Abstract

As an environmental policy that directly brings economic benefits to farmers, ecological compensation should achieve the dual goals of ecological environmental protection and rural poverty reduction. With the implementation of various ecological compensation projects, a large number of studies began to focus on the impact of ecological compensation projects on rural labor transfer employment. However, most of the existing studies focus on a specific project and fail to consider a comparative analysis of different types of projects. Therefore, this study used the survey data of 1279 rural laborers in the Yanqing District of Beijing to analyze the impact of different types of ecological compensation projects on the transfer employment of rural labor from the perspective of self-development capacity. The results show that post-based ecological compensation projects provide a low quality of posts and weaken the initiative of participants to further expand their employment channels. Land-based projects downsize agricultural production and reduce the agricultural production activities of participants, without significantly increasing their likelihood of transfer employment. In the long run, the current implementation of ecological compensation projects may cause problems regarding labor surpluses and land restoration. This study has certain practical application value and practical guiding significance for further improving the design of ecological compensation mechanisms.

1. Introduction

The concept of ecological compensation in China is similar to the international concept, which involves a conditional transfer payment for ecological service providers who have lost development opportunities [1]. Most of China’s ecological compensation is conducted in the form of government projects [2,3]. At present, rural areas in China are the focus and represent weak areas of environmental governance. Due to the rich natural resources, these areas are key for implementing ecological compensation projects [4]. Existing projects implemented by the government are mainly designed to compensate for changes in land use patterns or behaviors in protecting the ecological environment. The transformation of agricultural land into ecological land or the establishment of ecological protection posts will have an impact on the employment of the local labor force. Therefore, the success of the rural ecological compensation projects depends not only on the ecological restoration effect of the projects, but also on the transformation of the rural economic structure characterized by the industrial transfer of rural labor. Some scholars believe that the fundamental solution to the “three rural issues”, i.e., agriculture, rural areas and rural people, is to promote the transfer employment of rural surplus labor to non-agricultural industries [5]. The proportion of employees in industries such as handicrafts and services in the total population of a certain village is proportional to the development of its economy and society [5,6]. If the implementation of ecological compensation projects can bring stable employment and income to participants, then the concern of the government regarding the damage of the livelihood behavior of farmers to the environment after the projects end will be eliminated [7].

Considering the externalities of farmland ecosystem ecological services and the weaknesses of agriculture itself, ecological compensation follows the principle of user payment, and is one of the mainstream policy tools in the field of international agro-ecological governance. In Europe and the United States, there has been a long history of agricultural ecological compensation. The main objective of agricultural ecological compensation in the United States is to prevent and control the damage to the ecological environment caused by agricultural production, and to compensate farmers for the economic losses caused by land conversion or the cost input borne by the implementation of environmentally friendly agricultural production modes on the land without conversion [8]. Specific projects include the conservation reserve program, wetland reserve program, farm and ranch land protection program, environmental quality incentive program, grassland reserve program and conservation security program, etc. [9,10]. The European Union’s agricultural ecological compensation policy mainly compensates for the positive environmental externalities of agricultural production, reduces the occurrence of negative externalities, and compensates farmers for changing the original production mode in order to meet the increasing requirements of environmental laws and regulations [11,12,13,14].

