A Three-Component Decomposition of the Change in Relative Poverty: An Application to China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Poverty and Its Measurement

2.2. Poverty Criteria and Poverty Lines

2.3. Decomposition of Poverty Change

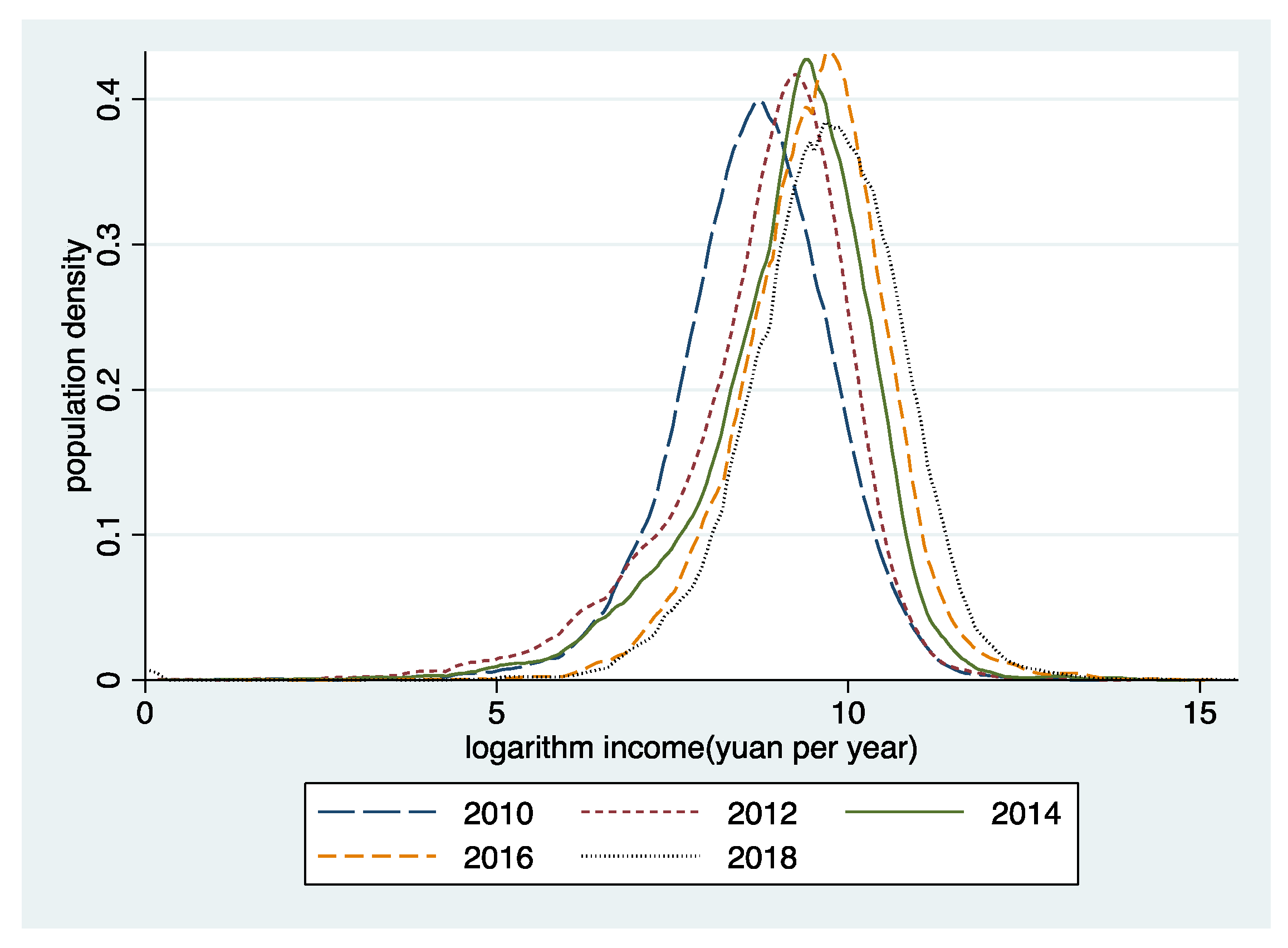

3. Measurement of Relative Poverty in China

3.1. Measurement

3.2. Comparison of Mean and Median

4. Decomposition of Changes in Poverty

4.1. Decomposition Method

4.2. Quantitative Decomposition of Poverty Changes in China: 2010–2018

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ravallion, M. On measuring global poverty. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2020, 12, 167–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Development Research Center of the State Council; World Bank. Four Decades of Poverty Reduction in China: Drivers, Insights for the World, and the Way Ahead; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Datt, G.; Ravallion, M. Growth and redistribution components of changes in poverty measures: A decomposition with applications to Brazil and India in the 1980s. J. Dev. Econ. 1992, 38, 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakwani, N. On measuring growth and inequality components of poverty with application to Thailand. J. Quant. Econ. 2000, 16, 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Shorrocks, A.F. Decomposition procedures for distributional analysis: A unified framework based on the Shapley value. J. Econ. Inequal. 2013, 11, 99–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sen, A. Commodities and Capabilities; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, P. Poverty in the United Kingdom: A Survey of Household Resources and Standards of Living; Penguin Books: London, UK, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Ravallion, M. Reconciling the conflicting narratives on poverty in China. J. Dev. Econ. 2021, 153, 102711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravallion, M.; Chen, S. Welfare-Consistent Global Poverty Measures; NBER Working Paper; NBER: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, T.; Su, W. Strategic orientation and policy option on the governance of relative poverty in the context of rural revitalization. J. Xinjiang Norm. Univ. 2020, 41, 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.; Zhu, F.; Liu, W. Research progress on deep poverty from a structural perspective. Econ. Perspect. 2020, 2, 132–145. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Zhang, Q. The criteria for measuring relative poverty in post-2020 China: Experience, practice, and theory. J. Xinjiang Norm. Univ. 2021, 42, 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Li, S. How to determine the standards of relative poverty after 2020?—With Discussion on the feasibility of “urban-rural coordination” in relative poverty. J. South China Norm. Univ. 2020, 2, 91–101. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Sun, J. China’s relative poverty standards, measurement and targeting after the completion of building a moderately prosperous society in an all-round Way: An analysis based on data from China urban and rural household survey in 2018. