4. Result and Discussions

Introduction

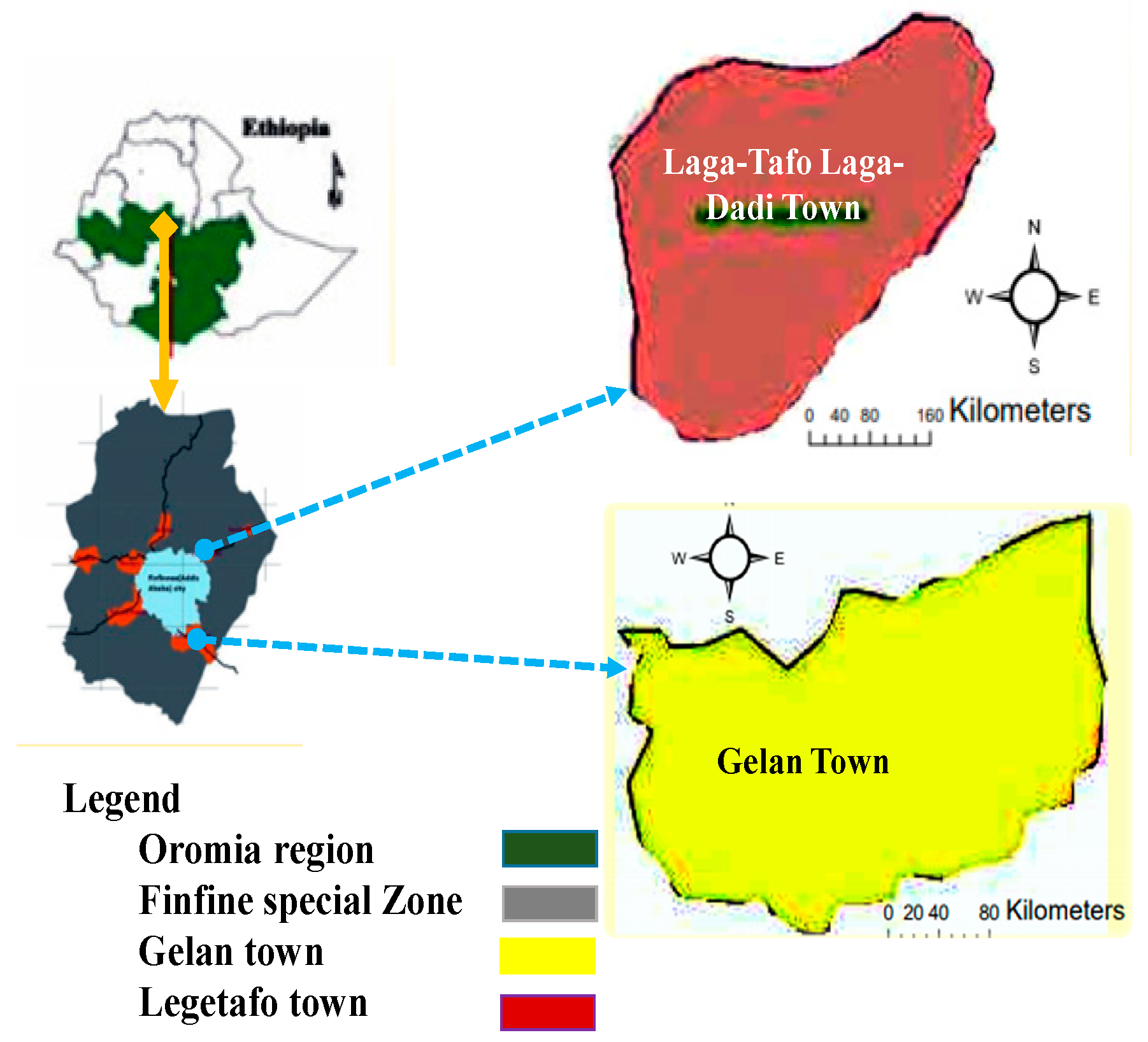

This study focused on the assessment of the socioeconomic effects of good governance practice in urban land management by focusing on the social, economic, and environmental aspects of towns. However, urban land management systems often fail due to weak governance, especially in these study areas. The survey results found in the study areas showed that the practice of good governance in daily activities has failed in terms of urban land management. Urban land management suffers from a lack of transparency and accountability due to the complexity of regulatory frameworks and the complexity of urban land policies. Therefore, the detailed results of the effects of weak governance on urban land management in the study areas are discussed in the following.

