1. Introduction

The tradition of wooden architecture in Poland, is currently facing a serious threat caused by civilization processes that are occurring at an accelerated pace. The wooden architecture of cities and small towns has been almost completely replaced by brick, steel and glass constructions. Wooden architecture constitutes only 11.1% (over 6000 objects) [

1] of the protected architectural objects in Poland. The tradition of such technology is best sustained in rural areas. The resource of vernacular secular and sacral architecture in Poland has been relatively well recognized and described. Its importance is confirmed by numerous regional cultural routes of wooden architecture, as well as by three collective entries on the World Heritage List:

Churches of Peace in Jawor and Świdnica (2001);

Wooden Churches of Southern Małopolska (2003);

Wooden Tserkvas of the Carpathian Region in Poland and Ukraine (2013).

With its relatively young age, in comparison with vernacular buildings, the complex of wooden holiday architecture of the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries, inspired by the popular Western Europe Swiss style, has not met with such recognition or extensive scientific research.

The Swiss style in Poland, as in the countries of Central and Northern Europe, is present mainly in health resorts and spas, such as Nałęczów, Krynica-Zdrój, Polanica-Zdrój and Międzygórze. The wooden architecture of the Otwock area is an exception in comparison to the typical Swiss style buildings erected in the above-mentioned towns, and in the whole of Europe. Local social, historical, economic as well as natural and landscape conditions have left such a strong mark on it that distinctive features of the local architectural trend, identified with the term “Świdermajer”, have emerged. The unique historic value of the resource is also determined by the number of several hundred wooden buildings, representing distinctive features of the Świdermajer architectural trend, scattered along the railway line built in the second half of the 19th century along a stretch of several kilometers.

According to the 1999 ICOMOS Principles for the Preservation of Historic Wooden Buildings, developed by the International Wooden Committee ICOMOS, a coherent strategy for regular monitoring and management of the resource in the inevitable process of change is crucial for the preservation of historic wooden structures and their historical significance. There are a number of objectives that need to be defined and prioritized regarding the care and protection of the resource in reference to the concept of management, which aims to ensure the maximum longevity of wooden architectural heritage objects and the values they represent. Dynamic monument conservation understood in this way means planning based on interdisciplinary biological-technical and aesthetic-architectonic knowledge with regard to social sciences, such as ethnography, history or economics, but first of all the local building tradition. The first step towards organizing a system of protection for the resource in question takes the form of the research described in this article, which aims to identify and define the distinctive features of this resource.

1.1. Subject and Aim of Research

The article is based on the results of research conducted in 2019–2020, commissioned by the Mazovian Province Conservator of Monuments [

2]. The subject of the research was to identify a location and the distinctive features of the still preserved wooden holiday buildings, called ‘Świdermajer’ in the local architecture style, located in the area of the former summer resorts of the so-called ’Otwock Line’. By means of historical analyses, the study area was delimited by the former boundaries of the sub-Warsaw summer resorts established along the route of the Vistula Iron Railway completed in the second half of the 19th century.

The aim of the research is to create a substantive basis for the formulation of a strategic program of conservation for the wooden holiday architecture of the Otwock Line as a tool for the management of the historic resource by the Mazovian Province Conservator of Monuments. Despite the existence of articles contributing to the knowledge of this resource written since the 1980s and growing public awareness, the resource has generally remained outside the interest of the regional conservation office. Only a few objects were under conservation protection. The suburban settlements of the Otwock Line are today the subject of increasing investment pressure. Many wooden buildings are being renovated, rebuilt or, in extreme cases, demolished. Another serious threat to wooden buildings is fire. To date, no statistics have been kept on the scale of the transformation of the resource. Apart from a few collections of photographs documenting the general condition of selected objects, no attempts have been made to identify the resource. The present research is the first attempt to identify the resource and determine the scale of the phenomenon.

The research was divided into two phases. Only the first phase has been implemented to date and the main tasks (described in

Section 2, Materials and Methods) included:

The identification and verification of the resource;

The determination of the extent of the historic building pattern;

To carry out a typological assessment with an emphasis on the distinctive features of the “Świdermajer” style;

The indicate, on this basis, the most valuable structures and those requiring the most urgent intervention.

The first stage of research forms the basis for future work, which aims to define the objectives of conservation and protection activities, including:

The methods of monitoring wooden architecture;

The promotion of the wooden architecture heritage;

Indicating the directions for further research related to the topic.

