Abstract

We conceptualize typical rural communities in China as diversified economic clusters. In normal times, economic actors in these communities rarely cooperate with each other, but are integrated into separate commodity chains. These “diversified clusters”, however, show resilience and flexibility when an external shock—the COVID-19 pandemic—disrupts the spatial connections throughout the existing commodity chains. In this study, we use primary field data collected from one typical rural community in Northern China to show how economic diversity, aided by social networks and space-shrinking technologies, allowed for the vertical commodity chains to be reconfigured temporarily into localized horizontal commodity networks to cope with the emergencies brought about by the pandemic. Our findings suggest that while market integration can create precarity at the individual level, it can also contribute to economic resilience at the community level if it increases economic diversity and complementarity within the community. This study sheds lights on discussions of the resilience of rural and economic clustering by a novel conceptualization of diversified clusters and also offers a nuanced understanding of the connection between market integration and community resilience.

1. Introduction

The greatest disruption brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic to the global economy is arguably the suspension of the circulation of capital, labor, and commodities along commodity chains, caused by the various mobility restrictions from the international level down to grassroots communities [1,2]. As rural communities in the Global South are now increasingly being integrated into commodity chains at regional, national, or even global scales [3,4,5], the pandemic has had disruptive impacts on various aspects of the rural livelihoods [6,7,8,9]. A corollary from these observations is that, compared with rural communities that are more subsistence-oriented and self-reliant, those where the economic activities and livelihoods are more integrated into markets will experience greater disruption and negative impacts during the pandemic, even though they are economically better off under normal circumstances. In this sense, the shocks brought about by the pandemic have further exposed the potential adverse impacts of market incorporation [10]. For rural communities and residents, market integration and economic diversification (from agriculture) have a trade-off: while they may expand employment opportunities and economic returns and thus reduce vulnerability as “inherited exposure”, they also increase precarity—as “produced exposure” to market risks and a new form of vulnerability [11].

In this study, we try to further the examination of this relationship between market integration on the one hand and precarity and resilience on the other by investigating how different types of market integration can shape the economic resilience of rural communities when coping with external shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, we present a case study of how a typical rural community in Northern China coped with the emergencies brought about by the pandemic. Conceptualizing this type of community as a “diversified economic cluster”, we show that (1) deep market integration exposed all residents to disruptions—albeit in differentiated ways and to uneven extents, and (2) the diversified economic structure in the community, however, aided by existing social networks and space-shrinking technologies, allowed for the circuits of commodities to be reconfigured to form local commodity networks, providing the community with an adaptive mechanism for effectively coping with urgent challenges during the crisis.

In industrial clusters, firms specializing in the same industry congregate spatially to create collective advantages and cooperate to enhance their competitiveness. In contrast, rural communities that are diversified clusters gain flexibility and resilience from the spatial clustering of a diverse set of sectoral specializations, organizational forms, and employment activities. While the restrictive measures imposed during the pandemic put the community—like all others across rural China—in spatial isolation, the community has the social efficacy, physical and technological infrastructure, and economic flexibility to organize localized circuits of commodities to address urgent needs. Overall, we find that the economic impacts of the pandemic on the community have been mostly moderate and temporary, partly thanks to the effective responses at both national and local levels and the prompt return to normalcy.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the literature on economic clustering in the rural economy and its implications for resilience. In Section 3, we describe the patterns of economic clustering in rural China, which we summarize as “diversified clusters”. Section 4 introduces the research site and our methodology. Section 5 first outlines the national and local responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, presenting the macro-level context for the case study, and then documents the economic impacts of the pandemic on the case village. Section 6 details how commodity networks were reconfigured to address urgent economic needs in the community during the pandemic, and Section 7 presents theoretical and practical implications and concludes the paper.

2. Economic Clusters and Community Resilience

Industrial clustering is a central theme in economic geography [12,13]. The discussion of the rationale for and advantage of industrial clustering dates back to Alfred Marshall [14], who found four types of effect that clustering could bring to residing enterprises: reduction of transport costs, provision of skilled labor, infrastructure sharing, and facilitation of information communication. The advantages that industrial clustering can bring to firms and to regional development have been widely documented across the world, and clustering of industries has become a policy prescription for promoting regional economic growth [12,15].

The model of industrial clustering has also been adopted to boost rural and agricultural economic growth [16,17,18,19]. For instance, inspired by the One-Village-One-Product (OVOP) initiative from Japan, other Asian countries, such as Vietnam [20], Thailand [21], and China [22], have tried to promote this model in their rural economies. The success rate of this model, however, has been low. As both the “multifunctionality” debate in the rural setting of the Global North and the “de-agrarianization” discussion in the Global South show, the economic structure in rural areas across the world remains, at best, diversified rather than specialized and, in most places, disorganized and uncoordinated [5,23,24]. Studies across the world have shown that rural households’ integration into markets and transition out of farming, which mainly occurs through labor commodification, is a highly uneven process that typically creates pluriactivity and plurilocality at the household level [4,25,26,27]. In the Global South in particular, the livelihood diversification by rural households has changed the rural economy from a localized subsistence-oriented agrarian economy to one characterized by occupational diversity, de-agrarianization, and spatial delocalization [3,28,29].

The literature on economic clusters so far has not paid much attention to the connection between the structure and characteristics of economic clusters and resilience. Resilience denotes the capacity and the processes with which an existing system endeavors to maintain basic functions in the face of external stresses or disturbances [24,30]. The social science literature on resilience has proposed a variety of conceptualization of resilience. Some see it as the ability of a system, a group, or a community to “get back to normal”—retaining basic functions in the disruptive state or returning to an equilibrium state after the disruption—while others see it as an ability to adapt to external changes and, instead of returning back to normal, evolve in open ways into unpredicted outcomes [31,32]. Resilience is also assessed at multiple scales, ranging from global and national to community, household, and even individual levels. In this study, we focus on resilience at the community level [32,33]; specifically, how rural communities in China, as economic clusters, when facing the economic and social disruptions brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, manage to devise coping strategies and re-organize resources to retain basic functions and meet urgent needs.

On this connection between a community’s characteristics as an economic cluster and its resilience in the face of external disturbances, two key findings from the literature are worth noting. First, economic diversity positively contributes to community resilience. Economic diversity reduces the community’s over-reliance on specific sectors, resources, or markets and, in turn, its vulnerability to external shocks in those areas [32,34,35]. A diversified local economy also provides more substitutable resources and greater possibilities of re-organizing these resources, increasing the community’s adaptive and innovative capacities in the face of uncertainties and unknown challenges [31,36]. These findings suggest that forming a specialized economic cluster, while gaining advantages in efficiency and competitiveness, tends to reduce the community’s resilience and expose it to greater vulnerabilities [19,37].

Second, the economic resources, which are mostly under private individual ownership, can only be mobilized to provide collective solutions to disruptions when the community has adequate social capital and thus social efficacy [38,39]. Social capital—in the forms of social networks, mutual trust, and norms of reciprocity within the community—can enable resource sharing across community members, coordinate collective actions, provide immediate assistance to those affected, and acquire supplies and help from external sources [34,38].

