Urban Scene Protection and Unconventional Practices—Contemporary Landscapes in World Heritage Cities of Spain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Material and Method

2.1. The Area of Study

2.2. Design of the Study

2.3. The Empirical On-Site Study—Phases 1 to 4

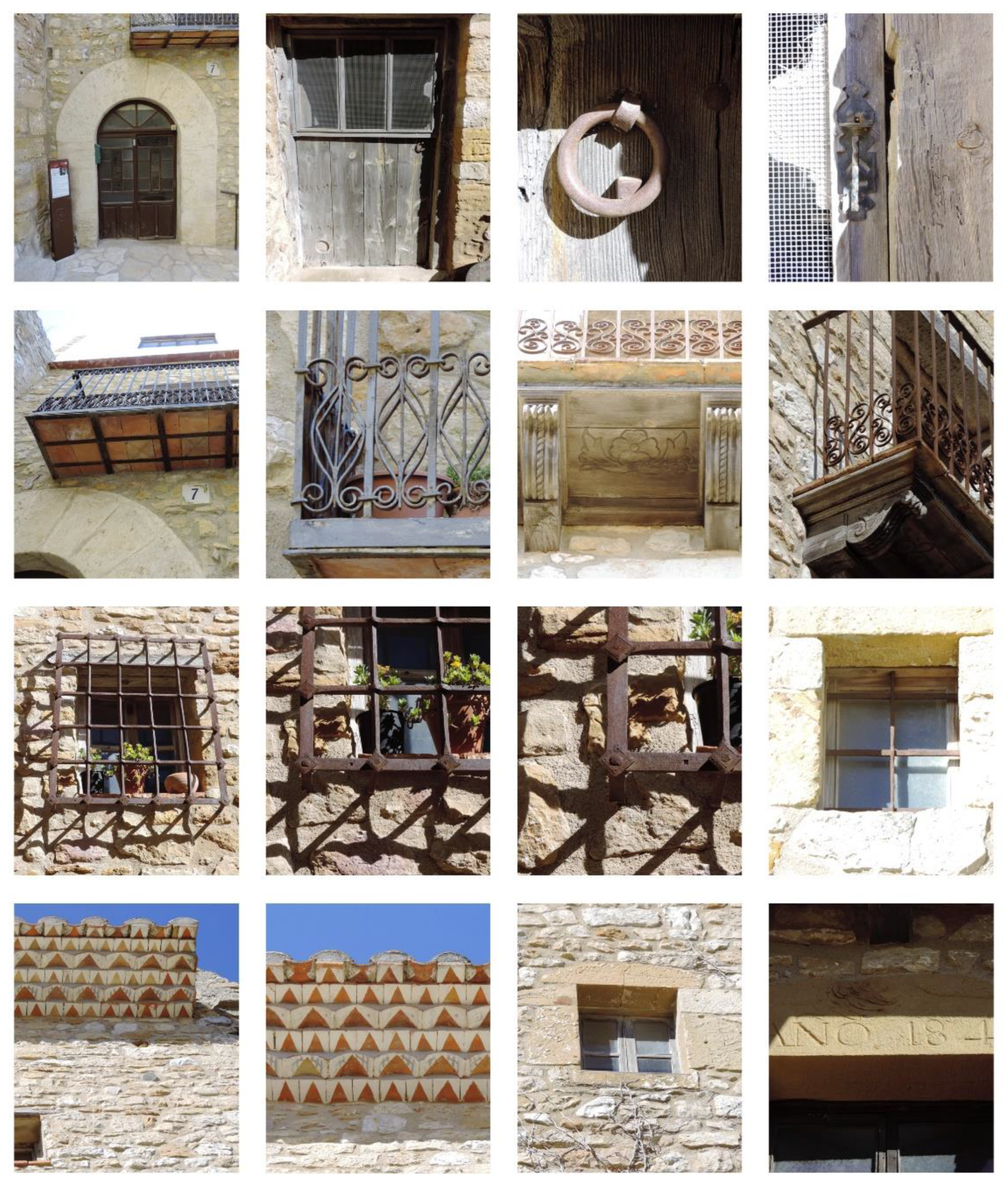

2.3.1. Phases 1 and 2—Identification and Categorisation of the Character

2.3.2. Phase 3—Stakeholders’ Interviews: Artisans and Neighbours

2.3.3. Phase 4—Data Digitisation

2.4. The Theoretical Approach—Phase 5

| Spain | City Inscribed in the WH List | Year | Criteria | HUL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ávila (Old Town) | 1985 | iii | iv | - | ||||

