Community Drawing and Storytelling to Understand the Place Experience of Walking and Cycling in Dushanbe, Tajikistan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Rationale for the Study

1.1.1. Transit as an Element of Sustainable Landscapes and Green Recovery

1.1.2. Road Safety in Tajikistan and Dushanbe

1.1.3. Contribution of the Present Study

1.2. The Study Area

1.2.1. Dushanbe, Capital City of Tajikistan

1.2.2. Wider Geographical Context

1.3. Literature Review

1.3.1. Understanding Locations and Routes as Places

1.3.2. Cultural Ecology, Community Participation, and Creative Experiences

1.3.3. The Case for Storytelling and Drawing

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Approach

2.2. Research Procedures

2.2.1. Drawing and Storytelling Workshops

- Can participants locate on neighborhood maps, areas, nodes, and routes of notable non-auto experience while walking and/or cycling?

- Nodes are specific locations, such as corners, junctions, and crossing places.

- Areas are larger spaces such as street frontages, parks, gardens, and so on.

- Routes are linear spaces used to move to and from destinations in a neighborhood such as roads, streets, alleys, and paths.

- Areas, nodes, and routes are not mutually exclusive. Students can co-mingle these locations on a map.

- Notable non-auto experiences can be based on actual events, and/or perceptions and feelings.

- Participants are encouraged to draw how they feel, to help them describe their perspective.

- Drawings of how participants feel can be on the same maps used for locating experiences, new maps, or plain paper.

- Drawings can be literal and representative of the physical spaces where experiences occur.

- Drawings can be abstract and expressive of feelings and moods.

- Drawings can be a mixture of literal and abstract.

- All drawings should include written descriptions to aid interpretation and collation.

- YGT staff should be available to participants to answer questions and listen to stories as they draw, encouraging them to develop their ideas.

- Participants should be accommodated in small groups of five to encourage talking, and exchange of ideas and thoughts.

- Drawings should not be treated as “art”.

- Tell students that their work will be scanned and shared, but because of the stories they tell, not because of their artistic technique.

- Drawings are not “exhibited” on a wall for the larger group to share.

- Drawings can be shared among students in a sub-group, but no one must share their drawn work during the workshop.

