The Culture-Centered Development Potential of Communities in Făgăraș Land (Romania)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

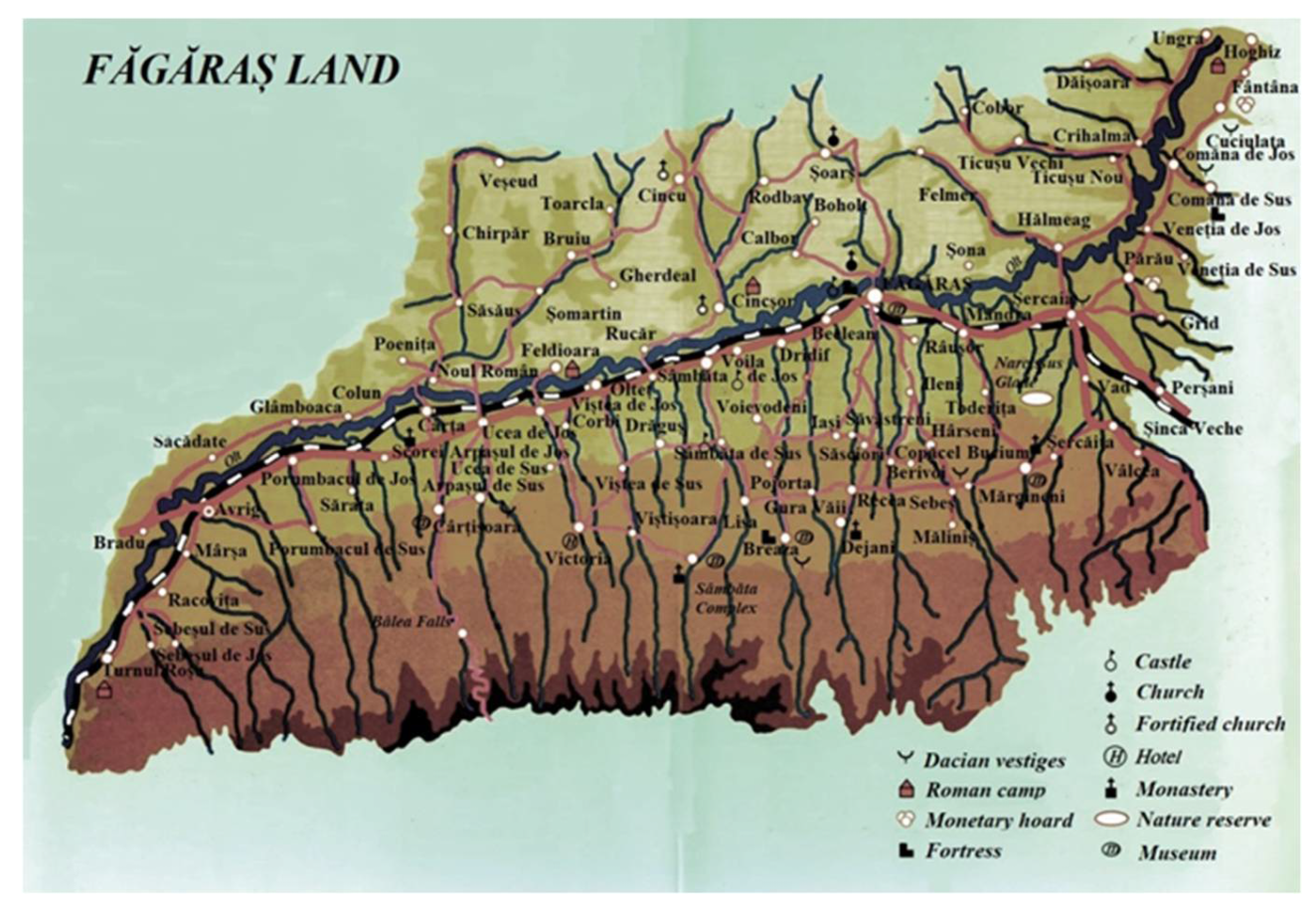

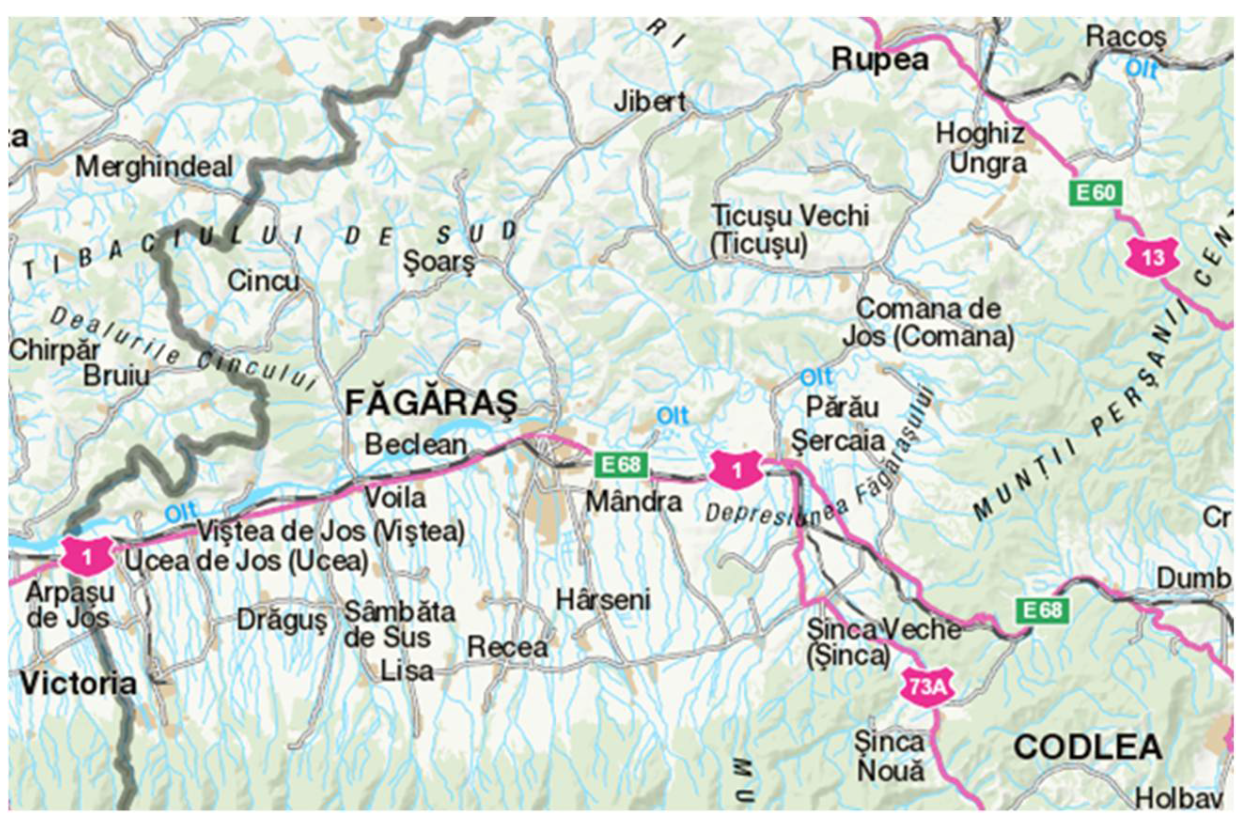

2.1. Făgăraș Land, Geographical and Historical Background

The Compossessorates, Local Commons of Făgăraș Land

2.2. Methodological Approach

3. Results

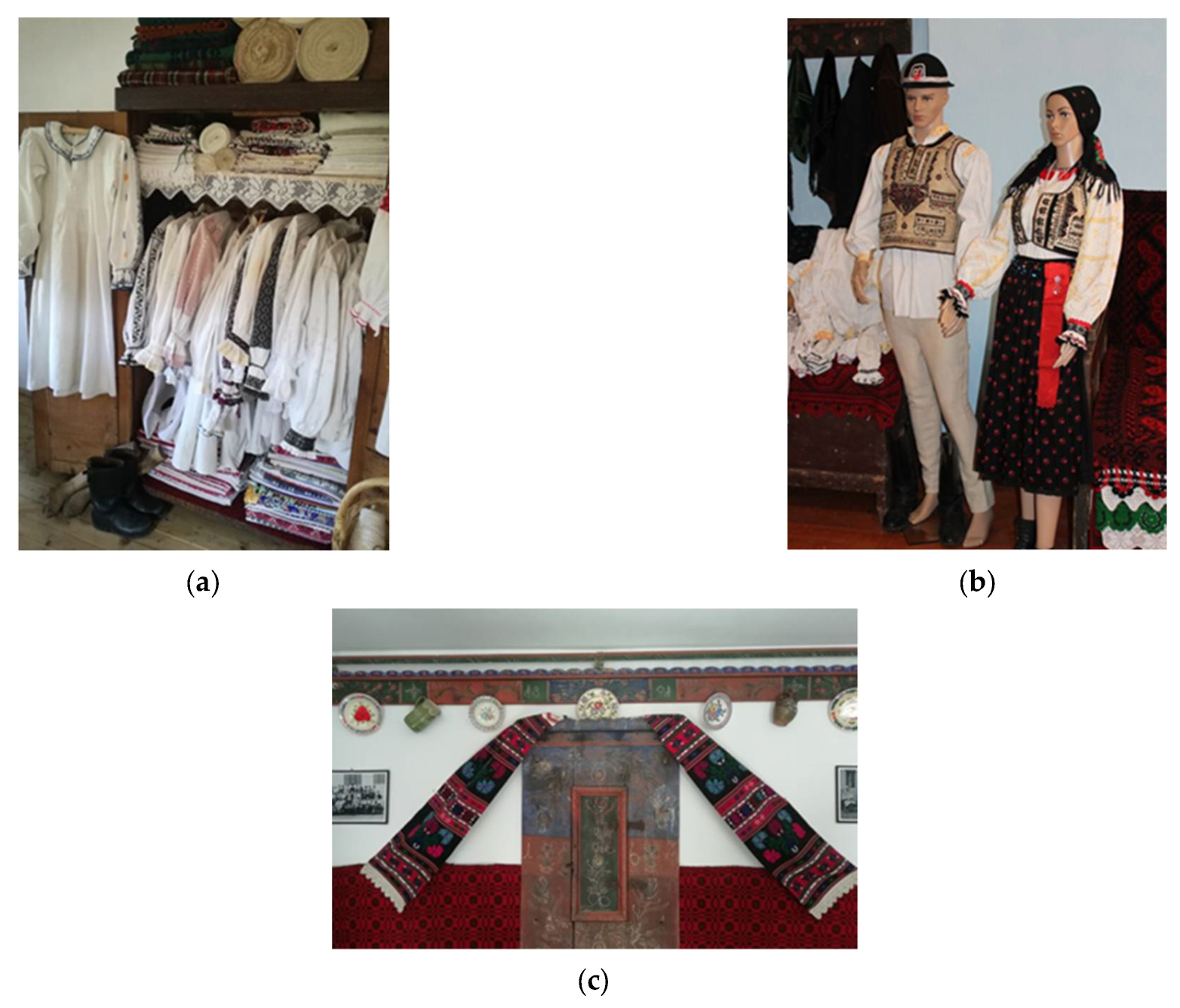

3.1. Resources of Făgăraș Land as a Multidimensional Associative Cultural Landscape

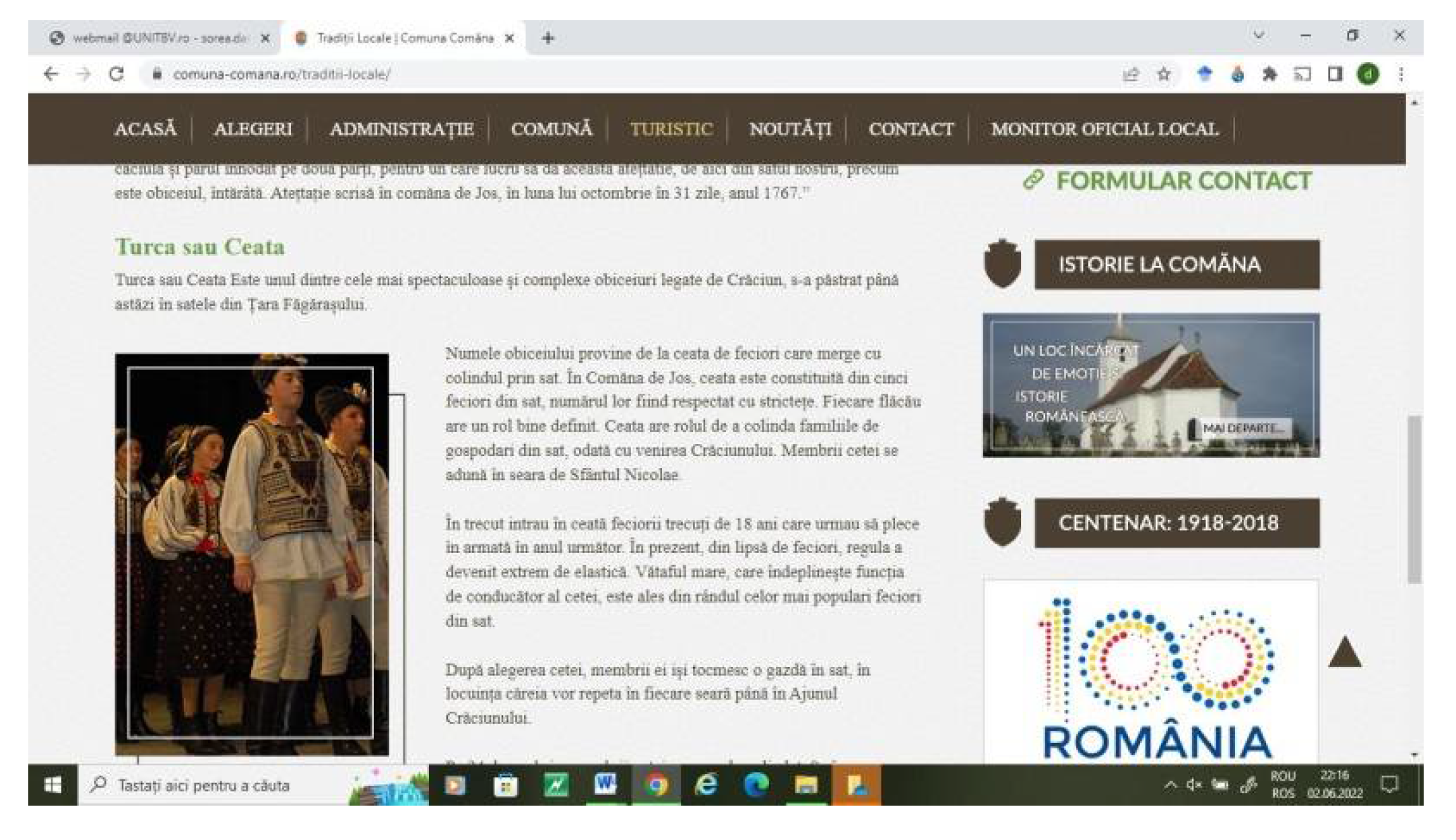

3.1.1. Groups of Carolling Lads and Foster Christmas Relatives in Făgăraș Land

3.1.2. Sour Soups of Făgăraș Land as a Gastronomic Brand

3.1.3. Unitary Character of ICH Resources in Făgăraș Land