Urban Land Management and Social Inclusion

The key informant interviews—particularly those with kebele officials who governed peri-urban areas— revealed that both towns lacked basic infrastructure and services because their residents did not follow land-use plans and did not receive the necessary building permits. As a result, they occasionally did not have access to services and employment prospects. Since their buildings were not registered, they were unable to obtain a kebele identity card. The implications of these studies found that weak governance in urban land management hits the poor particularly hard, as they lack the means to pay bribes to obtain services and cannot afford legal protection, particularly in order to exercise their land rights and defend themselves in land disputes. Residents often have no security on urban land or in the dwellings in which they live. The present study is consistent with the study conducted by [

3,

5]

Urban Land Management and Economic Development

These parts of the survey result focused on the extent to which urban land management promotes efficient land use and land-related economic activities. Moreover, the survey results showed that weak governance and corruption in urban land management constrained development by increasing business risks, reducing incentives to invest, save, and practice entrepreneurship, and distorting incentives in the towns of Lega Tafo, Lega Dadi, and Gelan. Furthermore, in the absence of an efficient urban land registry system, the commercial exploitation of urban land and access to credit were very limited. In towns, there was a system of urban land registration to facilitate land allocation for development purposes, as well as for residential areas. The urban land registry included the sizes, locations, boundaries, and owners of properties, but this was not complete in these towns. Registered transactions took place between private individuals and between private and government entities that were related to land, but not for its sale, as land cannot be sold. The number of respondents using their urban land for commercial purposes was low due to a lack of registration and property security in the study areas. In addition, the interviews with key informants showed that using urban land for agricultural and other investment purposes decreased, even in the peri-urban areas.

As indicated in

Figure 2, the respondents were asked to rate their opinions on efficient urban land management that would entail economic development. A total of 173 (44.2%) and 77 (19.7%) of the respondents chose “disagree” and “strongly disagree”, respectively, while 89 (22.8%) and 22 (5.6%) of the respondents chose “agree” and “strongly agree”, and 30 (7.7%) of the respondents chose “undecided”. Thus, from

Figure 2, it was ascertained that the majority (173 (44.2%)) of the respondents confirmed that urban land management hampers economic development due to weak governance in urban land management.

In addition, during the field observations, the researcher observed that urban landholders began to fence off their land for informal transactions and built shanty houses, as the urban land management practices were inefficient; this made the landowners feel insecure even after their land had been registered because expropriation of the land by the state was possible. Because the urban land cadastral system was virtually unenforceable, landowners and investors were not able to use their land efficiently and productively. In addition, peri-urban economic activities were affected due to the weak governance and insecure service delivery in these areas. Therefore, urban land management practices affected the efficiency of land use and economic activities in the towns of Lega Tafo Lega Dadi and Gelan (

Figure 3).

Urban Land Management and Environmental Protection

According to

Figure 4 below indicates that, Respondents were asked to give their opinions on the extent to which urban land management avoided environmental degradation. A total of 207 (52.9%) and 55 (14.1%) respondents answered that they disagreed and strongly disagreed, while 64 (16.4%) and 25 (6.4%) respondents answered that they agreed and strongly agreed, and 40 (10.2%) answered that they were undecided. Thus, from

Figure 4, it can be seen that the majority (207 (52.9%)) of the respondents confirmed that environmental degradation has occurred in the areas due to inefficient urban land management.