2.2.2. Ground-Truthing through Stakeholder Semi-Structured Interviews

3. Results

3.1. Drawing and Storytelling Workshops

3.1.1. Descriptive Statistics of Participants

3.1.2. Inductive Content Analysis of Transcribed Participants’ Stories and Experiences

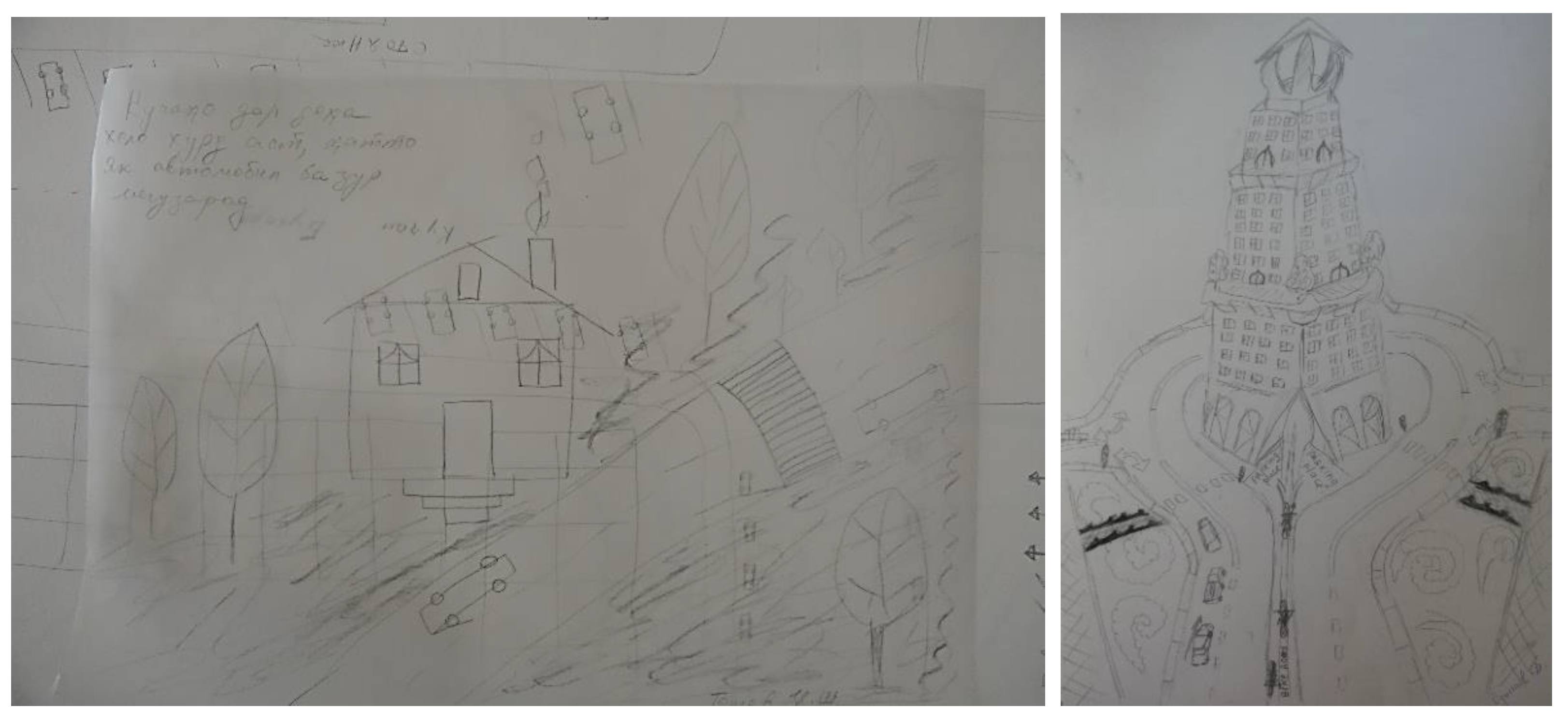

3.1.3. Participants’ Workshop Drawings

3.2. Ground-Truthing through Stakeholder Semi-Structured Interviews

“Due to economic factors, young people are more likely to travel as pedestrians and cyclists.

Therefore, they are inherently more at risk by virtue of their socio-economic status and an absent safe system designed to protect them. Traditional arguments also suggest that young males tend to take more risks when they do drive [and] due to their socio-economic status, young males use older ‘cheaper’ cars which lack modern safety standards.”- Eastern Alliance for Safe and Sustainable Transport Staff Member

“As a developing country in [post-Soviet] transition, investment has focused on building road infrastructure, leading to far higher speeds on highways and urban roads.”- Eastern Alliance for Safe and Sustainable Transport Staff Member

Again, cyclists do not consider as an equal road user, drivers are poorly trained both theoretically and practically. Lack of infrastructure is also the main point.- Young Generation of Tajikistan Staff Member

“EASST was established [in London] in 2009 to nurture homegrown expertise and leadership in a region with a shared history and common need to improve road safety and mobility. EASST’s core ethos is that local ownership of an issue is essential for sustainable change. Sending in international experts is not enough—local expertise, champions and leadership are vital.”- Eastern Alliance for Safe and Sustainable Transport Staff Member

“Community programs [that are] trying to transform the [region’s] cities for cyclists and pedestrians [while] simultaneously working with [international] programs, trying to project foreign experience in local realities [that] is necessary to increase cycling culture in society.”- Young Generation of Tajikistan Staff Member

“[While] you can help people learn road safety and pedestrian safety by modeling safe behavior, having safety rules, and teaching children safety… we need to slow cars, create separated places for people walking and biking, transit networks, not just isolated pieces of sidewalk or bike lane.”- Young Generation of Tajikistan Staff Member

“It is important what came to us from our good Soviet past, something that contains history… [But] unfortunately, [public participation is currently] very low and they do not take an active part in the life of the city, or at least their voice can’t be heard.”- Young Generation of Tajikistan Staff Member

“As far as I am aware, there is very little formal community engagement or public participation. There is no opportunity and channels for public participation, and they are not often consulted. In some instances, stakeholder engagement is carried out but this is usually conducted poorly, often by international consultants with little understanding of who the local stakeholders are, or it’s done after the fact. Certainly not in the planning and design stages.”- Eastern Alliance for Safe and Sustainable Transport Staff Member

“The workshop engagement could ensure that the community is part of a planning and decision-making process of a project, and that their values, needs, and wants are being reflected in what’s constructed and planned around them.”- Young Generation of Tajikistan Staff Member