3.1.4. Some Community Initiatives to Capitalize on ICH Resources

3.1.5. The Fortresses of Făgăraș Land as Cultural Tourism Objectives

3.1.6. Anti-Communist Resistance in Făgăraș Land as a Challenge for Cultural Tourism

3.1.7. Orthodox Monasteries of Făgăraș Land

3.1.8. Făgăraș Land, a Potențial Cultural Landscape

3.1.9. Some Dimensions of the Tourist Potential of the Natural Landscape in Făgăraș Land

3.2. Approaching ICH Resources in Town Halls of Făgăraș Land

3.2.1. Online Promotion of ICH Resources on the Town Hall Websites

3.2.2. Types of Local Narratives about the ICH Resources

- (a)

- Glocal vision—the commune as a global network node (the leaders knew the lines of international policies, trying to apply them at the local level: emphasis on understanding the mechanisms of sustainable development, obvious extra-local openings, availability for association and inter-community cooperation, promotion of local identity and resources);

- (b)

- Dynamic local vision—the commune as a stage (the leaders felt that the unique, specific local identity was worth communicating to visitors: emphasis on promoting identity and resources abroad);

- (c)

- Static local vision—the commune as a protected area (leaders believed that the unique, specific local identity must be protected: emphasis on strict preservation of tradition, with no interest in promoting it outside the community).