1.2. A State of the Research

The first collective scientific publication dealing with the issue of the wooden architecture of the “Otwock Line” appeared in 1994 [

3]. It was the work of the Regional Research Team of Warsaw and Mazovia at the Monuments Documentation Centre. In the “Mazowsze” annual publication, the team led by Ewa Pustoła-Kozłowska attempted to evaluate and capture the stylistic features of the Otwock’s wooden architecture in its landscape and cultural context [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. Robert Lewandowski undertook the task of analyzing the origins of the sub-Warsaw villas in historical terms in his work published in 2011 [

2]. Andrzej Cichy’s study of wooden facade shuttering published in 2007 [

5] is an invaluable contribution too.

The history of summer resorts near Warsaw is closely related to the development of European tourism. The development of summer resorts near Warsaw is part of a well-described global phenomenon of dynamically developing “leisure” infrastructure, e.g., in 19th century Europe. While traveling for pleasure was already known in ancient times, it was only the social transformations and development of means of transport at the turn of the 19th to the 20th century that made this form of leisure time popular. This phenomenon has been widely described in scientific literature [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20].

1.3. Historical Context

In 1880, Michał Elwiro Andriolli, a well-known illustrator, a graduate of the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts in St. Petersburg and a student of St Luke’s Academy in Rome [

21], bought almost 202 hectares of land at the Świder river bank near Warsaw in order to build a summer resort colony. It was named Brzegi in 1883. In 1885, he bought materials and dismantled wooden ornaments from the pavilions of the Agricultural and Industrial Exhibition. Then, he built fourteen wooden villas for summer visitors with the help of the inhabitants of the Urzecz region (Olenders), who were well acquainted with carpentry techniques and lived in the nearby Świdry Wielkie colony. The buildings were lavishly decorated in line with Andriolli’s idea. In addition to the rich ornamentation, he also applied new, locally unknown technical solutions inspired by the timber frame constructions popular in Western European countries [

22]. He covered the wooden skeleton construction inside and outside with patches (battens) and filled the empty space with clay mixed with wood chips and finely chopped branches. When the outside and inside filling dried, the buildings were covered with sawn formwork. Unfortunately, none of the buildings has survived to the present day. Information about these summer houses comes from scarce iconography and press articles, where Andriolli boasted of his “ingenuity and inventiveness in construction” [

23].

The location was not accidental. The terrain conditions affecting the formation of ideal conditions for the establishment of the climate station (health resort) were defined by Andriolli’s friend, Dr. Henryk Dobrzycki, in numerous publications including “Sławuta—Klimatyczna stacja leśna oraz zakład kumysowy” (“Sławuta—a climate station and a kumis plant”) According to the medical knowledge of the time, the climate was of cardinal importance for the treatment of not only pulmonary diseases, but also general nervous exhaustion. The landscape of pine forests by the Świder River abounding with sand dunes, as well as the pine forest healing facility of Sławuta town, renowned since 1876 (currently located in Ukraine), met all the hygienic requirements for a climate station and summer resort.

According to Dobrzycki’s guidelines, an area located at or near a medium-sized river between pine forests was an ideal place for treatment and rest from urban nuisance, as in large forest areas, day and night temperature changes do not rapidly change as in open areas, as tree crowns retain heat, and the amplitude of day and night temperatures is smaller than in a forest-free area. The beneficial properties of pine resin ethers and pollen are considered an additional advantage of coniferous forests. In addition, forest air contains more ozone, the forest protects against strong winds and, according to Dobrzycki and contemporary hygienists, it is similar to the marine climate prevailing in northern Italy or southern France, popular destinations for consumptives in the 19th century. The occurrence of permeable grounds, light hills and terrain folds allowing for quick drainage after rainfall is also very important [

24]. The wooden buildings designed and erected by Andriolli in the 1880s are considered the prototype for the characteristic summer houses of the Otwock Line. However, attributing the authorship of the style of the Vistula River to Andriolli, despite his involvement in the execution of individual details, is unjustified [

