Assessment of Critical Diffusion Factors of Public–Private Partnership and Social Policy: Evidence from Mainland Prefecture-Level Cities in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Theoretical Framework

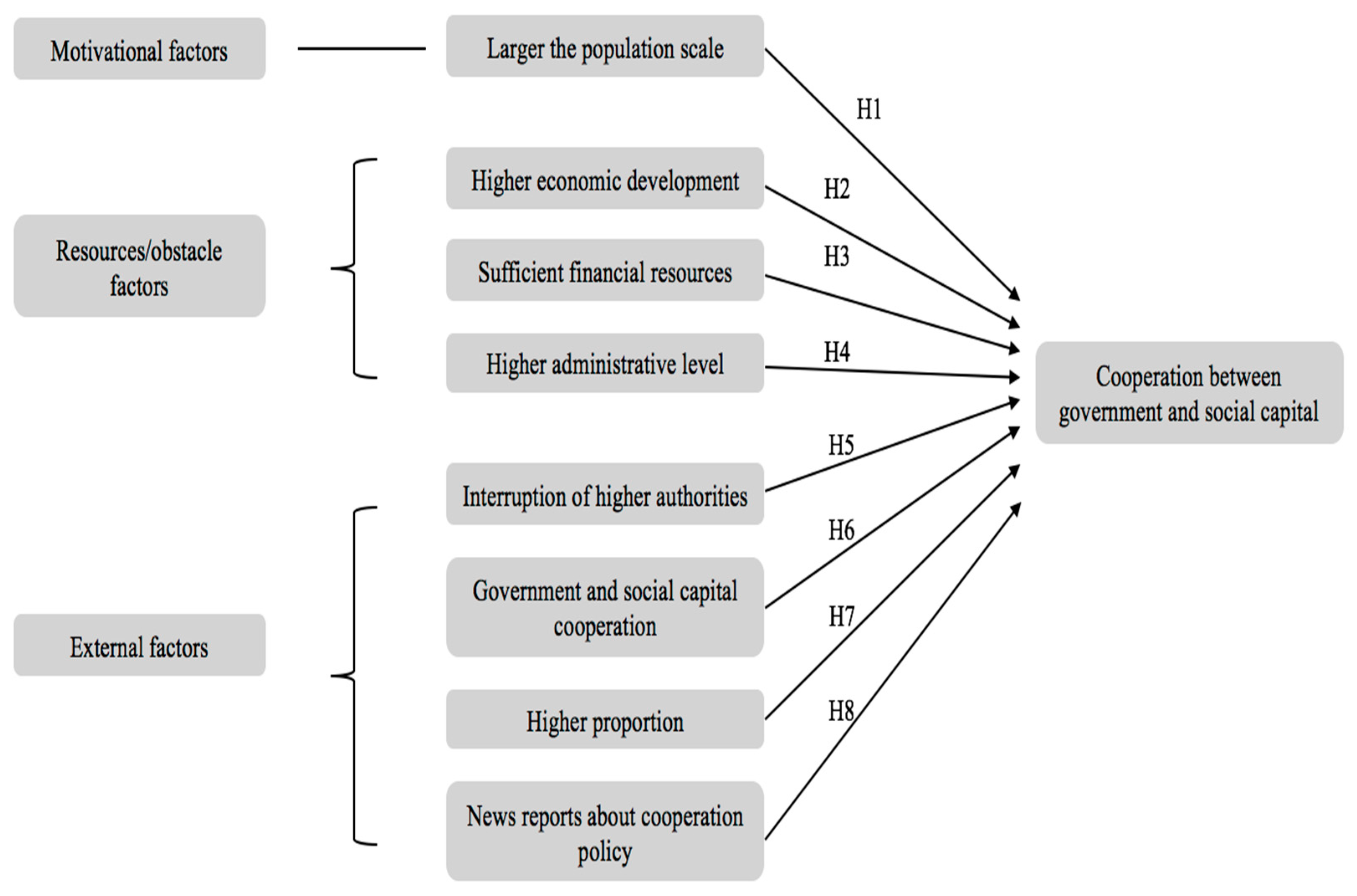

2.2. Hypothesis Development

2.2.1. Motivational Factor

2.2.2. Resources/Obstacle Factors

2.2.3. External Factors

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Sample Selection

3.2. Model

3.3. Variables

3.3.1. Dependent Variable

3.3.2. Independent Variables

3.4. Ethical Approval

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

4.2. Model Analysis

4.3. Robustness Test

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNKI | China National Knowledge Infrastructure |

| DOI | Diffusion of innovation |

| EHA | Event history analysis |

| GDP | Gross domestic product |

| PPP | Public–private partnership |

| OLS | Ordinary least squares |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| SE | Standard error |