In addition, according to the survey results, there were two main reasons for urban land degradation in the study areas. The first reason was the lack of a concrete land-use plan. The urban planning had not been managed properly according to the statutory planning, and the town administrations had no awareness of the purposes of specific land uses or how to effectively deal with these issues. Investors demanded sites that were inconsistent with the land-use planning and were affected by the approval of the town administration, and many projects failed to persuade local communities to accept and implement them. Gradually, this resulted in governance problems among the residents and the growth of the towns. The other factor was the residents’ awareness of environmental issues. The majority of the residents were only aware of physical environmental issues, such as noise pollution and smoke, while solid waste and groundwater pollution are the elements that destroy natural systems in the long run.

Urban Land Management and Public Income

An interview with a key informant revealed that residents evaded taxes by making informal payments. Land-related property valuations for tax purposes were deliberately underestimated to reduce the tax burden. As indicated in

Figure 5, respondents were asked to rate their opinions of the town’s public revenues. A total of 207 (52.9%) and 62 (15.9%) of the respondents answered “disagree” and “strongly disagree”, while 59 (15.1%) and 27 (6.9%) of the respondents answered “agree” and “strongly agree”, and 36 (9.2%) answered “undecided”. Thus, from

Figure 5, it can be seen that the majority (207 (52.9%)) of the respondents confirmed that weak governance in urban land management reduced public revenue.

This study also analyzed the effect of urban land security on land income. The data showed that peri-urban farmers were not yet registered in the towns of Lega Tafo, Lega Dadi, or Gelan. Therefore, the majority of the suburban residents did not pay property taxes, as their land was unregistered. In addition, informal settlers were not required to pay property taxes because the town administrations believed that paying property taxes was a part of the regularization process, but they had lived in the towns for several years. There were streams of municipal revenues that were collected locally from property taxes. While state taxes were collected by regional branches of the Ethiopian Tax and Customs Administration (ERCA), municipal revenues were collected by the lowest echelons of the local government. Just as in urban areas, all taxes and fees collected at the municipal level ended up at the Bureau of Finance and Economic Development for budgeting and redistribution, alongside state taxes and other revenues, such as outdoor loans. The municipal taxes included property taxes. There were currently no so-called property taxes, although there was a council tax, which was also known as a roof tax or a townhouse tax. There were local sources of income related to property tax, such as rent for houses and rent for land, which made up a tiny part of the towns’ budgets. The implications of these results show that weak governance in urban land management reduces public revenue. This finding is in agreement with the study conducted by [

5], but the incidence of this problem was high in the study areas due to the petty corruption in this sector.

Urban Land Management and Land Tenure Security

The rules and regulations that were reviewed showed that the relationship between people and the land is established through land rights, which are administered by the urban land management. The process of determining urban land rights begins with cadastral surveying and land attribution. The surveying office and the land registry did not perform these tasks. The cadastral office did not yet keep any cadastral or land registers in the study areas. Land transfers were not recorded by the land registry, though this should have been done with the technical support of the surveying office. The results of this research show that rights to ownership, transfer, leasing, mortgage, and efficient use of land were not properly available until urban land was registered. Most respondents from both towns answered that although they owned the land and built houses, they had no legal documents to guarantee their rights to use them. There was a risk of community violence over land and insufficient compensation in cases of forced acquisition of urban land. Abuses in urban land management offices jeopardized property security and increased the risk of land disputes. Timbering, falsification, manipulation of urban land documents, bribery, corruption, and favoritism were some of the problems prevalent in the urban land management, particularly in the town of Lega Tafo Lega Dadi. This increased urban land disputes, which accounted for 55 and 60 percent of court cases in the urban areas of the towns of Gelan and Lega Tafo, respectively. Similarly, the undervaluation of urban land in the urban area increased the risk of not receiving adequate compensation in urban land foreclosure cases or defaults on land transactions. As a result, risks were high in both towns, where the land registers were not secure, land information was not easily accessible, and the valuation of land set by the city was far from the market value. Therefore, the initial registration of urban land is essential for ensuring the security of land ownership. However, the system of urban property information collection and land valuation, as well as the behaviors and skills of workers, affects the rights of urban landowners.