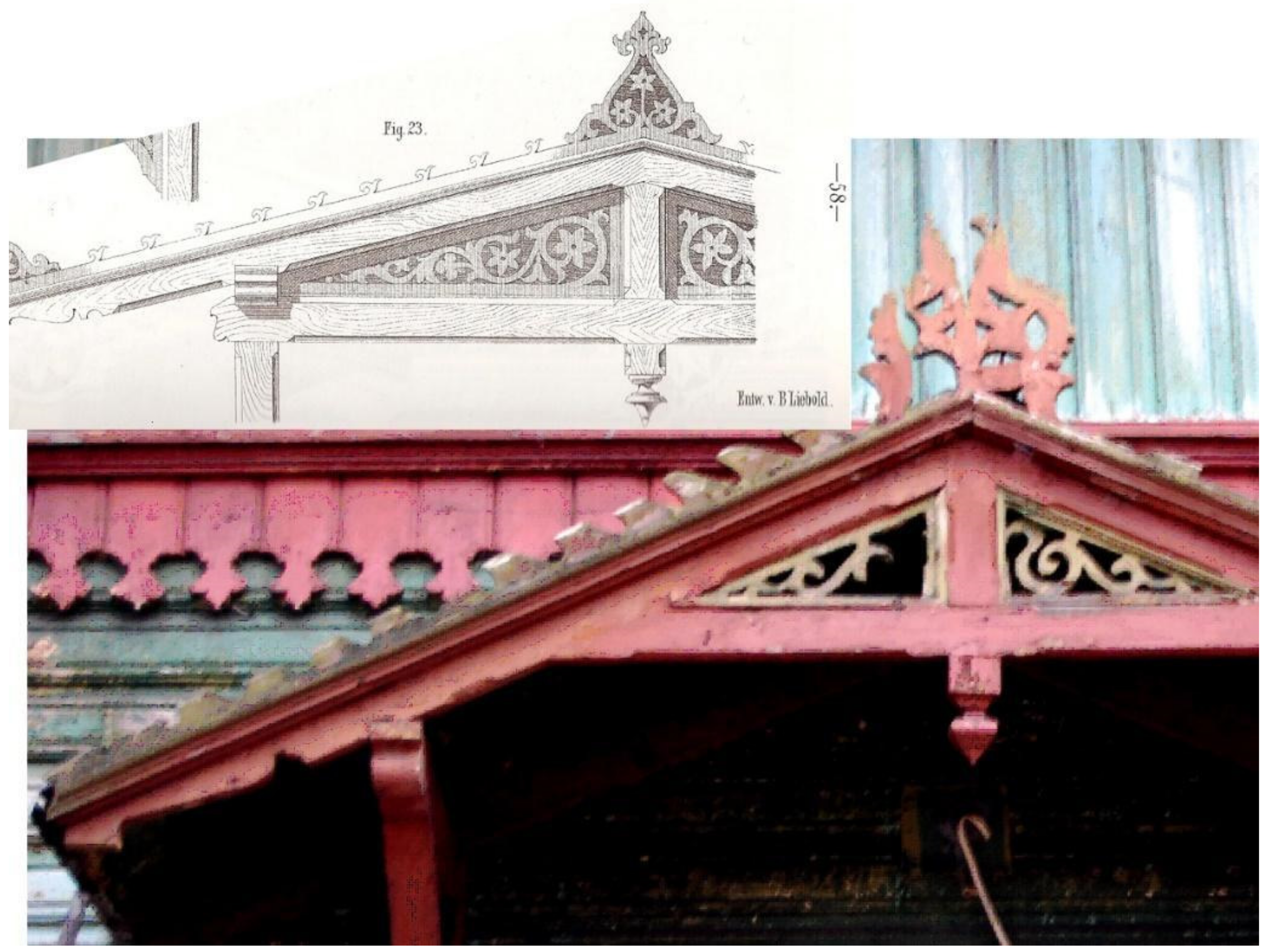

25]. Even then, the pattern books were widely used, e.g., the model book of woodcarving details by B. Liebold (

Figure 1) was published in 1893 and known all over Europe [

26].

