Abstract

Geotourism is one of the fastest growing tourism branches. Geoparks feature prominently in geotourism as well as geoeducation. Well-designed geotrails link local geology, geoheritage and geoeducation. Unfortunately many trails do not consider or insufficiently acknowledge recent didactic and touristic findings. As a result, they fail to interest a lay audience in geological phenomena, convey relevant information, and attract tourists to the region. A catalogue of state-of-the-art criteria for the evaluation of existing geotrails based on a case study of the UNESCO Global Geopark Swabian Alb (Germany) was elaborated by a comprehensive literature research and subsequently verified on the basis of selected model trails. Finally, recommendations for model geotrails were derived. The term “model” refers in this case to aspects of geoeducation as well as geotourism. Results showed considerable enhancements, but also the further necessity of improvements such as a stronger consideration of Education for sustainable Development (ESD), a better integration of the criteria of geo-interpretation as well as the opportunities and potentials offered by the to-date too scarcely used new technologies. Our surveys in the UGGp Swabian Alb largely coincide with the results of national and international research. Often it is merely small factors that differentiate an adequate and a model geotrail. Our checklist of criteria offers a good basis for these factors.

1. Introduction

Geotourism, long considered a form of niche tourism [1], has recently become a very popular form of themed tourism [2,3,4,5,6,7]. Over the course of the past decade, it has been one of the fastest growing branches of tourism [8]. A prominent feature of geotourism has been geoparks [9,10]. These parks contain outstanding geological heritage, and it is therefore vital that they formulate a sustainable regional development strategy [11]. In particular, the UNESCO Global Geoparks should establish themselves as model regions for sustainable development and enable both inhabitants and visitors to get to know and appreciate what is special about their region. They should furthermore reconcile the need for conservation and innovative economic development [12].

“Education at all levels is at the core of the UNESCO Global Geopark concept” [13]). This educational work is essential to convey an understanding of the need for comprehensive protection of geoheritage. Different educational concepts and instruments can be used for this purpose. At the same time, some of these instruments can also serve as important geotourism opportunities and thus can contribute to regional economic value creation. A frequently chosen mediation tool is a wide variety of trail concepts (educational and experience trails) [7,14,15,16]. Well-designed geotrails link local geodiversity, geoheritage and geoeducation, which makes them highly attractive for geotourism. Unfortunately many trails do not take into account at all or not sufficiently recent didactic and touristic findings. As a result, they fail both to interest a lay audience in geological phenomena and to convey relevant information, and to attract tourists to the region.

Our case study, the UNESCO Global Geopark (UGGp) Swabian Alb, located in Southwest Germany, is one of the oldest geoparks in the world [17] and features a significant number of geotrails of various types. Within the framework of a small research project, a catalogue of state-of-the-art criteria to evaluate existing geotrails was elaborated on the basis of a previous SWOT-Analysis, comprehensive literature research and subsequently verified on the basis of exemplarily selected trails in the Geopark Swabian Alb. Finally, recommendations for model geotrails were derived (Section 2.4.3). The term “model” refers in this case to aspects of geoeducation as well as geotourism. The results of the research project will hopefully provide guidance to geoparks and other institutions. Additionally, the tools to design such trails and to maintain high standards are included.

In the following article, the theoretical background of geotourism, geoparks and especially geotrails as well as geoeducation and trail concepts in general are presented. The UGGp Swabian Alb is briefly characterised as a case study before the results of the field research are presented following an explanatory chapter on methodology. The results are contextualised with statements from (inter-)national literature and suggestions for model geotrails are presented for discussion.

2. Theoretical Background

Geotrails are a geotourism module that can be found both inside and outside of geoparks. It is therefore vital to discuss the theoretical background of geotourism, geoparks and geoeducation before a comprehensive analysis of geotrails in international literature is provided in order to ensure better classification. Due to the focus of this article, geotourism and geoparks are presented rather briefly and compactly, while geoeducation and especially geotrails are dealt with in more detail.

2.1. Geotourism

The term ‘geotourism’ was coined by Hose [18]. It was triggered by the planned destruction of the Bilston Burn gorge near Edinburgh, a famous geological outcrop that the local authorities had classified as an “ideal site” for a landfill [19]. For the first time in the German-speaking world, Frey [20], one of the initiators of the Geopark movement, used the term geotourism. While Hose [1] long considered geotourism as a form of niche tourism, it has since evolved into a form of in-demand thematic tourism [2,3,4,5,6,7]. In the last decade, geotourism has established itself to be the fastest growing tourism sector [8].

The definition of geotourism ranges from very narrow interpretations as “tourism focused on geological features” [21] to very broad ones in which a separation from other forms of tourism such as nature or ecotourism becomes difficult: “tourism that sustains or enhances the geographic character of a place, its environment, culture, aesthetics, heritage, and the well-being of its residents.” [22]. Meanwhile, geotourism is defined as “a form of natural area tourism that specifically focuses on geology and landscape. It promotes tourism to geosites and the conservation of geo-diversity and an understanding of Earth Sciences through appreciation and learning. This is achieved through independent visits to geological features, use of geo-trails and viewpoints, guided tours, geo-activities and patronage of geosite visitor centres” [4]. Geotourism activities do not only concentrate on geotopes, but also on a broad spectrum of topics relating to the history of the earth and its landscape including interactions with vegetation, fauna, cultural landscapes and anthropogenic uses such as the extraction of raw materials and the history and development of building and construction culture.

Geotourism serves as an instrument of sustainable regional development. It must ensure the protection of geotopes and convey an awareness of this through geoscientific environmental education [7] (25f). Some international definitions of geotourism explicitly include this educational mission, such as Hose [21]: “… the provision of interpretative and service facilities for geosites … by generating appreciation, learning and research by and for current and future generations” as well as Dowling and Newsome [4] (see above). Both definitions emphasise the necessity of geo-interpretation, indeed the latter explicitly mentions the term geotrails. Geoparks (see Section 2.2) are the most important vehicles of geotourism worldwide. In 2011, the European Geoparks adopted the Arouca Declaration, which defines the cornerstones of the desired sustainable geotourism activities [12].

2.2. Geoparks

Although the term may suggest otherwise, geoparks are not legally protected areas, but rather a designation for regions that possess scientifically valuable and rare geopotentials. However, exceptional geoheritage alone is not sufficient; recognised geoparks must have a strategy for sustainable regional development, scientific research and environmental education. In addition to clearly defined boundaries, an economic development potential has also to be demonstrated. Regions that have exceptional geopotential, but no or hardly any opportunities for sustainable regional development, e.g., due to their remoteness or small size, cannot be recognised as Geoparks. The desired economic development has so far been implemented mainly through geotourism modules. Furthermore, it is crucial to extensively involve the inhabitants of the geopark in the regional development (bottom-up approach) as well as the exchange with other national and international geoparks within the framework of intensive networking activities. While geoheritage represents the determining foundation, geoparks must ensure its preservation [12]. This can be achieved, for instance, through educational work in the context of geoeducation and environmental education as well as education for sustainable development (ESD). Geoparks thus promote geotope protection as well as geotourism and geoeducation [3].

Geoparks are a relatively recent phenomenon [10]. By the late 1990s, problems associated with an earlier form of geologically motivated travel had become virulent. Tours to fossil and mineral sites offered to a specific demand segment were sometimes accompanied by the looting of the visited destinations [7]. This affected, for instance, the réserve géologique de Haute Provence (France) and the Petrified Forests of Lesbos (Greece). These four initiators (including also Gerolstein/Vulkaneifel (Germany) and the Maestrazgo Cultural Park (Spain)), supported by the EU LEADER programme, started the Geopark movement with the objectives of protecting the geological and geomorphological heritage and promoting sustainable regional development in their respective areas [23]. In 2000, the European Geoparks Network (EGN) was founded. Eighty-eight European Geoparks from 26 European countries currently belong to this network [12].

Just one year after its foundation, the European Geoparks Network signed an agreement with UNESCO to place the network under its patronage. In 2015, in addition to the already existing World Heritage Sites (World Cultural Heritage, World Natural Heritage, Biosphere Reserves), a further category was introduced with the UNESCO Global Geoparks (UGGp) [11]. As model regions for sustainable development, the UGGp are to manage conservation, education and sustainable development with a holistic participatory bottom-up approach and enable both their inhabitants and visitors to participate in this process, to learn to know and appreciate the potential of the region and ultimately to build up a regional awareness. As innovation regions, UGGp should reconcile conservation and economic development needs [24]. The UNESCO programme has encouraged numerous countries to draw up corresponding development strategies [25]. Currently, 169 UGGps are recognised in 44 countries [11].

Thanks to the international movement and the increasing interest in geotopics, the BLA-GEO (the German Federal-State Soil Research Committee) established the “National GeoPark” seal of quality for Germany. In 2002, the Alfred Wegener Foundation awarded this title to the first four German geoparks. There are now 18 National GeoParks in Germany, including seven that have also been designated as European and UNESCO Global Geoparks [26].

Both nationally and globally, the geopark movement is characterised by a very high level of dynamism, so that new areas are regularly designated as geoparks. In contrast to large, protected areas, all geopark categories are subject to regular evaluations, both nationally and internationally, which can also lead to the withdrawal of the designation if necessary. These evaluations thus guarantee a high degree of fulfilment of the designation criteria.

2.3. Geoeducation

Geoeducation is understood as the teaching of geo-scientific facts. This can take place both formally, i.e, integrated into curricular teaching structures (schools, universities), and informally, i.e., extra-curricular to a lay public, usually in the context of leisure activities. Since geotrails are mainly used by a lay public, they belong to the category of “informal education” (see Section 2.3.1).

Geoeducation is considered a part of environmental education and education for sustainable development (ESD), which creates holistic access to geoscientific knowledge, geotourism opportunities, but also to geotope protection and regional awareness [27]. ESD and geoeducation are the basic prerequisites for generating awareness of the geological heritage and its interactions with the natural and cultural heritage and for preserving this heritage for future generations.