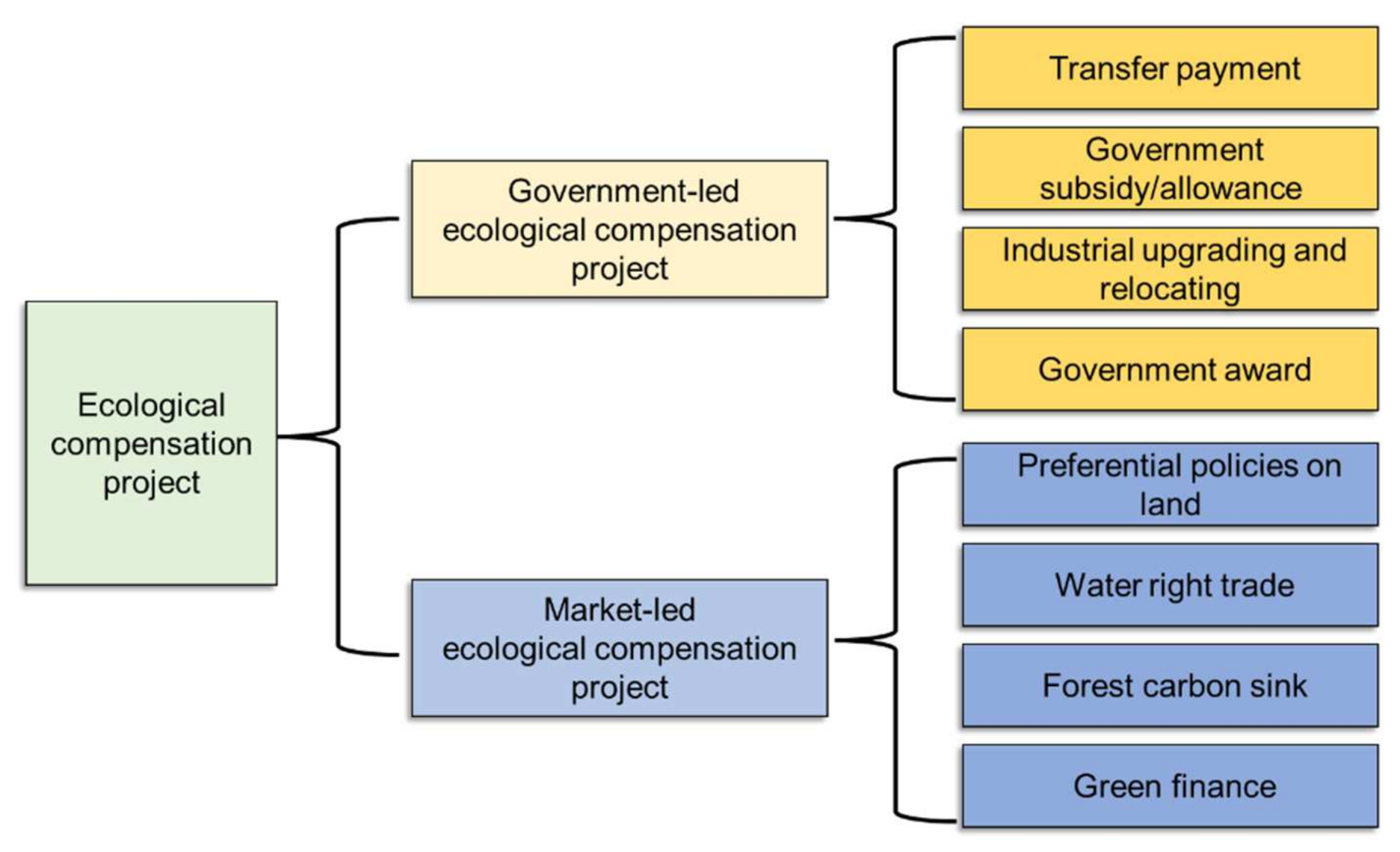

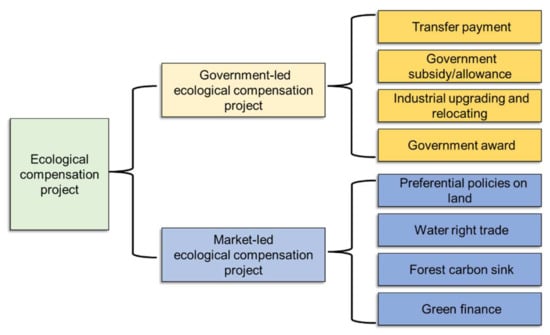

China’s ecological compensation project started relatively late. According to the buyers of ecological services, China’s ecological compensation can be divided into government-led and market-led types [15,16]. As shown in Figure 1, its concept in practical applications remains relatively vague, and it is even expressed as a “subsidy”, “reward” or “allowance” in some policy papers [16,17]. In addition, most of the areas where ecological compensation is implemented in China are relatively poor and backward. Local farmers have been living in these areas for generations and have formed relatively mature social networks and communication methods. Compared with migrant workers, they are obviously more inclined to work locally [16,17]. In China, farmers only have the contracted right to operate the land, and the village committee is the owner of the land. After the government formulates the legal distribution scheme, the land compensation fee will be distributed to the farmers through the village committee according to the scheme [16,18]. However, since the local officials fail to fully understand the actual purposes of ecological compensation when implementing ecological compensation projects, some ecological compensation projects have not achieved good results in solving the problem of farmers’ employment and income increase [19,20,21,22,23]. The survey of Guizhou and Ningxia provinces by Uchida reveals that local farmers may re-cultivate the restored land and adopt previously used agricultural production methods if they cannot find non-agricultural work opportunities before the project compensation ends [20]. According to the tracking data of Shaanxi, Gansu, and Sichuan provinces, Yi found that the conversion of farmland to forest projects had no significant promotional effect on the transfer employment of the rural surplus labor force [21]. In addition, some studies have shown that ecological compensation projects have a good promotional effect on the transfer employment of the rural labor force in some areas [24,25], e.g., Yang proved that the impact of ecological compensation projects on the per capita income of households significantly increased during the 10 years of implementation, based on a field survey in the Luanping and Fengning counties, Hebei province [25].

Figure 1.

China’s ecological compensation project.

Through the above analysis, it can be found that the different implementation modes of ecological compensation projects may have different impacts on the transfer employment of rural labor. However, most of the existing studies focus on a specific project in a certain region, while neglecting a comparative analysis of different types of project implementation modes. Therefore, in order to fill this research gap, this study uses the survey data of 1279 rural laborers in the Yanqing District of Beijing to analyze the impact of different types of ecological compensation projects on the transfer employment of rural labor from the perspective of self-development capacity, by incorporating various project implementation modes into one system.

