We divide our discussion into three sections. First, we reveal what our case study highlighted for those seeking to increase the adoption of RegenAg practices in Australia. Second, we explain what the experience of using FCM to study this issue means for the communication of complexity within PM practice, and we outline some of the advantages and limitations of remote facilitation methods and strategies that could be applied during and beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. Third, we discuss what can be learned and applied for future PM exercises seeking to improve the management of SES before concluding this section with the limitations of our study and what that means for future research opportunities.

5.1. Solutions for Regenerative Agriculture

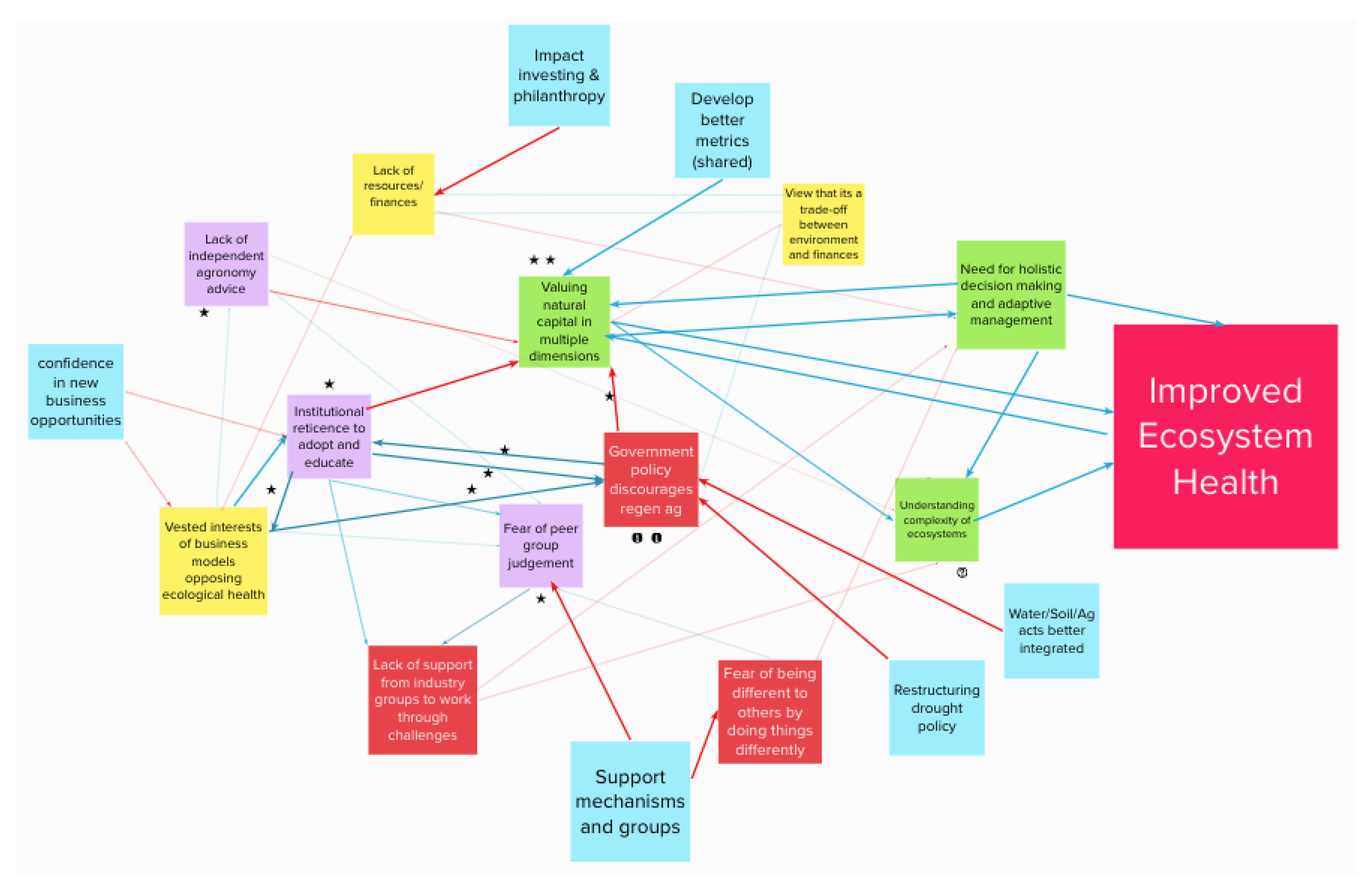

This case study and the results of the workshop highlight that the actions needed to increase the adoption of RegenAg must break the current ’reinforcing’ paradigm of conventional agriculture. Stakeholders, a mix of landholders, trainers, researchers, and advocates, drew on their experience and knowledge to identify relationships within the Australian agricultural paradigm. Currently, business, government, the market, and social pressures seem to spiral down together in a race to the bottom, with few existing relationships in the system to incentivise a transformation. Understanding these complex forces highlights the need for coordinated actions at the institutional, social, and individual levels, across immediate and long timescales (decades). It is vital that RegenAg advocates find the messages and actions that overcome any paralysis of action in individuals and in communities [

82].

One notable point in the FCM is the lack of balancing arrows (red arrows) within the system without the presence of the ‘levers’—the blue icons noting actions we can take. Many of these were discussed or identified during the Modelling stage of the workshop as possible ‘solutions’. If the ‘levers’ or actions we can take to act in the system are removed, the number of balancing connections in our model reduces by nearly half, going from 48 to 27 negative relationships, meaning the ability of the system to deliver on the outcome of interest ‘Improved Ecosystem Health’ becomes diminished. If there is a push for conventional agriculture, the system, as it is currently drawn, intensifies that push. This impetus can rapidly move in a ‘race to the bottom’, enshrining the dominant paradigm of conventional agriculture in a downward spiral as degrading land leads to more artificial inputs, leading to further degrading land and more money and incentives being put into the system to prop it up.