Geoparks offer a good platform to combine geoscientific education and public relations and thus counteract the “education or knowledge deficit” [15]. Ref. [28] see geoparks in the educational context as “highly effective tools” that communicate geoscientific aspects to children in an experience-oriented way and thus offer a great opportunity to promote geosciences in their entire breadth. Education is therefore one of the three main functions of the UGGp [13]: “Education at all levels is at the core of the UNESCO Global Geopark concept. From university researchers to local community groups, UNESCO Global Geoparks encourage awareness of the story of the planet as read in the rocks, landscape and on-going geological processes. UNESCO Global Geoparks also promote the links between geological heritage and all other aspects of the area’s natural and cultural heritage, clearly demonstrating that geodiversity is the foundation of all ecosystems and the basis of human interaction with the landscape.” For visitors, geoparks are “centres for informal education providing tourists with informative and enjoyable experiences which enhance their appreciation of the landscape and culture” [12]. The informal communication of knowledge is ensured through a variety of media including museums, visitor centres, guided tours and geotrails.

Since 2015, the 2030 Agenda with its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (UN A/RES/70/1) has provided a framework within which UNESCO Geoparks work. SDG 4 “Quality education” was ranked as the most important SDG by the European Geoparks [29]. 62% of Geoparks have an education department and 37% develop education services for schools [30]. Although education is generally highly valued in the geopark community, there is still a considerable need for research. Only 15.7% of all scientific articles on geoparks in the period 2002–2018 examine geoeducation and geotourism and another 11% consider sustainable development and geotourism [31].

Geoeducation is not only a fundamental task of all categories of geoparks.. it is, above all, an important tool to generate interest in geo-topics and thus geotourism offers as well as encourage an awareness for the geological heritage and geotope protection [27]. Comprehensive geoeducation opportunities are also urgently needed as lay people usually lack basic knowledge of geology and geomorphology [32].

Geoeducation has been severely neglected for a long time, especially in Germany. On the one hand, there was only a very rudimentary to almost no integration into the formal school curriculum [28] and, on the other hand, communicating geoscientific topics to the general public was long considered “unscientific” [33]. As a result, comprehensive geoscientific research was hardly perceived by the population, which means that general geoscientific education and knowledge about the importance of geosciences for the most diverse aspects of life (environmental protection and nature conservation, handling of natural resources, etc.) are still very insufficiently disseminated as of today [34].

2.3.1. Informal Geoeducation for a Casual Audience

Informal or extra-curricular education is aimed at a casual audience. The motivation for participating in guided activities or for taking part in self-guided activities differs fundamentally from formal educational activities. While curricular forms of delivery are strongly supported by extrinsic motives and participation is usually compulsory, a lay audience in a casual or recreational mood has intrinsic motives.

For “recreational learning”, specific concepts that clearly differ from school-based environmental education as well as professional implementation are decisive, which adequately take into account the specific expectations and requirements of a casual audience [35].The main motive of a recreational audience for spending time in nature and landscape is predominantly in the recreational and tourism sector. Simply reading a brochure can be perceived as “work” in the casual mood [36]. Recreational learning is therefore only accepted if the expected benefits exceed the predicted effort, i.e., sparks and maintains interest and/or promises to be fun [37]. In order to reach a casual audience, the recreational learning must therefore focus on experiences, discoveries and playful aspects in direct connection with the phenomenon [36]. In principle, guests who spend time in geoscapes are interested in discovering the landscape and understanding its history [38,39]. In protected areas, this can also be an intrinsic educational interest, as population groups with higher education or a pronounced interest in nature topics are often disproportionately represented here. Surveys by [40] at three geosites in southern Switzerland showed that the vast majority of tourists were primarily interested in information about the site, in particular about fauna and flora as well as landscape and geology. In the latter case, there was great interest in the development of the landscape and in understanding the different forms of relief, followed by more geological topics such as rocks or the formation of the Alps. Those who were not interested either thought they were already sufficiently informed, felt that nature did not need to be explained or wanted to be left alone. However, the potential demand volume is often latent, i.e., visitors are interested in principle, but do not necessarily visit a corresponding place due to this [38]. In order to reach this audience, their attention must be stimulated through visual, emotional or linguistic elements [41] and then subsequently maintained. Essential here are the criteria of heritage interpretation developed in the USA at the end of the 1950s [42,43,44]—a methodical-didactic approach to communicating nature and landscape to a casual audience. Through interpretation, an understanding is achieved, leading to appreciation and ultimately protection [45]. Below are the decisive aspects of landscape interpretation, which distinguish it from the purely receptive information transfer of traditional nature trails, guided tours and other forms of recreational learning and education:

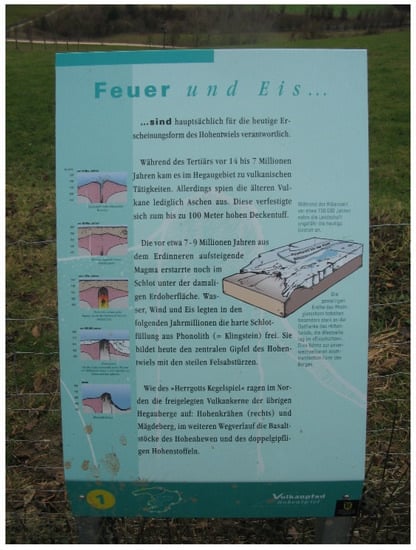

Arouse interest (“provoke”): Since a casual audience, in contrast to a professional audience, cannot be assumed, per se, to have a pronounced interest in educational content on environmental and nature topics, the educational activity must overcome the attention threshold of the potential participants. This can be ensured by a unique temporal or spatial setting, a surprising visual design or a headline that generates curiosity (see Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Panel allowing a view of the marsh behind it (South Tyrol, Italy) (Megerle 2002).

Figure 2.

Board with an unusual visual design (Les Rousses, Jura, France) (Megerle 2022).

Case study: The Illgraben information post in Susten (Switzerland) (Figure 3) illustrates how latent interest can be addressed, how easy access to the content can be created, and how different information [46,47] needs can be addressed: Susten is located in the Pfyn-Finges Regional Nature Park. An extremely dynamic debris flow system is active in the municipality (several debris flows per year), which has long been monitored for research and warning purposes [48]. The Regional Nature Park, in cooperation with the municipality and the tourist office, wants to use the information post to sensitise visitors and locals—including many newcomers—to this geomorphological process and the correct way to deal with debris flows. The information post is located on the heavily frequented station square. With an imposing stone block from the Illbach, a replica of an alarm station and a telescope, three foreign objects surprise passers-by. The deliberately placed small-format panels, supported by generous illustrations and short texts, convey the basic content. The direct reference to the Illgraben is established by the stone block and a telescope, which allows direct observation of the erosion funnel. The panels also mention that further information is available at the adjacent tourist office if interest is generated [35].

Figure 3.

Illgraben Information post (Susten Switzerland) (Bureau Relief).

Discover connections and hidden meanings (“reveal”): Many characteristics (“hidden meaning”) of a landscape are not immediately obvious to guests who have no prior professional training. For example, the mostly overlooked and nowadays little known meadow ditches (Wiesenwässergräben) can be used to convey a comprehensive historical-genetic cultural landscape development. This also helps to build an emotional relationship to a landscape as well as a regional awareness, as beyond a purely affective approach, much deeper impressions are created in conveying an understanding of the relationship between the environment and the cultural efforts of man [49]. This applies analogically to scientific contexts, such as the forms of extinct volcanism in the UGGp Swabian Alb, which a layperson would not have perceived as a special feature ([50], Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Tertiary volcanic vent Calver Bühl. Not recognizable as such by a lay audience (UGGp Swabian Alb, Germany) (Megerle 2020).

Establish references to the concrete phenomenon and the guest (“relate”): Interpretation sites always refer to a phenomenon that is perceptible to the guest and its specific characteristics at a respective location. Communication is intensified by the reference to the visitor’s life-world. Instead of generalities, an interpretation site focuses on regional, local and individual specifics features (see Figure 5). References between geological, biological and cultural heritage should also be shown [45]. Surveys by [38] showed that visitors wanted an interpretation of the specific site they were visiting and “not an introductory lecture on geology”.

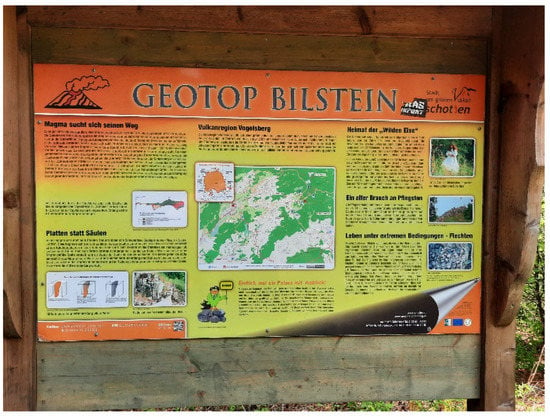

Figure 5.

Panel with regionally specific references. National Vogelsberg Geopark (Germany) (Megerle 2021).

Target group orientation and overarching theme: Interpretation sites must take into account the most important characteristics of the target audience in terms of expectations, physical and cognitive abilities, as well as previous knowledge of the topic being conveyed [38]. Families are a challenging audience in this respect as children and adults have different needs and demands [42,47]. Short, stimulating texts that are easy to understand for the respective target group are an essential aspect of interpretation. The use of technical words as well as unfamiliar vocabulary or complicated sentence structure in general creates a diction distance. Differences in text comprehension are also often underestimated. For example, a sequence that is comprehensible to an expert can cause difficulties for a layperson [51].

In order to facilitate the guests’ categorization and thus memory of the interpretation, the formulation of an overarching theme is crucial as “people remember themes—they forget facts” [43]. Individual installations (nature trail), but also a whole geopark can be based on a key theme. The latter is the case with the UGGp Erz der Alpen (Ore of the Alps), which has the key theme of (pre-)historical mining in its name and consistently maintains it with touristic activities such as the four-day Copper Ore Trail [52].