2. Theoretical Analysis from the Perspective of Self-Development Capability

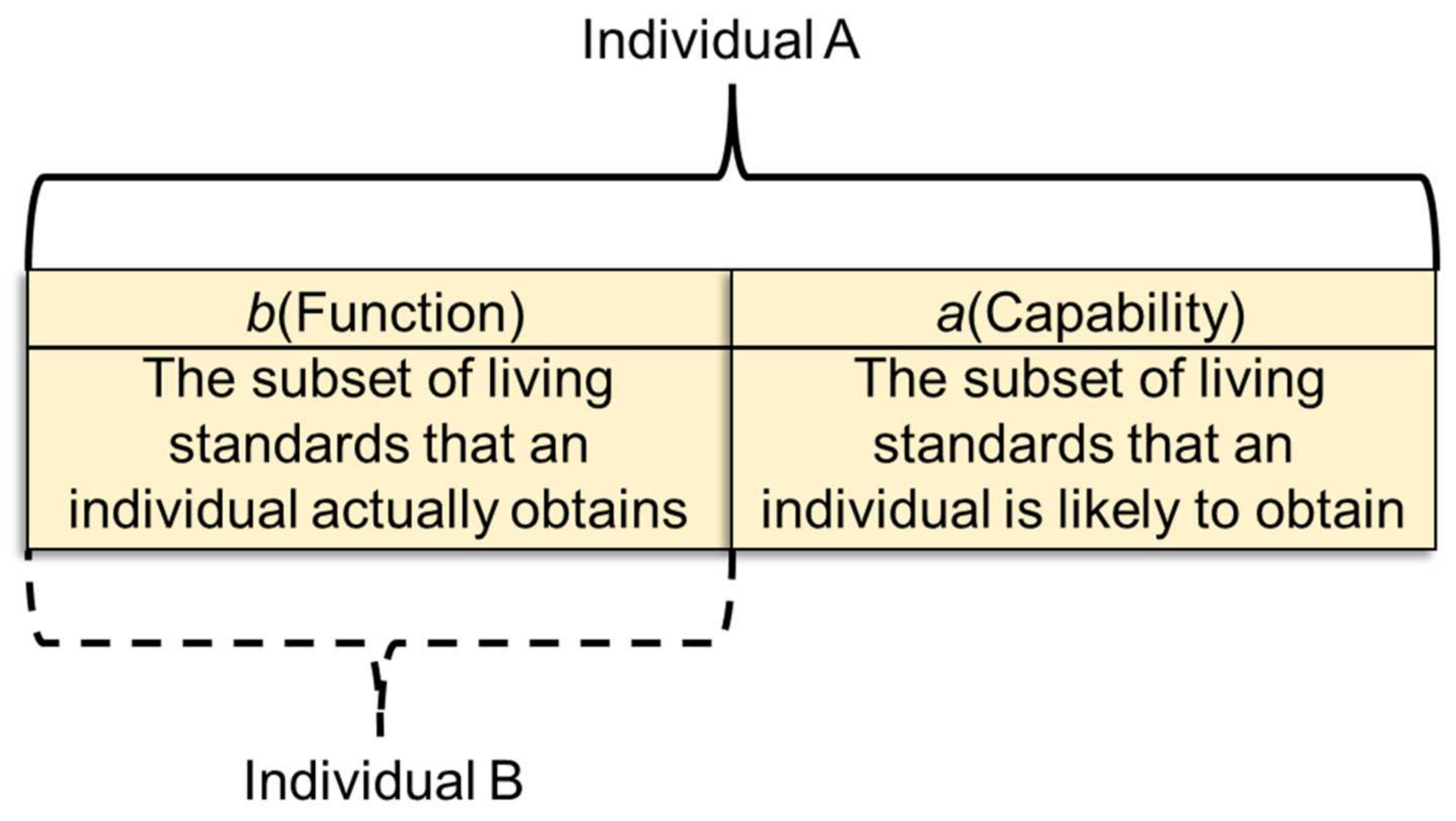

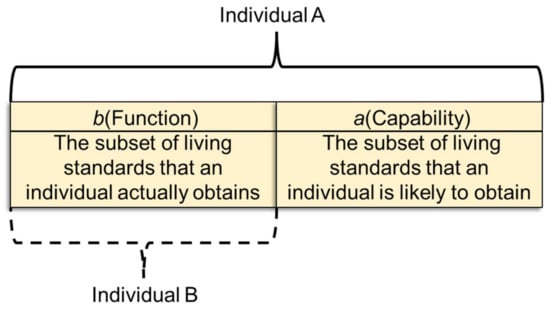

Self-development ability emphasizes the internal foundation and hematopoietic function of the system, and does not exclude the support and promotion of external forces. It emphasizes the need to make good use of the support of external forces according to their own conditions. When this concept is applied to the research of ecological compensation, it serves to improve the theory of ecological compensation from the perspective of farmers, which will help all industries to better understand the functional orientation of ecological compensation in the ecological environment protection of rural areas, as well as in the development of the economy and society, thus contributing to the more effective functioning of ecological compensation in practice. The theoretical source of self-development capability is Amartya Sen’s capability approach theory, with the core view that the welfare level or living standards of an individual are not affected by the object itself, but by the individual’s capability to use it, and the same type of resource can be transformed by different individuals into different functional activities in different environments [26]. Two basic concepts of “function” and “capability” are mainly involved in this theory [27]. Specifically, “function” is what an individual actually does, while “capability” is what an individual has substantial freedom to do. As shown in Figure 2, a complete set (b, a) is assumed, where b is the subset of living standards that an individual actually obtains, i.e., the subset of function activities, while a is the subset of living standards that an individual is likely to obtain, i.e., the subset of capability activities. If the selection set of individual A and individual B is the complete set (b, a) and the subset (b), respectively, then their welfare is different even if both eventually choose the subset (b). Individual A, with additional choices, has higher welfare than individual B, with no more choice. Therefore, the selection under only one choice is different from that under additional choices [28].

Figure 2.

Two basic concepts of “function” and “capability”.