| Cáceres (Old Town) | 1986 | iii | iv | - | ||||

| Córdoba (Historic Centre) | 1984 | i | ii | iii | iv | 2 | ||

| Cuenca (Historic Walled Town) | 1996 | ii | v | - | ||||

| Salamanca (Old City) | 1988 | i | ii | iv | 1 | |||

| Santiago de Compostela (Old Town) | 1985 | i | ii | iv | - | |||

| Segovia (Old Town) | 1985 | i | iii | iv | - | |||

| Toledo (Historic City) | 1986 | i | ii | iii | iv | - | ||

2.4.1. (From) International Policies and Approaches

| Values | Definitions | Documents’ References |

|---|---|---|

| Historic | Historic value includes the knowledge of what has occurred in the past. It also encompasses the history of aesthetics, science, and society. A place may have historic value because it has influences or has been influenced by a historic figure, event, phase, or activity. | [48,49,50] |

| Cultural | Cultural value can be understood through both tangible and intangible heritage features, including historical, archaeological, architectural, fabric and material, technological, aesthetic, scientific, spiritual, religious, social, traditional, political, identity, relative artistic or technical rarity values, and aspects associated with human activities. | [17,27,48] |

| Intangible | Intangible values are memory, beliefs, traditional knowledge, and attachment to place. | [6,51] |

| Spiritual | The spirit of place comprises tangible (buildings, sites, landscapes, routes, objects, settlement patterns, and land use practices) and intangible elements (memories, narratives, religious beliefs, written documents, rituals, festivals, traditional knowledge, values, textures, and colours). | [6,49,51] |

| Social | Social value generates a concern for safeguarding heritage properties. It is related to traditional social activities, compatible present-day use, contemporary social interaction, and social and cultural identity. | [17,29,48] |

| Identity | Identity is reflected in the continuous evolution of cultural heritage properties, in their historical character, in both present and past values, and in their material fabric. It can also include age, tradition, continuity, memorial, legendary, wonder, sentiment, spiritual, religious, symbolic, political, patriotic, and nationalistic aspects. In terms of architectural features, it relates to townscapes, roofscapes, main visual axes, and building plots. | [17,27,49,51] |

| Cultural identity might include languages, societal structures, economic means, and spiritual beliefs. |

2.4.2. (To) National and Regional Policies and Standards

3. Results of the Theoretical and Empirical Work

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Recommendation Concerning the Safeguarding and Contemporary Role of Historic Areas; UNESCO: Nairobi, Kenia, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Spanish Government. Spanish Historic Heritage Law 16/1985. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/1985/BOE-A-1985-12534-consolidado.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- ICOMOS. Charter on the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas: ’The Washington Charter’; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Charter for the Protection and Management of the Archaeological Heritage; ICOMOS: Lausanne, Switzerland, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Québec Declaration on the Preservation of the Spirit of Place; ICOMOS: Quebec, QC, Canada, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. European Landscape Convention; Council of Europe: Florence, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Convention for the Safeguard of the Intangible Cultural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Khalaf, R.W. The significance of values: Heritage value typologies re-examined. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2018, 22, 466–481. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Asquith, L. Lessons from the vernacular: Integrated approaches and new methods for housing research. In Vernacular Architecture in the Twenty-First Century; Asquith, L., Vellinga, M., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2006; pp. 128–145. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, R. Heritage. Critical Approaches; Routledge: Oxon, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- García-Esparza, J.A. Are World Heritage concepts of integrity and authenticity lacking in dynamism? A critical approach to Mediterranean au-totopic landscapes. Landsc. Res. 2018, 43, 817–830. [Google Scholar]

- Schorch, P. Cultural feelings and the making of meaning. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2014, 20, 22–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, D.C. Heritage and scale: Settings, boundaries and relations. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2015, 21, 577–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. The Valletta Principles for the Safeguarding and Management of Historic Cities, Towns and Urban Areas; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Vienna Memorandum on World Heritage and Contemporary Architecture-Managing the Historic Urban Landscape. WHC.05/15.GA/INF.7. 2005. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/documents/5965 (accessed on 8 October 2020).