“[The workshops were] the first time anything like this has been done in Tajikistan. The workshops have given participants the opportunity and encouragement to think about road issues from a completely new perspective. My hope is that it has given them a new understanding of what road safety means, and given them the confidence to understand a systems approach, and to envisage how things could be if vulnerable road users were prioritized and the needs of local road users were considered in the design process. I hope it has encouraged them to not just accept the status quo of “more roads”, and think about the need to update local road standards.”- Eastern Alliance for Safe and Sustainable Transport Staff Member

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, C.; Clayden, A.; Dunnett, N. An Exploration of the Effect of Housing Unit Density on Aspects of Residential Landscape Sustainability in England. J. Urban Des. 2009, 14, 163–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fears, R.; Gillett, W.; Haines, A.; Norton, M.; Ter Meulen, V. Post-pandemic recovery: Use of scientific advice to achieve social equity, planetary health, and economic benefits. Lancet Planet. Health 2020, 4, E383–E384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, A. The Year of the Superstudio. Land. Arch. Mag. 2002. Available online: https://landscapearchitecturemagazine.org/2022/04/07/the-year-of-the-superstudio/ (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Landscape Institute. Greener Recovery: Delivering a Sustainable Recovery from COVID-19; LI Policy Paper; Landscape Institute: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Akbari, H.; Rose, L.S.; Taha, H. Analyzing the land cover of an urban environment using high-resolution orthophotos. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2003, 63, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Popkin, B.; Gordon-Larsen, P. A National-level Analysis of Neighborhood form Metrics. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 116, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Active Community Environments. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/aces.htm (accessed on 16 October 2022).

- European Commission. Horizon 2020. Work Programme 2014–2015 Smart, green and integrated transport “European Commission Decision C(2014)4995 of 22 July 2014 EU Research and Innovation Bulletin; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. Review of Road Safety in Asia and the Pacific; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Maas, T.; Lucas, P. Global Green Recovery: From Global Narrative to International Policy; PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Nations around the World are Planning for a Green Recovery. Available online: https://climate-xchange.org/2020/06/11/nations-around-the-world-are-planning-for-a-green-recovery-is-the-u-s-falling-behind (accessed on 9 September 2022).