References

- Wang, H.; Xiong, W.; Wu, G.; Zhu, D. Public–private partnership in Public Administration discipline: A literature review. Public Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narasimhan, R.; Aundhe, M. Das Explanation of Public Private Partnership (PPP) Outcomes in E-Government—A Social Capital Perspective. In Proceedings of the 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 2189–2199. [Google Scholar]

- Savas, E.S. Privatization and Public-Private Partnerships; Chatham House: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 9781566430739. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Westlund, H.; Liu, Y. Physical Capital, Human Capital, and Social Capital: The Changing Roles in China’s Economic Growth. Growth Chang. 2015, 46, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, C.; Xu, L. The relationship between PPP and government franchise and its legislative strategy. Financ. Res. 2016, 6, 78–85. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X. The relationship between franchise and PPP: Based on the background of developed countries. Financ. Sci. 2016, 6, 61–71. [Google Scholar]

- Xufeng, Z.; Hui, Z. Social Policy Diffusion from the Perspective of Intergovernmental Relations: An Empirical Study of the Urban Subsistence Allowance System in China (1993–1999). Soc. Sci. China 2018, 39, 78–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintrom, M.; Vergari, S. Policy Networks and Innovation Diffusion: The Case of State Education Reforms. J. Polit. 2015, 60, 126–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilardi, F.; Wasserfallen, F. Policy Diffusion: Mechanisms and Practical Implications. In Proceedings of the Governance Design Network (GDN) Workshop, National University of Singapore, Singapore, 17–18 February 2017; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Parkes, S.D.; Marsden, G.; Shaheen, S.A.; Cohen, A.P. Understanding the diffusion of public bikesharing systems: Evidence from Europe and North America. J. Transp. Geogr. 2013, 31, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmon, J. Public-Private Partnership Projects in Infrastructure; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; ISBN 9780511974403. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, D.M.; Volden, C.; Dynes, A.M.; Shor, B. Ideology, Learning, and Policy Diffusion: Experimental Evidence. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 2017, 61, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Wang, H.; Xiong, W.; Zhu, D.; Cheng, L. Public–private partnership as a driver of sustainable development: Toward a conceptual framework of sustainability-oriented PPP. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 1043–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Wang, H.; Song, J. Is space important to PPP: An exploration of spatial governance mechanism of PPP in China. Regul. Rev. 2018, 1, 102–115. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, J.L. The Diffusion of Innovations among the American States. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1969, 63, 880–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, F.S.; Berry, W.D. State Lottery Adoptions as Policy Innovations: An Event History Analysis. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1990, 84, 395–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gray, V. Innovation in the States: A Diffusion Study. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1973, 67, 1174–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.B. Determinants of Innovation in Organizations. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1969, 63, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovation, 3rd ed.; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 1–236. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, N.; Huggins, R.; Thompson, P. Social Capital and Entrepreneurship: Does the Relationship Hold in Deprived Urban Neighbourhoods? Growth Chang. 2017, 48, 719–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weible, C.M.; Sabatier, P.A. Theories of the Policy Process; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Haapanen, M.; Lenihan, H.; Tokila, A. Innovation Expectations and Patenting in Private and Public R&D Projects. Growth Chang. 2017, 48, 744–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, M.; Priyadarshee, A. Improving Service Delivery through State-Citizen Partnership: The Case of the Ahmedabad Urban Transport System. Growth Chang. 2015, 46, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-requena, G.; Molina-morales, F.X.; García-villaverde, P.M. The Mediating Effect of Cognitive Social Capital on Knowledge Acquisition in Clustered Firms. Growth Chang. 2010, 41, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jae Moon, M.; DeLeon, P. Municipal Reinvention: Managerial Values and Diffusion among Municipalities. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2001, 11, 327–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wejnert, B. Integrating models of diffusion of innovations: A conceptual framework. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2002, 28, 297–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shipan, C.R.; Volden, C. The Mechanisms of Policy Diffusion. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 2008, 52, 840–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouché, V.; Volden, C. Privatization and the diffusion of innovations. J. Polit. 2011, 73, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deep, A.; Kim, J.; Less, M. Realizing the Potential of Public-Private Partnerships to Advance Asia’s Infrastructure Development; Deep, A., Kim, J., Lee, M., Eds.; Asian Development Bank: Manila, Philippines, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Easton, D. An Approach to the Analysis of political Systems. World Polit. 1957, 9, 383–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Zhu, L.; Liu, C.; Chen, Y. TMT social capital, network position and innovation: The nature of micro-macro links. Front. Bus. Res. China 2019, 13, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X. Mandate Versus Championship: Vertical government intervention and diffusion of innovation in public services in authoritarian China. Public Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolbert, C.J.; Mossberger, K.; McNeal, R. Institutions, policy innovation, and e-government in the American States. Public Adm. Rev. 2008, 68, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, L.J.; Pickernell, D.; Thiomas, B.; Fuller, D. Innovation, social capital and regional policy: The case of the communities first programme in wales. Reg. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2018, 5, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habisch, A.; Adaui, C.R.L. A Social Capital Approach Towards Social Innovation. In Social Innovation; Osburg, T., Schmidpeter, R., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 65–74. ISBN 978-3-642-36539-3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X. The Institutional Logic of Collusion among Local Governments in China. Mod. China 2010, 36, 47–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, P. Local government innovation diffusion in China: An event history analysis of a performance-based reform programme. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2018, 84, 63–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhu, X. Multiple mechanisms of policy diffusion in China. Public Manag. Rev. 2019, 21, 495–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leisering, L.; Liu, T.; ten Brink, T. Synthesizing disparate ideas: How a Chinese model of social assistance was forged. Glob. Soc. Policy 2017, 17, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warsen, R.; Greve, C.; Klijn, E.H.; Koppenjan, J.F.M.; Siemiatycki, M. How do professionals perceive the governance of public–private partnerships? Evidence from Canada, the Netherlands and Denmark. Public Adm. 2020, 98, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Kan, Z. Private-sector partner selection for public-private partnership projects of electric vehicle charging infrastructure. Energy Sci. Eng. 2019, 7, 1469–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, H.; Shaheen, S.A.; Chen, X. Bicycle Evolution in China: From the 1900s to the Present. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2014, 8, 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Akintoye, A.; Edwards, P.J.; Hardcastle, C. Critical success factors for PPP/PFI projects in the UK construction industry. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2005, 23, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Song, L.; Xing, Z. Credit Default of Local Public Sectors in Chinese Government-Pay PPP Projects: Evidence from Ecological Construction. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2019, 2019, 2138525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Allison, P.D. Event History and Survival Analysis, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S. Applied Logistic Regression, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000; pp. 1–373. ISBN 0-471-35632-8. [Google Scholar]