3.3. Suggestions of Efficient Capitalization on the Cultural Potential for the Sustainable Development of Făgăraș Land

3.3.1. Unitary Approach to Resources of Făgăraș Land

3.3.2. Integrated Approach to Resources of Făgăraș Land

3.3.3. Consolidation of Local Cultural Identity

3.3.4. A Challenge for Local Entrepreneurs

3.3.5. Support from the Compossessorates in Făgăraș Land

3.3.6. Better Management of Local Cultural Potential at the Level of Town Halls

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Research Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sauer, C.O. The Morphology of Landscape; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1925. [Google Scholar]

- Hartshorne, R. The nature of geography: A critical survey of current thought in the light of the past. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 1939, 29, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antrop, M. Antrop, M. A brief history of landscape research. In The Routledge Companion to Landscape Studies; Howard, P., Thompson, I., Waterton, E., Atha, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 12–23. [Google Scholar]

- Rowntree, L.B. The cultural landscape concept in American human geography. In Concepts in Human Geography; Earle, C., Mathewson, K., Kenzer, M.S., Eds.; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 1996; p. 127. [Google Scholar]

- Meining, D.W. The Beholding Eye ten versions of the same scene. In The Interpretation of Ordinary, Landscapes; Meining, D.W., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1979; pp. 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, P. Perceptual lenses. In The Routledge Companion to Landscape Studies; Howard, P., Thompson, I., Waterton, E., Atha, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 43–53. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. 1996, Report of the Expert Meeting on European Landscapes of Outstanding Universal Value, World Heritage Committee, Vienna, 24–29 June 1996. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/europe7.htm (accessed on 19 May 2022).

- Oliveira, M.D.; Ribeiro, J.T. Landscape (European Landscape Convention) vs. Cultural Landscape (UNESCO): Towards territorial development based on heritage values. In Heritage 2012; Amoeda, R., Lira, S., Pinheiro, C., Eds.; Greenlines Institute for Sustainable Development: Porto, Portugal, 2012; pp. 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO World Heritage Convention. 23rd Session of the General Assembly of States Parties. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/sessions/23GA (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Council of Europe. Council of Europe Landscape Convention. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/landscape (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Brown, J.; Mitchell, N.; Beresford, M. (Eds.) The Protected Landscape Approach Linking Nature, Culture and Community; IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas: Cambridge, UK. Available online: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2005-006.pdf (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Plieninger, T.; van der Horst, D.; Schleyer, C.; Bieling, C. Sustaining ecosystem services in cultural landscapes. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirvani Dastgerdi, A.; Sargolini, M.; Broussard Allred, S.; Chatrchyan, A.; De Luca, G. Climate Change and Sustaining Heritage Resources: A Framework for Boosting Cultural and Natural Heritage Conservation in Central Italy. Climate 2020, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keles, E.; Atik, D.; Bayrak, G. Visual Landscape Quality Assesment in Historical Cultural Landscape Areas. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 7, 287–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jelen, J.; Stantruckova, M.; Komarek, M. Typology of historical cultural landscapes based on their cultural elements. Geografie 2021, 126, 243–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strantuckova, M.; Weber, M. Identification of Values of the Designed Landscapes: Two Case Studies from the Czech Republic. In Biocultural Diversity in Europe. Environmental History; Agnoletti, M., Emanueli, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 487–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Guidelines on the Inscription of Specific Types of Properties on the World Heritage List. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/archive/opguide08-en.pdf#annex3 (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- The Cultural Landscape Foundation. About Cultural Landscapes. Available online: https://www.tclf.org/places/about-cultural-landscapes (accessed on 3 March 2022).

- Rossler, M. World heritage and cultural landscapes: A UNESCO flagship programme 1992–2006. Landsc. Res. 2006, 31, 333–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirisrisak, T.; Akagawa, N. Cultural landscape in the world heritage list: Understanding on the gap and categorisation. City Time 2007, 2, 11–20. [Google Scholar]

- Flint, R.F. Practice of Sustainable Community Development. A Participatory Framework for Change; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO: Culture for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/themes/culture-sustainable-development (accessed on 22 April 2019).

