Abstract

Marinas are maritime features related to nautical tourism. The contemplation of pleasant surroundings acquires great importance in achieving this leisure character. The European Landscape Convention undertakes the necessity of integrating landscape into the planning policies. Thus, the marina’s management decision-making processes should reflect this awareness of the landscape. However, the landscape evaluation has not been appropriately considered despite its importance. This research attempts to introduce an initial framework to evaluate this influence, highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of the different subjects. For this purpose, the most significant elements of the marina management related to the landscape were rated, both from management and landscape perspectives. Two expert panels from Spain were used: 23 experts evaluated the above elements following the Delphi method, and 17 weighted the main management activities using DHP. Results show that there is a lack of concern for the landscape. Managers tend to consider physical conditions, whereas subjective conditions are relegated to the background. In this respect, this methodology provides the first stage for the landscape/management relationship, helping managers identify the main topics and prioritize related actions.

1. Introduction

Since the early 20th century, the management of marinas has sought a balance between the taxes on users and the provision of funds for the port infrastructures and services [1]. However, the cultural, social, and technical changes have led to new management approaches based on integrating infrastructure, processes, employees, and stakeholders to achieve mutual objectives [2]. Marinas are considered the most complex and highest-quality nautical ports, closely related to nautical tourism [3,4]. However, increased concerns for the environment and society are becoming a current pressure factor on marinas [5]. This pressure has enabled the introduction of new services grounded on local natural and spatial potential, and the surroundings’ broader needs to be met [6,7]. Marinas represent an opportunity to revitalize local communities [8]. In addition, ports may house architecture and heritage that reflect their sociocultural past [9]. Their landscape reflects the evolution of their activities and knowledge [10]. Nevertheless, marinas should also be considered a hospitality business with luxury amenities beyond their utilitarian services for vessels [11,12]. Hence, hard values (economic wealth, available services, etc.) and soft values (beauty, landscape, hospitality, etc.) coexist in port areas, which may lead to conflicts [7]. Moreover, it is not easy to achieve a balance. This makes management more complex than the balance between fee revenue, nautical services, and maintenance expenses. Although there is a vast literature on service management and marketing, strategic models adapted to marinas are lacking [13]. This deficiency leaves marina managers with no relevant academic guidelines, which can be framed within the general lack of formal academic attention to marinas [12].

The landscape results from the mutual action between human and natural factors [10,14]. The European Landscape Convention (ELC) highlights that the landscape contributes to human well-being and is a vital economic resource in globalization. It also undertakes the necessity to integrate landscape into the planning policies [15]. There is a growing concern about improving the understanding of landscape, culture, and socio-ecological linkages therein [16]. The landscape is related to social, economic, and environmental values as it incorporates intangible aspects and interrelationships between human communities and their environment [17].

Due to the interconnection between society, leisure, economic growth, and the sea and coast, marinas recognize the role of the landscape in developing effective marina management. Moreover, this landscape is a factor in the quality of the environment, including topics related to visitors’ perceptions, such as a salty taste, the sound of water or the feeling of the wind [18], water quality [19], or a coastline’s physical conditions [20]. A pleasant environment and scenic views allow marinas to provide leisure and gain economic benefits [21]. Moreover, open and well-arranged public spaces transmit well-being and safety perceptions [22]. Managers may also improve business by communicating their image, providing a character, and helping to link to the local territory [23]. Furthermore, the landscape represents tourism’s keystone and driving force [24]. Therefore, the landscape within marinas increases the intangible values and services provided to users [25], enhancing the hospitality and the benefit. Thus, the basic assumption that the landscape improves marina management requires tools that allow its inclusion in decision-making processes. Nevertheless, as a first stage, any procedure should be grounded on an analysis of what marina managers understand as a landscape within marina management.

How the concept of landscape has been approached in marinas has varied over time. The first stage to address this question is usually the approach from the aesthetic point of view because the concern for beauty has a strong relationship with the landscape [26]. Furthermore, the visually pleasant environments can attract people, creating an atmosphere of activity that enhances the setting [27]. Some studies indicate a pleasant and harmonic, balanced environment is an attractive stimulus for future users of marinas [28,29,30]. Other authors remark that accessibility to the water’s edge is essential in shaping recreational and aesthetic values [27,31,32]. Roff [27] identifies four elements that lure spectators to the marina. Blain [33] emphasizes the attention paid to local architecture in marinas, considering the public’s needs. Raviv et al. [13] underline the landscape observed from/on the way to a marina as a strategic factor affecting its occupancy. Girard [34] points out various aspects related to the beauty of ports. Trisutomo [35] summarizes the visual objects for coastal cruise tourism. Martín and Yepes [19] define the marinas’ landscape elements, rating them within three hierarchical stages (territorial, local, and inner levels). Therefore, the landscape in marinas has changed from a mere aesthetic attribute to a set of elements related to management and their environment.

Despite the wide range of landscape management that has been documented by scholars in the marine [36,37,38] and coastal sectors [39,40,41], little research effort seems to have focused on how to approach the landscape within marinas’ management. Martín and Yepes [42] identify the elements of the marinas’ landscape that may be significant in their management, but the study does not go further. Marina managers face a double challenge when tackling landscape management: first, a related element can sometimes be ambiguous and indeterminate; second, it is necessary to know how to incorporate these elements into the management.

The aim of this paper is to provide an appreciation of how marina managers perceive the landscape within marinas. In the previous related studies, the elements that constituted the landscape in marinas were analyzed. The novelty of this study regards the application of the Delphi survey and AHP methods to collect the opinion of Spanish marina managers. For this purpose, we dealt with the assessment of port management activities and with certain aspects of marina management elements related to the landscape. The research questions (RQ) of this study were as follows:

RQ1. How is the landscape understood in the marina by managers? The most significant elements in managing the marinas related to the landscape are rated both from a managing and landscape viewpoint. The comparison and analysis of both scores will help to answer this question.

RQ2. How can management transform the perception of the landscape? Qualitative weights were introduced for the rates mentioned above. These new factors may introduce variations in the valuation of the elements that reflect the proper appreciation of the landscape within the management of marinas.

The Delphi method and Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP) were used to explore the landscape and management in the current study. This reflects an impulse to go beyond the rhetoric of the ELC and implement the landscape more strongly in the marina’s management arena. It provides managers of marinas with a tool to deal with an intangible element such as the landscape. It may also allow the incorporation of consideration of the landscape within decision-making processes.

2. Research Process

2.1. Methodology

The Delphi survey and Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) were used in this work as the basis for the methodological approach for this study. The Delphi survey was adopted to rate a set of elements related to the management of marinas, both from a management and landscape point of view. The Delphi survey is a method introduced by the Rand Corporation in 1950, and, since then, it has been used for multiple investigations [43,44,45]. It is a structured and systematic group communication process technique used to deal with a complex problem. It is based on the basic assumption that estimations and assessments from a structured group are more accurate than those from unstructured ones. For this purpose, a group of separate experts on a particular topic undergoes multiple iterations to enable the achievement of a consensus by iterative rounds of progressive blind feedback concerning the overall group opinion. It allows for adjusting the responses and reducing the bias. However, the final goal is not necessarily to achieve a consensus, but rather to assess the statement from the issues’ context [46]. The Delphi survey has been used for landscape studies [47,48], including those of the coastal landscape [49] and marina landscape [19].

The second method used the AHP method. AHP is a general theory for measuring objectives and intangibles to solve multicriteria decision making through pairwise comparisons. It derives preference scales concerning criteria or alternatives that make up the problem for a defined objective. The AHP method is used to obtain the best alternative from a given set that best satisfies the established criteria, or to obtain priorities for the alternatives by establishing ratings for each criterion and prioritizing them by pairwise comparison or preferences. For this purpose, the scale of comparison of elements between the alternatives at each level of the hierarchy is used to obtain relative weights. Each weight represents the strength of the compared element relative to the others [50]. AHP has been widely adopted by academics in multiples studies [51,52,53]. Although AHP has been applied to commercial ports [54,55], there is a lack of application in the management of marinas [56].

This study adopted the Delphic Hierarchy Process (DHP) as the second methodological approach. This method was used to reflect the relative strength of preferences in managing activities. Its methodological justification is grounded on the fact that combining the Delhi method with others is valuable, either improving its analytical skills or contributing as an input to other methods [57]. The DHP theory combines the Delphi method and the Analytical Hierarchy Process (AHP): the steps of the AHP are adopted by gathering the opinion of the experts through the Delphi method [58].

2.2. Selection of Participants

The selection of the participants influences the reliability of the results obtained from the Delphi survey [59]. We used two groups of experts depending on the subject matter: landscape marina and marina management. We selected the panelists within the Spanish context.

In the first group, integrating cross-functional and interdisciplinary knowledge positively influenced cognitive biases [60]. The Delphi survey was used to gather theoretical and practical knowledge and experience. As a target group, we considered experts from consulting companies, academia, and management areas. A number between 15 and 20 respondents was appropriate [19]. We sent more than 100 invitations by email to Spanish experts. This included a description of the study, the primary goals, the methodology used, and the required requirements. We also asked whether they knew other experts who might be interested in participating. Overall, 26 people agreed to participate, but only 24 met the requirements: academics (30.4%), consulting companies (20.1%), and managers (49.5%). Implementing an online self-survey assessed the compliance of at least four of the eight requirements. In some cases, telephone contact was used to clarify specific issues. Although the composition of the panelists was the same as that used for a previous survey [19], the content was different, as shown in the questionnaire development.

The second group tackled the main activities associated with marina management. We established a conventional expert-oriented panel to achieve a reliable consensus on the focus. While the Delphi survey was used to confirm the main activities related to marina management, the DHP method settled relative weighting. We adopted the same criteria mentioned above to determine the number of respondents. The only requirement established was to have experience in the management of marinas. More than 180 emails were sent to managers, planners, and designers of marinas in Spain, including a description of the survey, the primary targets, and the applicable methodology. Finally, 19 agreed to participate, with a final count of 17 respondents.

