Contemporary Transformations of the Historic Urban Landscape of Sarajevo and Social Inclusion as a Traditional Value of a Multicultural Society

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review Related to the Historical Landscape in General

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results—Historic Urban Landscape of Sarajevo: Its Values and Transformations

4.1. Adoption of the Historic Urban Landscape of Sarajevo as the National Monument of Bosnia and Herzegovina

4.2. Short Historical Genesis and Development of the Historic Urban Landscape of Sarajevo and Its Main Characteristics

4.3. The Values of the Historic Urban Landscape of Sarajevo and Their Relation to the Measures of Protection Created by the BiH Commission to Preserve National Monuments

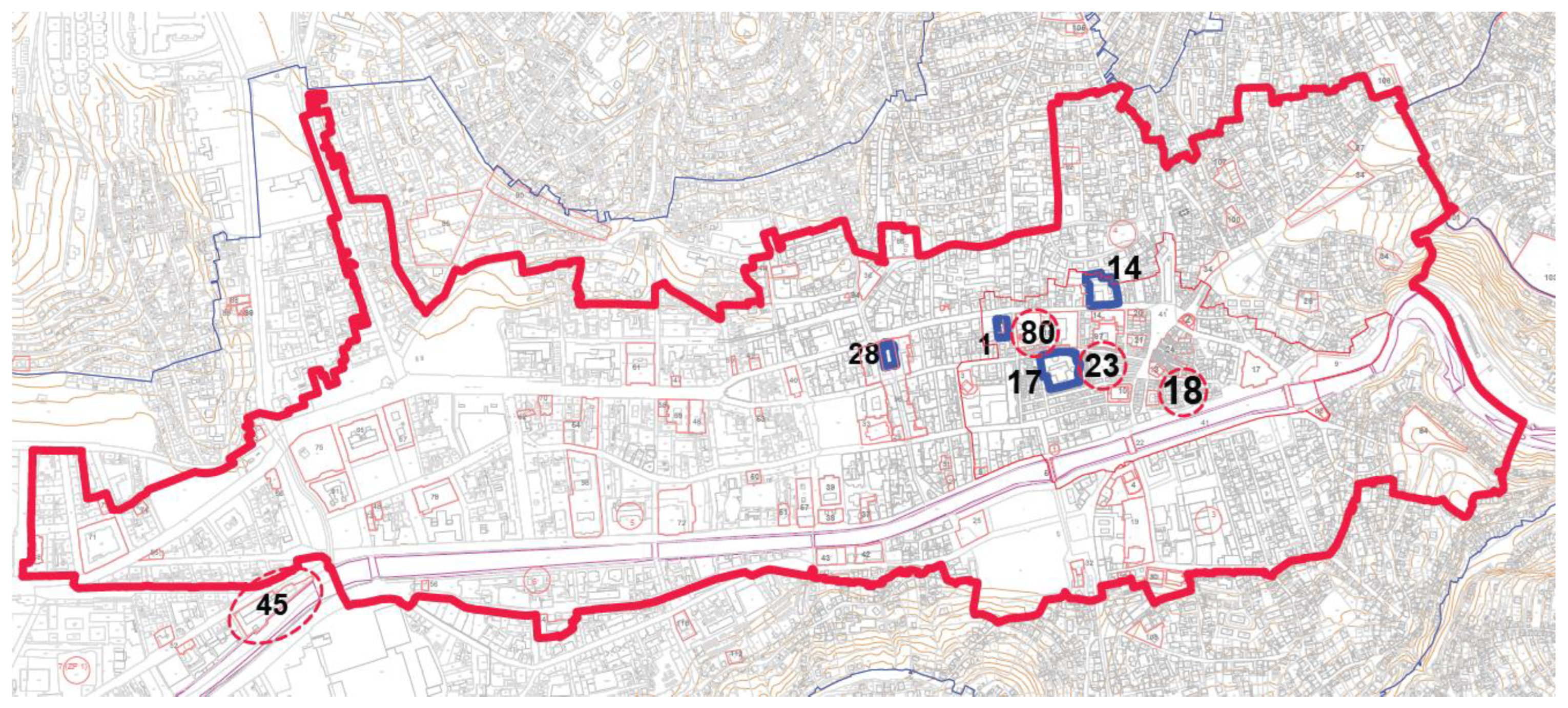

4.4. Case Studies: Contemporary Interventions and Transformation of the Urban Landscape of Sarajevo

