Abstract

It has been persuasively argued that relationship networks affect the socio-economic behaviors of actors. However, few studies have recognized the location and context of actors in relationship network. To address this challenge, this paper examined the skill learning and chain migration which were affected by relationship network within spatial situation, by using data covering 115 households in the specialized village of fried dough sticks (youtiao). The results showed learning from neighbors with geographical closeness played an important role in expanding the space and enhancing efficiency of skill learning. It could be noted that the establishment of master-prentice relationship networks was related to the spatial proximity of farmers’ dwellings, and constrained by the space of villagers’ group. Farmers’ chain migration showed the closer the spatial distance of farmers, the nearer the migration destination they choose. Farmers’ livelihoods were constrained by the differences of spatial contexts. Farmers with smaller amounts of cultivated land were more likely to flow into cities with long distance for selling fried dough sticks, and they usually became fixed merchants. In contrast, farmers with more cultivated land were more likely to migrate to the countryside with short distance and usually became mobile vendors. It should better understand the socio-economic behaviors and the change of regional livelihoods, if we will focus on relationship networks embedded in spatial situation in future research.

1. Introduction

The individual’s life course exists in different locations. In addition, this “spatiality” lays the foundation for individually-differentiated learning opportunities and experiences. However, people do not take socio-economic behaviors in isolation. This is because individuals are accustomed to acquiring information from acquaintances in the course of their daily communications. In addition, their actions are often embedded in the surrounding relationship network and constrained by spatial context.

1.1. Socio-Economic Behaviors Associated Relationship Network

The concept of “relationship network” was first derived from Barnes, a British sociologist, and used by Fisher, Wellman and other sociologists in urban social research earlier. Later, Granovetter creatively used this concept to examine the relationship embeddedness of career transformation. He believed that each person is not a complete rational-economic individual. Since people usually obtain reliable, detailed and available information from acquaintances [1]. It means that people’s economic behaviors are embedded in predictable and trusted social relationships [2]. Therefore, the analysis of persons’ information acquisition, mobility behavior and career choice are meaningful on basis of relationship network. Relationship network affects the people relate to each other, organize themselves and interact which plays an important role in rural development [3]. Farmers prefer to acquire information and support from other farmers who are from a certain geographical and social proximity [4]. These shared information among farmers influence individual behavior. For example, some researchers have argued neighbor effect determine the adoption of conservation tillage by farmers [5]. Sociability, social cohesion and trust among farmers are helpful to improve their social capital, which facilitates access to technology [6]. Thus, the quality and diversity of relationship network is important for farmers’ decision-making [7]. The farmers with an emotion closeness and a broader network are more likely to facilitate knowledge and skills acquisition [8].

Individual farmer’s socio-economic behaviors embedded in the relationship network is related to group decision-making. It conveys the social connectivity and trust. Thus, relationship network provides a general methodology for understanding the social structure and socio-economic behaviors [9]. Several studies have shown spatial clustering of individuals who are connected because of the share of job resources and the support from acquaintances [10,11]. For example, the analysis of census data in the United States has shown that increasing more new immigrants follow their compatriots. Moreover, they engage in the same occupation in the same city as their compatriots [12]. In Europe, the behavior of immigrants has also deviated from the hypothesis of the “rational-economic man”. Once settled in the migration destination, the type of jobs that they engage in has largely depended on relatives and ethnic networks [13]. In Singapore, Chinese people used their countrymen relationship to acquire skills and seek employment opportunities, which allowed Chinese farmers to settle in foreign countries [14]. In China, both comprehensive official statistics (Rural-Urban Migration in China, RUMiC) and long-term micro-case surveys have revealed that the vast majority of Chinese farmers regard kinships and geographic relationships as important informal channels when they migrate [15,16].

1.2. The Principles and Practices of Chinese Farmers’ Behaviors

China is a typical acquaintance-based society, where people focus on kinship and neighborhood. Chinese social relationships are similar to ripples caused by stones thrown into the water. The ripples extend and project outward in a circular fashion. While the inner circle represents families and close relatives, the outer circles can be linked to relationships between the individual and others, which become increasing more and more distant. This means that the social relationships that occur within themselves appear to be different [17]. Relationship network among farmers is argued to shape rural livelihoods [18]. Under the conditions of small-scale production in China, agricultural income is limited, and the gap between urban and rural residents is becoming wider and wider. A growing number of Chinese farmers are no longer entirely reliant on land to sustain their livelihoods. Non-agricultural forms of employment are often needed to maintain or improve their income [11]. Capable person with initial capital outlay, technology, information or practical experience often become core figures and engage in the new livelihoods early [19]. Relying on close kinship and neighborhood, more and more farmers in the village engage in the new economic activities with the help of capable person [20,21]. Consequently, most of the learning process takes place in a certain spatial proximity [22]. For example, “Taobao village” is growing day by day, and its main industry is e-commerce. People have the entered e-commerce industry, express industry, advertising industry and other related industries as the result of driving role of their relatives and other villagers [23]. The number of local online stores has seen explosive growth [24]. This shows that individual behaviors stimulate the social vitality originally bound to the land, and lead to the formation of group actions through social relationship networks.

In the process of China’s industrialization, the rural floating population undertake a lot of heavy or repetitive work, which have profoundly promoted the change of urban and rural areas. They are accustomed to obtaining relevant information and support from persons who have already migrated through their relationship networks during migration process. Kinship and neighborhood relationship among floating farmers are important factors affecting chain migration. For example, many practitioners in wholesale markets in Guangzhou came from Chaoshan city in the northeast of Guangdong Province. Through relationship, they have shared the news with the villagers and provided opportunities and support to relatives and friends who wish to work and study [25]. More typically, under the influence of fellow townsmen relationship, the solidarity economy, based on “fellow townsmen in the same industry”, has become widespread in China. This refers to people from the same area who rely on rural social relationship networks to engage in the same industry outside of the countryside [26]. Examples include the copying industry in Xinhua in Hunan Province, the “Lanzhou Stretched Noodles” industry in Hualong in Qinghai Province and the steamed stuffed bun industry in Jianli in Hubei Province.

1.3. Relationship Network within Spatial Situation

It is worth noting that social relationship and spatial relationship are not separate, but in dialectical unity. Considering the emphasis placed on “spatial turn” in social theory, researchers began to criticize thought forms that separated society from the space, and instead advocated the dialectical unity of these two elements. That is, “where there is space, there are social relationships” [27]. Since every individual holds their own location, their face-to-face contacts and social interactions will present the corresponding geographical space [28]. So, we argue that analyzing socio-economic behaviors require a solid understanding of the location and context in which actors within relationship networks weave. Spatial situations include not only the objective location and distance of actors, but also the spatial context of relationship network.