The supportive, even reinforcing nature of the agricultural paradigm and the relationships between entities (government, business, and consumers) has the potential to ‘lock-in’ these conventional agricultural practices, as it is difficult for RegenAg to break into those relationships. Without significant policies or actions to provide a balancing relationship, there is no obvious incentive to change. Climate change could be one incentive, as it presents a severe challenge to human society. However, its impacts are often unclear, disputed, or occur over the long term. Without making the severe consequences of conventional agriculture (through impacts on climate change, biodiversity, human health, or something else) immediately apparent, it is difficult for RegenAg to generate enough urgency to push through.

While it is important to note this may not necessarily reflect the reality of the system (those balancing feedbacks may or may not exist regardless of what is shown here), the fact that stakeholders in favor of RegenAg believe this to be true is striking. This insight leads to the question: how can those balancing relationships be introduced to the system? This question is of interest to financial institutions and governments, many of whom have already begun work in this area. To increase the adoption of RegenAg, institutions can begin to investigate these balancing feedbacks, including but not limited to examining how ’support from industry groups’ can depress fear of judgment or how the ’vested interests of business’ might be aligned with instead of against valuing natural capital. As an example of a balancing relationship, for example, determining where and how to value natural capital would be vital for those seeking to increase the adoption of RegenAg. Such efforts may also address the difficulties of “going green when you’re in the red.” These and other opportunities present a possibility for more balancing relationships within the system. The levers on the FCM also represent possible policy/intervention opportunities that workshop participants perceive as fundamentally relevant to a wider adoption of RegenAg in Australia. These opportunities are further discussed and explored in the five narratives. Notably, the solutions outlined under the five narratives coincide in the need for well coordinated, multi-scale (state; catchment, community) and multi-actor (federal, state, local government; industry; farmers and local communities) efforts to promote the desired shift from traditional to RegenAg practices. This need for work at various scales is documented within the research and the RegenAg movement (Chapman, 2019; Gordon, 2020; Murphy, 2021). As noted by [

21], there are a number of ‘spheres’ or scales in which to push for RegenAg, including the personal, the practical, and the political. Our work found a similar pattern. What is clear from our exercise is that among RegenAg practitioners, the role institutions play seems to matter to them a great deal, but they also note the interactions with social groups and personal identities and habits.