The beginnings of the popularity of the wooden holiday architecture style on the banks of the Vistula River can be traced back to the social changes in the lifestyle of city dwellers and the development of railway public transport in the 19th century. At the beginning of the twentieth century, more and more Varsovians were looking for a place where they could spend summer outside the city, within natural surroundings, just as the richest among the landed gentry did in foreign resorts. One of the key criteria, however, was the price and the proximity to the city. While the family rested at the summer resort, the father could commute to them at weekends or even, owing to the development of the railway network, after work. August 1877 saw the opening of the Vistula Iron Railway line (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Otwock was the first station in the eastern direction after Prague (the district of Warsaw). In the following years, new stations were built along this section, giving rise to new summer resorts: Świder, Anielin, Jarosław, Józefów, Emilianów, Michalin, Falenica, Miedzeszyn, Miedzeszyn Nowy, Radość, Zbójna Góra/Daków, Międzylesie, Anin. The Vistula River also provided transport opportunities, with passenger ships traveling from Warsaw. In the early 20th century, a narrow-gauge railway line running parallel to the Vistula Railway provided an additional convenience. The building movement, which mainly boiled down to the construction of more and more wooden holiday villas, concentrated around the established railway stations, determined the creation of a characteristic linear settlement structure, called the Otwock Line.

In 1868, Ernst Gladbach’s first publication describing the “Swiss style” was released [

27]. It contributed to the popularization of Swiss architecture in the entire Europe as well as to the establishment of the notion of the “Swiss style” [

28]. Wooden villas inspired by the first designs of Andriolli, built in a style echoing the Swiss style, popular among European resorts, were enchanting with the rich ornamentation of wooden openwork. Exotic to the Mazovian landscape, they were usually placed in wide, deep gable eaves, decorated with story verandas, lambrequins and balusters. The majestic character of the buildings with high knee walls, allowing the attics to be adapted for residential purposes, competed for their place in the forest landscape of Otwock and its surroundings with lofty pine trees and more and more dense new residential and commercial buildings in that area. The first half of the 20th century was the peak period of the development of the summer architecture of the Otwock Line, which lasted until the outbreak of the Second World War. In one of his poems, Konstanty Ildefons Gałczyński jokingly referred to the style of the wooden architecture by the Świder river, arranged for the new bourgeoisie, as “Świdermajer” [

29]. The name was adopted and has remained a local identifier of the wooden architecture of the Otwock Line until today.

In 1916, Otwock was granted municipal rights, and at the beginning of 1924, it received the status of health resort, which significantly translated into the popularity of the summer resort among Varsovians. Based on a guidebook of the time [

30], in 1925, in Otwock, there were 2 hotels, 40 guest houses, 1300 villas, 3 restaurants and 5 eating places with the number of rooms amounting to 4480. The establishment of the first hygienic and dietetic institution for Jews, founded by Władysław Przygoda in Otwock in 1895, was an important event for the development and the cultural landscape of the Otwock summer resort. The Jewish population grew systematically from that time until World War II. In 1916, Otwock obtained town rights and the Jewish population grew to approx. 20% of the town’s inhabitants; in 1939 the number rose up to 55% [

4]. The tragic events of World War II and the later political changes caused most of the wooden buildings to be taken over by the communist state.

Despite the destruction caused by World War II and the changes in the ownership structure due to political developments during the communist period, several hundred wooden buildings representing the local architectural trend, commonly referred to as ’Świdermajer’, have survived to this day.

3. Analysis of the Resource Value

Recreation and entertainment in summer resorts, at the turn of 19th to the 20th centuries, were only an addition to the therapeutic role that was played by staying in an appropriate and beneficial climate. The specific function of the villas near Warsaw required a special architectural setting. As a result of the construction movement, at the end of the 19th century, a local architectural style emerged, drawn from both Western and Eastern patterns. Its special feature was the arrangement of utility functions, adapted to the requirements of the summer function, which is reflected in the characteristic shape of the wooden buildings.

Already in his first small three-axis house, Andriolli used details known from the “Swiss style”, popular in Western summer and health resorts. Although Andriolli’s workshop itself is undecorated, the houses moved and built from the exhibition pavilions are more ornamented, although the technology of wall construction differs significantly from the later frame-based villas. Exhibition pavilions were quite ornate and architecturally refined, as companies ordered them also from famous architects (e.g., the Jung brewer’s pavilion designed by Witold Lancie) [

31]. The Alpine style was popular and well-known in Warsaw and was associated with entertainment in the largest open-air salon of Warsaw at that time, the Swiss Valley opened in 1827 in Ujazdów, with its numerous pavilions and cafés decorated in Alpine style. Apart from the medicinal and social needs, it should also be noted that the popularity of the Romantic movement among Warsaw’s bourgeoisie resulted in nature and wilderness no longer being perceived as a sinister, threatening force, but being appreciated as a space for relaxation and rest from the hustle and bustle of the city. The press, describing the journeys of the “exquisite company” traveling to fashionable European resorts, generated the need to relax in lesser-known places, but closer to the capital, i.e., located no more than an hour’s train ride away.