- UNESCO. World Heritage Cultural Landscapes. A Handbook for Conservation and Management; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape. 2011. Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/en/activities/638 (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Shaw, K. Independent creative subcultures and why they matter. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2013, 19, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oers, R. Managing cities and the historic urban landscape initiative. In Managing Historic Cities. World Heritage Papers 27; van Oers, R., Haraguchi, S., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2010; pp. 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- Altaba, P.; García-Esparza, J.A. The heritagization of a Mediterranean Vernacular Mountain Landscape: Concepts, Problems and Processes. Herit. Soc. 2018, 11, 189–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleakley, A. ‘Your creativity or mine?’: A typology of creativities in higher education and the value of a pluralistic approach. Teach. High. Educ. 2004, 9, 463–475. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D. Translating Space: The Politics of Ruins, the Remote and Peripheral Places. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 1102–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edensor, T. Waste matter—The debris of industrial ruins and the disordering of the material world. J. Mat. Cult. 2005, 10, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Council of Europe. Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society. Council of Europe Treaty Series, No. 199. 2005. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/1680083746 (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- UNESCO. The Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Re|Shaping Cultural Policies. Advancing Creativity for Development. Global Report; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Culture: Urban Future. Global Report on Culture for Sustainable Urban Development; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Altaba, P.; García-Esparza, J.A. A Practical Vision of Heritage Tourism in Low-Population-Density Areas. The Spanish Mediterranean as a Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5144. [Google Scholar]

- García-Esparza, J.A.; Altaba, P. Time, cognition and approach. Sustainable strategies for abandoned vernacular landscapes. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2712. [Google Scholar]

- García-Esparza, J.A. Beyond the intangible-tangible binary in cultural heritage. An analysis from rural areas in Valencia Region, Spain. Int. J. Intang. Herit. 2019, 14, 123–137. [Google Scholar]

- García-Esparza, J.A. Barracas on the Mediterranean coast. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2011, 5, 27–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, J. The Cultural Values Model: An integrated approach to values in landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 84, 127–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanwick, C. Landscape Character Assessment Guidance for England and Scotland; The Countryside Agency and Scottish Natural Heritage: Edinburgh, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wagtendonk, A.J.; Vermaat, J.E. Visual perception of cluttering in landscapes: Developing a low-resolution GIS-evaluation method. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 124, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, V.; Bottero, M.; Mondini, G. Decision making and cultural heritage: An application of the Multi-Attribute Value Theory for the reuse of historical buildings. J. Cult. Herit. 2014, 15, 644–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, M. Assessment of the decision-making process for re-use of a historical asset: The example of Diyarbakir Hasan Pasha Khan, Turkey. J. Cult. Herit. 2012, 13, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, R.; Rodríguez, F.J.; Coronado, J.M. Identification and assessment of engineered road heritage: A methodological approach. J. Cult. Herit. 2014, 15, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalkılıç, N.; Nabikoğlu, A. Documentation and analysis of structural elements of traditional houses for conservation of cultural heritage in Siverek (Şanlıurfa, Turkey). Front. Arch. Res. 2019, 9, 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, J.M. Methodological bases for documenting and reusing vernacular farm architecture. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, A. The Historic Urban Landscape Approach in Action: Eight Years Later. In Reshaping Urban Conservation. The Historic Urban Landscape Approach in Action; Pereira, A., Bandarin, F., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 21–54. [Google Scholar]

- Law, J. Organising Modernity: Social Order and Social Theory; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bianca, S. Historic Cities in the 21st Century: Core values and globalizing world. In Managing Historic Cities. World Heritage Papers 27; van Oers, R., Haraguchi, S., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2010; pp. 7–17. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, K. The Historic Urban Landscape paradigm and cities as cultural landscapes. Challenging orthodoxy in urban con-servation. Landsc. Res. 2016, 41, 471–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, G. Preservation, conservation and heritage: Approaches to the past in the present, through the built environment. Asian Anthropol. 2011, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsalloum, A. Rebuilding and Reconciliation in Old Aleppo: The Historic Urban Landscape Perspectives. In Reshaping Urban Conservation. The Historic Urban Landscape Approach in Action; Pereira, A., Bandarin, F., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 57–78. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Burra Charter for the Conservation of Places of Cultural Significance; ICOMOS: Burwood, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Declaration of San Antonio: Authenticity in the Conservation and Management of the Cultural Heritage. 1996. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/charters-and-texts/179-articles-en-francais/ressources/charters-and-standards/188-the-declaration-of-san-antonio (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- ICOMOS. Charter-Principles; Analysis, Conservation & Restoration of Architectural Heritage. 2003. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/charters/structures_e.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- ICOMOS. The Nara Document on Authenticity; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Nara + 20: On Heritage Practices, Cultural Values, and the Concept of Authenticity; ICOMOS: Nara, Japan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Khalaf, R.W. Continuity: A fundamental yet overlooked concept in World Heritage policy and practice. Int. J. Cult. Policy 2021, 27, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandarin, F.; van Oers, R. Reconnecting the City: The Historic Urban Landscape Approach and the Future of Urban Heritage; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Spanish Government. Safeguard of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Law 19/2015. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2015-5794 (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Valencian Government. Cultural Heritage Law 5/2007. Available online: https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2007-6119 (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Basque Government. Basque Cultural Heritage Law 7/1990. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2012/BOE-A-2012-2861-consolidado.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Basque Government, Basque Cultural Heritage Law. 2019. Available online: https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2019-7957 (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Castilla León Government. Cultural Heritage Law 12/2002. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2002/BOE-A-2002-15545-consolidado.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Castilla La Mancha Government. Cultural Heritage Law 4/2013. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/pdf/2013/BOE-A-2013-10415-consolidado.pdf (accessed on 24 September 2021).