- Al-Ansi, A.; Lee, J.-S.; King, B.; Han, H. Stolen history: Community concern towards looting of cultural heritage and its tourism implications. Tour. Manag. 2021, 87, 104349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, T.; Han, H. Community-based tourism (TourDure) experience program: A theoretical approach. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 956–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, H.; Han, H. Tourist experience quality and loyalty to an island destination: The moderating impact of destination image. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva-Álvaro, J.-J.; Mondéjar-Jiménez, J.; Sáez-Martínez, F.-J. Rural Tourism: Development, Management and Sustainability in Rural Establishments. Sustainability 2017, 9, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aquino, R.S.; Lück, M.; Schänzel, H.A. A conceptual framework of tourism social entrepreneurship for sustainable community development. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 37, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, G.; Citro, E.; Salvia, R. Economic and Social Sustainable Synergies to Promote Innovations in Rural Tourism and Local Development. Sustainability 2016, 8, 668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dujmović, M. Komercijalizacija kulturne baštine u turizmu. Soc. Ekol. 2019, 28, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cocola-Gant, A.; Hof, A.; Smigiel, C.; Yrigoy, I. Short-term rentals as a new urban frontier—Evidence from European cities. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2021, 53, 1601–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalina, P.D.; Dupre, K.; Wang, Y. Rural tourism: A systematic literature review on definitions and challenges. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 134–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, L.; Du Preez, E.A.; Fairer-Wessels, F. To wish upon a star: Exploring Astro Tourism as vehicle for sustainable rural development. Dev. S. Afr. 2020, 37, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sert, A.N. Niche Marketing and Tourism. J. Bus. Manag. Econ. Res. 2017, 1, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsani, N.T.; Shafiei, Z.; Saffari, B. Tourism Strategies for Rural Economic Prosperity (Case Study: Iran). Curr. Politics Econ. Middle East 2017, 8, 111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson, P.; Quarter, J. A Theoretical Framework for Community-Based Development. Econ. Ind. Democr. 1995, 16, 525–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, R.C.; Hashim, N.A.A.N.; Awang, Z. Tourism Development in Rural Areas: Potentials of Appreciative Inquiry Approach. J. Tour. Hosp. Culin. Arts 2018, 10, 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Ohe, Y. Community-Ased Rural Tourism and Entrepreneurship. A Microeconomic Approach; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mannon, S.E.; Glass-Coffin, B. Will the Real Rural Community Please Stand Up? Staging Rural Community-Based Tourism in Costa Rica. J. Rural. Community Dev. 2019, 14, 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Newsome, D.; Moore, S.A.; Dowling, R.K. Natural Area Tourism: Ecology, Impacts and Management; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lotter, M.; Geldenhuys, S.; Potgieter, M. A conceptual framework for segmenting niche tourism markets. In Proceedings of the 6th International Adventure Conference (IAC), Segovia, Spain, 30 January–2 February 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, G. Cultural tourism: A review of recent research and trends. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2018, 36, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, S.; Hall, C.; Fagnoni, E. Managing world heritage site stakeholders: A grounded theory paradigm model approach. J. Herit. Tour. 2019, 14, 308–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, M.; Seyfi, S.; Hall, C.; Hatamifar, P. Understanding memorable tourism experiences and behavioural intentions of heritage tourists. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 21, 100621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmelash, A.G.; Kumar, S. The structural relationship between tourist satisfaction and sustainable heritage tourism development in Tigrai, Ethiopia. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yi, X.; Fu, X.; Yu, L.; Jiang, L. Authenticity and loyalty at heritage sites: The moderation effect of postmodern authenticity. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnaiz-Schmitz, C.; Dantos, L.; Herrero-Jáuregui, C.; Rodríguez, P.D.; Pineda, F.D.; Schmitz, M.F. Rural Tourism: Crossroads between nature, socio-ecological decoupling and urban sprawl. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2018, 227, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dai, T.; Zheng, X.; Yan, J. Contradictory or aligned? The nexus between authenticity in heritage conservation and heritage tourism, and its impact on satisfaction. Habitat Int. 2021, 107, 102307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dans, E.P.; González, P.A. Sustainable tourism and social value at World Heritage Sites: Towards a conservation plan for Altamira, Spain. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 74, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyser, H. Tourism Development; Oxford University Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, H.E.; Henriques, F.M.A. The impact of tourism on the conservation and IAQ of cultural heritage: The case of the Monastery of Jerónimos (Portugal). Build. Environ. 2021, 190, 107536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, I.-A. Transilvania în secolul al XIV-lea şi prima jumătate a secolului al XV-lea (cca 1300–1456). In Istoria Transilvaniei (Până la 1541); Pop, I.-A., Nägler, T., Eds.; CST Institutul Cultural Român: Cluj Napoca, Romania, 2003; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Andreescu, Ș. Vlad Țepeș Dracula. Între Legendă și Adevăr Istoric; Univers Enciclopedic: București, Romania, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Băjenaru, C. Ţara Făgăraşului în Timpul Stăpânirii Austriece (1691–1867); ALTIP: Alba Iulia, Romania, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Opincaru, I.-S. Mountain commons and the social economy in Romania. In Proceedings of the Practicing the Commons: Self-Governance, Cooperation and Institutional Change Conference, Utrecht, The Netherland, 10–14 July 2017; Available online: http://dlc.dlib.indiana.edu/dlc/bitstream/handle/10535/10376/12B_Opincaru.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- Vasile, M. Forest and Pasture Commons in Romania. Territories of Life, Potential ICCAs: Country Report. 2019. Available online: https://www.iccaconsortium.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/CommonsRomaniaPotentialICCAS2019.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- Petrescu, C.; Stănilă, G. Ancheta sociologică asupra asociaţiilor agricole şi obştilor/composesoratelor. In Organizaţiile Colective ale Proprietarilor de Terenuri Agricole și Forestiere; Petrescu, C., Ed.; Polirom: Iași, Romania, 2013; pp. 129–141. [Google Scholar]