On the one hand, it is well understood the connections and communications between individuals shaped by location and distance. Both social and geographical proximity can diminish the communication costs and enhance the efficiency of mutual learning [29,30]. Many early research examining networks focused on the influence of distance in relationship formation. It was shown that ties between individuals were related to the spatial proximity of dwellings [31]. When researchers analyzed the relationship network of village residents in central China, they found that it was difficult to spread information effectively due to the large-scale of the administrative villages [32]. Despite communication technology makes it easier for people to communicate, relationship is often formed with those in closer proximity [33]. On the other hand, we should be aware of embeddedness is not equate to localness [2]. The spatial context is different in different places which shape or restrict persons’ different choices. For example, farmers from different villages had different choice of migration destinations [34]. Sectoral contexts shape the actor-producer relationship. In artisan food firms, informal networks such as business networks, family associations play a more important role in innovation than institutional networks. [35]. So, the spatial situation model provides a new entry point for research on relational networks. It is possible to explore organizational relationships within the actors, as well as the restrictive impact of geographical contexts on personal or collective actions [36].

Based on the existing studies, it is helpful for us to understand farmers’ socio-economic behaviors in relationship networks. The tightness, type and structure of the relationship network emphasized widely in research. However, few studies are aware of the “location” and “context” characteristics which actors cannot eliminate. Moreover, few researchers think about the formation and diffusion of farmers’ economic behaviors from this perspective. Spatiality has become an important dimension to reveal the social relations behind socio-economic behaviors. Thus, we considered relationship network, actors’ location and spatial context simultaneously. We must recognize how location and distance affect farmers’ skill learning of fried dough sticks and chain migration. In addition, what spatial context affect the skill diffusion and migration mode. The overall objective in this paper is to gain a better understanding of how relationship networks within spatial situations shape the farmers’ behaviors of skill learning and chain migration. It can be realized by answering the following questions: (1) How does proximity influence famers’ behaviors? (2) What are the characteristics of skill learning and chain migration depending on relationship networks within spatial situations? (3) What are the differences in the mode of migration was restricted by the spatial contexts?

The paper proceeded by exploring the farmers’ behaviors of skill learning and chain migration in the specialized village of fried dough sticks in Dengcheng Town, stressing the spatial constraints behind famers’ behaviors. Firstly, we provided a brief relevant literature, then described the study area and data collection process, followed by explaining the methods used in this paper. A case study revealed rich details of the process and geographical space of skill learning and chain migration. The paper concluded with a discussion of the theoretical and practical value of spatial situation and the conclusions based our findings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

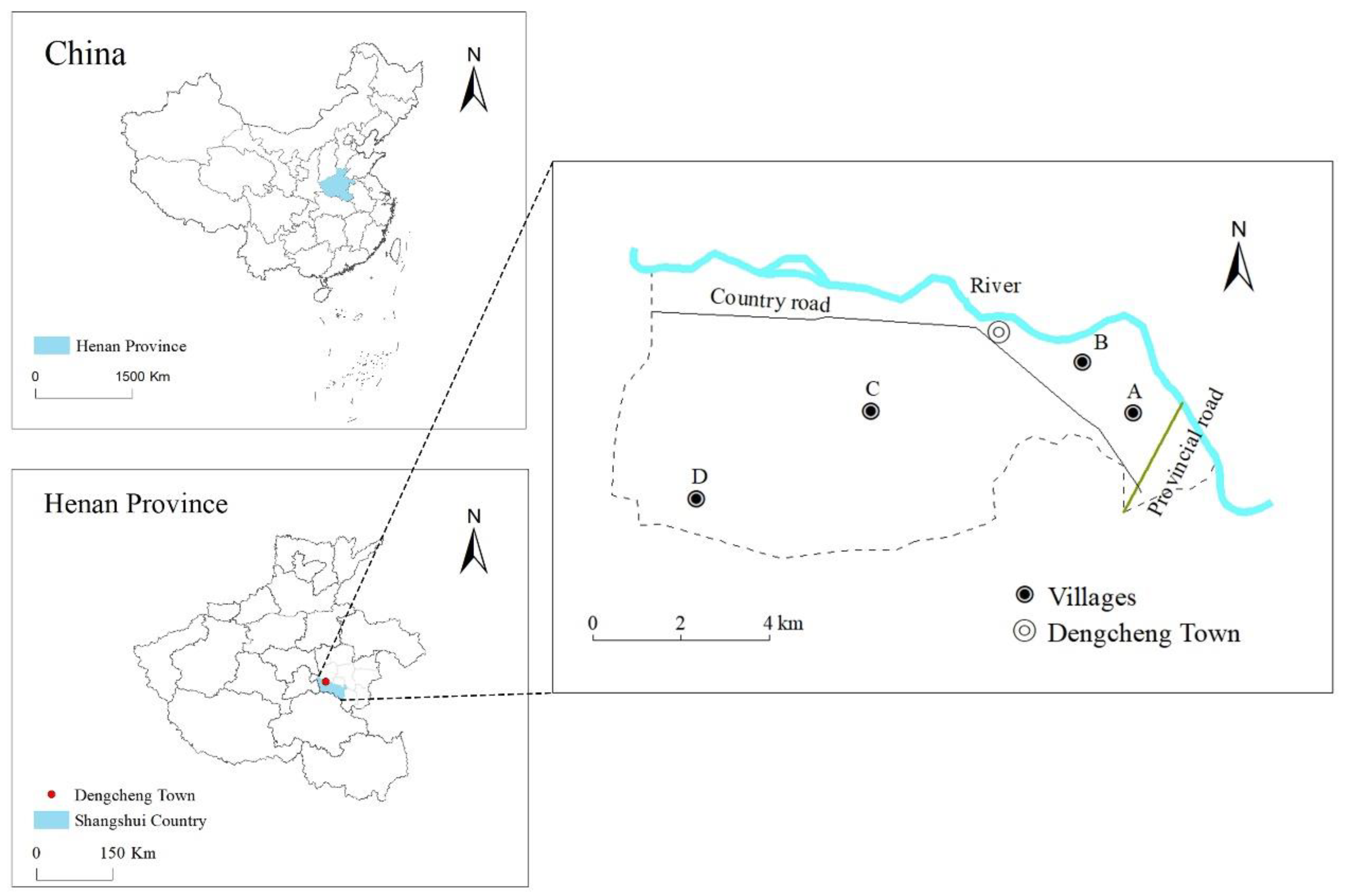

Fried dough sticks (youtiao) are a traditional Chinese pastry. They consist of long strips that are crispy on the outside and soft on the inside. Dengcheng Town is located in Shangshui County, Zhoukou City, Henan Province in central China (Figure 1). It is known as the “hometown of fried dough sticks in the Central Plains”. It is similar with many villages in China, most farmers engage in non-agricultural livelihoods during the slack season. In this town, almost one third of the population sells fried dough sticks in different parts of the country. Xiaoyao Town, which is adjacent to Dengcheng Town in the north, is famous for “soup with pepper”. The shops of soup with pepper are widely distributed in various cities. “Soup with pepper” with “fried dough sticks” is a favorite breakfast of many Chinese citizens.

Figure 1.

Location of the Study area.