Interpretation can sometimes be seen as an (over)simplification [53]. However, this is not the case with professional presentation. Here, it is rather a matter of re-contextualising the information in order to convey it in a way that is appropriate for the target group.

The above-mentioned basic principles of heritage interpretation can be applied to all guided or self-guided forms of geoeducation. The major challenge in geoscientific environmental education is the following [54]:

- To spark interest in a topic that is commonly considered less interesting.

- To maintain interest throughout the entire course and ideally arouse it for further activities.

- To break down the sometimes very complex topics to a generally understandable level with-out making them too banal.

- To convey topics for which no or only little previous knowledge can be assumed.

- To make the large dimensions of geology comprehensible in terms of space and time.

Even if geoscientific facts have to be simplified to some extent, the scientific correctness of the information conveyed must be maintained. In addition to “traditional” forms of communication via texts, panels, etc., innovative, rather unusual and increasingly digital forms of communication can be used. In this way, target groups can be reached that are not addressed by “traditional” forms.

2.4. Geotrails

Informal geoeducation takes place through a variety of media and with guided as well as self-guiding touristic activities inside and outside of geoparks. Trails in various forms are the most common form of self-guided offerings that allow visitors to discover and experience (geo)potentials on their own are the most widespread geotourism activities [14].

“Traditional” nature trails have been used for almost a century to inform visitors on site about certain phenomena by means of panels [55]. A characteristic of a nature trail, which distinguishes it from the experience trail, is the purely receptive transfer of information. The objectives of nature trails were primarily educational, guiding and informative [55], but they were also increasingly seen as a tourism product [16]. Traditional nature trails are still the most widely used type of trail today.

In contrast to traditional nature trails, visitors are actively involved in nature experience trails. This is achieved either through appropriate installations (e.g., viewing tubes), interactive panel elements (ring binder panels, folding panels, etc.) (see Figure 6) or verbal instructions. Special emphasis is also placed on motor and sensory skills [16].

Figure 6.

Nature experience trail with interactive station. Stockach Spring Experience Trail (Germany) (Megerle 2001).

Discovery trails often work with brochures or digital guidance and little to no installations in the field. Visitors are made aware of phenomena and encouraged to look closely and think.

A geotrail can be defined as “A usually way-marked guided or self-guided route around a geo-ogical and/or geomorphological site on which points of interest are indicated and explained” [14]. For the purposes of our article, we will refer to a trail as a geotrail if the majority of its stations deal with geoscientific topics. In Germany there are trails that are exclusively related to geopotentials (e.g., geological nature trail in the Kirnbachtal near Tübingen), but at the same time there are many trails that integrate geoscientific topics as well as other aspects.

The first geotrail was a geological theme park in South London in the middle of the 19th century. Most geotrails, however, were created in the 1970s [14]; in Germany, the first geotrails were also created in this period [56]. The Keuper nature trail in the Kirnbach valley in Tübingen, which was developed by geoscientists of the Geological Institute situated there, was a pioneering example. Along with the overall significant surge of trails, geological trails were increasingly installed in the following decades, and individual geoscientific aspects were integrated into nature trails.

Nevertheless, geotrails are still—in contrast to nature in general or forest trails—clearly in the minority. A survey of nature trails in Germany conducted in the late 1990s showed that of the then 660 trails, only about 20, or 3%, dealt with geology [55]. Eder and Arnberger [57] analysed a total of 690 trails in Austria. Geotrails had a share of 8.6%, supplemented by 4.2% that included the topics of mining and industry. However, it is not always clear how the criteria for classification as a geotrail are determined. In the UGGp Swabian Alb, for example, some trails designated as geotrails had (significantly) less than 50% of the stations with geoscientific content (see Section 5.1).

Barefoot trails are a special form of trail that can be integrated into nature discovery trails as a small variant or implemented as independent trails of 2 to 3 km in length. Barefoot trails focus primarily on the sensory experience of different soil and stone materials, rather than on conveying landscape content. New approaches are thematic barefoot trails, which combine sensory experience with content mediation.

While the majority of geotrails are designed for pedestrians, there are also occasional opportunities for cyclists (e.g., in Great Britain] [14]. Some geotrails are offered specifically for mountain bikers, in the case of rough terrain (e.g., UGGp Sierras Subbéticas) [58], and others that can also be used by those with limited mobility (e.g., Geopark Sierra Nzorte de Sevilla) [58]. A special feature are car trails, as they are offered e.g., in the USA and Canada. Roadside geology guides convey the essential geological aspects of a state, for example, and can be covered in about one day with various stops [59]. In Morocco, two very long auto trails have been designed. At 270 km, Geotrail A from Dakhla to Awsard, which crosses various Sahara landscapes, is certainly one of the longest of its kind [60]. France’s UGGp Bauges offers the first self-guiding cave trail [61], while Spain’s Cabo de Gata Geopark has designed a “submerging” marine geotrail [58].

While most of the trails are relatively short (2–3 km) and easily manageable by families in a few hours, there are also multi-day geotourism themed trails, such as the four-day Copper Ore Trail in the UGGp Erz der Alpen (Ore of the Alps) (Austria), which connects various montane-historical sites [52].

“Traditional” (educational) trails predominantly work with different types of text panels in the field. Increasingly, however, interactive elements that actively involve visitors are also being integrated. More recently, this has been extended and supplemented by various types of digital technologies (see Section 2.4.2). In order to reduce “furnishing” the landscape with numerous signs, the mediation for some geotrails is carried out via brochures. At most, small numbers are found in the terrain. Newer developments here rely on QR codes or the use of tablets.

Self-guiding trails can be supplemented with additional activities. For example, a brochure was prepared for the Spring Experience Trail in Bad Herrenalb, which contains additional activity suggestions and is intended to enable group leaders, in particular, to prepare a tour of the trail. In addition, guides were trained to offer guided excursions along the trail, mainly for school classes. For younger children, for whom most of the stations were too demanding, appropriate stations were integrated and a quiz was developed, for which a certificate as a spring researcher is available after successful completion [62].

Geotrails are realised within, but also outside of geoparks and thus serve for diversification of tourism. Simultaneously, they take on an important task in the field of informal geoeducation.

2.4.1. Critical View of the Various Trail Concepts, with Special Emphasis on Germany

After a prolific educational trail boom in the 1970s, critical voices were increasingly heard in the 1990s. More specifically, the often didactically insufficiently prepared texts (Figure 7) and the offer of “ready-made” nature trails, which often could be found without any local reference in the whole of the Federal Republic of Germany, raised justified doubts whether the conventional nature trails could meet the expectations placed on them. Studies [15,55,63,64,65] confirmed these concerns. For example, only 9% of the people surveyed on traditional nature trails in Bad Herrenalb had taken note of all the panels. Some people had not even registered that they were on a nature trail [64]. In the Geoparks Bergstraße-Odenwald and Vulkaneifel, 14% of those interviewed on geotrails had not noticed the panels. Of those who had noticed the signs, 40% had not read them or had read them only rudimentarily. The reasons given for this were “lack of interest” and design features such as “too much text” or “we already know”. Those who had read the signs found them predominantly informative and attractively designed. However, only 5% of the visitors had come to the geoparks for the educational sites [15]. Similarly, in the Altmühltal, the nature trails were not sought out specifically, but were used as hiking trails. The “experiential value” of the nature trails and their attractiveness for families was rated low [63]. The nature trails also proved to be less successful in terms of environmental education. Even people who had demonstrably read the panels could not remember the contents two hours later, as studies in the Bavarian Forest National Park showed [66]. Due to the purely receptive transfer of knowledge, the “traditional” nature trails also did not succeed in conveying a value for the natural phenomena to the visitors and thus motivate them to work for the preservation of these phenomena.

Figure 7.

Traditional nature trail panel with too much text (Geopark Vulkaneifel, Germany) (Megerle 2011).

The main criticisms of traditional nature trails are briefly summarized as follows: no definition of a target group (a nature trail for everyone does not do justice to anyone), no local reference (the nature trail could be located anywhere), inadequate implementation (technical vocabulary, no story-telling), lack of guidance systems both to the trail and about the trail, no explicit entrance sign, lack of maintenance, lack of marketing and no embedding in the overall educational offering of the region [67]. One of the “most common mistakes of existing trail projects” was the lack of information and maps to find the trail as well as insufficient markings along the trail [68]. A lack of wayfinding signs along the trail can lead to “trip stress” [69] and thus visitor frustration, as can inadequate signage to the trail entrance station.

After the first positive reactions to the then innovative nature experience trails, they were realized on an almost inflationary scale, often with recourse to “tried and tested installations” such as tree telephones, barefoot paths or wooden xylophones, which were used on a third to half of the trails. This results in an increasing levelling towards “standard paths”, which in turn can lead to a decreasing interest of the visitors due to the uniformity and the oversupply [16]. Another problematic area was the concept of “experience”, which is both ambiguous and difficult to define. The high subjectivity of the term makes it impossible to meet uniform standards for different target groups and different spatial and temporal references. It can therefore prove problematic if the ill-considered use of the buzzword “experience”, often for pure marketing reasons, raises high expectations among the intended participants that cannot be satisfied due to the concrete design. This can lead to a high degree of frustration as well as to a rejection of similarly designated trails [37]. Examples of the thoughtless use of the term “experience” are so-called nature experience trails, which largely correspond to traditional nature trails with purely receptive text panels and only one or two interactive stations without an underlying overall concept. Trails where the only activity of the visitors is to turn the pages of a ring binder of a purely receptive text are only slightly better. Some nature experience paths failed to communicate even a minimum of information at well over 50% of the stations. Although such trails can be entertaining, they can no longer be considered a medium for geoeducation [16].

2.4.2. Further Development of Geotrails

Analogous to the points of criticism presented in Section 2.4.1, numerous weaknesses were also found in geotrails, so that they could not meet the expectations placed in them, or not to the desired extent. This was particularly true of the following aspects:

- Visually unappealing panels with an excessive amount of text, which usually did not provoke any interest in actually reading the panels (see Figure 7).