4.4.1. Case Studies Regarding the Historical Urban Area of Sarajevo Čaršija Developed during the Ottoman Period

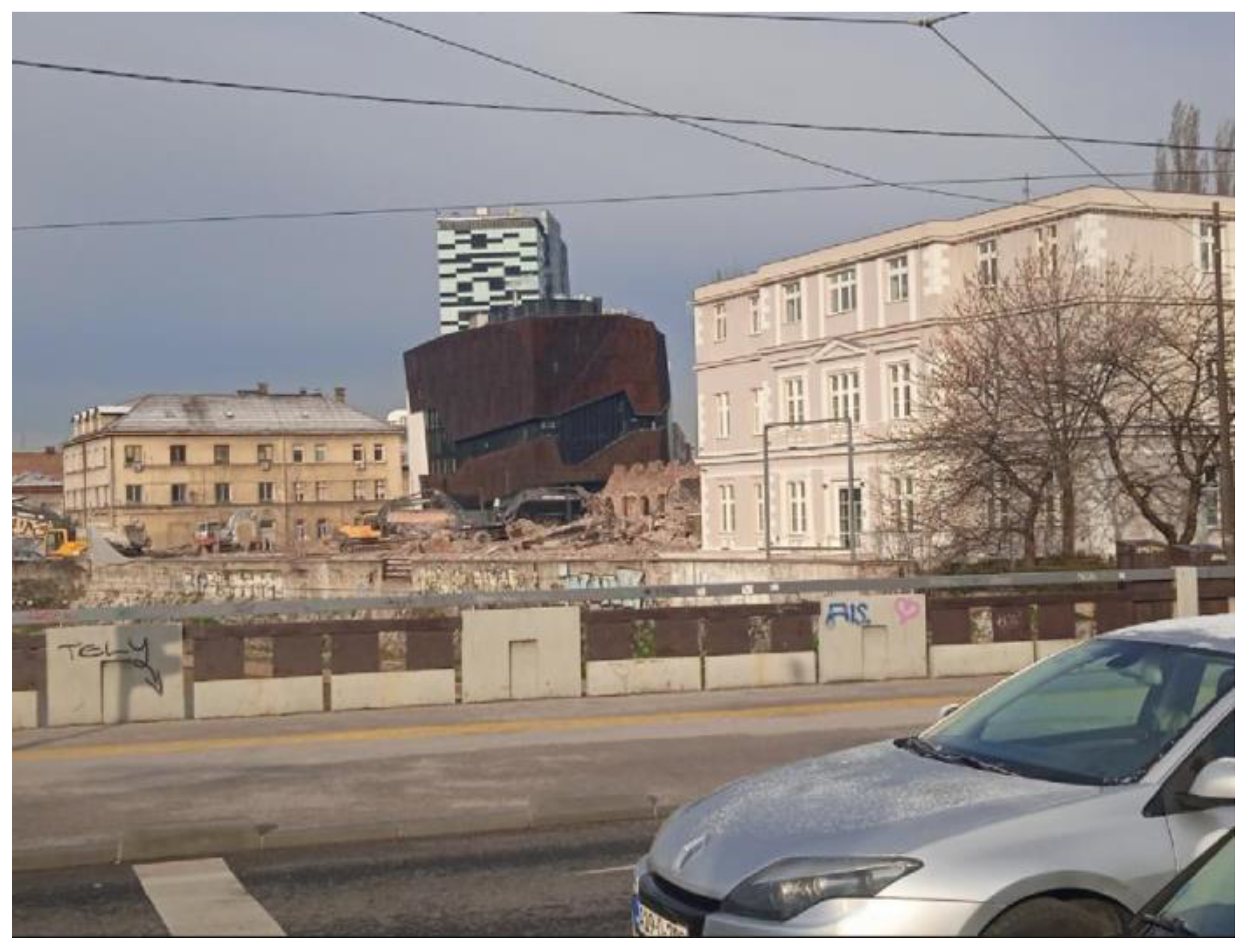

4.4.2. Case Studies Related to the Marijin Dvor Quarter, Which Developed during the Austro-Hungarian Period and Are Part of the Historic Urban Landscape of Sarajevo

- … acknowledging the scarcity of material remains (with only the remains of walls and the absence of industrial plant remnants), modern interventions should aim to highlight the symbolic connotations of the Austro-Hungarian period.

- It is permissible to incorporate modern alternative technologies aimed at environmentally friendly energy production as a form of creative expression… the use of photo-sensitive materials … might be explored. Additionally, harnessing wind and water energy from the Miljacka River is feasible.

- …it is important to maintain the functional and historical continuity of the place.