It is representative to research the farmers who operate fried dough sticks business. First, the relationship network is clear and traceable. Making fried dough sticks is a skill that must be learned from skilled persons. Farmers often long for skilled persons to teach them the skill of making fried dough sticks. From the perspective of the skilled person, it usually takes about 1 year to teach a prentice the skill of making fried dough sticks. As such, they usually prefer to choose people with whom they have a familiar relationship as prentices. The relation of master and prentice is an important relationship network. Second, there are obvious differences in migration modes and destinations. Famers living in the east of the Dengcheng Town sell fried dough sticks in cities. Famers living in the middle or west of the town sell fried dough sticks in the countryside. Focusing on the theme that farmers’ socio-economic behaviors depend on relationship networks, with the help of typical case and spatial situations, this paper analyzed the spatial constraints of skill diffusion and migration mode.

2.2. Data Processing

In the 1980s and 1990s, the skill of making fried dough sticks in Dengcheng Town rose. At that time, the income from fried dough sticks was dozens of times higher than that earned from agricultural work. More and more famers begun to learn the skill, they also relocated to other places throughout the year or seasonally to use their skills to procure income. From 1 January 2018 to 12 January 2018, we carried out a comprehensive survey and inquiry in the villages that make up the whole town. We made it clear that Village A (Lamei Village), located in the east of the town, was the first village that made fried dough sticks. We also established contact with the master who first learned the skill of making fried dough sticks. From 11 February 2018 to 16 February 2018, we verified the operations of all the farmers in Village A and conducted questionnaires and interviews with famers selling fried dough sticks, clarified the relationship networks of master and prentice. The questionnaire and interview were involved the earliest time of selling fried dough sticks, the location of selling fried dough sticks, the reasons for changing the location of selling fried dough sticks, how to obtain information and support, whether learn skills from neighbors or relatives, whether to teach the skills to others, the occupation before selling fried dough sticks, and so on. We assigned a number to all of the farmers and marked the number on their houses on the satellite map.

In addition, we found that most of the farmers in the eastern villages migrated to cities and were fixed merchants. The farmers in the western villages basically moved to the countryside and were mobile vendors. To make a better comparative study, from January to February 2020, we also conducted questionnaires and interviews with famers selling fried dough sticks in Village B (Xu Village), Village C (Wangzhuang Village) and Village D (Xiyingzi Village) from east to west (Figure 1). Moreover, we obtained relevant socio-economic data related to the four villages from the local official statistics report. We interviewed all the households in the four villages, the number was 666. It included 238 households engaged in fried dough sticks, we conducted questionnaires with all of them. In addition, we eliminated households with discontinuity of making fried dough sticks and incomplete of information, as well as households who were unwilling to disclose information. In total, we collected information from 115 households covering four villages, and conducted in-depth interviews with 35 households, which lasted approximately 40 min.

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Social Atlas

Usually, in the form of a map, we can describe and compare the patterns of relationship networks, analyze the modes and conditions of different relationships. Unfortunately, most studies do not include the micro location of the actors involved. Some scholars have noticed that if ArcGIS technology can be used to visualize the location of actors in relationship networks, it will help to further explore the spatiotemporal characteristics and mechanism of relationship networks [37]. Some other researchers have also proposed that the original nonspatial entities can be analyzed by stacking information on the locations using spatial methods [38]. Since relationship networks are composed of a series of actors, we can integrate the location with the social attributes of the actors involved for expression [39]. Since different elements require the use of different map methods, we need to select an appropriate map method to represent the relationship networks [40]. In this paper, we used ArcGIS to visualize the location of farmers with the skill of making fried dough sticks with point symbols. The locations of the master and prentice are represented by different types of point and are connected by lines to express their social relationships. Then the data covering the time of making fried dough sticks, the way of learning skills and the location of migration were stacked to the corresponding locations. Followed kernel density estimation was performed. Finally superimposed the results with spatial maps.

2.3.2. Kernel Density Estimation

Kernel density estimation is a non-parametric method, which can effectively visualize the distribution pattern of point elements at given location [41]. The calculation formula is:

Here, f (x, y) is the density value of the location (x, y); h is the kernel bandwidth; n is the number of the estimated geographical elements; k is the density function; di, (x, y) is the distance between the location i and the location (x, y). In this paper, kernel density estimation was used to analyze the spatial distribution of years of making fried dough sticks and migration destinations.