- Use of scientific-technical language that was difficult or impossible to understand for a lay audience.

- Example text of a nature trail plaque from Schramberg in the Black Forest [70]: “Upper Rotliegend Group: Of the over 500 m thick Rotliegend found here, about 370 m is accounted for by the Upper Rotliegend Group. These deposits originate from the Rotliegend period 245 to 225 million years ago and consist of debris of granite, gneiss, granite porphyry and other basement rocks, as well as quartz porphyry and silicified porphyry tuffs from the Middle Rotliegend.”

- Lack of target group orientation (e.g., trails for families with children with unsuitable texts and installations that were not accessible for children) (see Figure 8)

Figure 8. Station clearly too high for the target group of children (Spring Experience Trail, Stockach, Germany) (Megerle 2001).

Figure 8. Station clearly too high for the target group of children (Spring Experience Trail, Stockach, Germany) (Megerle 2001). - Lack of regional reference (see Figure 9): A panel in Titisee-Neustadt (Black Forest) with textbook style knowledge on springs using a picture of another continent in a location where there is no spring.

Figure 9. Panel without any regional reference (Titisee-Neustadt, Germany) (Megerle 2001).

Figure 9. Panel without any regional reference (Titisee-Neustadt, Germany) (Megerle 2001). - Lack of reference to the everyday world of visitors.

- Missing central idea and take-home message.

Due to extensive research results in the field of geoeducation as well as geotourism, clear developments in the textual and graphical design of the panels, the integration of new media, the involvement of the visitors and the consideration of the criteria of heritage interpretation can be seen in the last decades.

In recent years, the use of digital technologies in (informal) education also has been on the rise. Apart from offering different levels of information via QR code or texts in other languages without overloading panels, virtual realities, interviews with contemporary witnesses, etc. can be included [71]. Moreover, this is more likely to reach younger and new target groups [14]. In addition to numerous advantages, digital technologies also have a number of disadvantages. These can include the sometimes-high costs of programming virtual realities and the terminal equipment required for optimal presentation; the necessary expertise, but also vandalism or weather damage if the corresponding facilities are located outdoors. QR codes as a relatively low-threshold digital possibility to offer additional information have failed on site due to insufficient network availability and possibly due to aversions of certain target groups (e.g., older people) to work with technical devices in nature. While for many, especially younger people, the use of digital media is a matter of course (“digital natives”), this is not the case for many, especially older people, so that they are excluded by corresponding installations. This is equally true for people who do not have the corresponding end devices, e.g., for financial reasons.

For the realization of geotrails, a procedure as shown in Figure 10 is recommended [7]. The decisive factor here is a preliminary landscape analysis. After the selection of a potential target group and a mediation topic, the mediation goals must be worked out for the entire trail as well as for each individual station. Each station does not necessarily have to include all categories of educational objectives. A distinction is made between:

Figure 10.

Ideal/typical sequence of the concept of a geotrail [73].

- Learning objectives (cognitive objectives) (“what should the visitor have learned after walking the trail?”—e.g., “springs are fascinating habitats worth protecting”),

- Behavioural objectives (“what behaviour should the visitor be taught?”—e.g., understanding and, ideally, commitment to protecting and preserving spring habitats).

- Emotional goals (“what should the visitor feel?”—e.g., perceive spring habitats as beautiful; enjoy being in nature).

The techniques are selected according to the chosen objectives and the available human and financial resources.

In order for the trail to meet expectations, an evaluation should be carried out before and after the installation. Before the actual implementation in the field individuals from the selected target groups examine texts and, if necessary, installations for comprehensibility, functionality and degree of goal achievement. This step may be time-consuming, but it is particularly important if the concept creator does not belong to the intended target group. For example, research by Veverka [72] showed that all installations and texts of an exhibition for children had to be revised after a pre-evaluation because they did not meet the needs of the target group.

The evaluation during operation serves not only to clarify the degree of goal achievement, but also to optimize the trail. It should therefore be repeated at regular intervals.

2.4.3. Quality Criteria for Geotrails

A comprehensive elaboration of quality criteria for geotrails can be found in Section 5.2. Briefly summarised, a distinction must be made between infrastructural and content-related aspects in the realisation of geotrails.

Infrastructural aspects include the following points:

- Provision of information in advance (e.g., via a website)

- Hassle-free journey through appropriate signposting as well as connection to public transport or sufficient parking spaces in the immediate vicinity

- Optimal routing, both in terms of the design of the paths and clear signposting, in other words, a person who is not familiar with the area will be able to find his way without any problems based on the information/signposting [74]. In general, natural, narrow and winding paths are preferred. However, this depends on the target group. For families with small children (strollers) and people with mobility impairments, other paths or small detour routes are necessary.

- Complementary tourist facilities and activities (rest and seating facilities, gastronomy, …)

Content aspects include the following points:

- Consideration of the criteria of the heritage interpretation (see Section 2.3.1)

- Individual conception, no copies or standard elements, not even for activity stations.

- Clear target group definition, with texts and installations adapted to this; if necessary, new media

- Design of panels with interest-generating headlines, relatively limited text (note: Studies in Portugal showed that more than half of the visitors stayed for a maximum of one minute in front of a board the amount of text of which would have required four minutes to read. Only 3.4% actually stayed in front of the board for four minutes. Some individuals photographed the board without reading the text [75]) (if necessary divided into several information levels) (Figure 11), good visual material, if necessary graphics (for more information, see [16,53])

Figure 11. Well-designed panel with little text, different text levels and descriptive graphics. Volcano Trail Hohentwiel (Germany) (Megerle 2007).

Figure 11. Well-designed panel with little text, different text levels and descriptive graphics. Volcano Trail Hohentwiel (Germany) (Megerle 2007). - Concrete regional reference including cross-references to flora, fauna, humans and the environment; if necessary, panels can also be exchanged seasonally in order to address different aspects and at the same time arouse interest [14]. For this purpose, choose optimal location areas where the respective phenomena can be easily seen

- Involvement of the visitors; interactivity, addressing different senses, not only purely receptive texts

Empirical studies [70,76] and many years of personal experience show that visitors in Central Europe (we refer here to Germany and neighbouring countries) are not only willing to walk longer distances and read longer texts (as long as they are well formulated and attractively designed), but are also sometimes disappointed or underwhelmed when criteria for a primarily USA. audience are applied in an uninformed manner. Thus, for Central Europe, the path length of 800 m and maximum text length of 60 words recommended by Ham [43] seems clearly too low. It has been shown that text of up to 200 words were not a problem [76]. Additionally, a path aimed at adults should not be broken down to the reading and comprehending age of 13 years or less, as recommended by Hose [14]. In general, research results from German- and French-speaking countries seem to find only a limited entry into the English-speaking scientific community. Hose, for example, criticizes the insufficient research situation, but cites only English-language publications [14]. The extensive work from French- and German-speaking countries [7,16,38,77,78] is not taken into account. Here, a more intensive scientific exchange would be desirable.

3. Study Area

The Swabian Alb is a low mountain range in Southwest Germany, which stretches over a length of 220 km from the Upper Rhine in the Southwest to the border of the Nördlinger Ries in the North-east and thus covers an area of approximately 5800 km². The Swabian Alb is part of the Southwest German cuesta landscape. Lower (Lias) and middle (Dogger) Jurassic sediments shape the foothills, while Upper Jurassic sediments (Malm) form the striking cuesta, rising up to 400 m in height over the surrounding landscape. The flat Southeast facing plateau of the Jura, due to the prevailing limestone, represents the largest karst region in Central Europe and is characterized by diverse karst forms like caves, tufa cascades, and sinkholes. With 2400 recorded caves, including 12 show caves attracting annually over 320,000 visitors, there is no region in Germany with a higher number and concentration of caves. There are also numerous sinkholes, hunger wells, dry valleys, etc. [79]. A special feature are the forms of tertiary volcanism, which are concentrated in the Urach-Kirchheim area, and form one of the largest volcanic vent fields on Earth [50].

Southwest Germany is of global importance for geologists, boasting two meteor craters (Nördlinger Ries and Steinheimer Becken) and world-famous fossil sites (e.g., Holzmaden). It is also well known for Friedrich-August von Quenstedt’s research of Jurassic stratigraphy and Albrecht Penck’s exploration of the Ice Ages, for being home to the archaeological sites where Homo heidelbergensis and H. steinheimensis have been found and for the UNESCO World Heritage Site ‘Caves and Ice Age Art in the Swabian Jura’. (For further information on the geology of the Swabian Alb, see [79]).

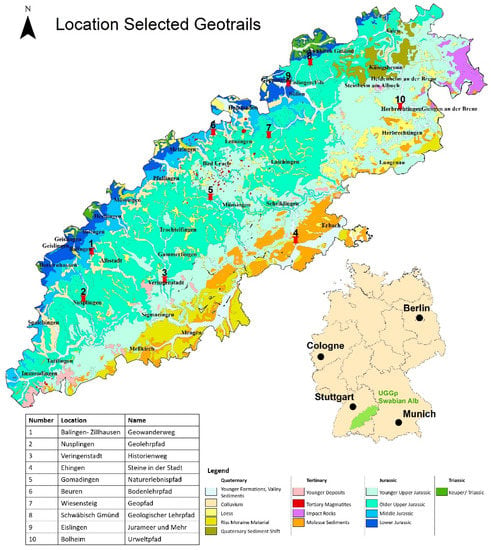

The Swabian Alb Geopark was established in 2000. In 2002, it was granted the status as a National and European Geopark; in 2015 as UNESCO Global Geopark. The Geopark encompasses virtually the entire Swabian Alb (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

UGGp Swabian Alb Geopark and geotrails selected for the study (Julian Stolz 2022).

4. Methodology

Our article draws upon extensive published national and international research on geotourism, geoparks, geoeducation and geotrails, particularly within our study region. Due to the focus on geotrails, literature on different trail concepts was evaluated in detail.