- It is necessary to create a solution that will not disturb the City’s ambient whole in terms of form and dimensions…

5. Discussion

5.1. Drafting of Spatial-Planning Documents, Actors of Implementation, Decisions Related to the Protection of the Historic Urban Landscape of Sarajevo, and Protection Measures

5.2. Some Dilemmas Related to the Classification of the Urban Landscape of Sarajevo

5.3. Urban Transformation of the Historic Urban Landscape of Sarajevo, Contemporary Interventions, and Protection of Its Architectural Heritage

6. Conclusions

- It is necessary to propose a simplification of the decision-making and implementation system. The Canton of Sarajevo and the associated institutes for planning and heritage protection should be given greater autonomy when planning the creation of spatial plans, allowing for a freer interpretation of certain protection measures. In such complicated administrative systems, the obligation to create combined work teams should be introduced to increase decision-making efficiency and achieve benefits for the historical urban landscape.

- It is crucial to reduce the influence of interest lobbies on institutions that are directly related to the development of contemporary interventions that affect the transformation of the historic urban landscape of Sarajevo.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Notes

| 1 | Although an insufficiently researched area, it can be assumed that such a development is to a certain extent connected with the phenomenon of Neoliberalism, which is defined as: A type of liberalism that favors a global free market, without government regulation, with businesses and industry controlled and run for profit by private owners—Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries, neoliberalism noun-Definition, pictures, pronunciation and usage notes|Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary at OxfordLearnersDictionaries.com. Available online: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/neoliberalism (accessed on 14 September 2023). |

| 2 | Conceptual Solution for the Protection of the Building Complex of the Hiseta Thermal Power Plant and the Interpolation of Modern Structures—Idejno Rješenje Zaštite Graditeljske Cjeline Termocentrale Hiseta i Interpolacije Savremenih Struktura; Sarajevo, November 2016—Letter from the Federal Ministry of Spatial Planning Dated 26.12.2016; Sent to the Commission to Preserve National Monuments of Bosnia and Herzegovina. |

References

- Heckmann-Umhau, P. Ephemeral Heritage: The Ottoman Centre of Austro-Hungarian Sarajevo (1878–1918); Pascariello, M.I., Veropalumbo, A., Eds.; La Città Palinsesto; Tracce, Sguardi e Narrazioni Sulla Complessità dei Contesti Urbani Storici; Volume II: Rappresentazione, Conoscenza, Conservazione; Federico II University Press: Naples, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Onesti, A. Italian ministry of culture. In Il Recupero Edilizio Nell’approccio del Paesaggio Storico Urbano; Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II: Naples, Italy, 2013; Volume 13, p. 157. ISSN 1121-2918. [Google Scholar]

- Bilušić, B.Đ. Landscape as Cultural Heritage. Methods of Recognition, Evaluation and Protection of Croatian Cultural Landscapes—Krajolik Kao Kulturno Naslijeđe. Metode Prepoznavanja, Vrjednovanja i Zaštite Kulturnih Krajolika Hrvatske); Ministry of Culture of Republic of Croatia, Department for the Protection of Cultural Heritage (Uprava za Zaštitu Kulturne Baštine): Zagreb, Croatia, 2015; p. 11.

- Gallozzi, A. Cassino tra Vecchia e Nuova Forma Urbana. Trasformazioni e Permanenze nel Disegno Della Città—VI Convegno Internazionale di Studi. Città Mediterranee in Trasformazione. Identità e Imagine del Paesaggio Urbano tra Settecento e Novecento; Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane; CIRICE—Centro Interdipartimentale di Ricerca sull’Iconografia della città Europea, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II: Naples, Italy, 2014; pp. 1003, 1004, 1009, 1010. [Google Scholar]

- Ćorović, A. Magazine “Confronti” n. 2–3; Quaderni di Restauro: Naples, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ćorović, A. Contemporary Interventions in Historical Nucleus of the City of Sarajevo. Master’s Thesis, Faculty of Architecture in Sarajevo, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Statement of Importance—Commission to Preserve National Monuments of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Decision to Adopt the Sarajevo Čaršija as a National Monument of Bosnia and Herzegovina; Commission to Preserve National Monuments of Bosnia and Herzegovina: Sarajevo, Bosnia and Hercegovina, 2014.

- Spasojević, B. The Architecture of Residential Palaces of the Austro-Hungarian Period in Sarajevo (Arhitektura Stambenih Palata Austrougarskog Perioda u Sarajevu); Svjetlost: Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1988; pp. 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bejtić, A. Streets and Squares of Sarajevo, Topography, Genesis and Toponymy (Ulice i Trgovi Sarajeva, Topografija, Geneza i Toponimija); Muzej Grada Sarajeva: Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1973; pp. 284–285. [Google Scholar]

- Commission to Preserve National Monuments of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Decision to Adopt the Historical Urban Landscape of Sarajevo as a National Monument of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sarajevo, 2 November 2020—Odluka Komisije za Očuvanje Nacionalnih Spomenika BH o Proglašenju Historijskog Urbanog Krajolika Sarajeva Nacionalnim Spomenikom Bosne i Hercegovine na Sjednici Održanoj 2 Novembra 2020; Godine u Sarajevu; Commission to Preserve National Monuments of Bosnia and Herzegovina: Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2020.