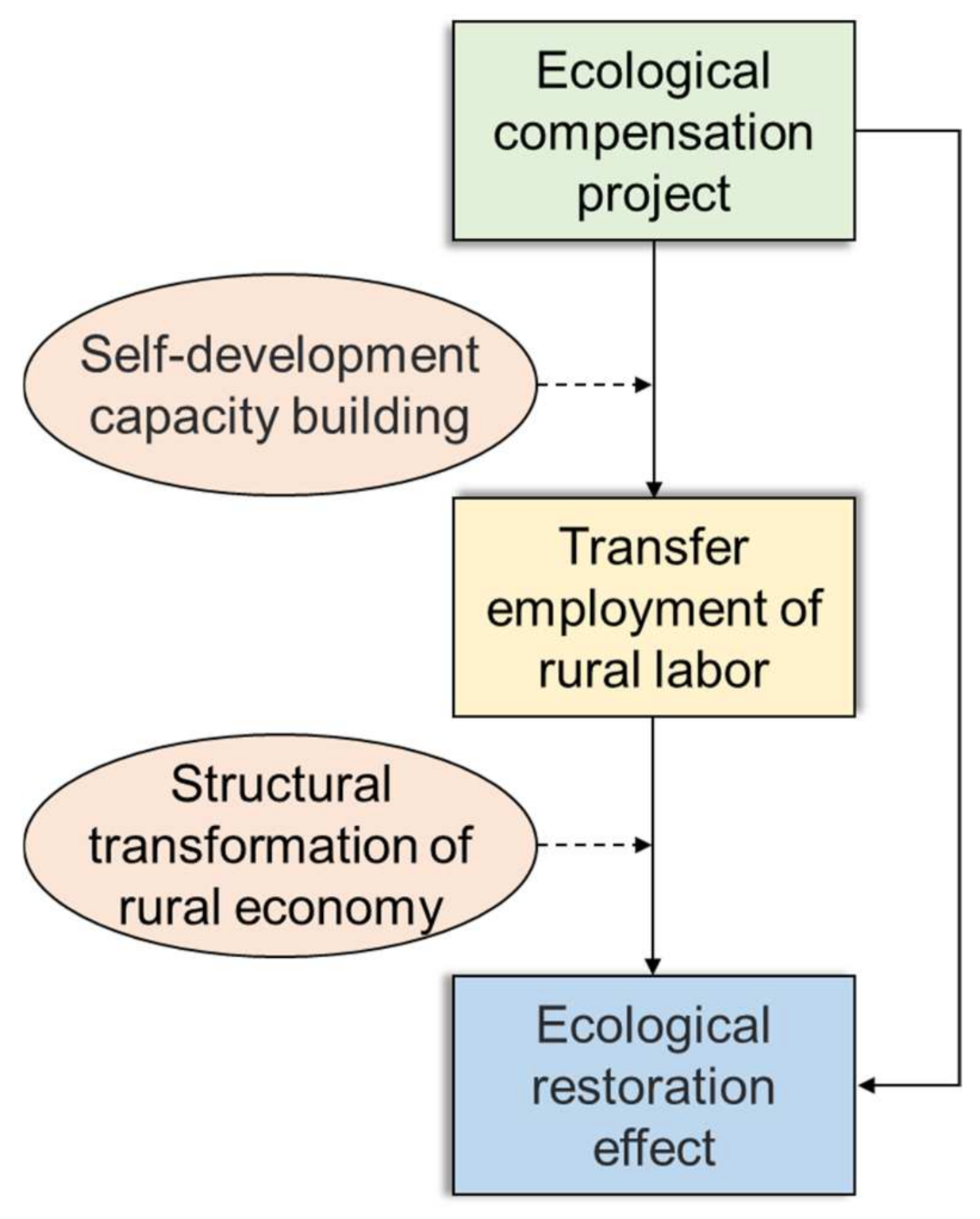

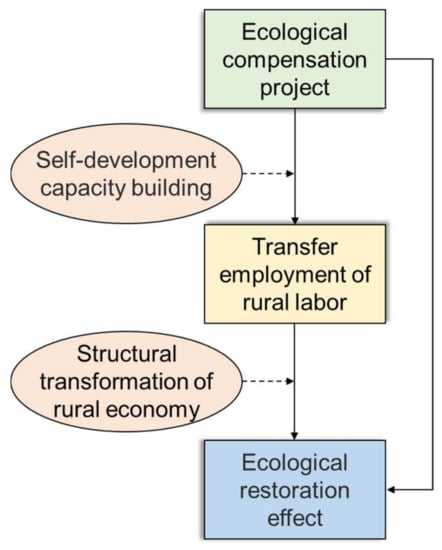

The majority of the research on the capability approach theory takes vulnerable groups as the research object. In general, the providers of ecological services are poor people in relatively backward rural areas [29]. Due to limitations of cognitive scope and knowledge, the economic exchange ability, political negotiation ability and cultural inspiration ability of these ecological service providers are very limited. The capacity space of the individual is very small, and it is difficult to obtain more resources with their own ability. They are often in a disadvantageous position in the pattern of interests. Many examples can be found in the aspects of the main business, sideline business and the social security that farmers participate in. In reality, ecological protection and economic benefits are often asymmetric. The research from the perspective of capability pays more attention to enhancing the capability activities of participants in ecological compensation projects [30]. These ecological service providers need to produce ecological services on the one hand and build their own capacity on the other. The former is focused on the improvement of human capital, while the latter is focused on the improvement of self-development capability. During the implementation of ecological compensation projects, livelihood training for participating farmers is necessary, in order to improve their capabilities to eliminate of the single mode of land production [31]. The construction of self-development capability in rural areas under the support of ecological compensation as an external auxiliary force can promote the transfer employment of the rural labor force and boost the structural transformation of the rural economy, thereby alleviating the pressure of the rural population and agricultural production on the ecological environment, which is the desired long-term effect of ecological compensation projects. This logical relationship is visualized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Study on ecological compensation based on a self-development capability perspective.