The survey results showed that illegal transfers resulted in legitimate owners losing their rights. Informal transfers and ownership of land were not protected by law, and the protections afforded by common tenure were not all-encompassing for newcomers. Those who were able to use the urban land-use registration systems could strengthen their claims on urban land, even if the land was acquired through land grabs. As indicated in

Table 2, respondents were asked to rate their opinions of urban land security as a result of urban land management. A total of 240 (61.4%) and 49 (12.5%) of the respondents answered “disagree” and “strongly disagree”, while 57 (14.61%) and 22 (5.6%) of the respondents answered “agree” and “strongly agree”, and 23 (5.9%) answered “undecided”. Thus, from

Table 2, it can be seen that the majority (240 (61.4%)) respondents confirmed that weak urban land governance resulted in insecure ownership in urban areas.

In general, these results imply that the urban land management did not provide vested rights by ensuring property rights and reducing associated risks, and this cannot be sustained in the study areas due to the indivisibility of the principles of good governance in urban land management. These findings are in agreement with those of the study conducted by the [

13]. Therefore, digitizing town land registers, establishing integrated information systems, providing employees with moral education, and monitoring and regulating their behavior can reduce misconduct, which town governments need to look out for to minimize risks.

Urban Land Management and Land Disputes

According to the land policy of the FDRE, state tenure remains the dominant influence on land tenure; therefore, the establishment of ethnic federalism has direct implications for urban land management, particularly concerning the rights of indigenous ethnic communities. In addition, common tenure systems have retained some influence on urban land management. The government has not attempted to strengthen customary tenure relations in urban areas as a means of pursuing its political goals. This study examined the overlap and divergence between laws and broader ideas used to justify customs, particularly the urban land rights of indigenous people. A case study of urban land disputes in the towns of Gelan and Lega Tafo Lega Dadi demonstrated that these right-wing ideas related to indigenous people remain most relevant to contemporary urban land debates, and that the communities involved in land disputes draw on these ideas to justify their claims to special resources. Meanwhile, the towns’ responses to conflict have been highly ambiguous, failing to defend indigenous land rights consistently with state ownership and to align with the principles of ethnic federalism. As indicated in

Table 2, respondents were asked to rate their views on how urban land management reduces land disputes in cities. A total of 217 (55.5%) and 55 (14.1%) of the respondents answered “disagree” and “strongly disagree”, while 67 (17.1%) and 21 (5.4%) of the respondents answered “agree” and “strongly agree”, and 31 (7.9%) answered “undecided”. Thus, from

Table 2, it can be noted that the majority (217 (55.5%)) of the respondents confirmed that weak governance in urban land management increases urban land disputes in both study areas.

The focus group discussions with both towns’ targeted experts revealed that the other causes of the urban land disputes in the towns of Lega Tafo Lega Dadi and Gelan described in these studies were unfair compensation for displaced farmers due to public purposes, informal settlements, urban land rights for peri-urban peasants, non-recognition of indigenous land rights, overlapping land rights, border demarcation conflicts, and undefined public purposes. Although this study provides examples of displacement of indigenous people, their cultures and norms were not considered consistent with wider interpretations of ethnic federalism. However, there have been other cases in which the rights of indigenous people have been violated as a result of the state providing other immigrants with priority, most notably where the state promoted extensive urban investment. Disputes over indigenous rights, urban land rights, and the political implications of these issues are broadly similar to those happening in the rest of urban Ethiopia. The implications of this study indicate that the ambiguity surrounding urban land tenure creates significant uncertainty regarding the urban land rights of indigenous communities in urban areas.

Urban Land Management and Access to Credit Markets

The survey results showed that weak governance in urban land management encouraged people to seek a higher loan-to-value ratio for urban land that was offered as collateral than banks would prudently lend or a larger loan than the borrower’s income would justify. Informal payments allowed people to receive unfairly inflated collateral valuations or false income declarations, increasing the vulnerability of the banking system. This research analyzed the effects of weak governance on land value, access to credit, and investment. The valuation of urban land for tax purposes, as determined by the municipal land offices, had not yet begun. That being said, the FDRE constitution does not allow access to credit without building property on land, so access to bank credit is not as widely available, but landowners are not benefiting as much as they could. As indicated in

Figure 6, respondents were asked to rate their opinions on access to mortgage markets. A total of 204 (52.2%) and 68 (17.4%) of the respondents answered “disagree” and “strongly disagree”, while 59 (15.1%) and 22 (5.6%) of the respondents answered “agree” and “strongly agree”, and 38 (9.7%) answered “undecided”. Thus, from

Figure 6, it can be seen that the majority (204 (52.2%)) of the respondents confirmed that land credit markets did not exist due to weak governance in urban land management.