2.3. Questionnaire Development and Survey

Traditionally, one of the characteristics of the first round of the Delphi method is the exploration of the topics under discussion, in which each individual contributes within an open-ended questionnaire [56]. However, most studies begin with a literature review to provide an initial set of themes that immediately enable the panelist to focus on the subject matter [19]. In this case, we used a structured questionnaire based on a literature review and a series of open-ended questions. It is necessary to consider the outputs obtained from the confrontation of the most significant management elements with those of the landscape in marinas. The subjects considered were based on the study carried out by Martín and Yepes [42]. They analyzed the topics related to marina and landscape management, taking into account physical (visibility) and subjective (judgments) aspects. A bar graph for each parameter was included in the subsequent rounds, providing the practitioner with understandable background information. A 5-point Likert-type scale assessed the importance of the landscape elements within the management items. A three-round online Delphi survey was used.

In a second step, we attempted to achieve a twofold aim: to validate the main marinas’ management activities, and to obtain the pairwise comparison matrix for the validated activities. The groups of activities of marinas’ management considered were: (1) services; (2) financial feasibility; (3) environmental management; and (4) maintenance. The types of processes that make up the management of public spaces support these sets [42,61]. Thus, we derived two questionnaires. The first was a two-round Delphi survey developed for the evaluation of the abovementioned activities. We used a 7-point Likert-type scale to provide a more accurate result. Secondly, we attempted to establish the relative weights of the four activities considered through a DHP survey. With this aim, we prepared a pairwise comparison to obtain priorities for the criteria by judging their relative importance in pairs. A two-round Delphi survey collected the AHP opinions. We adopted the geometric mean of each valued judgment provided by the panelists as the final value adopted for each activity.

Due to the need for several rounds of surveys, online questionnaires were determined as the most effective data collection method. Nevertheless, the authors sent several emails to the participants to remind them of their participation. The questionnaires were subsequently tabled in consultation with three experts in the management of marinas having more than ten years of experience, who reviewed and improved them.

2.4. Data Analysis

The Delphi method aims to collect judgments on a given topic based on providing summary information and feedback of opinions from previous responses [46]. The convergence of the answers increases with the number of rounds. It is observed that a point of diminishing returns is reached after a few rounds. Commonly, stability in response is usually achieved in the third round, but there is no standard technique for evaluating the consensus level [62]. Holey et al. [63] suggest three ways to determine the agreement: (a) the aggregate of judgments, (b) a move to central tendency, and (c) stability.

Decision rules were established to gather and organize the judgments and insights provided by participants of the Delphi method. To enable statistical analysis, the questionnaires were based on a Likert-type scale. We used a 5-point scale for the marina landscape and a 7-point scale for the marina management activities. The first rated the influence of the elements within the landscape of marinas through the following options: negligible (1), low (2), moderate (3), remarkable (4), or high (5). The second considered the ratings of the importance within the management of marinas, valuing the relevance using the following scale: insignificant (1), scarce (2), low (3), moderate (4), remarkable (5), high (6), or extreme (7). The significant statistics used in the Delphi method are measures of central tendency and the level of dispersion [64]. Thus, descriptive statistics of the ratings considered were as follows: rating median (Md), standard deviation (SD), and quartile deviation (IQR). Based on those mentioned above, the rules adopted to analyze the validity of the consensus reached for an item were: (a) rating by over 50%; (b) rating mean (Md) ≥ 3.5 (5-point Liker scale) or ≥4.5 (7-point Liker scale); and (c) IQR ≤ 1.0.

DHP was undertaken for the Delphi survey to arrange a pairwise comparison matrix for objectives, establishing priorities for criteria by judging them in pairs for their relative importance. The judgments were represented by the number from graduation for quantitative comparison of alternatives: equal importance (1), moderate importance (3), strong importance (5), very strong or demonstrated importance (7), extreme importance (9), or intermediate values between two adjacent judgments to reflect fuzzy inputs (2, 4, 6, 8). A value of Kendall’s W obtained for Md average value greater than 0.5 was used as an indicator of stopping rounds. It was necessary to determine the consistency of the experts’ judgments, to avoid contradictions or biases. The AHP method applies the consistency ratio (CR) to measure individual inconsistency. This ratio was calculated for each response, discarding those with a value greater than 0.09 [50]. The eigenvector of each valid matrix was obtained. The methodology proposed by Aznar and Guijarro [65] was used to determine the eigenvalues, which represent the priority among objectives. The final values considered were obtained as the geometric mean. Appendix B shows the results of the application of the DHP method, including those corresponding to the Delphi survey, and those related to the AHP method.

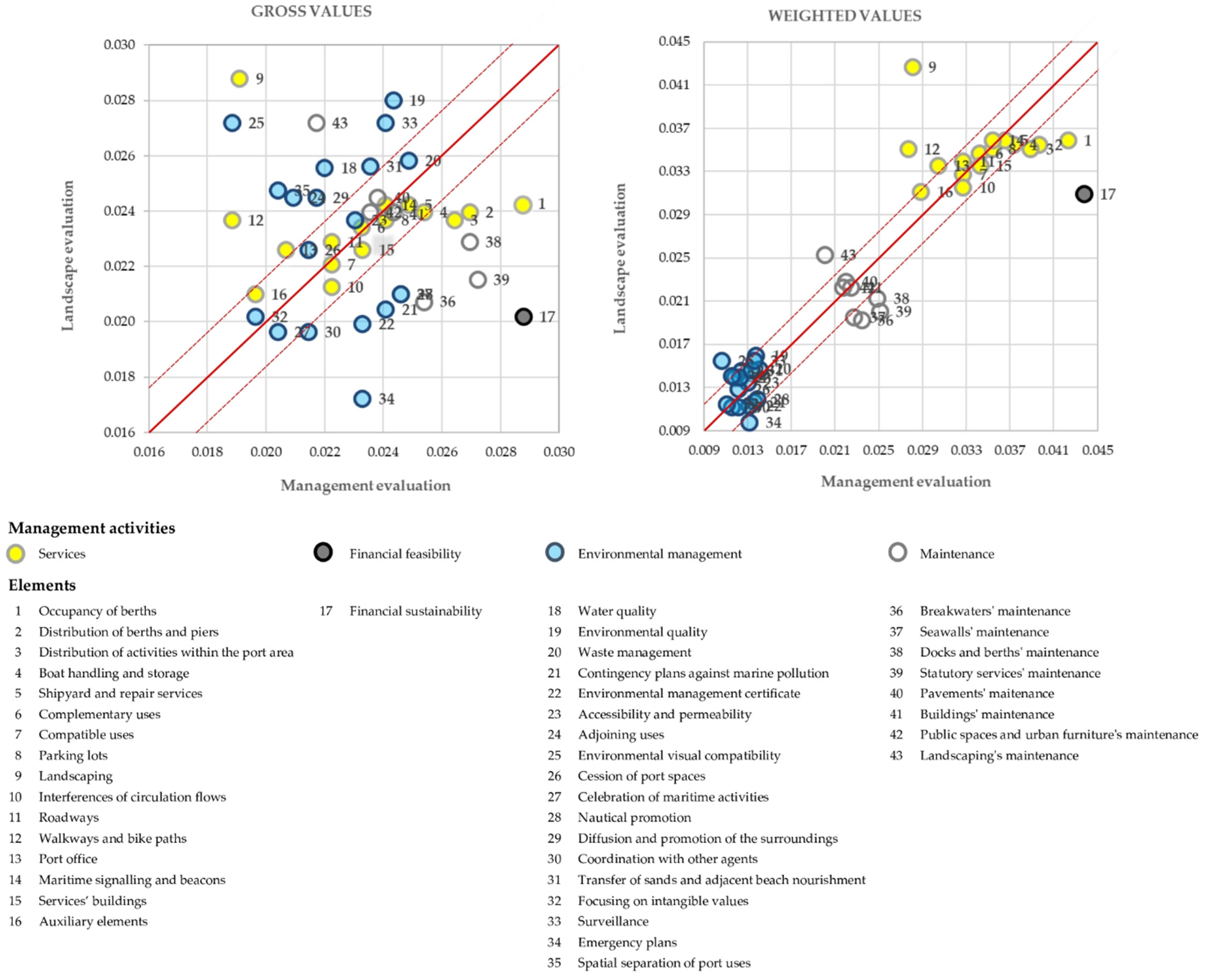

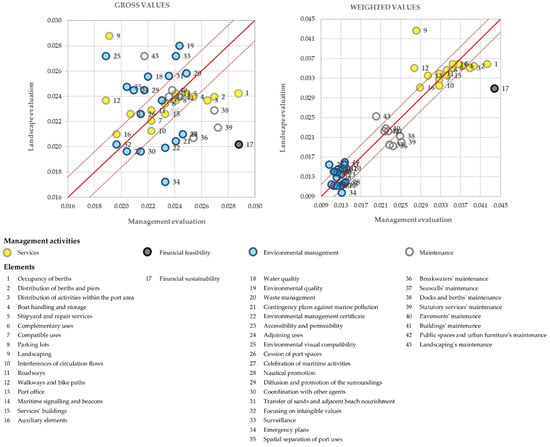

Once the processing of the data resulting from the first survey was completed, the valuation data of the elements related to the marina were obtained from the perspective of management and landscape. These represent the gross values. Furthermore, the weighting coefficients of the management activities were obtained through the DHP. We obtained the weighted values by applying the corresponding coefficient to each group of elements according to the activity considered. All the values (gross and weighted) were normalized between 0 and 1.