- Vasile, M.; Măntescu, L. Property reforms in rural Romania and community-based forests. Sociol. Româneascã 2009, VII, 95–113. [Google Scholar]

- Opincaru, I.-S. Elements of the institutionalization process of the forest and pasture commons in Romania as particular forms of social economy. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2021, 92, 101–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vameșu, A.; Barna, C.; Opincaru, I. From public ownership back to commons. Lessons learnt from the Romanian experience in the forest sector. In Providing Public Goods and Commons. Towards Coproduction and New Forms of Governance for a Revival of Public Action; Bance, P., Zaïd-Chertouk, M.A., Álvarez, J.F., Barna, C., Bauby, P., Moreira, M.B., Boual, J.-C., Combes-Joret, M., Glemain, P., Gordo, M., et al., Eds.; CIRIEC Studies Series; Université de Liège: Liège, Belgium, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- Romanian Mountain Commons Project. Available online: https://romaniacommons.wixsite.com/project (accessed on 18 May 2020).

- Chiburțe, L. Teoria accesului la resursele naturale și practicile sociale de exploatare a pădurilor. Sociol. Românească 2008, 6, 116–126. [Google Scholar]

- Vasile, M. Formalizing commons, registering rights: The making of the forest and pasture commons in the Romanian Carpathians from the 19th century to post-socialism. Int. J. Commons 2018, 12, 170–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouriaud, L. Proprietatea si dreptul de proprietate asupra padurilor intre reconstituire si re-compunere. An. Univ. Ștefan Cel Mare Suceava-Secțiunea Silvic. 2008, 10, 5–20. [Google Scholar]

- Cotoi, C.; Mateescu, O. Economie Socială, Bunuri ăi Proprietăți Comune în România; Polirom: Iasi, Romania, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Verdery, K. Property and Power in Transylvania’s decollectivisation. In Renewing the Anthropological Tradition; Hann, C.M., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998; pp. 160–181. [Google Scholar]

- Verdery, K. The Vanishing Hectare: Property and Value in Postsocialist Transylvania; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Duxbury, N.; Garrett-Petts, W.F.; MacLennan, D. Introduction to an Emerging Field of Practice. In Cultural Mapping as Cultural Inquiry; Duxbury, N., Garrett-Petts, W.F., MacLennan, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Balfour, B.; Fortunato, M.W.P.; Alter, T.R. The creative fire: An interactional framework for rural arts-based development. J. Rural. Stud. 2018, 63, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Basic Texts of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Tourism Organization. Tourism and Intangible Cultural Heritage; UNWTO: Madrid, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- CarPaTO—Cartografierea Patrimoniului Cultural Imaterial în Țara Făgărașului. Raport de Cercetare in Extenso. Available online: https://www.unitbv.ro/documente/cercetare/rezultatele-cercetarii/rapoarte/2_Raport_Cartografierea_patrimoniului_cultural_2019.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Brancati, D. Social Scientific Research; Sage: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Moezzi, M.; Janda, K.B.; Rotmann, S. Using stories, narratives, and storytelling in energy and climate change. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 31, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, N.F.; Cohen, S.A.; Scarles, C. The power of social media storytelling in destination branding. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 8, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Csesznek, C. Storytelling—O abordare sociologică. In Storytelling între Drum și Destinație; Csesznek, C., Coman, C., Eds.; C.H.Beck: Bucharest, Romania, 2020; pp. 9–46. [Google Scholar]

- Cersosimo, G. Digital Storytelling; SAGE: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Guimarães Pereira, A.; Funtowicz, S. VISIONS for Venice in 2050. Aleph, story telling and unsolved paradoxes. Futures 2013, 47, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro-Naval, V.; Serra, P. How Do Destinations Frame Cultural Heritage? Content Analysis of Portugal’s Municipal Websites. Sustainability 2019, 11, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sorea, D.; Csesznek, C. The Groups of Caroling Lads from Făgăras, Land (Romania) as Niche Tourism Resource. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolborici, A.M.; Lupu, M.I.; Sorea, D.; Atudorei, I.A. Gastronomic Heritage of Făgăraș Land: A Worthwhile Sustainable Resource. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorea, D.; Băjenaru, E. Couple villages from the Făgăraș Land, with their history and ethnographic peculiarities. Int. Conf. Knowl. -Based Organ. 2019, XXV, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De 300 de ani avem cete în Ţara Făgăraşului De 14 ani Acestea se Întâlnesc la Catedrala din Făgăraş. Salut Făgăraș. Available online: http://salutfagaras.ro/de-300-de-ani-avem-cete-in-tara-fagarasului-de-14-ani-acestea-se-intalnesc-la-catedrala-din-fagaras/ (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Şinca Nouă a Găzduit a IX-a Ediţie a Festivalului Cetelor de Feciori. Salut Făgăraș. Available online: http://salutfagaras.ro/sinca-noua-a-gazduit-a-ix-a-editie-a-festivalului-cetelor-de-feciori/ (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Brunch în Veneţia Făgărașului. Vacanțe la Țară. Available online: https://www.vacantelatara.ro/brunch-in-venetia-fagarasului (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Muzeul de Panze si Povesti—Istoria Locului si Imagini din Interior. Available online: https://blog.mandrachic.ro/muzeul-de-panze-si-povesti-istoria-locului-si-imagini-din-interior/ (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Stănilă, I. Povestea de Succes a unui Brand Românesc: Atelierul-Şezătoare în Care se Reinventează Zestrea Românească. Available online: https://adevarul.ro/locale/calarasi/povestea-succes-unui-brand-romanesc-atelierul-sezatoare-reinventeaza-zestrea-romaneasca-1_588217f45ab6550cb89ef73c/index.html (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Cornilă, C. Lumină după 700 de ani de Istorie. Negru Vodă şi Cetatea de la Breaza ies din Naftalina Timpului. Salut Făgăraș. Available online: http://salutfagaras.ro/lumina-dupa-700-de-ani-de-istorie-negru-voda-si-cetatea-de-la-breaza-ies-din-naftalina-timpului/ (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- The World’s 10 Best Castles. Huffpost. Available online: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/the-worlds-ten-best-castles_b_5536786 (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Primăria Municipiului Făgăraș. Prezentare Generală. Available online: http://www.primaria-fagaras.ro/tara_fagarasului/detaliu/61 (accessed on 21 March 2022).