- A Green Recovery. Bruegel Blog Post. Available online: https://www.bruegel.org/blog-post/green-recovery (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- Shaheen, S.; Wong, S. Future of Public Transit and Shared Mobility: Scenario Planning for COVID-19 Recovery; University of California, Institute for Transportation Studies: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 20 January 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Schröder, M.; Späth, P.; Freytag, T. Urban Space Distribution and Sustainable Transport. Transp. Rev. 2016, 36, 659–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, R.; Welsh, K. The road to “local green recovery”: Signposts from COVID- 19 lockdown life in the UK. Area 2022, 54, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Tajikistan’s Green and Resilient Recovery Agenda Central to World Bank Support. Press Release, 1 October 2021. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/10/01/tajikistans-green-and-resilient-recovery-agenda-central-to-world-bank-support (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- Adineh, E. Demolishing Dushanbe: How the Former City of Stalinabad is Erasing its Soviet Past. The Guardian, 19 October 2017. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/oct/19/demolishing-dushanbe-former-stalinabad-erasing-soviet-past#:~:text=Once%20known%20as%20Stalinabad%20(or,taking%20over%20from%20traditional%20bazaars(accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Griskeviciute-Geciene, A.; Griškevičiene, D. The Influence of Transport Infrastructure Development on Sustainable Living Environment in Lithuania. Procedia Eng. 2016, 134, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Koval, V.; Olczak, P.; Vdovenko, N.; Boiko, O.; Matuszewska, D.; Mikhno, I. Ecosystem of Environmentally Sustainable Municipal Infrastructure in Ukraine. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrkajić, V.; Anguelovski, I. Planning for sustainable mobility in transition cities: Cycling losses and hopes of revival in Novi Sad, Serbia. Cities 2016, 52, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofeska, E. Understanding the livability in a city through smart solutions and urban planning toward developing sustainable livable future of the City of Skopje. Procedia Env. Sci. 2017, 37, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swennen, B.; European Cyclists’ Federation. Skopje joins the Cities for Cycling network. News Bulletin, 5 August 2016. Available online: https://ecf.com/news-and-events/news/skopje-joins-cities-cycling-network#:~:text=In%20the%20heart%20of%20the,cycling%20cities%20in%20the%20Network(accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Sofeska, E.; Sofeski, E. Developing Projects for Realizing of the Program “Skopje 2020 Smart Strategy” by Enhancing Citizen Approach, Engineering, Digitalization, and Sensing of the City District Toward Smarter Sustainability Urban Potential in the Small Ring of Skopje. In Resilient and Responsible Smart Cities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicka, M. What makes neighborhood different from home and city? Effects of place scale on place attachment. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berleant, A. The Aesthetics of Environment; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Seamon, D. Place attachment and phenomenology. In Place Attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods and Applications; Manzo, L.C., Devine-Wright, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan, Y.-F. A View of Geography. Geogr. Rev. 1991, 81, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.; Belanger, B. Drawing Place. Reading List Places 2017. Available online: https://placesjournal.org/reading-list/drawing-place/?cn-reloaded=1 (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Casey, E.S. Getting Back into Place; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rowles, G. Habitation and being in place. Occup. Ther. J. Res. 2000, 20, 52S–67S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moores, S. Media, Place, and Mobility; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jungnickel, K.; Aldred, R. Cycling’s sensory strategies: How cyclists mediate their exposure to the urban environment. Mobilities 2014, 9, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesener, A.; Vallance, S.; Tesch, M.; Edwards, S.; Frater, J.; Moreham, R. A mobile sense of place: Exploring a novel mixed methods user-centred approach to capturing data on urban cycling infrastructure. Appl. Mobilities 2021, 7, 321–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wunderlich, F.M. Walking and Rhythmicity: Sensing Urban Space. J. Urban Des. 2008, 13, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybråten, S.; Skår, M.; Nordh, H. The phenomenon of walking: Diverse and dynamic. Landsc. Res. 2019, 44, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, T. Towards a politics of mobility. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2010, 28, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gustafson, P. Place attachment in an age of mobility. In Place Attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods and Applications; Manzo, L.C., Devine-Wright, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Manzo, L.C. Exploring the shadow side. In Place Attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods and Applications; Manzo, L.C., Devine-Wright, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 178–190. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, H.; Block, D.; Bosse AHawthorne, T.L.; Jung, J.; Pearsall, H.; Rees, A.; Shannon, J. Doing community geography. GeoJournal 2022, 87, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hester, R.T. Design for Ecological Democracy; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, R.; Booth-Kurpnieks, C.; Davies, K.; Delsante, I. Cultural ecology and cultural critique. Arts 2019, 8, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaszynska, P.; Crossick, G. Understanding the Value of Arts and Culture. 2016. Available online: https://www.artshealthresources.org.uk/docs/understanding-the-value-of-arts-culture-the-ahrc-cultural-value-project/ (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Wood, S.; Dovey, K. Creative multiplicities: Urban morphologies of creative clustering. J. Urban Des. 2015, 20, 52–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glăveanu, V.P.; Beghetto, R.A. Creative Experience: A Non-Standard Definition of Creativity. Creat. Res. J. 2021, 33, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anik, M.A.H.; Sadeek, S.N.; Hossain, M.; Kabir, S. A framework for involving the young generation in transportation planning using social media and crowd sourcing. Transp. Policy 2020, 97, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poplin, A. Playful public participation in urban planning: A case study for online serious games. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2012, 36, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, S.R. The Creative Process: A Computer Model of Storytelling and Creativity; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, W.R. Human Communication as Narration: Toward a Philosophy of Reason, Value, and Action; University of South Carolina: Columbia, SC, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Pstross, M.; Talmage, C.A.; Knopf, R.C. A story about storytelling: Enhancement of community participation through catalytic storytelling. Community Dev. 2014, 45, 525–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haklay, M.; Jankowski, P.; Zwoliński, Z. Selected modern methods and tools for public participation in urban planning–a review. Quaest. Geogr. 2018, 37, 127–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Kodmany, K. Using visualization techniques for enhancing public participation in planning and design: Process, implementation, and evaluation. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1999, 45, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.; Conley, M.; Latimer, B.; Ferrari, D. Co-Design: A Process of Design Participation; Van Nostrand Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- de Lima, E.S.; Feijó, B.; Barbosa, S.D.; Furtado, A.L.; Ciarlini, A.E.; Pozzer, C.T. Draw your own story: Paper and pencil interactive storytelling. Entertain. Comput. 2014, 5, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Oliveira, A.R.; Partidário, M. You see what I mean?A review of visual tools for inclusive public participation in EIA decision-making processes. EIA Rev. 2020, 83, 106413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brailas, A. Using Drawings in Qualitative Interviews: An Introduction to the Practice. Qual. Rep. 2020, 25, 4447–4460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, S.; Cresswell, K.; Robertson, A.; Huby, G.; Avery, A.; Sheikh, A. The case study approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blaxter, L.; Hughes, C.; Tight, M. How to Research; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, B. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, J. Doing Your Research Project: A Guide to First Time Researchers in Education and Social Sciences, 2nd ed.; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, M. A case study method for landscape architecture. Landsc. J. 2001, 20, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona, M. The Place-shaping Continuum: A Theory of Urban Design Process. J. Urban Des. 2014, 19, 2–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D. A General Inductive Approach for Qualitative Data Analysis. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, R.G. In the Field: An Introduction to Field Research; Routledge: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim, A.N. Questionnaire Design, Interviewing and Attitude Measurement, New 2nd ed.; Pinter Publishers: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