3. Methodology

3.1. Case Study Area

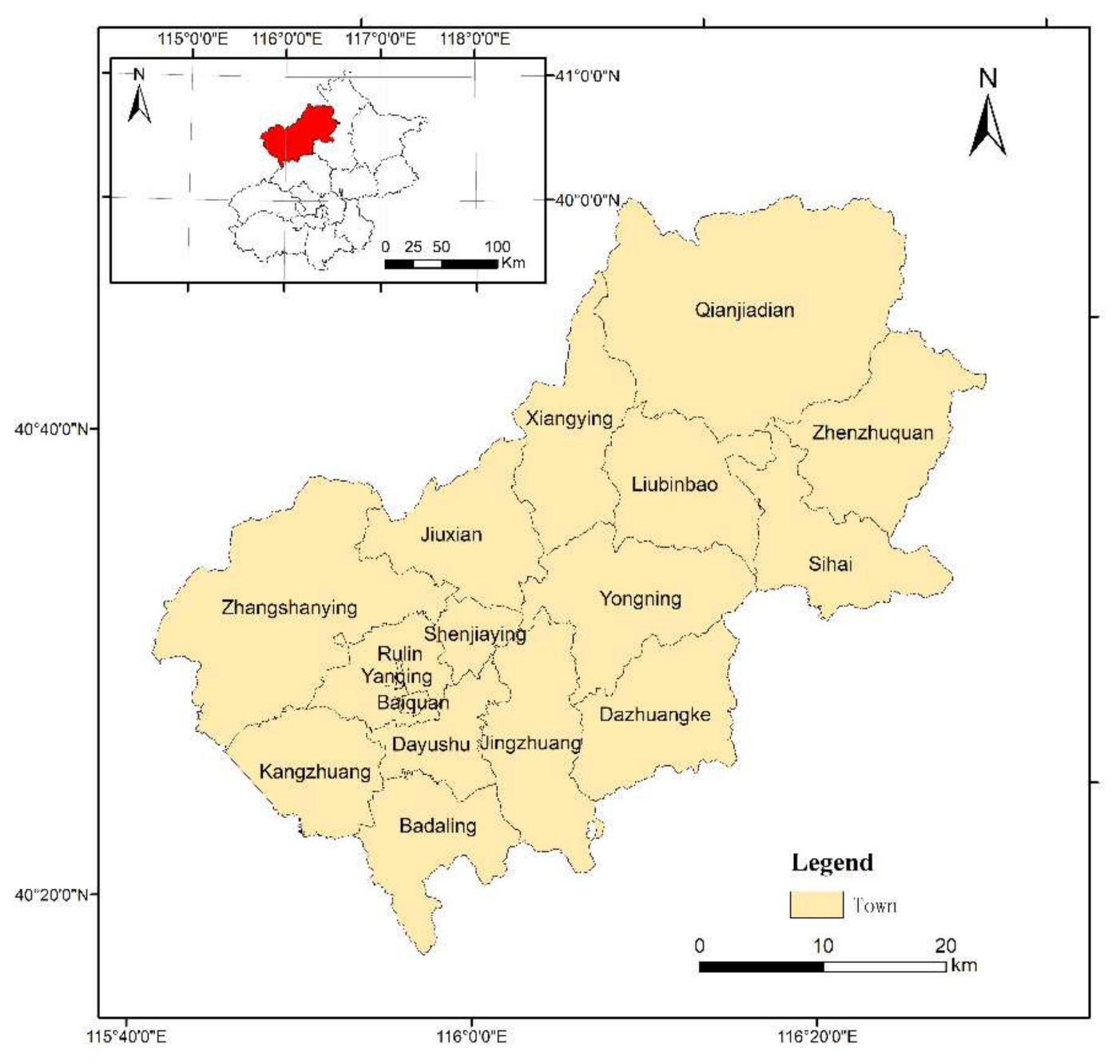

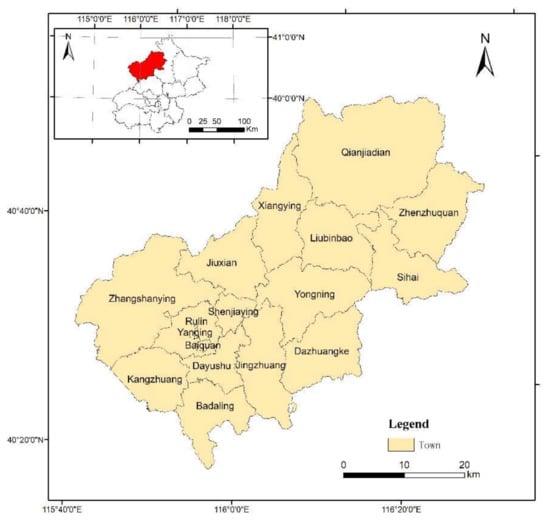

The Yanqing District, located in the northwest of Beijing, is an important water source and ecological shelter of Beijing and one of the five ecological conservation areas set by Beijing. In the national planning of major function areas, the Yanqing District is located in the Northern Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei water conservation functional area, which is one of the 63 important ecological functional areas in China. Covering 15 rural towns, 3 subdistricts, 376 administrative villages, and 33 communities (Figure 4), the Yanqing District is rich in forest resources, with a forest coverage percentage of 74.5%. Mountains and hills represent nearly 15 million square kilometers, accounting for 72.8% of the total land area. Under the functional orientation of an ecological service provider, the industrial distribution, employment area and income of rural labor in Yanqing show distinct characteristics. The industrial distribution displays such a pattern where the tertiary industry is in the first place, followed by the primary and then the secondary industry. The amount of the labor force clustered in the primary industry is still relatively large, while the labor force absorbed by the secondary industry is insufficient. In 2016, the average number of employees in industrial enterprises above the designated size in the Yanqing District accounted for 0.84% of that in Beijing, and the average number of employees in tertiary industry above the designated size accounted for 0.67% of that in Beijing. Compared with the average of the whole of Beijing, the number of employees in the secondary and tertiary industries was very small. Local employment was the primary form of employment, with more than 60% of the rural labor force working in rural towns. The Yanqing District is one of the outer suburbs, with a low level of development in Beijing. The total employment income of farmers’ households is dominated by non-agricultural income. In 2016, the non-agricultural income amounted to 13,000 yuan, 6.5 times that of the agricultural income (2000 yuan).

Figure 4.

Case study area. The red plate is the location of Yanqing in Beijing.

The ecological compensation projects that directly subsidize farmers are categorized as post-based and land-based in this study. Post-based projects refer to the setting of ecological protection posts by the government in rural areas with plentiful natural resources, the essence of which is a public service purchase on behalf of the public by the government. Land-based projects seek to change the land contract rights or the original terms in the contract to transform the agricultural land into ecological land, under the condition that the land ownership or management rights remain unchanged. According to the implementation of various ecological compensation projects in Yanqing, the post-based projects of ecological compensation studied in this paper include eco-forest ranger, eco-cleaner and eco-water tender projects, and the land-based ecological compensation projects include plain afforestation and grain-for-green projects. The participants of post-based ecological compensation projects, who take up responsibilities such as forest and water protection, receive monthly subsides of approximately 500 yuan per person. In 2016, a total of 129 million yuan was invested in ecological protection posts, and the number of employees amounted to 22,500, accounting for 18.65% of the number of rural employees in that year. Many departments were involved in the personnel management of these posts, such as gardening, social security, and municipal administration. The main financial source includes special funds allocated by municipal or district governments each year, which are uncertain regarding long-term disbursement. The foresaid “post” is a cautious naming, as these posts are informal ones that are temporary and unstable. The participants can only choose one of them under the government’s arrangement. The grain-to-green projects aim to transform the less productive sloping fields into woodland or grassland, involving 84,000 mu (one mu is approximately 0.0667 hectares) of land in total. According to the current subsidy standard, 35 kilos of flour and 20 yuan are provided per mu each year. On the premise of maintaining the ecological function of the farmland, the participating farmers shall reserve the right to further develop and utilize the land, and undertake the obligation to conserve trees. Plain afforestation emphasizes air purification and rainwater retention. The government acquires the operation rights of the plain land directly at a similar market land circulation price and then transforms the agricultural land into ecological land for reforestation. The land of Yanqing involved in plain afforestation, which includes mainly village-level land and the land with certified contractual rights, covered an area of 79,000 mu in 2016, with the land circulation price reaching 1000 yuan per mu each year. According to the maximum term of land contracts in Yanqing, the subsidy term of plain afforestation stipulated by the contracts is tentatively set to expire in 2027.

3.2. Questionnaire Survey

The research data were collected through a questionnaire survey in the Yanqing District, Beijing in 2016. Yanqing has a total of 15 towns. At the village-level and peasant household level, sample villages and sample farmers at home were selected according to the principle of stratified random sampling, of which two sample villages were selected from each sample township, and 45 sample farmers (aged between 16 and 64) were selected from each sample village. A total of 1350 questionnaires were obtained, of which 1279 were valid, and the validity of the questionnaire was 94.74%. In the selected sample villages, the first sample was chosen by randomly generating a number in an order in the roster, and then equidistant sampling was conducted to obtain other samples. If some respondents could not participate in the questionnaire survey after many attempts, a new sample would be selected instead by sampling. Due to the low educational level of the respondents, the questionnaires were filled out by the researchers, who did not incorporate any actions or words that might affect the results of the survey. Four aspects were involved in the questionnaires: (1) personal information, including gender, age, education, marital status, health, labor skills, location of employment, income of employment and industry type; (2) household information, including income and expenditure, agricultural and forestry production, social capital, material capital and dependency burden; (3) community information, including the average income level of the village, industrial structure, employment structure, topography, geographical location and natural environment characteristics; and (4) the ecological compensation projects that farmers participate in, including project type, project duration, compensation method, and amount, as well as the form of participation.

3.3. Empirical Model

In the empirical model, the dummy variable of whether rural labor is subject to transfer employment is taken as the explained variable. The laborers of transfer employment are characterized by part-time employment and mobility, and most of them are not completely separated from the agricultural industry. Some of them continue to engage in agricultural production after work or on vacation, and some undertake seasonal jobs by being engaged in agricultural production in busy farming seasons and in non-agricultural jobs in other periods. In terms of the transfer employment of rural labor, its fundamental aim is to acquire high income in the short term, and engagement in non-agricultural work for 3 months or 6 months is taken as the corresponding criterion in most of the existing research [32]. Based on the characteristics of the transfer employment of rural labor in China, this paper takes the accumulation of 6 months of non-agricultural labor income above the minimum wage standard as the measurement index of transfer employment. As regulated by the Beijing Municipal Human Resources and Social Security Bureau, the minimum monthly wage in Beijing was 1890 yuan in 2016. Thus, the rural labor force whose annual non-agricultural labor income is higher than 11,340 yuan in the sample is taken as the rural transfer employment labor force.