The rapid development of summer resorts required the use of cheap materials that would allow for a quick construction and comply with the increasingly common hygienic requirements. This material was commonly available and took the form of cheap wood coming from the forests cut down in the landed estates impoverished as a result of the post uprising repressions. The Anielin-based Kurtz family from Otwock Wielki, as well as the Wiąz and Glinianiec, became such estates for the Otwock Line. The allotment of land for summer resorts was initiated by Elwiro Michał Andriolli.

According to Henryk Dobrzycki, in his draft of the sanitary legislation for health resorts [

32], the rooms for summer visitors should be at least three-square fathoms (about 6.4 m

2). The villas were also supposed to be well lit, equipped with verandas, which made it possible to rest outdoors on a rainy or too hot day. The rooms of villas and guest houses were also to be perfectly ventilated to ensure access to healthy “climatic” air. Additionally, the “ethers” of fresh pine wood, from which the outer walls of villas and pensions were built, was of great importance at a time when inhalation and aromatherapy were becoming popular. Thus, all the advantages of the villas built in the summer resorts near Warsaw on the Otwock Line were the answer to the inconveniences of living in Warsaw tenement houses. The differentiation from the local rural housing, creating the illusion of a journey to distant lands, was a great advantage.

As a result of the popularity of Andriolla’s “Brzegi”, other colonizers appeared within time. Initially, the villas were built on the Świder River. One of the first is “Bojarów” founded in 1883 by Konstanty Moës Oskragiełło; although the main "mansion" is made of brick, there are also two wooden houses. There was already a high increase in investment interest from the mid 1880’s. Around the station in Otwock, until 1893, around 60 villas had been built for summer visitors and as villas owned by the Warsaw intelligentsia. Among others, Władysław Marconi had four apartments in two wooden houses to be let for holidaymakers. The kitchen was located in a separate building. This applied to most of the villas. This changed in the period after the Great War, when, with the increase in prices by about 50 percent, a drop in the value of gold by half and an increase in the number of summer visitors from poorer strata, the most sought-after rooms were those equipped with their own kitchen.

Villas built in the way known as the Swiss style were popular in summer resorts, captivating with the rich ornamentation of wooden openwork, usually placed in wide, deep gable eaves, with their decoration of floor verandas, lambrequins, balusters, and the majesty of buildings elevated with a high knee wall, allowing for the future adaptation of the attic for residential purposes.

Each villa had its own name and often a decorative accent distinguishing it from other buildings. The rich ornamentation decorating the tops of houses, verandas and windows of resorts throughout Europe had to appear on the Świder river as well. There was competition for openwork decorations. Excellent local carpenters of Olender (Dutch) origin used thin blades to make ornaments with floral, geometric and even symbolic motifs. The geometric rhythm of the profiled shuttering boards arranged in various patterns completed the whole. Fully nutritious wood of shuttering boards profiled in dozens of ways, impregnated with linseed oil, even after a hundred years, has retained its technical and functional properties. The formwork of one profile was used within one villa, usually for pragmatic reasons. However, there were structures with a greater variety of profiles, as in the case of the Gurewicz Spa, where during the restoration research, five different profiles of shuttering were identified. The profiles used, due to the pattern, thickness and width of the shuttering board, can be helpful in dating the buildings [

25]. The shuttering boards occur in a vertical arrangement, protecting the gable walls from the wind, and in a horizontal arrangement referring to traditional buildings with a log construction. Moreover, as in other regional styles derived from Alpine architecture, the boards are fixed directly on the supporting elements of the structure [

19]. An important technological contribution, which made the widespread use of openwork decorations possible, ought to be mentioned. In the second half of the 19th century, with the development of metallurgy and the production of resilient saws on an industrial scale, ornaments cut with a hacksaw appeared.

It is worth mentioning that they were not designed by architects. The analysis of the preserved architectural projects and field inventories leads to the conclusion that, in almost every case, the ornaments were either not included in the design or were left to the free interpretation of carpenters using their own ideas and templates. Therefore, the influence of high-class carpenters of Olender origin (e.g., the Jesiotr family from Górki) on the architecture of summer resorts located in the Vistula valley should not be overlooked.