In addition, a number of barriers identified during the workshop, including an upfront cost to convert to regenerative, debt levels, lack of resources, and an ingrained view that environmental and economic outcomes cannot both be achieved, all suggest that a transition to RegenAg is expensive. This expense may or may not reflect reality, particularly when considering the return on investment and resilience offered by many RegenAg practices, but the ‘perception’ of the expense seems to be important for those considering a transition.

The FCM process also noted behavioral traps and pain points of individual farmers, which are perhaps just as difficult, if not more so, to change than government policy. This includes ‘

Fear of change’, ’

Fear of Being Different...,’ and ‘

Fear of judgment from peers’. As an area perhaps less explored within agricultural policy, but with a growing body of research on the importance of stakeholder outreach and ’tailored’ communication [

83,

84], there is a potential to change ‘faster’ through education and outreach. We, like others [

21], advocate that education and outreach should centre on the personal sphere, aiming for critical awareness [

85], reflection [

86,

87] and transformative learning [

88,

89] that allows for the deeper questioning and altering of underlying values and beliefs [

68].

Based on the FCM that was elicited, the narratives derived from it, and follow-up discussions with workshop participants, we identify several recommended areas of focus to improve the adoption of RegenAg in Australia at various scales:

Narrative 1: Government First—If ‘Big Government’ is the problem, then ‘Big Government’ must be a part of the solution. This includes a coordinated effort from federal and state governments. While noting the effect the individual voters and media have on the government, if this narrative is true, a drastic reform of government policy is needed. More incentives need to be provided for a switch to RegenAg, and they could show up in a reform of drought policy or an integration of water and soil acts, which are perhaps more in line with watershed boundaries as opposed to arbitrary geopolitical ones. Stakeholders noted that not only does this commitment need to be significant, it also needs to be ‘long-term’ in order to align with the cycles of natural capital and to “give confidence to land managers, industry, educational institutions, NGOs, and the broader public.” Part of that effort could then include greater efforts to inform the voting public of RegenAg interests and actively push Parliament to embrace policies benefiting RegenAg by direct lobbying from RegenAg advocates and practitioners towards the relevant departments and ministers.

Narrative 2: The Market Matters—Find ways to increase consumer demand for products of RegenAg (affecting ‘Consumer Demand for Cheap Food’ and ‘Market Demand’ for “Clean and Green’’), which could happen in a number of ways:

Provide government incentives to subsidise the cost of regenerative products, either in out-of-the-gate packaging and production, or in reducing the high upfront costs needed to switch to regenerative.

Create regional processing and distribution centres in high agricultural areas devoted to regenerative products and lowering costs by producing at scale.

Incentivise supermarkets to carry regenerative products either at lower prices or in high-value locations in stores to encourage more sales.

Increase funding to marketing and advertising to craft a more compelling narrative for regenerative products to direct-sell to consumers

Narrative 3: Pressured Communities—‘Normalise uptake’ of RegenAg practices to remove any social stigma that comes from such a transition or practice. Being able to point to socially accepted indicators of success, or cultural capital [

18,

80,

81] for regenerative farmers, such as increased income or production, can help shield such farmers from criticism. Therefore, building up evidence and case studies to complement these transitions, ideally over the long term, can help. In addition, identifying and working with local and community champions, which could include members of local councils, NGOs, or fellow farmers, could present additional social visibility and support. Providing training and support and building “communities of practitioners and networks of conversation” can also assist and can span across regions due to the access and ease of the internet and social media channels.

Narrative 4: Start with People—Appropriate solutions would need to address the fear that underlies much of the social and institutional resistance. ’Inducing epiphanies’ as sought by [

21] would be crucial. Education and outreach to converse and and engage in dialogue with skeptics would be central to this effort, with the ultimate aims of transforming the hearts and minds of the agricultural industry, highlighting the “hope, dreams, and aspirations” of “leaving the land in better shape for the next generation”. This would also include better marketing and targeting of consumers to have them switch to products of RegenAg. However, the timescale for this scale of change, as noted by participants, is likely to take decades.