Moreover, two types of ecological compensation projects are taken as the major explanatory variables of the empirical model. The land-based projects of ecological compensation downsize agricultural production, causing labor surplus to a certain extent. Hence, whether the surplus labor could be transferred to other industries for employment is the focus of the empirical model in this research. Grain-for-green and plain afforestation projects are selected, which target different land types, i.e., the sloping land with lower productivity and the land in the plain area with higher productivity, respectively. Due to their large differences in productivity and labor intensity, these two land types are distinguished by dividing them into ecological compensation projects for cultivated land and those for forest land. Farmers participate in grain-for-green and plain afforestation projects in the form of households, the change in the land use patterns of which eventually influences the labor decisions of household members. For this reason, the number of mu of grain-for-green and those of plain afforestation of the households to which the samples belong are chosen as explanatory variables. Post-based projects of ecological compensation can provide job opportunities, which, however, are still temporary and unstable at present and hence cannot satisfy the requirement for high-quality employment. Thus, whether the participants of such post-based projects could further expand their employment channels is focused on in the model, and post subsidies for these projects are not incorporated into the income from non-agricultural work, so that the model can reflect how corresponding participants make other non-agricultural labor decisions. In addition, the dummy variable of whether individuals participated in the post-based project is taken as an explanatory variable.

Factors associated with individual, household, and community levels are also introduced into the empirical model as control variables. Individual factors mainly include age, years of education, gender, marital status, health status, and non-agricultural labor skills. There is a nonlinear relationship between age and transfer employment, so the model introduces the square term of age as a variable. Health status is described by the self-reported health level because laborers make employment decisions based on their self-perceived health levels rather than their actual health levels. Non-agricultural labor skills refer to the labor skills related to the secondary industry (skills in industries and construction, such as masons, bricklayers, cement workers, and painters) and the tertiary industry (skills in such aspects as sewing, machine operating, trading, driving, and cooking). Household factors include size, dependency load, planting situation, social capital, and the initial income of households. Specifically, household size is measured by the number of household members whose economy and life are integrated with the household. In the survey, these data were collected by asking whether respondents had lived at home for over three months or kept and spent money together. The household dependency load is measured by the number of the elderly and children to be cared for in the household. Planting situation is measured by the number of mu of arable land actually cultivated by the household. The influence of forestry production is ignored here due to the small labor force needed by forestry and the poor influence of changes in the scale of forestry production on the transfer employment of rural labor. The numbers of party members or cadres in the household are used to measure household social capital. The previous year’s gross income is to measure initial household income. Furthermore, the square of gross income is introduced to explore the nonlinear relationship between transfer employment and household initial income. Since rural laborers living in the same community are assumed to be faced with the same community factors, their differences at the community level are controlled by introducing the dummy variable of village.

On this basis, the final empirical model established here is depicted in Equation (1), with the variable definitions and descriptive statistics given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definitions and descriptive statistics of variables.

4. Results

4.1. The Model Presents Good Significance and Robustness

Since the explained variable is a dummy variable of whether the rural labor force is transferred to employment, the binary Logit model is used for estimation, and the estimation results are shown in Table 2. In models (1) and (2), only individual factors are taken into account, on the basis of which household factors, ecological compensation project factors, and the village dummy variable are added in models (3) and (4), models (5) and (6), as well as models (7) and (8), respectively. The final regression results are revealed by models (7) and (8). The estimation results from model (1) to model (8) are relatively stable, and the estimation results of robust standard error and ordinary standard error are basically consistent. With the increase in explanatory variables, the pseudo coefficient of determination R2, the probability of accurate estimation, likelihood ratio (LR) statistics and Wald statistics increased steadily from 0.25 to 0.41, from 73.89% to 81.63%, from 423.26 to 709.75, and from 271.16 to 381.76, respectively. Of 17 explanatory variables, 12 passed the significance test, with eight at the 0.1% level, two at the 1% level, and two at the 5% level. Overall, the estimated results exhibit good robustness and high accuracy.

Table 2.

Estimation results of the impact of ecological compensation project on rural labor transfer employment by the binary Logit model.

4.2. Ecological Compensation Project Has No Positive Effect in Promoting Rural Labor Transfer Employment

According to the estimated results of ecological compensation projects, the results of post-based projects are significantly less than 1 at a level of 0.1%, revealing that such projects limit participants’ engagement in other forms of non-agricultural work. One possible explanation is that participants in these projects are required to be on duty within the time specified, so they could not undertake the project tasks and other non-agricultural work simultaneously. The reduction in other non-agricultural work is acceptable for participants if the post-based projects continue to offer high-quality employment opportunities. However, the existing post-based projects remain temporary, unstable and insufficient, and fail to provide high-quality employment opportunities. Though these projects are able to provide some employment opportunities in the short term, they are unable to improve the human capital of participants in the long term, thus further leading to their weak employability in the market and dependence on these post-based projects. Specifically, once the projects come to an end, participants are likely to become surplus laborers again. In addition, no significant estimated results are obtained by land-based projects, indicating the absence of significant increases in non-agricultural employment after the transformation of agricultural land to ecological land. Although land-based ecological compensation projects have a certain pushing effect on rural labor transfer employment (the transformation of agricultural land into ecological land reduces agricultural labor opportunities and increases agricultural surplus labor), the pulling effect to promote rural labor transfer and employment is insufficient (because non-agricultural employment opportunities are limited, and all surplus agricultural labor cannot be transferred to non-agricultural jobs). The participants, who fail to find suitable employment opportunities, may adopt the previous agricultural production methods to re-cultivate the restored land once the project subsidies end. Overall, the performance of post-based and land-based projects in promoting the transfer employment of rural labor is not good, and heavy subsidies are needed to maintain the current ecological restoration effect.

4.3. Individual and Household Factors Have a Certain Influence on Rural Labor Transfer Employment

In terms of the individual and household factors, the estimated results of age and its square are significantly greater than 1 and less than 1, respectively, indicating the existence of an inverted U-shaped relationship, rather than a simple linear relationship, between age and the transfer employment of rural labor. The inflection point at 40 years old suggests that, when the age of the labor force is below this point, the older the age is, the higher the possibility of transferring employment would be, and vice versa when the age of the labor force is above this point. This analysis shows that the young and middle-aged labor force is the main body of rural labor transfer employment, and the older labor force encounters more obstacles in transfer employment. The estimated results of years of education and non-agricultural labor skills are significantly greater than 1, indicating that there is a significant positive relationship between these two factors and the transfer employment of rural labor. More than half of the rural labor force is employed in the tertiary industry in the study area. Due to the greater demand of this industry for a highly educated and highly skilled labor force, educational background and skills become significantly advantageous factors in the transfer employment of rural labor. In addition, the results also show that male, healthy, married rural labor has a higher possibility of transfer employment. According to the estimated result of the household scale being significantly lower than 1, the larger the household scale of the labor force is, the lower the possibility of transfer employment would be. This is possibly because more members generate income for the household, weakening the incentive for the laborer to raise their income through transfer employment. The estimated results of the previous-year household gross income and its square are higher than 1 and lower than 1 at a significant level, respectively, suggesting an inverted U-shaped relationship between the initial household income and the transfer employment of rural labor, with an inflection point at 127,700 yuan. Specifically, when the household income is below this point, the higher the household income is, the greater the possibility of transfer employment would be. On the contrary, when it is above this point, the higher the household income is, the lower the possibility of transfer employment to increase the household income would be. The estimated result of the amount of arable land actually cultivated by the household is significantly lower than 1, revealing a negative relationship between the planting industry and the transfer employment of rural labor, which may be caused by the need for a larger labor force in the planting industry.

