention of the high-age group than for the low-age group. This may be due to the fact that the high-age households tend to have traditional farming as their main source of income, they still live within a village (meaning that they tend not to travel very far), and their social contacts are mainly with other local farmers. When making exit decisions, the high-age group farmers tended to pay more attention to the previously relocated households. Due to a lack of experience and information, they also had more trust in the ESPAR program publicity and in the views of local officials and village leaders. When experiencing social pressure or demonstration effect from people who were important to them, the high-age group were more likely to have an intention to exit. In contrast, the low-age group were more knowledgeable, and they usually had their own opinions in making decisions.

In the relocation mode grouping analysis, the critical ratio showed that the path coefficients in BA→EI had a statistically significant difference (C.R. = 2.639, p < 0.01). For the urbanized relocation, β = 0.420, p < 0.1, whereas for the agricultural relocation, β = 0.091, p > 0.1. The behavioral attitude of the urbanized relocation households had a greater impact on exit intention than that of the agricultural relocation households, for whom H1 was not supported. This was likely because, under agricultural relocation, poor farmers were usually relocated within the same village or to the central village in their district, ‘moving from mountain to mountain’ or ‘moving from countryside to countryside’. Their migration distance was relatively short. Most relocated farmers in this mode were still engaged in traditional farming, and their livelihood activities and living environment had not changed greatly. Their old housing could also still be used and some of the relocated farmers lived in both places at the same time. As a result, in the agricultural relocation mode, attitudes towards exiting the homestead were less favorable. In contrast, urbanized relocation was a type of long-distance resettlement, which mainly relocated farmers to a city, county or major town where there were more opportunities. Farmers enjoyed the comprehensive public services and no longer needed to be engaged in agricultural activities. So, the economic and security functions of the old homestead were weakened, farmers’ worries about exiting were reduced, and they integrated well into the urban lifestyle. Therefore, in urbanized relocation, farmers’ behavioral attitude had a significant positive effect on exit intention.

The critical ratio also showed that the path coefficients in SP→EB had a statistically significant difference (C.R. = -1.685, p < 0.1). For the urbanized relocation, β = 0.881, p < 0.01, whereas for the agricultural relocation, β = 0.575, p < 0.01. This suggested that follow-up support policies under the urbanized relocation had a greater impact on exit behavior than for agricultural relocation. The possible reason for this was that there was a large number of enterprises, factories, shopping malls etc. near the new community, training was provided, and the relocated farmers could quickly take up employment nearby. The good infrastructure and public services in the urban area enabled the relocated farmers to enjoy better transportation, medical care and education. By switching from rural social support services to the urban social security system meant the relocated farmers would have no worries about their future life in the urban community; therefore, they were more active in exiting their rural homestead.

8. Conclusions

China’s ex situ poverty alleviation relocation (ESPAR) program has led to the relocation of millions of people from situations of poverty and precariousness to new residential situations where social services and jobs can be provided. The program was intended to improve natural resource management and social development outcomes. Arguably, it has achieved these goals to some extent. However, with the program requiring the voluntary participation of people to be relocated, including that they themselves had to demolish their old houses (homesteads) and clear (rehabilitate) the land of all building debris, there has been much non-compliance. Although all relocated farmers had signed agreements stating that they would demolish their homesteads and rehabilitate the land, after receiving their new apartments, many farmers (about half) have not followed through on their commitment to exit. Although the responses given for pre-relocation exit intention varied, from our data of 830 farmers, it is clear that there was an inconsistency between pre-relocation intention and post-relocation behavior.