In synthesizing these findings on community resilience, Geoff Wilson [32] argues that it is the effective interactions between economic resources, social capital, and other conditions such as political governance and environmental resources that generate resilience at the community level. Applying this insight onto the research question of this paper, we thus hypothesize that rural communities that are diversified economic clusters and have a healthy stock of social capital will show resilience in the face of the disruptions brought about by the pandemic and effectively devise coping strategies to retain basic functions.

3. Rural Communities in China as “Diversified Clusters”

Similar to elsewhere in the Global South, the rural labor force in China also went through a prolonged process of de-agrarianization—only on a more massive scale—mainly through labor migration to cities in search of wage jobs [40]. By the end of 2019, there were 291 million rural migrant workers, constituting 53% of the total rural population of 552 million [41], and over 99% of the rural migrant workers were working in non-agricultural sectors, indicating a persistent trend of labor force de-agrarianization. As a result of this transformation, rural households in China share many characteristics with their counterparts in other developing countries; their livelihoods are highly diversified, with members employed across both the agricultural–industrial sectoral divide and the urban–rural social–spatial divide, arranged through gender and generational division of labor [42,43,44].

There are, however, distinctive aspects in rural China’s development experiences. First, in the first two decades after the de-collectivization reform started in the late 1970s, rural China experienced a successful rural industrialization led by the rapid growth of township-and-village enterprises, unparalleled elsewhere [45]. As a result of this, rural China has a much higher level of industrial development and far greater industrial employment opportunities than other developing countries [46]. In comparison, in other developing countries, while the rural labor force has become de-agrarianized through migration and livelihood diversification, the rural economy remains predominantly agrarian, with little non-farm employment available locally [47].

In the process of rural industrialization, some local governments in China actively promoted the growth of a particular industry and fostered the formation of industrial clusters [48]. In more recent years, local governments have also tried to develop “specialized villages” where the majority of households specialize in the production of a particular agricultural or industrial product [22,49]. Despite these efforts, these agro-based specialized villages or rural industrial clusters remain the exception rather than the norm. By one account, by the end of 2016, rural China had 60,473 specialized villages, where 80.4% of households in these villages undertook specialized production, covering nearly 17.5 million rural households [50]; yet, these constitute only 2.3% of the 2.6 million natural villages and approximately 10% of the administrative villages in China.

Aside from the successful industrialization, the agrarian transition in China has also unfolded in unique ways. Not only has smallholding family farming in China been dissolving more rapidly than in other developing countries, but there is also a more diverse set of new capitalist producers emerging in Chinese agriculture [29]. Specialized family farms (either in independent production or in contract farming arrangements), large-scale capitalist agribusinesses, and agricultural cooperatives have all grown to a significant scale and often exist within the same locality [51]. In particular, unlike in many other developing countries where the capitalist agriculture is typically dominated by large-scale, transnational agro-capital and the domestic agrarian capitalist class that emerged “from below” is weak and small [52], in China domestic non-agrarian capital has expanded rapidly into agriculture and an indigenous agrarian capitalist class that is growing in size and political-economic power [53,54,55].

Together, the three key developments in rural China described above—the deep penetration of commodity and market relations into rural livelihoods and the diversification that follows, the high level of local industrial development in many rural areas, and the diverse pathways of agrarian transition and the emergence of a diverse set of new capitalist producers—have created an economic structure in many rural communities in China that we call a “diversified economic cluster”. In these diversified clusters, not only have rural households diversified their livelihoods across employment activities and spatial locations, a common pattern found across the Global South, but the local economy has also diversified across economic sectors, with a significant presence of non-agricultural employment. Furthermore, within both the farm and non-farm sectors locally, there is a diverse set of organizational forms of production, including labor-hiring firms, independent family production, self-employment, contract and out-sourcing arrangements, and cooperatives.

In a typical industrial cluster, firms specialize in the same industry but are functionally differentiated; this functional division of labor, to use Emile Durkheim’s [56] classical conceptualization, creates “complementary differences” and thus inter-dependence among these firms, which in turn can foster the emergence of “organic solidarity” within the cluster. The recurrent interactions among firms within the cluster and the long-term relationship that emerges from these can also give rise to network forms of organizations, which have widely been found to enhance economic competitiveness and governance [57].

In comparison, in the diversified clusters we describe here, under normal circumstances, except for businesses providing local services, most economic actors do not have recurrent transactions with each other. Instead, they are separately integrated into different commodity chains, and their transactional partners are located outside the community—in some cases, a long distance away. The spatial clustering in these cases is not formed to serve the diverse economic functions that members of the community now pursue, but is formed as a residential settlement and, in many cases, on the basis of pre-existing social ties such as kinship. Although the division of labor has in fact now risen to a high level in these clusters, as a result of the three processes mentioned earlier, there is little economic inter-dependence among members in normal times. Instead of the organic solidarity based on complimentary differences, to use Durkheim again, members in these socially traditional communities are still primarily connected through mechanical solidarity based on cultural similarities and social familiarity. Table 1 summarizes the key differences between the specialized industrial clusters and the diversified clusters we find in rural China.

Table 1.

A comparison between industrial clusters and diversified clusters.

4. The Research Site and Research Methods

4.1. Case Study: Rationale and the Case Village

A qualitative case study approach was selected in this study. Case study is a distinctive research strategy that takes an in-depth examination of one or more subjects and associated contextual conditions [58,59]. This approach has the notable advantage of providing an understanding of a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context and is well-equipped to answer “how” and “why” questions [59]. The nature of our research question—how diversified clusters are impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and respond to that—requires an in-depth understanding of the impacting process, outcomes, and underlying mechanisms; therefore, a case study approach is appropriate. Our selection of a case was not based on statistical sampling logic, but on the theoretical relevance of the specific case [58,59]. Particularly, a single-case study is useful if the case has critical value in verifying or elaborating theoretical propositions. In this study, we selected a typical case, Norwind Village in northern China, to elaborate our theoretical propositions because the socio-economic features of Norwind cater to our conceptualization of a diversified cluster. The background information on the case is given below.

Norwind is a typical rural village located in western Shandong Province on the North China Plain. It is a medium-scale and moderately wealthy village, with 1292 residents in 423 households and about 133 hectares of collectively owned farmland. Typical of the densely populated North China Plain, land is scarce in Norwind and the scale of family farms miniscule—0.1 ha per capita and and 0.3 ha per household. The prevailing cropping pattern in the North China Plain is also practiced by most of the smallholding family farmers in Norwind: the two main crops of maize in the summer and wheat in the winter supplemented by peanut, soybean, sweet potato, and vegetables. Geographically, the village is well connected to the dense transportation network that spans the North China Plain. A provincial-level motorway passes through the village and connects it to major cities in Shandong Province. The village is also just 4 km away from the center of the town to which it belongs, which has an entrance to a four-lane, tolled highway. The county seat is just 20 km away, and the prefecture-level city—an urban center with a population of 1.3 million—is 30 km away and accessible through multiple routes. All roads within the village are paved and have a hardened surface.