3. Results

3.1. Within Resident Situations

3.1.1. Skill Learning Efficiency

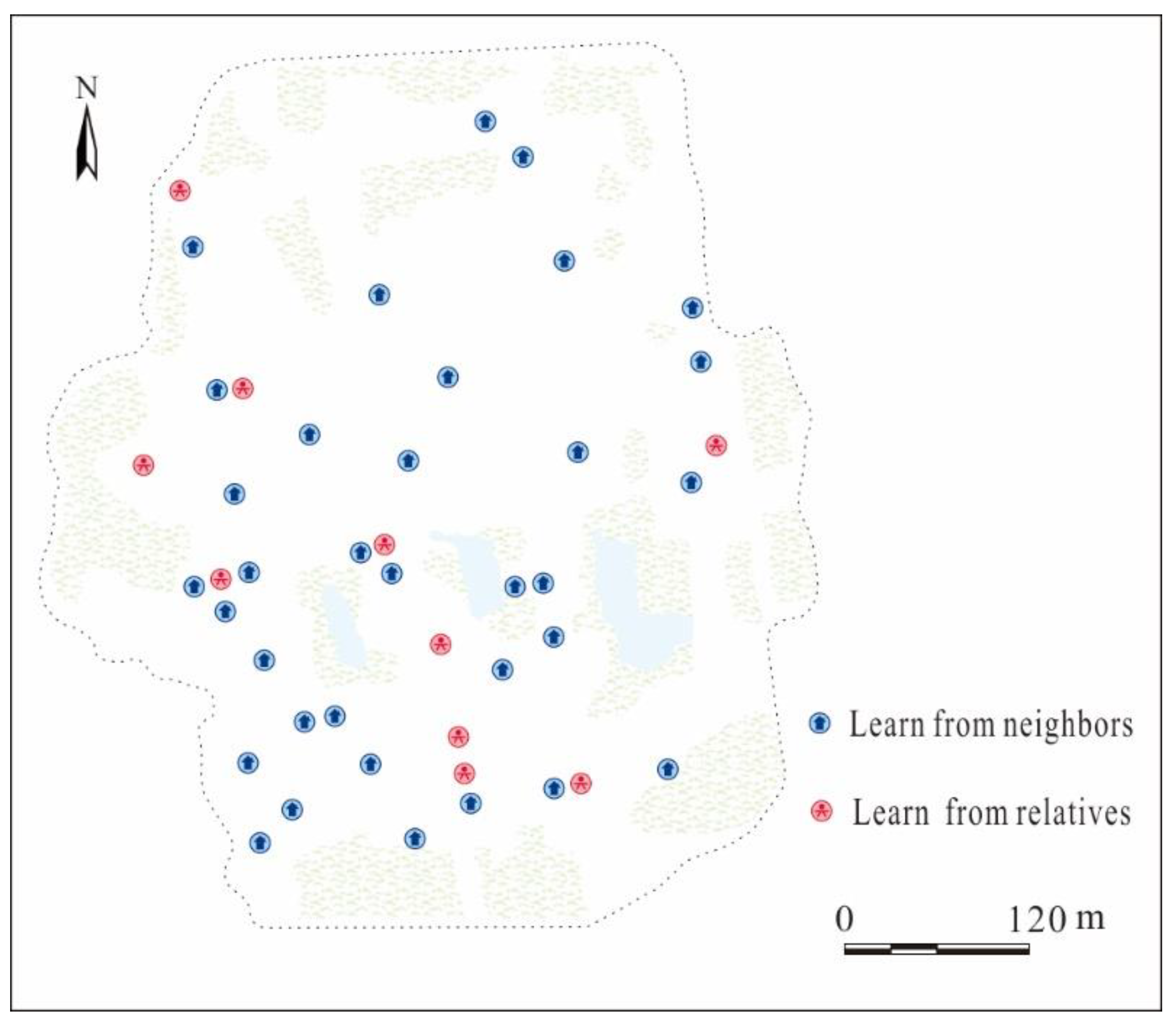

By comparing skill learning in respect to making fried dough sticks in the four villages, we found that the proportion of making fried dough sticks of farmers in Village A, Village B, Village C and Village D was 41.7%, 34.2%, 47.6% and 14.5%, respectively. In terms of management years, the number of years spent selling fried dough sticks in Village A, Village B, Village C and Village D was 26.5 years, 21.5 years, 25.2 years and 20.6 years, respectively. Obviously, the skill learning efficiency in Village A and Village C is better than that in Village B and Village D. This because in Village A and Village C, 73.9% and 52% of the farmers, respectively, learned the skill from their own villagers, whereas 12.9% and 7.7% of the farmers in Village B and Village D, respectively, learned this skill through their own villagers. Learning from neighbors with geographical closeness enhance the efficiency of skill learning. Farmers were able to timely establish relationship with neighbors within a certain spatial proximity. To further confirm this point, we visualized two skill learning approaches of farmers in Village A: learning from neighbors and learning from relatives (Figure 2). It showed that the spatial distribution of learning from neighbors was wider than that of learning from relatives. In Village A, most famers learned skills from their neighbors, indicating neighborhood relationships played an important role in expanding the space of skill learning.

Figure 2.

Learning approaches of farmers in Village A.

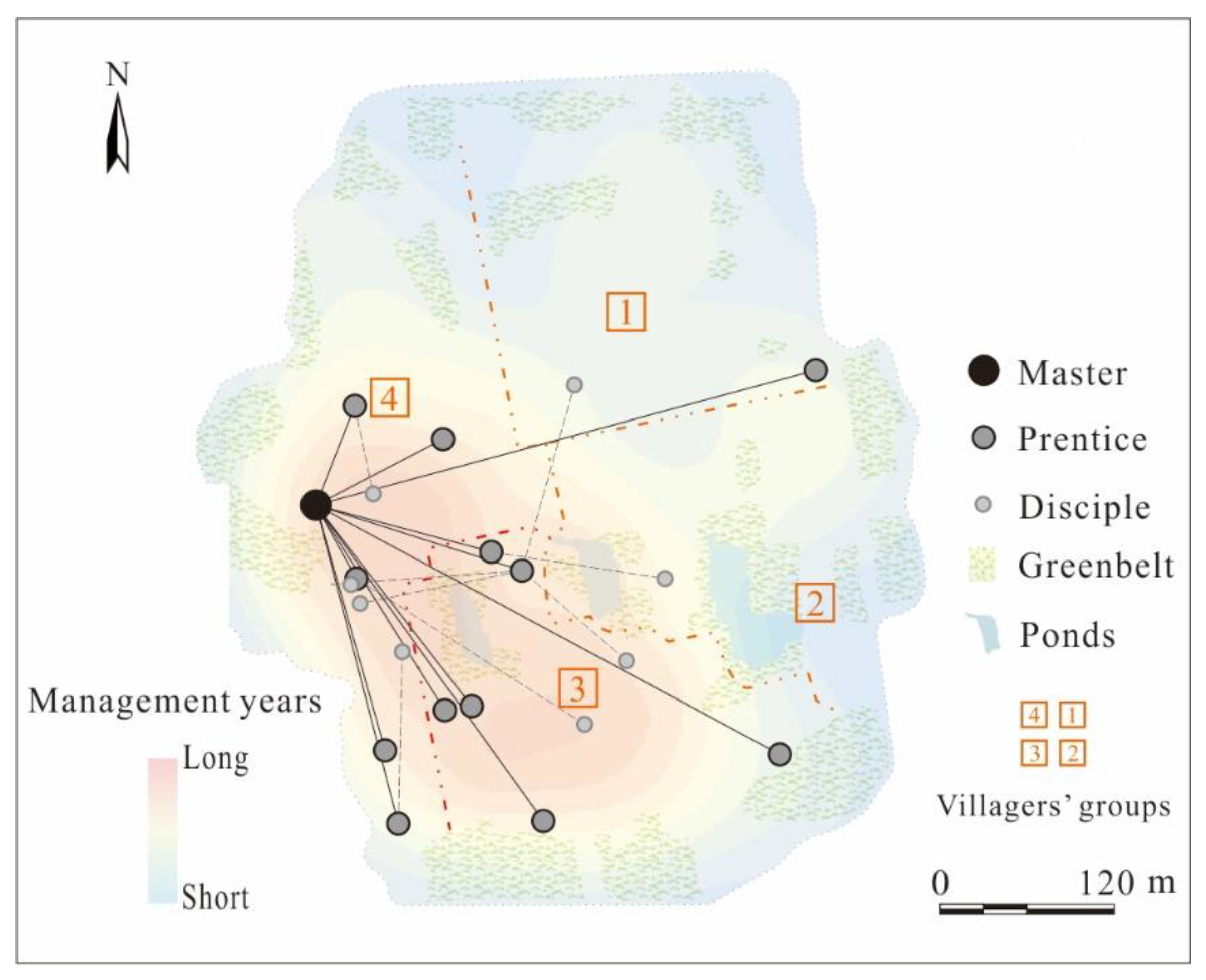

3.1.2. Skill Diffusion Boundary

The distance affects the establishment of the relationship networks among actors. Consequently, it well understands that skill learning always take place within a certain spatial proximity. To further confirm this point, we visualized the location of the master and prentices in Village A and conducted kernel density estimation on the number of years spent selling fried dough sticks (Figure 3). As can be seen from Figure 3, master-prentice relationship networks were mainly concentrated in the third and fourth villagers’ group. In addition, skill learning in respect to making fried dough sticks mainly occurred in the third and fourth villages’ group. The master once lived in the third villagers’ group and later moved to the fourth villagers’ group. His prentices basically lived in the third and fourth villagers’ group. The master had only one prentice of the same age in the first villagers’ group. Moreover, the disciples were still mainly limited to the original villagers’ groups. The number of years spent selling fried dough sticks was also longer in the third and fourth villagers’ group than that of the first and second villagers’ group. The spatial distribution of the number of years spent selling fried dough sticks was highly consistent with the distribution of the master-prentice relationship chains. In Chinese villages, the establishment of groups of villagers to facilitate management and daily production work has played an essential role in uniting neighbors. The capable person in Village A remarked, “My neighbor’s living conditions were poor. I saw that my neighbor’s child is very smart. I taught him the skill of making fried dough sticks. Later, I gave him some capital to start a business outside. He made money in the same year. Later, although the prentice had children, he often came to give me some gifts. I told him that none of you need to give me gifts in the future. I feel very proud and happy in my heart. People need to do more good things”.