Narrative 5: Community by Community—In recognition of different geographical areas and bio-regions requiring different land use and management approaches, this narrative recognises that solutions should be implemented both at the catchment and community scale. By having a community or catchment working together, an organisation (non-profit or even a government department) can identify solutions that mutually benefit the organisation at multiple levels, including but not limited to increased production, better profit margins, stronger social ties, or greater environmental benefits. This could involve coordinating with local councils and farmers within the catchment and would necessitate an organising body (such as TMI) to ensure that the appropriate training, education, and support were being delivered for the community needs. By converting a whole community, one can benefit from the economies of scale that can be delivered as well as the combined expertise.

The bottom line is that it is critical to engage stakeholders in the adoption of RegenAg, as it is both a context-specific area of practice within the limits of the land and, crucially, the adoption of RegenAg is a personal and social issue [

23,

90,

91]. We believe therefore that building on the current study, perhaps by further investigating the validity of the narratives and their implications, could identify further actions to take to improve adoption as well as highlight additional barriers that the movement may face and that were not apparent to the participants of our FCM workshop. Blindspots in the FCM could be illuminated by input from and conversations with the voices and perceptions from conventional agriculture. By understanding the focus of different (and at times opposing) stakeholder groups, PM practitioners could focus future workshop discussions on those actions and policies upon which there is both broad consensus and a sufficient evidence base to operate. FCM was a suitable tool for us to use to negotiate this effort in a small sample size, and it may be worth exploring in subsequent PM exercises with other stakeholders of Australian agriculture, including conventional farmers.

A note of caution is due here, since this was one case study with a limited number of participants, and the participants were largely in favour of RegenAg. It is important to bear in mind the possible bias in these responses. With a small sample size, the findings might not be representative of the system at large, and these results therefore need to be interpreted with caution. However, the PM exercise that is reported here points to narratives of interest and identifies several variables and relationships worthy of further investigation. Each of these narratives could be improved and/or challenged by asking questions such as “How do we know this to be true?”, “What would need to be seen for it to be proven true/false?”, “What might some indications be to show that we are wrong?” However, these critical questions cannot be asked if there is nothing to explore in the first place.

Another source of uncertainty is the inherent complexity of the socio-ecological system we are studying here. A farm is subject to consumer demand, market prices, government policy, social pressures from peers and family, environmental disasters, long-term climatic trends, access to education and research, and the struggle to get up early in the morning. It is impossible to know with absolute certainty the status of some of these variables or the nature of their relationships. In this sense, the model here does not, and cannot, perfectly reflect reality (the map is not the territory, [

92]). Not only that, but some of these barriers, particularly institutional ones, are not only complex but slow moving, requiring huge efforts and investments to drive change over the long term. Left untouched, this seemingly insurmountable challenge could be discouraging. Complexity and uncertainty, however, cannot be an excuse for inaction. The identification of key variables and relationships, as we have done here, provides one path forward to asking better questions and finding more targeted actions. The PM exercise and the FCM produced provides a blueprint of the first steps we should be taking to untangle the complexity and uncertainty of the system in attunement with people’s beliefs and perceptions of how the agricultural paradigm operates. With these new insights in hand, our knowledge of the system becomes a little more complete, and we can work with stakeholders to look for new leverage points for change.

5.2. Reporting FCM

Our FCM analysis was useful for understanding the various barriers that at present seem to limit the increasing adoption of RegenAg practices in Australia as well as identifying the opportunities that exist for RegenAg going forward. Unsurprisingly, our FCM highlights the complexity of this issue, the various scales at which change needs to happen, and the multitude of relationships and actors that need to be involved. Our analysis showed that our stakeholder group, as a pro-RegenAg group, is aware of these complexities, and we were able to work together to demonstrate this understanding. While we did not include any ‘voices’ from conventional agriculture, this understanding is a useful entry point for those promoting more sustainable practices in Australian agriculture and offers a platform for outreach to different, even ‘opposing’, voices.