Along the Otwock Line, a unique style of erecting holiday villas appears. While the character of large boarding houses is similar to that in other health resorts and summer resorts, resulting from their functional requirements, Line a characteristic style can be distinguished within the territory of the Otwock, subordinated to the specific Warsaw metropolitan clientele, looking for recreation with their friends in smaller structures. Despite preserving a large number of designs (only for Otwock), it is difficult to unequivocally attribute specific works to well-known architects, as the search revealed that the designs were created in Warsaw ateliers of lesser-known authors and teams.

One of the identified buildings, which can be attributed to a famous architect, is the villa of Odo Bujwid (

Figure 6), located at number 19 Kościelna Street in Otwock, designed by Stefan Szyller in 1888 [

33,

34]. The building is a typical example of a single-story villa, which was eagerly copied in the summer resorts of the Otwock Line. This one-story, five-axis villa has a symmetrical layout, with a pair of shallow front risalitas and a veranda on the axis and two smaller verandas on the outer axes facing the yard, evidently situated in the center of the forest garden. The gables and verandas of the villa are richly decorated with fretwork with floral motifs. The interior layout is not typical of other one-story buildings, because it has a two-line system with a hallway on the axis. Usually, in later designs made for renting to summer visitors, and not as own villas, the main veranda on the building’s axis is connected to a living room or a day room. Two verandas are attached to the gable walls. On the north side, there is mostly an entrance to the vestibule, usually covered by a small canopy. This was due to the need to provide a veranda for each set of rooms intended for summer visitors, commonly a bedroom and a living room.

In the buildings occurring in Western summer resorts and in the Alps, erected in the Swiss style due to the availability of material, the main body is made of stone or brick. In German, Galician and Silesian boarding houses, cloister or balcony terraces usually surround the building on the side of the gable wall, hidden under the overhang of the wide gable eaves, protruding considerably behind the wall face. Additionally, this part of the building is oriented in the south or south-west direction. Leisure villas on the banks of the Vistula River were oriented in the south-west direction with the front wall usually having five or more axes in order to provide access of light to verandas surrounding the building from three sides. This is a procedure that cannot be replicated in large western guest houses with more than eight apartments.