Figure 3.

The main networks of skill learning in Village A.

3.2. Within Migration Situations

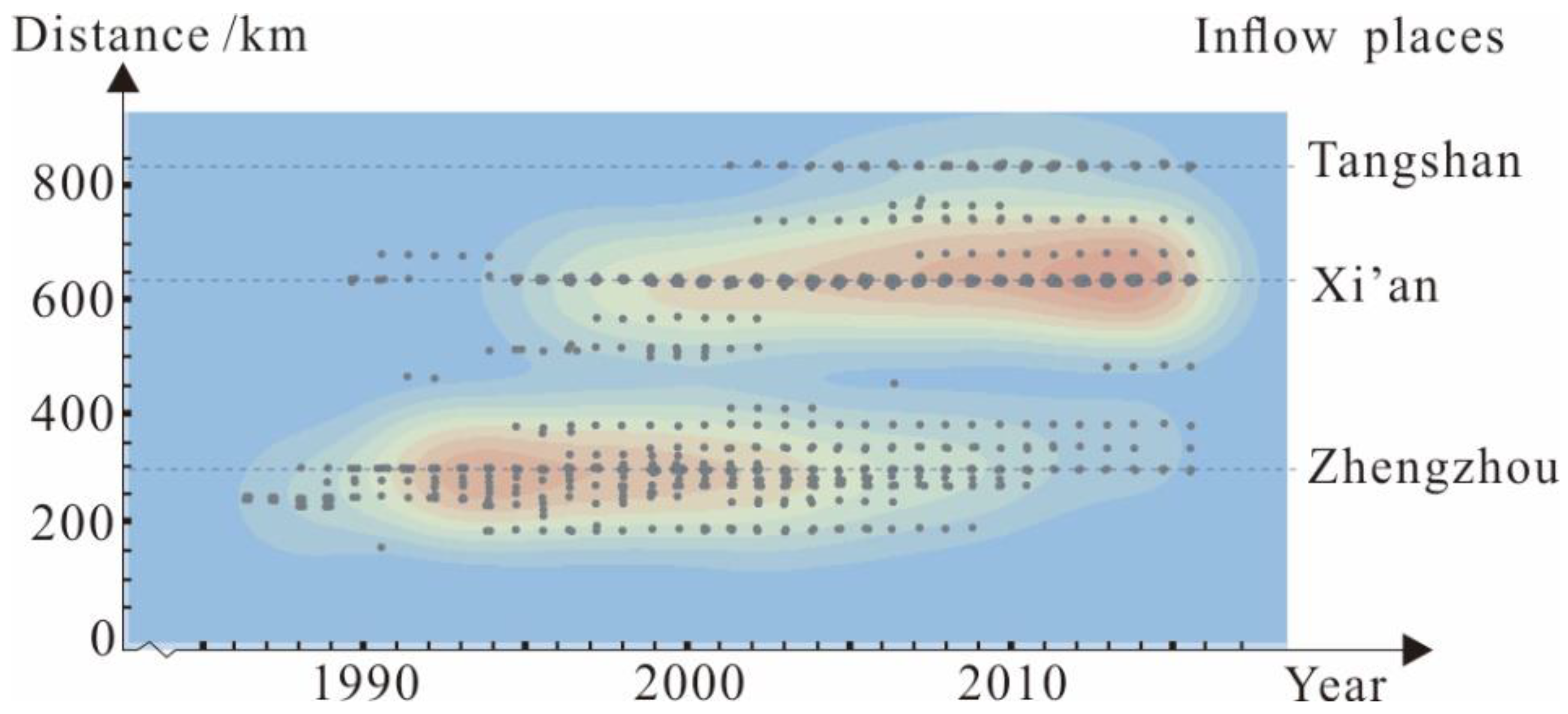

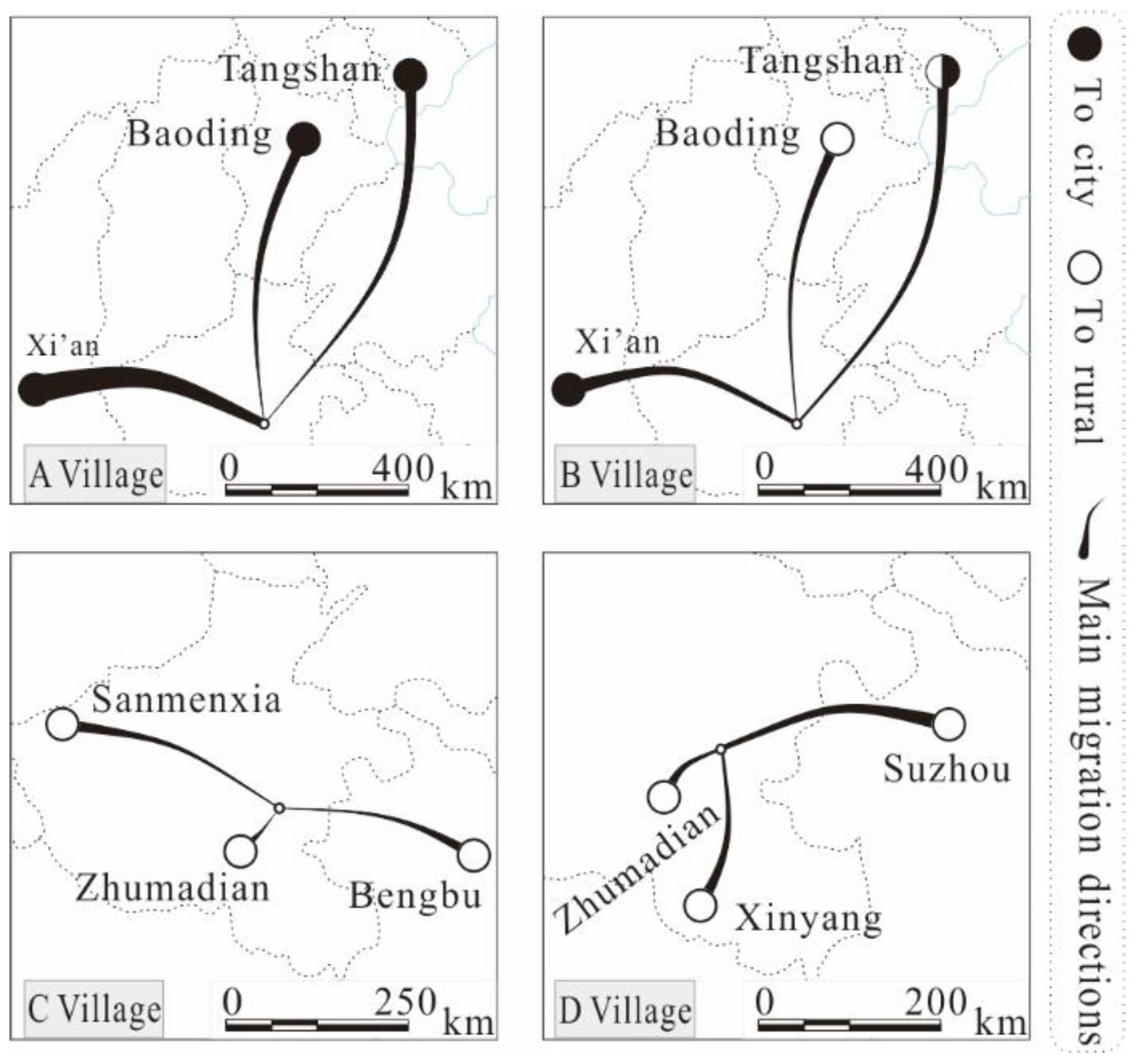

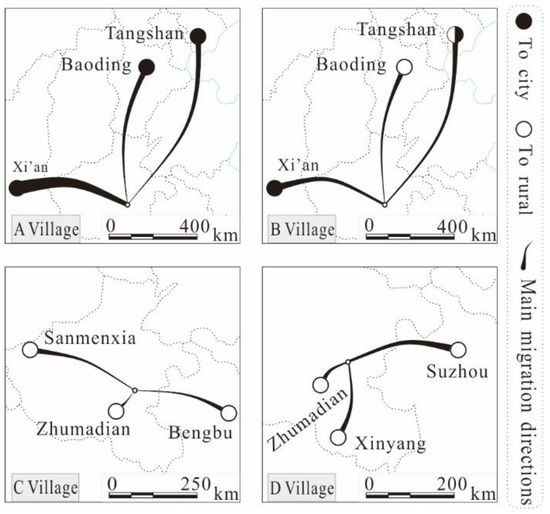

3.2.1. Chain Migration: Neighboring Outflow Places, Similar Inflow Places

Relying on relationship networks, chain actors always select the same or close destinations. When farmers migrate to the cities or other areas to engage in selling fried dough sticks, they often obtained information or various forms of support from their acquaintances who have migrated. We conducted kernel density estimation on the migration destination (Figure 4). In Village A, from 1990 to 2000, farmers of making fried dough sticks in Village A mainly migrated to Zhengzhou within a medium and short distance from their village. More long-distance migration gradually occurred after 2000, such as Xi’an. As time went on, the diversity of migration destination decreased, and showed a concentrated and stable trend. After 2010, farmers in respect to making fried dough sticks in Village A concentratedly selected Xi’an as the migrate destination.

Figure 4.

Changes of inflow places in Village A.

In addition, we compared the migration destination of the farmers of selling fried dough sticks from different villages. We identified migration destination of farmers from Village A, Village B, Village C and Village D (Figure 5). The farmers in Village A mainly flowed into Xi’an, Tangshan and Baoding, farmers in Village B also flowed into Xi’an, Tangshan and Baoding. However, farmers in Village C mainly flowed into Sanmenxia, Zhumadian and Bengbu, and farmers in Village D mainly flowed into Suzhou, Zhumadian and Xinyang with short distance. It was found farmers who sold fried dough sticks from Village A and Village B selected the close migration destination. The similarity of the migration space depended on the closeness of acquaintances-based relationships. In Dengcheng Town, Village B was adjacent to Village A, farmers obtained information from acquaintances depending on the geographical proximity of relationship networks.

Figure 5.

The main inflow places in each village.

3.2.2. Earthbound Farmers: Mobility and Flexibility

The size of per capita cultivated land in Dengcheng Town decreased from the southwest to the northeast at the village scale. In Village A and Village B, per capita cultivated land was small, amounting to 0.044 ha and 0.041 ha, respectively. Most farmers in Village A and Village B chose to sell fried dough sticks in cities with long distance (Table 1). With the support of social relationship networks, increasing more farmers who sell fried dough sticks gradually flowed into cities all year round, and even settled in the cities. It showed that 72.8% of the farmers who sell fried dough sticks settled in the cities in Village A. In Village B, 29.4% of the farmers who sell fried dough sticks settled in the cities. Farmers who sell fried dough sticks with smaller-scale cultivated land moved to cities with greater urgency.