From the analysis of the FCM, we are able to make suggestions about variables and relationships of interest. Our centrality analysis highlighted several key variables, and these are ‘

Institutional Reticence to Adopt and Educate’, ‘

Valuing Natural Capital in Multiple Dimensions’, ‘

Cost of Converting to Regenerative’, ‘

Gov’t Policy Discourages Regen Ag’, and ‘

Lock In’ of Farmers with High Debt Levels”. However, for us, the promise of FCM was in its ability to serve as a ‘boundary object’ around which our discussion of RegenAg adoption could be mediated, negotiated, and navigated. As we built our model, using MURAL and Zoom, the ‘visual’ nature of the process helped us to represent the connections between abstract concepts, any of which could be changed by proposals from any stakeholder [

93]. Used in this way, our FCM, in keeping with the literature, helped stakeholders to: (1) create a shared language, allowing for diverse knowledge and different disciplines to work together by creating a ’model’ together on MURAL and in iterations afterwards; (2) clearly identify points of difference or similarity of relationships within and between stakeholder mental models; and (3) “transform their current collective knowledge toward an agreement of facts through discussion, negotiation, and careful scrutiny of what they know” to move towards innovation, cooperation, and consensus building [

94,

95,

96]. PM and the process we used provided a model by which we could encourage individuals to share their perspectives on a collective issue of interest, forming an explicit group mental model as the object around which the discussion could be mediated [

75,

97,

98]. Even if stakeholders did not completely agree with the model, it is more difficult to ignore the model “because they built the model themselves” [

43,

99].

We complemented this use of the model as a boundary object with the development of ‘narratives’ to report the findings of our FCM in a way that facilitates the communication of complexity of this issue and the system(s) it involves. While each ‘narrative’ is a simplification of reality, the presence of multiple stories actually allows us to embrace complexity and to communicate it [

63,

64,

100,

101]. By showing a number of possible, plausible narratives, we demonstrate that there is more than one way to see and interpret the system, helping participants to acknowledge that their interpretation is not the only one. Even if valid, their chosen narrative is probably imperfect or incomplete. As such, we consider narratives as an instrument to communicate complexity that is constantly evolving and under construction, aligning with the iteration so desired and so necessary in an overall PM process. In short, FCM creates a visualisation, and together with the accompanying reporting and communication of the results as narratives, this process of model building with stakeholders makes the complexity of this system starkly apparent. Recognition of that complexity is the first step to finding the leverage points needed to transform that system [

68].

5.3. Limitations

While the findings of our study build on work in RegenAg and contribute to PM in several ways, there were also limitations. Being limited to one case study and one workshop meant that a cross-case analysis was not possible. No PM, even with the same stakeholders, is the same, and this makes the presence of a ‘control’ group impossible. However, a workshop similar in intent with different stakeholders could have been interesting. In a similar fashion, a workshop focused on a different topic (for example, groundwater usage) could have provided additional insights and comparisons between how different workshops were both run and received and what insights were produced as a result. For example, for this workshop, we introduced two possible metrics before the workshop. While neither was ultimately chosen as the metric of the system, this may still have introduced bias by framing the conversation.

Additionally, this study was intentionally absent of conventional agriculture producers. While a purposeful choice to minimise disruptive and destructive conflict, those ‘voices’ were not considered in our depiction of the ‘barriers’ of RegenAg adoption. Indeed, the workshop was based on the assumption that more RegenAg is desirable, to which not all farmers might agree. However, the presence of a largely homogenous, pro-RegenAg group did allow for us to notice some of the in-group distinctions and conflicting perceptions. We stand by the decision to proceed as we did, but transparency dictates noting this absence, and future work can and should find ways to include more ‘conventional’ participants, which could add more representativeness and complexity to our FCM. Another consideration for our group was who was left out by the move to virtual. It was a necessary move under conditions of social distancing imposed by the pandemic, but it did exclude those without internet access or the skill, and it may have even limited full participation from our participants who may have struggled to navigate the new technology. These limits should be considered and accounted for in future studies of virtual PM.

Our small sample size also did not allow for a ‘full’ representation of RegenAg, as it is not a homogenous group. RegenAg is an umbrella, covering a variety of practices and outcomes [

27], and working with a different group of participants may have led to a different model. The small sample size also limits the degree to which statistical analysis can find ‘significance’ in the strength of relationships on our model. Future work could combat this by creating individual maps with participants before aggregating into a larger ‘group’ map or a separate larger group discussion. We could not take this approach with our limited time and resources, but we hope to do so in the future. In addition, sample size is a pervasive issue in PM, but it is one that has the potential to be overcome with virtual facilitation (even beyond COVID-19), as shown here. Under normal circumstances, COVID-19 and social distancing restrictions would have made this engagement impossible, but we managed to pivot to a successful virtual delivery under lockdown, and that same method could be used to expand sample sizes as geographical distance or the physical size of the room are no longer limiting factors.