- Cheevapattananuwong, P.; Baldwin, C.; Lathouras, A.; Ike, N. Social capital in community organizing for land protection and food security. Land 2020, 9, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Z.; Wei, Y.; Li, Q.; Lan, J. The mediating role of social capital in digital information technology poverty reduction an empirical study in urban and rural china. Land 2021, 10, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Huang, K.; Deng, X.; Xu, D. Livelihood capital and land transfer of different types of farmers: Evidence from panel data in sichuan province, china. Land 2021, 10, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y. From State to Market: Private Participation in China’s Urban Infrastructure Sectors, 1992–2008. World Dev. 2014, 64, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R. Gauging the stakeholders’ perspective: Towards PPP in building sectors and housing. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2020, 35, 1123–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Measures | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Adoption | 1 if the prefecture-level cities issue PPP-related policies; otherwise, 0. | Compilation of PPP Policies and Legal Documents, Pkulaw.cn |

| Population size * | Total population of prefecture-level cities at the end of the year | China Urban Statistical Yearbook |

| Economic development level * | GDP per capita | China Urban Statistical Yearbook |

| Government financial resources * | Per capita general budget income of local finance, i.e., general budget income of local finance/total population. | China Urban Statistical Yearbook |

| City administrative level | 1 for provincial capital cities and subprovincial cities, and 0 for ordinary prefecture-level cities. | Official website of the Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People’s Republic of China |

| Superior government pressure | 1 if the central government issued relevant documents; otherwise, 0. | Official website of PPP center of the Civil Affairs Ministry |

| Proximity effect | The number of neighboring prefecture-level cities adopting this policy earlier than it. | Pkulaw.cn |

| National proportion | The number of prefecture cities that have issued this policy nationwide divided by the total number of prefecture-level cities. | Pkulaw.cn |

| Number of news reports * | Number of news reports on this topic published in that year. | CNKI database |

| Variables | N | Min | Max | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adoption | 3239 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.085 | 0.278 |

| Population size | 3239 | 2.708 | 7.192 | 5.800 | 0.661 |

| Economic development level | 3239 | 7.415 | 12.456 | 9.928 | 0.788 |

| Government financial resources | 3239 | 3.969 | 10.260 | 7.031 | 1.090 |

| City administrative level | 3239 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.069 | 0.253 |