- Jones, S.; Leech, S. Valuing the Historic Environment: A Critical Review of Existing Approaches to Social Value; University of Manchester: Manchester, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- ICCROM. People-Centred Approaches to the Conservation of Cultural Heritage: Living Heritage; ICCROM: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bandarin, F. Reshaping Urban Conservation. In Reshaping Urban Conservation. The Historic Urban Landscape Approach in Action; Pereira, A., Bandarin, F., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. The HUL Guidebook. Managing Heritage in Dynamic and Constantly Changing Urban Environments; a Practical Guide to UNESCO’s Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape. 2016. Available online: https://gohulsite.files.wordpress.com/2016/10/wirey5prpznidqx.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2021).

- Ripp, M.; Rodwell, D. The governance of urban heritage. In Historic Cities: Issues in Urban Conservation; Cody, J., Siravo, F., Eds.; The Getty Conservation Institute: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 549–555. [Google Scholar]

- De Cesari, C. World Heritage and mosaic universalism. A view from Palestine. J. Soc. Archaeol. 2010, 10, 299–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronner, S.J. Building tradition: Control and authority in vernacular architecture. In Vernacular Architecture in the Twenty-First Century; Asquith, L., Vellinga, M., Eds.; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2006; pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Upton, D. The preconditions for a performance theory of architecture. In American Material Culture and Folklife; Bronner, S.J., Ed.; UMI Research Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1985; pp. 182–185. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.O. How can we apply event analysis to material behaviour, and why should we? West. Folk. 1997, 56, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. The Implementation of the UNESCO Historic Urban Landscape Recommendation. In Proceedings of the International Expert Meeting, Shanghai, China, 26–28 March 2018; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/1953 (accessed on 8 October 2021).

- Pancholi, S.; Yigitcanlar, T.; Guaralda, M. Place making for innovation and knowledge-intensive activities: The Australian experience. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 146, 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lippard, L.R. The Lure of the Local: Senses of Place in a Multicentered Society; New Press: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

| Phase 1 | Phase 2 | Phase 3 | Phase 4 | Phase 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aim | Qualitative analysis | Organisation of data | Knowledge gathering | Digitalisation | Theoretical analysis |

| Activity | WH areas visual recognition | Categorisation and quantification | Face-to-face and online interviews | GIS database | Literature review |

| Outcome | Graphic register | Initial database | Transcriptions of space analysis | Empirical findings | Theoretical findings |

| Classification | Culling of elements | Information analysis | Analysis of the spatial distribution | Discussion of empirical and theoretical |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García-Esparza, J.A. Urban Scene Protection and Unconventional Practices—Contemporary Landscapes in World Heritage Cities of Spain. Land 2022, 11, 324. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030324

García-Esparza JA. Urban Scene Protection and Unconventional Practices—Contemporary Landscapes in World Heritage Cities of Spain. Land. 2022; 11(3):324. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030324

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía-Esparza, Juan A. 2022. "Urban Scene Protection and Unconventional Practices—Contemporary Landscapes in World Heritage Cities of Spain" Land 11, no. 3: 324. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030324

APA StyleGarcía-Esparza, J. A. (2022). Urban Scene Protection and Unconventional Practices—Contemporary Landscapes in World Heritage Cities of Spain. Land, 11(3), 324. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030324