Since the de-collectivization reform in the late 1970s that divided the collective farmland into household plots, economically, residents of Norwind have come a long way from the household-based, smallholding subsistence farming that they had all practiced before. Today, Norwind has become a diversified cluster, typical in the more developed regions of China, thanks to the transformations brought about by livelihood commodification, industrialization, and agrarian transition. Table 2 categorizes households in the village into six types of employment positions.1 As we described when defining diversified clusters, the employment activities of village residents are diversified across economic sectors (industry, commerce, public service, agriculture), organizational forms (wage jobs, self-employment, family business), and spatial scales (local, regional, and long-distance).

Table 2.

Households by employment type in Norwind.

All households in the village have allocated farmland, and the majority continue with farming, but mostly as a source of side income reserved for the elderly in the family. Only a mere 10% of the households—the poorest in the village—rely on that as their main source of income. Another 14% are also primarily farming households, but have specialized into commercial farming households, producing a wide range of agricultural products. Many of them hire wage labor during peak seasons, and some have also rented land to expand their scales—in three cases, by tens of hectares. The majority of households, 54%, are in various forms of wage employment. What differentiates Norwind from villages in the less-developed, labor-exporting, inland regions of China is that more than half of its households are locally employed, a legacy of the successful rural industrialization in this region.

More than one-fifth of the households are in self-employment or run small non-farm businesses. A unique path to business ownership in Norwind is through long-haul trucking, made possible by the village’s easy access to the highway system. The ten largest operators now each own more than 10 semi-trailer trucks (the largest one owns 200), each worth nearly RMB 400,000, and hire two drivers for each truck. Even the smaller operators, who own only one semi-trailer truck, hire two professional drivers for each truck, most of whom are migrants from northeastern China.

Despite the rapid economic changes, socially, Norwind remains a traditional village. More than 300 of the 423 households share the same family name, Feng, but belong to several smaller kinship groups. The smaller lineage group, the Bei, has about 90 households. Only 20 households are more recent settlers and fall outside of the two large lineage groups. Social ties within the village are extensive, and, despite the spread of commercialism and individualism in recent years, the Confucianist traditional cultural norms remain strong.

4.2. Data Collection and Analysis

Case study research uses multiple methods, including semi-structured interviews, participant observation, archives, and even surveys, to collect evidence [59,60]. This study used three data collection methods: semi-structured interviews, a household survey, and secondary data collection. The household economic data on Norwind have been collected over multiple years and are updated regularly. Norwind has been the first author’s research site for many years, and he has collected comprehensive data on all resident households’ economic activities through multiple rounds of surveys and interviews. The data were verified with village reports and key village informants to ensure their accuracy.

For this study on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the first author took a week-long field trip to Norwind in June 2020 and conducted 20 face-to-face semi-structured interviews with a representative sample of the residents. In the following two months, as the situation continued to evolve, he conducted 18 more interviews via telephone and social network apps. The selection of interviewees followed a purposive sampling strategy. Based on the classification of economic profiles of the village households, we selected interviewees from every economic type, and, taken together, the sample of interviewed residents includes representative cases from all six types of households as listed in Table 2. The interviews usually took about 30 min to 1 hour. In each interview, two sets of questions were asked: the first set asked about how their livelihoods and economic activities had been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent lockdown policy; and the second set investigated how they themselves and the whole community coped with the disruptions. Village officials were also interviewed with questions from the two sets of questions but with a focus on the community level and governmental polices on the pandemic. Key informants were repeatedly interviewed to acquire more acute information.

Besides interviews, national and local news reports and policy documents associated with our topic were also collected from multiple sources, including governmental websites and social medial platforms. These secondary data provided information on macro-level policy and structural constraints, which enabled us to triangulate findings from our interview data.

For data analysis, we followed the general process of thematic coding in qualitative research. First, we examined the interview and secondary data repeatedly to become familiar with the materials. Then, we embarked on multiple rounds of manual coding. Coding themes mainly involved the topics closely associated with our research, including (but not limited to): impacts of the pandemic on different social groups; coping strategies of households and the community for the negative impacts imposed by the pandemic; and factors or mechanisms that enabled the coping strategies. The coding process was continuous and iterative, during which analytical memos were recorded as conceptual and theoretical insights sprang up.

As with every research method, the case study approach, or in this study the single-case study approach, has limitations. The generalizability of the conclusions from a single case is a common concern [59,61]. However, the epistemological rationale for the case study approach is not statistical generalization (as large-scale survey-based studies pursue) but analytical or theoretical generalization, namely the external applicability of the theoretical logic generated from the case study [59]. As our conceptualization indicates, the conclusions of this case study only apply to a certain village type (the diversified cluster type) and in a specific situation (a disruptive external shock with lockdown measures and a supply shortage crisis). Beyond that, further research with a new conceptualization is needed. Moreover, the findings from this study do not address the resilience process when communities face slow, long-term transformations such as global climate change. Nonetheless, we believe that our findings have important theoretical relevance in an increasingly risky world characterized by a rising rate of disruptive shocks.