In the summer 2021, we conducted a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) analysis of the UNESCO Global Geopark Swabian Alb at the Rottenburg University of Applied Forest Sciences [80]. We analysed the current strengths, as well as weaknesses of the geopark. Furthermore, the research group discussed opportunities and threats. In addition to literature research and fieldwork, we conducted numerous interviews with tourism stakeholders such as the Tourism Association Swabian Alb, the Tourism Department, and Geopark managers including the UNESCO Global Geopark Swabian Alb headquarters and GeoUnion Alfred Wegener Foundation. One chapter of this SWOT analysis was dedicated to geoeducation. Based on existing documents [81,82] a survey of the geotrails in the UGGp Swabian Alb was conducted. This proved to be a challenge, as there is no comprehensive compilation of all educational and experience trails in the Alb. Indeed, the homepage of the geopark [82], the geotourism map with accompanying booklet [81], and the new discovery map published in 2021 [83] do not guarantee completeness.

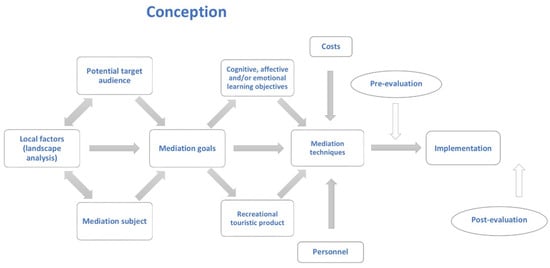

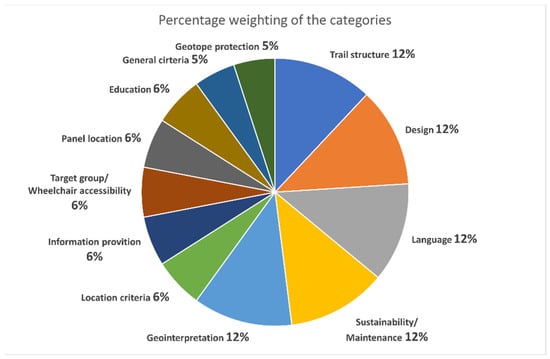

Selected geotrails were then examined in the field. Due to some results of the SWOT analysis, which showed clear weaknesses, a small research project was started. Within this framework, a list of criteria for good geotrails was first developed based on literature [14,15,16,45,55,57,84,85] and own experience (see Table 1). The individual criteria were weighted in relation to their overall importance (see Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Weighting of the individual criteria based on their importance.

Table 1.

Criteria for geotrail evaluation in UGGp Swabian Alb.

Figure 18.

Path not cleared. Use is thus no longer possible (Eistobel, Germany) (Megerle 2012).

Figure 17.

Path of Senses (Reutlingen, Germany). Text also in Braille (Megerle 2002).

Figure 16.

Representation of geological time spans in Dinoplagne (France) (Megerle 2022).

Figure 15.

Wooden board in the Bavarian Forest National Park (Germany) with writing difficult to read (Megerle 2000).

Figure 14.

Two signposts for pedestrians and for baby carriages (Megerle 2001).

Table 1.

Criteria for geotrail evaluation in UGGp Swabian Alb.

| Category | Criteria | Indicators | Notes | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concept and technologies | Individual concept | Individual tools | Specific, in-house concept, design and stations | Specific concepts are an essential quality feature and are mandatory for a well-founded interpretation and a touristic unique selling proposition |

| Individual design | ||||

| Individual stations | ||||

| New technologies | Use of QR codes | QR codes as a way of conveying information at different levels or in foreign languages | New technologies offer a wide range of possibilities for an expanded target group approach. The decisive factor is the problem-free functioning of the technologies | |

| Other new technologies | e.g., Apps, integration of smartphone functions, etc. | |||

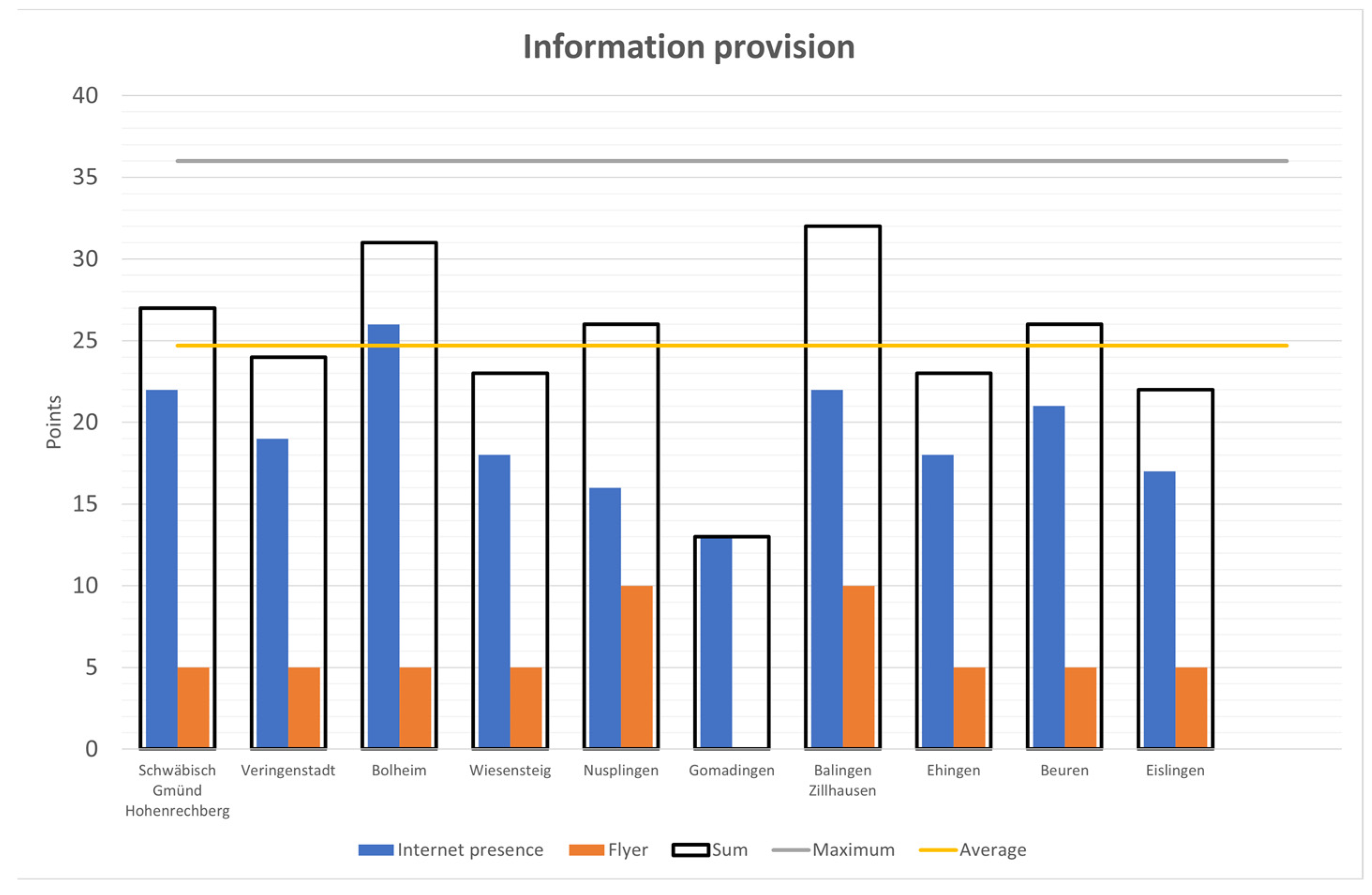

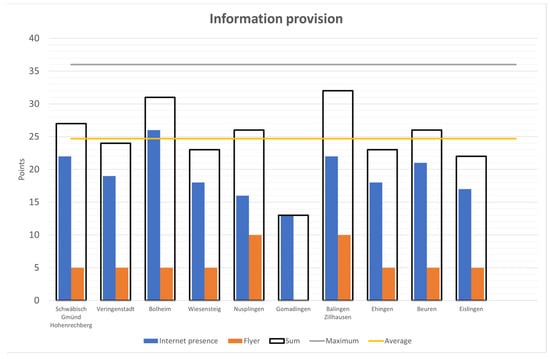

| Information provision | Internet presence | Relevant information about the trail | Starting point, length, target group; content, infrastructure | Can visitors obtain full information in advance? |

| Homepage is visually appealing and arouses interest | A user-friendly homepage animates and stimulates interest | Is information easy to obtain; is interest aroused? | ||

| Information correct | Checking the correctness in the field | See Section 6: Complete path does not exist in reality | ||

| Flyer | Flyer downloadable in advance | Support for the preparation of the visit | e.g., directions to the site | |

| Available on site | Support for walking the trail | Reminder; take with you for follow up | ||

| Location | Beautiful surroundings | Aesthetic landscape | Promotes interest in visiting | Objectification through criteria from literature on landscape aesthetics |

| Surroundings well-maintained | Littered surroundings do not encourage visitors to visit | The main point of criticism from visitors at the Urach waterfall was the littering | ||

| Accessibility | Parking facilities | Parking facilities with no time limit in short distance | Arrival mainly by own car | |

| Public transport | Public transport stop a short distance away | Promoting public transport in the context of sustainability | ||

| Approach well marked with signposts | Clearly recognisable and unambiguous | Searching for the path is irritating. | ||

| Reference to time and place | Influence of the phenomenon on the environment as well as the environment on the phenomenon is conveyed | Essential criterion of landscape interpretation (s. ch. 2.3.1). | “The calcareous and perforated soil can cannot store rainwater well, which is why the soil is dry and nutrient-poor. As such, the meadows in the area could mostly only be cultivated as juniper heaths”. | |

| Local peculiarities are conveyed | Unique selling proposition, regional awareness | “Due to the volcanic ash present, the conditions for growing grapes are optimal. That is why there are so many wineries in the municipality.” | ||

| Temporal dimension is conveyed | Geological time spans are sometimes difficult for laypeople to understand | “If you imagine the life span of the Earth as one hour on the clock, we humans have only been extant for one second, whereas this stone has already existed for half an hour.” | ||