In general, individual factors such as age, education level, gender, health status, marital status and labor skills significantly affect the transfer employment of the rural labor force. However, the impact of family factors on rural labor transfer employment is different. Among them, the size of the family population, family income and family arable land significantly affect rural labor transfer employment, while the number of older people and children in the family, and whether there are party members in the family, have no significant impact on rural labor transfer employment. The participants of the post-based ecological compensation project also increase their engagement in other non-farm activities while participating in the ecological compensation post, which means that the current employment post cannot fully meet the non-farm employment demand of farmers, and farmers need to find other employment opportunities. The analysis results of the two forms of land ecological compensation projects are not significant, that is, farmers cannot continue to engage in agricultural production after agricultural land is transformed into ecological land, and they cannot find other suitable non-agricultural labor opportunities.

5. Discussion

This paper reclassifies ecological compensation projects from the perspective of farmers, and comprehensively investigates the impact of different implementation methods of ecological compensation projects on rural labor transfer and employment. The existing studies mainly focus on a single ecological compensation project, and there is no comparative analysis of the implementation effects of different types of ecological compensation projects. In fact, in the implementation areas of ecological compensation projects in China, local farmers could participate in various types of ecological compensation projects at the same time. Therefore, based on the types of projects that farmers can choose to participate in, this paper divides ecological compensation projects into post-based types and land-based types. In the process of investigation, we also noticed that farmers implement different land management methods for land that is converted to grain-for-green and plain afforestation. Before the implementation of the ecological compensation project, farmers invested little in the land to be converted to grain-for-green. Therefore, this paper further subdivides land ecological compensation projects into plain afforestation and grain-for-green projects, so as to measure the impact of different land use changes on farmers in more detail. Compared with previous studies [33,34], the advantage of such classification is that it can further clarify which type of ecological project can achieve better livelihood effects for farmers with different characteristics (e.g., age, education, gender, etc.), thus helping the government to arrange ecological compensation funds reasonably. In addition, compared with official statistics and geospatial data, the survey data of rural laborers used in this paper can more accurately reflect the effects of ecological compensation projects at the micro scale.

There are also some limitations in this paper. Only one year of survey data is used in this study, but the rural ecological environment and economic development are constantly changing. Therefore, in the future, we can further attempt to establish a model that includes farmer’s production and consumption as well as labor supply behavior, and dynamically investigate the direct and indirect relationship between ecological compensation, farmers’ behavior and the ecological environment.

6. Conclusions and Implications

6.1. Conclusions

Based on the survey data of 1279 rural laborers from 30 villages in 15 towns in the Yanqing District of Beijing, this study takes the industrial transfer of the rural labor force as an important indicator of transfer employment to analyze the impact of post-based and land-based ecological compensation projects on rural labor transfer employment from the perspective of cultivating the self-development capability for the positioning of ecological functions. As indicated by the research results, land-based projects downsize agricultural production and reduce the agricultural production activities of participants, without significantly increasing their possibility of transfer employment. Since the quality of the posts offered is not high, post-based ecological compensation projects fail to facilitate participants to improve their human capital, while weakening their initiative to further expand their employment channels. In this paper, the problems of social and economic development and ecological environmental protection in rural areas are brought into a unified analysis framework, and the ecological compensation theory is integrated and improved from the two aspects of ecology and livelihood, which is conducive to promoting ecological compensation to play a better role in reality.

In view of the ecological sensitivity and ecological location importance of the Yanqing District, the case area selected for this study, many ecological compensation policies, projects, and activities have been implemented in this area. The ecological compensation project in the Yanqing District is not only a single financial transfer payment, but also a combination of various types of ecological compensation projects. Therefore, the results of this study can also be applied to other areas in China with rich ecological resources and diverse ecological compensation programs. In addition, we designed the questionnaire survey based on the perspectives of local farmers. In order to facilitate comparative analysis among farmers, the selection of interviewees was very comprehensive. The interviewees included farmers who participated in the ecological compensation program and those who did not. The interviewees also included farmers engaged in agricultural production, part-time households engaged in both agriculture and non-agriculture, and non-farmers who had left agriculture. This ensured the accuracy of the analysis results presented in this paper.

6.2. Implications

As shown in the empirical analysis results, it seems that the ecological compensation project makes farmers “lazy”. The land-based ecological compensation projects implemented have no significant impact on the transfer employment of farmers. After being released from agricultural work, participants of land-based ecological compensation projects cannot find other suitable jobs, that is, after the farmers’ agricultural land is transformed into ecological land, the participants’ off-farm employment dose not increase significantly. From an employment perspective, the rural areas in which ecological compensation projects are implemented do not cultivate the farmers’ self-development capability based on the positioning of ecological functions by utilizing the external support of “compensation”. Instead, the current ecological restoration effect is mainly maintained by policy subsidies. If the inherent demand and endogenous mechanism cannot be formulated in rural areas for environmental protection, the effect of ecological restoration projects, even if they are implemented by some villages on a large scale and under strong external investment, may not last in the long run.

According to the experience of economic development, non-agricultural activities in rural areas provide the premise for changes in land use patterns [35,36,37]. At present, land-based ecological compensation projects reversely drive the structural transformation of agricultural production through changes in land use patterns, while the feasibility of this logic remains questionable. Serious and extensive considerations should be made in terms of land use since land is the most precious resource in rural areas [38,39]. Participants in land-based ecological compensation projects, who have no other suitable employment opportunities, are likely to adopt environmentally unfriendly production practices on land that has been converted to forestry, eventually destroying the ecological restoration effect achieved. Therefore, for the labor force remaining in rural areas, in addition to creating jobs to promote their transfer employment, it is also necessary to improve their own employability and strengthen the investment in human capital such as education and training.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.D. and J.G.; methodology, H.D.; software, J.G.; validation, H.D., J.G., and Z.W.; formal analysis, H.D.; investigation, J.G.; resources, H.D.; data curation, J.G.; writing—original draft preparation, J.G.; writing—review and editing, H.D.; visualization, Z.W.; supervision, H.D.; project administration, H.D.; funding acquisition, H.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Youth Scientific Research Fund project of Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences, Grant No. QNJJ202220; the Collaborative Innovation Platform Construction Project of Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences, Grant No. KJCX201913; and the Additional Financial Special Project of Beijing Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences, Grant No. CZZJ202201.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Acknowledgments