5. The Pandemic: National and Local Responses and Differentiated Impacts

5.1. National and Local Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic

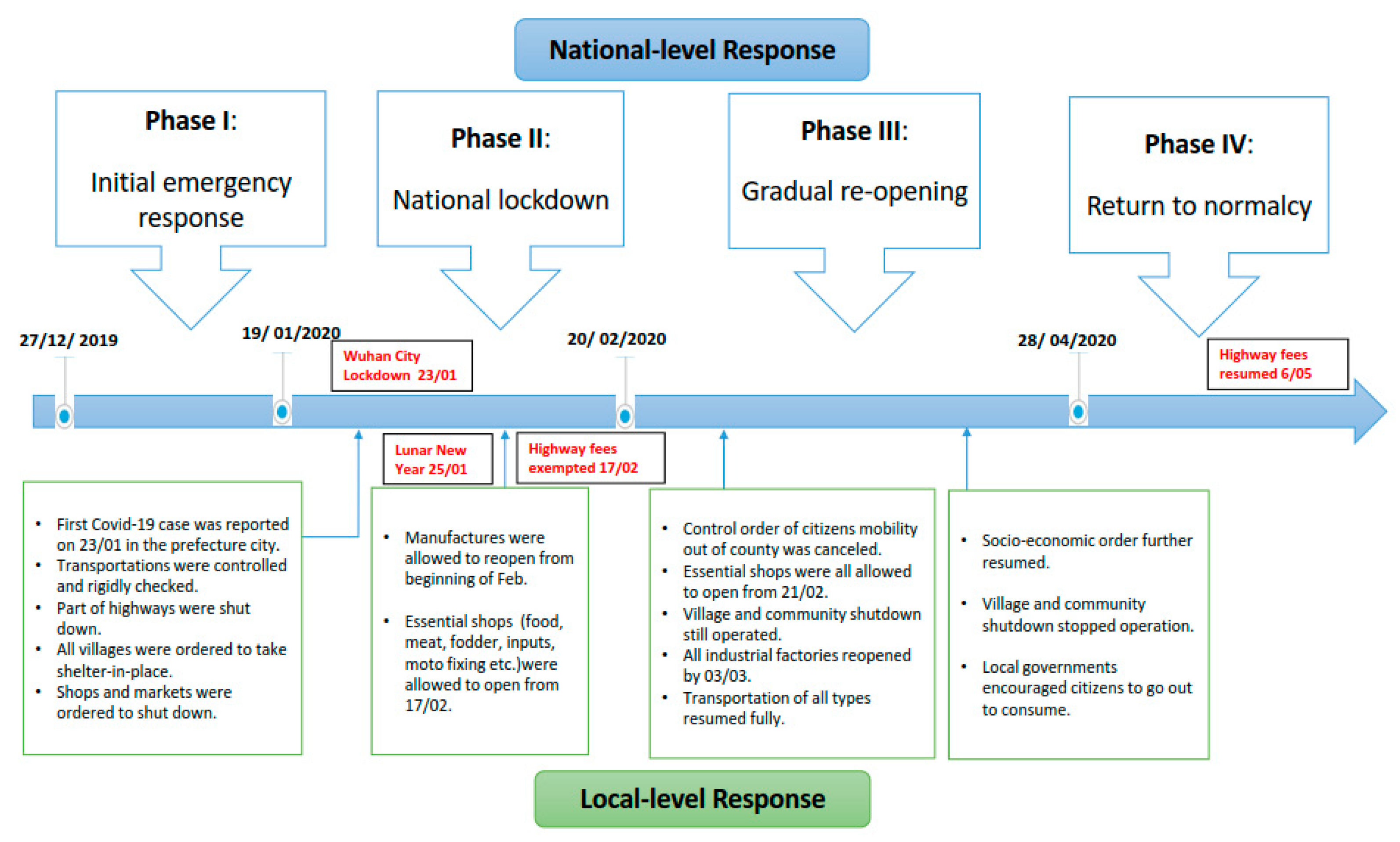

National and regional policies and regulations on COVID-19 set the space of decision-making for social actors, and therefore formed the “policy corridor” for social actions at the community level [62]. The response to the COVID-19 pandemic in China has been a highly dynamic process. We divided the national-level responses to the pandemic into four phases, which are summarized in Figure 1. In Phase I, from the end of December 2019 to 19 January 2020, first the local authorities in the city of Wuhan and Hubei Province, then the central government, grappled with the spread of a new disease caused by a then-unknown pathogen. As the severity of the pandemic became clear, strict quarantine measures began to be implemented in Phase II: first, the lockdown of Wuhan, beginning on 23 January 2020, then various similar measures across the nation. During the one-month period from late January to 20 February 2020, most citizens were ordered to stay at home, economic activities were suspended, and the movement of people and goods was rigidly controlled and reduced to a minimum.

Figure 1.

National and local responses to the COVID-19 pandemic.

These strict measures quickly had the intended effects. After 20 February 2020, when the spread of the disease and the number of cases had been reduced to a manageable level outside of Hubei Province, Phase III began, and the national government scaled down the control measures to start the recovery. On 17 February 2020, the State Council approved the exemption of all highway tolls to speed up the recovery of the transportation system. By 24 February 2020, except for Hubei Province and Beijing city, roads were re-opened and mobility restrictions gradually lifted across the country.

Phase III lasted for two months until 26 April 2020, when the last COVID-19 patient in Wuhan was released from hospital and no new cases had been reported for three weeks. With the disease now effectively contained, Phase IV—the full recovery—began, and the national government shifted gear to re-start the economy and return society to normalcy, while tightly managing sporadic outbreaks of the disease in isolated localities.

Local responses at the prefecture level and the county level, in which Norwind is located, followed the national policies and guidelines. There were roughly two periods in the local responses to the pandemic. First, between 20 January and mid-February 2020, the lockdown period, the most rigid restrictions were implemented: citizens were ordered to stay at home, social gatherings and visitations within villages were discouraged, all commercial activities were suspended, and the movement of goods was tightly controlled and inspected. Half of the highway toll gates were closed to reduce the number of vehicles entering or exiting the highway system. Vehicles distributing essential goods, such as food, livestock feed, and emergency supplies, were allowed to enter villages and other local communities, but all other vehicles from the outside were prohibited.

In Norwind, villagers had spontaneous initial responses to the pandemic before any orders came from the local authorities. Villagers were already well informed of the severity of the pandemic from the media. On 24 January 2020, news spread among villagers through WeChat, the most widely used social media platform in China, that some migrants working in Wuhan had just returned to nearby villages. The next day, which normally would be the busiest day for social activities for the Chinese New Year (CNY), villagers voluntarily practiced social distancing and greatly reduced social interactions. When the official lockdown order came later that day, villagers quickly blocked every road leading into the village and set up checkpoints at all entrances, each guarded by two volunteers.

The lockdown ended in February. In fact, in early February, local governments allowed important manufacturing firms to re-open. From mid-February 2020, commercial shops began to gradually re-open. On 20 February 2020, the prefecture government re-opened all the highway toll gates that had been closed since 30 January 2020, allowing all outside vehicles to enter into local areas. Subject to mandatory temperature taking and upon approval by the village authority, villagers could leave the village to conduct essential activities. Then, around 20 March 2020, all mobility restrictions were lifted and residents could finally move freely; all socio-economic activities returned to normal. Throughout the pandemic, Norwind did not have a single case of infection.

5.2. Differentiated Impacts on the Local Community

In contrast to the severe damages that the COVID-19 pandemic was expected to inflict elsewhere [63], the overall impact of the pandemic on Norwind has mostly been moderate and temporary. Two external conditions contributed to this: first, the fortuitous coincidence of the lockdown with the Chinese New Year holiday; and second, the effective responses by governments at all levels (see [64] for details). None of our interviewees reported having a serious food shortage during the lockdown period, which lasted about three weeks for Norwind. Families had all prepared abundant supplies of wheat flour, the staple in the local diet. The supply of fresh vegetables and fruits became an issue about a week or so into the lockdown; but, as we discuss later, a solution was found.

The greater issue was the economic impact—a delay in or even loss of employment, the suspension of business transactions, and a decline in demand. The economic impact varied across employment positions depending on people’s integration into markets. The least affected were the traditional smallholding family farmers, who are the least integrated into markets. The lockdown happened during the leisure season for wheat farming, and it was only after the re-opening started in February that the wheat fields needed to be fertilized and irrigated. Wheat farmers initially faced a shortage of fertilizers due to the closure of agricultural inputs stores, but local governments soon opened designated retail outlets for agricultural supplies. The price of fertilizer also rose by about RMB 10 per 50 kg, but, given the small scale of these farms, the impact of this increase was insignificant. The wheat harvest this summer was on par with previous years, showing no impact from the pandemic.