| The phenomenon can be experienced directly | Geotope directly on the path | Direct reference to the phenomenon is an essential criterion of landscape interpretation | Figure. 5 Information about the Bilstein Geotope (Vogelsberg National Geopark, Germany) directly on site. | |

| Safe environment | Crossing roads/rails | A trail should not cross any transport infrastructure if possible | The safety of visitors, especially children, is a fundamental aspect. In case of an emergency, the scene of the accident must be quickly accessible for the emergency services. | |

| Dangerous topography | Slopes, ravines, erosion hazard | |||

| Rescue points available | Mobile phone reception secured | |||

| Escape routes available | Accessibility for rescue vehicles | |||

| Tourist infrastructure | Other sights in the vicinity | Possibilities to extend the visit and combine it with other things | Increasing regional value creation | |

| Gastronomy in the vicinity | Important tourism aspects | |||

| Path structure | Entrance area | Entrance panel with relevant information available | Comparable to the internet presence, but crucial for spontaneous visits | Can visitors fully inform themselves before the start of the walk-through? |

| Recreational infrastructure available | Benches, etc. | Especially important for seniors | ||

| Other infrastructure in the vicinity | Information centre, museum, gastronomy | Combination of several tourist facilities and activities | ||

| Easy to find | Entrance area already visible or easy to find from the car park | Searching for the entrance area is demotivating | ||

| Path | Path design | Narrow, curved paths are preferable to asphalted forest paths | Wayfinding arouses interest, creates tension. | |

| Adequate length | In relation to the respective target group | Paths that are too short disappoint; paths that are too long demotivate | ||

| Rest and refreshment facilities on the trail | Possibilities for a break, picnic on the way | Particularly relevant for families with children and senior citizens | ||

| Circular route | Circular routes are to be preferred to long-distance routes. | Public transport or car park can be reached without any problems. | ||

| Output range | End of the path clearly recognisable | End clearly recognisable, e.g., by appropriate sign, numbering of stations, etc. | Clear information for the visitor | |

| Final panel | Unambiguity; possibility to clearly summarise what has been conveyed | Take home message | ||

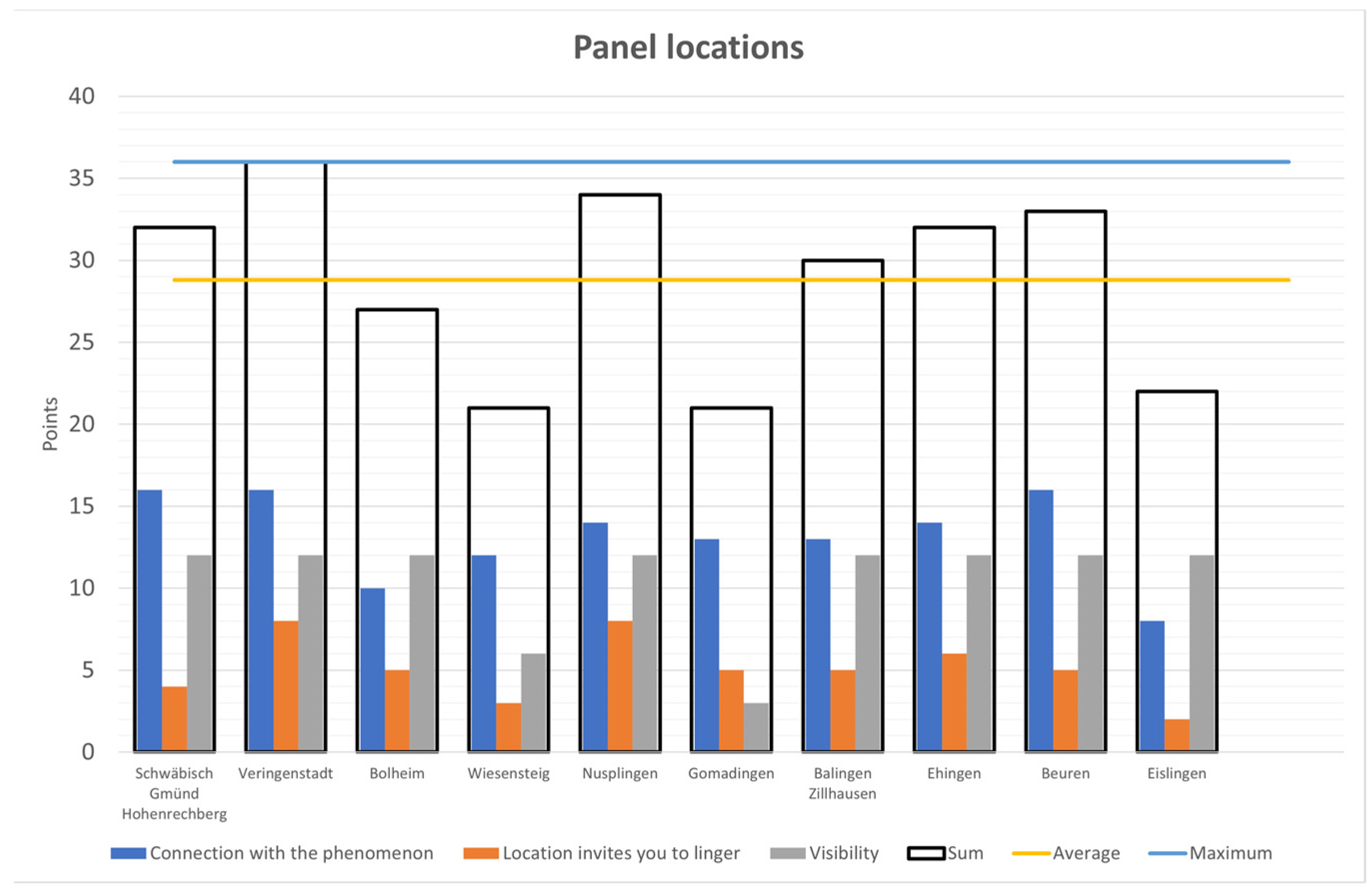

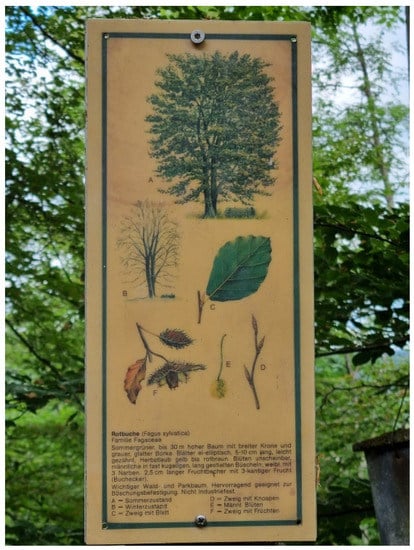

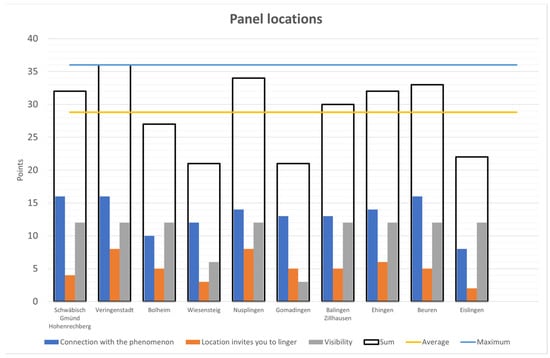

| Panel location | Connection with phenomenon | Phenomenon in visual relation to the panel | Smaller geotope in immediate vicinity; for landscape: relevant section visible | Essential criterion of landscape interpretation: concrete reference to concrete phenomenon (Figure 5) |

| Phenomenon recognisable | Even a lay audience can recognise the relevant phenomenon without problems. | Figure 4: The volcanic vent is not recognizable for a lay audience. | ||

| Location invites you to linger | Seating available; good standing position | A certain amount of time is needed for reading or for interactive elements. Is the location chosen in such a way that this is possible without, for example, obstructing other visitors? | Narrow paths or uneven terrain may not allow you to stay longer at a station. | |

| Aesthetic environment | Staying in a pleasant environment is preferred | See criterion “aesthetic landscape” at the beginning. | ||

| Visibility | Panel is visible and legible | Panel can be read without having to leave the path or decisively change the body posture | This also includes regular maintenance so that Information panels are not covered by vegetation, etc. | |

| Design | UGGp recognisable Corporate design | Recurring motifs/logos | Consistent use of recurring motifs/logos | A consistent graphic design creates a high recognition value; Logo can be used as an identification figure for children (see Figure 14). |

| Recurring colours and shapes | Consistent use to achieve a uniform impression | |||

| Structure of the signs/stations similar | Consistent structure and layout | |||

| Stations can be clearly assigned to the path | An important criterion specially in regions with different paths | |||

| Connection with Geopark recognisable | Logo of the Geopark present on the information panels | Increase awareness and identification with the Geopark | See Figure 5 with Logo of the Geopark. | |

| Colours and design inspired by the Geopark | Path design approximates the design of the Geopark. | Increase identification with the Geopark (see Figure 5) | ||

| Good graphical presentation | Colours harmonious | Consideration of colour theory; complementary colours are perceived as coherent. Colours harmonise with the surroundings without visually “disappearing”. | See Figure 11. | |

| Fonts coherent | Well-readable fonts that harmonise with each other and with the overall layout of the panel. | Ornate fonts are difficult to read, as are texts with only upper or lower case letters. The background also influences legibility (see Figure 15) | ||

| Good photos available | A picture is worth a thousand words, but only if appropriate and easily recognisable; too many pictures can be counterproductive. | Rocks etc. must be recognisable in detail on pictures so that even laypersons can recognise the necessary aspects, e.g., sedimentary structures, or mineral composition. | ||

| Good charts/graphics are available | Certain facts can be explained very well with graphics. These must be quick and easy to understand for laypersons. | Geological time spans can be well represented in graphs (see Figure 16) | ||