3. Results

If we focus on the first survey, there was no significant difference between those who started the Delphi survey and those who completed it. Twenty-three of the twenty-four initial participants finished the whole round (95.8% overall initial participants), rating 43 elements. Two of them were added to the open-ended question suggested by the participants. Table A1 and Table A2 from Appendix A display the statistics obtained for each round (mean value, SD, Q, and percentage of agreement).

All the elements included were validated as they reached a cumulative percentage of more than 50% for a score equal to or greater than 3. However, if we had considered a more restricted condition, there would have been slight variations. Responses to the second round were received from 23 participants. In this round, and focusing on the management of the marina, 62.8% of the items complied with all of the requirements for consensus. The primary defect was not reaching the minimum 50% threshold. Regarding the marinas’ landscape, 63.8% of the elements did not achieve total consensus among experts. The leading cause was divided between dispersion and low threshold. Hence, a third-round questionnaire was needed. After this new round, there was no consensus on 17 elements related to the management of marinas and 16 corresponding to the landscape of marinas. The major failure was not achieving 50% for all items, although most of them exceeded 40%. Nevertheless, it must be said that not achieving consensus does not mean invalidity of an item, but that there is no total agreement between all participants. First, the ambiguity of the concept of the landscape can be approached from different areas of knowledge. This may lead to confusion in the interpretation. Second, the associated subjectivity may be a problem, as consensus among experts is weak on specific issues based on the variety of maritime infrastructures and their experience.

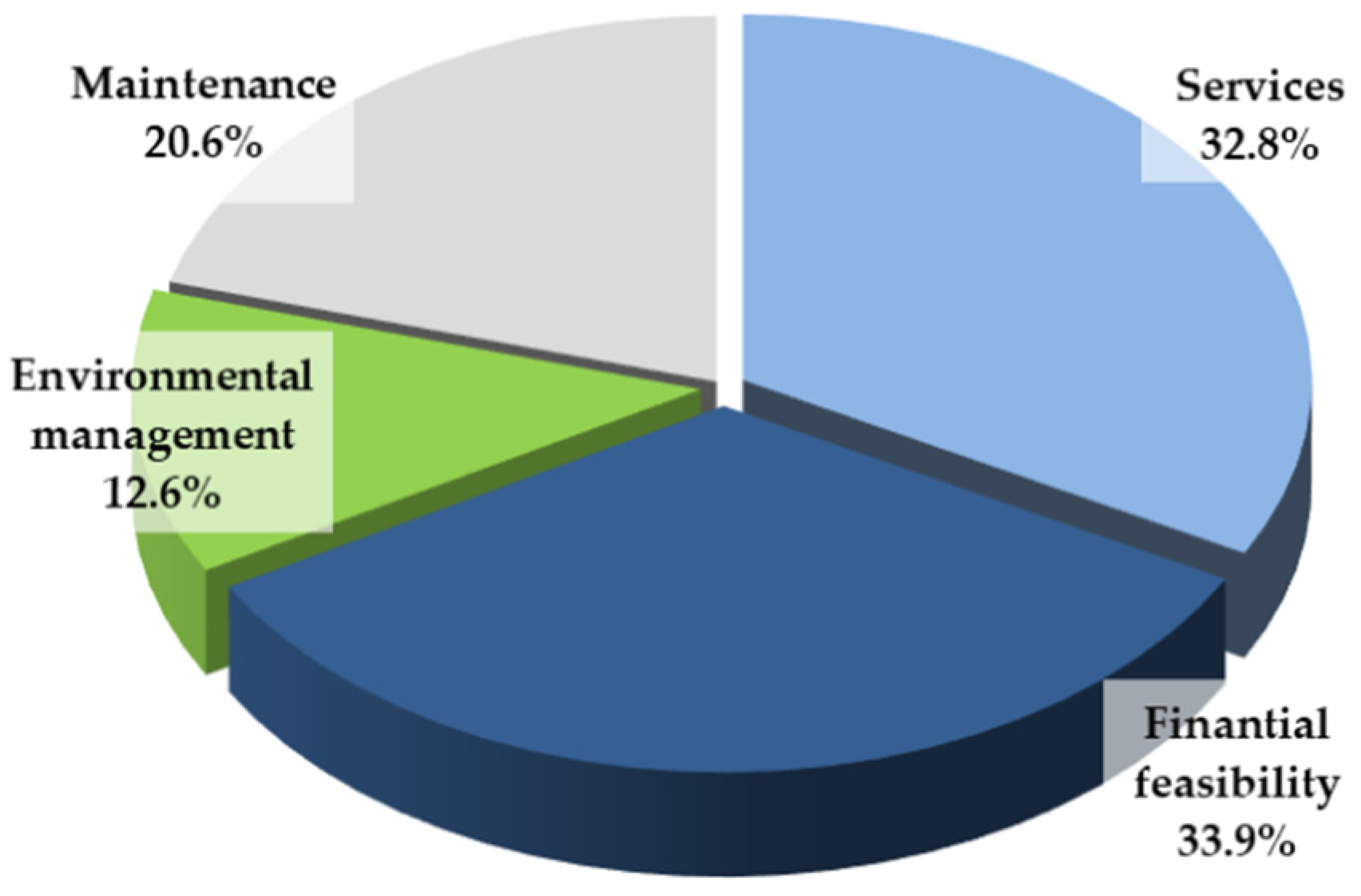

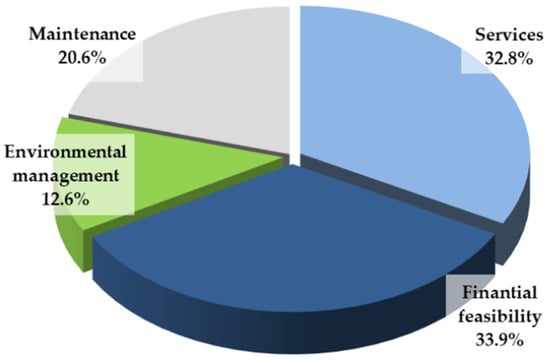

In a second step, the weighted values helped determine weak and strong attributes, and their ranking. For this, the DHP highlighted the different abovementioned elements selected by the experts, providing the weighted coefficient to qualify the four activities considered. For this purpose, two surveys were carried out, which initially counted 19 participants, of whom, 17 completed the surveys (89.5%). The first was a two-round Delphi survey. It served to validate the four proposed activities. All of them were accepted because they complied with the requirement for consensus (Table A3). The second round stopped the survey because Kendall’s W showed the maximum value for Md average among rounds (W = 0.906). The second survey was a peer comparison in a two-round DHP. Of the 17 matrices obtained, 12 were rejected because they exceeded the threshold established for the consistency ratio (CR ≤ 0.09). This represents a rejection of 70.6% of the experts’ judgments as inconsistencies. The weighted values determined are shown in Figure 1 and Table A4.

Figure 1.

Weighted values for management activity obtained from the pairwise comparison (DHP survey).

4. Discussion

In general, this study provided insights for marina managers who aim to enhance the landscape in the decision-making process of marina management. The awareness of the landscape may be a competitive advantage, leading managers to consider it. The rating framework represents the practical outcome of the study. In an orderly manner, it shows the most significant elements in the management of marinas and their rating from the point of view of the landscape. It allows managers of marinas to check whether decisions will have more or less influence on the marina landscape to act appropriately. Moreover, it mirrors how the landscape is perceived in the marina. The gross value analysis responds to RQ1, whereas the weighted analysis represents the basis for responding to RQ2. In addition, the comparison between gross and weighted values also reinforces RQ2.

Nevertheless, it is essential to point out the high inconsistency of the AHP survey outputs among marina managers. This may be a result of disinterest in conducting the survey. However, it may also reflect the need to organize training courses for marina staff, including thematic blocks in management and operational positions [66].

The rating framework confirmed that “Financial feasibility” (0.3394), closely followed by “Service” (0.3283), were the most important activities within management. “Environmental management” was the least important management activity for most valid respondents (0.1262). These weights applied to the raw values were used for the rating variations of the elements of each group, widening the differences concerning the initial ratings; that is, the introduction of group priorities clarified the individual scores. Table 1 lists the total ratings, and Figure 2 visually represents the differences.

Table 1.

Ranking framework of management and landscape in marinas.

Figure 2.

Rating framework, gross values.

The first way to approach the analysis is through the scores obtained. Firstly, “Occupancy of berths” and “Economic sustainability” were the main elements from a managing perspective. They were followed by “Statutory services’ maintenance”, “Docks and berths’ maintenance”, and “Distribution of berths and piers”. These scores were relatively in line with the weighting of the activities. As discussed above, the central management activities were “Financial feasibility” and “Services”. However, there is a bias of services towards vessels (berths, docks, and statutory services), incorporating the maintenance of their excellent condition. At the other end of the scale, the least valued elements were “Environmental visual compatibility”, “Walkways and bike paths”, and “Landscaping”. This denotes a lack of sensitivity in management to any issue outside the service to vessels. It is also in line with the minimal valuation given to the activity “Environmental management”. Secondly, “Landscaping” and “Environmental quality” received the highest scores from a landscape viewpoint. This result is related to how managers perceive landscape. These are two elements that are more related to the concept of nature. Despite the relationship between humans and their surroundings, there is a tendency to consider only the natural part of the landscape without considering the human component of the environment. If the weightings were applied, the most important element in management was “Financial feasibility”, followed by all those associated with the “Services” group. The least valued were those associated with the “Environmental management” group.

The marina must offer a high level of service to boats and users. In this sense, the variety and quality of the services provided by the marina are a selection factor, with a positive correlation between them and the occupancy and satisfaction. Boaters’ satisfaction is a key indicator of the quality of the marina service provided [10,11]. Furthermore, managers’ goal is to achieve an appropriate means of ensuring higher profit with lower cost. In this sense, boaters’ attraction could not be grounded in higher-quality infrastructure. The current challenges of marinas, including spatial limitations, financial, social, and environmental constraints, and sustainability, require a more complex management system [67]. In this sense, there is a bias in the management activities’ perception of respondents since environmental protection represents a main element in it [68]. Marinas should be seen as the gateway to coastal areas, sustainably interlinking the economy and local development [4,69].