Since Ethiopia’s constitution does not allow access to funding with banned land, some communities that had built property on their lands did not have access to collateral, as there was no land value or cadaster without completing the leases. The results showed that a favorable environment for investment was not being created, as land ownership had become insecure. Therefore, land-related economic activities indicated that investment would not increase, as land registration had not yet started. In summary, since urban land ownership had become insecure, land values were not increasing, access to credit was not encouraged, and investment and income did not increase. In addition, access to institutional credit was not enough to drive investment unless it was properly communicated. As long as the land was not registered, the landowners did not want to make long-term and large investments because they could lose their property at any time. On the other hand, access to credit institutions without investment in land was not allowed according to the FDRE land policies.

Urban Land Management and Land Staff Work Ethic

According to interviews with key whistleblower groups, problems with corruption were commonly found in the urban land administrations of the cities of Lega Tafo, Lega Dadi, and Gelan. These were found to be related to systems for land certification papers, the lack of integrated urban land information systems, and inappropriate urban land valuation, the lack of good governance values among staff, and income from land. The data showed that the municipal property tax was traditionally the main source of revenue for both municipalities. This indicated that land registration revenues increased since land regulation had recently started in some zones. In both towns, there was no rating system, and there was a lack of reliable information about the urban real estate market and of a specialized workforce; the use of inappropriate valuation methods led to undervaluation of properties, which was related to the social behavior of the land staff. Consequently, the revenue collected by the state was less than the actual revenue that it could generate. However, complicated procedures for certifying city lots and high transaction costs kept transactions from being registered, and the undervaluation of lots in the towns also reduced potential revenue. Issues such as bribery, fraud, and misconduct existed in both towns, as revealed by the focus group discussions with certain respondents. This indicated that the urban land management in both towns was not free from problems. However, Lega Tafo Lega Dadi had more problems than Gelan according to these polls. As indicated in

Table 3, respondents were asked to rate their opinions on the effects of urban land management on the social behavior of urban land staff. A total of 225 (57.5%) and 57 (14.6%) of the respondents answered “disagree” and “strongly disagree”, while 53 (13.6%) and 18 (4.6%) of the respondents answered “agree” and “strongly agree”, and 38 (9.7%) of the respondents answered that they had doubts. Thus, from

Table 3, it can be stated that the majority (225 (57.5%)) of the respondents confirmed that there were problems with the social behavior among urban land management employees as a result of weak governance. This implied that there were problems with the social behavior among urban land management employees as a result of weak governance.

Urban Land Management and Land Speculation.

The survey results showed that urban areas—in Ethiopia in general and in the study areas in particular—have been growing very rapidly over the last decade, which has resulted in the need for more land for housing and other non-agricultural activities in suburban and urban areas than ever. This has several transformational implications for transitional areas near the towns, including the engulfing of local communities, the exchange of urban land rights, and the change in use from an agricultural to a built ownership system. The outskirts were also the sites of fighting for land among speculators from different backgrounds. As indicated in

Table 4, respondents were asked to rate their views on how urban land management reduces land speculation in towns. A total of 216 (55.5%) and 48 (12.3%) of the respondents answered “disagree” and “strongly disagree”, while 68 (17.4%) and 19 (4.9%) of the respondents answered “agree” and “strongly agree”, and 40 (12.8%) answered “undecided”. Thus, from

Table 4, it can be seen that the majority (216 (55.5%)) of the respondents confirmed that there was a high level of land speculation in the towns due to weak governance. Therefore, this implies that weak governance in urban land management brought high levels of land speculation into the towns.