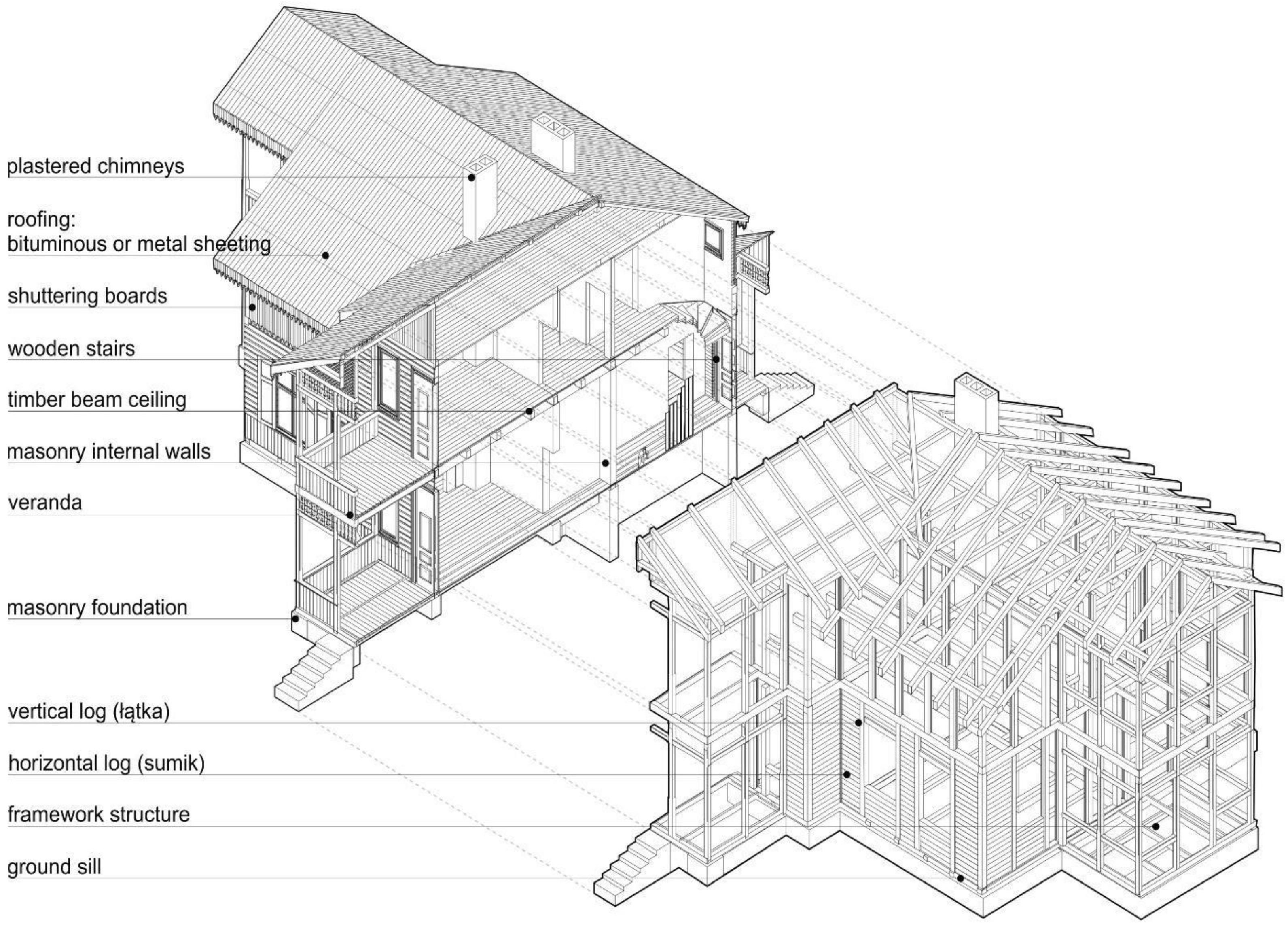

The type of villa, most commonly represented in the summer resorts of the Otwock Line near Warsaw, is the two-story version of the described five-axis villa, with two-story verandas and a representative staircase in the extended hallway (

Figure 7). In both presented types, there is a high knee wall, which allows for the usable adaptation of the attic and to enlarge the villa in the future by adding rooms in the attic by breaking window openings in the roof and insulation of knee walls and the roof. In the discussed area, there are also numerous villas with a two-story main body and one-story wings, with a tile roof, where the gable walls of the main body form the front of the villa enriched with a balcony or a two-story veranda. Villas echoing the style of Italian villas, equipped with a tower, which was an extension of the staircase, were also popular. The tower allowed people to admire the landscape and sometimes had only decorative function or provided light for the staircase. This is a group of buildings with the most varied shape and layout, which can also be found in many other summer resorts in the country.

What is worth mentioning is the importance of railway architecture in the development of summer resorts. Richly decorated wooden railway stations in Otwock, Świder, and Józefów were built on the wave of the popularity of the Swiss style as a proposal for railway architecture along rapidly developing lines. The railway had to reach the summer health resorts, both in Prussia and Austria, as well as in the Russian annexation, although here railway stations were popularly located outside the urban fabric for strategic reasons. Summer resorts developed around the stations took the form of a showcase of the resort and a kind of gateway to the town. It is therefore impossible not to consider the influence that the architecture of the train stations may have had on the appearance of the surrounding villas.

The relationship between the architecture of wooden villas and the landscape of a pine forest located among forest dunes on dry ground cannot be overlooked either. Although walking paths (usually oval in shape) or flowerbeds (commonly in the immediate vicinity of the villas and boarding houses) were created, the gardens surrounding the villas created an impression of naturalness.

While analyzing wooden villas that are unique to Mazovia, attention is usually paid to their specific formal features (shape, ornament, and surroundings), or the historical figures associated with these buildings. It is worth noting that they represent not only values recognized individually for each object, but, as a set, they document the processes of social changes occurring in Poland at the turn of the 19th to the 20th centuries, focusing, as if through a lens, in Warsaw and its surroundings. These processes had a direct or indirect impact on the development of the characteristic features of the wooden “Swidermajer” buildings and can be divided into contextual factors, including historical, social, economic, artistic, landscape, technical, sanitary, and even ethnographic (e.g., the presence of Olender carpentry workshops/teams located on the border of the emerging summer resorts).

The scale of the social phenomenon involving the development of summer cottages near Warsaw resulted in the fact that, despite the numerous losses of the resource due to war damage and post-war negligence, the resource may still be perceived as a dispersed historic complex of the wooden building pattern.