The analysis of the level of dichotomy is the second approach that could be used. Figure 2 represents the pairwise comparison for the different elements, considering the landscape and the managing perspective (gross and weighted values). We distinguished three groups of topics (Table A5). The first comprises those subjects whose management is more important than landscape. This group encompasses the traditional activities carried out within the marina: boat-related and financial feasibility. The second is made up of those that are more important from the perspective of the landscape. Finally, the third group corresponds to those subjects that balance management and landscape. They are characterized by economic income sources and their significant visual impact. Also in this group are those questions related to the port–city relationship. Considering the three groups mentioned above, the validity of this assumption was analyzed by employing discriminant analysis, which showed a significance of less than 0.005. Appendix C reflects the sets considered and the main outputs from the discriminant analysis carried out.

Despite the low levels of landscape awareness, some issues are considered related to the first group. Providing services is the cornerstone of every marina in terms of its economic justification and nature [67,70]. Moreover, a marina is a form of maritime infrastructure that responds to a need that is lacking in the natural environment, specifically, a sheltered area for boats. These shortcomings are alleviated by transforming the natural processes using technology [71]. The absence of boats in a marina does not provide a justification for needing such infrastructure, by destroying the existing landscape and leading to social rejection [10]. Small craft and sailing boats are the raison d’être of all marinas, and identify and configure them. The piers and pontoons are distributed on the water’s surfaces according to the characteristics of the boats and their maneuverability. Furthermore, this distribution determines the amount of the surface of water that can be seen. Thus, viewpoints will be more suitable where the dock is wide enough to allow a vision of an extensive water surface or where the mooring lines are located at a minor angle, rather than in the direction of vision. The sight of land is addressed through urban landscape studies [72,73], where paths, districts, and landmarks can be identified within the marina [23].

The second group is concerned with obtaining an image of the marina. There are marine-related facilities that are easily identifiable and associated with them and represent an identity [19,74]. As Adie [30] highlights, apart from development as a response to the sailing needs, visual amenity and facility form one of the nuclei from which marinas may grow. If this image is unique or singular, it leads to an own identity [65]. Landscape identity is related to the spatial and physical features, as the pattern of elements, making it recognizable [14]. The recognition of the image of a marina represents a competitive advantage [23]. However, several studies point beyond the mere character of the landscape as a recognizable element, intending to enhance the engagement between people and the environment [75,76]. This may consider the risk of copying an existing concept when searching for an identity. Due to the repetition of a solution, the landscape lacks content. It is like a thematic space whose sole purpose is to perpetuate an image [77]. These are vacuous spaces that are unrelated to the cultural values of their environment. They are alien to the place where they are located, without linkage to meaning or representation. They are not consumer-oriented meeting places but their image. Moreover, security is considered a hospitality service quality item for marinas [78]

Finally, the third group is characterized by its dimensions, both physically and immaterially. The physical features—such as shipyards, boat handling and storage, service buildings, or auxiliary elements—comprise ancillary services, for both boats and seafarers. They are spaces of a certain extent, with significant visual impact, which also may represent a space of opportunity. Safety constraints associated with marinas’ management make it difficult to implement the landscape dimension. Nevertheless, this set can be focused on various approaches: (1) using techniques to reduce the visual impacts, such as surfaces treatment, landscaping, fences, or walls [27]; (2) not trying to hide but highlighting the potential of the port characteristics of these facilities that are easily identifiable [75]; or (3) a combination of both. The immaterial factors are issues related to a port–city relationship, which should be addressed from the spatial planning perspective [78]. It should include strategies and targets, starting from a mutual understanding of the respective requirements and needs, and a shared policy negotiation [34]. Complementary and compatible uses may help to improve the linkage with the surroundings, acting as transitional elements between the strictly urban uses and the port uses, thereby making them compatible with urban life [79]. Effective landscape management within marinas may materialize in an optimal distribution of the public uses, which may provide new recreational spaces for the urban core. These spaces offer a positive social impact for people to conduct recreational activities and as a social environment that can improve interaction [80]. Moreover, marinas used to be located close to city cores, and there should be spaces serving as a transition that enhances the link between the urban and the port uses [79].

Despite the concern for the visual aspect in the marina management, there is a lack of knowledge about the concept of landscape and its complexity. The ratings obtained mirror the very low concerns about the subjective conditions when the relationship between people and the environment is relegated to the background. This relation indicates a real need to foster and enhance landscape knowledge. A key point in this understanding must be how people perceive this space, and the perception that it feels like something of their own. An empty or available area may be filled with intangible elements, i.e., cultural practices [81] or strong character [82,83]. “Space” comes to be “place” when the set of relations between values and meanings are attached, thereby determining a sense of unity and wholeness [80]. Therefore, the mere physical vision becomes a landscape [42]. The subjective perceptions may enhance the links between people and places [84]. It also should be taken into account that marinas are places where it is possible to create social ties through common feelings and sharing of experiences [32]. These ties lead to an emotional attachment, which allows positive emotional responses in users, improving their well-being [85]. This response represents an opportunity for the marina as a binder of these ties, strengthening them and winning and retaining customers by offering superior values and services compared to competitors.

Despite our concerted effort, we found three main problems during the development of the surveys. The first difficulty was finding professionals who wanted to be involved (less than 20% of participants of the total number of emails sent). It is difficult to find people with knowledge of the marinas and landscape management, but it is harder to seek their involvement in the survey. The reliability of the results is higher with the increase in the number of participants [62]. Secondly, more training on landscape issues was needed to ensure the responses to the questionnaire were clear and not open to misinterpretation. Finally, performing too many rounds caused fatigue in the respondents [86], and we failed to include more valued items that may have improved the accuracy of the data. Including a set of intermediate levels of grouping should allow the identification of other priorities that would increase the accuracy of the influence of management.

5. Conclusions

This study analyzed how the landscape dimension is evaluated within the marina’s management, providing a practical framework to consider the significance of landscape in the various subjects related to management. The control and organization require an in-depth knowledge of the multiple components that comprise this management. The landscape is an element that may allow a pleasant atmosphere, and achieving an own character in a marina may improve business. Moreover, it is an indirect way to deal with hospitality. The set of tangible and intangible items and a friendly space to stay and share experiences is related. It indicates the landscape dimension should be considered early in decision-making processes.

Assigning value and importance is the lynchpin of management. This study provided a snapshot of general knowledge, valuating the theoretical findings of marina management. The consideration of management activities introduces weightings that increase the differences between the valuations initially obtained. Management activities have focused on economic and service provision issues, leaving behind other important issues if a broader vision is considered. Marina management should understand the mutual benefit of the port with its surroundings at an economic, social, environmental, and sustainability level. Moreover, the various subjects to be considered in each case may vary, and they should be adapted appropriately to the reality of each marina. Its configurations, location, and own constraints constitute the reality of its management.

Managers’ perception of the landscape in marinas focuses on visual aspects. The landscape is considered to be similar to nature in all regards. It implies a lack of understanding of the concept of the landscape. It is incomplete because it leaves behind all the subjective issues, personal sensations, and relationships with the environment. It is necessary to make an effort in landscape education in order to understand the complexity of the landscape and to be able to make an adequate assessment. Only with this knowledge will it be possible to integrate the landscape into management.

The marina landscape differs from the general approach presented, with its consequent impact on the ratings obtained. In this regard, the following should be considered for further research: (a) The themes exposed in the surveys may be general, and they can result in misunderstandings or biased interpretations. A better knowledge of the particular problem of the marina entails a better approach to the parameters to be evaluated. (b) It is necessary to consider the different features existing in the ports and their influence on the management. (c) The introduction of more hierarchical or network levels of decision, such as categories, would have an impact on a more accurate assessment.

An accurate understanding of the landscape dimension in marinas also requires an effort through the training of professionals and its consideration from the first stage in designing and applying management policies. When there is a shift to soft values in the marina’s management [9,39], understanding that the landscape entails individual and social well-being, rather than just a physical space, is a precondition for sustainable development. It should also be regarded as a crucial resource to enhance economic activity [87].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M. and V.Y.; methodology, R.M. and V.Y.; software, R.M.; validation, R.M. and V.Y.; formal analysis, R.M.; resources, V.Y.; data curation, R.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M.; writing—review and editing, R.M. and V.Y.; visualization, R.M.; supervision, V.Y.; project administration, V.Y.; funding acquisition, V.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación grant number PID2020-117056RB-I00.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Grant PID2020-117056RB-I00 funded by MCIN/AEI/ 10.13039/501100011033 and by “ERDF A way of making Europe”. We would like to thank all those professionals who agreed to participate in the Delphi and DHP surveys. This study would not have been possible without the contribution of their time, effort, and knowledge. We are also grateful to Manuel Ollero, Rafael Bordons, and Fernando Copado for agreeing to be part of the focus group and contribute their visions and opinions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

This appendix contains the final results for the three-round Delphi survey. The first column shows the main activities related to marina management. For each activity, the second column develops the elements considered for rating. Table A1 indicates the results related to the management viewpoint and Table A2 reveals the results related to landscape evaluation. The results and statistics obtained for each round are shown in both cases.

Table A1.

Statistical results from rounds related to management of marinas (Delphi survey).

Table A1.