| Total N | Student | Working | Retired | Average Age | % Female/Male | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 24 | 7 | 15 | 2 | 30 | 25/75 |

| 2022 | 16 | 4 | 12 | 0 | 29 | 6/94 |

| Emergent Themes | Emergent Sub-Themes | Emergent Linking-Themes | Illustrative Participants’ Quotes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavior of drivers |

|

| “Car drivers often pin us down [and] drivers drive red lights.” “When you cross the road to green and a couple of seconds remain at the traffic light, half of the drivers start honking so that pedestrians start walking faster, because do not slow down the movement of cars.” “We live in a good area, but for young people it’s easier to cross a road. On occasion you can cross the road. What about seniors and people with disabilities; they cannot run across the road a great distance to the nearby underpass.” “Bicycle lane network is what we need in Dushanbe, it will not be enough to build two or three bike lanes, we need a whole network of bike lanes.” “For tourists this road looks like adventure especially when they are riding on JEEP but for locals it’s a big problem.” |

| Qualities of neighborhood and residential areas |

|

| “In the city center it is safer to go because there are a large concentration of police. As soon as you leave the center you need to be very careful.” “I feel terrible when I am coming back home. It’s all a mess, a lot of traffic and people, cars are buzzing, people are shouting.” “Our area belongs more and more to cars! Some people work and live not far away. They don’t need cars, they are just not walking.” “Our neighborhood streets are very small children riding bicycles and scooters there, and when one car passes, there is no space left for the roadway.” “We need more bike paths in our neighborhood streets where children and adults can ride bicycles safely inside the area.” |

| Emergent Themes | Emergent Sub-Themes |

|---|---|

| A longing for human scale in residential areas |

|

| Reconceptualization of vehicular traffic |

|

| The mental and physical health aspects of walking and cycling |

|

| The aspirational aspects of vehicular travel |

|

| Primary Interview Questions | Elicited Secondary Follow-Up Questions | Summary of Content of Responses |

|---|---|---|

| Generally, Tajikistan has a poor record of transport safety. This is also true of Dushanbe, specifically. Why do you think that this is the case? | Workshop participants suggested that driver behavior might be problematic; what can you tell me about that? |

|

| Tell me about how/why EASST/YGT become involved in road safety in Dushanbe through partnership with the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development |

| |

| What do you think are the most significant barriers and opportunities for improving road safety for pedestrians and cyclists in Dushanbe? | Workshop participants suggested low prioritization of pedestrians and cyclists. How do you feel about the current levels of cyclist and pedestrian prioritization in Dushanbe? |

|

| How do you feel about the possible future levels of cyclist and pedestrian prioritization in Dushanbe? |

| |

| How do the public feel about the redevelopment of Dushanbe in general? Specifically, the demolition of Soviet-era buildings and spaces? |

| |

| The outcomes of the workshops, suggest they could be useful methods for public engagement through a creative experience. What benefits do you think the drawing workshop approach has, and could bring to community engagement and public participation in the planning and design of urban areas, neighborhoods, and districts in Dushanbe? |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Smith, C.A. Community Drawing and Storytelling to Understand the Place Experience of Walking and Cycling in Dushanbe, Tajikistan. Land 2023, 12, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12010043

Smith CA. Community Drawing and Storytelling to Understand the Place Experience of Walking and Cycling in Dushanbe, Tajikistan. Land. 2023; 12(1):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12010043

Chicago/Turabian StyleSmith, Carl A. 2023. "Community Drawing and Storytelling to Understand the Place Experience of Walking and Cycling in Dushanbe, Tajikistan" Land 12, no. 1: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12010043