Table 1.

The locations of the villages and the differences in mobility modes.

On the contrary, the farmers in Village C and Village D had more per capita cultivated land, amounting to 0.071 ha and 0.088 ha, respectively. Most farmers in Village C and Village D chose to manage their fried dough sticks businesses in the countryside with short distance, as it was convenient for them to return home to carry out agricultural work. Even after they started their fried dough sticks businesses, they still “left the land but not the countryside”. The proportion of farmers in Villages C and D who sold fried dough sticks in the countryside all the time was as high as 89.5%. They flowed into the places when busy farming season and return hometown during the slack farming season of inflow places, such that the flow mode was comparable to that of migratory birds. A farmer from Village C remarked, “My husband and I are just like making a living wandering from place to place. We have spent all our time in the countryside and have never been to the city. We only spent one year or two years selling fried dough sticks in the same place. Because we always sell in the same village, people seem to be tired of it. So, we need to carry out our businesses in another place”.

In village A, the age at which people start to learn the skills of making fried dough sticks, was the earliest. The proportion of vendors who started to learn how to make fried dough sticks before the age of 18 was the highest in Village A, reaching 56.5%. The proportion observed in Village B, Village C and Village D was 41.9%, 33.3% and 23.1%, respectively, which showed a gradual decrease. The proportion of vendors in Village A, Village B, Village C and Village D who started to learn how to make fried dough sticks after the age of 25 was 23.9%, 25.8%, 36% and 61.5%, respectively, which showed a gradual increase. In other words, larger size of per capita cultivated land was associated with learning fried dough sticks skills at a later age.

3.2.3. Contented Farmers: Complementarity and Continuity

Since ancient times, Chinese farmers have been nostalgic about their hometown, and they relied on the land as a primary source of income. In terms of farmers’ lifestyles, choice was limited by the amount of cultivated land that they hold. They naturally prioritized an earthbound lifestyle. Farmers with larger amounts of cultivated land were unwilling to entirely give up the income from cultivated land. So, they were more likely to flow into countryside, which was flexible and mobile in selling fried dough sticks. It was convenient for them to return home to carry out agricultural work. However, farmers with smaller amounts of cultivated land suffered from higher levels of stress, and they were more motivated to break away entirely from the constraints associated with their land.