In contrast, some of those in specialized commercial farming suffered the greatest losses. The poultry farmers were the worst hit by the lockdown. In normal times, they operated a “just-in-time” supply system, receiving the delivery of chicken feed, which is prone to spoilage, from their suppliers on a daily basis or every other day. Most of them had partnered with a supplier–processor—a meat supplier for fast food chains including KFC and McDonald’s—in the neighboring county. They received the hatchlings and feed from the company and fed the broiler chickens for 30–35 days before delivering them back to the company. They were ill-prepared when the lockdown hit. Mr. Bin recounted his experience:

“We had a very efficient system. If I call my feed supplier tonight, they will deliver it to us the next morning. Chicken feeds are not suitable for long-term storage, as chickens are susceptible to disease, so we need to keep the feeds as fresh as possible. The lockdown after the CNY shut down the supply chain entirely, and we could not get our feeds delivered. I saw thousands of my chickens starved to death. I lost about RMB 20,000 on this”.

Even for those who managed to find feed for their chickens, at the time of maturation (30–35 days), they still could not deliver them to their processor in the neighboring county. Continuing to feed them costed money, and without knowing how long the lockdown would last and whether and at what price the processor would accept them, many chose to just cut the loss, as Mr. Bin did. Some tried to sell the chickens locally, but the local demand was low. We knew of only one farmer, who, after selling his over-grown chickens to the processor in March after the re-opening, was still stuck with 500 unwanted chickens. He eventually had to sell them to locals at a deep discount. Other commercial farmers also suffered losses, although not as severe as the chicken farmers, as they either had longer production durations, were less dependent on commercial input supplies, or managed to sell to local markets.

The wage workers in the village were all delayed in their return to work and thus suffered wage losses. Migrant workers usually return to work one week after the CNY, but this year most could only return after three weeks, in mid-February. Even after returning, they faced a further furlough or wage cut due to the decline in demand. Mr. Gang, for example, who works for a steel company in Tianjin city, told us that the lockdown cost him one-month’s salary; then, after returning to work, his work volume declined by one third, and so did his wage.

In comparison, those who worked locally, for whom spatial mobility was less of a condition on their employment, were far less affected. Most went back to work ten days after the lockdown started, albeit subject to strict body temperature taking and approval from the town government. By our count, by the beginning of February, 12 manufacturing firms in the town had already resumed operations. Mrs. Hua works in an export-oriented axle bearing factory 12 km away from Norwind. Her factory received more orders after the re-opening, and her salary increased. Not surprisingly, according to the village head, about a dozen migrant workers chose to stay home this year, searching for local jobs; most found jobs in local factories. By mid-March, all wage workers—either local or migrant—had returned to work.

The business operators’ experiences during the pandemic were highly divergent across sectors. For long-haul trucking, the mainstay of business ventures in Norwind, the pandemic came as a blessing in disguise. In the past, truck owners had resumed business ten days after the CNY. This year, they had to wait until mid-February, as many local roads were blocked and the highway system was effectively shut down. On 17 February 2020, realizing the need to restore the circulation of commodities and ensure the distribution of food and medical supplies, the national government demanded that local authorities open the highway system and announced the exemption of all highway tolls to spur on the resumption of highway transportation. To long-haul trucking businesses, highway tolls can amount to one third of the operating cost. This exemption, together with the surge in demand after the lockdown, presented a golden opportunity to truck owners in Norwind. In the 80 days until 6 May 2020 when the toll exemption was rescinded, truck owners increased their profits by more than one third, more than making up for the two weeks lost during February.

Other local businesses, such as those selling construction materials, suffered temporary losses, but generally returned to normalcy by the end of March 2020. The worst-hit businesses were the three restaurants in the village. The CNY is the peak season for restaurants, and they had all stocked up on supplies in preparation for the celebratory banquets. As restaurants were only allowed to re-open in late March 2020, they had to give away the foods that they could not consume themselves. One owner estimated to us that he had lost one quarter of his annual revenue.

In summary, the analysis here echoes Rigg and Oven’s [24] finding that market integration of the rural economy in the Global South creates both opportunities and a new form of vulnerability—precarity, with uneven consequences for people located in different market sectors and positions. The highly diversified economic structure in a community such as Norwind thus determines that the blow of any external shock—even one as seemingly all-encompassing as the COVID-19 pandemic—to livelihoods in the community would not be concentrated or cumulative but differentiated and diluted. Furthermore, the spatial disruption caused by the pandemic can have unexpected impacts; a counter-intuitive finding here is that businesses that operated on the largest spatial scale—cross-country, long-haul trucking—fared the best, while those on the smallest spatial scale—village restaurants catering to community members—suffered the most, mostly a result of different policies at the national vs. local level.