Our research considered the key factors that influenced the intention and behavior of farmers in relation to homestead exit. We did this by using the extended theory of planned behavior, structural equation modelling, and by considering eight hypotheses. Our overall model was strongly supported, the reliability and validity of the latent variables (scales) was very adequate, and all eight hypotheses were confirmed. The behavioral attitude of relocated farmers towards homestead exit was positively correlated with their exit intention (H1). The subjective norms of relocated farmers were positively correlated with their homestead exit intention (H2). Perceived behavior control was positively correlated with the homestead exit intention of the relocated farmers (H3). The extent to which farmers positively perceived the post-relocation support policies was positively correlated with their homestead exit intention (H4) and behavior (H5). As subjective norms about exiting the old homestead became more positive, a relocated householder’s behavioral attitude towards exiting became more favorable (H6), and their perceived behavior control about exiting increased (H7). Relocated householder’s exit intention was positively correlated with their exit behavior (H8).

Other meaningful findings included the following. Firstly, although almost all relocated farmers had signed agreements, there were still many farmers taking a wait-and-see attitude regarding homestead exit. Secondly, farmers’ perception of the appropriateness of the follow-up support policies was highly related to homestead exit intention and behavior. Thirdly, behavioral attitude, subjective norms, and PBC directly affected farmers’ exit intention. Fourthly, subjective norms, PBC, and behavioral attitude had only small indirect effects on exit behavior. Finally, the influence of exit intention on exit behavior was statistically significant but small. Most important in ensuring exit intention and behavior was effective post-relocation support.

Our results have some general implications. Firstly, it is necessary to improve the quality of participation of farmers in the relocation planning process so that their livelihoods, interests, and abilities can be taken into account. With greater engagement, the motivation of farmers to participate in the scheme and comply with the demolition and rehabilitation expectations would be enhanced, and homestead exit would be implemented more smoothly. Secondly, in order to improve farmer awareness, self-confidence, and PBC, local government officials and village leaders should improve the planning process, the way the scheme is publicized, and the explanation of compensation arrangements and requirements for participation in the scheme. Thirdly, the experiences of farmers who have already participated in the scheme should be shared to provide greater understanding to people intending to participate. Fourthly, implementation of the post-relocation support needs to be improved, especially in relation to the provision of essential infrastructure, public services, training, and employment opportunities. Finally, there should be care to ensure that the follow-up support for relocated households is provided according to the varying characteristics of each household and people’s future livelihood activities.

There are some potential limitations to our study. Firstly, the data we use in our study are cross-sectional, making our study mainly a static analysis of the proposed relationships. Second, our model and findings apply to only certain contexts (especially the Southern Shaanxi province). It may not hold in other contexts and its generalizability is open to question because different regions have different social and economic conditions, and the mode of ESPAR in a region may have its own characteristics. Thirdly, except for the psychological factors and perception of post-relocation support we have paid attention to, there may be other social, economic, and demographic variables that might influence relocated famers’ intention and behavior in terms of leaving their old homestead. Future studies might use a more representative sample (e.g., collecting data from other regions and using longitudinal data) and a more comprehensive and extensive framework (e.g., incorporating variables such as Household Registration Reform, integrated urban–rural development into the model) to conduct further in-depth analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.S., F.V. and J.Y.; Data curation, P.S.; Formal analysis, P.S. and F.V.; Funding acquisition, P.S. and J.Y.; Investigation, P.S. and J.Y.; Methodology, P.S. and F.V.; Project administration, J.Y.; Resources, J.Y.; Software, P.S.; Supervision, F.V. and J.Y.; Validation, F.V. and J.Y.; Visualization, P.S. and F.V.; Writing—original draft, P.S., F.V. and J.Y.; Writing—review & editing, P.S. and F.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No.71573208; No.71373208; No.71874139), the National Key R&D Program “Intergovernmental International Science and Technology Innovation Cooperation” Key Project (Grant No. 2017YFE0181100), project supported by the Scholarship Council of China (Grant No. 201906300041).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the procedures in place at Northwest Agriculture & Forestry University, China, at the time the research was done.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data, models, and code used for the research reported in this paper are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y. Spatio-temporal patterns of rural poverty in China and targeted poverty alleviation strategies. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 52, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; de Sherbinin, A.; Liu, Y. China’s poverty alleviation resettlement: Progress, problems and solutions. Habitat Int. 2020, 98, 102135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Development and Reform Commission of China. The 13th Five Year Plan for the ex situ poverty alleviation relocation. 2016. Available online: https://www.ndrc.gov.cn/xxgk/zcfb/ghwb/201610/W020190905497854907205.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2016). (In Chinese)