Selling fried dough sticks in the countryside, can be regarded as a continuation of the traditional part-time livelihood model. Many farmers who sell fried dough sticks have flowed to specialized agricultural areas. Dangshan County located in Suzhou City, was rich in pears, peaches and other fruits. In July, it was time to harvest fruits. During this time, local farmers were busy with agricultural work and had no time to prepare meals. Fried dough sticks became a staple food for breakfast and dinner. It happened to be the slack farming season in the hometown of farmers who sell fried dough sticks in July. Therefore, they were attracted to Dangshan. They usually set up stalls at different road intersections in the morning and evening. However, the market was limited for them in the countryside. When the competition became fiercer among them, they became vulnerable to forces of the market. In professional agricultural villages, local farmers had also begun to pay attention to learning skills by means of training or learning from acquaintances during recent years. Many breakfast or fried dough sticks stalls have sprung up, which resulted in poorer businesses prospects for vendors from other places.

Low profitability was the main reason for farmers who selling fried dough sticks in the countryside to change the location. Therefore, under changes in external market conditions, the proportion of rural vendors who chose to settle down was low, which was 25% and 16.7% in Villages C and D, respectively (Table 1). It was indicated that this livelihood strategy was fragile and unsustainable.

4. Discussion

Relationship network formed by embedding farmers’ behaviors in the spatial situation [42]. From a spatial perspective, the establishment and maintenance of relationship network in an acquaintance-based society largely depends on small-scale interpersonal interactions, which are constrained by the location and connection of actors [43]. Therefore, as a socio-economic actor, the individual’s relationship networks are shaped by spatial situation, which is characterized by location, connectivity and context. In this sense, socio-economic phenomena are no longer the inherent attributes of the actors, but the expression and product of their relationships in spatial situation. Based on farmers’ location, this paper described the process of skill learning and chain migration within the context of a reliance on relationships. It corresponds to Fei Xiaotong’s views of the study of social relationships. He believed that the location of residences was an important way of understanding the connectivity of social relations [17].

It is helpful to understand the occurrence, dissemination and constraints of the relationship network behind socio-economic behaviors [44]. On the one hand, opportunities for interpersonal communication benefit from the proximity of spatial locations. For example, the phenomenon of skill diffusion and chain migration was affected by spatial proximity in rural acquaintance-based society. On the other hand, changes in the individual’s livelihoods are related to the relative conditions determined by spatial context. For instance, the size of cultivated land affected the choices available to farmers in respect to their livelihoods. In addition, the difference between rural and urban market conditions affects the stability. Therefore, putting individual behavior in spatial situation allows for a deep exploration of the social spatial embeddedness of economic activities.

The livelihood strategies and regional culture over the long-term shaped by spatial situations. Therefore, researchers should focus on examining regional differences and the constraints that are attached to daily activities. For example, the social relationships of villages in the Yellow River Basin show aggregation and collectivity. This is significantly different from the dispersion and individuality of villages in the Yangtze River Basin [45]. It is helpful to gain a better understanding of regional culture and livelihoods change. With increasing mobility, more and more farmers have begun to take up part-time non-agricultural employment as a major livelihood. This lifestyle chosen by contemporary Chinese farmers actual continues, the earthbound cultural way of life. As some scholars have realized, China’s new urbanization mode urgently needs a flexible model, which should focus on reliable, low-cost and sustainable forms of livelihood, particularly in terms of part-time employment [46]. Although part-time businesses are more flexible, they become unstable with market changes. Therefore, the development of rural industry forms should more fully consider the spatiotemporal complementarity of the industry, so as to create a more sustainable livelihood.

China’s rural community is made up of people who are familiar with each other. Rural households’ socio-economic behaviors are not only the result of individual decision-making, but also conform to group decision-making [47,48]. They often obtain information or various forms of support from their acquaintances [49]. This paper has confirmed that farmers mainly considered the channels of neighborhood in their relationship networks. In practice, we should actively shape the scope of the social space when examining neighborhood identity, as this can help villagers to quickly seize opportunities by relationships and dynamize their collective action. At the same time, we should pay attention to providing farmers, and those with weak relationships, with necessary training and assistance.

In this paper, we focused on the relationships among actors in terms of skill learning and the migration of farmers. However, we have not described the location of the floating farmers in new places and relationship proximity among them. Future research on relationship networks are encouraged to explore more diverse relationships and proximities among actors and examine regional differences and the constraints that are attached to daily activities.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we focused on two types of spatial situations: individual resident situation and group migration situation. We used data in the specialized village of fried dough sticks and paid attention to the proximity of residences and the geographical context of migration, as to understand the occurrence and change process of chain migration. This is crucial to gaining a deeper understanding of the relationship networks that comprise a rural Chinese acquaintance-based society. The main conclusions are as follows. (1) Geographical closeness played an important role on the skill learning of farmers. In Village A and Village C, 73.9% and 52% of the farmers, respectively, learned the skill from their own villagers, whereas 12.9% and 7.7% of the farmers in Village B and Village D, respectively, learned this skill from their own villagers. It promoted that the number of farmers with making fried dough sticks and years of farmers engaging in fried dough sticks business in Village A and Village C were higher than that in Village B and Village D. (2) The establishment of master-prentice relationship networks was related to the spatial proximity of farmers’ dwellings. The space of skill learning was highly consistent with the spatial distribution of the master-prentice relationships. Master-prentice relationship networks were mainly concentrated in the third and fourth villagers’ group. In addition, skill learning in respect to making fried dough sticks mainly occurred in the third and fourth villages’ group. (3) The closer the spatial distance of farmers, the closer the migration destination they choose. For example, Village B was adjacent to Village A in Dengcheng Town. In addition, farmers who sold fried dough sticks from Village A and Village B selected the close migration destination. In terms of spatial constraints, farmers in Village A and Village B had less per capita cultivated land, and they tended to migrate to the cities with long distance. Farmers in Village C and Village D had more per capita cultivated land, and they were more likely to migrate to rural areas with short distance, as it was convenient for them to return home to carry out agricultural work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.H. and X.L.; methodology, X.H. and R.Z.; software, R.Z.; validation, X.L., X.H., R.Z. and Y.S.; formal analysis, X.H.; investigation, Q.W.; resources, X.H. and Q.W.; data curation, Y.S.; writing—original draft preparation, X.H., R.Z., Y.S. and Q.W.; writing—review and editing, X.H.; visualization, Y.S. and Q.W.; supervision, X.L.; project administration, X.H. and X.L.; funding acquisition, X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 41971223. Key Research Institute of Yellow River Civilization and Sustainable Development and Collaborative Innovation Center on Yellow River Civilization of Henan University, grant number 2020M18.