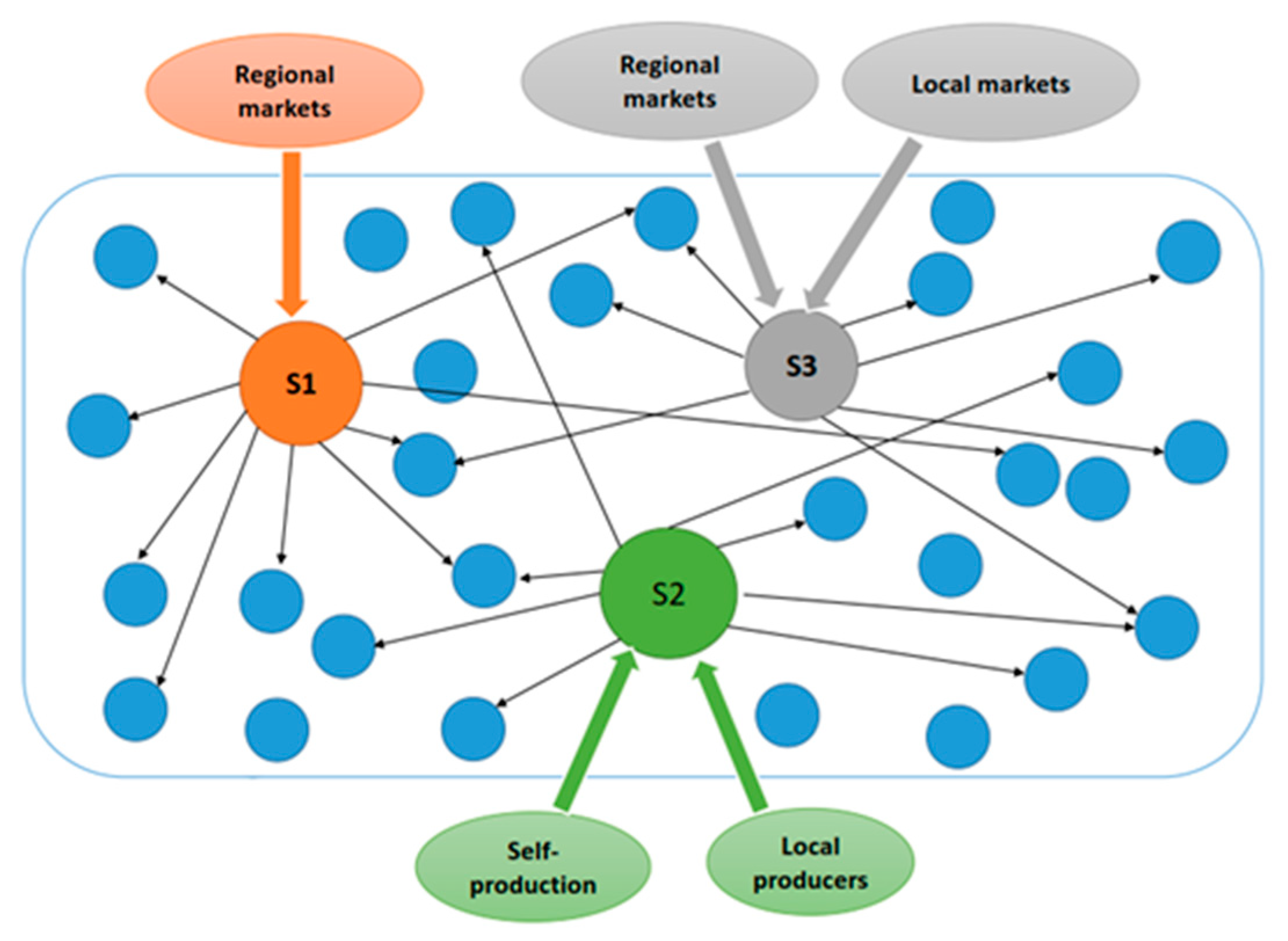

6. Reconfiguring Commodity Chains into Local Commodity Networks

The economic diversification in Norwind not only created structural buffers to cushion the impact of the pandemic as discussed above, but also provided flexibility for community members to actively devise coping strategies to further ameliorate the pandemic’s negative impact. In this section, we use three examples to show how multiple actors re-organized their commodity relationship to address urgent local needs during the lockdown period, illustrated in Figure 2. All three are specialized commodity producers integrated into vertical commodity chains that cross various spatial boundaries. When the lockdown disrupted the spatial connections with external commodity chains, they had to improvise to find new markets for their products. New market relations can only form when there are effective solutions to issues ranging from information exchange to medium of payment, movement of goods, and dispute resolution [65], which, in Norwind’s case, were made possible by the presence of strong techno-physical infrastructure and a healthy stock of social capital.

Figure 2.

An illustration of temporarily reconfigured commodity networks in Norwind village.

Supplier 1, the 30-year-old Mr. Jin, runs a fruit-wholesale business in the prefectural city, supplying fruits to small vendors. He returned to Norwind for the CNY holidays. During and after the lockdown, while unable to continue his business in the city, he built a makeshift market network in the village. Starting in late January, he began to buy oranges in bulk from his supplier in the city and drove his truck to collect and deliver them to Norwind. He and his wife organized an online group in WeChat, which initially consisted of a few relatives and friends, but soon snowballed into 130 members from Norwind and surrounding villages. Once orders were taken from the WeChat group, his wife would then drive her electric tricycle to make deliveries. All payments were made via WeChat as well, mostly upon delivery, in compliance with the “no-contact” regulation. This makeshift network, covering about a quarter of the households in the village, not only maintained the supply of fresh fruits to villagers, but also made the Jins a decent profit: for the two months this had been operating, the couple made an average profit of RMB 200–300 per day, on par with a fully employed laborer’s daily wage.

Supplier 2, Mrs. Guo, operated two large vegetable greenhouses, 0.4 ha in total, growing long beans and cucumbers, and a 0.5 ha apple orchard in the village. Before the pandemic, she had sold most of her vegetables to the wholesale center 30 km away in a neighboring county, a major national hub for vegetable distribution. Mrs. Guo and her father-in-law, who has a 0.2 ha apple orchard, were well known locally for producing high-quality, local-variety apples not available on the wider market. When the lockdown began, villagers started to ask her for apples. She also organized a WeChat group, bringing together her existing customers and social acquaintances, which soon grew to 300 members.

At the beginning, her apples were quickly snatched up by eager customers. For the first 20 days, she was clearing nearly 400 kg of apples per day. She soon added long beans and cucumbers from her own greenhouses when they could be harvested and served as a distribution center for other local vegetable growers, who supplied the cherry tomatoes and mushrooms that they could no longer sell through their normal marketing channels. To collect vegetables from other villages, she asked the growers to put the vegetables at the entrance to their villages, which were still blocked and guarded; she would then use her electric tricycle to pick them up. Her husband continued to work in the greenhouses and orchard, while her mother handled customer service. In a month’s time, this family operation sold 7500 kg of apples (all the stock were sold out), 750 kg of mushrooms, 1000 kg of cherry tomatoes, and 300 kg of cucumbers.

In these two cases, differentially specialized producers re-organized market networks to meet different food needs in the community. In the third example, producers in the same industry, due to their different market positions, also reconfigured commodity networks to adapt to external disturbances.

Supplier 3, Mr. Yang, was the owner of the largest pig farm in Norwind and had taken a different approach to the supply of feed before the pandemic. Instead of buying ready-to-use commercial feeds for all his needs, he would buy concentrated feeds from commercial suppliers in bulk and then mix them with other ingredients such as soybean and corn at his own farm. Before the lockdown, he had stocked up on a sufficient quantity of corn and soybean, all locally grown. When the lockdown started, he continued to receive deliveries of concentrated commercial feeds from his supplier thanks to the large scale of his farm and thus his importance to the supplier. The deliveries would be unloaded on the side of a main road—as foreign vehicles were not allowed to enter villages—that was located near his sister’s house. He would then drive his truck to his sister’s house—five kilometers away from his—to collect the feeds. During the lockdown, leveraging his feed-mixing operation, he became the feed supply center for the other 15 pig farmers in the village.

The three cases above show that when the flow of commodities from outside along the vertical commodity chain was disrupted by the pandemic, the diversified economic structure of the community made it possible for community members to find local substitutes and reconstruct the internal circuits of commodities, which helped to address the challenges faced by both producers and consumers. The well-developed transportation and communication infrastructure, the availability of space-shrinking technologies such as social media, cashless payment, and motorized transportation, and the dense social ties that existed in the community—all of which may not be present in rural areas elsewhere in the Global South—helped to make these temporary commodity networks functional.

7. Discussion and Conclusions

Examining the resilience, particularly the economic resilience, of socio-economic systems on multiple scales is critical to understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic [66,67,68]. Against this backdrop, this study had two research aims: first, to examine the overall impact of COVID-19 upon a typical rural community in China; and second, to examine the resilience of this community in adapting to the abrupt and powerful shock brought about by the pandemic. We describe the deeply market-integrated rural communities, typical in the more developed regions of China, as “diversified clusters”, where labor commodification, livelihood diversification, rural industrialization, and agrarian changes in the past four decades have created a high degree of economic diversity in terms of sectoral specializations, organizational forms, and spatial connections. We found that the economic diversity has provided the community with both structural resilience and processual resilience during the pandemic.

The overall impact of the COVID-19 pandemic upon the economy of Norwind has been relatively modest and temporary. A majority of the households returned to normal economic life after April 2020. The impacts of COVID-19 and its associated control policies have been uneven in the different economic components of the diversified cluster. While the pandemic definitely caused damage to the economy, the economic diversification also led to uneven consequences, creating losers but also relative winners.