5.4. Future Research

Notwithstanding the above limitations, our case study suggests important areas of future development and research. The first is that for those seeking to increase RegenAg, we should further investigate the narratives presented along with their accompanying solutions to ascertain if they are ‘true’ in the eyes of stakeholders and in reality, as ‘truth’ in one does not guarantee ‘truth’ in the other. Our aim is for narratives to be the best representation of reality we can have at a certain point in time given the information available. A good narrative should be accepted by as many stakeholders as possible, meaning that the narrative speaks to multiple perspectives, and possess multiple, legitimate sources of corroborating evidence. This entails examining the relevant variables and their relationships to ascertain if available evidence supports their existence. For example, for Narrative 1: ‘Government First’, to determine to what extent “Government policy discourages RegenAg”, a policy ‘wish list’ of RegenAg stakeholders could be created during a follow-up a PM workshop, online or offline iteration (Google Docs, email, etc), or by compiling and synthesising reports from various interest groups—this could be compared to current policy to identify where the gaps are and what is needed to address them. Bespoke follow-up activities could be implemented for each of the narratives, involving stakeholders at various stages to further advance and solidify the opportunities identified during the initial engagement.

Second, our study suggests that the use of FCM (or any PM technique) in a virtual format should be explored further, particularly considering the current COVID-19 contingency. Stakeholder engagement during the COVID crisis offers a unique opportunity to benchmark remote facilitation designs against face-to-face workshops, with the aim of providing general recommendations on when either method would be preferable (e.g., depending on problem situation, level of stakeholder conflict, types of SES resources involved, etc.). However, it is also worth noting here who may be excluded by such a move to virtual, including those without the internet access or technological skills needed to successfully participate in this online format. Based on the experience of the activities conducted as part of this case study, a virtual approach has the potential to offer benefits in coordinating participatory processes of large stakeholder groups spread over vast geographical areas, which may be useful in many other SES issues.

Previous studies using FCM often begin with individual maps before aggregating to a larger collective map, usually over the course of several meetings [

43,

47]. We did not draw individual models with stakeholders one-on-one, instead waiting to develop a full group map in one sitting due to our time constraints imposed by the pandemic, with individual follow-up as needed. While not inherently a negative approach, it is interesting to note the difference and the possibility of further depth and complexity of the FCM presented by iterations between individual maps and collective maps, depending on where the starting point may be. The use of our ‘narrative’ templates (story, actors, model, solutions) may be an alternative way to guide this process, collecting stories beforehand (which can be accompanied by individual cognitive maps) and then iterating these narratives side by side with the main FCM over the course of PM. Logic Models—a framework for charting the links between a project’s resources, activities, and outputs and its intended outcomes—could also be used to better structure and sequence the activities needed to build FCMs.

Finally, to develop a full picture of the dynamics people bring into any participatory or PM workshop, we should further explore the idea of what would constitute an ideal ‘enabling’ environment of PM (i.e., specify the articulation of tools, facilitation techniques, communication strategies, and follow-up activities that should be implemented to deliver on the promises of PM) and its ability to construct and manage PM as a socio-emotional system from which to elicit and transform individual mental models. This aspect of PM is often missing from reporting on PM, which tends to focus on the model. The dynamics of the emotions and social structures that stakeholders bring with them into a workshop holds implications for the way we conduct PM, the way we report the findings, and the way we seek to address issues of SES (such as increasing the adoption of RegenAg practices). ‘Narratives’ seem to be one of many possible tools that can assist in the PM process, as it can effectively align the insights developed from a scientific modelling exercise with the ways people best assimilate information. Similar to narratives, there are likely to be other tools out there, and we should look to further explore how concepts, ideas, and practices from various behavioral sciences can improve any aspect of the design, practice, or evaluation of PM—so that it is behaviorally attuned to the problems that it is trying to solve.