Acknowledgments

We deeply appreciate Wenxian Jiao at Henan University and Ning Niu at Henan University of Economics and Law for valuable writing advice for this paper. We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for giving the insightful suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Granovetter, M. Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. Am. J. Sociol. 1985, 91, 481–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, M. Embeddedness, the new food economy and defensive localism. J. Rural Stud. 2003, 19, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, M.; Knickel, K.; Díaz-Puente, J.; Afonso, A. The role of social capital in agricultural and rural development: Lessons learnt from case studies in seven countries. Sociol. Rural. 2019, 59, 66–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Santos, J.; Roldan, L.; Loo, M. Clarifying relationships between networking, absorptive capacity and financial performance among South Brazilian farmers. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 84, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, Y.; Asafu-Adjaye, J.; Kassie, M.; Mallawaarachchi, T. Do neighbours matter in technology adoption? The case of conservation tillage in northwest Ethiopia. Afr. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2016, 11, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamiit, R.; Gray, S.; Yanagida, J. Characterizing farm-level social relations’ influence on sustainable food production. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 86, 566–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepic, M.; Trienekens, J.; Hoste, R.; Omta, S. The influence of networking and absorptive capacity on the innovativeness of farmers in the Dutch pork sector. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2012, 15, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara-Rojas, R.; Bravo-Ureta BDíaz, J. Adoption of water conservation practices: A socioeconomic analysis of small-scale farmers in Central Chile. Agric. Syst. 2012, 110, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y.; Yang, Y. The sociology of guanxi as the subject discourse of China. J. Humanit. 2019, 9, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, H.; Kim, S. The relationship between networking behaviors and the Big Five personality dimensions. Career Dev. Int. 2012, 17, 43–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. The transformation of rural China and the formation of post-vernacular characteristics. J. Humanit. 2010, 5, 161–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, K.; Vella, F. Immigrant networks and their implications for occupational choice and wages. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2013, 95, 1249–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ciupijus, Z.; Forde, C.; Mackenzie, R. Micro-and meso-regulatory spaces of labour mobility power: The role of ethnic and kinship networks in shaping work related-movements of post-2004 Central Eastern European migrants to the United Kingdom. Popul. Space Place 2020, 26, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L. The tendency of fellow townsmen being in the same trade: A tradition in the Southeast Asian Chinese Communities. Open Times 2014, 1, 210–223. Available online: http://www.opentimes.cn/html/Journal/20665.html (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Liu, Q. Study on the effect of social network on homeplace-based settlement of rural-urban migrant population. Econ. Sci. 2020, 2, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Social network analysis of rural population migration during 1978–2016: Evidence from A Village of a population net-outflow province, middle area of China. Issues Agric. Econ. 2018, 3, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X. Earthbound China, Fertility System, Rural Reconstruction; The Commercial Press: Beijing, China, 2007; pp. 27–220. [Google Scholar]

- Abizaid, C.; Coomes, O.; Takasaki, Y.; Mora, J. Rural social networks along Amazonian Rivers: Seeds, labor and soccer among communities on the Napo River, Peru. Geogr. Rev. 2018, 108, 92–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luo, J.; Sun, Y. Phenomena of capable persons in the Functioning of self organizations. Soc. Sci. China 2013, 10, 86–101. Available online: https://www.sklib.cn/c/2014-03-03/607872.shtml (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Qiao, J.; Yang, J. Recent progress in the specialized village study of China. Hum. Geogr. 2013, 28, 76–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Li, C.; Zhou, D.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J. Peasant households’ land use decision-making analysis using social network analysis: A case of Tantou Village, China. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 80, 452–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glückler, J. Economic geography and the evolution of networks. J. Econ. Geogr. 2007, 7, 619–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qian, Q.; Chen, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, J.; Chen, C. Development characteristics and formation mechanism of taobao town: Taking Xintang Town in Guangzhou as an example. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2017, 37, 1040–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Qiu, D.; Shen, Y.; Guo, H. Study on the formation of taobao village: Taking Dongfeng Village and Junpu Village as examples. Econ. Geogr. 2015, 35, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xie, L. The aggregation and entrepreneurship of the business-driven immigrants: Taking the chaozhou-shantou businessmen in Guangzhou wholesale &retail market for example. J. Guangxi Univ. Natl. 2010, 32, 78–83. Available online: https://navi.cnki.net/knavi/journals/GXZS/detail (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Wu, Z. “Social Economy” or “Low—End Nationalization”? J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 2020, 20, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X. Spatial turn in social theories. Chin. J. Sociol. 2006, 2, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Su, Y.; Liu, J. A methodological discussion of spatialized social network: A case study on social and geographical network of the Shenzhen media industry. Hum. Geogr. 2013, 28, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelmann, H.; Quiñones-Ruiz, X.; Penker, M. Analytic framework to determine proximity in relationship coffee models. Sociol. Rural. 2020, 60, 458–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borgatti, S.; Mehra, A.; Brass, D.; Labiance, G. Network analysis in the social sciences. Science 2009, 323, 892–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caplow, T.; Forman, R. Neighborhood interaction in a homogeneous community. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1950, 15, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Payne, D. Characteristics of Chinese rural networks: Evidence from villages in Central China. Chin. J. Sociol. 2017, 3, 74–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellman, B. Are personal communities local? A dumptarian consideration. Soc. Netw. 1996, 18, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. New Approaches to Economic Geography: A Chinese Perspective; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2016; pp. 151–485. [Google Scholar]

- McKitterick, L.; Quinn, B.; McAdam, R.; Dunn, A. Innovation networks and the institutional actor-producer relationship in rural areas: The context of artisan food production. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 48, 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcpherson, M.; Smith-Lovin, L.; Cook, J.M. Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2001, 27, 415–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Z.; Liu, Y. Beyond spatial segregation: Neo-migrants and their social networks in Chinese cities. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2011, 66, 785–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodchild, M.; Janelle, D. Toward critical spatial thinking in the social sciences and humanities. GeoJournal 2010, 75, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schramski, S.; Huang, Z. Spatial social network analysis of resource access in rural south Africa. Prof. Geogr. 2016, 68, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Su, H. A review of social atlas research. Prog. Geogr. 2015, 34, 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, N.; Li, X.; Li, L. Exploring the spatio-temporal dynamics of development of specialized agricultural villages in the underdeveloped region of China. Land 2021, 10, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Hesterly, W.; Borgatti, S. A general theory of network governance: Exchange conditions and social mechanisms. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1997, 22, 911–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Glückler, J.; Panitz, R. Unleashing the potential of relational research: A meta-analysis of network studies in human geography. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2021, 45, 1531–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Hu, Y.; Li, G. Economic sociology and behavioral geography: The affinity and the complementarity. Sociol. Rev. China 2018, 6, 3–12. Available online: http://src.ruc.edu.cn/CN/Y2018/V6/I5/3 (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Xu, Y. “Separation” and “Combination”: Classification of rural regional villages from the perspective of qualitative research. Shandong Soc. Sci. 2016, 7, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z. Flexible urbanization: A hypothesis based on pluriactivity and mobility of rural employment. City Plan. Rev. 2016, 40, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y. Favour and power in the acquaintance society: Interpreting a conflict in White Deer Plain. Int. J. Law Soc. 2021, 4, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, J. Energy utilization of pig breeding waste at the acquaintance society and atomized society in rural areas: Game analysis, simulation analysis and reality testing. J. Nat. Resour. 2020, 35, 2484–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Li, X.; Qiao, J. The relationship between households’ behavior and the formation of specialized village: A case study of plywood processing of Shilaoba Specialized Village, Zhecheng County in Henan Province, China. Sci. Geogr. Sin. 2014, 34, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).