In unraveling the coping strategies of local households, we found that villagers successfully created a set of locally based commodity networks. In reconfiguring the commodity networks, the diversified economic structure provided robust resources, including both material and human-related skills and knowledge. The well-established physical and communication infrastructures made market reconstruction efficient. Informal social ties were effectively mobilized to build the commodity network. Mutual trust within the village also generated a certain amount of space for villagers to maneuver during the rigid lockdown. The efficient, flexible, and effective networks successfully satisfied the urgent needs of the community during the most restrictive lockdown period. The sectoral diversity in the local economy provides a resource base that this local commodity network can build upon. This finding urges us to re-evaluate the spatial clustering of economic activities not just in terms of homogeneity and efficiency, but also diversity and flexibility. Therefore, the findings of the case study support our theoretical hypothesis derived from existing studies: Rural communities that are diversified economic clusters and have a healthy stock of social capital will show resilience in the face of disruptions brought about by the pandemic and effectively devise coping strategies to retain basic functions. To be clear, our theoretical argument does not signify a neoliberal understanding and prescription of community resilience [69]. Rather, we show that even in the face of extreme shocks such as the pandemic and rigid lockdowns by the State, communities of the diversified cluster type still have the potential to maintain basic community functions.

This study can shed light on some theoretical discussions related to resilience. First, inspired by industrial cluster theories, we contribute a novel conceptualization of a type of rural community in the Global South and explore its potential for resilience in the face of extreme disruptions brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent rigid lockdown. By highlighting the diversity, flexibility, and social capital in diversified clusters, this study enriches the discussion related to the resilience of rural and economic clusters. Second, this study enriches our understanding of the nuanced connection between market integration and social resilience [24]. Market integration, as the case of Norwind shows, can lead to economic diversification in rural communities, which can contribute to social resilience in disruptive times such as the COVID-19 pandemic. However, on the other hand, deep market integration also differentiates social groups, creating vulnerability and precarity for some and opportunities and wealth for others. In the long run, the rising inequality may erode social cohesion and harm community resilience. Therefore, examination of the role of market integration in social resilience should take dialectical, critical, and dynamic stances and avoid linear, simplistic, and static views.

This study also has practical implications. First of all, as Norwind illustrates, the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic were highly differential across social groups. Supportive policies for rural communities should, therefore, take targeted and differential, instead of indiscriminate, approaches. Moreover, economic diversification is an important attribute of resilient communities that can play critical roles in extreme situations such as the pandemic. Rural development policies that contribute to fostering economic diversification should be emphasized. Lastly, the agency of local communities should be preserved and strengthened in order to help them cope with disruptive shocks. Given that social capital and infrastructures play instrumental roles in the process, policies should strive to advance local social capital and improve rural infrastructures.

In closing, we highlight future directions along this line of inquiry. In this study, we explored community resilience from an economic perspective (in terms of meeting basic functions). Resilience at the community level is, however, multifaceted [70], and social, cultural, and political aspects of community resilience in the COVID-19 pandemic warrant further study. Moreover, our research focuses on the short-term response of local communities to the pandemic, and we found that the cluster showed good resilience in the first phase in addressing a supply shortage. This does not mean that they can perform equally well in addressing a subsequent market decline. The livelihood diversification of households generally happens on a small scale and lacks cooperation across households. This can make rural households extremely vulnerable to the fluctuations in the market in which they are embedded. The seven greenhouse vegetable growers felt tremendous pressure from the vegetable markets, and they may have had to shut down their enterprises if COVID-19 had continued into the following year. Mr. Qiang, Mrs Guo’s husband, said that they had all thought about closing their greenhouses if the situation did not improve. This urges us to think about the temporal dimension of resilience research in general [71]. Short-term impacts and coping processes may differ significantly from long-lasting impacts and coping processes. Therefore, taking a longer timeframe and examining the dynamic changes in local responses to pandemic and post-pandemic challenges may be future research directions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.H. and Q.F.Z.; methodology, Z.H.; formal analysis, Z.H. and Q.F.Z.; data collection, Z.H.; data curation, Z.H.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.H. and Q.F.Z.; writing—review and editing, Z.H. and Q.F.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China, grant number 20CSH020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the interviewees from Norwind Village for their patience and kindness during our data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | When household members are in different job sectors, the main source of income was used to classify the household. |

References

- Foster, J.; Suwandi, I. COVID-19 and Catastrophe Capitalism: Commodity chains and ecological-epidemiological-economic crisis. Mon. Rev. 2020, 72, 545–559. [Google Scholar]

- Volkin, S. How Has COVID-19 Impacted Supply Chains around the World? 2020. Available online: https://hub.jhu.edu/2020/04/06/goker-aydin-global-supply-chain/ (accessed on 25 July 2020).

- Bryceson, F. De-agrarianization and rural employment in Sub-Saharan Africa: A sectoral perspective. World Dev. 1996, 24, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, F. Rural Livelihoods and Diversity in Developing Countries; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, G.; Rigg, J. ‘Post-productivist’ agricultural regimes and the South: Discordant concepts? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2003, 27, 681–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhan, Y.; Fan, S.; Si, W. How China Can Address Threats to Food and Nutrition Security Form the CORONAVIRUS Outbreak. IFPRI Blog. 2020. Available online: https://www.ifpri.org/blog/how-china-can-address-threats-food-and-nutrition-security-coronavirus-outbreak (accessed on 1 June 2020).

- Easters, C. How the COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic Is Impacting Rural America. Forces. 2020. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/claryestes/2020/03/17/coronavirus-and-rural-america/#5c6aa080e108 (accessed on 5 August 2020).

- Phillipson, J.; Gorton, M.; Turner, R.; Shucksmith, M.; Aitcken-McDermott, K.; Areal, F.; Cowie, P.; Hubbard, C.; Maioli, S.; McAreavey, R.; et al. The COVID-19 Pandemic and its implications for rural economies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Xu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Han, H.; Xu, H.; Wang, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, Z. Association between mental health and community support in lockdown communities during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from rural China. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 82, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, S.; Du Toit, A. Adverse incorporation, social exclusion, and chronic poverty. In Chronic Poverty; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013; pp. 134–159. [Google Scholar]

- Rigg, J.; Oven, K.J.; Basyal, G.K.; Lamichhane, R. Between a rock and a hard place: Vulnerability and precarity in rural Nepal. Geoforum 2016, 76, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, I.; McCann, P. Industrial clusters: Complexes, agglomeration and/or social networks? Urban Stud. 2020, 37, 513–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. Clusters and the New Economics of Competition. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, A. Principles of Economics; Macmillan: London, UK, 1890. [Google Scholar]

- Cumbers, A.; MacKinnon, D. (Eds.) Clusters in Urban and Regional Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ceccato, V.; Persson, L. Dynamics of rural areas: An assessment of clusters of employment in Sweden. J. Rural Stud. 2002, 18, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyeon, C.; Byung-Joon, W. Agro-industry cluster development in five transition economies. J. Rural Dev. 2006, 29, 85–199. [Google Scholar]