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2021, 3, 2–23. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Yu, X.; Li, F. The standard definition and scale measurement of China’s relative poverty. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2021, 1, 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Y. Governance of rural relative poverty: Measurement principle and path choice. Theory J. 2021, 4, 142–149. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L. International experience and insight of relative poverty standard. Frontiers 2020, 14, 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- Ravallion, M. On the Origins of the Idea of Ending Poverty; NBER Working Paper; NBER: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ravallion, M.; Chen, S. China’s (uneven) progress against poverty. J. Dev. Econ. 2007, 82, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ali, A.A.G. Dealing with poverty and income distribution issues in developing countries: Cross-regional experiences. J. Afr. Econ. 1998, 7 (Suppl. S2), 77–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorrocks, A.; Kolenikov, S. Poverty Trends in Russia during the Transition. Mimeograph; World Institute for Development Economics Research (WIDER): Helsinki, Finland; University of North Carolina: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Baye, F.M. Growth, redistribution and poverty changes in Cameroon: A Shapley decomposition analysis. J. Afr. Econ. 2006, 15, 543–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Liu, S. Income structure, income inequality, and rural family poverty. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2017, 8, 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Fujii, T. Dynamic Poverty Decomposition Analysis: An Application to the Philippines. World Dev. 2017, 100, 69–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aristondo, O.; Ambrosio, C.D.; de la Vega, C.L. Decomposing the Changes in Poverty: Poverty Line and Distributional Effects. Manuscript. Available online: http://www.ecineq.org/ecineq_paris19/papers_EcineqPSE/paper_411.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2021).

- Luo, L.; Ping, W. Decomposition of poverty dynamic changes in China: 1991~2015. Manag. World 2020, 36, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Sheshinski, E. Relation between a social welfare function and the Gini index of income inequality. J. Econ. Theory 1972, 4, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Real national income. Rev. Econ. Stud. 1976, 43, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravallion, M.; Chen, S. Global poverty measurement when relative income matters. J. Public Econ. 2019, 177, 104046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mesnard, L. Poverty Reduction: The Paradox of the Endogenous Poverty Line (No. 2007–05; Economy). 2007. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1029245 (accessed on 16 December 2021).