Urban Land Management and Prevention of Informal Land Markets

The survey results indicated that in these peri-urban areas at the urban–rural interface, the common and interconnected characteristics of land tenure, management/planning, and governance can complicate the delivery of better conditions. Peripheral areas tend to be areas of rapid change, as they are characterized by diverse land uses and tenure structures with overlapping or fragmented systems of urban land management and governance. This transition caused land markets to expand and land to become increasingly commercialized. As a result, urban land transactions became more common in suburban areas, and there was increasing pressure to subdivide land into smaller lots to increase the supply and financial returns. The areas of urban land and property rights can differ markedly from rural areas, often moving from shared ownership structures in more distant rural areas to more individualized forms of ownership structures in urban areas.

As populations in areas grow and community boundaries expand, peri-urban areas can bring local authorities into contact with areas that have traditional tenure relationships for which local government tools are inadequate. This can manifest itself in increased land-related conflicts and disputes, indiscriminate and unregulated urban land development due to land-use change, illegal land transactions, and the proliferation of informal settlements, all of which contribute to increased land tenure insecurity. This situation was exacerbated by the fact that the physical boundaries of the urban areas often did not coincide with their administrative boundaries, and urban and peri-urban areas often failed with their separate administrative courts in Gelan and Lega Tafo Lega Dadi towns, which had different resources, capacities, and political leanings. This undermined the ability of the urban land management to record tenure rights, conduct land-use planning and enforce its results, and maintain land management through land and property taxes. The multiple land tenure systems made it difficult to overcome these land management weaknesses, as the roles and responsibilities were unclear or subject to competition. This also prevented attempts to plan and provide infrastructure and services that would be conducive to economic growth and poverty reduction, including adequate provision of roads, water and sanitation infrastructure, and housing. As indicated in

Table 5, respondents were asked to rate their views on how urban land management prevented informal land markets in the towns. A total of 199 (50.9%) and 68 (17.4%) of the respondents answered “disagree” and “strongly disagree”, while 76 (19.4%) and 18 (4.6%) of the respondents answered “agree” and “strongly agree”, and 30 (7.7%) answered “undecided”. Thus, from

Table 5, it can be seen that the majority (199 (50.9%)) of the respondents confirmed that the informal land markets increased from time to time as a result of weak governance in the towns.

Furthermore, the rapid pace of change in these peri-urban areas highlighted any underlying issues in urban land tenure arrangements, land management, and governance, such as overlapping mandates, conflicts in land tenure systems, weak land management capacities, and broader issues in the political economy that could stall positive reforms. The implications of these results indicate that weak governance in urban land management resulted in an increase in informal land markets from time to time.

Urban Land Management and Informal Settlements

The interviews conducted with the key informal groups and the FGDs revealed that, as the urban communities settled and grew, housing needs become continuously increased from time to time. The critical question that needs to be addressed is the extent to which towns efficiently manage an urban land-use system, which can have a definite impact on urban growth. The survey results showed that a weak urban land management system accelerated informal settlement in urban areas. The proliferation of the poorly controlled development of human settlement has led to many environmental and health-related problems.

Figure 7 shows that uncontrolled development of settlements caused physical disturbances, inefficient land use, excessive encroachment of the settlements on good agricultural land, environmental degradation, and pollution risks in the study areas. In addition, the lack of space and accessibility made it difficult for the government to deploy social and economic services to these areas. As indicated in

Figure 8, respondents were asked to rate their views on how urban land management reduced informal settlements in cities. A total of 228 (58.3%) and 65 (16.6%) of the respondents answered “disagree” and “strongly disagree”, while 42 (10.7%) and 17 (4.3%) of the respondents answered “agree” and “strongly agree”, and 39 (10%) answered “undecided”. Thus, from

Figure 8, it can be noted that the majority (228 (58.3%)) of the respondents confirmed that poor urban land management caused the growth of informal settlements. These findings imply that the poor urban land management system accelerated informal settlements in towns. The proliferation of the poorly controlled development of human settlements led to many environmental and health-related problems.