| Text readable from 2 m distance | Images and fonts chosen so that people with normal eyesight can easily read them. | Fonts or pictures that are too small have a demotivating effect. | ||

| Information | Amount of information suitable | Analogous to the target group, neither too much nor too little information | It is better to have several small information panels than one large overloaded panel. If necessary, additional information via QR code. | |

| Good balance between text and image | Texts and images complement each other more or less equally | In this way, information panels cater to different target groups. Reading readiness increases | ||

| Amount of information decreasing towards the end | Important information towards the front; attention wanes towards the end | |||

| Information scientifically correct | Information conveyed is simplified for lay people, but correct | This should be self-evident, but unfortunately it is not always the case, especially when a geotrail has been designed by people from outside the field. | ||

| Route guidance system | Consistent signage | Signposts easily recognisable and in uniform design | ||

| Not too many signs | A multitude of different signposts can confuse visitors | Quite common in tourist areas in Germany, as each hiking trail and path has its own signage. | ||

| Education | Activities arouse interest | Intrinsic motivation is awakened | It is crucial to arouse the interest of casual visitors in particular. | This can be done through unusual headlines, design, images, etc. |

| Direct experience | Different senses are addressed | The station offers not only purely receptive texts, but also appeals to several senses (e.g., hearing, touch, etc.). | In contrast to traditional nature trails, nature experience trails always work by appealing to different senses. | |

| Visitors are actively involved | Not just purely receptive texts, but invitations or installations to become active themselves. | Things are easily remembered when you actively take part. | ||

| Stimulates the visitors | Cognitive stimuli present | Visitors are mentally stimulated, e.g., suggestions to think about certain things | More intensive engagement with the subject matter | |

| Motor stimuli present | e.g., addressing the sense of balance; climbing, … | More intensive engagement e.g., with a particular geological formation | ||

| Integration of Education for Sustainable Development | At least one Sustainable Development Goal is addressed | ESD is one of the core tasks of the UGGp | ESD should enable people to think and act in a way that is fit for the future | |

| Aspects of sustainability and environmental protection are taught | UGGps are to be model regions for sustainable development. | Sustainability and environmental protection as a contribution to future viability | ||

| Visitors are encouraged to think for themselves | Pathway encourages people to look at specific issues, e.g., climate change and glacier melt. | Visitors should continue to engage with the respective topic even after their visit to the trail | ||

| Language | Good wording of the texts | Scientific-technical terms reduced in a way that is understandable for laypersons | Succeeds in presenting complex geoscientific aspects in a generally understandable way. Technical terms are explained | Extensive and incomprehensible technical vocabulary can repel visitors |

| Simple, understandable language | Box sentences and complicated formulations make it difficult to read and absorb the texts. | “The limestone layers in the lower part consist of approx. 4 m thick rock beds (oolites) with ooids up to 5 mm in size in the base sections, in which coarse and fine oolitic beds alternate” (Panel Geopark Harz). | ||

| Language at “eye level“ | Superior teacher-like formulations are usually met with rejection | “Keep this in mind!” “As you already know” | ||

| Geo-interpretation | Reference to everyday life is established | Relation of the phenomenon to the everyday world of the visitor | Are visitors and the phenomenon connected? | “In the past they would have used the “Stubensandstein” (Löwenstein Formation) as a cleaning agent; hence the unusual name” |

| Comparison of the phenomenon with everyday life | Complex issues are explained through comparisons. | The Grand Canyon is like a massive pancake pie or the rock layering is like a lasagne | ||

| Deeper meaning of the phenomenon is conveyed | Some things are not directly perceptible. | Reykjavik is the cleanest capital in the world, as it is almost 100% supplied with district heating from geothermal power plants. This is thanks to the active volcanism in Iceland. | ||

| Storytelling | Stations of the trail are connected by a story | The individual stations are elements of a story | The Feldberg Pixie-trail tells the story of Anton the Capercaillie. | |

| History is exciting | Visitors are interested in following the story further. | The Search for Anton the Capercaillie is not only exciting for children. | ||

| Horizon is broadened | Visitors experience new situations | The trail puts visitors in new situations or opens up other perspectives | Stimulating to walk barefoot over a boulder field or feel volcanic warmth. | |

| Visitors take a new perspective | The familiar is perceived differently | A mirror makes it possible to see things in a new way. | ||

| Connectedness with phenomenon is conveyed | Beauty/uniqueness of the phenomenon is conveyed | Visitors are made aware of uniqueness that they would otherwise not have noticed | Fossilised ripple marks in the Haute Provence Geopark. | |

| The phenomenon’s worthiness of protection is conveyed | Visitors are explicitly made aware of the need for protection. | Geological phenomena are often perceived as “stable”, whereas e.g., calcareous tuff formations are highly vulnerable [86]. | ||

| Various linguistic stylistic devices are used | Metaphors, comparisons, examples, analogies | Are linguistic means used that are suitable for conveying knowledge and feelings? | “Does the rock have sunburn?” Panel on the Rotliegend Group in Schramberg. | |

| Connections are shown | Connections between geopotentials, flora, fauna and people are shown | Does the path regularly show these connections? | e.g., fertile soils, good exposure, viticulture, regional economic value creation | |

| Central theme present | Orientation through central theme | “People forget facts, they remember themes” [43] | The Hainich—a primeval forest in the middle of Germany | |

| Connects the stations by a central theme | Can all stations be assigned to the main guiding idea? | Path to the Danube seepage near Tuttlingen | ||

| Captivates the audience | Main idea is well and concisely formulated | Trees are the lungs of the earth | ||

| Target group | Targeting the right audience | Clear focus on a target group | Is a specific target group named and is the pathway also designed accordingly? | Anton the Capercaillie—explicitly for families with children |

| Communication on several levels | To what extent is communication done on several levels, if applicable? | Hohentwiel Volcano Trail with main text and additional information (see Figure 11) | ||

| Language appropriate to the target group | Language of the audience | Is the language appropriate for the target group? | DinoPlagne (see Figure 16) Texts for adults and for children | |

| Multilingualism | If information is communicated in several languages | DinoPlagne (see Figure 16) or via QR codes | ||

| Child-friendly design | Elements within reach for children | Can a primary school child operate the installations? | Stockach Spring Experience Trail (see Figure 8): Installations clearly too high. | |

| Information panels readable for children | Child-friendly texts and positioning | Integration of the term “Messages” on a German trail for families with children. Not understandable for children. | ||

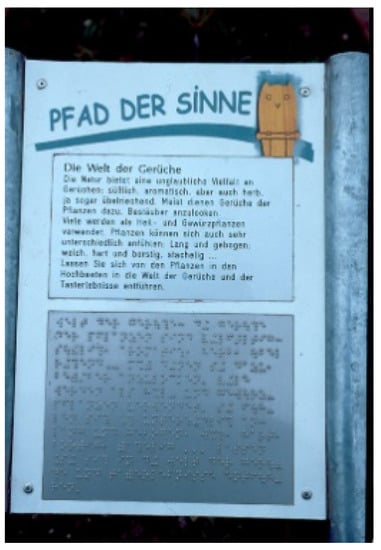

| Accessibility | Path accessible to all | The visually impaired and those with learning difficulties are also taken into account. | Path of the Senses in Reutlingen with Braille (see Figure 17) | |

| Path suitable for wheelchairs and prams | Have paths been chosen that are accessible to prams? | If necessary, two pathways (see Figure 14) | ||

| Geotope protection | Maintained geotopes | Geotopes are kept free of vegetation | This concerns both the geotope itself and the access route. | Some geotopes are no longer easily accessible or recognisable for visitors due to overgrowth. |

| No littering | This also includes how waste disposal is organised; are there rubbish bins; are there approaches such as “take the memories with you and also the rubbish”? | Hollow forms (sinkholes, etc.) in particular are sometimes filled with rubbish or excavated earth. | ||

| Geotopes are accessible | Can visitors easily get close enough to the geotope to see details | Mineral inclusions or fossils are sometimes only visible at close range | ||

| Geotopes are protected | Barriers are available if necessary | If barriers are necessary, near-natural materials (wood) are rated better than non-natural materials. | Barriers may be necessary, but can look very unsightly. | |

| Signs, if necessary prohibition signs available | Are the visitors informed about the reason for the barrier? | Explanations for barriers increase the understanding for such measures. | ||

| Sustainability/Maintenance | Care of the wards | Stations in good condition | Are all stations and information panels routinely maintained? | Broken stations and faded information panels are extremely counterproductive. |

| Information panels in good condition | ||||

| Stations protected from the weather | Was care taken in advance to protect or position the stations well? | Sun-exposed information panels fade more quickly. Leaves or snow may remain on sloping information panels. | ||

| Robust materials | Robust stations | Were materials used that last and are stable in the long term? | Robust materials are more sustainable in the long term as less replacement is required. Information panels still in good condition after twenty years. | |

| Robust information panels | ||||

| Robust signposts | ||||

| No vandalism | Is there any damage, graffiti or similar? | Signs of vandalism can be an indication of non-regular monitoring | ||

| Road safety | Paths not overgrown | The safety of visitors must be ensured; at the same time, branches on the paths, etc. are an indication of inadequate maintenance | See Figure 18. With such obstacles, a path can no longer be used. | |

| No logs/branches on the path | ||||

| Slopes secured; railings or bridge available if necessary | ||||

| Support from other actors | Support through an association | If associations or the community support and maintain the path, this speaks for a high level of identification. | The Barefoot Trail near Freudenstadt is walked daily by a pensioner to guarantee the safety of the path. | |

| Support from a municipality | ||||

| Sponsorships or similar | ||||

| Funding | Sponsoring | Does the path receive funding, not only for concept and construction, but also for ongoing maintenance? | The History Trail in Veringenstadt could only be financed thanks to funding from the Upper Danube Nature Park. | |

| Funding, e.g., EU programmes | ||||

| Donation box or similar | ||||

| Visitor feedback | Feedback box on site | Feedback from visitors is essential for path management and should therefore be easily accessible. | Unfortunately, examples of this are rare. Mostly, points of criticism tend to be posted on corresponding internet forums in general. | |

| Feedback options via homepage |

Based on the SWOT analysis, a total of ten geotrails were selected for detailed evaluation using this list of criteria (see Table 1 and Figure 13). For this purpose, a definition for geotrails had to be chosen as the first step (see Section 5.1), as it became apparent that not all paths listed as geotrails could truly be accepted as such. The selected ten geotrails were then mapped in the field and evaluated against the list of criteria. Our results from the UGGp Swabian Alb were then compared with the information from the (inter)national literature. Finally, recommendations for model geotrails were derived (Section 2.4.3). The term “model” refers in this case to aspects of geoeducation as well as geotourism.