Statistical results from rounds related to management of marinas (Delphi survey).

| Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity | Subject | P (x ≥ 3) | Md | SD | Q | % | Md | SD | Q | % | Md | SD | Q | % |

| Services | Occupancy of berths | 95.7 | 4.6 | 0.73 | 1 | 65.2 | 4.8 | 0.52 | 0 | 82.6 | 4.8 | 0.52 | 0 | 82.6 |

| Distribution of berths and piers | 100.0 | 4.2 | 0.60 | 1 | 60.9 | 3.6 | 0.59 | 1 | 60.9 | 4.5 | 0.51 | 1 | 52.2 | |

| Distribution of activities within the port area | 100.0 | 4.5 | 0.73 | 1 | 26.1 | 4.5 | 0.59 | 1 | 56.5 | 4.4 | 0.50 | 1 | 60.9 | |

| Boat handling and storage | 100.0 | 4.3 | 0.69 | 1 | 47.8 | 4.0 | 0.56 | 0 | 69.6 | 4.2 | 0.60 | 1 | 60.9 | |

| Shipyard and repair services | 100.0 | 4.1 | 0.73 | 1 | 47.8 | 4.0 | 0.71 | 1 | 52.2 | 4.1 | 0.69 | 1 | 52.2 | |

| Complementary uses | 100.0 | 3.9 | 0.90 | 2 | 21.7 | 3.7 | 0.63 | 1 | 52.2 | 3.7 | 1.06 | 1 | 50.0 | |

| Compatible uses | 95.7 | 3.8 | 0.98 | 2 | 39.1 | 3.7 | 0.70 | 1 | 43.5 | 3.7 | 0.88 | 1 | 52.2 | |

| Parking lots | 100.0 | 4.1 | 0.67 | 1 | 56.5 | 4.0 | 0.82 | 2 | 34.8 | 4.0 | 0.67 | 0 | 56.5 | |

| Landscaping | 95.7 | 3.3 | 0.69 | 0 | 73.9 | 3.3 | 0.56 | 1 | 73.9 | 3.2 | 0.65 | 1 | 69.6 | |

| Interferences of circulation flows | 100.0 | 4.0 | 0.74 | 2 | 47.8 | 3.9 | 0.63 | 1 | 60.9 | 3.7 | 0.63 | 1 | 52.2 | |

| Roadways | 100.0 | 3.7 | 0.62 | 1 | 56.5 | 3.9 | 0.69 | 1 | 52.2 | 3.7 | 0.63 | 1 | 52.2 | |

| Walkways and bike paths | 100.0 | 3.4 | 0.58 | 1 | 65.2 | 3.2 | 0.39 | 0 | 82.6 | 3.1 | 0.34 | 0 | 87.0 | |

| Port office | 95.7 | 3.8 | 0.95 | 1 | 43.5 | 3.8 | 0.67 | 1 | 52.2 | 3.4 | 0.99 | 1 | 39.1 | |

| Maritime signaling and beacons | 95.7 | 3.9 | 1.00 | 2 | 39.1 | 3.8 | 0.83 | 2 | 30.4 | 4.0 | 0.74 | 2 | 47.8 | |

| Services’ buildings | 95.7 | 3.9 | 0.95 | 2 | 47.8 | 3.8 | 0.65 | 1 | 56.5 | 3.9 | 0.63 | 1 | 60.9 | |

| Auxiliary elements | 100.0 | 3.4 | 0.59 | 1 | 60.9 | 3.4 | 0.90 | 1 | 56.5 | 3.3 | 0.45 | 1 | 73.9 | |

| Financial feasibility | Economic sustainability | 100.0 | 4.7 | 0.65 | 1 | 73.8 | 4.8 | 0.52 | 0 | 82.6 | 4.8 | 0.52 | 0 | 82.6 |

| Environmental | Water quality | 95.7 | 4.0 | 1.04 | 2 | 30.4 | 4.0 | 0.80 | 2 | 39.1 | 3.7 | 0.71 | 1 | 39.1 |

| management | Environmental quality | 100.0 | 4.3 | 0.81 | 2 | 34.8 | 4.1 | 0.69 | 1 | 52.2 | 4.0 | 0.64 | 0 | 60.9 |

| Waste management | 100.0 | 4.0 | 0.85 | 2 | 30.4 | 4.2 | 0.58 | 1 | 65.2 | 4.1 | 0.55 | 0 | 69.6 | |

| Contingency plans against marine pollution | 100.0 | 4.1 | 0.76 | 1 | 43.5 | 4.1 | 0.76 | 1 | 43.5 | 4.0 | 1.04 | 2 | 30.4 | |

| Environmental management certificate | 95.7 | 3.7 | 0.90 | 1 | 39.1 | 3.7 | 0.63 | 1 | 52.2 | 3.9 | 0.81 | 0 | 69.6 | |

| Accessibility and permeability | 100.0 | 3.6 | 0.58 | 1 | 52.2 | 3.9 | 0.73 | 1 | 47.8 | 3.8 | 0.72 | 1 | 47.8 | |

| Adjoining uses | 100.0 | 3.7 | 0.71 | 1 | 39.1 | 3.5 | 0.59 | 1 | 43.5 | 3.5 | 0.67 | 1 | 60.9 | |

| Environmental visual compatibility | 95.7 | 3.1 | 0.42 | 0 | 82.6 | 3.2 | 0.39 | 0 | 82.6 | 3.1 | 0.46 | 0 | 91.3 | |

| Cession of port spaces | 95.7 | 3.7 | 0.79 | 1 | 56.5 | 3.6 | 0.58 | 1 | 52.2 | 3.6 | 0.59 | 1 | 47.8 | |

| Celebration of maritime activities | 100.0 | 3.7 | 0.56 | 1 | 60.9 | 3.4 | 0.90 | 1 | 30.4 | 3.4 | 0.78 | 1 | 52.2 | |

| Nautical promotion | 100.0 | 4.0 | 0.74 | 2 | 47.8 | 3.9 | 0.60 | 0 | 65.2 | 4.1 | 0.51 | 0 | 73.9 | |

| Diffusion and promotion of the surroundings | 95.7 | 3.7 | 0.83 | 1 | 56.5 | 3.8 | 0.60 | 1 | 60.9 | 3.6 | 0.89 | 1 | 43.5 | |

| Coordination with other agents * | 100.0 | 3.6 | 0.90 | 1 | 65.2 | 3.6 | 0.79 | 1 | 47.8 | |||||

| Transfer of sands and adjacent beach nourishment | 95.5 | 3.8 | 1.24 | 1.0 | 50.0 | 4.0 | 0.71 | 1 | 52.2 | 3.9 | 0.67 | 1 | 56.5 | |

| Focusing on intangible values * | 91.3 | 3.0 | 1.02 | 2 | 39.1 | 3.3 | 0.81 | 1 | 43.5 | |||||

| Surveillance | 100.0 | 4.2 | 0.67 | 0 | 56.5 | 4.1 | 0.46 | 0 | 78.3 | 4.0 | 0.52 | 0 | 73.9 | |

| Emergency plans | 100.0 | 4.2 | 0.72 | 1 | 47.8 | 4.1 | 0.85 | 1 | 65.2 | 3.9 | 0.92 | 1 | 52.2 | |

| Spatial separation of port uses | 100.0 | 3.9 | 0.73 | 1 | 47.8 | 3.7 | 0.78 | 1 | 30.4 | 3.4 | 0.84 | 1 | 56.5 | |

| Maintenance | Breakwaters | 100.0 | 4.5 | 0.70 | 1 | 43.5 | 4.4 | 0.50 | 1 | 60.9 | 4.2 | 0.67 | 1 | 52.2 |

| Seawalls | 100.0 | 4.5 | 0.69 | 1 | 47.8 | 4.3 | 0.56 | 1 | 60.9 | 4.1 | 0.67 | 1 | 56.5 | |

| Docks and berths | 100.0 | 4.5 | 0.59 | 1 | 43.5 | 4.6 | 0.51 | 1 | 56.5 | 4.5 | 0.67 | 1 | 34.8 | |

| Statutory services | 100.0 | 4.5 | 0.59 | 1 | 43.5 | 4.5 | 0.51 | 1 | 52.2 | 4.5 | 0.51 | 1 | 52.2 | |

| Pavements | 100.0 | 4.2 | 0.72 | 1 | 47.8 | 4.0 | 0.43 | 0 | 82.6 | 4.0 | 0.77 | 2 | 43.5 | |

| Buildings | 100.0 | 4.1 | 0.63 | 1 | 60.9 | 4.0 | 0.47 | 0 | 78.3 | 4.0 | 0.64 | 0 | 60.9 | |

| Public spaces and urban furniture | 100.0 | 4.0 | 0.67 | 0 | 56.5 | 3.9 | 0.51 | 0 | 73.9 | 3.9 | 0.60 | 0 | 65.2 | |

| Landscaping | 100.0 | 3.7 | 0.70 | 1 | 43.5 | 3.7 | 0.69 | 1 | 47.8 | 3.6 | 0.72 | 1 | 52.2 | |

* Criteria suggested during the survey process and included.

Table A2.

Statistical results from rounds related to the landscape of marinas (Delphi survey).

Table A2.