- Commission to Preserve National Monuments of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Decision to Adopt the Jajce Barrack in Sarajevo as a National Monument of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sarajevo, 12–18 May 2009—Odluka Komisije za Očuvanje Nacionalnih Spomenika BH o Proglašenju Jajce Kasarne u Sarajeva Nacionalnim Spomenikom Bosne i Hercegovine na Sjednici Održanoj od 12. do 18. maja 2009; Godine u Sarajevu; Commission to Preserve National Monuments of Bosnia and Herzegovina: Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2009.

- Commission to Preserve National Monuments of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Decision to Adopt Site and Remains of the Historic Building of the Firuz-Bey Hammam in Sarajevo in Sarajevo as a National Monument of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sarajevo, 28 March–01 April 2008—Odluka Komisije za Očuvanje Nacionalnih Spomenika o Proglašenju Mjesta i Ostataka Historijske Građevine—Firuz-Begovog Hamama u Sarajevu na Sjednici Održanoj od 28. Marta do 1. Aprila 2008; Godine u Sarajevu; Commission to Preserve National Monuments of Bosnia and Herzegovina: Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2008.

- Commission to Preserve National Monuments of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Decision to Adopt Site and Remains of the Historical Complex Termopower Station with the Administrative Building on Hiseta (Marijin-Dvor) in Sarajevo as a National Monument of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Sarajevo, 03–05 March 2015—Odluka Komisije za Očuvanje Nacionalnih Spomenika o Proglašenju Graditeljske Cjeline—Mjesto i Ostaci Električne Centrale sa Upravnom Zgradom na Hisetima (Marijin-Dvoru) u Sarajevu na Sjednici Održanoj od 3. do 5. Marta 2015. Godine u Sarajevu; Commission to Preserve National Monuments of Bosnia and Herzegovina: Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2015.

- Ćorović, A. Andrea Bruno—Creating a New Authenticity in the Contemporary Approach to Cultural and Historical Heritage (Andrea Bruno—Kreiranje Nove Autentičnosti u Suvremenom Pristupu Kulturno-Povijesnoj Baštini). Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Architecture in Sarajevo, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 27 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mastropiero, M. Beyond Restoration—Architecture between Conservation and Reuse. Projects and Realizations by Andrea Bruno (1960–1995) (Oltre il Restauro—Architetture tra Conservazione e Riuso. Progetti e Realizzazioni di Andrea Bruno (1960–1995); Libra Immagine: Milan, Italy, 1996; p. 60. [Google Scholar]

- Sarajevo—Jerusalem of Europe|WebPublicaPress. Online Magazine, 6 June 2015. Available online: https://webpublicapress.net/pope-francis-calls-sarajevo-jerusalem-of-europe/ (accessed on 7 October 2023).

- Principles and Guidelines for the Preservation of National Monuments, Commission to Preserve National Monuments of BH, Sarajevo April 2019—Principi i Smjernice za Očuvanje Nacionalnih Spomenika; Komisija za Očuvanje Nacionalnih Spomenika BH: Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2019.

- UNESCO. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention; Part IIA Paragraph 47; UNESCO: Landais, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Vienna Memorandum: The “Historic Urban Landscape” Approach; UNESCO: Landais, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Operational Guidelines. In Guidelines on the Inscription of the Specific Types of Properties on the World Heritage List, Annex 3; UNESCO: Landais, France, 2017; pp. 80–87. [Google Scholar]

- Tashlihan: Results of the Survey and Attitude of the AABH–Sarajevo, Association of Architects in Bosnia and Herzegovina, 31 July 2017. Available online: https://aabh.ba/taslihan-rezultati-ankete-i-stav-aabh/ (accessed on 20 April 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Corovic, A.; Obralic, A. Contemporary Transformations of the Historic Urban Landscape of Sarajevo and Social Inclusion as a Traditional Value of a Multicultural Society. Land 2023, 12, 2068. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12112068

Corovic A, Obralic A. Contemporary Transformations of the Historic Urban Landscape of Sarajevo and Social Inclusion as a Traditional Value of a Multicultural Society. Land. 2023; 12(11):2068. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12112068

Chicago/Turabian StyleCorovic, Adi, and Ahmed Obralic. 2023. "Contemporary Transformations of the Historic Urban Landscape of Sarajevo and Social Inclusion as a Traditional Value of a Multicultural Society" Land 12, no. 11: 2068. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12112068

APA StyleCorovic, A., & Obralic, A. (2023). Contemporary Transformations of the Historic Urban Landscape of Sarajevo and Social Inclusion as a Traditional Value of a Multicultural Society. Land, 12(11), 2068. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12112068