| Superior government pressure | 3239 | 0.000 | 1.000 | 0.216 | 0.412 |

| Proximity effect | 3239 | 0.000 | 19.000 | 1.860 | 2.715 |

| National proportion | 3239 | 0.000 | 0.952 | 0.128 | 0.182 |

| Number of news reports | 3239 | 4.663 | 7.916 | 5.852 | 0.949 |

| ADOPT | POPU | ECO | FINANCE | LEVEL | PRES | PROX | NATIONPRO | NEWS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADOPT | 1.000 | ||||||||

| POPU | 0.031 | 1.000 | |||||||

| ECO | 0.245 ** | −0.186 ** | 1.000 | ||||||

| FINANCE | 0.252 ** | −0.229 ** | 0.935 ** | 1.000 | |||||

| LEVEL | 0.045 * | 0.156 ** | 0.156 ** | 0.210 ** | 1.000 | ||||

| PRES | 0.487 ** | 0.007 | 0.405 ** | 0.416 ** | −0.056 ** | 1.000 | |||

| PROX | 0.455 ** | 0.096 ** | 0.362 ** | 0.331 ** | −0.138 ** | 0.608 ** | 1.000 | ||

| NATIONPRO | 0.578 ** | −0.004 | 0.361 ** | 0.344 ** | −0.071 ** | 0.732 ** | 0.810 ** | 1.000 | |

| NEWS | 0.531 ** | 0.002 | 0.178 ** | 0.187 ** | −0.031 | 0.842 ** | 0.584 ** | 0.743 ** | 1.000 |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population size | 1.191 * (0.099) | 1.989 *** (0.112) | 1.390 ** (0.130) | 1.661 *** (0.149) | |||

| Economic development level | 1.552 * (0.238) | 1.339 (0.246) | 0.948 (0.275) | 0.941 (0.279) | |||

| Government financial resources | 1.892 *** (0.173) | 2.523 *** (0.184) | 1.5575 ** (0.208) | 1.888 *** (0.217) | |||

| City administrative level | 1.082 (0.225) | 1.707 ** (0.239) | 0.226 *** (0.311) | 0.340 *** (0.333) | |||

| Superior government pressure | 1.218 (0.410) | 1.226 (0.411) | 0.740 (0.459) | 0.586 (0.469) | |||

| Proximity effect | 0.986 (0.031) | 0.964 (0.032) | 1.012 (0.032) | 0.975 (0.033) | |||

| National proportion | 6.093 *** (1.807) | 8.516 *** (0.582) | 6.109 *** (0.568) | 10.473 *** (0.591) | |||

| Number of news reports | 4.242 *** (0.205) | 4.206 *** (0.205) | 4.563 *** (0.209) | 4.581 *** (0.209) | |||

| Constant | 0.033 *** (0.586) | 0.00008 *** (1.367) | 0.000004 *** (1.173) | 5.1502 × 10−8 *** (1.640) | 6.0398 × 10−7 *** (1.402) | 6.3949 × 10−7 *** (2.146) | 6.8449 × 10−9 *** (2.553) |

| Chi-square | 3.194 * | 22.495 *** | 79.45 *** | 26.219 *** | 80.111 *** | 84.786 *** | 85.901 *** |

| df | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 8 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.002 | 0.15 | 0.495 | 0.177 | 0.499 | 0.524 | 0.531 |

| N | 3239 | 3239 | 3239 | 3239 | 3239 | 3239 | 3239 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Lv, Y.; Sarker, M.N.I.; Zeng, X. Assessment of Critical Diffusion Factors of Public–Private Partnership and Social Policy: Evidence from Mainland Prefecture-Level Cities in China. Land 2022, 11, 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030335

Li X, Lv Y, Sarker MNI, Zeng X. Assessment of Critical Diffusion Factors of Public–Private Partnership and Social Policy: Evidence from Mainland Prefecture-Level Cities in China. Land. 2022; 11(3):335. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030335

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xiaohan, Yang Lv, Md Nazirul Islam Sarker, and Xun Zeng. 2022. "Assessment of Critical Diffusion Factors of Public–Private Partnership and Social Policy: Evidence from Mainland Prefecture-Level Cities in China" Land 11, no. 3: 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030335

APA StyleLi, X., Lv, Y., Sarker, M. N. I., & Zeng, X. (2022). Assessment of Critical Diffusion Factors of Public–Private Partnership and Social Policy: Evidence from Mainland Prefecture-Level Cities in China. Land, 11(3), 335. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11030335