- Cioroianu, A. Pe umerii lui Marx. O Introducere în Istoria Comunismului Românesc; Curtea Veche: Bucharest, Romania, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrincu, D. Rezistenţa armată anticomunistă din Munţii Făgăraş—Versantul nordic.” Grupul carpatic făgărăşan”/Grupul Ion Gavrilă (1949/1950–1955/1956). Anuarul Institutului de Istorie «G. Bariţiu» din Cluj-Napoca 2007, XLVI, 433–502. [Google Scholar]

- Ciobanu, M. Remembering the Romanian Anti-Communist Armed Resistance: An Analysis of Local Lived Experience. Eurostudia 2015, 10, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Comisia Prezidenţială Pentru Analiza Dictaturii Comuniste din România. Raport Final. 2006. Available online: http://old.presidency.ro/static/rapoarte/Raport_final_CPADCR.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Sorea, D.; Bolborici, A.M. The Anti-Communist Resistance in the Făgăraș Mountains (Romania) as a Challenge for Social Memory and an Exercise of Critical Thinking. Sociológia-Slovak Sociol. Rev. 2021, 53, 266–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretero, M. The Teaching of Recent and Violent Conflicts as Challenges for History Education. In History Education and Conflict Transformation; Psaltis, C., Carretero, M., Čehajić-Clancy, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; pp. 341–377. [Google Scholar]

- Psaltis, C.; Carretero, M.; Čehajić-Clancy, S. Conflict Transformation and History Teaching: Social Psychological Theory and Its Contributions. In History Education and Conflict Transformation; Psaltis, C., Carretero, M., Čehajić-Clancy, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Schituri și Mănăstiri Ortodoxe. Available online: http://sostarafagarasului.ro/schituri-si-manastiri-ortodoxe/ (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Mănăstirea Dejani. Obiectiv Ortodox. Available online: https://obiectivortodox.wordpress.com/2011/06/21/manastirea-dejani/ (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Domeniu Schiabil în Munții Făgăraș. 150 Kilometri de pârtii. Salut Făgăraș. Available online: http://salutfagaras.ro/domeniu-schiabil-in-muntii-fagaras-150-kilometri-de-partii/ (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Csesznek, C.; Sorea, D. Communicating Intangible Cultural Heritage Online. A Case Study: Făgăraş Country’s Town Hall Official Websites. Rev. Română Sociol. 2021, XXXII, 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Sorea, D.; Borcoman, M.; Rățulea, G. Factors that Influence Students’ Attitude Towards Copying and Plagiarism. In Legal Practice and International Laws, Proceedings of the International Conference on Intellectual Property and Information Management (IPM ‘11), Brașov, Romania, 7–9 April 2011; Murzea, C.L., Repanovici, A., Eds.; WSEAS Press: Athens, Greece, 2011; pp. 315–318. [Google Scholar]

- Sorea, D.; Repanovici, A. Project-based learning and its contribution to avoid plagiarism of university students. Investig. Bibl. 2020, 34, 155–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorea, D.; Roșculeț, G.; Bolborici, A.-M. Readymade Solutions and Students’ Appetite for Plagiarism as Challenges for Online Learning. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borcoman, M.; Sorea, D. Final Year Undergraduate Students’ Representation of the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Lockdown: Adaptability and Responsibility. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strategia de Dezvoltare Locală GAL Microregiunea Valea Sâmbetei. Available online: http://galmvs.ro/wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Strategia-de-Dezvoltare-Locala-GAL-MVS-2014-2020.pdf (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Strategia de Dezvoltare Locala a Viitorului GAL Rasaritul Tarii Fagarasului. Available online: https://docplayer.ro/188927956-Strategia-de-dezvoltare-locala-a-viitorului-gal-rasaritul-tarii-fagarasului-cuprins.html (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Roșculet, G.; Sorea, D. Commons as Traditional Means of Sustainably Managing Forests and Pastures in Olt Land (Romania). Sustainability 2021, 13, 8012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proprietarii de Terenuri se opun Înfiinţării Parcului Naţional Făgăraş. Aceștia se tem că Parcul va afecta Grav Satele din Areal. Available online: http://fagarasultau.ro/2019/05/08/proprietarii-de-terenuri-se-opun-infiintarii-parcului-national-fagaras-acestia-se-tem-ca-parcul-va-afecta-grav-satele-din-areal/ (accessed on 21 November 2021).