- Research Group of Wuhan University on Follow-up Support for Relocation for Poverty Alleviation. The basic characteristics of relocation for poverty alleviation and path selections of the follow-up support. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2020, 12, 88–102. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Lin, G.C. New geography of land commodification in Chinese cities: Uneven landscape of urban land development under market reforms and globalization. Appl. Geogr. 2014, 51, 118–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, W.; Li, Y. Targeted poverty alleviation and land policy innovation: Some practice and policy implications from China. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; de Vries, W.T.; Zhao, Q. Understanding rural resettlement paths under the increasing versus decreasing balance land use policy in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 103, 105325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Brown, G.; Liu, Y.; Searle, G. An evaluation of contemporary China’s land use policy–The Link Policy: A case study from Ezhou, Hubei Province. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y. Rural land system reforms in China: History, issues, measures and prospects. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D. The research of rural residential land return mechanism in household registry reform. J. S. China Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2014, 13, 46–52. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, S.; Li, J.; Lo, K.; Guo, H.; Li, C. China’s rapidly evolving practice of poverty resettlement: Moving millions to eliminate poverty. Dev. Policy Rev. 2019, 38, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Besley, T.; Burgess, R. Land Reform, Poverty Reduction, and Growth: Evidence from India. Q. J. Econ. 2000, 115, 389–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Zhang, Z. Does China’s ‘increasing versus decreasing balance’ land-restructuring policy restructure rural life? Evidence from Dongfan Village, Shaanxi Province. Land Use Policy 2017, 68, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Vanclay, F.; Yu, J. Evaluating Chinese policy on post-resettlement support for dam-induced displacement and resettlement. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2021, 39(5), 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Liu, Y.; Brown, G.; Searle, G. Factors affecting farmers’ satisfaction with contemporary China’s land allocation policy–The Link Policy: Based on the empirical research of Ezhou. Habitat Int. 2018, 75, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. Planned social change, pressure of policy implementation and risk of poverty alleviation: Analysis on the policy of relocation of poverty alleviation. J. Yunnan Adm. Coll. 2017, 3, 20–25. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xing, C. Poverty alleviation guarantee under pressurized system and government failure in governance of poverty. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2016, 16, 65–73. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Long, Y.; Liu, X. Interpretation of the poverty alleviation relocation policy from the perspective of livelihood space. Seeker 2019, 1, 114–121. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Cai, J. The influences of perceived values and capability approach on farmers’ willingness to exit rural residential land and its intergenerational difference. China Land Sci. 2016, 30, 64–72. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lo, K.; Xue, L.; Wang, M. Spatial restructuring through poverty alleviation resettlement in rural China. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 496–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Yin, H.; Wang, S.; Wang, Q. Does poverty alleviation relocation reduce poverty vulnerability. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2018, 28, 20–28. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Zheng, H.; Li, S.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Zeng, W.; Liang, Y.; Polasky, S.; Feldman, M.W.; Ruckelshaus, M.; et al. Impacts of conservation and human development policy across stakeholders and scales. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 7396–7401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, W.; Xu, J.; Li, J.; Li, S. Rural Households’ Poverty and Relocation and Settlement: Evidence from Western China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2019, 16, 2609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Geng, J.; Wang, J. Research on the collaborative promotion mechanism of relocation poverty alleviation and paid homestead exit. Soc. Sci. Yunnan 2018, 2, 109–116. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, B.; Zang, B. An analysis of farmers’ willingness to withdraw from land and its influencing factors in the reform of household registration system. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2011, 11, 49–61. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, R. A study on the farmers’ response to the withdrawal of rural homestead: Based on the analysis of 486 sample farmers in 12 villages of Chengdu City, Sichuan Province. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2014, 4, 43–51. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Chen, L.; Long, K. Rural homestead property rights system study: Based on analysis perspective of the relationship between incomplete property rights and subject behavior. J. Public Manag. 