In addition, this study is broadened by more than two decades of first hand personal experience as a scientist, landscape guide, and vice chairwoman of the advisory board of the UNESCO Geopark Swabian Alb.

5. Evaluation of Existing Pathways in the UGGp Swabian Alb.

The evaluation of existing trails included several work steps, which are described in more detail below.

5.1. Definition, Survey and Selection of the Investigated Geotrails

To address the research question, the first step was to develop our definition for Geotrails in order to be able to clearly assign trails to this category. First, the following definition was applied:

A geotrail in this paper requires a path length of at least three kilometres, at least five stations, at least 50% of the stations with a direct or indirect reference to geology.

Once this has been completed, an inventory of the geotrails within the area of the UGGp Swabian Alb has to be made. This proved to be a challenge in two respects. On the one hand, no reliable list of all trails exists. Trails are designed and maintained by a wide variety of stakeholders (municipalities, nature conservation centres, private individuals and companies). Some of these trails are intensively advertised, while others are known only as an inside tip. In addition, terrain surveys were mandatory, since paths did not always correspond to the description on the Internet or in printed works, and in some cases simply no longer existed.

In 2003 the geotourism map for the UGGp Swabian Alb was published by Huth & Junker [81]. This map, supplemented by a detailed booklet, lists geotourism destinations including museums, educational and experience trails, nature conservation centres, and selected geotopes. The booklet contains information on the location, accessibility, and geological features for each geotope listed. In 2003, 19 nature trails were listed for the entire UGGp. Whether the survey covered all existing trails at that time could not be verified almost 20 years later. Of the trails listed at that time, not all meet our definition of a geotrail. The point of criticism almost always is a number of geoscientific stations that is below 50%.

In 2021, the so-called discovery map was published [83]. The total of seventy areas to be discovered contains only four geotrails:

- The Nusplingen Geological Nature Trail

- The Zillhauser Waterfall Geological Hiking Trail

- The Veringenstadt History Trail

- The Schwäbisch Gmünd Geological Trail

However, only a selection of geotrails is deliberately presented in the discovery map. For example, the Mössinger Landslide, a national geotope, is listed, but without the local geotrail.

For the SWOT analysis [80], 33 nature trails were examined. Of these, 22 were listed on the homepage of the UGGp Swabian Alb; the other eleven were taken from Huth & Junker [81]. The results of the SWOT analysis showed some weaknesses. A subsequent detailed analysis of our research project revealed two critical points: First, the number of educational and adventure trails in the UGGp Swabian Alb is generally relatively low. The Geopark homepage lists only 22 trails. Second, some of these already limited trails address multiple and diverse topics. A strict application of our definition of a geotrail would have resulted in less than ten trails, which we consider as a minimum for an evaluation of the developed criteria.

Therefore, the following criteria were used for the selection of the trails: no minimum trail length, at least four stations, geological reference of the trail to be mentioned in the online content.

From all trails that met these criteria (25 in total), ten trails were selected for detailed analysis in the field. Attention was paid to a largely balanced geographic distribution within the Geopark setting and to the coverage of different geological topics. In addition, care was taken to integrate at least two trails that were specifically advertised for children. These trails were then walked in the company of children in order to check their actual suitability, to observe the children’s reactions, and to assess the stamina of the children for the distances involved.

The spatial distribution of the paths studied is shown in Figure 13 and described in more detail in Table 2.

Table 2.

Trails selected for detailed analysis in UGGp Swabian Alb.

5.2. List of Criteria for the Evaluation of Geotrails

As explained in Section 2.4.1, studies worldwide show that trails often do not meet the expectations placed on them. This was also shown by initial explorations in the UGGp Swabian Alb. In order to be able to carry out a well-founded evaluation of the existing geotrails, a corresponding list of criteria had to first be identified and defined. The elaboration of the list of criteria was based on those mentioned in the literature, the SWOT analysis of the UGGp [80], previous on-site investigations as well as personal experiences. The comprehensive list of criteria included infrastructural criteria (accessibility, length of the trail, trail conditions, etc.) as well as design aspects (media used, readability, colour selection, etc.) and educational aspects (comprehensibility of the information, reference to local phenomena, etc.). Furthermore, attention was paid to the presence of supplementary materials (brochures, digital media, etc.), target group orientation, geoconservation and the connection to the Geopark. For more details, see Table 1.

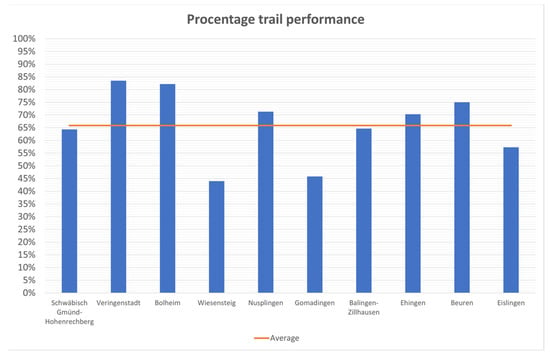

Each criterion was rated on a point scale from “fulfilled completely” to “not fulfilled at all”. For the overall assessment of the individual paths, the individual criteria were weighted as shown in Figure 13. Aspects that were considered to be more important for the optimal design of the paths (e.g., adequate texts) were weighted higher than, for example, the provision of information online or via flyers. However, the weighting can be changed quickly and with ease via Excel tables used if other aspects are considered more important in specific cases.

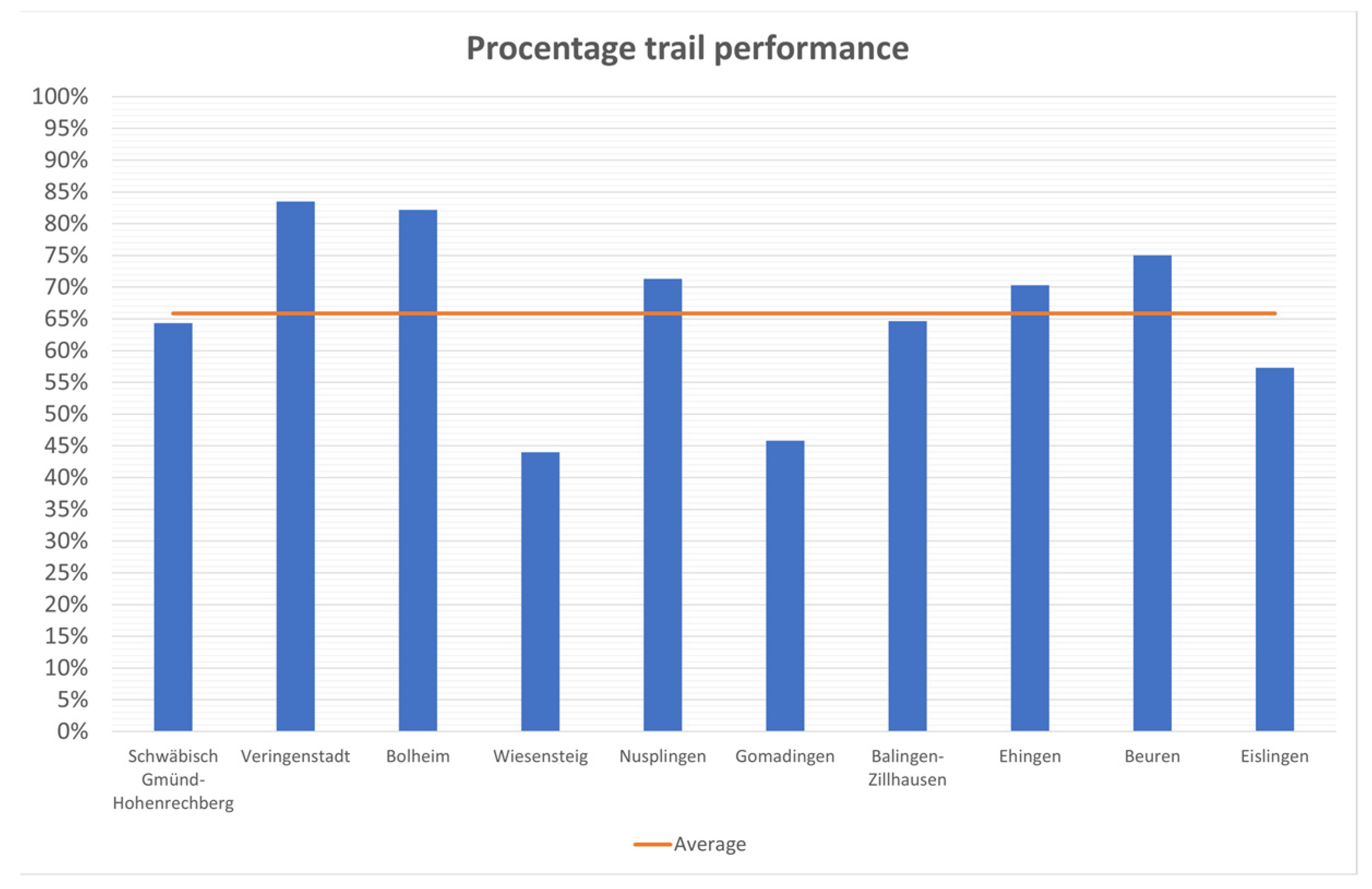

6. Results of the Evaluation of the Geotrails in the UGGp Swabian Alb

Earlier research showed that some trails failed to meet even relatively mundane expectations [16].