- Sorea, D.; Roșculeț, G.; Rățulea, G.G. The Compossessorates in the Olt Land (Romania) as Sustainable Commons. Land 2022, 11, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nostra Silva. Federaţia Proprietarilor de Păduri şi Păşuni din România. Available online: https://www.nostrasilva.ro/ (accessed on 22 April 2022).

- Țara Făgărașului. Despre noi. Available online: https://tarafagarasului.com/despre-noi/ (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Țara Făgărașului. Descoperă. Available online: https://tarafagarasului.com/descopera/ (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Țara Făgărașului. Sugestii Pentru 7 zile de vis in Tara Fagarasului, Destinatia Anului 2020 in Romania. Available online: https://tarafagarasului.com/2020/07/30/destinatia-anului-2020/ (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Megeirhi, H.A.; Woosnam, K.M.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Ramkissoon, H.; Denley, T.J. Folosirea unui cadru de valori-credință-normă pentru a evalua intențiile locuitorilor Cartaginei de a sprijini turismul durabil al patrimoniului cultural. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 1351–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.M.; Ren, L. Qualitative analysis of residents’ generativity motivation and behaviour in heritage tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 124–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, F.; Popa, M. Organizaţiile colective ale proprietarilor de păduri. In Organizaţiile Colective ale Proprietarilor de Terenuri Agricole și Forestiere; Petrescu, C., Ed.; Polirom: Iași, Romania, 2013; pp. 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tomczewska-Popowycz, N.; Taras, V. The many names of “Roots tourism”: An integrative review of the terminology Journal Article. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 50, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wantzen, K.M.; Ballouche, A.; Longuet, I.; Bao, I.; Bocoum, H.; Cissé, L.; Chauhan, M.; Girard, P.; Gopal, B.; Kane, A.; et al. River Culture: An eco-social approach to mitigate the biological and cultural diversity crisis in riverscapes. Ecohydrol. Hydrobiol. 2016, 16, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Manzano, J.I.; Castro-Nuño, M.; Lopez-Valpuesta, L.; Álvaro Zarzoso, Á. Assessing the tourism attractiveness of World Heritage Sites: The case of Spain. J. Cult. Herit. 2021, 48, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oremusová, D.; Nemčíková, M.; Krogmann, A. Transformation of the Landscape in the Conditions of the Slovak Republic for Tourism. Land 2021, 10, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandić, A.; Kennell, J. Smart governance for heritage tourism destinations: Contextual factors and destination management organization perspectives. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 39, 100862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koens, K.; Melissen, F.; Mayer, I.; Aall, C. The Smart City Hospitality Framework: Creating a foundation for collaborative reflections on overtourism that support destination design. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 19, 100376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandić, A. Optimisation of tourism development in destinations: An approach used to alleviate the impacts of overtourism in the Mediterranean region. In Handbook for Sustainable Tourism Practitioners; Spenceley, A., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021; pp. 347–366. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, C.L. The role of government in the tourism sector in developing countries: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2020, 75, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coudounaris, D.N.; Sthapit, E. Antecedents of memorable tourism experience related to behavioral intentions. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 1084–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfi, S.; Hall, C.M.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M. Exploring memorable cultural tourism experiences. J. Herit. Tour. 2020, 15, 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastegar, R.; Seyfi, S.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M. How COVID-19 case fatality rates have shaped perceptions and travel intention? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Community | I1.1 | I1.2 | I2. 1 | I2.2 | I2.3 | I3 | ICH Categories | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Comăna | 647 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | SPRE |

| 2 | Hârseni | 608 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 46 | 14 | PAM, SPRE, TC |

| 3 | Hoghiz | 190 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | SPRE |

| 4 | Lisa | 27 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 2 | SPRE, TC |

| 5 | Părău | 240 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | SPRE |

| 6 | Sâmbăta de Sus | 313 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 3 | OTE, SPRE, TC, KNU |

| 7 | Şercaia | 3139 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 3 | OTE, PAM, SPRE, TC |

| 8 | Şinca | 452 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 3 | OTE; PAM, SPRE, TC |

| 9 | Şinca Nouă | 271 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 10 | PAM, SPRE, TC |

| 10 | Ucea | 19 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 31 | 3 | PAM, SPRE, TC |

| 11 | Viştea | 367 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | PAM, SPRE, TC |

| 12 | Voila | 239 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | SPRE |

| Tipe of Vision | ATUs | |

|---|---|---|

| a | Glocal vision | Comăna, Mândra, Părău, Șinca, Viștea |

| b | Dynamic local vision | Beclean, Drăguș, Voila, Șinca Nouă, Sâmbăta de Sus |

| c | Static local vision | Hârseni, Hoghiz, Lisa, Recea, Șercaia, Ucea |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sorea, D.; Csesznek, C.; Rățulea, G.G. The Culture-Centered Development Potential of Communities in Făgăraș Land (Romania). Land 2022, 11, 837. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11060837

Sorea D, Csesznek C, Rățulea GG. The Culture-Centered Development Potential of Communities in Făgăraș Land (Romania). Land. 2022; 11(6):837. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11060837

Chicago/Turabian StyleSorea, Daniela, Codrina Csesznek, and Gabriela Georgeta Rățulea. 2022. "The Culture-Centered Development Potential of Communities in Făgăraș Land (Romania)" Land 11, no. 6: 837. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11060837

APA StyleSorea, D., Csesznek, C., & Rățulea, G. G. (2022). The Culture-Centered Development Potential of Communities in Făgăraș Land (Romania). Land, 11(6), 837. https://doi.org/10.3390/land11060837