Statistical results from rounds related to the landscape of marinas (Delphi survey).

| Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity | Subject | P (x ≥ 3) | Md | SD | Q | % | Md | SD | Q | % | Md | SD | Q | % |

| Services | Occupancy of berths | 95.7 | 4.6 | 0.73 | 1 | 65.2 | 4.8 | 0.52 | 0 | 82.6 | 4.8 | 0.52 | 0 | 82.6 |

| Distribution of berths and piers | 100.0 | 4.2 | 0.60 | 1 | 60.9 | 3.6 | 0.59 | 1 | 60.9 | 4.5 | 0.51 | 1 | 52.2 | |

| Distribution of activities within the port area | 100.0 | 4.5 | 0.73 | 1 | 26.1 | 4.5 | 0.59 | 1 | 56.5 | 4.4 | 0.50 | 1 | 60.9 | |

| Boat handling and storage | 100.0 | 4.3 | 0.69 | 1 | 47.8 | 4.0 | 0.56 | 0 | 69.6 | 4.2 | 0.60 | 1 | 60.9 | |

| Shipyard and repair services | 100.0 | 4.1 | 0.73 | 1 | 47.8 | 4.0 | 0.71 | 1 | 52.2 | 4.1 | 0.69 | 1 | 52.2 | |

| Complementary uses | 100.0 | 3.9 | 0.90 | 2 | 21.7 | 3.7 | 0.63 | 1 | 52.2 | 3.7 | 1.06 | 1 | 50.0 | |

| Compatible uses | 95.7 | 3.8 | 0.98 | 2 | 39.1 | 3.7 | 0.70 | 1 | 43.5 | 3.7 | 0.88 | 1 | 52.2 | |

| Parking lots | 100.0 | 4.1 | 0.67 | 1 | 56.5 | 4.0 | 0.82 | 2 | 34.8 | 4.0 | 0.67 | 0 | 56.5 | |

| Landscaping | 95.7 | 3.3 | 0.69 | 0 | 73.9 | 3.3 | 0.56 | 1 | 73.9 | 3.2 | 0.65 | 1 | 69.6 | |

| Interferences of circulation flows | 100.0 | 4.0 | 0.74 | 2 | 47.8 | 3.9 | 0.63 | 1 | 60.9 | 3.7 | 0.63 | 1 | 52.2 | |

| Roadways | 100.0 | 3.7 | 0.62 | 1 | 56.5 | 3.9 | 0.69 | 1 | 52.2 | 3.7 | 0.63 | 1 | 52.2 | |

| Walkways and bike paths | 100.0 | 3.4 | 0.58 | 1 | 65.2 | 3.2 | 0.39 | 0 | 82.6 | 3.1 | 0.34 | 0 | 87.0 | |

| Port office | 95.7 | 3.8 | 0.95 | 1 | 43.5 | 3.8 | 0.67 | 1 | 52.2 | 3.4 | 0.99 | 1 | 39.1 | |

| Maritime signaling and beacons | 95.7 | 3.9 | 1.00 | 2 | 39.1 | 3.8 | 0.83 | 2 | 30.4 | 4.0 | 0.74 | 2 | 47.8 | |

| Services’ buildings | 95.7 | 3.9 | 0.95 | 2 | 47.8 | 3.8 | 0.65 | 1 | 56.5 | 3.9 | 0.63 | 1 | 60.9 | |

| Auxiliary elements | 100.0 | 3.4 | 0.59 | 1 | 60.9 | 3.4 | 0.90 | 1 | 56.5 | 3.3 | 0.45 | 1 | 73.9 | |

| Financial feasibility | Economic sustainability | 100.0 | 4.7 | 0.65 | 1 | 73.8 | 4.8 | 0.52 | 0 | 82.6 | 4.8 | 0.52 | 0 | 82.6 |

| Environmental | Water quality | 95.7 | 4.0 | 1.04 | 2 | 30.4 | 4.0 | 0.80 | 2 | 39.1 | 3.7 | 0.71 | 1 | 39.1 |

| management | Environmental quality | 100.0 | 4.3 | 0.81 | 2 | 34.8 | 4.1 | 0.69 | 1 | 52.2 | 4.0 | 0.64 | 0 | 60.9 |

| Waste management | 100.0 | 4.0 | 0.85 | 2 | 30.4 | 4.2 | 0.58 | 1 | 65.2 | 4.1 | 0.55 | 0 | 69.6 | |

| Contingency plans against marine pollution | 100.0 | 4.1 | 0.76 | 1 | 43.5 | 4.1 | 0.76 | 1 | 43.5 | 4.0 | 1.04 | 2 | 30.4 | |

| Environmental management certificate | 95.7 | 3.7 | 0.90 | 1 | 39.1 | 3.7 | 0.63 | 1 | 52.2 | 3.9 | 0.81 | 0 | 69.6 | |

| Accessibility and permeability | 100.0 | 3.6 | 0.58 | 1 | 52.2 | 3.9 | 0.73 | 1 | 47.8 | 3.8 | 0.72 | 1 | 47.8 | |

| Adjoining uses | 100.0 | 3.7 | 0.71 | 1 | 39.1 | 3.5 | 0.59 | 1 | 43.5 | 3.5 | 0.67 | 1 | 60.9 | |

| Environmental visual compatibility | 95.7 | 3.1 | 0.42 | 0 | 82.6 | 3.2 | 0.39 | 0 | 82.6 | 3.1 | 0.46 | 0 | 91.3 | |

| Cession of port spaces | 95.7 | 3.7 | 0.79 | 1 | 56.5 | 3.6 | 0.58 | 1 | 52.2 | 3.6 | 0.59 | 1 | 47.8 | |

| Celebration of maritime activities | 100.0 | 3.7 | 0.56 | 1 | 60.9 | 3.4 | 0.90 | 1 | 30.4 | 3.4 | 0.78 | 1 | 52.2 | |

| Nautical promotion | 100.0 | 4.0 | 0.74 | 2 | 47.8 | 3.9 | 0.60 | 0 | 65.2 | 4.1 | 0.51 | 0 | 73.9 | |

| Diffusion and promotion of the surroundings | 95.7 | 3.7 | 0.83 | 1 | 56.5 | 3.8 | 0.60 | 1 | 60.9 | 3.6 | 0.89 | 1 | 43.5 | |

| Coordination with other agents * | 100.0 | 3.6 | 0.90 | 1 | 65.2 | 3.6 | 0.79 | 1 | 47.8 | |||||

| Transfer of sands and adjacent beach nourishment | 95.5 | 3.8 | 1.24 | 1.0 | 50.0 | 4.0 | 0.71 | 1 | 52.2 | 3.9 | 0.67 | 1 | 56.5 | |

| Focusing on intangible values * | 91.3 | 3.0 | 1.02 | 2 | 39.1 | 3.3 | 0.81 | 1 | 43.5 | |||||

| Surveillance | 100.0 | 4.2 | 0.67 | 0 | 56.5 | 4.1 | 0.46 | 0 | 78.3 | 4.0 | 0.52 | 0 | 73.9 | |

| Emergency plans | 100.0 | 4.2 | 0.72 | 1 | 47.8 | 4.1 | 0.85 | 1 | 65.2 | 3.9 | 0.92 | 1 | 52.2 | |

| Spatial separation of port uses | 100.0 | 3.9 | 0.73 | 1 | 47.8 | 3.7 | 0.78 | 1 | 30.4 | 3.4 | 0.84 | 1 | 56.5 | |

| Maintenance | Breakwaters | 100.0 | 4.5 | 0.70 | 1 | 43.5 | 4.4 | 0.50 | 1 | 60.9 | 4.2 | 0.67 | 1 | 52.2 |

| Seawalls | 100.0 | 4.5 | 0.69 | 1 | 47.8 | 4.3 | 0.56 | 1 | 60.9 | 4.1 | 0.67 | 1 | 56.5 | |

| Docks and berths | 100.0 | 4.5 | 0.59 | 1 | 43.5 | 4.6 | 0.51 | 1 | 56.5 | 4.5 | 0.67 | 1 | 34.8 | |

| Statutory services | 100.0 | 4.5 | 0.59 | 1 | 43.5 | 4.5 | 0.51 | 1 | 52.2 | 4.5 | 0.51 | 1 | 52.2 | |

| Pavements | 100.0 | 4.2 | 0.72 | 1 | 47.8 | 4.0 | 0.43 | 0 | 82.6 | 4.0 | 0.77 | 2 | 43.5 | |

| Buildings | 100.0 | 4.1 | 0.63 | 1 | 60.9 | 4.0 | 0.47 | 0 | 78.3 | 4.0 | 0.64 | 0 | 60.9 | |

| Public spaces and urban furniture | 100.0 | 4.0 | 0.67 | 0 | 56.5 | 3.9 | 0.51 | 0 | 73.9 | 3.9 | 0.60 | 0 | 65.2 | |

| Landscaping | 100.0 | 3.7 | 0.70 | 1 | 43.5 | 3.7 | 0.69 | 1 | 47.8 | 3.6 | 0.72 | 1 | 52.2 | |

* Criteria suggested during the survey process and included.

Appendix B

This appendix contains the final results for the two-round Delphi and AHP survey related to management activities.

Table A3.

Statistical results related to management of marinas (DHP survey).

Table A3.

Statistical results related to management of marinas (DHP survey).

| Round 1 | Round 2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activity | P (x ≥ 3) | Md | SD | Q | % | Md | SD | Q | % |

| Services | 100.0 | 6.6 | 0.87 | 1.0 | 73.7 | 6.9 | 0.33 | 0.0 | 82.2 |

| Financial feasibility | 94.7 | 6.2 | 1.13 | 1,0 | 31.6 | 6.5 | 0.62 | 1.0 | 52.9 |

| Environmental management | 94.7 | 5.6 | 1.11 | 2.0 | 36.8 | 5.8 | 1.15 | 0.0 | 58.8 |

| Maintenance | 94.7 | 6.1 | 1.07 | 1.0 | 42.1 | 6.2 | 0.66 | 1.0 | 52.9 |

In the AHP method, the eigenvalues are obtained from the comparison matrix of each element. The maximum value (λmax) is used to calculate the consistency index (CI) through the following expression, where n is the size of the matrix:

CI = (λmax − n)/(n − 1)

This index is compared with the random consistency. Its value is related to n. This quotient is called the consistency ratio (CR). Consistency is considered to exist when the percentage does not exceed 9% for n = 4.

CR = CI/random consistency

The results obtained for the consistency matrices are shown in Table A4.

Table A4.

Weighted coefficient related to marinas’ management activities.

Table A4.