All authors thank the anonymous reviewers and the editor for their constructive comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alix-garcia, J.; Wolff, H. Payment for ecosystem services from forests. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2014, 6, 361–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, S.; Ouyang, Z.; Tam, C.; Chen, X. Ecological and socioeconomic effects of China’s policies for ecosystem services. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 9477–9482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolinjivadi, V.K.; Sunderland, T. A review of two payment schemes for watershed services from China and Vietnam: The Interface of government control and pes theory. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groom, B.; Palmer, C. REDD+ and rural livelihoods. Biol. Conserv. 2012, 154, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Gong, J.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Y. The causal pathway of rural human settlement, livelihood capital, and agricultural land transfer decision-making: Is it regional consistency? Land 2022, 11, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X. The Life of Jiangcun Peasants and Its Vicissitude; Dunhuang Literature and Art Publishing House: Dunhuang, China, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Jin, L. How Eco-compensation contribute to poverty reduction: A perspective from different income group of rural households in Guizhou, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 122962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, T. Conservation reserve program: Status and current issues. Congr. Res. Serv. Rep. 2010, 54, 439–444. [Google Scholar]

- Claassen, R.; Cattaneo, A.; Johansson, R. Cost-effective design of agri-environmental payment programs: U.S. experience in theory and practice. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 737–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, A.P.; Gramig, B.M.; Prokopy, L.S. Farmers and conservation programs: Explaining differences in environmental quality incentives program applications between states. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2013, 68, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbs, T.L.; Pretty, J. Case study of agri-environmental payments: The United Kingdom. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 765–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmford, A.; Bruner, A.; Cooper, P.; Costanza, R.; Farber, S.; Green, R.E.; Jenkins, M.; Jefferiss, P.; Jessamy, V.; Madden, J.; et al. Economic reasons for conserving wild nature. Science 2002, 297, 950–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schilizzi, S.; Latacz-Lohmann, U. Assessing the performance of conservation auctions: An experimental study. Land Econ. 2007, 83, 497–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baylis, K.; Peplow, S.; Rausser, G.; Simon, L. Agri-environmental policies in the EU and United States: A comparison. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, S.; Pagiola, S.; Wunder, S. Designing payments for environmental services in theory and practice: An overview of the issues. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.J.; Si, W.; Liu, Z.Q.; Li, C.Z.; Zhang, Y.Y. Polycentric governance of government- led ecological compensation: Based on the perspective of farmers’ social network. Resour. Sci. 2020, 42, 812–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, M.T. China’s sloping land conversion program: Institutional innovation or business as usual? Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Wang, A.; Liu, X.; Xu, G. Comparative study of international farming and animal husbandry ecological compensation and its implications. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2018, 32, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liu, J.; Fu, B.; Wang, S.; Wei, Y. Integrating multiple influencing factors in evaluating the socioeconomic effects of payments for ecosystem services. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 51, 101348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, E.; Xu, J.; Rozelle, S. Grain for green: Cost-effectiveness and sustainability of China’s conservation set-aside program. Land Econ. 2005, 21, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, F.; Chen, Z. Impact of SLCP on off-farm job. China Soft Sci. 2006, 8, 31–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Q.; Fang, J.; Li, X.; Su, F. Impact of Ecological Compensation on Farmers’ Livelihood Strategies in Energy Development Regions in China: A Case Study of Yulin City. Land 2022, 11, 965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Xia, F.; Chen, Q.; Huang, J.; He, Y.; Rose, N.; Rozelle, S. Grassland ecological compensation policy in China improves grassland quality and increases herders’ income. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, S.; Peng, J.; Zheng, H.; Xu, Z.; Meersmans, J. How can massive ecological restoration programs interplay with social-ecological systems? A review of research in the South China karst region. Sci Total Environ. 2020, 807, 150723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, F.; Zhang, Q.; Hong, J.; Dong, C. Is it sustainable to implement a regional payment for ecosystem service programme for 10 years? An empirical analysis from the perspective of household livelihoods. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 176, 106746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schokkaert, E.; Ootegem, L.V. Sen’s concept of the Living Standard applied to the Belgian Unemployed. Rech. Econ. De Louvain 1990, 56, 429–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Development as Freedom; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Klink, J.J.L.; Bültmann, U.; Burdorf, A.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Zijlstra, F.R.; Abma, F.I.; Brouwer, S.; van der Wilt, G.J. Sustainable employability—Definition, conceptualization, and implications: A perspective based on the capability approach. Scand. J. Work Environ. Health 2016, 42, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagoila, S. Can programs of payments for environmental services help preserve wildlife? Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Economic Incentives and Trade Policies, Geneva, Switzerland, 1–3 December 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, H.; Kandel, S.; Dimas, L. Compensation for environmental services and rural communities: Lessons from the Americas. Int. For. Rev. 2004, 6, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, W.; Yu, Z. Analyzing Farmers’ Perceptions of Ecosystem Services and PES Schemes within Agricultural Landscapes in Mengyin County, China: Transforming Trade-Offs into Synergies. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xie, F.; Zhang, H.; Guo, S. Influences on rural migrant workers’ selection of employment location in the mountainous and upland areas of Sichuan, China. J. Rural Stud. 2014, 33, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Geng, Y.; Guo, Y. Assessing Controversial Desertification Prevention Policies in Ecologically Fragile and Deeply Impoverished Areas: A Case Study of Marginal Parts of the Taklimakan Desert, China. Land 2021, 10, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ding, Z.; Yao, S.; Xue, C.; Deng, Y.; Jia, L.; Chai, C.; Zhang, X. How to Price Ecosystem Water Yield Service and Determine the Amount of Compensation?—The Wei River Basin in China as an Example. Land 2022, 11, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Bai, Y.; Alatalo, J.M. Impacts of rural tourism-driven land use change on ecosystems services provision in Erhai Lake Basin, China. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 42, 101081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Wu, J.; Yin, H.; Li, Z.; Chang, Q.; Mu, T. Rural Land Use Change during 1986–2002 in Lijiang, China, Based on Remote Sensing and GIS Data. Sensors 2008, 8, 8201–8223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, W.; Jiang, G.; Li, W.; Zhou, T. How do population decline, urban sprawl and industrial transformation impact land use change in rural residential areas? A comparative regional analysis at the peri-urban interface. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 205, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rammelt, C.F.; Van Schie, M.; Tegabu, F.N.; Leung, M. Vaguely right or exactly wrong: Measuring the (spatial) distribution of land resources, income and wealth in rural Ethiopia. Sustainability 2017, 9, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Z.; Wei, Y.; Li, X. Risk Perception of Rural Land Supply Reform in China: From the Perspective of Stakeholders. Agriculture 2021, 11, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).