- Kampke, T. The use of mean values versus medians in inequality analysis. J. Econ. Soc. Meas. 2010, 35, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootaert, C. Structural change and poverty in Africa: A decomposition analysis for Côte d’Ivoire. J. Dev. Econ. 1995, 47, 375–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Literature | Whether Consider Change in Poverty Line | Type of Poverty Lines | Decomposition Frame | Whether There Is Residual | Countries | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Datt and Ravallion (1992) | No | Absolute | Growth-distribution | Yes | Brazil and India | Incomplete decomposition |

| Ali (1998) | Yes | Strongly relative | Growth-distribution | No | Latin America, Asia, and South Sahara Africa | Growth component not complete |

| Shorrocks and Kolenikov (2001) | Yes | Absolute | Growth-distribution-poverty line | Yes | Russia | Incomplete decomposition |

| Baye (2006) | No | Absolute | Growth-distribution | No | Cameroon | Poverty line change not considered |

| Shorrocks (2013) | No | Absolute | Growth-distribution | No | - | Poverty line change not considered |

| Fujii (2017) | Yes | Strongly relative | Growth-distribution | No | The Philippines | Poverty line change not considered |

| Aristondo et al. (2019) | Yes | Strongly relative | Poverty line-growth-inequality | No | 27 European countries | Some results inconsistent |

| Jiang and Liu (2017) | No | Absolute | Growth-distribution | Yes | China | Poverty line change not considered |

| Luo and Ping (2020) | No | Absolute | Growth-inequality-population | No | China | Poverty line change not considered |

| This paper | Yes | Endogenous relative lines | Identification-growth-redistribution | No | China | Complete decomposition and poverty line change considered |

| Year | 2010 | 2012 | 2014 | 2016 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30% of the mean [median] | 3076 [1800] | 4028 [2700] | 5270 [3240] | 7381 [4320] | 10,093 [5000] |

| 50% of the mean [median] | 5127 [3000] | 6713 [4500] | 8784 [5400] | 12,301 [7200] | 16,821 [8333] |

| Year | 2010 | 2012 | 2014 | 2016 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relative poverty standard | 30% of the mean [median] | 25.88 [12.94] | 24.14 [16.95] | 27.03 [16.95] | 25.33 [13.18] | 32.75 [12.30] |

| 50% of the mean [median] | 43.98 [24.71] | 38.54 [26.71] | 41.50 [27.60] | 43.57 [24.82] | 50.54 [24.99] |

| Periods | Poverty Index (P, %) | Poverty Changes | Identification Component | Growth Component | Redistribution Component |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010–2012 | Absolute poverty incidence | ↑8.22 | 7.74 | −13.01 | 13.49 |

| Relative poverty incidence | ↓5.44 | 8.26 | −11.07 | −1.89 | |

| 2012–2014 | Absolute poverty incidence | ↓1.42 | 0.74 | −17.74 | 15.58 |

| Relative poverty incidence | ↑2.96 | 8.42 | −8.34 | 2.88 | |

| 2014–2016 | Absolute poverty incidence | ↓7.30 | 0.44 | −20.81 | 13.07 |

| Relative poverty incidence | ↑2.07 | 12.19 | −11.24 | 1.12 | |

| 2016–2018 | Absolute poverty incidence | ↓1.41 | 0.03 | −19.04 | 17.60 |

| Relative poverty incidence | ↑6.97 | 12.55 | −12.18 | 6.60 |

| Periods | Contribution Degree (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute Poverty | Relative Poverty | |||||

| Identification Component | Growth Component | Redistribution Component | Identification Component | Growth Component | Redistribution Component | |

| 2010–2012 | 22.61 | −38.00 | 39.40 | 38.93 | −52.17 | −8.91 |

| 2012–2014 | 2.17 | −52.08 | 45.74 | 42.87 | −42.46 | 14.66 |

| 2014–2016 | 1.28 | −60.64 | 38.08 | 49.65 | −45.78 | 4.56 |

| 2016–2018 | 0.08 | −51.92 | 48.00 | 40.06 | −38.88 | 21.07 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fan, Z.; Zou, W. A Three-Component Decomposition of the Change in Relative Poverty: An Application to China. Land 2023, 12, 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12010205

Fan Z, Zou W. A Three-Component Decomposition of the Change in Relative Poverty: An Application to China. Land. 2023; 12(1):205. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12010205

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Zengzeng, and Wei Zou. 2023. "A Three-Component Decomposition of the Change in Relative Poverty: An Application to China" Land 12, no. 1: 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12010205