Weighted coefficient related to marinas’ management activities.

| Services Provided | Financial Feasibility | Environmental Management | Maintenance | CR (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent 1 | 0.2994 | 0.2389 | 0.2530 | 0.2087 | 7.0 |

| Rank | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | |

| Respondent 2 | 0.1951 | 0.5499 | 0.0771 | 0.1769 | 0.6 |

| Rank | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | |

| Respondent 3 | 0.3952 | 0.2781 | 0.1634 | 0.1634 | 2.3 |

| Rank | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | |

| Respondent 4 | 0.3399 | 0-4124 | 0.0511 | 0.1967 | 4.7 |

| Rank | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | |

| Respondent 5 | 0.4111 | 0.2180 | 0.0865 | 0.2844 | 4.6 |

| Rank | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | |

| Average | 0.3283 | 0.3394 | 0.1262 | 0.2060 | |

| Rank | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 |

Appendix C

To apply discriminant analysis, we started from the evaluation results of the elements, both from a management and landscape perspective. We obtained the difference between both values. This difference represented the categorical variable. The results were grouped into three continuous variables, depending on the difference value (ABS 0.0015): (1) Management (more management influence); (2) Landscape (more landscape influence); and (3) Equal (similar management and landscape influence).

Table A5.

Grouping of the elements in the variables (1—Management, 2—Equal, 3—Landscape).

Table A5.

Grouping of the elements in the variables (1—Management, 2—Equal, 3—Landscape).

| Num. | Element | Gross Values | Weighted Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Occupancy of berths | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | Distribution of berths and piers | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | Distribution of activities within the port area | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | Boat handling and storage | 3 | 1 |

| 5 | Shipyard and repair services | 3 | 3 |

| 6 | Complementary uses | 3 | 3 |

| 7 | Compatible uses | 3 | 3 |

| 8 | Parking lots | 3 | 3 |

| 9 | Landscaping | 2 | 2 |

| 10 | Interferences of circulation flows | 3 | 3 |

| 11 | Roadways | 3 | 3 |

| 12 | Walkways and bike paths | 2 | 2 |

| 13 | Port office | 2 | 2 |

| 14 | Maritime signaling and beacons | 3 | 3 |

| 15 | Services’ buildings | 3 | 3 |

| 16 | Auxiliary elements | 3 | 2 |

| 17 | Economic sustainability | 1 | 1 |

| 18 | Water quality | 2 | 2 |

| 19 | Environmental quality | 2 | 2 |

| 20 | Waste management | 3 | 3 |

| 21 | Contingency plans against marine pollution | 1 | 1 |

| 22 | Environmental management certificate | 1 | 1 |

| 23 | Accessibility and permeability | 3 | 3 |

| 24 | Adjoining uses | 2 | 2 |

| 25 | Environmental visual compatibility | 2 | 2 |

| 26 | Cession of port spaces | 3 | 3 |

| 27 | Celebration of maritime activities | 3 | 3 |

| 28 | Nautical promotion | 1 | 1 |

| 29 | Diffusion and promotion of the surroundings | 2 | 2 |

| 30 | Coordination with other agents | 1 | 3 |

| 31 | Transfer of sands and adjacent beach nourishment | 2 | 2 |

| 32 | Focusing on intangible values | 3 | 3 |

| 33 | Surveillance | 2 | 2 |

| 34 | Emergency plans | 1 | 1 |

| 35 | Spatial separation of port uses | 2 | 2 |

| 36 | Breakwaters | 1 | 1 |

| 37 | Seawalls | 1 | 1 |

| 38 | Docks and berths | 1 | 1 |

| 39 | Statutory services | 1 | 1 |

| 40 | Pavements | 3 | 3 |

| 41 | Buildings | 3 | 3 |

| 42 | Public spaces and urban furniture | 3 | 2 |

| 43 | Landscaping | 2 | 2 |

The aim was to assess how well the continuous variables separate the category in the classification. For this, we used the SPSS program, which performs canonical linear discriminant analysis. The magnitudes of the eigenvalues are indicative of the functions’ discriminating abilities. The higher the eigenvalue value, the more effective the analysis in classifying items into variables. The canonical correlation captures the membership of the elements in the variable. The closer it is to unity, the better the fit.

In both cases, after the first values obtained and the analysis of the eigenvalue and the canonical correlation, we conclude that there is a discriminant function that allows us to significantly classify the elements in the variables.

Table A6.

Summary of the canonic discriminant functions.

Table A6.

Summary of the canonic discriminant functions.

| Eigenvalues | ||||

| Function | Eigenvalue | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Canonical Correlation |

| Gross values | 1.392 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.763 |

| Weighted values | 0.395 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 0.532 |

| Wilks’ Lambda | ||||

| Test function | Wilks’ Lambda | Chi-square | gl | Sig. |

| Gross values | 0.418 | 34.891 | 2 | 0.000 |

| Weighted values | 0.717 | 13.314 | 2 | 0.001 |

References

- Marrou, L. Nautical frequentation and marina management. J. Coast. Res. 2011, 61, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüzbaşioğ, N.; Dogan, O. Strategic governance in the marina sector in the context of marine tourism cluster. Almatourism J. Tour. Cult. Territ. Develop. 2021, 12, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benevolo, C.; Spinelli, R. Benefit segmentation of pleasure boaters in Mediterranean marinas: A proposal. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 23, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundula, L.; Ladu, M.; Balletto, G.; Milesi, A. Smart Marinas. The case of metropolitan city of Cagliari. In Proceedings of the Computational Science and its Applications—ICCSA, 20th International Conference, Cagliari, Italy, 1–4 July 2020; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Garau, C., Blečić, I., Taniar, D., Apduhan, B.O., Rocha, A.M., Tarantino, E., Torre, C.M., Karaca, Y., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; pp. 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Pérez, N.; Dessimoz, M.D.; Rodríguez-Martín, J.; Gartía, C.; Ioras, F.; Santamata, J.C. Carbon and water footprints of marinas in the Canary Islands (Spain). Coast. Manag. 2022, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Vázquez, R.M.; de Pablo Valenciano, J.; Milán-García, J. Impact analysis of marinas on nautical tourism in Andalucia. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 7, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebot, N.; Rosa-Jiménez, C.; Pié Ninot, R.; Perea-Medina, B. Challenges for the future of ports. What can be learnt from the Spanish Mediterranean ports? Ocean Coast. Manag. 2017, 137, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizarri, C.; La Foresta, D. Yachting and pleasure crafts in relation to local development and expansion: Marina di Stabia case study. In WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment: Coastal Processes II; Benassai, G., Brebbia, C.A., Rodríguez, G., Eds.; WITT Press: Southampton, UK, 2011; Volume 149, pp. 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martín, R.; Yepes, V.; Grindlay, A. Discovering the marina’s cultural heritage and cultural landscape. In Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium Monitoring of Mediterranean Coastal Areas, Problems and Measurement Techniques, Livorno, Italy, 16–18 June 2020; Bonora, L., Carboni, E., De Vincenzi, M., Eds.; Firenze University Press: Firenze, Italy, 2020; pp. 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, R.; Yepes, V. El paisaje en la planificación y gestión de los puertos deportivos en Andalucía [The landscpe in the planning and management of marinas in Andalucia]. Rev. Obras Públicas 2017, 164, 38–55. [Google Scholar]

- Paker, N.; Vural, C.A. Customer segmentation for marinas: Evaluating marinas as destinations. Tour. Manag. 2016, 56, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, E.D.; Ziros, L.A. Yachts and marinas as hotspots of coastal risk. Anthr. Coasts 2021, 4, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raviv, A.; Tarba, S.Y.; Weber, Y. Strategic planning for increasing profitability: The case of marina industry. EuroMed J. Bus. 2009, 4, 200–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanwick, C. Landscape Character Assessment. Guidance for England and Scotland, The Countryside Agency-Scottish Natural Heritage. 2002. Available online: https://www.nature.scot/landscape-character-assessment-guidance-england-and-scotland (accessed on 14 October 2021).

- Council of Europe. European Landscape Convention and Explanatory Report; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2000; Available online: https://rm.coe.int/CoERMPublicCommonSearchServices/DisplayDCTMContent?documentId=0900001680080621 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- McKinley, E.; Harvey, R.; Ballinger, R.C.; Davidson, K.; Griffin, J.N.; Skov, M.W. Coastal agricultural landscapes: Mapping and understanding grazing intensity on Welsh saltmarshes. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2022, 222, 106128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Matsuda, H.; Fukushi, K.; Takeuchi, K.; Watanabe, R. The missing intangibles: Nature’s contributions to human well-being through place attachment and social capital. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 17, 809–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, I.R. Towards sustainable urbanization of coastal cities: The case of Al-Arish City, Egypt. Ain. Shams. Eng. J. 2021, 12, 2285–2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, R.; Yepes, V. The concept of landscape within marinas: Basis for consideration in the management. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 179, 104815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yepes, V.; Medina, J.R. Land use tourism model in Spanish coastal areas. A case study of the Valencia Region. J. Coast. Res. 2005, 49, 83–88. [Google Scholar]