2014, 11, 39–54. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, A.; Deng, S. Expected return, risk expectation and residential land quitting behavior among farmers in Songjiang and Jinshan Districts, Shanghai. Resour. Sci. 2016, 38, 1503–1514. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Lu, S. Risk perception, ability of resisting risk and farmer willingness to exit rural housing land. Resour. Sci. 2018, 40, 698–706. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, P.; Zhao, K.; Zhou, S.; He, J. Risk expectation, social network and farmers’ behavior of rural residential land exit: Based on 626 rural households’ samples in Jinzhai County, Anhui Province. China Land Sci. 2019, 33, 42–50. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Azjen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action, Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Kuhi, J., Beckmann, J., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 1985; pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, traits, and actions: Dispositional prediction of behavior in personality and social psychology. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Berkowitz, L., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987; Volume 20, pp. 1–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Technol. 2020, 2, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Hansen, H. Determinants of sustainable food consumption: A meta-analysis using a traditional and a structural equation modelling approach. Int. J. Psychol. Stud. 2012, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sutton, S. Predicting and Explaining Intentions and Behavior: How Well Are We Doing? J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 28, 1317–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmmadi, P.; Rahimian, M.; Movahed, R.G. Theory of planned behavior to predict consumer behavior in using products irrigated with purified wastewater in Iran consumer. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 296, 126359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savari, M.; Gharechaee, H. Application of the extended theory of planned behavior to predict Iranian farmers’ intention for safe use of chemical fertilizers. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.-S.; Ooi, H.-Y.; Goh, Y.-N. A moral extension of the theory of planned behavior to predict consumers’ purchase intention for energy-efficient household appliances in Malaysia. Energy Policy 2017, 107, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Mosquera, N.; García, T.; Barrena, R. An extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior to predict willingness to pay for the conservation of an urban park. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 135, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.S.; Hon, A.H.; Chan, W.; Okumus, F. What drives employees’ intentions to implement green practices in hotels? The role of knowledge, awareness, concern and ecological behaviour. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinthal, D.; March, J.G. A model of adaptive organizational search. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1981, 2, 307–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintal, V.; Lee, J.; Soutar, G. Risk, uncertainty and the theory of planned behavior: A tourism example. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L.; Bearden, W.O. Crossover Effects in the Theory of Reasoned Action: A Moderating Influence Attempt. J. Consum. Res. 1985, 12, 324–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, A.; Gutscher, H.; Scholz, R.W. Psychological determinants of fuel consumption of purchased new cars. Transp. Res. Part F: Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2011, 14, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tonglet, M.; Phillips, P.S.; Read, A.D. Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to investigate the determinants of recycling behavior: A case study from Brixworth, UK. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2004, 41, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P.A. Understanding Information Technology Usage: A Test of Competing Models. Inf. Syst. Res. 1995, 6, 144–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, P.; Rise, J.; Sutton, S.; Røysamb, E. Perceived difficulty in the theory of planned behaviour: Perceived behavioural control or affective attitude? Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 44, 479–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cialdini, R.; Kallgren, C.; Reno, R.R. A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 24, 201–234. [Google Scholar]

- Hamann, K.; Reese, G.; Seewald, D.; Loeschinger, D.C. Affixing the theory of normative conduct (to your mailbox): Injunctive and descriptive norms as predictors of anti-ads sticker use. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 44, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, F.; Baines, J.T.; Taylor, C.N. Principles for ethical research involving humans: Ethical professional practice in impact assessment Part, I. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2013, 31, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nunnally, J.C. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. How age affects journalists’ adoption of social media as an innovation: A multi-group SEM analysis. J. Pract. 2019, 13, 537–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).