- Brasier, K.; Goetz, S.; Smith, L.; Ames, M.; Green, J.; Kelsey, T.; Rangarajan, A.; Whitmer, W. Small farm clusters and pathways to rural community sustainability. Community Dev. 2007, 38, 8–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez-Nogales, E. Agro-based clusters in developing countries: Staying competitive in a globalized economy. In Agricultural Management, Marketing and Finance Occasional Paper; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Thanh, L.; Nhat, L.; Dang, H.; Ho, T.; Lebailly, P. One village one product (OVOP)—A rural development strategy and the early adaption in Vietnam, the case of Quang Ninh Province. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Natsuda, K.; Igusa, K.; Wiboonpongse, A.; Thoburn, J. One Village One Product—rural development strategy in Asia: The case of OTOP in Thailand. Can. J. Dev. Stud. 2012, 33, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N. One village, one product: Agro-industrial village corporatism in contemporary China. J. Agrar. Chang. 2018, 18, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G. Multifunctional Agriculture: A Transition Theory Perspective; CABI: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rigg, J.; Oven, K. Building liberal resilience? A critical review from developing rural Asia. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 32, 175–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marsden, T. Towards the political economy of pluriactivity. J. Rural Stud. 1990, 6, 375–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggblade, S.; Hazell, P.; Reardon, T. The rural non-farm economy: Prospects for growth and poverty reduction. World Dev. 2010, 38, 1429–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loison, S. Rural livelihood diversification in Sub-Saharan Africa: A literature review. J. Dev. Stud. 2015, 51, 1125–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rigg, J.; Salamanca, A.; Parnwell, M. Joining the dots of agrarian change in Asia: A 25 year view from Thailand. World Dev. 2012, 40, 1469–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.F.; Donaldson, J.A. From peasants to farmers: Peasant differentiation, labor regimes, and land-rights institutions in China’s agrarian transition. Politics Soc. 2010, 38, 458–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackinnon, D.; Derickson, K.D. From resilience to resourcefulness: A critique of resilience policy and activism. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2013, 37, 253–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, C.A. Community resilience and contemporary agri-ecological systems: Reconnecting people and food, and people with people. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2008, 25, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G. Community resilience, globalization, and transitional pathways of decision-making. Geoforum 2012, 43, 1218–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.A.; Hu, Z.; Rahman, S. The resilience of Chinese rural communities: The case of Hu village, Sichuan Province. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 60, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adger, W. Social and ecological resilience: Are they related? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2000, 24, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.; Emrich, C.; Mitchell, J.; Boruff, B.; Gall, M.; Schmidtlein, M. The long road home: Race, class, and recovery from Hurricane Katrina. Environment 2006, 48, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclean, K.; Cuthill, M.; Ross, H. Six attributes of social resilience. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2014, 57, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öz, Ö.; Özkaracalar, K. What accounts for the resilience and vulnerability of clusters? The case of Istanbul’s film industry. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2011, 19, 361–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, D.; Meyer, M. Social capital and community resilience. Am. Behav. Sci. 2015, 59, 254–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, G.; Carson, D. Resilient communities: Transitions, pathways and resourcefulness. Geogr. J. 2015, 182, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z. Deagrarianization and Depeasantization: A Dynamic Process of Transformation in Rural China. Rural China 2021, 18, 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics. Statistical Report of 2019 National Economic and Social Development of China. 2020. Available online: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202002/t20200228_1728913.html (accessed on 6 August 2020).

- Murphy, R. How Migrant Labor Is Changing Rural China; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, J.; Wang, Y.; Long, N. Farmer initiatives and livelihood diversification: From the collective to a market economy in rural China. J. Agrar. Chang. 2009, 9, 175–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Rahman, S. Economic drivers of contemporary smallholder agriculture in a transitional economy: A case study of Hu Village from southwest China. Singap. J. Trop. Geogr. 2015, 36, 324–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Byrd, W.A.; Lin, C.S.; Lin, Q. (Eds.) China’s Rural Industry: Structure, Development, and Reform; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Christerson, B.; Lever-Tracy, C. The third China? Emerging industrial districts in rural China. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 1997, 21, 569–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigg, J.; Salamanca, A.; Thompson, E.C. The puzzle of East and Southeast Asia’s persistent smallholder. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 43, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blecher, M.J.; Shue, V. Tethered Deer: Government and Economy in a Chinese County; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Li, E.; Coates, K.; Li, X.; Ye, X.; Leipnik, M. Analyzing agricultural agglomeration in China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ministry of Agriculture. Reply to the No. 3421 Advice from the Fifth Session of the Second National Congress Conference. 2017. Available online: http://jiuban.moa.gov.cn/sjzz/jgs/cfc/zcfg/bmgz/201710/t20171018_5843015.htm (accessed on 5 August 2020).

- Zhang, Q.F. Comparing Local Models of Agrarian Transition in China. Rural China 2013, 10, 5–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, H. Class Dynamics of Agrarian Change; Kumarian Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, H.; Chen, Y. Agrarian capitalization without capitalism? Capitalist dynamics from above and below in China. J. Agrar. Chang. 2015, 15, 366–391. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.F. Class Differentiation in Rural China: Dynamics of Accumulation, Commodification and State Intervention. J. Agrar. Chang. 2015, 15, 338–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.F.; Zeng, H. Politically directed accumulation in rural China: The making of the agrarian capitalist class and the new agrarian question of capital. J. Agrar. Chang. 2021, 21, 677–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, É. The Division of Labour in Society; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Podolny, J.M.; Page, K.L. Network forms of organization. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1998, 24, 57–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Axsen, J.; Sorrell, S. Promoting novelty, rigor, and style in energy social science: Towards codes of practice for appropriate methods and research design. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2018, 45, 12–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerring, J. What is a case study and what is it good for? Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2004, 98, 341–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilson, G. Community resilience, policy corridors and policy challenge. Land Use Policy 2013, 31, 298–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Our Hungriest, Most Vulnerable Communities Face “a Crisis within a Crisis”. 2020. Available online: http://www.fao.org/news/story/en/item/1269721/icode/ (accessed on 1 August 2020).

- Zhang, Q.F.; Hu, Z. Rural China under the COVID-19 pandemic: Differentiated impacts, rural-urban inequality, and agro-industrialization. J. Agrar. Chang. 2021, 21, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fligstein, N. Markets as Politics: A Political-Cultural Approach to Market Institutions. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1996, 61, 656–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewett, R.L.; Mah, S.M.; Howell, N.; Larsen, M.M. Social cohesion and community resilience during COVID-19 and pandemics: A rapid scoping review to inform the United Nations research roadmap for COVID-19 recovery. Int. J. Health Serv. 2021, 51, 325–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, D.J. Community susceptibility and resiliency to COVID-19 across the rural-urban continuum in the United States. J. Rural Health 2020, 36, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yip, W.; Ge, L.; Ho, A.H.Y.; Heng, B.H.; Tan, W.S. Building community resilience beyond COVID-19: The Singapore way. Lancet Reg. Health West. Pac. 2021, 7, 100091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, J. Resilience as embedded neoliberalism: A governmentality approach. Resilience 2013, 1, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, G.A. Community resilience: Path dependency, lock-in effects and transitional ruptures. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2014, 57, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L. Resilience to what? Resilience for whom? Geogr. J. 2016, 182, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).