- Petrosillo, I.; Valente, D.; Zaccarelli, N.; Zurlini, G. Managing tourist harbors: Are managers aware of the real environmental risks? Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2009, 58, 1454–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete-Hernandez, P.; Vetro, A.; Concha, P. Building safer public spaces: Exploring gender difference in the perception of safety in public spaces through urban design interventions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 214, 104180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benevolo, C.; Spinelli, R. The use of websites by Mediterranean tourist ports. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2019, 10, 190–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Giu, h.; Morrison, A.M.; Wei, W.; Zhang, X. Landscape and unique fascination: A dual-case study on the antecedents of tourist pro-environmental behavioral intentions. Land 2022, 11, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicer, E.; Yepes, V.; Correa, C.L.; Alarcón, L.F. Model for systematic innovation in construction companies. J. Const. Eng. Manag. 2014, 140, 84014001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, T.; Keane, T.; Kaplan, S. Aesthetics and management: Bridging the gap. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1986, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roff, S. Landscape Design Guidelines for Marinas. Ph.D. Thesis, Lincoln College, University of Canterbury, Lincoln, New Zealand, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Chaney, C.A. Marinas. Recommendations for Design, Construction and Maintenance, 2nd ed.; National Association of Engine and Boat Manufacturers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Obras Públicas. La Cuarta Flota. Directrices Aplicables a la Promoción de Pniciativas. In The Fourth Fleet. Guidelines Applicable to the Promotion of Initiatives; Servicio de Publicaciones MOP: Madrid, Spain, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Adie, D.W. Marinas. A Working Guide to their Development and Design, 3rd ed.; The Architectural Press Ltd.: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Mann, R.B. Ten trends in the continuing renaissance of urban waterfronts. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1988, 16, 177–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, P. Porti turistici: Una disciplina e una sfida [Marinas: A discipline and a challenge]. Portus 2005, 9, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Blain, W.R. (Ed.) Marina Technology. Proceedings of the Second International Conference; Computational Mechanics Publications: Southampton, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Girard, L.F. Towards a smart sustainable development of port/cities areas: The role of the “Historic Urban Landscape” approach. Sustainability 2013, 5, 4329–4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trisutomo, S. Visual assessment on coastal cruise tourism: A preliminary planning using importance-performance analysis. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2017, 79, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piwowarczyk, J.; Kronenberg, J.; Dereniowska, M.A. Marine ecosystem services in urban areas: Do the strategic documents of Polish coastal municipalities reflect their importance? Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 109, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, M. Coastal and marine tourism: A challenging factor in Marine Spatial Planning. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 129, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogg, O.T.; Huvenne, V.A.I.; Griffiths, H.J.; Linse, K. On the ecological relevance of landscape mapping and its application in the spatial planning of very large marine protected areas. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 626, 334–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinley, E. Marinas 2020: A Vision for the Future Sustainability of Channel/Arc Manche Marinas. Industry Report. Recommendations for Best Practice. 2020. Available online: http://eprints.chi.ac.uk/id/eprint/1743/1/Marina%202020%20industry%20report%20FINAL.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2021).

- Mooser, A.; Anfuso, G.; Mestanza, C.; Williams, A.T. Management implications for the most attractive scenic sites along the Andalusia coast (SW Spain). Sustainability 2018, 10, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Robert, S. Assessing the visual landscape potential of coastal territories for spatial planning. A case study in the French Mediterranean. Land Use Policy 2018, 72, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, R.; Yepes, V. Bridging the gap between landscape and management within marinas: A review. Land 2021, 10, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, H.; Peters, M.; Foster, C.; Black, N.; Fitzpatrick, R. A core outcome set for randomized controlled trials of physical activity interventions: Development and challenges. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassanain, M.A.; Sanni-Anibire, M.O.; Mahmoud, A.S. Development of a design quality indicators toolkit for campus facilities using the Delphi approach. J. Archit. Eng. 2022, 28, 04022006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehrle, M.; Birkel, H.; von der Gracht, H.A.; Hartmann, E. The impact of digitalization on the future of the PSM function managing purchasing and innovation in new product development—Evidence from a Delphi study. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2022, 28, 100732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linstone, H.A.; Turoff, M. (Eds.) The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications; Addison-Wesley Publishing Company: Reading, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Luup, G.; Konold, W.; Bastian, O. Landscape management and landscape changes towards more naturalness and wilderness: Effects on scenic qualities—The case of the Müritz National Park in Germany. J. Nat. Conserv. 2013, 21, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flinzberger, L.; Zinngrebe, Y.; Plieninger, T. Labelling in Mediterranean agroforestry landscapes: A Delphi survey on relevant sustainability indicators. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 1369–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Urbis, A.; Povilanskas, R.; Šimanauskiene, R.; Taminskas, J. Key aesthetic appeal concepts of coastal dunes and forests on the example for the Curonian Spit (Lithuania). Water 2019, 11, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saati, T. The Analytical Hierarchy Process; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, S.; Ding, H.; Zeng, Y. Evaluating water-yield property of karst aquifer based on the AHP and CV. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Zhao, F. A quantitative evaluation based on an analytic hierarchy process for the deterioration degree of the Guangyuan Thousand-Buddha grotto from the Tang Dynasty in Sichuan, China. Herit. Sci. 2022, 10, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, W.M. Supporting a decision for metro station restoration based on facility assessment: Application to Cairo metro stations. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2022, 69, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenso-Díaz, B.; García-Álvarez, N.; Lago-Alba, J.A. A fuzzy AHP classification of container terminals. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2020, 22, 218–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, R.D.; Becker, A. Applying MCDA to weight indicators of seaport vulnerability to climate and extreme weather impacts for U.S. North Atlantic ports. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2020, 40, 256–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gumusay, M.U.; Koseoglu, G.; Bakirman, T. An assessment of site suitability for marina construction in Istanbul, Turkey, using GIS and AHP multicriteria decision analysis. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2016, 188, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, G.; Wright, G. The Delphi technique: Past, present, and future prospects. Introduction to the special issue. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2011, 78, 1487–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorramshahgol, R.; Moustakis, V.S. Delphic hierarchy process (DHP): A methodology for priority setting derived from the Delphi method and analytical hierarchy process. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1988, 37, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallowell, M.R.; Gambatese, J.A. Qualitative research: Application of the Delphi method to CEM research. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2010, 136, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roßmann, B.; Canzaniello, A.; von der Gracht, H.; Hartmann, E. The future and social impact of Big Data Analytics in supply chain management: Results from a Delphi study. Technol. Forecast. Social Chang 2018, 130, 135–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, C.; Carmona, M. Dimensions and models of contemporary public space management in England. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2009, 52, 111–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murry, J.W.; Hammons, J.O. Delphi: A versatile methodology for conducting qualitative research. Rev. High. Ed. 1995, 18, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holey, E.A.; Feeley, J.L.; Dixon, J.; Whittaker, V.J. An exploration of the use of simple statistics to measure consensus and stability in Delphi studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2007, 7, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hsu, C.C.; Sandford, B.A. The Delphi technique: Making sense of consensus. Pract. Assess. Rese. Eval. 2007, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Aznar, J.; Guijarro, F. Nuevos Métodos de Valoración. Modelos Multicriterio [New Valuation Methods. Multicriteria Models]; Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València: Valencia, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hacia, E.; Lapko, A. Staff training for the purposes of marina management. Res. Pap. Wroc. Univ. Econ. Bus. 2019, 63, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maglić, L.; Grbčić, A.; Maglić, L.; Gundić, A. Application of smart technologies to Croatian marinas. Trans. Marit. Sci. 2021, 10, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazançoğlu, İ.; Karaosmanoğlu, C. Can sustainability marketing be implemented as a differentiation strategy? In Supply Chain Sustainability: Modeling and Innovative Research Frameworks; Mangla, S.K., Ram, M., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Vázquez, R.M.; de Pablo Valenciano, J.; Caparrós-Martínez, J.L. Marinas and sustainability: Directions for future research. J. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 164, 112035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECSIP (European Competitiveness and Sustainable Industrial Consortium). Study of the Competitiveness of the Recreational Boating Sector. Final Report. 2015. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/vto/content/study-competitiveness-recreational-boating-sector (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Rodiek, J. The evolving landscape. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1988, 16, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, G. The Concise Townscape; Architectural Press: Oxford, UK, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. Site Planning, 2nd ed.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Pinder, D. Seaport decline and cultural heritage sustainability issues in the UK coastal zone. J. Cult. Herit. 2003, 4, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loupa Ramos, I.; Bernardo, F.; Carvalho Ribeiro, S.; Van Eetvelde, V. Landscape identity: Implications for policymaking. Land Use Policy 2016, 53, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Egoz, S. Landscape and identity: Beyond a geography of one place. In The Routledge Companion to Landscape Studies; Thompson, I., Howard, P., Waterton, E., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 272–285. [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth, G.; Page, S.J. Urban tourism research: Recent progress and current paradoxes. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemany, J.; Bruttomesso, R. (Eds.) The Port City. New Challenges in the Relationship between Port and City; Rete: Venice, Italy, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Grindlay, A.L.; Martínez-Hornos, S. City-port relationships in Málaga, Spain: Effects of the new port proposals on urban traffic. In WIT Transactions on the Built Environment: Urban Transport XXIII; Ricci, S., Brebbia, C.A., Eds.; WITT Press: Southampton, UK, 2017; Volume 176, pp. 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cao, Y.; Tang, X. Evaluation the effectiveness of community public open space renewal: A case study of the Ruijin Community, Shanghai. Land 2022, 11, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frampton, K.T. Towards a critical regionalism: Six points for an architecture of resistance. In The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture; Hoster, H., Ed.; The New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983; pp. 16–32. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Genius Loci. Paesaggio, Ambiente, Architettura [Genius Loci. Landscape, Environment, Architecture]; Electra: Milano, Italy, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiló, M. El Paisaje Construido. Una Aproximación a la Idea de Lugar [The Landscape Built. An Approximation to the Idea of Place]; Colegio de Ingenieros de Caminos, Canales y Puertos: Madrid, Spain, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, C.J.; Kahn, A. (Eds.) Site Matters: Design Concepts, Histories and Strategies; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gatersleben, B.; Wyles, K.J.; Myers, A.; Opitz, B. Why are places so special? Uncovering how our brain reacts to meaningful places. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 197, 103758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, G.; Wright, G. The Delphi technique as a forecasting tool: Issues and analysis. Int. J. Forecast. 1999, 15, 353–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. Recommendation CM/Rec(2008)3 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States on the Guidelines of the Implementation of the European Landscape Convention. 2008. Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16802f80c9 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).